Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 no.7 Texcoco Set./Nov. 2016

Articles

Quality assessment corn tortilla added with oatmeal (Avena sativa L.) nixtamalized

1Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. (isai_205@hotmail.com; ofeliabg@hotmail.com).

2Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo. 56130. El Batán, Texcoco, Estado de México. (n.palacios@cgiar.org).

3Campo Experimental Valle de México-INIFAP. (villasenor.hector@inifap.gob. mx, hortelano.rene@inifap.gob.mx).

The excessive intake of refined flour and soda is one of the factors by which the Mexican population today occupies the first places in overweight and obesity worldwide. The development and promotion of foods with better nutritional balance can help to reverse this trend, using processes and traditional food of Mexican culture, as is nixtamalization, not just from corn, but other grains with recognized nutritional properties. The objective of this research was to make tortillas mixtures nixtamalized corn flour (HMN) with nixtamalized flour oats (HAVN), perform their chemical composition analysis and evaluate their sensory quality. The HAVN was obtained from the variety Obsidiana and HMN was the brand MINSA® brands. The HAVN: HMN mixtures evaluated were 10:90, 20:80, 30:70 and 40:60% respectively. The quality of the tortilla is measured based on the diameter (cm), thickness (mm), the weight of the tortilla hot and cold (g), the rollability, the performance of the hot and cold tortilla and colorimetry. Additionally a compositional analysis was made tortillas. Sensory evaluation was performed using a test of overall acceptability and attributes, using hedonic scales. The found significant differences between the mixtures, for weight of the tortilla hot and cold, cold and light performance. The tortillas spiked with 40% HAVN had high content of protein and fiber, but less acceptability; while 10 and 20% had better acceptability, taste, texture and higher protein content compared to the HMN.

Keywords: acceptability; nixtamalized flour porridge; protein content; tortilla quality

El consumo excesivo de harinas refinadas y refrescos es uno de los factores por los cuales hoy la población mexicana ocupa los primeros lugares en sobrepeso y obesidad a nivel mundial. El desarrollo y promoción del consumo de alimentos con mejor balance nutricional puede contribuir a revertir esta tendencia, al utilizar procesos y alimentos tradicionales de la cultura mexicana, como lo es la nixtamalizacion, y no solo de maíz, sino de otros granos con propiedades nutricionales reconocidas. El objetivo de esta investigación fue elaborar tortillas de mezclas de harina de maíz nixtamalizado (HMN) con harina de avena nixtamalizada (HAVN), realizar su análisis bromatológico y evaluar su calidad sensorial. La HAVN se obtuvo de la variedad Obsidiana y la HMN fue de la marca MINSA®. Las mezclas evaluadas de HAVN:HMN fueron 10:90, 20:80, 30:70 y 40:60 %, respectivamente. La calidad de la tortilla se midió con base en el diámetro (cm), espesor (mm), el peso de tortilla caliente y fría (g), la rolabilidad, el rendimiento de la tortilla caliente y fría y la colorimetría. Adicionalmente se realizó un análisis bromatológico a las tortillas. La evaluación sensorial se realizó mediante una prueba de aceptabilidad global y por atributos, usando escalas hedónicas. Se encontraron diferencias significativas entre las mezclas, para peso de la tortilla caliente y fría, rendimiento de tortilla fría y luminosidad. Las tortillas adicionadas con 40% de HAVN presentaron altos contenidos de proteína y fibra, pero menos aceptabilidad; mientras las de 10 y 20% presentaron mejor aceptabilidad, sabor, textura y contenido mayor de proteína comparado con las de HMN.

Palabras clave: aceptabilidad; calidad de la tortilla; contenido de proteína; harina de avena nixtamalizada

Introduction

In Mexico overweight and obesity affects 71.3% of adults and 34% of infants and adolescents (Barquera et al, 2013). This among others, due to loss of balance between energy intake and energy expenditure. According to Denova et al. (2010) some of the risk factors associated with obesity, in the Mexican population, are excessive consumption of refined flour, soda and corn tortillas accompanied by foods rich in calories and fat. So one of the recommendations to prevent obesity and overweight is increasing consumption of whole grains and other high fiber grains (Kristensen et al, 2012; Barquera et al, 2013).

The worldwide consumption of oat (Avena sativa L.) is associated with a nutraceutical effect (Daou and Zhang, 2012); i.e., which has a favorable effect on the health of consumers by reducing low-density lipoprotein (associated with heart disease cholesterol), because of the soluble fiber grain (Tiwari and Cummins, 2011). In addition, the oat has higher protein content (Ortiz et al, 2013), compared to corn and wheat, which are the most consumed in Mexico. About 85% of oat proteins are globulins (Colyer and Luthe, 1984), which it has higher concentration of the essential amino acid lysine, which are of greater nutritional value. So that foods with added grain or oatmeal are an option to diversify food products and offer alternatives consumer consumption. Despite the aforementioned characteristics of oat, in our country, 90% of its use is as feed, and for human consumption is 2 kg per capita, while consumption of corn and wheat, as tortillas and bread is 78.5 and 38.3 kg per capita, respectively (CANIMOLT, 2013).

The process of nixtamalization makes the tortilla table have higher nutritional quality compared with the raw corn. This process involves a thermal-alkaline treatment which modifies the structure of proteins corn to make them more digestible, such that zein, which is a nutritionally poor protein reduces its solubility; while glutelin higher nutritional value, increased solubility and hence the availability of essential amino acids (Castillo et al., 2009). It also, promotes significant increases in the calcium content and because resistant starch gelatinization during partial processes: cooking and steeping corn (nixtamalization); nixtamalized grinding and cooking or frying tortillas. With the aim of developing new foods with better nutritional balance, it has investigated the impact of different grains nixtamalization other maize. Thus, Téllez and Arellano (2005) obtained the optimum parameters of nixtamalization to produce bean flour, Ríos and Nieves (2009) of amaranth, Garcia and Sandoval (2011) of oat and Morales (2015) of barley.

There is a need to promote products that promote the health of Mexican consumers, so nixtamalized grain oats can be a source of excellent nutritional quality protein, fiber, calcium and resistant starch. Thus, the objective of this research was to make tortillas mixtures nixtamalized corn flour (HMN) with whole meal flour nixtamalized oats (HAVN), perform their chemical composition analysis and evaluate their sensory quality to determine the optimal mix to make tortillas table.

Materials and methods

The oat grain used was obtained from the Obsidiana variety, released by program oats National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock (INIFAP), cultivated under rainfed conditions, in Chapingo State of Mexico, during the season spring-summer in 2011. The nixtamalization oat was performed, based on described by García and Sandoval (2011), in the presence of 0.49% lime, 10.4 min cooking at 90 °C, then 2.9 h rested dried at 50 °C for 48 h then milling was performed in a powdery Lasser 100 mark, for whole meal oats nixtamalized (HAVN). Corn nixtamalized flour (HMN) used was brand MINSA® brands. The mixtures HAVN:HMN, treatments with two replications were 10:90, 20:80, 30:70 and 40:60% respectively.

The variables were evaluated in the mass, water absorption (%) indicating the amount of water required per 100 g and then weight (g) was measured. The moisture was carried out in 3 g of sample in an oven, brand Lumistell HTP-42, at 103 °C until constant weight and mass yield was calculated on the basis described by Salinas and Vázquez (2006) and also they were determined the luminosity (L), hue angle (Hue) and chroma using a Hunter Lab mini Scan EX plus.

For the preparation of tortillas, flour is hydrated and it was determined by touch the optimum consistency of the dough was divided into portions of 20 g, were pressed and baked tortillas on a metal griddle to 230 °C for 90 s. To evaluate the tortilla quality, the diameter (cm) and thickness (mm) was measured by a digital vernier AutoTec mark; the weight of hot tortilla (g) was determined after completion of cooking and weight of cold tortilla (g) was measured half an hour after it; the percentage of moisture in the tortilla was determined similarly as in the mass; the rollability was determined once their cooking and after being heavy hot; an omelet was wound into a cylindrical pen and based on the degree of rupture was rated on a hedonic scale, 1= breaks all tortilla, 2= 3/4 is broken, 3= breaks 1/2, 4= breaks 1/4 and 5=not broken anything. The performance of the hot and cold tortilla was calculated based on the above by Cortés (2015).Additionally colorimetric variables, brightness, hue angle and chroma were evaluated.

The bromatological variables measured in the tortilla were: percentage of protein, which was assessed using the Kjeldahl method AACC 46-12 (1998), the crude fiber was determined in a previously defatted sample using the method 49-10 AACC (2009), which consisted of boiling the sample in sulfuric acid 1.25%, and thereafter sodium hydroxide 1.25%, the resulting residue was constant weight, 130 °C for 2 h and subsequently calcined at 600 °C for 30 min. The ash percentage was performed according to AACC method 08 01 (1995) by incineration in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 3 h. Quantification of calcium was carried out by the method 965.09 AACC (2008) in 1 g sample was dried for 24 h at 100 °C and subsequently calcined for 4 h at 500 °C and atomic absorption spectrophotometer set was used a cathode lamp at a wavelength of422.7 nm. Furthermore the resistant starch content tortilla was obtained based on the method Goñi et al. (1996), by hydrolysis with pepsin at pH 1.5, followed by the breaking of digestible starch with a-amylase, after removal of the products of hydrolysis by centrifugation, the indigestible fraction, the residue was dispersed in half alkaline hydrolyzed entirely with amyloglucosidase enzyme, determining the glucose released.

To carry out sensory evaluation test and overall acceptability acceptability attributes for tortillas of each mixture was performed. The quantitative affective tests were conducted, focusing on acceptance testing using hedonic scales.

For the assignment of treatments to experimental units stayed in a complete block design at random with a repetition of each treatment; as experimental unit tortillas were considered, the SAS statistical package (SAS Institute, 2002) was used and comparison of Tukey ≤ 0.05 were performed to indicate the differences between the analyzed mixtures additionally Pearson correlations were performed between sensory atributes and an analysis of main components with the properties measured in the sensory evaluation.

Results and discussion

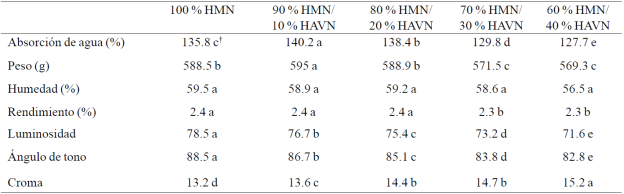

The significant differences between the masses mixtures of HMN and HAVN, for water absorption, weight, performance, lightness, chroma and hue angle were found; except for moisture of the masses, Table 1. The water absorption was 135.8% in HMN which is consistent with that reported by Flores et al. (2002), who reported values of 120 to 135% in different commercial flours. An increase in absorption and consequently its weight and yield of treatments with 10 and 20% was observed in HAVN; however, with 20 and 30%, these variables decreased, which may be due to the higher concentration of water-soluble polysaccharides capable of forming gums with little water. The moisture percentages ranged from 56.5 to 59.2% which is consistent with that reported by Gasca and Casas (2007). On the other hand, was observed a decrease in the brightness of the masses as the concentration HAVN increased, impacting the same way in the hue angle which is reported yellow in HMN and brown in the mixture with 40 % of HAVN which is consistent with that reported by Flores (2004). The brightness values for HMN match González and Hernández (2012) who reported values of 74 mass nixtamalized.

Table 1 Comparison of means features of physical and chemical mixtures of the masses of corn flour (HMN) nixtamalized flour and whole oats (HAVN).

†Valores con la misma letra dentro de filas no son estadísticamente iguales.

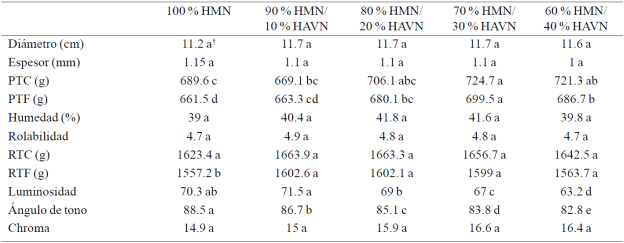

For quality variables significant differences tortilla weight of the hot and cold tortilla, cold tortilla performance, brightness and hue angle were observed; while the mixtures HMN and not differentially affected HAVN the diameter, thickness, moisture, rollability, performance hot tortilla and chroma. Based on the above, the addition of HAVN not change the dimensions of diameter and thickness of the tortilla, these values match so reported by González and Hernández (2012). Higher weight values for hot and cold tortilla were observed with the combination of 30 and 40% HAVN. On a commercial level this property represents an advantage because as many tortilla is sold with a lower percentage of raw material.

It is considered that 30% is the percentage HAVN adequate replacement for better weight of cold tortilla, the above is an advantage if marketed packaged tortilla and cold. The humidity ranged from 39.1 to 41.8% which depends on the use of raw materials spiked to HMN, which coincide with those reported by Gamero and Martínez (2010), who found similar values with mixtures of HMN and flour nixtamalized bean. Based on values greater than 4.8 of rollability, all mixtures of HMN/HAVN were classified with good factor for this feature, similar values found González and Hernández (2012).

The yields hot tortilla mixtures are similar to those found by Téllez and Arellano (2005) with mixtures of flour nixtamalized beans and HMN, in the case of performance cold tortilla Galicia (2009) reported values of1.4 kg, similar the treatments evaluated in this investigation. Incorporating HAVN affected the brightness of tortillas, as reflected in a decrease of 1.5, 3.4 and 7.1 units for mixtures of 20, 30 and 40%, respectively. As to, hue angle, the HMN tortillas were classified as yellow, however, with a gradual decrease trend is observed to be slightly brown with the addition with HAVN, Table 2.

Table 2 Comparison of means features of physical and chemical mixtures tortillas nixtamalized corn flour (HMN) nixtamalized flour and whole oats (HAVN).

†Valores con la misma letra dentro de filas no son estadísticamente iguales. PTC= peso de tortilla caliente; PTF= peso de tortilla fría; RTC= rendimiento de tortilla caliente; RTF= rendimiento de tortilla fría.

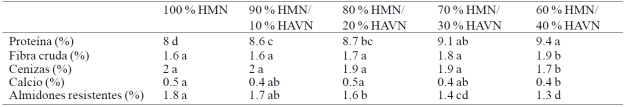

The significant difference for percentage of protein, crude fiber, ash, calcium and resistant starch, Table 3, the highest for protein for HMN values were spiked with 30 and 40% were found HAVN; for crude fiber the highest value was for the combination 60% HNM and 40% HAVN, these increases is because individually the HAVN is characterized by high percentages, greater than 15% (data not shown) which is consistent with that reported by Martinez et al. (2013) and Martinez et al. (2014), while the used HMN presented values lower than 9%. The percentage of resistant starch were higher for the HMN, which are comparable to those reported by Méndez et al. (2005); while by adding the HAVN its concentration decreased possibly due to low nixtamalization and soak times at which the oat grain subjected. The percentage of resistant starch for the HMN was higher than HAVN with values 0.7 and 0.2%, respectively, the latter value matches mentioned by Zamudio et al. (2015).

Table 3 Comparison of means of bromatological variables mixtures tortillas corn flour (HMN) and nixtamalized flour whole oats (HAVN).

†Valores con la misma letra dentro de filas no son estadísticamente iguales.

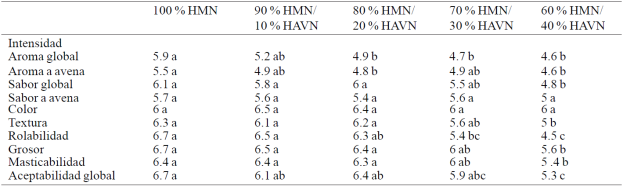

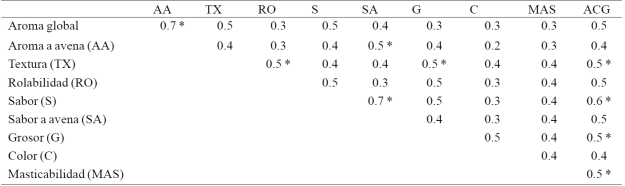

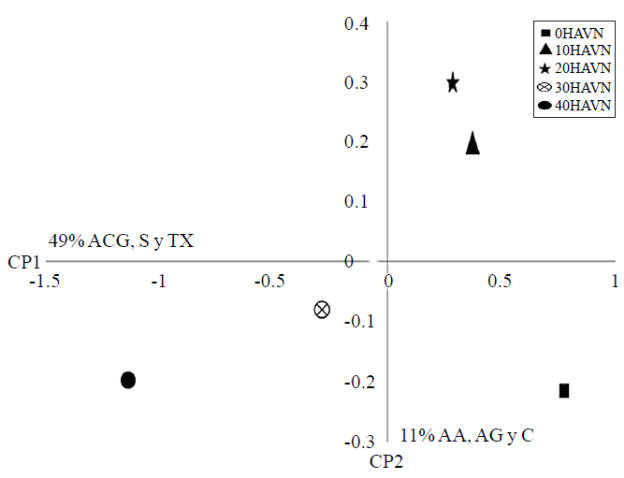

The significant differences for aroma, aroma oats, overall taste, texture, rollability, thickness, chewiness, and overall acceptability were observed; while there were none for oat flavor and color, Table 4. This indicates that the incorporation of HAVN was not detected by the panelists. The overall acceptability was correlated with texture, taste, thickness, chewiness, which indicates that these characteristics are crucial to the quality of the tortilla and same texture associated with rollability and thick tortilla, same behavior showed the flavor the taste of oatmeal, and oat scent was related to the overall aroma, Table 5. The variables greater contribution to the principal component 1 were: overall acceptability, flavor and texture; while overall flavor, aroma and color oats principal component 2, Figure 1. The treatments of 100% HMN and mixtures spiked with 10 and 20% of HAVN showed better overall acceptability characteristics, taste and texture largely affected tortilla ; reverse behavior presented by those made with 30 and 40% which are also associated with scented oatmeal (Figure 1).

Table 4 Comparison of means of sensory attributes of tortillas corn flour mixtures (HMN) and nixtamalized flour whole oats (HAVN).

Table 5 Pearson correlations between sensory attributes of tortillas corn flour mixtures (HMN) and nixtamalized flour

ACG= aceptabilidad global.

Figure 1 Two-dimensional distribution of tortilla corn flour mixtures (HMN) and nixtamalized flour whole oats (HAVN). 0HAVN= 100%HMN; 10HAVN= 90%HMN/10%HAVN; 20HAVN= 80%HMN/ 20%HAVN; 30HAVN= 70%HMN/30%HAVN; 40HAVN= 60%HMN/40%HAVN; ACG= overall acceptability; S= taste; TX= texture; AA= smell of oats; AG= overall flavor; C= color.

Conclusions

The tortillas made with 20% of HAVN and 80% of HMN presented tortilla quality and overall acceptability similar to 100% of cornmeal MINSA® brands, such treatment but decreased its brightness increased its percentage of protein. Adding 40% oat nixtamalized flour increased the protein content and fiber in tortillas however showed lower overall acceptability. Based on the above the use of whole grain oats, in the preparation of tortillas, favored the protein and fiber content so it can be recommended as a nutritional alternative food for the population.

Literatura citada

AACC.1995. Approved Methods. St. Paul, Minesota, U.S.A. [ Links ]

AACC. 1998. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. 9th Ed. The Association. Rev. St. Paul. Minn. 1020 p. [ Links ]

AACC. 2008. Approved Methods. St. Paul, Minesota, U.S.A. [ Links ]

AACC. 2009. Approved Methods. St. Paul, Minesota, U.S.A. [ Links ]

Barquera, S.; Campos, I. and Rivera, J.A. 2013. Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: the process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obesity reviews. 14:69-78. [ Links ]

CANIMOLT. 2013. Reporte estadístico al 2013. Disponible en: http://www.canimolt.org/revista-canimolt. [ Links ]

Castillo, V. K. C.; Ochoa, M. L. A.; Figueroa, C. J. D.; Delgado, L. E.; Gallegos, I. J. A. y Morales, C. J. 2009. Efecto de la concentración de hidróxido de calcio y tiempo de cocción del grano de maíz (Zea mays L.) nixtamalizado, sobre las características fisicoquímicas y reológicas del nixtamal. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 59(4):425-432. [ Links ]

Colyer, T. E. and Luthe, D. S. 1984. Quantitation of oat globulin by radioimmunoassay. Plant Physiol. 74(2):455-456. [ Links ]

Cortés, S. I. 2015. Contenido de almidón resistente, proteína y fibra en tortillas de maíz adicionadas con harina de Avena (Avena sativa L.) nixtamalizada. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 79 p. [ Links ]

Daou, C. and Zhang, H. 2012. Oatbeta-glucan: its role in health promotion and prevention of diseases. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 11:355-365. [ Links ]

Denova, G. E.; Castañón, S.; Talavera, J. O.; Gallegos, C. K.; Flores, M.; Dosamantes, C. D. and Salmerón, J. 2010. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in an urban Mexican population. The J. Nutr. 110:1-9. [ Links ]

Flores, F. R. 2004. Efecto de la incorporación de fibra dietética de diferentes fuentes sobre propiedades de textura y sensoriales en tortillas de maíz (Zea mays L.). Tesis de maestría, Centro de investigación en ciencia aplicada y tecnología avanzada. Querétaro, México. 85 p. [ Links ]

Flores, F. R.; Martínez, B. F.; Salinas, M.Y. y Ríos, E. 2002. Caracterización de harinas comerciales de maíz nixtamalizado. Agrociencia. 36:557-567. [ Links ]

Galicia, G. C. F. 2009. Efecto de fecha de siembra sobre la calidad comercial del grano de maíz y sus tortillas. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 84 p. [ Links ]

Gamero, P. J. L y Martínez, V. A. 2010. Elaboración y evaluación de seis productos enriquecidos con harina de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) nixtamalizado para consumo humano. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 84 p. [ Links ]

García, M. G. y Sandoval, D.A. 2011. Optimización de la nixtamalización de avena (Avena sativa L.) para obtener harina de avena nixtamalizada (HAVN) y su aplicación en pastas alimenticias. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 86 p. [ Links ]

Gasca, M. J. C. and Casas, A. N. B. 2007. Addition of nixtamalized corn flour to fresh nixtamalized corn masa. Effect on the textural properties of masa and tortilla. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 6:317-328. [ Links ]

Goñi, I.; Garcia, D. L.; Mañas, E. and Saura, C. F. 1996. Analysis of resistant starch: a method for foods and food products. Food chemistry. 56:445-449. [ Links ]

González, R. S. y Hernández, P. E. 2012. Efecto en la calidad de las tortillas de mesa usando como aditivo harina de amaranto (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) nixtamalizado. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. 96 p. [ Links ]

Kristensen, M.; Toubro, S.; Jensen, M. G.; Ross, A. B.; Riboldi, G.; Petronio, M.; Bugel, S.; Tetens, I. and Astrup, A. 2012. Whole grain compared with refined wheat decreases the percentage of body fat following a 12-week, energy-restricted dietary intervention inpostmenopausal women. The J. Nutr. 142:710-716. [ Links ]

Martínez, C. E.; Villaseñor, M. H. E.; Hortelano, S. R. R.; y Rodríguez, G. Ma. F. 2013. Evaluación de características físicas y contenido de proteína en el grano de genotipos de avena (Avena Sativa L.). Ciencia y Tecnol. Agrop. Mex. 1:39-45. [ Links ]

Martínez, C. E.; Villaseñor, M. H. E.; Hortelano, S. R. R.; Rodríguez, G. Ma. F.; Espitia, R. E. y Sosa, M. E. 2014. Caracterización de la calidad física y bioquímica del grano de genotipos de avena (Avena sativa L.) en México. Folleto técnico Núm. 63. INIFAP-CIRCE-CEVAMEX. 24 p. [ Links ]

Méndez, M. G.; Solorza, F. J.; Velázquez, del V. M; Gómez, M. N.; Paredes, L. O. y Bello, P. L. A. 2005. Composición química y caracterización calorimétrica de híbridos y variedades de maíz cultivadas en México. Agrociencia. 39:267-274. [ Links ]

Morales, L. G. 2015. Optimización de la nixtamalización de cebada maltera (Hordeum vulgare L.) y su aplicación en galleta integral dulce. Tesis profesional del Departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. p. 87. [ Links ]

Ortiz, R. F.; Villanueva, F. I.; Oomah, B. D.; Lares, A. I.; Proal, N. J. B. y Návar, Ch. J. J. 2013. Avenantramidas y componentes nutricionales de cuatro variedades mexicanas de avena (Avena sativa L.). Agrociencia. 47:225-232. [ Links ]

Ríos, B. M. y Nieves, G. R. 2009. Optimización de la nixtamalización de amaranto (Amaranthus hypocondriacus) para obtener harina y tortillas enriquecidas. Tesis profesional de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. 68 p. [ Links ]

Salinas, M. Y. y Vázquez, C. G. 2006. Metodologías de análisis de la calidad nixtamalera-tortillera en maíz. INIFAP. Folleto técnico Núm. 24. 98 p. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Institute. 2002. SAS user's guide. Statistics. Version 8. SAS Inst., Cary, NC. USA. Quality, and elemental removal. J. Environ. Qual. 19:749-756. [ Links ]

Téllez, T. P. y Arellano, S. V. A. 2005. Optimización de nixtamalización de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) y desarrollo de un nuevo producto alimenticio. Tesis profesional del departamento de Ingeniería Agroindustrial de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 75 p. [ Links ]

Tiwari, U. and Cummins, E. 2011. Meta-analysis of the effect of beta-glucan intake on blood cholesterol and glucose levels. Nutrition 27:1008-1016. [ Links ]

Zamudio, F. P. B.; Tirado, G. J.M.; Monter, M. J. G.; Aparicio, S. A.; Torruco, U. J. G. , Salgado, D. R. y Bello, P. L. A. 2015. Digestibilidad in vitro y propiedades térmicas, morfológicas y funcionales de harinas y almidones de avenas de diferentes variedades. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 14:81-97. [ Links ]

Received: June 2016; Accepted: August 2016

texto em

texto em