Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 spe 16 Texcoco Mai./Jun. 2016

Articles

Chemical and mineral composition of leucaena associated with star grass during the rainy season

1Ciencias en Innovación Ganadera-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 38.5, Chapingo, Estado de México, C. P. 56230. México. Tel: 595 952 1621. (itzel_bjoe@hotmail.com; agronojuan@hotmail.com).

2Departamento de Zootecnia-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 38.5, Chapingo, Estado de México, C. P. 56230. México. Tel: 595 952 1621. (mhuertab@taurus.chapingo.mx; alarab_11@hotmail.com; rangelsr@correo.chapingo.mx).

The aim of this study was to determine the chemical and mineral composition of the leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala Lam. de Wit) and star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst) associated in an intensive silvopastoral system 35, 42, 49, 56, 63 and 70 day old sprouts during the rainy season, in the Huasteca potosina region of Mexico. The variables evaluated were the percentage of EE, PC, FDA, FDN, Ca, Mg, Na, K and P, ratio Ca:P and ppm Cu, Zn and Fe. The results showed significant differences (p< 0.05) by effect of age of suckers for the FDN and Ca which were higher at day 49 while Na and P decreased with increasing age of suckers. In contrast, the concentration of FDA, Cu and Fe increased with increasing age of the volunteers (p< 0.05). There were differences between the forage species (p< 0.05) for most of the variables studied, except for Na, K and Zn minerals. Leucaena had higher content of EE, PC, Ca, Mg, Cu and Fe; but the star grass had higher content of FDN, FDA and Ca:P ratio. The age of the volunteers interacted with forage species for content FDN, Na, K and Zn. The deficiencies Cu, Zn and P in forages studied were found. It is concluded that leucaena star grass association with improved chemical and mineral composition of edible foliage.

Keywords: age of suckers; forage species; intensive silvopastoral system; tropical forages

El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la composición química y mineral de la leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala Lam. de Wit) y el pasto estrella (Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst) asociados en un sistema silvopastoril intensivo a 35, 42, 49, 56, 63 y 70 días de edad de los rebrotes, durante la época de lluvias, en la región Huasteca potosina de México. Las variables a evaluar fueron los porcentajes de EE, PC, FDA, FDN, Ca, Mg, Na, K y P, relación Ca:P y ppm de Cu, Zn y Fe. Los resultados mostraron diferencias significativas (p< 0.05) por efecto de la edad de los rebrotes para el contenido de FDN y Ca los cuales fueron mayores al día 49 mientras Na y P disminuyeron al incrementarse la edad de los rebrotes. Contrariamente, la concentración de FDA, Cu y Fe se incrementaron a mayor edad de los rebrotes (p< 0.05). Hubo diferencias entre las especie forrajera (p< 0.05) para la mayoría de las variables estudiadas, excepto para los minerales Na, K y Zn. Leucaena tuvo mayor contenido de EE, PC, Ca, Mg, Cu y Fe; pero el pasto estrella tuvo mayor contenido de FDN, FDA y relación Ca:P. La edad de los rebrotes interaccionó con las especies forrajeras para el contenido de FDN, Na, K y Zn. Se encontraron deficiencias de Cu, Zn y P en los forrajes estudiados. Se concluye que la asociación leucaena con el pasto estrella mejoró la composición química y mineral del follaje comestible.

Palabras clave: especies forrajeras; edad de los rebrotes; forrajes tropicales; sistema silvopastoril intensivo

Introduction

In tropical and subtropical regions there is a shortage of quality food (Pound and Martínez, 1985). Although tropical grasses have a high photosynthetic efficiency resulting in higher rates of biomass production, they have anatomical, biochemical and physiological characteristics that make them less efficient than temperate grasses. Under these conditions the tropical grasses are low in nutritional quality, in terms of energy , protein and mineral content (Hernández et al., 2000).

The leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala Lam. de Wit) is a tropical legume high nutritional value for ruminants and is a valuable forage as an ingredient in rations for livestock. A silvopastoral system is an option livestock production involving the use of woody perennials (trees or shrubs) that interact with traditional fodder and animals in a comprehensive management system (Pezo and Ibrahim, 1998). This system is characterized by the diversification of its products and benefits, which makes them more favorable land use, achieving a proper balance between productivity, stability, biodiversity and environmental self-regulation (Marlats et al., 1995).

Harnessing photosynthetic capacity of the multiple layers of plants intended to provide food for animals, it represents the greatest opportunity to intensify livestock production sustainably (Ibrahim et al., 2006). The aim of this study was to determine the chemical and mineral composition of the leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala Lam. de Wit) and star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst) associated in an intensive silvopastoral system at different age of suckers.

Materials and methods

Characteristics of the study area

This study was conducted in the Production Unit "The Gargaleote" property of Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, located in the municipality of Tamuin, San Luis Potosí, in the region known as "The Huasteca Potosina in Mexico". The study area is located between the geographical coordinates 24° 29' and 21° 10' north latitude and 98° 20' and 102° 18' west longitude, 40 meters (INEGI, 2005); It presents a climatic condition Aw''o type (e) described as hot subhumid with summer rains, with annual average temperature of 26.8 °C and annual rainfall of 927.7 mm (García, 2004). Soils are vertisoles and fluvisoles (according to FAO-UNESCO classification), deep and well drained, textured silt or silty clay sandy, with alkaline pH above 7.5 due to geological origin.

Features of parcels

The study was conducted on a hectare of land associating star grass and leucaena established during the months of July to December 2010 in an intensive silvopastoral system (Solorio et al., 2009). The experimental plot was divided into 18 batches of 11.11 x 50 m (555.55 m2). Three batches selected randomly were assigned to one of six treatments that corresponded to the age of suckers: 35, 42, 49, 56, 63 and 70 days from the recent pruning of leucaena at the beginning of the rainy season.

Collection and analysis of samples

The sampling consumable foliage of each forage species was performed on each batch in triplicate, in three sampling sites 3.2 m2 randomly selected by the method of simulated grazing Hand Plucking (Penning, 2004) considering the behavior of grazing sheep. The samples were dried in a forced air oven at 65 °C to obtain the dry matter yield and subsequently crushed to 2 mm to determine dry matter (MS), organic matter (MO), ash (CEN), ether extract (EE), total protein (PC) using the methodology of the AOAC (2000); neutral detergent fiber (FDN) and acid detergent fiber (FDA) using the method of Van Soest et al. (1991). The concentration of each nutrient is adjusted using the proportions 52:48 to leucaena and star grass, respectively, from dry matter yield obtained from each forage species during the rainy season. Since the inorganic fraction of each forage species content of Ca, Mg, Na, K, Cu, Fe and Zn it was determined by the method of atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Fick et al., 1979) and P by colorimetry (Clesceri et al., 1992).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM) of SAS (2004) with the following statistical model:

Where: Yij= value of the response variable corresponding to the i-th age of regrowth in the jth forage species, μ= general mean Eri effect of the i-th age of regrowth (i= 35, 42, 49, 56, 63, 70), EFj= effect of j-th forage species (leucaena, grasses) and εijk= random error ~ NIID (0, σ2e). Tukey test (Steel et al., 1997) was used to compare treatment means.

Results and discussion

Effect of age of the volunteers (ER) in chemical and mineral composition of leucaena and star grass

There were no differences (p> 0.05) EE and PC between the ages of regrowth. The age of the volunteers showed differences (p> 0.05) in the percentage of FDN and FDA. The age of the volunteers showed differences (p> 0.05) in the concentrations of Ca, Mg, Na, P, Cu and Fe. In the Table 1 shows the effects of the age of the volunteers (ER) in the variables of chemical composition and leucaena ore and star grass associated in an intensive silvopastoral system.

Table 1 Effect of the age of the volunteers (ER) on the chemical composition and mineral leucaena and star grass associated in an intensive silvopastoral system.

EE= extracto etéreo; PC= proteína cruda; FDN= fibra detergente neutro; FDA= fibra detergente ácido; ab= medias con diferente literal muestran diferencias significativas entre columnas; y= error estándar de la media; x= nivel de significancia.

Ether extract (EE) and crude protein (PC)

Contrary to what mentioned by Lorenzo et al. (2012) who report that can produce a dilution process nitrogen (N), in which the ratio of the PC with other components of the dry matter (MS) decreases due to the growth achieved by the grass, the conditions favorable light, temperature and humidity. According Jarillo- Rodríguez et al. (2011) diluting the protein can be attributed to increased production of MS, which increases the percentage of stems and increased cell wall content, as they are elements that affect the digestibility of grasses and PC. However, in this case the similar content of EE and PC between the ages of flare- ups can be attributed to a positive response from the leucaena associated with star grass providing fixed nitrogen to the soil and other nutrients from deeper soil layers allowing the tissue plant of both forage species maintained high nutritional quality (Sánchez et al., 2007).

Neutral detergent fiber (FDN) and acid detergent fiber (FDA)

The content of FDA, older increased to 54.8% cut to 70 days; FDN and a higher percentage at 49 days with 69% was observed; however, these increases were moderate, allowing the plant tissue of both forage species maintained a higher nutritional quality (Sánchez et al., 2007). These results agree with those reported by Lara et al. (2013) who observed an increase in the NDF and FDA of leucaena and star to increased pasture regrowth age, but differ with Maya et al. (2006) who found no difference between periods of cut for the same components of the cell wall of both forages; however, they differ from those obtained by Maya et al. (2005) who found no significant differences for the components of the cell wall between cutting periods. However, they have been reported increases in the concentration of fibers older cutting, because when mature tissues lignification process is given, increasing the fibrous fraction of the cell wall (Martínez and Reyes, 2013).

Minerals

The concentrations of Ca, P and Cu decreased with increasing age of the volunteers, while Fe, Na and Mg increased, showing the highest to 70 days after pruning values, which can be explained because several of these elements remain constant in mature organs and stems of plants (Gomide and Zometa, 1976). According to Minson (1990) there is a greater concentration of P in tender forages mature forages compared with corresponding to increased accumulation of this element during active growth of pastures in wetter conditions on the ground. The Ca:P ratio showed no significant differences due to the age of suckers, however, increased calcium and phosphorus decreased as the plant matured.

The PC levels in all ages of the sprouts were higher or adequate to meet the requirements of sheep and cattle grazing (Sánchez and Faria-Marmol, 2008). The content of NDF and FDA are among the normal standards reported by other researchers comparing legumes and grasses in different age of the volunteers (Nouel et al., 2005; Sánchez et al., 2007). As for the minerals studied considering the minimum requirements for minerals in the diet of sheep (NRC, 1985), in the order of 0.3, 0.1, 0.1, 0.5, 0.25% and 2.0:1.0 Ca, Na, Mg, K, P and Ca:P ratio, respectively, and Cu, Fe and Zn in the order of 10, 50 and 30 ppm, forages analyzed showed deficiencies of Ca, P, Cu and Zn, and a lower ratio Ca:P.

This may be due to low levels of these minerals in the soil, as well as greater dilution of minerals due to the rainy season. The low concentrations of Cu, Zn and P, as well as high concentrations of Fe and K in forages in the rainy season based on the requirements of sheep, coincides with previously reported by Muñoz- González et al. (2014) who they reported concentrations of Cu, Fe and Zn of 4.93, 253 and 31 mg/kg and Ca, Mg, Na, K and P of 0.31, 0.23, 0.09, 196 and 0.22%, respectively, in tropical forages the rainy season in the northeastern Chiapas; these authors mention that forages have lower concentrations of minerals in the rainy season compared to the dry season.

Other studies in Mexico Morales et al., (2007); Domínguez- Vara and Huerta Bravo (2008) in temperate forages; Vieyra-Alberto et al., (2013); Muñoz-González et al. (2014) in forages tropical climate reported variations in the concentration of minerals between seasons, so the development of further research is needed to determine the composition nutrimental of forages evaluated in this study during the dry season. Supplementation is recommended with Cu, Zn and P during the rainy season to correct any deficiencies in animals that consume the feed in the study area.

Effect of forage species (EF) in the chemical and mineral composition of leucaena and star grass

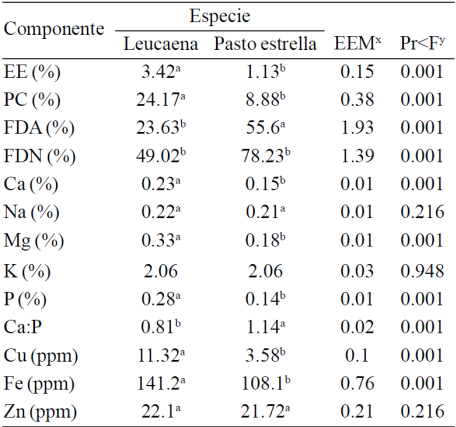

In the Table 2 shows the effects of forage species on the chemical and mineral composition are shown.

Table 2 Effect of forage species (EF) on the chemical and mineral composition of leucaena and star grass in an intensive silvopastoral system.

EE= extracto etéreo; PC= proteína cruda; FDN= fibra detergente neutro; FDA= fibra detergente ácido; ab= medias con diferente literal muestran diferencias significativas entre columnas; x= error estándar de la media; y= nivel de significancia.

There were significant differences (p< 0.05), the content of EE, PC, FDA, FDN, Ca, Mg, ratio Ca:P, Cu and Fe between leucaena and star grass, however, concentrations of Na, P, K and Zn were similar for both species.

Ether extract (EE) and crude protein (PC)

The Leucaena showed higher values for EE and PC. The EE was 203% higher in leucaena the percentage EE star grass, while PC was 175% higher in the legume in the grass. In leucaena Clavero (2011) reported higher contents of PC to this study with 30.4%. This can be linked to that legumes are fixers N with deep roots that increase the availability of nutrients through biological fixation, recycling or pumping nutrients from deeper layers to the surface of the soil (especially in dry areas) and accumulation organic matter in the soil (Rao et al., 1998). In addition, compared with species of tropical grasses, legumes are capable of synthesizing high levels of PC with a relatively low rate of decline in this component as the plant matures (Rincón, 2011).

Neutral detergent fiber (FDN) and acid detergent fiber (FDA)

Leucaena showed lower values (p< 0.05) for the components of the cell wall (FDA and FDN). The content of FDN and FDA was lower in leucaena than star grass (135 and 59%) respectively. The lowest levels of fiber in legumes benefit has been observed nutrient intake in animals. For example, it has been observed that in sheep supplemented with legumes, consumption of organic matter (MO) and PC increase (Abreu et al., 2004), according Weisbjerg and Soegaard (2008) increased consumption of legumes compared with grasses it may be, inter alia, to differences in the chemical structure and the fiber content.

This is attributed to that legumes have a lower concentration of total FDN, but a higher concentration of lignin than grasses, and this lignin is linked to a low proportion of the indigestible NDF, so there is a greater proportion of indigestible FDN in legumes than in grasses. According to Wilson and Kennedy (1996) in legumes, lignin is found only in the xylem, so this is entirely indigestible, while in other tissues no lignin and the cell walls are completely digestible.

However, according Buxton and Russell (1988) in grasses lignin is distributed in all tissues of the plant, except in the phloem, therefore, the least amount of lignin which have grasses protect more of walls rumen cell, causing the rate of digestion of the cell wall is less than in legumes. This may relate to the positive effects that different studies have shown the inclusion of leguminous species and their effect on milk production in different ruminant species (Razz and Clavero, 1997; Steinshamn, 2010) and weight gain (Combellas et al., 1999; Verdolak and Zorate, 2008; Benavides-Calvache et al., 2010).

Minerals

For Ca, Cu and Mg, the content was 46, 86 and 31% higher than in leucaena that star grass, while the Ca:P ratio was 43% higher in star grass. Lara et al. (2013) reported greater intake of Ca and P in leucaena, while Vivas et al. (2012) observed in leucaena highest percentage of Ca and Cu compared to other grasses; while Gomide and Zometa (1976) observed higher percentage of Mg in the legume. The iron content was high in both forage species, even above the critical level for ruminants (McDowell and Arthington, 2005). The Fe concentrations in grasses of this study are consistent with those of Vieyra-Alberto et al. (2013) who reported an average of 116.5 ppm of Fe; however, reported lower concentrations of K and P in the order of 0.15 and 0.07%, respectively, in grasses of the Huasteca Potosina, Mexico.

Muñoz et al. (2014) reported concentrations of minerals in different grass species in southeastern Mexico in the order of 0.36, 0.27, 0.13, 1.66, 0.2% of Ca, Mg, Na, K and P, respectively, and 6.18, 274.25, 36.5 ppm of Cu, Fe and Zn, respectively, highlighting high levels of Fe and low levels of Cu and P, with respect to the requirement of cattle. Insufficient levels of P, Cu, Zn and tropical forages were in were reported in other regions of the country (Castañeda, 2012), although Cu deficiency and is usually correspond to alkaline soils and antagonism with high levels of Fe, S and Mo (Suttle, 2010). Even with these problems, the silvopastoral system leucaena-star grass, increases the mineral content and quality of the diet of ruminants grazing.

Minson (1990) mentions that there are differences in forage (dry matter) of different species and different climate, for example in concentrations of Cu in legumes tropical and temperate with 3.9 and 7.8, Zn 40 and 38 mg kg-1, respectively; in grasses of tropical and temperate climate with concentrations of 7.8 and 4.7 Cu, Zn 36 and 34 mg kg-1, respectively. To Suttle (2010) provide more legumes than grasses minerals which could explain the balance of minerals observed in our study. However, the Ca: P ratio was low which can cause an imbalance between the two minerals (Ceballos, 2004).

As for the minimum requirements of minerals sheep (NRC, 1985) leucaena and star grass presented low concentrations of Ca; however, Huerta (2003) Ca deficiency in ruminants grazing grasses is very rare and never occurs in legumes. Both forages also deficient Zn also presents the grass P and Cu concentrations under the requirements of ovine.

It is necessary to mention the importance of these minerals are in the body of animals, that Cu is a necessary component of important antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) and ceruloplasmin (Waldron, 2010) to prevent oxidation and peroxidation of tissue (Spears and Weiss 2010), while Zn is necessary for the synthesis of metallothionein that helps removing free radicals and maintain the integrity of epithelial tissue and the formation of keratin which provides a physiological barrier against infection (O'Rourke 2009). It is important to mention the increased capacity of extraction of nutrients by leucaena, so it is necessary that new will continue investigating what possible benefits from their association with other forages.

Conclusion

The cellular components: ether extract and crude protein were not affected by the age of suckers in both forage species; however, leucaena had more fat and protein than star grass. Both species associated increased availability of dietary protein. The cell walls increased the older the edible foliage in both species, but the content of NDF and FDA was higher in star grass. The concentration of Ca, P and Cu decreased cutting at an older age, while magnesium, iron and sodium increased the older the foliage because these minerals build up in organs and stems of mature plants. The Ca:P ratio was higher in star grass because of its lower calcium content in said fodder. Ca, P, Cu and Zn should be supplemented during the rainy season grazing ruminants leucaena associated with star grass. There were deficiencies of Cu, Zn and P in forages studied so supplementation animals consuming these forages is recommended with these minerals.

Literatura citada

Abreu, G. D.; Schuch, L. O. e Maia, M. D. S. (2004). Análise do crescimento de aveia branca (Avena sativa L.) em cultivo companheiro com leguminosas forrageiras. Revista Agronomia. Seropédica. 38(1):16-21. [ Links ]

AOAC. 1990. Official methods of analysis.15th.Ed. Arlington, VA, US. [ Links ]

Benavides-Calvache, C. A.; Valencia-Murillo, M. y Estrada-Álvarez, J. 2010. Efecto de la veranera forrajera (Cratylia argentea) sobre la ganancia de peso de ganado doble propósito. Vet. Zootec. 4:23-27. [ Links ]

Buxton, D. R. and Russell, J. R. 1988. Lignin constituents and cell-wall digestibility of grass and legume stems. Crop Sci. 28:553-558. [ Links ]

Castañeda, C. S. 2012. Diagnóstico mineral de ganado bovino en condiciones de trópico húmedo. Tesis de Maestría. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 71 p. [ Links ]

Ceballos, M. A. 2004. Desequilibrios minerales de bovinos en sistemas silvopastoriles, Grupo de Investigación Salud Productiva en Bovinos, Porcinos y Equinos, Universidad de Caldas. Manizales, Colombia. [ Links ]

Clavero, T. 2011. Agroforestería en la alimentación de rumiantes en América Tropical. Revista de la Universidad del Zulia. Ciencias del Agro, Ingeniería y Tecnología. 2:11-35. [ Links ]

Clesceri, S. L.; Greenberg, E. A. y Trusseli, R. R. 1992. Métodos Normalizados para el Análisis de Aguas Potables y Residuales. Ed. Díaz De Santos. España. pp:187-195. [ Links ]

Combellas, J.; Ríos L.; Osea, A. y Rojas, J. 1999. Efecto de la suplementación con follaje de leguminosas sobre la ganancia en peso de corderas recibiendo una dieta basal de pasto de corte. Rev. Fac. Agron. (LUZ) 16: 211-216. [ Links ]

Domínguez-Vara, I. A. y Huerta-Bravo, M. 2008. Concentración e interrelación mineral en suelo, forraje y suero de ovinos durante dos épocas en el Valle de Toluca, México. Agrociencia. 42: 173-183. [ Links ]

Fick, K., R.; Mcdowell, L. R.; Miles, P. H.; Wilkinson, N. S.; Funk, J. D.; Conrad, J. D. y Valdivia, R. 1979. Métodos de Análisis de Minerales para Tejidos de Plantas y Animales. Segunda edición. Universidad de Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA. 358 p. [ Links ]

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen (5a ed.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Geografía. México. [ Links ]

Gomide, J. A. y Zometa, A. T. 1976, Composición mineral de los forrajes cultivados bajo condiciones tropicales. Departamento de Ciencia Animal. Universidad de Florida. 39-46 pp. [ Links ]

Hernández, D.; Carballo, M. y Reyes, F. 2000. Reflexiones sobre el uso de los pastos en la producción sostenible de leche y carne de res en el trópico. Pastos y Forrajes 23:269-284. [ Links ]

Huerta, B. M. 2003. Signos de deficiencia y respuestas a la suplementación mineral del ganado en pastoreo. In: Memoria del Curso Suplementación Mineral de Ganado en Zonas Áridas y Semiáridas. Agosto de 2003. Monterrey, N. L. pp: 48-64. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, M.; Villanueva, C.; Casasola, F. y Rojas, J. 2006. Sistemas silvopastoriles como una herramienta para el mejoramiento de la productividad y restauración de la integridad ecológica de paisajes ganaderos. Pastos y Forrajes. 29:383-419. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2005. México en Cifras: Información Nacional por Entidad Federativa y Municipios, San Luis Potosí. México. [ Links ]

Lara, B. A.; Reyes, C. A.; Martínez, M. M.; Miranda, R. L. A.; Huerta, B., M. y Krishnamurthy, L. 2013. Composición nutrimental de la leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala Lam. De Wit) asociada con pasto estrella (Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst) en la región huasteca potosina de México. Memorias: XXIII Reunión de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Producción. La Habana, Cuba. [ Links ]

Marlats, R. M.; Denegrí, G.; Ansín, O. E y Lanfranco, J. W. 1995. Sistemas silvopastoriles: Estimación de beneficios directos comparados con monoculturas en la pampa ondulada. Argentina. Agroforestería en las Américas. 8:20-25. [ Links ]

Maya, G. E.; Durán, C. V. y Ararat, J. E. 2006. Valor nutritivo del pasto estrella solo y en asociación con leucaena a diferentes edades de corte durante el año. Acta Agronómica. 54(4):41-46. [ Links ]

McDowell, L. R. y Arthington, J. D. 2005. Minerales para rumiantes en pastoreo en regiones tropicales. 4a. Ed. Universidad de Florida, Grinnesville, Florida. 94 p. [ Links ]

Morales, A. E.; Domínguez, V. I., González-Ronquillo, M.; Jaramillo, E. G.; Castelán, O. O.; Pescador, S. N. y Huerta, B. M. 2007. Diagnóstico mineral en forraje y suero sanguíneo de bovinos lecheros en dos épocas en el valle central de México. Técnica Pecuaria México. 45(3): 329-344. [ Links ]

Muñoz-González, J. C.; Huerta-Bravo, M.; Rangel-Santos, R.; Lara- Bueno,A. and De la Rosa-Arana, J. L. 2014. Mineral assessment of forage in mexican humid tropics. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems. 17:285-287. [ Links ]

Nouel, G.; Prado, M.; Villasmil, F. y Rincón, J. 2005. Consumo y digestibilidad de raciones con leguminosas del semiárido, Leucaena y paja de arroz amonificada para cabras. In: Memorias de la XIX Reunión de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Producción. Tampico, México. 17: 497-499. [ Links ]

NRC. 1985. Nutrient Requirements of Domestics Animals. Nutrients Requirements of Sheep. Sixth Revised Edition. National Academies Press, Washington, D. C. USA. 112 p. [ Links ]

Penning, P. D. 2004. Animal-based techniques for estimating herbage intake. Herbage intake handbook. 2:53-94. [ Links ]

Pezo, D. e Ibrahim, M. 1998. Sistemas silvopastoriles. Módulo de enseñanza agroforestal No. 2. IICA/CATIE. 204 p. [ Links ]

Pound, B. y Martínez, C. L. 1985. Leucaena: su cultivo y utilización. Overseas Development Administration London. 289 p. [ Links ]

Rao, M. R.; Nair, P. K. and Ong, C. K. 1998. Biophysical interactions in tropical agroforestry systems. Agroforestry Systems. 38:3-50. [ Links ]

Razz, R. y Clavero, T. 1997. Producción de leche en vacas suplementadas con harina deGliricidia sepium. Arch .Latinoam. Prod. Anim. 5(1):127-128. [ Links ]

Rincón, J. 2011. Establecimiento y manejo de leguminosas arbóreas de importancia forrajera en zonas semiáridas de Venezuela. En: Innovación & Tecnología en la Ganadería Doble Propósito. González-Stagnaro C, Madrid-Bury N, Soto Belloso E (eds). Fundación GIRARZ. Ediciones Astro Data S.A. Maracaibo, Venezuela. Capítulo XXIX: 277-289. [ Links ]

Sánchez A. G. y Faria M. J. 2008. Efecto de la edad de la planta en el contenido de nutrientes y digestibilidad de Leucaena leucocephala. Zootecnia Tropical. 26:133-139. [ Links ]

Sánchez, G. A.; González, C. J. y Faría, M. J. 2007. Evolución comparada de la composición química con la edad al corte en las especies Leucaena leucocephala y L. trichodes. Zootecnia Tropical. 25:233-236. [ Links ]

SAS. 2004. SAS/STAT 9.1. User’s Guide. Vol. 1-7. SAS Publishing. Cary, NC, USA. 5180 p. [ Links ]

Solorio, S. F.; Bacab, H.; Castillo, J. B.; Ramírez, L. y Casanova F. 2009. Potencial de los sistemas silvopastoriles en México. In II Congreso sobre sistemas silvopastoriles intensivos. Morelia, Michoacán, México. 10 p. [ Links ]

Steel, R. G. D.; Torrie, J. H. and Dickey, D. A. 1997. Principles and Procedures of Statistics: A Biometrical Approach. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Series in Probability and Statistics. USA [ Links ]

Steinshamn, H. 2010. Effect of forage legumes on feed intake, milk production and milk quality-a review. Animal Science Papers and Reports. 28:195-206. [ Links ]

Suttle, N. F. 2010. Mineral Nutrition of Livestock. 4th Edition. CABI Publishing. UK. 587 p. [ Links ]

Van Soest, P. J.; Robertson, J. B. y Lewis, B. A. 1991. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. Journal of Dairy Science. 74:3583-3597. [ Links ]

Verdoljak, J. O. y Zórate, P. 2008. Uso de Leguminosas Tropicales en la Alimentación de Ovinos de Pelo. INTA-Argentina. Informe de Investigación. Obtenido el 20 de agosto de 2013. http://inta. gob.ar/personas/verdoljak.juan. [ Links ]

Vieyra-Alberto, R.: Domínguez-Vara, I. A.; Olmos-Oropeza, G.; Martínez-Montoya, J. F.; Borquez-Gastelum, J. L.; Palacio- Nuñez, J.; Lugo, J. A. y Morales-Almaráz, E. 2013. Perfil e interrelación mineral en agua, forraje y suero sanguíneo de bovinos durante dos épocas en la huasteca potosina, México. Agrociencia. 47:121-133. [ Links ]

Vivas, M. E. F.; Rosado, R. G.; Castellanos, R. A.; Heredia, A. M. y Cabrera, T. E. 2012. Contenido mineral de forrajes en predios de ovinocultores del estado de Yucatán. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias. 2:465-475. [ Links ]

Weisbjerg, M. R. and Soegaard, K. 2008. Feeding value of legumes and grasses at different harvest times. In: Proceedings of 22nd General meeting of the European Grassland Federation. Hopkins A, Gustafson T, Nilsdotter-Linde N, Spörndly E (eds). Grassland Science in Europe. 13: 513-515. [ Links ]

Wilson, J. R. and Kennedy, P. M. 1996. Plant and animal constraints to voluntary feed intake associated with fibre characteristics and particle breakdown and passage in ruminants. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 47:199-225. [ Links ]

Received: March 2016; Accepted: May 2016

texto em

texto em