Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.2 Texcoco Fev./Mar. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i2.57

Articles

Foliar iron and plastic mulch in Capsicum chinense Jacq. infected with tospoviruses

1Instituto de Ciencias Agrícolas-Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (ICA-UABC). Carretera a Delta, s/n. Ejido Nuevo León, Mexicali, Baja California, México. CP. 21705. (torres.ariana@uabc. edu.mx, lourdescervantes@uabc.edu.mx).

2Campo Experimental Valle de Mexicali-INIFAP. Carretera a San Felipe, km 7.5. Colorado Dos, Mexicali, Baja California, México. (morales.antonio@inifap.g ob.mx).

3Sitio Experimental Caborca-INIFAP. Avenida S, No. 8 norte. H. Caborca, Sonora, México.CP. 83600. (grijalva.raul@inifap.gob.mx).

Of the diseases that affect mainly the habanero pepper are those caused by tospoviruses, which can completely reduce its yield. During the year 2013, an experiment was carried out with two varieties of habanero pepper (one infected and one not infected with tospoviruses), with the objective of evaluating the application of iron in foliar form and the plastic padding on the performance, index SPAD and NO3 - in the petiole cell extract (ECP). The treatments were distributed under a factorial design 2*2*4 (two varieties, one infected with tospoviruses and another healthy, with or without application of foliar iron, and four colors of plastic mulch). The results showed that the infection of the variety and the application of foliar iron did not affect yield (p˃ 0.05); however, the color of plastic mulch is significantly modified (p< 0.05), increasing when using transparent and silver mulch. The SPAD index in the leaves was significantly affected (p< 0.05) at the beginning of the experiment by treatments varieties and application of foliar iron, whereas at 90 days after the transplant was affected by the quilting, varieties and application of iron (p< 0.005), as well as the interaction between padding and iron application (p< 0.02). On the other hand, NO3 - concentrations in ECP were affected most of the time in the experiment. The highest concentrations of NO3 - were present in plants developed in plastic mulch and in those that did not receive application of foliar iron.

Keywords: chlorophyll; diseases; habanero; nitrates

De las enfermedades que afectan mayormente al chile habanero se encuentran las provocadas por tospovirus, los cuales pueden reducir completamente su rendimiento. Durante el año 2013, se realizó un experimento con dos variedades de chile habanero (una infectada y otra no infectada con tospovirus), con el objetivo de evaluar la aplicación de hierro en forma foliar y el acolchado plástico sobre el rendimiento, índice SPAD y NO3 - en el extracto celular del peciolo (ECP). Los tratamientos se distribuyeron bajo un diseño factorial 2* 2*4 (dos variedades, una infectada con tospovirus y otra sana; con o sin aplicación de hierro foliar, y cuatro colores de acolchado plástico). Los resultados obtenidos mostraron que la infección de la variedad y la aplicación de hierro foliar no afectaron el rendimiento (p˃ 0.05); sin embargo, el color de acolchado plástico si lo modificó significativamente (p< 0.05), incrementándose al utilizar el acolchado trasparente y plateado. El índice SPAD en las hojas fue afectado significativamente (p< 0.05) al inicio del experimento por los tratamientos variedades y aplicación de hierro foliar, mientras que a los 90 días después del trasplante fue afectado por el acolchado, las variedades y la aplicación de hierro (p< 0.005), igual que la interacción entre el acolchado y la aplicación de hierro (p< 0.02). Por otro lado, las concentraciones de NO3 - en el ECP resultaron afectadas durante la mayor parte del tiempo en el experimento. Las mayores concentraciones de NO3 - se presentaron en las plantas desarrolladas en acolchado plástico y en las que no recibieron aplicación de hierro foliar.

Palabras clave: clorofila; chile habanero; enfermedades; nitratos

Introduction

The production area of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) in Mexico is around 965 hectares, with average yields of 5.4 t ha-1 (SIAP, 2013). Yucatan is the leading state in production surface with about 708 ha and yields of 75 t ha-1. The following states in production are Tabasco, Campeche and Quintana Roo with 143, 51 and 36 ha respectively. The average yield obtained is between 10 and 40 t ha-1, (Macías-Rodríguez et al., 2013). The production of habanero pepper is attractive because the fruit can be harvested ripe in green or orange color and it is consumed as fresh product or processed as a sauce, in addition that can reach prices of up to $30.00 pesos or 2.00 US dollars per kilogram, both in the national market and in the international market respectively (Macías-Rodríguez et al., 2013).

Of the numerous diseases associated with the cultivation of the habanero pepper are those of viral origin, mainly the virus of the iris (IYSV) and the tanning virus of the tomato (TSWV) belonging to the tospoviruses genus (Margaria et al., 2014; Fanigliulo et al., 2014; Baq et al., 2015), whose infective nature represents one of the threats of major importance for this crop because it reaches losses of up to 100% (Pennazio et al., 1996; Roggero et al., 2003; Pérez et al., 2004). This reduction in yield is generally related to the early presence and severity of foliage symptoms (Moriones et al., 1998), particularly the loss of chlorophyll in the leaves (Cabrera et al., 2009). This loss of chlorophyll appears as an indicator of biotic stress in the plant (Carter and Knapp, 2001; Gill and Tuteja, 2010).

The type of nutrition of plants infected by viruses has been shown to have a marked effect on the expression of symptoms produced by these pathogens (Amtmann et al., 2008; Dordas, 2008; Huber and Jones, 2013). In the specific case of the TSWV, a certain relationship has been found between the content of microelements and the tolerance

to the disease by the plant, mainly highlighting the iron content (González, 1996; Quintero, 2002; Liu et al., 2007). In addition, there is evidence that leaf iron application masks typical symptoms of chlorosis in viral diseases in habanero (Lozada-Cervantes et al., 2005), although such symptoms may be associated with nutrition and absorption of nitrates by the plant (Kosegarten et al., 1998; Dordas, 2008).

On the other hand, the components of the environment provided by agronomic management and that supplied by the plant to its host are especially critical for the development of obligate parasites such as viruses (Melugin et al., 1999). The temperature, moisture, excess or nutrient deficiencies reduce vegetative growth and may modify viral concentration in tissues (Fu et al., 2006). The sum of factors that interact between the pathogen, host, environment and time, determines how a diseased plant is affected (Velasco et al., 2001). Several studies have revealed that plastic mulch systems in tomato crops have offered an alternative to the management of diseases such as TSW, because they modify the temperature in the soil, allow a greater development and growth of the plants and delay the time to the occurrence of symptoms of the disease, while increasing yields (Díaz-Pérez et al., 2003; Díaz-Pérez et al., 2007). Therefore, the objective of this research was to evaluate the effect of leaf iron application and the use of plastic mulch on growth, yield, chlorophyll and nitrates in ECP in the cultivation of habanero pepper infected by tospoviruses.

Materials and methods

The experiment was carried out from March 21 To June 20, 2013, and was established in a greenhouse with plastic cover and without temperature control of the Experimental Agricultural Field of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences located in common Nuevo León, BC, coordinates 32° 40’ north latitude and 114° 45’ west longitude. In this region a warm, extreme desert climate prevails and rainfall in winter BW [h’] hs [x’] [e’]), with temperatures of 50 °C during the summer and in winter up to -7 °C, with an average annual temperature of 22.3 °C and an average annual rainfall of 58 mm. The altitude varies from -2 up to 43 meters with a generally flat topography (Ruiz-Corral et al., 2006).

The habanero pepper seedlings were used, which came from seeds planted on polystyrene trays on December 11, 2012 using peat moss substrate (Berger Peat Moss; St. Modestede, Quebec, Canada). The transplant was performed on march 21, 2013 in soil on sowing beds conditioned with chicken coop and sand (1:50 v/v), separated at 1.5 m between rows and a separation between plantlets of 0.3 m distance, to achieve a plantation density of 3.2 plants m-2. The crop was irrigated through a drip irrigation system. Irrigations were applied taking as reference the tensiometer readings placed in the irrigating line. The replacement risks were made each time the tensiometer showed a reading of 25-30 kPa. The fertilization rate used was 120-80-135-100-35 kg ha-1 of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium, respectively, and it was applied in fractional form according to the nutrient absorption curve proposed by Scholberg et al. (2009).

The experimental design used was factorial (4*2*2) with three replications distributed completely randomly. The main plot was the plastic mulching, the sub-plot was the sub-plot and the sub-plot foliar iron doses. The colors of plastic mulch were white, silver, transparent and a witness without quilting. The varieties used were Magnum (Origene Seeds, Gowan, Mexico) and Sun Valley (Sun Valley Seeds, Ca. USA). The first one was infected with IYSV and TSWV (previously identified using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-ELISA, Clark and Adams, 1977) and the second, without viral infection (negative on ELISA); the treatments of iron applied in foliar form were 0 and 5 g L-1. The iron sprays were performed at 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 days after transplantation (DDT) using a solution with chelated iron (Poliquel Fe®; Arista Lifescience, Coahuila, Mexico).

Weekly measurements of plant growth were conducted using the criterion Altland et al. (2003), which included height (A), leaf cover width (Acf) and a growth index formed by the previous variables [(A + Acf + Acf)/3]. In addition, at 30, 45, 60, 75 and 90 ddt, chlorophyll was recorded on freshly mature leaves using the SPAD-502 meter (Soil Plant Analysis Development; Spectrum Technologies, Plainfield, Ill. USA). The results were shown as SPAD index. Additionally was identified the concentration of NO3 - in the petiole cell extract of the leaves in which the SPAD index was determined. The leaves were sampled and peeled off the leaf, the petiole was extracted with garlic press and the NO3 - concentration was determined with the Ion-Cardy portable ion meter (Horiba Corporation, Japan), following the recommendations of Hochmuth (1994).

At the end of the study two harvests of green fruit were carried out at physiological maturity. Each variable was analyzed by means of the statistical program MINITAB 14®. When a difference between treatments or interactions was detected, a comparison test of means was performed (Tukey, p≤ 0.05). Likewise, growth variables were correlated with crop yield.

Results and discussion

Increase

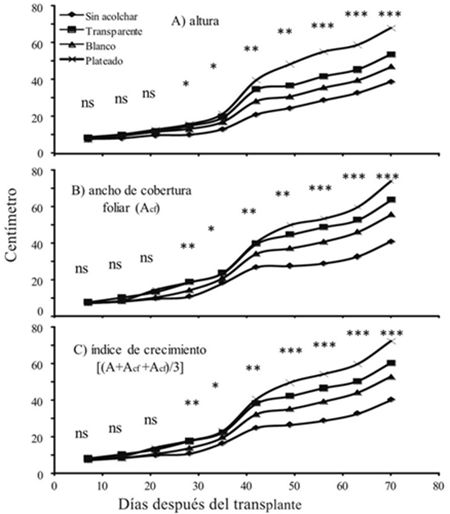

Because there were no statistical differences in growth between treatments of varieties and spray of iron (data not shown), only in the plastic pad treatment, the data concerning the latter variable are presented. During the first 21 DDT, the habanero pepper plants showed the same trend in growth between the treatments of plastic cushion in the variable height, Acf and the growth index (Figure 1).

ns= no significance; *= significance at p≤ 0.05; **= significance at p≤ 0.01; ***: significance at p≤ 0.001.

Figure 1 Growth of habanero pepper in plastic mulch.

The differences between them started at 28 DDT (p≤ 0.05), standing out the silver plated plastic treatment, followed by the transparent padding, the white and finally the treatment without quilting. At the end of the study, the plants with silver padding reached a height of 68.1 cm compared to the control which reached only 38.8 cm. Similar values between treatments were identified for the Acf variable, in which the silver plastic cushion reached 73.9 cm versus the non-quilted control with a value of 40.6 cm. On the other hand, the growth index presented similar values between treatments: 71.9 and 40 cm for the silver padding and the control without quilting, respectively.

In the Table 1 shows the relationship between the weekly growth of plants with plastic mulch and the yield of each crop and the final yield. Because the Acf data, growth index and height showed numerical values very similar to each other, only the results for the height are presented. During the ten measurements was found, the relationship between height and yield of the first harvest and the total harvest (R2≥ 0.49; p≤ 0.05). In contrast, for the case of the second crop, no degree of association was found between the growth height variable (R2≤ 0.44; p˃ 0.05). The type of association between the first crop and the height was linear only up to 42 DDT, and later the trend was in quadratic form. While for the yield of the total crop the linear trend was only during the first 14 DDT and later it was modified to quadratic tendency.

Yield

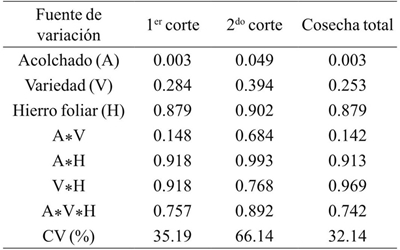

The response in yield of the habanero pepper crop due to plastic mulching, variety and application of foliar iron are shown in Table 2. The mulch variable had a significant effect p≤ 0.05) on harvests. However, the variety, application of foliar iron and its interactions did not affect in any way the yields of the culture of habanero pepper.

Table 2 Analysis of variance of the yield of the habanero pepper cultivation due to plastic mulching, variety and foliar iron application.

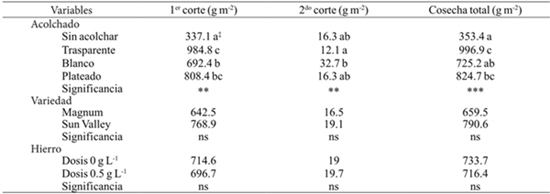

The highest yields were obtained in the first harvest, reaching about 97% of the total yield (Table 3). It was found that using transparent plastic mulch significantly increases performance compared to silver and white mulch. Also, the non-quilting treatment produced only one third (337.1 g m-2) of the yield obtained by transparent and silver-colored quilts (984.8 y 808.4 g m-2, respectively) and about half of what was produced with the quilting white color (692.4 g m-2).

Table 3 Comparison of treatments averages for yield variables in first, second and total harvest of habanero pepper.

++= valores con la misma letra dentro de las columnas son iguales estadísticamente; ns= no significante; **, ***= significancia p≤ 0.01 y p≤ 0.001 respectivamente.

This difference between treatment plastic non-mulch and mulch could be because the latter provide a suitable environment that allows advance the flowering period and mooring fruit in greater numbers than plants without mulch (Aiyelaagbe and Fawusi, 1986; Wien et al., 1993). Among the types of plastic mulch evaluated, the highest yields were obtained by silver-plated and transparent treatments, in this sense Reza et al. (2012) conducting studies of soil temperature in tomato with plastic mulch determined that the soil covered with transparent and silver padding increased the temperature by about 3 °C in relation to white quilts and plastic non-mulch floors.

For the second fruit harvest, the pad yielded the lowest yield was the transparent with 12.1 g m-2, followed by the treatment of silver and non-mulch (16.3 g m-2) and finally by the white treatment (32.7 g m-2). However, in accounting for both harvests, it was identified that the transparent plastic quilting treatment obtained the highest yields with a total of 996.9 g m-2, followed by the silver padding, the white and finally the non-quilting treatment with yields of 824.7, 725.2 and 353.4 g m-2.

The above indicates that the plants cultivated with these colors of quilting had a lower speed of flowering and tie of fruit than the transparent cushioning and the treatment without quilting, nevertheless, they maintained for a longer time the appearance of flower and the tie of fruit, it which allowed the total yields to be equalized between treatments. Similar results have been reported by Decoteau et al. (1989) when evaluating plastic quilting colors in tomato. These researchers found that the early yields of plants with black plastic mulch, had more flowers than plants with white mulch; however, they also mention that when the total yield of the crop was obtained, the quantities of fruit were the same.

The silver-colored and translucent cushions, compared to the white cushioning, increase the soil temperature further and drive the growth of the crop to a greater extent at the beginning of the growing season (Díaz-Pérez and Batal, 2002; Moreno and Moreno, 2008). The above could have happened in the present study, in such a way that the plants grown with silver and transparent color padding outperformed those that grew with white quilting.

On the other hand, it was demonstrated that the effect of infection by tospoviruses and the application of foliar iron had no influence on the fruit yield obtained in any of the cuts made (Table 3). The yields fluctuated between 642.5 and 768.9 g m-2, for the Magnum and Sun Valley varieties, while for plants applied with 0 and 0.5 g L-1 foliar iron were between 714.6 and 696.7 g m-2 respectively. The results found when measuring the application of iron on yield, do not agree with those presented by Lozada-Cervantes et al. (2005). These researchers reported a decrease in virus symptoms as well as an increase in yield and dry matter production in habanero pepper plants subject to the application of 0.5% foliar iron and the use of black plastic mulch.

SPAD Index

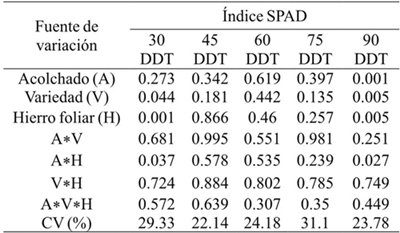

In the Table 4 shows the analysis of variance performed for the variable SPAD index on the application of plastic mulch treatments, variety and foliar iron application. The concentration of chlorophyll in leaves of the habanero pepper crop was significantly affected only at the beginning of the experiment by the variety and the application of iron as well as its interaction (p< 0.05; 30 DDT). In the same way it was significantly affected at the end of the study by plastic mulch, variety and foliar iron (p< 0.05; 90 DDT).

Conclusions

The plants mulch with plastics expressed higher height, foliar cover width and growth index in relation to the non-quilted control, with all the silver-plated quilts standing out.

The use of silver plated and transparent plastic cushions increased the yield in habanero pepper independently of the use of plants infected with tospoviruses and the application of foliar iron.

At the beginning of the experiment, the SPAD index value was affected by the application of foliar iron and by the “tospovirus” effect, however at the end of the experiment, the plastic quilts influenced this variable.

The treatment of white plastic padding followed by silver-colored padding showed an influence on NO3 - concentration in ECP; the lowest values of NO3 - were always found in cultivated plants without plastic mulch.

Literatura citada

MAiyelaagbe, I. O. O. and Fawusi, M. O. A. 1986. Growth and yield response of pepper to mulching. Biotronics. 15:25-29. [ Links ]

Amtmann, A.; Troufflard, S. and Armengaud, P. 2008. The effect of potassium nutrition on pest and disease resistance in plants. Physiologia Plantarum. 133:682-691. [ Links ]

Anjana, S. U. and Iqbal, M. 2006. Nitrate accumulation in plants, factors affecting the process, and human health implications. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 27:45-57. [ Links ]

Atland, J. E.; Gilliam, C. H.; Keever, G. J.; Edwards, J. H.; Sibley, J. L. and Fare, D. C. 2003. Rapid determination of nitrogen status in pansy. Hortscience. 38(4):537-541. [ Links ]

Baq, S.; Schwartz, H. F.; Cramer, C. S.; Havey, M. J. and Pappu, H. R. 2015. Iris yellow spot virus (Tospovirus: Bunyaviridae): from obscurity to research priority. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16(3):224-37. [ Links ]

Cabrera, D.; Sosa, R.; Portal, O.; Alburquerque, Y.; González, J. E. and Hernández, R. 2009. Alterations induced by papaya ringspot potyvirus on chlorophyll content in papaya (Carica papaya L.) leaves. Fitosanidad. 13(2):125-126. [ Links ]

Carter, G. A. and Knapp, A. K. 2001. Leaf optical properties in higher plants: linking spectral characteristics to stress and chlorophyll concentration. Am. J. Bot. 88(4):677-684. [ Links ]

Clark, M. F. and Adams, A. N. 1977. Characteristics of the microplate method of enzyme-linked inmunosorbent assay for the detection of plant viruses. J. General Virol. 34(3):475-483. [ Links ]

Decoteau, D. R.; Kasperbauer, M. J. and Hunt, P. G. 1989. Mulch surface color affects yield of freshmarket tomatoes. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 114(2):216-219. [ Links ]

Diaz-Pérez, J. C. and Batal, K. D. 2002. Colored plastic mulch affects tomato growth and yield via changes in root-zone temperature. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 127(1):127-136. [ Links ]

Diaz-Pérez, J. C.; Batal, K. D.; Granberry, D.; Bertrand, D. and Giddings, D. 2003. Growth and yield of tomato on plastic film mulches as affected by tomato spotted wilt virus. HortScience. 38(3):395-399. [ Links ]

Díaz-Pérez, J. C.; Gitaitis, R. and Mandal, B. 2007. Effects of plastic mulches on root zone temperature and on the manifestation of tomato spotted wilt symptoms and yield of tomato. Scientia Hortic. 114(2):90-95. [ Links ]

Dordas, C. 2008. Role of nutrients in controlling plant diseases in sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 28(1):33-46. [ Links ]

Fanigliulo, A.; Viggiano, A.; Gualco, A. and Crescenzi, A. 2014. Control of viral diseases transmitted in a persistent manner by thrips in pepper (tomato spotted wilt virus). Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 79(3):433-7. [ Links ]

Fu, D. Q.; Zhu, B. Z.; Zhu, H. L.; Zhang, H. X.; Xie, Y. H. and Jiang, W. B. 2006. Enhancement of virus-induced gene silencing in tomato by low temperature and low humidity. Mol. Cells. 21(1):153-160. [ Links ]

Gill, S. S. and Tuteja, N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant physiology and biochemistry. 48(12):909-930. [ Links ]

González, R. M. 1996. Efecto de niveles nutrimentales de las infecciones de los virus marchitez manchada del tomate y jaspeado del tomate (Licopersicum esculentum Mill.). Tesis de maestría. Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 114 pp. [ Links ]

Hochmuth, G. 1994. Plant petiole sap-testing for vegetable. Fla. Coop. Ext. Serv. Special Series CV00400. [ Links ]

Huber, D. M. and Jones, J. B. 2013. The role of magnesium in plant disease. Plant and Soil. 368(1):73-85. [ Links ]

Kosegarten, H.; Wilson, G. H. and Esch, A. 1998. The effect of nitrate nutrition on iron chlorosis and leaf growth in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Eur. J. Agron. 8(3-4):283-292. [ Links ]

Liu, G.; Greenshields, D. L.; Sammynaiken, R.; Hirji, R. N.; Selvaraj, G. and Wei, Y. 2007. Targeted alterations in iron homeostasis underlie plant defense responses. J. Cell Sci. 120(4):596-605. [ Links ]

Lozada, C. D. M.; Tun, S. J. M.; Cristóbal, A. J. y Pérez, G. A. 2005. Acolchado negro y niveles de fierro para reducir la severidad de geminivirus en chile habanero (Capsicum chinense Jacq.). In: Memorias de I Congreso Internacional de Casos Exitosos de Desarrollo Sostenible del Trópico. Boca del Río, Veracruz, México. 65-67 pp. [ Links ]

Macías, R. H.; Muñoz, V. J. A.; Velásquez, V. M. A.; Potisek, T. M. D. C. y Villa-Castorena, M. M. 2013. Chile habanero: descripción de su cultivo en la península de Yucatán. Revista Chapingo Serie Zonas Áridas. 12(2):37-43. [ Links ]

Margaria, P.; Bosco, L.; Vallino, M.; Ciuffo, M.; Mautino, G. C.; Tavella, L. and Turina, M. 2014. The NSs protein of tomato spotted wilt virus is required for persistent infection and transmission by Frankliniella occidentalis. J. Virol. 88(10):5788-802. [ Links ]

Melugin, C. S.; Scherm, H. and Chakraborty, S. 1999. Climate change and plant disease management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37:399-426. [ Links ]

Moreno, M. M. and Moreno, A. 2008. Effect of different biodegradable and polyethylene mulches on soil properties and production in a tomato crop. Sci. Hortic. 116:256-263. [ Links ]

Pérez, M. L.; Rico, E. J.; Ramírez, J. R. M.; Sánchez, J. L. P.; Asencio, J. T. I.; Díaz, R. P. y Rivera R. F. B. 2004. Identificación de virus fitopatógenos en cultivos de importancia económica en el estado de Guanajuato, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 22(2):187-197. [ Links ]

Pennazio, S.; Roggero, P. and Conti, M. 1996. Yield losses in virus-infected plants. Arch. Phytopatol. Plant Protec. 30(4): 283-296. [ Links ]

Quintero, B. J. A. 2002. Resistencia de Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. al virus de la marchitez manchada del tomate (TSWV). Tesis Doctoral. Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 119 p. [ Links ]

Reza, H.R.; Hassankhan, F. and Rafezi, R. 2012. Effect of colored plastic mulches on yield of tomato and weed biomass. Inter. J. Environ. Sci. Develop. 3(6):590-593. [ Links ]

Roggero, P.; Tavares de Melo, A. M.; Moreira, S. R. and Colariccio, A. 2003. The search of resistance to tospovíruses in the genus Capsicum sp. Hortic. Bras. 2(21):335-337. [ Links ]

Ruiz, C. J. A.; Díaz, P. G.; Guzmán, R. S. D.; Medina, G. G. y Silva, S. M. M. 2006. Estadísticas climatológicas básicas del estado de Baja California (período 1961-2003). Libro técnico Núm. 1. Centro de Investigación Regional del Noroeste, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones, Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. SAGARPA. 167 p. [ Links ]

SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera). 2013. Información estadística de la producción agrícola mexicana. http://www.siap.sagarpa.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Scholberg, J. M.; Zotarellibd, L.; Tubbsc, R. S.; Dukesb, M. D. and Muñoz, C. R. 2009. Nitrogen uptake efficiency and growth of bell pepper in relation to time of exposure to fertilizer solution. Comm. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 40(13-14):2111-2131. [ Links ]

Velasco, V. V. A.; Alcántar, G. G.; Sánchez, P. G.; Estañol, E. B.; Zavaleta, E. M.; Cárdenas, E. S.; Rodríguez, R. M. y Martínez, M. G. 2001. Efecto de N, P y K en plantas de chile jalapeño infectadas con el virus jaspeado del tabaco. Terra Latinoam. 2:117-125. [ Links ]

Received: February 2017; Accepted: March 2017

texto em

texto em