Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.3 Texcoco abr./may. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i3.27

Articles

Characterization of the profile of the rural extensión worker in eastern area of Estado de México

1Colegio de Postgraduados. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 36.5. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. CP. 56230. Tel: (595) 9570887. (monsalvo.areli@colpos.mx; jlgcue@colpos.mx; tms@colpos.mx; jequihua@colpos.mx ).

2Campo Experimental Valle de México-INIFAP. Carretera Los Reyes-Texcoco, km 13.5. Coatlinchán, Texcoco, Estado de México, México. CP. 56250. Tel: 01(595) 9212681. (sangerman.dora@inifap.gob.mx).

The research is focused on characterizing the profile of the agricultural extensionist in the eastern area of Estado de México, taking into account the performed functions, problems faced in the productive sector, training needs and competences. The great challenges of the agricultural sector demand to know the profile of the extensionist in order to strengthen their capacities as rural development actors, in charge of transmitting knowledge and technological innovations to the producers to innovate the productive processes. This research uses mixed methodology (qualitative and quantitative), applying a questionnaire to the Extensionists in the Program of Capacity Development, Technological Innovation and Rural Extensionism that serve the Eastern part of Estado de Mexico of the Secretariat of Agricultural Development, Texcoco Regional Delegation. Results obtained, show that the functions carried out by extension workers are technical assistance, technology transfer and training. There are difficulties of a political-institutional nature, but also interest in the permanent updating in different modalities.

Keywords: rural development; rural extension; professional service providers; training

La investigación está enfocado a caracterizar el perfil del extensionista agropecuario del oriente del Estado de México tomando las funciones que desempeña, problemas que enfrenta en el sector productivo, necesidades de capacitación y competencias. Los grandes desafíos del sector agropecuario demandan conocer el perfil del extensionista para fortalecer sus capacidades como actores del desarrollo rural, encargados de transmitir conocimientos e innovaciones tecnológicas a los productores para innovar los procesos productivos. El estudio utiliza metodología mixta (cualitativa y cuantitativa), aplicando un cuestionario a los extensionistas del Programa de Desarrollo de Capacidades, Innovación Tecnológica y Extensionismo Rural que atienden la zona oriente del Estado de México de la Secretaría de Desarrollo Agropecuario, Delegación Regional Texcoco. Los resultados muestran las funciones realizadas por los extensionistas, asistencia técnica, transferencia de tecnología y capacitación. Se observan dificultades de carácter político-institucional, interés en la actualización permanente en diferentes modalidades.

Palabras clave: desarrollo rural; extensión rural; capacitación; prestadores de servicios profesionales

Introduction

The rural environment has great challenges for achieving the development of a sustainable future, poverty is still concentrated among small farmers, day laborers and landless families. Strategies are needed to improve the life quality of rural communities by providing them with infrastructure and services; as well as encouraging the creation of self-employment and lifelong learning programs; seeking economic diversification without endangering resources for future generations; that is, considering “education for rural development” (Paniagua, 2012).

Education and training are powerful tools for combating rural poverty and driving the struggle for inequalities in favor of rural development. Training represents an instrument that contributes to promoting rural development through the active participation of the person or group trained (Jiménez, 2004). In the rural sector, a significant element for training and innovation are actions that have traditionally been called “extensionism”. An important role played by rural extension, promoting agriculture as an engine of economic growth for thousands of families, focused on improving their food security, economic and social management; their livelihoods, in general (RELASER, 2013).

The term “extension” begins to be used to describe adult education programs created by universities, aimed at disseminating knowledge generated to an audience outside the boundaries of the university. It is then adopted in the United States of America by “land grants” established for the teaching of agriculture for the purpose of disseminating programs and agricultural knowledge among farmers (Swanson, 2010).

Over time, extension has been interpreted in different ways: technology transfer, technical assistance or advisory services; whatever the methodology used, it was characterized by a linear approach of extension, limiting the priority attention to the farm and the farmer as a passive participant. Thus, it led to the diffusion of technology and knowledge without considering the individual situation of farmers and isolation of market forces, it led to increases in production but did not always translate into higher income. This orientation has been the most used one by traditional extension systems, including Mexico until 1980, implemented by professionals whose knowledge was limited to the transfer and dissemination of technology (IICA, 2012).

The extension or rural advisory systems is a process of work and accompaniment with the producer (González et al., 2015), it refers to different activities undertaken to provide information and services that farmers and other actors in the innovation system demand to help them developing technical, organizational and management capacities with the purpose of improving their life quality and well-being (GFRAS, 2010). Hence, the main idea is its importance as a tool to promote agricultural development through the dissemination of technology in rural areas (Jiménez, 2004).

In a globalized world agriculture must be competitive in domestic and foreign markets, the contribution of a modern extension service covers a wide range of activities, from production to consumption. Where extension agents should work as “knowledge brokers” to facilitate teaching and learning processes (Aguirre, 2012). However, working to bring changes in the most vulnerable productive systems must contribute to opening up opportunities, improving food security, reducing restrictions on the financial system, helping to mitigate their environmental vulnerabilities, increasing their representativeness in the political and social spheres (RELASER, 2013).

In Mexico, rural learning is known as Extensionism, defined as it seeks to “Extend” (propagate or diffuse) knowledge through actions to promote new technologies and training the producers to improve their productive performance. Technical assistance, technology transfer and training are traditionally considered to be the cornerstones of an extension service (Muñoz and Santoyo, 2010). Its origins arise at the beginning of the XX century, applying actions in the agricultural sector from 1960 to 1990, the Mexican government developed a system of extension and transfer of agricultural technology. In the last twenty years, several changes and institutional innovations were presented and led to its dissolution. On the other hand, the means to stimulate the creation of a private extension market in the Mexican Republic, which supports the execution of governmental programs at local level, started. Nowadays, there is no defined service of agricultural extension, in the rural area the technical assistance is privatized and that originates providers of professional services, those known as providers of professional services (PSP), they bring technical assistance to the producers through advisory and capacity building programs, mediated by the Mexican government through government institutions (OCDE, 2011).

Agricultural policy and its implementation based on the Sustainable Rural Development Act (LDRS) since 2001, supported the generation and diversification of employment, guaranteed the incorporation and participation of the small-scale agricultural sector in national development, marginalized and economically weak sectors of the rural economy. In the area of research and extension, the Law delegated its application to SAGARPA, which coordinates the various bodies of crop trials, agricultural research, technology generation, experimentation and extension. Therefore, it modifies its lines of public policy, proposing new strategies and programs: 1) support to equipment and infrastructure investment; 2) support for agricultural income PROCAMPO; 3) prevention and risk management; 4) capacity building, technological innovation and rural extension; 5) sustainability of natural resources; and 6) transversal projects (Aguirre, 2012).

This vision, considers reducing the dispersion of resources, proposes a greater concurrence, efficiency of programs; as well as undertake territorial projects. Rural development becomes a cross-secretariat-wide program, promotes knowledge-based development. New coordination bodies are designed to link all stakeholders, knowledge networks and technical assistance, training and extension services. For that reason, a “national commission of capacity development, technological innovation and rural extension” and state commissions are established where their governments coordinate and supervise the program, derived from the Law, articles 42 and 48: establishes a system and service of training and comprehensive rural technical assistance (LDRS, 2012).

A new Agricultural Extension System is created with actions and public policies aimed at improving the living conditions of inhabitants in the field of training as an enhancer of economic development, raising the need to contribute with actions and strategies that favor Rural Development (LDRS, 2012). In compliance with these actions, SAGARPA develops the Sectorial Program for Agricultural, Fisheries and Food Development subject to the norms contained in the National Development Plan (2013-2018), emphasizes technical assistance or new extension as an integral strategy to raise productivity and reach the maximum potential of the agri-food sector. To this end, it proposes to apply the practice of knowledge, research and technological development, supported by the link between higher education institutions and research centers with the private and public sectors (SAGARPA, 2013).

The agricultural sector facing great challenges, demands to know the needs and problems faced by the extensionist to strengthen their capacities as rural development actors, in charge of transmitting knowledge and technological innovations to producers that allows them to innovate the productive processes (Landini, 2013a). It is important that the extension worker has the necessary experience and develops skills that will help him / her to face labor, economic and social difficulties that arise in his or her professional work towards the achievement of objectives (Figueroa et al., 2010). The extensionist profile, defined as a set of capacities and competencies that identify their training to face functions and tasks of their work, allowing to assume the responsibilities that are presented (Mayoral et al., 2009).

Méndez (2006) and Cano (2004) mention that the profile of the extension worker must have basic skills such as learning to learn, communicating, coexisting, decision making, expanding their capacities to manage and solve problems and meet individual and social needs. These contents, based on principles and values of ethics, self-esteem, self-control, responsibility, honesty, sociability, respect, tolerance and ability to coexist. Russo (2009), suggests basic reading, writing and cognitive reasoning skills and should develop skills that integrate the use of information and communication technology (TIC).

SAGARPA, proposes a new profile of the extensionist whose objective is to provide quality integral attention to producers in areas of high marginalization through seeking their improvement, seeking to develop capacities, skills, knowledge and adoption of an innovative vision of the value chain that allows them to move from the traditional system to holistic extension. Focused to offer everything that contributes elements in the solution to specific problems of the agricultural, livestock and fishing sector that results in a greater increase and democratization of agri-food productivity (SAGARPA, 2013).

Landini (2013b) emphasizes the importance of extension that has made it possible to reconstruct the profile of rural extension workers working in the Argentine public extension system and contribute elements to the profile of rural extensionists; in addition, analyzes the training needs of rural Paraguayan professionals inquiring about their role, problems they face in their practice and training interests. Based on these studies, Mayoral et al. (2015) present their research with the objective of analyzing the profile of extension workers in Baja California Sur, B. C., Mexico, describing their role as part of their responsibility in the current conditions of the agricultural sector.

In this context, several questions arise: what characteristics does the agricultural extensionist of the eastern area of Estado de Mexico have? what are the functions of the agricultural extensionist?, what are the problems that are faced in the productive sector? and what are their training needs? For these reasons, the objective of this research is to characterize the profile of the agricultural extension worker in the eastern part of Estado de Mexico, taking into account the functions they perform, problems they face, training needs and competencies. The assumption of the research is: the agricultural extensionist of the eastern area of Estado de Mexico is characterized according to parameters such as their functions, problems, competencies and training needs

Materials and methods

The research was carried out in the Eastern region of Estado de Mexico, municipalities of Atenco, Chiautla, Chiconcuac, Papalotla, Tepetlaoxtoc, Texcoco and Tezoyuca; is part of the conurbation zone of the center of the Mexican Republic, has strong concentrations of population in irregular settlements of high agricultural productivity. These municipalities belong to Region XI Texcoco, bordering to the north Region V Ecatepec, south Region III Chimalhuacán, west Ecatepec and Netzahualcóyotl, to the east the states of Tlaxcala and Puebla; they are part of the Metropolitan Zone of the Valley of Mexico (COPLADEM, 2012). Its population, registers 407 694 inhabitants in an area of 727.3 km2, represents 2.69% of the State. Municipalities with the largest surface area are Texcoco (418.7 km2), Tepetlaoxtoc (172.4 km2) and Atenco (94.7 km2), comprising 81.3% of total regional area, the remaining territory (18.7%) occupied by Chiautla (20.1 km2), Tezoyuca (10.9 km2), Chiconcuac (6.9 km2) and Papalotla (3.6 km2) (INEGI, 2010).

The research is a mixed, non-experimental descriptive-explanatory case study (Hernández et al., 2010), the population is the total of agricultural extensionists (17 PSP) attached to the Program of Capacity Development, Technological Innovation and Rural Extensionism Of SAGARPA, coordinated by SEDAGRO, Texcoco Regional Delegation, Estado de Mexico. A questionnaire was designed and applied to obtain information, it consists of five sections: 1) sociodemographic data; 2) functions performed by the extension worker; 3) problems faced in the productive sector; 4) training needs; and 5) self-assessment of competencies.

The questionnaire went under tests: expert review, pilot, content validity and reliability Cronbach alpha, instrument analysis giving a value of 0.895 a maximum of 1, considered reliable. It was applied in SEDAGRO field and facilities (October 22, 2015 to February 4, 2016). Data were analyzed with descriptive statistics and frequencies with SPSS software v.21.0, qualitative: participant observation in the field and work meetings in the office of Rural Development- SEDAGRO; and discourse analysis with open-ended questions Hernández et al. (2010).

Results and discussion

From the information obtained from the survey: 64.7% are men and 35.3% correspond to women who emphasize their labor participation. Reported ages are 26 to 60 years with an average of 36 years of age. These data, in agreement with the results obtained by Mayoral (2015), mention that it is the range of productive ages to develop the extension activity.

The extensionists interviewed report different categories of work: 41.2% are enrolled in the national extension program, 41.1% are accredited by their experience, and the rest (17.6%) are certified by another institution. The information reported, agrees with their work experience that goes from one to 15 years; 17.6% of them have at least one year of experience, two years (5.9%), three (29.4%) and four (11.8%); one person (17.7%) from eight to 10, another (17.7%) have 12 to 15 years of work. The experience allows them to have a deeper knowledge of the producers and their environment in order to provide the extension service.

In terms of academic training, they have a bachelorʼs degree (70.6%) and postgraduate (29.4%), having completed their last level of studies in institutions that offer agricultural programs such as Chapingo Autonomous University (52.9%), Postgraduate College Autonomous State of Mexico (11.8%), Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (5.9%) and the Technological Institute of Sonora (5.9%). Its areas of expertise include agriculture (35.3%), livestock (35.3%), food (5.9%), education (5.9%), other areas including agribusiness, biotechnology and botany (17.6%). This academic profile is congruent with the activities carried out in the extension service.

The extensionists interviewed are full-time state employees, whose work spans seven municipalities (Atenco, Chiautla, Chiconcuac, Papalotla, Tepetlaoxtoc, Texcoco and Tezoyuca), commenting that they also collaborate in others: Los Reyes la Paz, Chicoloapan and Chimalhuacán. Their place of residence is Texcoco (76.5%), Tepetlaoxtoc (5.9%), Chiautla (5.9%) and Ixtapaluca.

In the agricultural cycle 2015-2016, extension agents provided agricultural and livestock services to 510 producers in the eastern region in five production chains: bovine milk (120 producers), sheep (60 producers), maguey (60 producers), vegetables (180 producers) and wheat (90 producers). In carrying out their technical assistance activities, they encounter a number of problems that reduce the impact of their actions (Landini, 2007).

More often, their activities are related to the formation of producer groups, transfer of technology, technical assistance and work with social groups (women, children and the elderly). Also they design productive projects, identify population demands, produce material to train and promote the producers self-management. These actions coincide with Aguirre (2012); however, despite the time and transformations of the Mexican extension system, the promotion and transfer of new technologies, technical assistance, advisory services and training producers with the purpose of improving their productive performance, remain as main axes.

According to the testimony of the extensionists, there is not always continuity in the projects and programs: “the extensionist’s work must be supported and given continuity, and the progress made with the producer is truncated since there is no follow-up”, “the extension and the participation of the producers must be strengthened”, in addition there is a gap of the extensionist when starting the service and the stage of cultivation, contracting should be at the beginning of the year nd “support is needed for the acquisition of technologies”. Also, there is a big problem to market and link with the market, mainly for small producers, they point out “Production costs are very high and there are no marketing channels ” (Interviews, February 2016).

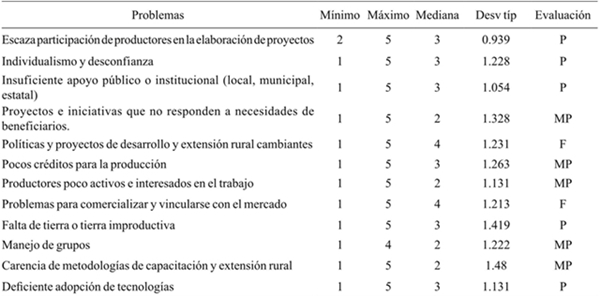

Table 1 Frequency analysis of extensionist problems.

Evaluación de acuerdo a la mediana. Donde: 1= nunca (N); 2= poco (P); 3= muy poco (MP), 4= frecuentemente (F); 5= siempre (S).

From the perspective of the extensionist according to the list of difficulties, it is observed that they are of a political - institutional nature. Landini (2013a) precise, lack of rural development policies has been a recurrent problem not only in Mexico but in Latin America. The OCDE (2011), when analyzing institutional reforms, concludes that bureaucratic structures have been proved to be inflexible and do not respond to a changing sector, the organization level of farmers remains low, this issue must be taken into account in the policies designing.

Training has been a key issue at the institutional level: 94.1% of respondents are updated or trained by government institutions such as SAGARPA (41.2%), INCA RURAL (82.4%), FIRA (11.8%), ICAMEX (23.5%), INIFAP (29.4%), College of Postgraduates (29.4%) and Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (58.8%). The frequency of training is annual (58.8%), every three months (23.5%) and when there is opportunity (17.6%). This training is financed by them and the company where they work (47.1%), comes from the government (29.4%), themselves (17.6%) and is financed by the company where they work (5.9%). Extensionists are interested in receiving more courses and show preference in face-to-face courses (100%), with TIC support being semi-attended (88%) and online (53%).

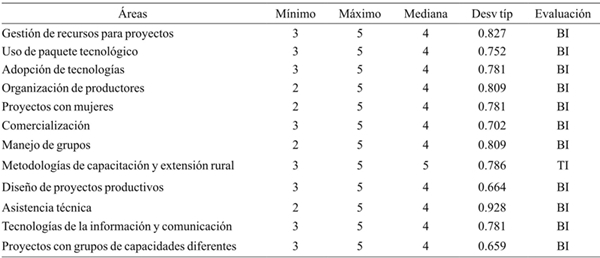

Through government institutions actions have been established to train, an instrument of national public policy to promote rural development and meet the challenges of the agricultural sector (LDRS, 2012). In Table 2, several areas of interest to receive training, greater interest (88.4%) reported in training methodologies and rural extension, theses coincides with the work of Landini (2013c). In addition, they emphasize organization of producers, commercialization, group management, design of productive projects (88.2%). In adopting technologies, projects with women, TIC use, resource management and technical assistance (70.6%), projects with people of different capacities (76.5%), last use of technology packages (58.8%).

Table 2 Areas of interest for training.

Evaluación de acuerdo a la mediana. Donde: 1= ningún interés (NI); 2= bastante desinteresado (BD); 3= algo interesado (AI); 4= bastante interesado (BI); 5=totalmente interesado (TI).

Mexico promotes an integral extension, permanent access to training and certification processes to develop capacities that favor the processes of rural development (SAGARPA, 2015). In this regard Paniagua (2012), requires strategies to improve the quality of life of rural communities, providing them with infrastructure and services of the extensionist. Regarding to self-evaluation of extensionistʼs abilities, they evaluated themselves with higher scores in the values and ethics category, they are conceived as people with solid principles and values. They consider that they have a profile, learning to learn skills, creative and innovative thinking, decision making, problem solving, among others. Those are skills that coincide with the proposals of Cano (2004), Méndez (2006) and GFRAS (2010).

Table 3 Analysis of capacities of the extension worker.

SAGARPA (2015); Méndez (2006); Cano (2004). Evaluación de acuerdo a la mediana. Donde: 1= no tengo habilidad (NH); 2= muy poca habilidad (MPH); 3= poca habilidad (PH); 4= hábil (H); 5= muy hábil (MH).

Conclusions

The academic profile of the extensionist stands out; (Natural resources, plant protection, plant physiology, botany, biotechnology); training in agriculture, livestock and food (agronomists specializing in animal husbandry, plant engineering, agro-industries and veterinary); there are no professionals in social sciences. Most of them with higher education: Chapingo Autonomous University and Postgraduate College.

Functions they perform: training of producer groups, transfer of technology, technical training in multiple areas, work with social groups, draw up plans, design productive projects, identify demands of the population, produce materials to train producers and promote self-management. They require training in methodologies and use of TIC.

Strengthening the extensionism and participation of producers requires reforms to public policies.

The competencies of the extension worker comply with the scheme proposed by SAGARPA. Their holistic vision is still pending.

Literatura citada

Aguirre, F. 2012. El nuevo impulso de la extensión rural en América Latina. Situación actual y perspectivas, disponible en: http://www.redinnovagro.in/documentosinnov/nuevoimpulso.pdf. [ Links ]

Cano, J. 2004. Globalización, pobreza y deterioro ambiental. El perfil del extensionista a la urgencia de los tiempos. Ediciones INTA.Revista Dialoguemos. 8(14):5-10. [ Links ]

COPLADEM (Comité de Planeación para el Desarrollo del Estado de México) . 2012. Plan de Desarrollo 2011-2017. Toluca, México. [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2012. Ley de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable. México. [ Links ]

Figueroa-Rodríguez, B.; Figueroa-Rodríguez, K.; De los Rios-Carmenado,I. y Hernández-Rosas, F. 2010. La empresarialidad en prestadores de servicios profesionales agropecuarios. Campeche, México.Ra Ximhai, Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México Mochicahui. El Fuerte, Sinaloa. 355-364 pp. [ Links ]

Geilfus, F. 2002. 80 herramientas para el desarrollo participativo. Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA).Costa Rica. http://www.iica.int. [ Links ]

Landini, F. 2013c. Necesidades formativas de los extensionistas rurales paraguayos desde la perspectiva de su función, sus problemas y sus intereses. Trabajo y Sociedad. 20:149-160. [ Links ]

GFRAS. 2010. Marco estratégico a largo plazo (2011-2016). Echenique J. 2004. La institucionalidad del sistema de generación e innovación tecnológica agropecuaria. FAO, Santiago, Chile. [ Links ]

González-Tena P. A. ; Rendón-Mendel R.; Sangerman-Jarquín D.; Cruz-Castillo J. G. y Diaz J. J. 2015. Extensionismo agrícola en el uso de tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TIC) en Chiapas y Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cien. Agríc. 6(1):175-186. [ Links ]

Hernández, R.; Fernandez, C. y Baptista, P. 2010. Metodología de laInvestigación. 5ta ed. McGraw-Hill Interamericana. 613p. [ Links ]

IICA, INCA Rural. 2012. Extensionismo y gestión territorial para el desarrollo rural. IICA- México. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2014. http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/temas/default.aspx?s=est&c=17484. [ Links ]

Jiménez, M. A. 2004. Education and Rural Development in México. PH.D. in Education. Newport University. [ Links ]

Landini, F. 2013a. Problemas enfrentados por los extensionistas rurales argentinos en el ejercicio de su labor desde su propia perspectiva. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural.51(1):s079-s100. [ Links ]

Landini, F. 2013b. Perfil de los extensionistas rurales argentinos del sistema público. Mundo Agrario. 27 p. [ Links ]

LDRS (Ley de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable). 2012. Diario Oficial de la Federación. México. [ Links ]

Mayoral-García, M.B.; Cruz-Chavez, P. R.; Duarte-Osuna, J. D. y Juárez-Mancilla, J. 2015. El Perfil del extensionista rural en Baja California Sur (Bcs), México. Revista Global de Negocios. 3(3):43-54. Available at SSRN: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2658324. [ Links ]

Méndez, M. J. 2006. Los retos de la extensión ante una nueva y cambiante noción de lo rural. Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias-Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Medellín, Colombia. [ Links ]

Muñoz-Rodríguez, M. y Santoyo-Cortés, V. H. 2010. Del extensionismo a las redes de innovación. In: del extensionismo agrícola a las redes de innovación rural. Aguilar-Ávila, J.; Altamirano-Cárdenas, R. J. y Rendón-Medel, R.(coordinadores). UACH-CIESTAAM.Chapingo Estado de México. 31-70 pp. [ Links ]

OCDE (Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico).2011. Análisis del extensionismo agrícola en México. OCDE París. [ Links ]

Paniagua, J. 2012. Proyecto de educación social para el desarrollo local en el medio rural: animación sociocultural y emprendimiento.Universidad de Valladolid. Escuela Universitaria de Educación Palencia. [ Links ]

Russo, R. 2009. Capacidades y competencias del extensionista agropecuario y forestal en la globalización. Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica. Comunicación. 18(2):86-91. [ Links ]

SAGARPA. 2013. Programa sectorial de desarrollo agropecuario,pesquero y alimentario. 2013-2018. México. [ Links ]

Swanson, B. E. y Rajalahti, R. 2010. Strengthening agricultural extensión and advisory systems: procedures for assessing, transforming,and evaluating extension systems, world bank, agriculture and rural development, discussion paper 45, Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República (2013). Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2013-2018. México. [ Links ]

RELASER (Red Latinoamericana para Servicios de Extensión Rural).2013. Extensión rural con enfoque para la inclusión y el desarrollo rural. Revista Claridades Agropecuarias. 42-48 pp. [ Links ]

Received: January 2017; Accepted: April 2017

texto en

texto en