Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 no.7 Texcoco sep./nov. 2016

Articles

Profitability and competitiveness walnut crop in Sierra Nevada-Puebla

1Colegio de Posgraduados- Campus Puebla. Carretera Federal México-Puebla. km 125.5 Momoxpan, San Pedro Cholula, C. P. 72760. Teléfonos: 222 285 14 42. Puebla, México. (naxeailuna@yahoo.com; seresco@colpos.mx).

The state of Puebla is the second largest producer of walnuts (Juglans regia L.) in Mexico, emblematic fruit of traditional poblano-mexican dish: "chili in walnut sauce." The production of walnuts is part of the reproductive strategy of rural households in the region Sierra Nevada state of Puebla, main producing area and consuming fresh walnuts in Mexico. The aim of the study was to analyze the profitability and competitiveness of production in the traditional system, which has remained for about 300 years. The study was performed using matrix analysis methodology policy (MAP) with information obtained from 2011 to 2013, through questionnaires applied to 100 producers of walnuts, complemented by in-depth interviews to "representative" producers corn intercropping systems with fruit (MIAF) and orchard. The results indicated that the orchard system is more profitable and competitive than MIAF system at private prices, however at affordable prices MIAF system profitability was negative. Both production systems showed low economic competitiveness.

Keywords: Juglans regia L.; MIAF production system; production system orchard

El estado de Puebla es el segundo productor de nuez de Castilla (Juglans regia L.) en México, fruto emblemático del platillo tradicional poblano-mexicano: "chile en nogada". La producción de nuez de Castilla forma parte de la estrategia de reproducción de los hogares rurales de la región Sierra Nevada del Estado de Puebla, principal zona productora y consumidora de nuez de Castilla en fresco en México. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la rentabilidad económica y la competitividad de la producción en el sistema tradicional, el cual se ha mantenido por aproximadamente 300 años. El estudio se realizó usando la metodología matriz de análisis de política (MAP) con información obtenida entre los años 2011 a 2013, a través de cuestionarios aplicados a 100 productores de nuez de Castilla, complementada con entrevistas a profundidad a productores "representativos" de los sistemas maíz intercalado con frutales (MIAF) y en Huerto. Los resultados señalaron que el sistema Huerto es más rentable y competitivo que el sistema MIAF a precios privados, no obstante a precios económicos la rentabilidad del sistema MIAF resultó negativa. Ambos sistemas de producción mostraron baja competitividad económica.

Palabras clave: Juglans regia L.; sistema productivo MIAF; sistema productivo huerto

Introduction

The Sierra Nevada region is considered by producers and consumers of walnuts state of Puebla, the state's largest producing region. Such recognition due to the quality of the fruit (valued for its size and flavor) and volume of production. Characteristics associated with the soil and climatic conditions of the region: clay soil, temperate climate and average annual rainfall of 900 mm, in relief between 2300 and 2850 masl (INEGI, 2011). Conditions that have allowed great adaptability and crop yields important "under rainfed conditions" until 10 years ago. The climatic characteristics of the region Sierra Nevada, temperatures greater than 1.1 °C and under at 38 °C coincide with the conditions for the reproduction of the species Juglans regia L. suggested by Lemus (2010).

Production systems walnut identified in the region Sierra Nevada state of Puebla are traditional production systems, which are defined as traditional production systems those systems under various crops in time and space, which it allows producers to maximize production safety, even with little use of technology (Altieri and Nicholls, 2000): intercropped with maize, metepancles (Figure 1). The nut is consumed as fresh fruit to prepare "chilis in walnut sauce," the representative of the poblano-Mexican cuisine dish (Camacho et al, 2000; Luna et al., 2013).

The profitability of production of walnuts in orchard of high density -estimate in an orchard with an area of 5 ha, with 856 plants- calculated by Camacho et al. (2000), it was 30%. However, no evidence has been found of estimating the profitability of nut production in traditional system, which is the system in which small farmers keep growing walnuts in the region. The yields indicated by Camacho et al. (2000) 0.8 t ha-1 in an orchard of 7 years old and 1.4 t ha-1 in an orchard with older trees 15 years old are similar to those reported by Luna et al. (2013) 2 t ha1.

Figure 1 System Metepancle production. (Santa María Texmelucan, Santa Rita Tlahuapan, Puebla, 2013).

Worldwide, the fruit is eaten dehydrated. The main producing countries exporters are: China, the United States, France and Chili, among others, (USDA, 2011). From 2010 imports of walnuts (Juglans regia L.) californian and chilian are increasing, according to USDA-NASS (2013); with the possibility that displace domestic production in the regional market (which includes the main consumer states: Puebla, State of Mexico, Mexico City and Tlaxcala). Given the need to compete in the local market with imports of dehydrated walnut californian and recently chilian, it is important to measure the profitability and competitiveness of the production of walnuts, to facilitate consolidation in the regional market.

The discussion focuses on the scale in the confusion of the definition to be applied in different areas. In this sense, there is a discussion of the definition of competitiveness of a country. Macroeconomic theory suggests at least two definitions: 1) the growth rate of productivity is the ultimate measure of competitiveness, as a higher rate of productivity will sustain higher wages and higher rates of return on invested capital; and 2) the competitiveness of a country is the ability to make its products participate in the international market, which could mean in terms of policy, freeze wages and devalue the currency to make cheaper products from a country in the international market and therefore more competitive (Romo and Musik, 2005).

The third definition proposes that competitiveness is not an end but a complex process, a possible behavior from certain particular characteristics of the company constantly changing. And not vice versa, that competitive behavior is a result of positioning the company in the market Álvarez (2003). In this framework, analyzes have been made at company level, production system, industry, city, region and country. One of the methods used to measure competitiveness in the industry is the revealed comparative advantage. The method is based on the neoclassical theory that points to the strength and intensity of factors: land, labor and capital as factors of competitiveness in traditional industries such as footwear Morales and Rendón (2000)); Rendón and Morales (2001). Because competitiveness cannot be measured directly, indicators measuring the change in the absolute share of a city or an industry, for example, the gross value of national or industrial production in a period or year are used, or change in the indicator decide to use (Kresl and Singh, 1999).

The studies from the cultural perspective have been mixed, especially since the 90s; have been studied foodstuffs considered on the network or value chain to which they belong, to understand why they are consumed, i.e., as these processes and economic patterns by cultural systems are built, because from the perspective of cultural economy means to market relations as a cultural phenomenon (Zader, 2012). In this context, these approaches allow explore other perspectives with which to understand local processes, such as the permanence of walnuts, as local product on the market, which are not necessarily explained by its competitiveness based on the "price" or "international quality standards", but local cultural criteria, as they can be, natural product with "taste, tradition, and support of the local", among others.

The most widely used method for measuring competitiveness in agricultural production systems is the matrix of policy analysis (MAP), based on neoclassical theory, through which private profitability (for the producer) and the economic is measured (the cost opportunity to produce or import the product internally) (Magaña et al., 2002; Lara et al., 2003; Barrera et al., 2011). Methodology measuring production efficiency, the effect of exchange rate policy and subsidies on competitiveness of the production system.

The aim of this study was to estimate the economic profitability of traditional production systems walnut and estimate the competitiveness of nut production fresh with its californian counterpart, they both converge in the local-regional market. It is intended that this comparison technical contribution to the producers of the Sierra Nevada region, enabling them to better decision-making production and trade, given the recent local product competition with substitutes and the like, domestic and imported items. The hypothesis is that the system of traditional walnut production is profitable and competitive (Figure 1).

Materials and methods

The analysis of profitability and competitiveness was based on the methodology designed by Monke and Pearson (1989) of the University of Arizona and Stanford, respectively, called Policy Analysis Matrix (MAP). The MAP is a scheme of analysis is complemented by analysis methodology investment income and development Institute of the World Bank, Lara et al. (2003). The methodology measures the comparative advantage of a productive activity. It aims to measure efficiency in regional production systems and the effects of trade liberalization. The method is based on a system of double-entry accounting, which allows to demonstrate the effects of policies on profitability and production costs. The response to a product or input prices and the effects of a quantitative restriction on foreign trade and changes in the real exchange rate and balance. With information flows revenues, costs and profits to private and economic production systems are constructed prices, based on direct information from the different stages of the production chain. This profitability indicators, protection and subsidy are estimated.

The private prices are market prices. Competitiveness refers to the profit earned by producers (private). This is measured in the MAP with the indicator "private cost ratio" (RCP). Measured as the ratio between the cost of internal factors of production and added value, both valued at market prices. The decision rule is: if RCP < 1, the product is competitive (profitable); if RCP > 1 is not competitive, so that the producer is receiving windfall that is the reward to the management of the producer; if RCP= 1, the producer is not receiving windfalls, you get enough income to pay for the factors of production, including labor and capital.

Corporate earnings measure efficiency and comparative advantages, are calculated using the ratio of cost of internal resources (RCI). It is the ratio between the cost of internal factors at efficiency prices (unsubsidized) and economic value added; ie the import parity price, product, less inputs, both socially valued prices. If the value of the RCI is between zero and one, the product shows comparative advantage because the value of internal factors used is less than the value of the foreign exchange earned or saved. If the RCI> 1, the product has no comparative advantage as the value of domestic remedies exceeds that of the foreign exchange earned or saved, if the RCI <1, the product has no comparative advantages, because it represents a waste of currency production.

The methodology of the construction of matrices of technical coefficients vector of market prices and affordability, constructed from information obtained from production systems, the price of the product and inputs in the domestic market and internationally. To feed matrices were made structured interviews to three wholesalers regional marketers the municipality of San Nicolas of the Ranchos, three wholesale traders in the municipality of San Rafael Ixtapalucan (top traders in the region Sierra Nevada), two retail traders (canastera) of San Nicolás of the Ranchos and a marketer to restaurants in the city of Puebla. The semi-structured interviews were made to local markets traders Puebla, Atlixco, San Pedro Cholula and restaurants in the city of Puebla; Central supply Mexico and Central City Tlaxcala to meet the marketing channels and prices walnuts. The depth interviews with four producers in traditional MIAF system and four producers were made orchard. The questions producers were of four types: 1) cultivation tasks carried out during the year, quantities and costs of inputs and labor used during the year; 2) tasks performed to the product (post-harvest), quantities and costs, raw materials and labor used; 3) marketing channels and marketing expenses; and 4) use of products and sub-products, land rent and best alternative use of the land.

The minimum attractive rates of return on investment considered to update the private and economic assumptions were: TIIE at 91-day plus a premium equivalent to domestic inflation history (9.25%), as the cost of money in the country. The libor rate plus a premium equal to the rate of domestic inflation history (5.23%), to represent the cost of money at an international level, respectively. In the array power at prices of economic efficiency water subsidy of 50% it was assumed, as marketer's water use drinking water. It was considered that the best alternative land use is the production of flower cloud with two cuts a year (May, November). It estimated a production of2 400 rolls per year, sold at $16.22 pesos each roll, totaled $38 928.00 pesos a year, in cycles of four months in temporary, with a profit of $11 678.00 pesos.

At the cost of water payment it was considered by services and mechanized work, and because no electricity is used in the production process, harvest or post-harvest, no depreciation of machinery and equipment, and energy use was calculated electric and diesel, or interest rates and insurance payment. The competitiveness analysis was made considering the price of fresh walnut Californian shell, at CIF prices over import taxes, insurance and freight passing through Laredo to reach Central of Supplies Mexico and the average exchange rate for sale of 2012 (TC= 12.42).

Results and discussion

Production systems walnut identified in the region Sierra Nevada-Puebla, there were three, which are differentiated by the use, destination, place and degree of knowledge of the market by the producer. The system backyard or lot in which most of the production is for own consumption. The cornfields interleaved with fruit trees (MIAF) and the orchard in smallholdings.

The main system in the region Sierra Nevada is "backyard" which represents over 70% of total 2 900 production units (UP) identified. The corn intercropping with fruit trees (MIAF) system represents 68% of the 900 UP with at least 5 walnut trees in production. This system has different arrangements: walnut trees on edge (with maize, beans, squash, or other, with grain or alfalfa) and walnut trees interspersed with other fruit such as peach (Prunus persica), apple (Malus domestica), plum (Prunus domestica), pear (Pyrus communis L.), apricot (Prunus armeniaca), walnut (Juglans regia L.), hawthorn (Crataeguspubescens) and wild cherry (Prunus serotina), as noted by Mendoza et al. (2010). All arrangements reflect income strategies, parcel size, tastes of producers and end-market knowledge. The third is an orchard in smallholdings (maximum of 4 ha, 80% is less than 1 ha), the system represents 6% of production systems and is mainly destined for local and regional market.

The average yield estimated for tree 30 years in the region during the harvest 2011 was 1.25 thousand per tree in storm conditions (15.6 kg/tree). However, examples of yields recorded in the 2011 harvest are proof that performance depends on a combination of factors such as: characteristics of micro climate, crop management by the grower and producer awareness about growing as nutrition root, water requirements, soil slope, soil type, varieties of walnuts, and knowledge of the final market. For example, a tree 30 years old with a height of10.5 m in solar was 4.33 thousand (54.12 kg), another tree of the same age with a height of 7.9 m in MIAF system was 1.06 thousand (13.25 kg). Meanwhile, a tree 80 years old with 9.2 m high in solar, was 1.98 thousand (24.75 kg) and another tree 80 years old with a height of 7.9 m in MIAF system was 5.6 thousand (70 kg).

The local market walnuts. The market structure walnut of the Sierra Nevada region is represented by many small producers, small local and regional retailers and many small consumers. Marketing channels used are: direct sales (30%) and intermediate (66%), the rest occurs only for self-consumption (4%). Sales intermediary is given in two ways: purchase thousand home of producer and purchase of walnut tree, before flowering or fruiting. Marketers are from the study region and sell between 8 and 15 thousand a day. The direct sales channel is also given in two ways: in squares and local markets and cambaceo or door to door in the main urban centers producing region near municipalities.

The marketing channel used by the producer depends on the volume of production harvested, their principal occupation, their market access and the level of market knowledge. The main target market of fresh walnut is recorded during the season chili in walnut sauce, in the local markets of the city of Puebla, followed by local markets in the State of Mexico and the main streets of the city of Tlaxcala. Few traditional marketers, distinguished by families with three generations devoted to trade, who are known in the localities and producers, enjoying a good status to be considered economically solvent and market expert's walnut.

Most experienced marketers belong to the municipality of San Nicolas of the Ranchos, who understood the needs of end consumers and restaurateurs and began selling fresh clean nut in the city of Puebla. For 2 years walnut longer it offered packaged and labeled. Recently marketers the municipality of Santa Rita Tlahuapán, have begun selling fresh walnut clean for chilis in walnut sauce, mainly in local markets of San Martín, in the Market of the Merced Mexico City, in the streets of the State of Mexico and restaurants in Mexico City.

The marketers of San Nicolas of the Ranchos have established trade relations based on solidarity and trust with producers in other regions, both the State of Puebla, as the State of Mexico and Oaxaca. While marketers the municipality of Santa Rita Tlahuapán have established business relations with producers and marketers of the State of Mexico, based on relations of solidarity, trust and cronyism. With whom reciprocity is a constant, because the fruit ripening began in the backyards and orchard s of the State of Mexico in mid-July and ends in late August; and since the season of "chilis in walnut sauce" in Mexico City ends until 15 September, and the harvest of walnuts in the State of Puebla end until mid-September, then, reciprocity between traders is possible, as both parties agree to deliver their goods, own or achieved, to ensure the merchandise marketer and attention to its customers throughout the season "chilis in walnut sauce."

Profitability and competitiveness of two production systems

The MIAF system (intercropping maize-walnut) of temporary. The 68% of the area planted with walnut system is in production intercropped with maize in a smaller area half a hectare. But the purpose of analysis the following structure was considered: one hectare with five rows of walnut trees and corn intercropping to 10 m from walnut. Of which are 50 walnut trees ha-1 and 75 rows of corn every 80 cm. Every 75 cm there are 3 corn plants, totaling 30 000 plants ha-1 approximately.

The walnut harvest season is from late July to early September. The performance data were obtained from a farm in MIAF system located in the town of Santa María Nepopualco, municipality Huejotzingo, located at coordinates 19.15718" north latitude 98.48012" west ± 3", at a height of2 524 m with trees from 3.3 to 4.5 m high of 30 years old. The performance was measured by counting the number of small, medium and large fruits harvested in 2011 in a single cut. An average yield was obtained of 1.124 thousands per tree (equivalent to 14.05 kg shelled walnut tree) with 92% of medium and small fruits of good quality (not stained). Retail prices were: $100 percent of large walnut, $80 percent of medium walnut, $60 percent of small nut, and an equivalence of 80 fresh fruits with different shell sizes per kilogram was considered. The average price considered in this system, according to the recorded harvest and according to the percentages of fruits per size was $ 61.54 kg-1 (MXN) - price directly to the consumer- In this system are not considered costs of spraying, fertilizing, or irrigation. The work hickory considered were: land leveling, trenching, opening strains, planting, weeding, harvesting, peeling and washing nut to bone. It did not help irrigation in dry season or spraying the walnut.

The corn planting is temporary and in full for their own consumption. The average corn yield recorded in the region is 2.8 t ha-1. In interspersed with walnut with an array of 5 rows of walnut in a planting of 10 X 10 m system, a yield of 1 728 t of corn was estimated (with 30 000 plants). The work considered to corn were fallow, furrowed, seed, animal fertilization, carved 1st, 2nd tilled, weed control, pinch, lifting and husking grass. The corn crop was between November and December. The price of a tons of grain corn in 2011 was $3 500.00 MXN, according to field data recorded in this research, which means an equivalent income from the sale of 100% corn $6 048.00 MXN.

The walnut orchard in temporary system. Planting walnut orchard is performed only by 6% of producers throughout the region Sierra Nevada. Cost analysis income was considering a hectare. The population density was considered in the analysis was 10 rows of walnut in a planting of 10 X 10 m, giving a total of 100 walnut trees ha-1. The walnut harvest season is from late July until early in September.

Performance data were obtained from a farm in production system orchard located in the town of San Rafael Ixtapalucan, Santa Rita Tlahuapán, located at coordinates 19.27683" north latitude 98.54324" west ± 3", at a altitude of2 502 m with trees of between 4 to 6.4 m tall. Performance was measured by counting the number of small, medium and large fruits harvested in 2011 in a single cut. An average yield of 1.619 thousands per tree (equivalent to 20.237 kg per tree nut shell) was obtained; with 12% of large fruits, 56% of medium fruits, 24% of small fruits of good quality (not stained) and 8% of tainted fruits. The prices considered were: $100 percent of large walnut, $80 percent of medium walnut, $60 percent of small nut, and an equivalence of 80 fresh fruits in shell of different sizes per kilogram in trees of 30 years old was considered. The average price considered in this system, according to the registered and according to the percentages of fruits per size harvest was $ 60.5 kg-1 (mxn) fresh walnut shell sold per thousand directly in local markets (prices of 2011). Prices grew by 20% in 2015 ($120 per one hundred large walnut, $100.00 for a hundred medium walnut and $80 for a hundred small walnut).

For the study it found that the tree went into production at 5 years with a yield of 0.9 kg per tree (when plants were planted 3 years of growth); per year it increased its production by 0.74 kg and 0.79 kg the last two years and reached a production of 20 237 kg/tree at age 30. In this system, the work considered were: land leveling, plowing, opening strains, planting, spraying, irrigation help, weeding, harvesting, peeled nut to bone, washing and freight to Central of Supplies Mexico. The 2 irrigations were made in the dry season (January-February) and sprayed 5 times before harvest (March to June) with chemicals (Malathion). The producer does not have agricultural equipment nor vehicle so that no diesel costs were considered. The irrigation and spraying relief payment for services considered.

Profitability and competitiveness

A private prices the benefit-cost ratio (RB/C) in the production system MIAF (corn-walnut), to a horizon of 30 years considering growth rates to a historical inflation rate of 4.4% per year, was 1.19 with an VAN of $27.182 pesos and an TIR of 39%. For the orchard system an RB/C of 7.7 with a VAN of $118.210 pesos and a TIR of 18%. The updated 2015 showed a slight growth indicators: RB/C 1.22, TIR 40% and VAN of $33.795; RB/C 8.72, TIR 19% and VAN $ 150 790 pesos, respectively.

A low prices the (RB/C) in the production system MIAF (corn-walnut), to a horizon of 30 years, considering price growth to a historical inflation rate of 4.4% per year, had an RB/C of 0.79 with a negative VAN of 121 799 pesos and a negative TIR of 3%. For the orchard system an RB/C of1.03 with a VAN of 18 559 pesos and a TIR of 6%. The indicators remain negative with prices updated in 2015, and the orchard system reduces their competitiveness, considering the price of fresh nut in Central of Supplies Mexico put at a price per kilogram of $37.63 pesos. In both systems salaries represent the largest share of the costs (48% and 43%, respectively).

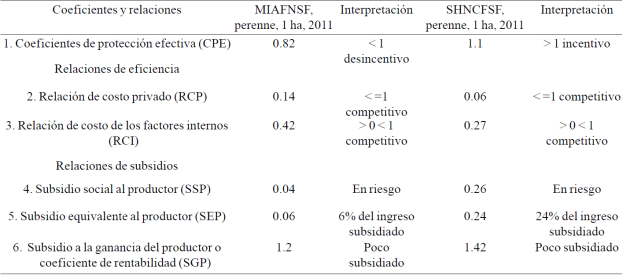

Note that in the system MIAF total production costs are greater than the costs of the orchard system in 17.6%, whose net income represents only 46% of the net profit private prices orchard system. Profit becomes negative to transform private economic prices, particularly for fertilizers and chemicals valued at international prices used in corn and Orchard, respectively, and the opportunity cost considered. The effect of positive economic policy, caused by water subsidy, is unrepresentative in the cost structure (2% MIAF and 11% Orchard), being temporary systems. The CPE (0.82 and 1.1) states that the MIAF system is not protected by the current economic policy and the orchard system is protected by 10%. That is, the producer of MIAF system is receiving lower earnings to which receive without policy intervention. Meanwhile, the producer orchard, receives a higher income, with a higher added value to the current economic policy.

The RCI coefficient of 0.42 to MIAF and 0.27 for orchard, says that for every peso 42 and 27 cents, respectively, are for payment of internal factors and 58 and 73 cents are possible usefulness. The RCP coefficient of 0.14 and 0.06 shows that both systems are competitive because if they pay the cost of inputs (Table 1). Moreover, the traditional system of walnuts a social function and enables farmers to generate income (Mendoza et al., 2010). The added value in both systems is similar - MIAF (96.4), Orchard (98.6) -respect the remuneration to labor, capital and land, while intermediate consumption represents 3.6% and 1.4% of total revenue, which refers payment of tradable inputs. The ratio of allowance (SSP) said that the government should support 96% and 74% to the producer to maintain the current level of private profit in the event of total trade and opening high TC. The updated 2015 data showed similar results to private prices but at affordable prices become unprofitable.

Table 1 Coefficients protection and efficiency ratios nut in the region of Castilla Sierra Nevada, Puebla.

Donde: SHNCFSF= sistema Huerto de nogal con fumigación sin fertilización; SPTNHM= sistema de producción tradicional de nuez de Castilla en huerto a precios medios.

While local culture has competitive advantage to private prices, affordability is not so. The good price the regional market pays benefits the product, but the low yield and low level of consumption, related management system and poor manufacturing practices of the fruit, threatening traditional production systems walnuts in the region Sierra Nevada.

Conclusions

Traditional production systems walnuts are unprofitable private prices because the price of fertilizer used in growing corn and the opportunity cost which means flower production. However, both systems are competitive, with a greater degree the traditional system, to generate higher added value -salary- valued in economic terms. Both systems analyzed are competitive compared with each other; the orchard receiving protection system, policy measures expressed in economic and internal factors subsidy prices.

Otherwise, economic policy does not protect the traditional MIAF system. In both systems the presence of minimal transfers, according to the values SEP showing just above unity indicators identified. Which generally indicates the high risk of competitiveness and profitability which are both production systems to the Mexican and global trade and exchange rate policy.

On the other hand, the marketing mechanisms indicate a functional chain, with a strong dose of tradition, based on trust and respect between the players involved; with a strong development perspective, represented by a growing specialized in the preparation of chili in walnut sauce and consumer demand in the use of creole nut market for their preparation. So it will be necessary to strengthen actions to add value and mechanisms to increase the quality, agronomic management and presentation of the fruit, the economic competitiveness of the crop. Respecting the rationality of smallholder-farmers based on a relationship of respect between man and nature suggesting profitability and social and environmental efficiency.

Literatura citada

Álvarez, M. M. de L. 2003. Competencias centrales y ventaja competitiva: el concepto, su evolución y aplicabilidad. Revista Contaduría y Administración. 209:5-22. [ Links ]

Altieri, M. y Nicholls, C. 2000. Agroecología teoría y práctica para una agricultura sustentable. ONU-PNUMA. (México) 1a edición. 250 p. [ Links ]

Barrera, R. A.; Jaramillo, V. J. L.; Escobedo, G. J. S. y Herrera, C. B. E. 2011. Rentabilidad y competitividad de los sistemas de producción de vainilla (Vanilla planifolia J.) en la Región del Totonacapan, México. Rev. Agroc. 45:625-638. [ Links ]

Camacho, H.; Fernández, T. y Sánchez, M. B. 2000. Tesis proyecto de inversión para la producción y comercialización de la nuez de castilla. Facultad de Administración de Empresas, Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla. 207 p. [ Links ]

González, J. A. 2003. Cultura y agricultura: transformaciones en el agro mexicano. Universidad Iberoamericana. México, D. F. 1a Edición. 339 p. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2011. Enciclopedia de los municipios de Puebla. México. 1146 p. [ Links ]

Kresl, P. and Singh, B. 1999. Competitiveness and the urban economy: twenty-four large US metropolitan areas. Urban Studies. 5-6(36):1017-1027. [ Links ]

Lara, C. D.; Mora, F. J. S.; Martínez, D. M. A.; García, D. G.; Omaña, S. J. M. y Gallegos, S. J. 2003. Competitividad y ventajas comparativas de los sistemas de producción de leche en el estado de Jalisco, México. Agrociencia. 1(37):85-94. [ Links ]

Lemus, G. 2010. Manuales FIA de apoyo a la formación de recursos humanos para la innovación agraria. Producción de nueces de nogal. Ministerio de Agricultura de Chile. Salvat Impresores. 100 p. [ Links ]

Luna, M. N.; Jaramillo, V. J. L.; Ramírez, J. J.; Escobedo, G. J. S.; Bustamante, G.A. y Campos, R. G. 2013. Tipología de unidades de producción de nuez de castilla en sistema de producción Tradicional. Rev. Agric. Soc. Des. 3(10):283-303. [ Links ]

Magaña, M. M. A.; Matus, G. J. A.; García, M. R.; Santiago, C. M. de J.; Martínez, D. M. A. y Martínez, G. A. 2002. Rentabilidad y efectos de política económica en la producción de carne de cerdo en Yucatán. México. Agrociencia. 6(36):737-747. [ Links ]

Mendoza, R. R.; Parra, I. F. y De Los Ríos, C. I. 2010. La actividad frutícola en tres municipios de la Sierra Nevada en Puebla: características, organizaciones y estrategia de valorización para su desarrollo. Agric. Soc. Des. 3(7):229-245. [ Links ]

Monke, E. A. and Pearson, S. R. 1989. The policy analysis matrix for agricultural development. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, N.Y., U.S.A. 109-151 pp. [ Links ]

Morales, A. A. y Rendón, T. A. 2000. La competitividad industrial, su medición. Revista Política y Cultura. 13:187-213. [ Links ]

Rendón, T. A. y Morales, A.A. 2001. Modelos econométricos para analizar el impacto de variables económicas en la competitividad de la industria del calzado. México. Revista Política y Cultura. 15:1-25. [ Links ]

USDA. 2011. Department of Agriculture. www.usda.gov . Consultado 10/11/11. [ Links ]

USDA-NASS. 2013. California Walnut Objective Measurement Report. [ Links ]

Received: June 2016; Accepted: August 2016

texto en

texto en