Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.5 Texcoco jun./ago. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i5.117

Investigation notes

Varieties and population densities of green beans cultivated under greenhouse and hydroponics

1Departamento de Fitotecnia-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco km 38.5. Chapingo, Estado de México, México. CP. 56230. (fsanchezdelcastillo@yahoo.com.mx;j-magdaleno-v@yahoo.com.mx; guadalupeduranp@yahoo.com.mx).

At the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, a technology package has been developed based on a hydroponic commercial orchard (HCH), in which in the same greenhouse different vegetables can be grown intermittently throughout the year. The objective was to define the best varieties and population densities in order to obtain the highest yield in kidney bean to be cultivated within an HCH. Three varieties of determined growth and 10 indeterminate were evaluated in densities of 15 and 25 plants m-2 of greenhouse in the first, and 10 and 15 plants m-2 in the second. The design was randomized complete blocks in divided plots arrangement with four replicates. Precocity and yield variables were evaluated and variance analysis and means comparisons (Tukey, p= 0.05) were performed. The best determined variety was Palma at a density of 15 plants m-2 (3.09 kg m-2 of fresh pod in a 94 days period from planting to harvest), and the best indeterminate variety was HAB-229 with 10 plants m-2 (3.63 kg m-2, in 110 days).

Keywords: Phaseolus vulgaris L.; green beans; vegetables

En la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, se ha estado desarrollando un paquete tecnológico basado en un huerto comercial hidropónico (HCH), en el cual en un mismo invernadero se pueden cultivar diferentes hortalizas de manera intermitente todo el año. El objetivo fue definir las mejores variedades y densidades de población para lograr el mayor rendimiento en frijol ejotero para ser cultivado dentro de un HCH. Se evaluaron tres variedades de crecimiento determinado y 10 indeterminados en densidades de 15 y 25 plantas m-2 de invernadero en las primeras, y 10 y 15 plantas m-2 en las segundas. El diseño fue bloques completos al azar en arreglo de parcelas dividida con cuatro repeticiones. Se evaluaron variables de precocidad y del rendimiento, y se hizo análisis de varianza y comparaciones de medias (Tukey, p= 0.05). La mejor variedad determinada fue Palma a una densidad de 15 plantas m-2 (3.09 kg m-2 de vaina fresca en un periodo de 94 días de siembra a fin de cosecha), y la mejor variedad indeterminada fue HAB-229 con 10 planta m-2 (3.63 kg m-2, en 110 días).

Palabras clave: Phaseolus vulgaris L.; ejote; hortalizas

Introduction

Protected agriculture in México has grown enormously in recent years. Of the greenhouse producers around 40 000 producers, only 2.5% have more than 1 ha, but they agglutinate more than 50% of the surface with this technology, and their production is oriented to export markets (Ponce, 2015), which shows that the vast majority of greenhouse companies in México belongs to small and medium-sized producers (less than one hectare per producer).

About 70% of the area with protected agriculture is cultivated with tomatoes and 25% more with cucumber and chili peppers. This particularly affects small and medium producers who can hardly access export markets or select national markets, so they resort to supply centers where they are paid a very low price.

The diversification of vegetables in greenhouses is difficult, because although some crops increase their yields, they are not profitable because of the low prices at which they are sold. For example, if the string beans are handled as uni-crop and yields oscillated between 2 and 4 kg m-2 (Delgado et al., 2015), it would not be profitable by selling on supply centers at very low prices.

For this reason, an alternative that has been developed at the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH), is the production under a hydroponic commercial orchard scheme, which is defined as a production system where are grown at the same time, and with the same nutrient solution, various vegetables species, planting and harvesting intermittently to have continuous production throughout the year (Moreno et al., 2014). This allows the producer to plan the productions based on what can be sold in local markets, increasing the income by selling at almost final consumer prices. This system has been successfully validated for different leaf and bulb vegetables (lettuce, spinach, arugula, cilantro, radish, chambray onions, beets, chard, etc) and fruit vegetables (tomato, cucumber, chilli peppers, zucchini, among others), and this paper aims to assess the string beans crop to consider its possible inclusion in the orchard.

Moreno et al. (2014), describe the management of green beans in the hydroponic commercial orchard, but they point out that it is still necessary to define which varieties and population density are the most appropriate for this system. Responses to these questions are the objective of this research.

Metodology

The research was carried out in the Experimental Field of the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, from April to July 2013, under greenhouse and hydroponics conditions.

Ten Green bean varieties of undetermined growth habit were evaluated in independent experiments (HAV-2, HAV-27, HAV-44B, HAV-44N, HAV-62, HAV-65, HAV-68, ROJO CELAYA, EJSI-88 and HAB-229), and three varieties of particular habit (PALMA, STRIKE and OPUS). Indeterminate varieties were established in densities of 10 and 15 plants m-2 useful and determined at 15 to 25 plants m-2 useful. The irrigation was given with a nutrient solution containing the following components and concentrations (mg L-1): N= 200; P= 40; K= 200; Ca= 220; Mg= 40; S= 150; Fe= 2; Mg= 1; B= 0.5; Cu= 0.05; Zn= 0.05.

The plants with indeterminate growth were pruned to the height of three meters. A randomized complete block experimental design was used, with split plot arrangement, with four replications. In the large plot the population densities were placed and in the small plot the varieties; the experimental unit consisted of 1.5 m-2 of culture bed.

Early indicator variables were evaluated: days to emergence (DE), days to anthesis (DA), days at the beginning of harvest (DIC) and days at harvest (DFC); and, yield variables and components: sheath fresh weight in kg m-2 (PFV), number of sheaths per m2 (NV), sheath length (LV) and sheath diameter (DV) in a sample of 10 sheaths taken at random per treatment and repetition for each cut. Seven cuts were made in total. For each variable a variance analysis and Tukey comparisons (p= 0.05) were performed.

Results

Early indicator variables

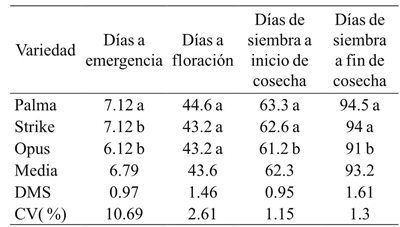

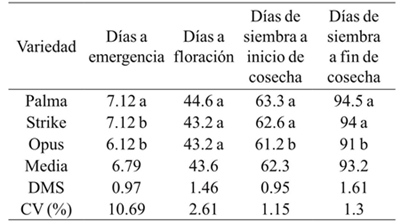

Among the varieties of particular habit, Opus was the earliest with 91 days from planting to harvest (Table 1), similar to those results reported by Salinas et al. (2008); Kenneth (2012).

Table 1 Comparisons of means of indicator variables of precocity in varieties of determined growth in green beans.

Medias con la misma letra en la misma columna, son estadísticamente iguales (Tukey, p= 0.05). DMS: diferencia mínima significativa; CV= coeficiente de variación.

The earliest indeterminate varieties were HAV-44B and HAV-2, both with 99 days to the last cut (Table 2). Salinas et al. (2008) show that in temperate climate under rainfed conditions, the anthesis in HAV-14 variety occurred at 60 days, while under irrigation conditions Peixoto et al. (2002) observed that this event occurred at 42 days. The results indicate that anthesis occurs sooner when there are no water restrictions as in the case of this experiment.

Yield variables and its components

In the varieties of determined habit, Palma was similar to OPUS in yield based on fresh sheath weight (PFV), but superior to Strike (Table 3). There were no differences between varieties (Table 3) in sheath diameter (DV) and pod length (LV), so the higher yield in PALMA was explained by the higher number of harvested sheaths (NV).

Table 3 Comparisons of means of yield variables in determined growing varieties of green bean.

Medias con la misma letra en la misma columna son estadísticamente iguales de acuerdo con la prueba de Tukey (p= 0.05), DMS= diferencia mínima significativa; CV= coeficiente de variación.

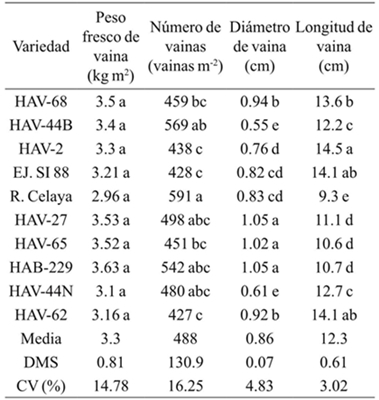

In the undetermined varieties (Table 4), HAV-27 and HAB-229 showed the highest DV (1.05 cm), HAV-2 the highest LV (14.5 cm) and Rojo Celaya the highest NV (591), but regarding fruit yield (PFV) there were no statistical differences. However, the average yield obtained (3.3 kg m-2) in these varieties under the production system used, is superior to that obtained in open field by Esquivel et al. 2006 (2.5 kg m-2) and Salinas et al., 2008 (1.17 kg m-2).

Table 4 Comparisons of means of yield variables in indeterminate growth varieties of green bean.

Medias con la misma letra en la misma columna, son estadísticamente iguales (Tukey, p= 0.05); DMS= diferencia mínima significativa; CV= coeficiente de variación.

The 3.63 kg m-2 of the HAB-229 variety were achieved in 110 days from planting to harvest, so it is posible to obtain a potential annual yield of 11 kg m-2 of greenhouse (110 t ha-1 year-1).

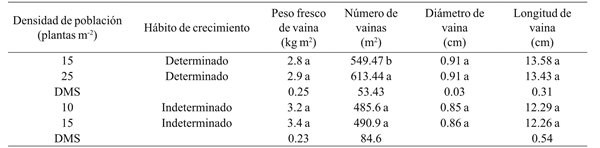

Population density

Regarding population density, in determinate growth varieties, there were only statistically significant differences in favor of higher density (25 plants m-2) in the number of sheaths m-2 (Table 5), without this affecting yield. Morales et al. (2006 and 2008) indicate that with a higher IAF greater interception of the incident solar radiation is achieved for a higher yield. Aguilar et al. (2005) indicate that as the crop cycle advances, the index of leaf area increases, and shading between plants increases, negatively affecting the final yield.

Table 5 Comparison of means of yield variables between two population densities in different green bean varieties.

Medias con la misma letra en la misma columna, son estadísticamente iguales de acuerdo con la prueba de Tukey (p= 0.05); PFV= peso fresco de vaina; NV= número de vainas; DV= diámetro de vaina; LV= longitud de vaina; DMS= diferencia mínima significativa.

In undetermined varieties, there were no differences in yield variables between densities (Table 5). López et al. (2008) also pointed out that green beans in greenhouse in high population densities produce excessive shade, which reduces yield.

Conclusions

The cultivation of Green bean managed as part of a hydroponic commercial orchard represents a viable option for small and medium producers in greenhouse. With the Palma variety which is of determinate growth at 15 plants m-2 the highest yield of sheaths was achieved (3.09 kg m-2 of greenhouse over a period of 94 days from planting to harvest), and the HAB-229 variety which is of indeterminate habit with 10 plants m-2 the yield was 3.63 kg m-2 in a cycle of 110 days.

Literatura citada

Aguilar, G. E. E.; Fucikovsky, Z. T. C. y Mark, E. E. 2005. Área foliar, tasa de asimilación neta, rendimiento y densidad de población en girasol. Terra Latinoam. 23(3):303-310. [ Links ]

Delgado, M. R.; Escalante, E. J. A. S.; Morales, R. E. J.; López, S. J. A. y Rocandio, R. M. 2015. Producción y rentabilidad del frijol ejotero asociado a maíz en función de la densidad y el nitrógeno en clima templado. Uncuyo. 47(2):15-25. [ Links ]

Esquivel, E. G.; Acosta, G. J. A.; Rosales, S. R.; Pérez, H. P.; Hernández, C. M.; Navarrete, M. R. y Muruaga, M. J. S. 2006. Productividad y adaptación de frijol ejotero en el Valle de México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 12(1):119-126. [ Links ]

Kenneth, V. A. R. 2012. Evaluation of six fresh green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties for pod quality and yield. GRAC Crop Research Report No 9: Department of Agriculture, Nassau, Bahamas. 1-8 pp. [ Links ]

López, J. C.; Baille, A.; Bonachela, S. and Pérez, P. J. 2008. Analysis and prediction of greenhouse green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) production in a Mediterranean climate. Bio. Eng. 100(1):86-95. [ Links ]

Morales, R. E. J.; Escalante, E. J. A.; Tijerina, CH. L.; Volke, H. V. y Sosa M. E. 2006. Biomasa, rendimiento, eficiencia en el uso del agua y de la radiación solar del agrosistema girasol-frijol. Terra Latinoam. 24:55-64. [ Links ]

Morales, R. E. J.; Escalante, E. J.A. y López, S. J.A. 2008. Crecimiento, índice de cosecha y rendimiento de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) en unicultivo y asociado con girasol (Helianthus annum L.). Universidad y Ciencia. 24(1):1-10. [ Links ]

Moreno, P. E. del C.; Sánchez, del C. F.; Blancas, C. M. E.; Vásquez, S. A.; González, M. L. y Montalvo, H. D. 2014. Huerto comercial hidropónico: una alternativa de producción de hortalizas en invernadero. Agroproductividad. 7(1):21-27. [ Links ]

Peioxoto, N.; Braz, L. T.; Banzatto, D. A.; Morales, E. A. y Moreira, F. M. 2002. Características agronómicas, productividade, qualidade de vagens e divergencia genética en Feijoo-vegem de crecimiento indeterminado. Hortic. Bras. 20:447-451. [ Links ]

Ponce, P.; Molina, A.; Cepeda, P.; Lugo, E. and MacCleery, B. 2015. Greenhouse control and design. CRC Press. Taylor and Francis Group Boca Raton London UK. ISBN: 9781138026292. 354 p. [ Links ]

Salinas, R. N; Escalante, E. J. A.; Rodríguez, G. M. T. y Sosa, M. E. 2008. Rendimiento y calidad nutrimental de frijol ejotero (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) en diferentes fechas de siembra. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana. 31(003):235-241. [ Links ]

Received: July 2017; Accepted: August 2017

texto en

texto en