Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 spe 15 Texcoco Jun./Ago. 2016

Articles

Social networks and trust between producers of rambutan in the Soconusco, Chiapas

1Centro de Investigaciones Económicas Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM)-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 38.5, C. P. 56230. Chapingo, Estado de México. México. (arturoflorestrejo@gmail.com; jaguilar@ciestaam.edu.mx; redes.rendon@gmail.com; sermarber@gmail.com).

This research analyzes the influence of existing social relations within a group of 22 producers of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) of Soconusco, Chiapas in 2014. The joint actions were analyzed related to improving the marketing of their product. Building scale relational links was used for collective work composed identification levels, contribution, collaboration, cooperation and partnership. Through the analysis of social networks (ARS) the number of relationships, and the density indicators and index for each level of centralization were identified. The results indicate a significant decline in relations present (47, 24, 11, 6, 3) in ascending order of the assessed levels; the higher the ratio, the lower their number. The lowest densities were reported in collaboration levels (1.6%), cooperation (0.09%) and association (0.07%). a strong social dislocation is observed mainly attributable to previous organizational experiences, individualism, and different visions of productive activity. a scenario of mistrust and poor commitment among members that negatively influences the collective enterprises is observed. It is concluded that it is necessary to take actions that promote greater social articulation, confidence and organizational culture among producers, before or on par with commercial integration initiatives.

Keywords: construction of social ties; social network analysis; trust; work together

La presente investigación analiza la influencia de las relaciones sociales existentes al interior de un grupo de 22 productores de rambután (Nephelium lappaceum) del Soconusco, Chiapas en 2014. Se analizaron las acciones conjuntas relacionadas con la mejora de la comercialización de su producto. Se empleó la escala de construcción de vínculos relacionales para el trabajo colectivo integrada por los niveles de identificación, aportación, colaboración, cooperación y asociación. A través del análisis de redes sociales (ARS) se identificaron el número de relaciones, y los indicadores de densidad e índice de centralización por cada nivel. Los resultados indican una disminución considerable en las relaciones presentes (47, 24, 11, 6, 3) en orden ascendente de los niveles evaluados; a mayor nivel de relación, menor número de éstas. Las densidades más bajas se reportaron en los niveles de colaboración (1.6%), cooperación (0.09%) y asociación (0.07%). Se observa una fuerte desarticulación social atribuible principalmente a experiencias organizativas previas, individualismo, y visiones diferentes de la actividad productiva. Se observa un escenario de desconfianza y deficiente compromiso entre los miembros que influye negativamente en los emprendimientos colectivos. Se concluye que es necesario realizar acciones que promuevan una mayor articulación social, confianza y cultura organizacional entre los productores, previo o a la par de iniciativas de integación comercial.

Palabras clave: análisis de redes sociales; construcción de vínculos sociales; confianza; trabajo en conjunto

Introduction

The rambutan is a fruit crop of economic importance in the Soconusco, Chiapas region. Its incorporation is an alternative conversion and more profitable and attractive diversification on the main crops of cocoa and coffee in the area (Méndez et al., 2009). This has led to a significant increase in surface, which in recent years has led to a high production of fruit that cannot market properly, mainly due to poor existing marketing channels and ignorance of the fruit by a large segment of the population, which adversely affects the profitability of producers.

Lara (2008) reports that in the process orientation toward solving problems should be reciprocity and rely on trust, and that this will allow to work together to achieve common goals. In rural areas, there is a strong culture to the form of individual production due mainly to the prevailing mistrust between producers which limits the implementation of joint actions (Teja, 2010; Mamani, 2012), this favors a low link between farmers in the amount of resources and capabilities, resulting in fewer opportunities for development, because it implies a disjointed society that can hardly achieve common benefits (Pérez et al., 2011).

In societies there is a web of exchanges that can be a social network; them to achieve a degree of stability, possible to meet certain needs of the people involved through a series of connections that open up a horizon of possibilities that allow constitute a form of communication, organization and association based on reciprocity, common values and efforts that allow the generation of cooperation, commitment and trust (Carosio, 2009).

The social capital can be understood as the content of certain social relations that combine attitudes of trust with behaviors of reciprocity and cooperation (Lin, 2001; Durston, 2002), which provides greater benefits to those who possess compared to what could be achieved without this asset (Putnam, 1993); facilitating coordination, cooperation and generalized reciprocity towards the collective benefits (Coleman, 1990) and has been shown to be a key contributor to economic growth and sustainable development (Gómez et al., 2012). Their presence in a territory, leading to a cohesive social development, in which agents interact on the basis of shared ethical values and an efficient formal rules that underpin the development process (García-Valdecasas, 2011). The capital comes from belonging to social networks where trust relationships generate reciprocal obligations and at the same time encourage the consolidation of cooperation commitments (Herreros, 2012).

Rovere (1999 and 2004) states that networks are networks of people, where they connect or link people which defines networks as the language of links, where in the process of building networks there are different levels or depth link whose knowledge serves to organize and monitor the degree of consistency of a network based on present values flowing in relations given in five levels, each of which serves to support the following, these levels are: 1) recognition : it states that the other exists, as interlocutor, even as an adversary; present value: acceptance; 2) Knowledge: what the other does, what the other is; present value: interest; 3) Collaboration: assist sporadically present value: reciprocity; 4) cooperation: activities and knowledge sharing; present value: solidarity; and 5) association: support joint projects or initiatives which involves sharing resources; present value: trust. This process of building links poses aimed generating deep relationships of trust; the which are more dynamic to lead to collective action in positively influence the development and economic growth (Teilmann, 2012; Koutsou et al., 2014) since the essence of networks constitutes associativity (Rovere and Tamargo, 2005).

Through the analysis of social networks (ARS) is possible to analyze the ways in which individuals or organizations are connected or linked, in order to determine the overall structure of the network, their groups and the position of individuals or organizations singular in it, so that it deepens the social structures that underlie the f lows of knowledge or information, exchanges, or which are key to understanding the behavior of actors within each network power (Sanz, 2003) the performance of the network as a whole (Aguirre, 2011). The importance of studies to deepen the level of integration and social articulation through the analysis of social relations present among farmers is an important tool to analyze the influence these have on the functioning of collective groups and the scope and effectiveness of results, product performance of joint actions that contribute to improving common problems.

Based on the above, this research aimed to analyze the influence of the behavior of social relations between producers of rambutan to carry out joint actions that contribute to improving the marketing of production.

Materials and methods

The research was conducted in the Soconusco, Chiapas, a region in the municipalities of Tuxtla Chico, Cacahoatán, Metapa de Dominguez and Frontera Hidalgo during the months of june and july 2014. For the collection of information, applied a semistructured survey was developed by direct interview to the 22 producers that make up the group "Brotherhood". This integrated survey questions regarding age and education of the producer, and their years in activity, basic data production unit, its level of innovation and depth has social relationships, using the questions proposed by Zarazúa et al. (2012). Reference being categorizing Rovere scale by Mamani (2012). With the information gathered, it was developed a database that allowed the construction and calculation of indicators of networks using the methodology proposed by Rendón et al. (2007) that were centralization density and rate of input and output for each level UCINET 6.523® the programs being used (Borgatti et al., 2002) and Gephi 0.8.2® (Bastian et al., 2009).

The rate of adoption of innovations (IAI) and the rate of adoption of innovations by category (IAIC) were calculated being used the methodology developed by Muñoz et al. (2007). An analysis of hierarchical clustering using Euclidean distance squared and method of Agglomeration Ward (Pérez, 2004), the t test for equal means and chi square, a set of 25 variables related to attributes of the producer, the unit was performed production, dynamics of technological innovation and organizational background, in order to assess the degree of similarity between the producers in the group studied, using for this the statistical software SPSS 18®.

Results

The Table 1 shows the profile of the surveyed producers and their production units. The information indicates that the attributes that had a higher coefficient of variation correspond to the land surfaces, surface production rambutan and years devoted to productive activity. The years engaged in productive activity, indicating that producers have spent on average about 25% of its total age-related work this crop considering the average age of them. With respect to years of schooling, this group of producers has a high educational level, 76% have studies than high school level and exercise activities as teachers, merchants, professionals, bureaucrats, among others related to the service sector, allowing a diverse set producers in terms of economic activities.

In 72% of the producers, in the beginning the production of rambutan served as a complementary economic activity to their main economic activity. Over time the activity has had significant growth, where 64% mentioned that this part with 55-60% of its total revenue and is its main economic activity and the most important. In relation to infrastructure and basic for the production equipment, a relatively homogeneous group, which mainly include roads, warehouses, irrigation systems, transportation and electrical infrastructure, which are essential for the various cultural practices of the culture it was observed.

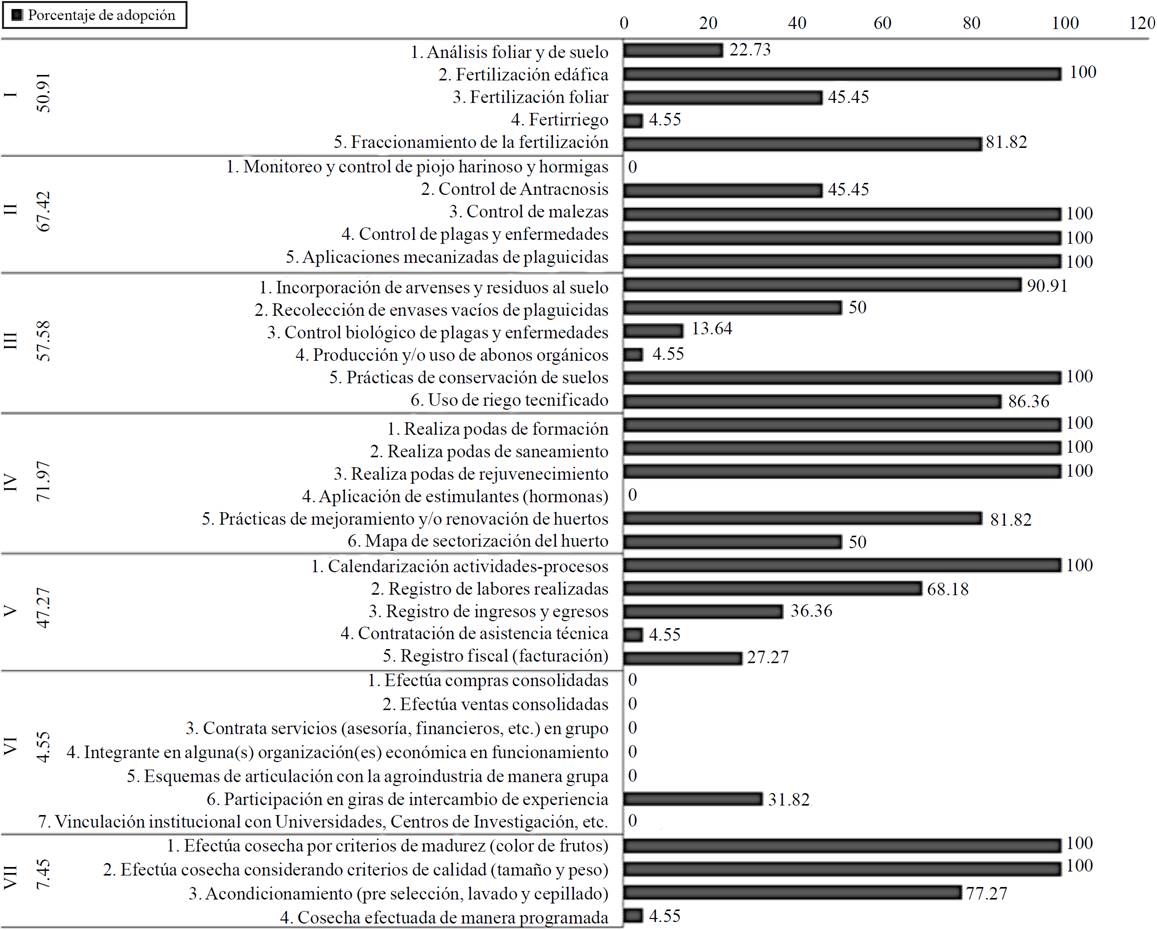

As for the dynamics of the adoption of this innovation among producers, Figure 1 indicates that the adoption of innovations is above 50% for most categories except for the category of management and organization (V and VI).

Despite the presence of an InAI of 52.86% within the production system rambutan, certain areas of necessary improvement of care that are limiting for the production and commercial activity not only in the case of producers studied but also applicable to a broad detected rambutan producer group present. These areas for improvement to address are: i) a high diversity of genetic material (selections and varieties) plantations, which generates heterogeneity in the quality of the fruit produced; ii) general lack of proper control and management of pests and diseases of importance, including the mealybug which is a quarantine pest that is a barrier to plant fruit for the export market; iii) deficient and inadequate in many cases performing cultural tasks, such as pruning, weed control and fertilization; most recurrent among small producers to contemplate the collection activity; iv) little to no renewal of orchards with commercial grade materials through re grafts or replanting; v) minimum performance of good harvest and postharvest work, especially in the upper area of the Soconusco, where the transport of fruit causes severe injuries that impair their commercial quality and affects a high percentage of fruit rejection balers; and vii) lack of quality standards governing the export market by a large number of smallholders. These limitations envisage a scenario feasible to carry out actions jointly by producers organized manner, enabling them to achieve more satisfactory results that benefit the sector collectively; this involves their participation and involvement in the management of innovations that contribute to further economic and social development of the sector.

In the category concerning the organizational situation, the result of adoption is low with a value of 5%, with the lowest levels to zero in this category innovations concerning the implementation of joint actions between producers such as: shopping and consolidated sales, hiring professional services and technical assistance, membership and active participations in one or several economic organizations that are currently running. This situation was ref lected among the producing members of the group analyzed in a downward trend in levels of integration for collective work as the level of articulation can be seen in Figure 2 is increased.

In levels identifies and provides cataloged by Mamani (2012) as superficial as many relationships is located, allowing indicate that activities that producers usually performed with peers were related to interest in joint action, such as test new products and share ideas and information. In a smaller proportion has been given the exchange of relevant information that a positive impact on their productive activity, such as recommendations of fertilization, performing certain cultural practices, and reference nurserymen with good genetic materials for planting new areas. Disarticulation existing high levels of deep collaboration, cooperation and partnership sets up a scenario where a f low limited prevails and scarce collective values of reciprocity, solidarity and confidence as shown by the density indicators (Table 2).

According to Burt (2000) the density indicator determines the bond strength between the links in the network and, in turn, it is an indicator that measures the degree of similarity of opinions, perceptions and common beliefs in a social group Williner et al. (2012). This relational behavior among producers studied favors a scenario of productive disunity mainly caused by the high prevailing mistrust between them, a condition that makes unfeasible the successful culmination of joint actions. Coleman (1990) mentions that a denser community is more likely to survive in the media that their bonds of trust, reciprocity and cooperation are greater.

Regarding centralization index, according to Williner et al. (2012) is an indicator of the network that evidence of an actor or group of actors controlling or influencing significantly over the rest of the set, in the centralization of entry into the first two levels identifies and provides refers to a group actors concentrating relations, which according to the opinion of the rest of the producers mentioned having outstanding features mainly related to their level of innovation, experience and willingness to work sharing, outstanding attributes that encourage them to strengthen their relationships for conducting activities collective. Mamani (2014) emphasizes that the reasons why the producers mentioned their peers as benchmarks, are strongly related to the qualities of character, dedication to work, order in its activities, in good spirits, sufficient expertise and high willingness to share knowledge and experiences.

For the identification of symmetry level present between producers rambutan studied, cluster analysis (clusters) hierarchical using euclidean distance and agglomeration method of Ward according to the methodology developed by Perez (2004) was performed, as shown in Figure 3.

The analysis allowed the identification of two sub groups from a total of 25 variables related attributes producer, unit production, innovation dynamics and attitudes, perceptions and behaviors of their peers in history of organizational work. The conglomerate I joined 9 producers and the conglomerate II remaining 13. To verify the difference between subgroups generated T-test comparison of means for quantitative variables and the chi-square test was performed for quantitative or categorical variables considering a probability of 10% (p< 0.1). Table 3 variables used for the separation of the generated subgroups are presented.

Dini (2010) mentions that the presence of symmetries in areas such as: size (unit production) capacity for economic investment, homogeneity in the final product quality, technological level, innovations, vision and common goals, healthy finances, willingness to participate and invest time and resources in the design and implementation of various group activities resulting from the membership of an organization, predict success in the implementation of joint actions and cooperation within an organization. The behavior in the dynamics of innovation may be a factor that can affect the functioning of the group and scope of agreements and commitments arising from collective action. Sebastian (2000) argues that in shaping cooperation networks, a limiting factor is the excessive heterogeneity of its members, where heterogeneity is related to asymmetries in the capabilities and contributions of partners; networks when it is excessive can lead to gradual loss of interest of participants with subsequent separation of some of them or dilution of the network.

With regard to factors related to behaviors and perceived attitudes of their peers in organizational history no significant difference is shown, which suggests widely producers report that their experiences of working together, the most prevalent behaviors in their peers are the breaches of agreements, financial mismanagement, violation of established norms, selfishness, opportunism, different views of business and prevalence of personal interests over collective which creates an environment of high distrust and the presence of a weak collective and organizational culture and low to nulls cultural partner for the collective work.

These results agree with those reported by FAO-SAGARPA (2014) in the study on the development of institutions of rural organizations in Mexico, where report the main reasons why organizations fail to operate are: 1) conflicts or disagreements internal; 2) weak leadership of the organization; 3) establishment of the organization with the sole purpose of managing public resources; 4) lack of partners by the organization; 5) mismanagement of financial resources; 6) ignorance and misinformation in many of the members on the activities taking place in the organization; 7) lack of involvement of members; 8) deficient formal rules and mechanisms for compliance and punishment; 9) unclear objectives for all member countries of the organization; and 10) weak commitment within the group. With respect to the latter, Sebastian (2000) mentions that the breach of commitments erodes the interest of the participants and destroys the possibilities offered a space for mutual benefit.

Rovere and Tamargo (2005) mention that by uniting individuals with very different interests and compositions for the purpose of forming collective work groups for achieving common objectives, is an opportunity to recognize the existence of conflict, dialogue and negotiate with others to produce agreements and council that result in actions aimed at achieving the achievements resulting from collective action.

Conclusions

It was observed that those in the group studied links rambutan producers, are more in the first two levels of identification and contribution. Values suggest that superficial relationships commitments, obligations and responsibilities shared between the producers are low to zero.

Networks deep relationships (collaborates, cooperates and associates) are disjointed and collective values of reciprocity, solidarity and trust are scarce, and a strong predominance towards individual work and a high presence of distrust, mainly attributable to the experiences and negative results in organizational history, which limits entrepreneurship and implementation of effective joint actions to help improve the marketing of their production.

Management innovations together and organized manner is a likely scenario that would allow further consolidation of deep bonds of trust and endowed collective farming that contributes to greater economic and social development of rambutan in the Soconusco Chiapas sector.

Literatura citada

Aguirre, J. L. 2011. Introducción al análisis de redes sociales. Documentos de trabajo del centro interdisciplinario para el estudio de políticas públicas (CIEPP). Buenos Aires, Argentina.82:1-59. [ Links ]

Bastian, M.; Heymann, S. and Jacomy, M. 2009. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. ICWSM. 8:361-362. [ Links ]

Borgatti, S. P.; Everett, M. G. and Freeman, L. C. 2002. Ucinet 6 for Windows: software for social network analysis. User’s guide. Harvard Analytic Technologies Inc. Massachusetts, USA. 47 p. [ Links ]

Burt, R. 2000. The network structure of social capital. Organizational behavior. 22:245-423. [ Links ]

Carosio, A. 2009. Redes socio productivas. Conceptos y experiencias en Venezuela. Revista Académica PROCOAS-AUGM. 1(1):4-20. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. 1990. Fondations of social theory. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. First edition. Massachusetts, USA. 321 p [ Links ]

Dini, M. 2010. Competitividad, redes de empresas y cooperación empresarial. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Santiago, Chile. Serie Gestión Pública. Núm. 72. 102 p. [ Links ]

Durston, J. 2002. El capital social campesino en la gestión del desarrollo rural: diadas, equipos, puentes y escaleras. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Santiago de Chile. 155 p. [ Links ]

SAGARPA-FAO. 2014. Estudio sobre el desarrollo institucional de las organizaciones rurales en México. Ciudad de México, México. 29 p. [ Links ]

García-Valdecasas, M. J. 2012. Una definición estructural de capital social. Redes: Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales. 20(6):132-160. [ Links ]

Gómez‐Limón, J.A.;Vera‐Toscano, E. and Garrido‐Fernández, F.E. 2014. Farmer’s contribution to agricultural social capital: evidence from Southern Spain. Rural Sociology. 79(3):380-410. [ Links ]

Herreros, V. F. 2002. ¿Son las relaciones sociales una fuente de recursos?: una definición del capital social. Papers.67:129-148 [ Links ]

Koutsou, S., M. Partalidou, y A. Ragkos. 2014. Young farmers’ social capital in Greece: Trust levels and collective actions. Journal of Rural Studies 34: 204 -211. [ Links ]

Lara, J. D. 2008. Redes de conocimiento y su desempeño. Estudios de caso en el noroeste de México. Editorial Plaza y Valdés. México, D. F. 250 p. [ Links ]

Lin, N. 2001. Social capital: social networks, civic engagement or trust? Hong Kong. J. Sociol. 2:1-38. [ Links ]

Mamani, O. C. 2012. Niveles de relacionamiento y balance estructural de la red de innovación de hule. Tesis doctoral. Centro de Investigaciones Económicas Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agricultura y Agroindustria Mundial- Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, México. 105 p. [ Links ]

Mamani, O. C. 2014. Redes sociales, instituciones y confianza de pequeños productores citricultores de la región huasteca veracruzana e hidalguense- México. Plaza y Valdés. México, D.F. 174p. [ Links ]

Méndez, L.; Sandoval, E. y Zamarripa, A. 2009. Establecimiento de frutales tropicales para diversificar plantaciones de café robusta. INIFAP- Centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Sur. Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa, Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, México. Folleto para Productores Núm. 13. 29 p. [ Links ]

Muñoz, R. M.; Aguilar, Á. J.; Rendón, M. R. and Altamirano, C. J. R. 2007. Análisis de la dinámica de innovación en cadenas agroalimentarias. CIESTAAM- PIIAI. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Chapingo, México. 82 p. [ Links ]

Pérez, L. C. 2004. Técnicas de análisis multivariantes de datos. Pearson Educación. Madrid, España. 672 p. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community USA. Editorial Simmons and Schuster. 1a. Edition. Nueva York, EUA. 384 p. [ Links ]

Pérez-Hernández, L. M.; Figueroa-Sandoval, B.; Díaz-Puente, J. M. and Almeraya- Quintero, S. X. 2011. Influencia de organizaciones en el desarrollo rural: caso de Salinas, San Luis Potosí. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2(4): 515-527. [ Links ]

Rendón, M. R. 2007. Identificación de actores clave para la gestión de la innovación: el uso de redes sociales. Serie: materiales de formación para las Agencias de Gestión de la Innovación. UACh- CIESTAAM. 50 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez- Modroño, P. 2012. Análisis relacional del capital social y el desarrollo de los sistemas productivos regionales. Redes-Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales. 23(9):260-290. [ Links ]

Rovere, R. M. 1999. Redes en salud: un nuevo paradigma para el abordaje de las organizaciones y la comunidad. Secretaría de Salud Pública. Rosario, Argentina. 113 p. [ Links ]

Rovere, R. M. 2004. Algunas sugerencias para el desarrollo futuro de la red de investigación en sistemas y servicios de salud en el Cono Sur de América Latina. Red de Investigación en Sistemas y Servicios de Salud en el Cono Sur. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 21 p. [ Links ]

Rovere, M. y Tamargo M. 2005. Redes y coaliciones o cómo ampliar el espacio de lo posible. Colección Gestión Social. Universidad de San Andrés. Argentina. 12 p. [ Links ]

Sanz, M. L. 2003. Análisis de redes sociales: o cómo representar las estructuras sociales subyacentes. Unidad de políticas comparadas. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid, España. Apuntes de ciencia y tecnología. Núm. 7. 10 p. [ Links ]

Sebastian, J. 2000. Las redes de cooperación como modelo organizativo y funcional para la I + D. Redes. 7(15): 97-111. [ Links ]

Teilmann, K. 2012. Measuring social capital accumulation in rural development. J. Rural Studies. 28(4):458-465. [ Links ]

Teja, G. R. 2010. Desarrollo de capacidades organizativas en el sistema producto cítricos para el impulso de la rentabilidad. Tesis Doctoral. Centro de Investigaciones Económicas Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y Agricultura Mundial- Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, México. 75 p. [ Links ]

Williner, A.; Sandoval, C.; Frías, M. y Pérez, J. 2012. Redes y pactos sociales territoriales en América Latina y el Caribe: sugerencias metodológicas para su construcción. CEPAL. Santiago de Chile. 67 p. [ Links ]

Zarazúa, J.; Almaguer-Vargas, G. y Rendón, R. 2012. Capital social. Caso red de innovación de maíz en Zamora, Michoacán, México. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural. 9(68):105-124. [ Links ]

Received: February 2016; Accepted: May 2016

texto em

texto em