Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 spe 15 Texcoco Jun./Ago. 2016

Articles

Farmer schools in Mexico: an analysis from social networks

1Universidad del Istmo-Campus Tehuantepec. Ciudad Universitaria s/n Barrio Santa Cruz, 4a Sección. Santo Domingo Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. C. P. 70780. (ortiz.bersain@colpos.mx).

2Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Montecillo. Carretera México-Texcoco, km 36.5. Montecillo, Estado de México, México. 56230. (ljs@colpos.mx).

3Universidad Autónoma Chapingo-Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM). (juliodiaz.jose@gmail.com).

Ownership and transfer of knowledge from producer to producer, is the beginning of farmer schools; in that sense, social capital is important in individual and collective relations. The methodology of farmer schools has been tested in rural communities to increase awareness among producers. The aim of this paper was to analyze knowledge flows of technology in the production of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) in a greenhouse, estimating parameters of social networks at the beginning of the farmer schools in 2010 and his term in 2011. They worked with producers small-scale rural in the state of Oaxaca who participated in the farmer schools for technology transfer. The sample selection was conducted by taking attendees producers and not attending farmer schools. After the process of farmer schools, relationships of input and output information technology increased by 28% and relationships between producers to have agreements or share resources increased participants in schools. In general, producers who participated in the farmer schools performed better communication relationships, better access to technology and improved production yields.

Keywords: agent of change; farmer schools; knowledge flows; social network analysis

La apropiación y trasmisión de conocimientos de productor a productor, es el principio de las escuelas de campo; en ese sentido, el capital social es importante en las relaciones individuales y colectivas. La metodología de las escuelas de campo ha sido probada en comunidades rurales para incrementar el conocimiento entre productores. El objetivo del presente artículo fue analizar los flujos de conocimientos de tecnología en la producción de jitomate (Lycopersicon esculentum) en invernadero, estimando parámetros de redes sociales al inicio de las escuelas de campo en 2010 y a su término en 2011. Se trabajó con productores de pequeña escala del medio rural en el estado de Oaxaca que participaron en las escuelas de campo para la transferencia de tecnología. La selección de la muestra fue dirigida tomando productores asistentes y no asistentes a las escuelas de campo. Después del proceso de las escuelas de campo, las relaciones de entrada y salida de información sobre tecnología aumentaron en 28% y las relaciones entre los productores para tener acuerdos o compartir recursos se incrementaron en los participantes en las escuelas. En general, productores que participaron en las escuelas de campo, obtuvieron mejores relaciones de comunicación, mejor accesos a la tecnología y mejoraron los rendimientos en la producción.

Palabras clave: agente de cambio; análisis de redes sociales; escuelas de campo; flujos de conocimientos

Introduction

The focus of farmer schools (EEC) was introduced in 1991 by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a way of introducing intensive knowledge in integrated pest management (MIP) in Asia management, and since then it has evolved to include a vast number of topics for the dissemination and exchange of knowledge in agriculture, using participatory methods that help farmers develop their analytical skills, critical thinking and creativity (Feder et al., 2004; Braun et al., 2006). Farmer schools, are formed by groups of farmers who meet weekly throughout the growing season of a crop, in order to share and enhance local knowledge, acquire new skills and find better strategies for handling new technologies (FAO, 2005).

The EEC emerged as a vision of extensionism of "bottom up" with emphasis on participatory learning, experience and reflective, which improves the ability of producers to solve their own problems (Larsen and Lilleør, 2014). The EEC has been implemented and adopted in different parts of the world (Friis-Hansen and Taylor, 2011; Duveskog et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2012) and Mexico (Cirilo, 2008; Gaytan, 2008). The results indicate that the EEC is an important training method that facilitates personal transformation, changes in roles and gender, as well as increasing productive economic indicators related to income and revenue for the producer.

The EEC has been implemented in rural communities to increase knowledge sharing between producers. According to Orozco (2008) farmer schools contributed significantly in the rate of adoption of technology to milpa interspersed with fruit trees (MIAF). The basic principle of farmer school is to contribute, through joint information and experience, to raise awareness for those who are producers and promoters in their community. These investigations reflect the importance of the EEC to disseminate knowledge, improve interpersonal relationships and trust of the actors, which can be reflected in productive results.

According to Larsen and Lilleør (2014) the results of the application of the EEC have been evaluated from two perspectives: the first has been based on the adoption of technologies, increasing yields, productivity and income; while the second has focused on empowerment results. However, the literature has not addressed how relationships between producers behave from participation in the EEC. These relationships of knowledge and information can be analyzed from the perspective of social networks.

The social networks explain how the diffusion of innovations is given, through their effects on the processes of social learning, joint assessment, social influence and collective action (Kohler et al., 2007; Monge et al., 2008; Spielman et al., 2010). However, networks are dynamic in nature and can be analyzed from a temporary approach (Diaz et al., 2013); i.e. analyze how relationships change over time; or they can be analyzed from the perspective of relationship level, i.e., from trust between individuals to interact. The latter approach associated with the test Simmel (1906) on the fact that human relations are restricted to what they know each other, and under the principle that know who it is the first condition for a deal with someone.

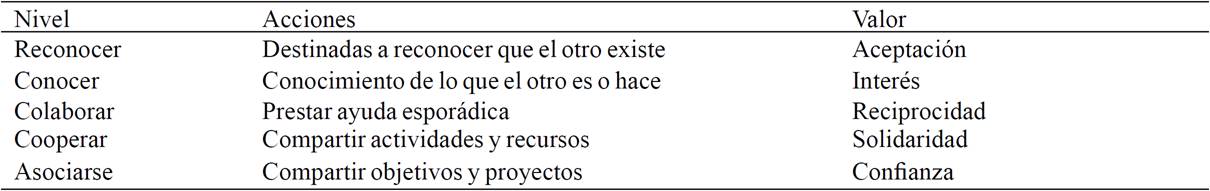

Under the approach levels of relationships, these links can be expressed through the following five levels (Rovere, 1999): i) level of recognition, which expresses the acceptance that the other exists; ii) level of knowledge, in which the other person as a pair or in this case as a producer is recognized as a valid interlocutor; iii) level of cooperation, for which work is part of a working relationship, is a spontaneous assistance, there are moments, facts, circumstances where collaboration mechanisms begin to structure a series of reciprocal links are verified, it begins to collaborate but mutual cooperation is expected; iv) cooperation, as a joint operation; these involves a more complex process because there is a common problem, therefore, there is a systematic sharing activities; and v) association, which deepens some form of contract or agreement that means sharing resources.

As shown, each level has to do with relationships between two or more people and the degree of acceptance and self-interest. The levels are ordered from the level of recognition, until the association. Each level supports the next; that is to say, is the basis for a stronger relationship. In general, the hypothesis that the importance of the relations of human capital associated with the technology and knowledge transfer methods for productivity, are engines for rural development impact is planted.

From a temporal analysis and levels of engagement, the objective of this article was to analyze the relationship of learning and cooperation on small producers of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) Of the communities of Santo Domingo Teojomulco and San Jacinto Tlacotepec, Oaxaca, They are participating in farmer schools. The results indicate that participation in the EEC promoted the spread of new technologies, technical relations and productivity increased.

Methodology

A selection of tomato producers was conducted in the municipalities of Santo Domingo and San Jacinto Tlacotepec, Teojomulco, Oaxaca, by a nonrandom sample. We worked with 18 greenhouses growing tomatoes and a questionnaire was applied to determine the flow of technological knowledge. The questionnaire was designed from five levels of association (Table 1) with emphasis on the dissemination of technological knowledge in the production of tomatoes in the greenhouse. This questionnaire was applied in two stages: 1) as a baseline, before the intervention of EEC; and 2) as the final line after the intervention in the EEC.

For information analysis methodology of social networks, which identified learning relations and cooperation for the production of tomatoes under greenhouse conditions applied. By analyzing social networks relationships or linkages they were identified, and indexes of centralization, dissemination and structure were calculated.

The information was collected to start the process of farmer schools in 2010 and finish it in 2011. With both estimates were possible estimates on changes in the relationships between tomato producers in the state of Oaxaca.

In networks mapping three important indicators were calculated: i) the centrality refers to nodes individually; ii) centralization as a property of the network as a whole; and iii) the structure, which refers to the function of certain actors and actors groups throughout the network (Rendon et al., 2007).

Results and discussion

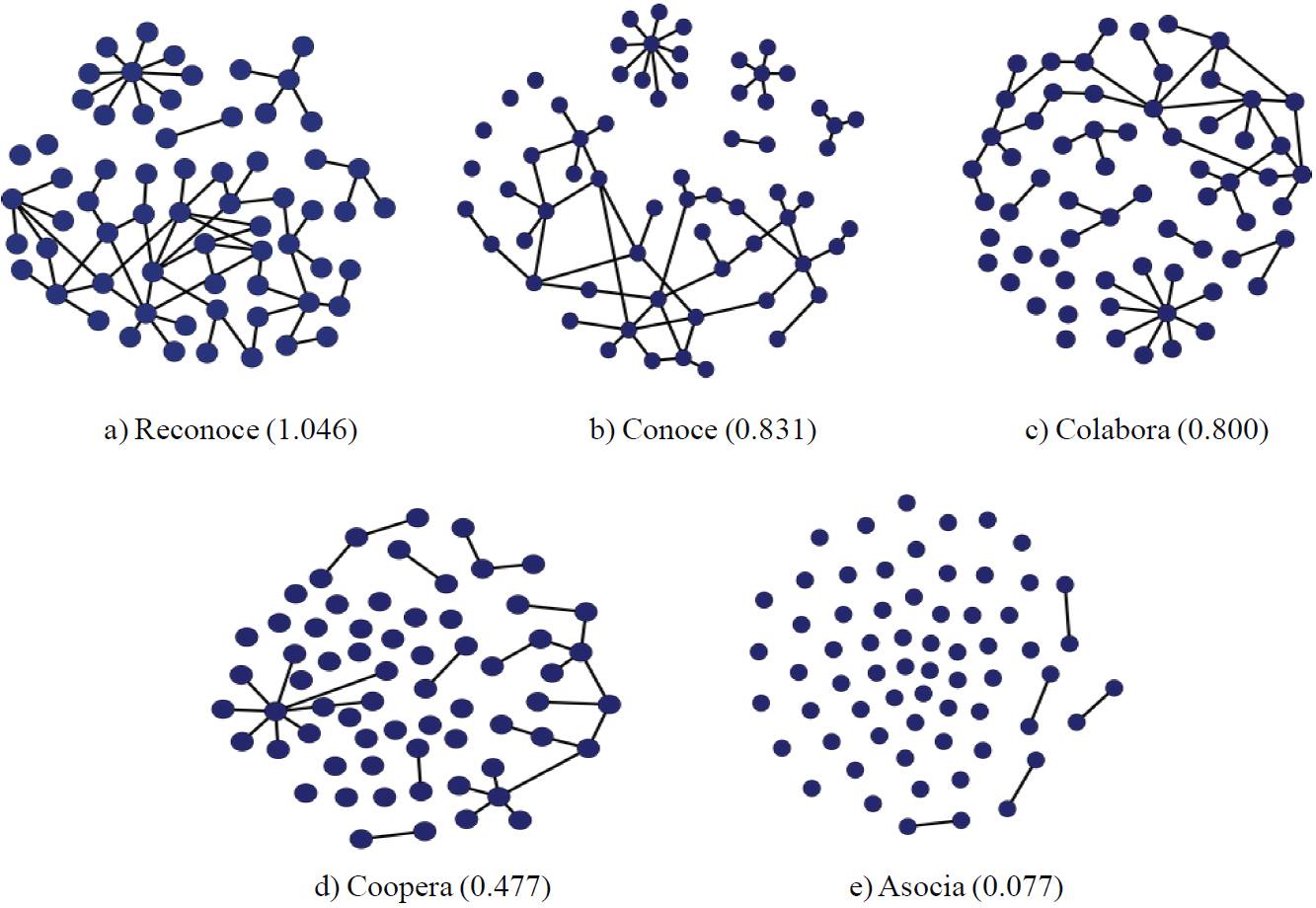

Analysis of information flows baseline

The first set of findings is related to the level analysis relationships producers, and was addressed in the context of the proposed initial farmer schools. First, the level recognizes the level of acceptance, where the producer acknowledges the existence of other producers in their environment, but no more than that, therefore, the average ratios of producers is greater than the other levels relationship (Figure 1a).

Second, know or interest level (Figure 1-b) few changes are observed in relation to the level recognizes, however, the average relationship is reduced, since it implies a knowledge of what other producers are or do. Third, the level works (Figure 1c) relations further diminished as it involves assisting or participating in any joint activity, although sporadically. Fourth, the level of relations cooperates average network falls more than half from the initial state to recognize (Figure 1d). Cooperation is important to build new levels of organization in humans, it is cooperating when you have problems in common and there is a process to address these problems more systematically. Therefore, at this level the relations between producers are scarce, since the affinity is implied of people, kinship, direct and indirect reciprocity, reputation and competition between groups (Nowak 2006).

Finally, at the associated level (Figure 1e), the formation of groups and links between producers is almost nil. In addition, here are shared resources and activity delves into contracts and agreements, the level of trust and network links to constrict dyadic relationships formed between 5 pairs of tomato producers. The level of partnership requires high levels of trust among peers, and even more between groups if they want to form organizations or companies.

Results streams of information after the process of farmer schools

After the implementation of farmer schools the same methodology was applied for the status guarding levels of relationship between producers. The total number of producers or actors or nodes of the network, after the process of farmer schools was 68 producers in both municipalities. Within this universe of producers, the producers of tomato, technicians, family, suppliers and other participating organizations of the baseline was identified.

In general, both the baseline and the results after the process of farmer schools, relations are reduced, i.e., when the bonds are stronger producers become more commitments, which are reciprocal and trustworthy. However, in the process after farmer schools, emphasis on seeking common interests, collective action and group work was given, which was reflected in each of the levels, the percentages to move to another were more consistent level compared to baseline. In the last level the existence of group work is appreciated, and a significant increase in the level of association with respect to the baseline (Figure 2).

When comparing between baseline and networks after participating in farmer schools, there are two things: first that at the most basic levels (recognizes and knows) the average of the ratios decreased, since the relationship in producers goes beyond the mere recognition; and second, from the level of collaboration relations they increased, indicating higher levels of cooperation.

At different levels of relationships analyzed, the producers face dilemmas. Vollan and Ostrom (2010) mention that individuals who adopt rules for cooperation, achieve levels of cooperation that increase over time as long as the network or group where the number of people with the vision to cooperate; however, also they point out that if there is a significant number of free riders cooperation levels will fall over time. Farmer schools prove to be an effective method for improving levels of cooperation both in intensity and magnitude.

Degree of input and output information after the process of farmer schools

At level it recognizes the input level is 27%; i.e. the group of producers receiving information technology in the production of greenhouse tomatoes have expressed regarding 27% of the 68 producers. Meanwhile, output in the degree of information technology, 7% of the producers referred to as actors with whom they have relationships in technology issues.

On the second level and third level known works, the entry of information technology remains at 24% and output of information knowledge was 8%. In the fourth level (cooperates) and fifth level (associates), the information input rate decreases by 11% from 4%. After the process of farmer schools producers were more likely to give information technology.

The level relations associates, are among the most important in the organization of tomato producers. To reach the level associates, producers had to go through the previous levels (recognizes, knows, collaborates and cooperates). In the analysis of the associated level, the following was observed: at baseline remained 13 relationships; after the process of farmer schools these relationships increased to 35, which means that producers after farmer schools, increased their relationships in more than 100%.

Overall indicators after the process of farmer schools, according to the levels of relationship showed improvement, especially in relationships and the level of entry information; that is, there were major producers connections in the network to find technical information for tomato production. Somehow each actor played an important position according to their degree of input and output information. The degree of information output increased slightly and the density was better.

Technical relations between producers under the baseline, were formed from training and technical assistance, and the poor relationship between producers; however, after the process of farmer schools, relations were raised according to the principle of a learning environment, practice, trust and reciprocity, which impacted the adoption of knowledge and the yields obtained in the production of tomatoes in greenhouse, as the average yields obtained at baseline was 5 to 7 kg/m2, while after the process of farmer schools was 12 kg/m2.

Conclusions

The principle of the methodology of farmer schools was crucial for producers to adopt technology and have a significant role in the networks of relationships flow of knowledge. According to the hypothesis, producers participating in farmer schools improve their relations, adopt new knowledge and improve yields in the production of tomatoes in the greenhouse.

From this study it is assumed that producers are becoming stronger commitments or relationships from the point of view of the levels of relationship: recognition, knowledge, cooperation, collaboration and partnership; the average relationship becomes weaker as demand for trust, solidarity, reciprocity, interest and acceptance increases, to establish a relationship of producer to producer. A further study is needed to understand the factors influencing changes in levels of relations, as well as the criteria to be taken for farmer schools serve as a means to enhance cooperation and partnership between producers.

Literatura citada

Braun, A.; Jiggins, J.; Röling, N.; van den Berg, H.; and Snijders, P. 2006. A global survey and review of farmer field school experiences. Report prepared for ILRI. Endelea. Wageningen, The Nethrelands. 91 p. [ Links ]

Orozco, C. S.; Jiménez, S. L.; Estrella, Ch. N.; Ramírez, V. B.; Peña, O. B. V.; Ramos S. Á. and Morales, G. M. 2008. Escuelas de campo y disponibilidad alimentaria en una región indígena de México. Estudios Sociales. 16(32):207-226. [ Links ]

Davis, K.; Nkonya, E.; Kato, E.; Mekonnen, D. A.; Odendo, M.; Miiro, R. and Nkuba, J. 2012. Impact of farmer field schools on agricultural productivity and poverty in East Africa. World Development. 40(2): 402-413. [ Links ]

Díaz-José, J.; Rendón-Medel, R.; Aguilar-Ávila, J. and Muñoz- Rodríguez, M. 2013. Análisis dinámico de redes en la difusión de innovaciones agrícolas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 4(7):1095-1102. [ Links ]

Duveskog, D.; Friis-Hansen, E. and Taylor, E. W. 2011. Farmer field schools in rural Kenya: a transformative learning experience. J. Dev. Stud. 47(10):1529-1544. [ Links ]

FAO. 2005. Escuelas de campo para la agricultores (ECAs) en el PESA- Nicaragua. Una experiencia participativa de extensión para contribuir a la seguridad alimentaria y nutrición en Nicaragua. Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación. Honduras. 27 p. [ Links ]

Feder, G.; Murgai, R. and Quizon, J. B. 2004. Sending farmers back to school: the impact of farmer field schools in Indonesia. Appl. Econ. Persp. Policy. 26(1):45-62. [ Links ]

López, G. J.; Jiménez, S. L.; León, M. A.; Figueroa, R. O. L.; Morales, G. M. and González, R. V. 2008. Escuelas de campo, para capacitación y divulgación con tecnologías sustentables en comunidades indígenas. Agric. Téc. Méx. 34(1):33-42. [ Links ]

Larsen, A. F. and Lilleør, H. B. 2014. Beyond the field: The impact of farmer field schools on food security and poverty alleviation. World Development . 64: 843-859. [ Links ]

Monge, M.; Hartwich, F. and Halgin, D. 2008. How Change Agents and Social Capital Influence the Adoption of Innovations among Small Farmers. Evidence from Social Networks in Rural Bolivia. International Food Policy Research Institute. Washington, D. C., USA. 76 p. [ Links ]

Nowak, M. A. 2006. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science. 314(5805):1560-1563. [ Links ]

Orozco, C. S. 2008. Escuelas de campo y adopción de tecnología en laderas. Tesis de Doctorado. Colegio de Postgraduados. Puebla, México. 217 p. [ Links ]

Rendón, M. R.; Aguilar, Á. J.; Muñoz, R. M. y Altamirano, C. J. R. 2007. Identificación de actores clave para la gestión de la innovación: el uso de redes sociales. Agencia para la gestión de la innovación. Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo (UACh)-CIESTAAM/PIIAI. Primera edición. México. 51 p. [ Links ]

Simmel, G. 1906. The sociology of secrecy and of secret societies. Am. J. Sociol. 11(4): 441-498. [ Links ]

Spielman, D. J.; Davis, K.; Negash, M. and Ayele, G. 2011. Rural innovation systems and networks: findings from a study of Ethiopian smallholders. Agriculture and human values. 28(2):195-212. [ Links ]

Vollan, B. and Ostrom, E. 2010. Cooperation and the Commons. Science. 330(6006):923-924. [ Links ]

Yorobe, J. M.; Rejesus, R. M. and Hammig, M. D. 2011. Insecticide use impacts of integrated pest management (IPM) Farmer Field Schools: evidence from onion farmers in the Philippines. Agric. Sys. 104(7):580-587. [ Links ]

Received: January 2016; Accepted: March 2016

texto em

texto em