Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 n.6 Texcoco Aug./Sep. 2016

Articles

Effect of Glomus fasciculatum and its relationship with three organic fertilizers on two broad bean cultivars

1Posgrado en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Recursos Naturales-Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEMex.). Campus Universitario “El Cerrillo”. El Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, municipio de Toluca, Estado de México (CPB-TEM).

2Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados en Fitomejoramiento. Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas. UAEMex-CPB-TEM. A. P. 435. Tel. y Fax: 01(722) 2965518. Ext. 148. (agonzalezh@uaemex.mx; ofrancom@uaemex.mx; mrubia@uaemex.mx; luishalc@mailcity.com).

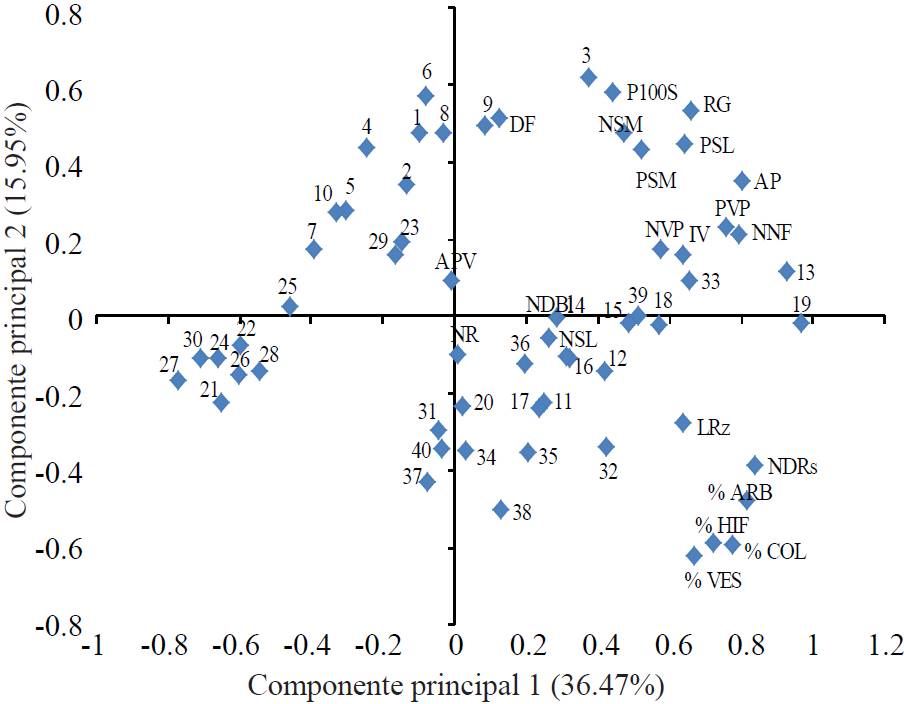

The interest of broad bean producers is to weigh between sustainability and economy; high production and quality could be obtained with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (HMA) and organic fertilizers. This work was established at the Experimental Field Ranch "San Lorenzo" located in the municipality of Metepec, State of Mexico. The main objective was to evaluate Glomus fasciculatum with vermicompost, manure and mushroom compost in 1, 2 and 3 t ha-1 and N60-P60-K30 applied in two broad bean cultivars. The 40 treatments were randomized in an experimental design in a randomized complete block with three replications, in split plot arrangement; both cultivars with and without mycorrhiza (C + M) were big plot and the type and amount of fertilizer the small plot (B). The experimental unit consisted of three rows of 4 x 0.80 m. The distance between plants was 0.40 m. Significant differences were detected for both factors and in their interaction in 19 of the 21 variables. When applying G. fasciculatum the cv. San Pedro (C1) expressed the highest average in NNF, AP, IV, NVP, PVP, PSL, P100 S, RG,% COL, LRz, NRs, NBs,% VES and %ARB. Chicken manure and mushroom compost with 3 t ha-1 favored a better phenotypic expression in most of the variables evaluated. C1 with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure and HMA showed the best behavior for AP, IV, NVP, PSL, P100S, and RG (2.63 t ha-1). C1 with 3 t ha-1 of mushroom and mycorrhizal originated higher %COL (72.20%) and ARB (71.46%). cv. Santiago (C2) with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure and HMA showed the highest PVP (124.10 g), NSL (32.63), PSL (62.40 g), RG (2.40 t ha-1),% ARB (73.30) and %hyphae (8440). The main components 1 and 2 explained 52.42% of original total variation.

Keywords: Vicia faba; mycorrhiza; organic fertilizers; Valles Altos del Centro de Mexico

El interés de los productores de haba es ponderar entre sustentabilidad y economía; una producción alta y de calidad podría obtenerse con hongos micorrízicos arbusculares (HMA) y abonos orgánicos. El presente trabajo se estableció en el Campo Experimental Rancho “San Lorenzo”, ubicado en el municipio de Metepec, estado de México. El objetivo principal fue evaluar Glomus fasciculatum con lombricomposta, gallinaza y composta de champiñón en 1, 2 y 3 t ha-1 y N60-P60-K30 aplicado en dos cultivares de haba. Los 40 tratamientos se aleatorizaron en un diseño experimental de bloques completos al azar con tres repeticiones, en arreglo de parcelas divididas; ambos cultivares con y sin micorriza (C+M) fueron la parcela grande y el tipo y la dosis de abono la parcela chica (B). La unidad experimental constó de tres surcos de 4 x 0.80 m. La distancia entre plantas fue de 0.40 m. Se detectaron diferencias significativas para ambos factores y en su interacción en 19 de las 21 variables. Al aplicar G. fasciculatum el cv. San Pedro (C1) expresó el mayor promedio en NNF, AP, IV, NVP, PVP, PSL, P100 S, RG, %COL, LRz, NRs, NBs, % VES y % ARB. La gallinaza y la composta de champiñón con 3 t ha-1 favorecieron una mejor expresión fenotípica en la mayoría de las variables evaluadas. C1 con 3 t ha-1 de gallinaza y HMA mostró el mejor comportamiento para AP, IV, NVP, PSL, P100S, y RG (2.63 t ha-1). C1 con 3 t ha-1 de champiñón y micorrizas originó mayor % COL (72.20%) y de ARB (71.46 %). El cv. Santiago (C2) con 3 t ha-1 de gallinaza y HMA mostraron el mayor PVP (124.10 g), NSL (32.63), PSL (62.40 g), RG (2.40 t ha-1), % ARB (73.30) e % hifas (84.40). Los componentes principales 1 y 2 explicaron 52.42% de la variación total original.

Palabras clave: Vicia faba; abonos orgánicos; micorrizas; Valles Altos del Centro de México

Introduction

In recent years, the indiscriminate use of pesticides has affected soil fertility and ecosystems, so it has arisen the need to develop new environmental strategies based on beneficial biological interactions that will increase the availability of nutrients (Rojas and Ortuño, 2007). Mycorrhizae and atmospheric N2-fixing bacteria, known as biofertilizers, favor the development of plants (West et al., 2009). Vermicompost, manure and mushroom residue contribute organic matter (Eghball et al., 2002).

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (HMA) act as growth accelerator by increasing phosphorus absorption and help in protecting against pathogens (Alarcón and Ferrera, 1999, 2000; Mena et al., 2006; West et al., 2009; Smith and Smith, 2011; Singh et al., 2013); tt can also influence the structural and soil aggregation process (Rilling and Mummey, 2006). Within the HMA is Glomus with 85 species, but the most important in agriculture is G. fasciculatum, studied in fruit, forestry, vegetables and legumes. There are reports of the positive effect of it with compost, manure or crop residue (Saif, 1986) by increasing the potential of inoculum in the soil, colonization and nutrient uptake (Gosling et al., 2006; Wu and Zou, 2010; Singh et al., 2013; Dutt et al., 2013).

The application of vermicompost in serrano pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) caused more than 70% of colonization (Manjarrez et al., 1999). Broad bean (Vicia faba L.) has great importance as a rotation crop for their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen (Kalia and Sood, 2004); it is the seventh largest leguminous in the world and consumed in fresh and dry. This is a culture of high protein (23-43%) and economic for the low-income population (Perez et al., 2014). The main countries contribute 57% of worldwide production (FAOSTAT, 2013).

In Mexico it is a growing alternative for the states of Puebla, Mexico, Tlaxcala, Veracruz and Michoacán where almost 90% of its surface is sown under rainfed (SIAP, 2013), but in recent years has decreased its interest and yield per hectare due to rapid depletion of organic matter and soil nutrient imbalance. Currently the main interest of producers is to weigh between sustainability and economy; thus, the use of mycorrhizae and organic fertilizers is a viable option to reduce damage to the ecosystem.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of G. fasciculatum with three organic fertilizers and fertilizer formula in grain yield and other pod, plant and root characteristics of two broad bean cultivars.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

This work was developed in 2013 at the Ranch "San Lorenzo" located in Metepec, State of Metepec, at an altitude of 2606 m, located at 19° 14' 866'' north latitude and 99° 35' 240'' west longitude. The predominant climate is C (W2) (W) (Oi) corresponding to temperate g with summer rains, average annual temperature 13 °C, with frequent frosts from October to March and an annual rainfall of 785 mm (Pérez et al., 2014). The most common soil is andosol, rich in organic matter.

Genetic material

Two cultivars were used: San Pedro Tlaltizapán (C1) and Santiago Tianguistenco (C2); C1 was provided by the Research Institute and Agricultural, Aquaculture and Forestry Training of the State of Mexico (ICAMEX) and was characterized by Pérez et al. (2014). C2 is a collection which is name by their place of origin.

Treatment structure

Vermicompost, manure and mushrooms were considered in 1, 2 and 3 t ha-1 and the formula N60-P60-K30. 10 combinations of fertilizers and both cultivars with and without G. fasciculatum originating 40 treatments (Table 1).

Table 1. Factors and levels of study.

| Factores | Niveles |

|---|---|

| Cultivares + micorrizas (Factor A) | C1+SM = San Pedro sin micorriza |

| C1+ M = San Pedro con micorriza | |

| C2 + SM = Santiago sin micorriza | |

| C2 + M = Santiago con micorriza | |

| Tipo de fertilización (Factor B) | B1= Gallinaza, 1 t ha-1 |

| B2= Gallinaza, 2 t ha-1 | |

| B3= Gallinaza, 3 t ha-1 | |

| B4= Lombricomposta, 1 t ha-1 | |

| B5= Lombricomposta, 2 t ha-1 | |

| B6= Lombricomposta, 3 t ha-1 | |

| B7= Champiñón, 1 t ha-1 | |

| B8= Champiñón, 2 t ha-1 | |

| B9= champiñón, 3 t ha-1 | |

| B10= N60-P60-K30 |

Design and plot size

The 40 treatments were randomized in the field under an experimental design of randomized complete block with three replications in a split plot arrangement: both cultivars with and without mycorrhiza were assigned to big plot and the nine organic fertilizers and chemical formula formed the small plot (Table 1). The plot consisted of three rows of 9.6 m2 with plants spaced at 0.40 m; the useful plot was the central row (3.2 m2).

Inoculation

For G. fasciculatum suggested 2 kg ha-1, with 79 spores per g. 0.9 g of inoculum were weighted for each treatment, the night before seeding was applied to the seed and this were disinfected with sodium hypochlorite at 5% for three minutes and then washed with water. The "garapiñado" technique consisted of 300 g of sugar dissolved in 1 L of water; in this the seeds were immersed for 10 seconds, then drained and dusted with mycorrhizal inoculum; the samples were dried on a blanket in absence of light.

Development of experimental work

Soil preparation consisted of fallow and harrowing. Manual seeding was held on April 17 2013. Treatment 60 N-60P-30K was prepared with urea (46% N), triple calcium superphosphate (46% P) and potassium chloride (60% K). Along sowing incorporated manure, vermicompost and mushroom compost in 1, 2 and 3 t ha-1. The chemical composition of fertilizers are shown in Table 2. On April 24 was applied an irrigation. Weeding out were held on May 13 and July 4. Weed control was manual. To prevent diseases applied 1 kg ha-1 of Manzate (mancozeb). To reduce disease incidence applied Rogor (dimethoate) at doses of 250 g in 100 L of water, before flowering; also applied 100 L ha-1 of Anasac (Cyhalotrin) to control aphids. Harvest was made in December 2013.

Table 2. Physico-chemical composition of the three organic fertilizers.

| Características | Lombricomposta (L *) | Gallinaza (G**) | Composta de hongo (H***) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humedad (%) | 20 a 40 | 5 -55 | ------ |

| pH | 5.5 a 8.5 | 7 -7.8 | 6-8.4 |

| Materia orgánica (%) | 20 a 50 | 25 a35 | 36.98 |

| Relación C/N | ≤ 20 | 8 a14 | ≤ 14.1 |

| Conductividad eléctrica | ≤ 4 dS cm-1 | 13.48 | 15.86 |

| Capacidad de intercambio catiónico (CIC) | ˃40 cmol Kg-1 | -------- | ˃33.7 cmol Kg-1 |

| Densidad aparente (DA) | 0.40 a 0.90 g mL-1 | 0.74 g cm-3 | 0.37 g cm-3 |

| N total (%) | 1 - 4 | 2.5 -5 | 1.52 |

| P (%) | 2.18 | 1.0-3.5 | 203.8 ppm |

| K (%) | 0.79 | 1.4 -4 | 319.3 ppm |

| Ca (%) | 1.33 | 5.6 | 176.9 ppm |

| Mg (%) | 1.21 | 0.7 | 270.5 ppm |

| Na (%) | 0.12 | -------- | 142 ppm |

| Carbono orgánico (%) | 18.57 | -------- | 21.45 |

Study variables

10 plants were selected in the useful plot and recorded: days to flowering (DF), floral knots (NNF, in its central axis), plant height (AP: cm from the base of the main stem), height to the first pod (APV: cm from the base of the main stem to the base of the first pod), leaf greenness index (IV: determined with SPAD 502 plus), branches per plant (NR), pods per plant (NVP), weight pod per plant (PVP: was determined in g with a digital scale), clean seeds (NSL), stained seeds (NSM), weight of clean seeds (PSL: g), weight of stained seed (PSM, g), 100 seeds weight (PS100, g) and grain yield (RG, t ha-1) (Pérez et al., 2014).

For colonization were randomly selected three plants in each useful plot, with destructive sampling and recorded root length (LR, cm), pink nodules (NDRs, with a colony counter Q-14 Solbat), white nodules (NDBl, with colony counter Q-14 Solbat), colonization [% COL: with Philips and Hayman (1970) technique from 10 fragments stained root of 1.0 cm in length recording the presence of self-structures of the fungus MA per each optical space of microscopic observation at 400x. The number of fields in which some structure was seen was considered on the number of fields seen and multiplied by 100. Then quantified the presence of fungal structures; [Vesicles (% VES), arbuscules (% ARB) and hyphae (% HIF)]. To stain root samples the following reagents were used potassium hydroxide 10%, hydrogen peroxide 10%, hydrochloric acid IN, lacto-glycerol and blue tryptophan 0.05%.

Statistic analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance and mean comparison with Tukey test (α= 0.01). Arithmetic means from the 40 treatments for 21 variables were used to generate the data matrix that allowed to obtain the principal component analysis (Sánchez, 1995; Pérez et al., 2014).

Results and discussion

Variance analysis

The effects for both factors and their interaction were significant in 19 of the 21 variables (Table 3); the levels from factor A (cultivar + mycorrhiza) were significantly different (p= 0.01) in 20 variables. The ten levels from factor B (fertilizer) contributed to phenotypic differentiation (p= 0.01) of DF, NNF, AP, APV, IV, NR, NVP, PVP, NSL, PSL, P100S, RG, LRz, NDRs, NDBs,% COL, %VES, %ARB and %HIF. These results show a favorable response in Vicia faba using mycorrhizae (Gosling et al., 2006) and organic fertilizers (Castro et al., 2009; Álvarez et al., 2010). A x B interaction was also significant. In another study, there was positive effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal with composted manure or crop residue (Saif, 1986) by increasing the potential of mycorrhizal inoculum in the soil.

Table 3. Mean squares and statistical significance of the values of F for flowering (DF), floral knots (NNF), plant height (AP) and first pod (APV), greenness index (IV), number of branches (NR ), pods per plant (NVP), weight of pod per plant (PVP), stained seeds (NSM), weight of stained seed (PSM), clean seeds (NSL), weight of clean seed (PSL), 100 seeds weight (P100S), grain yield (RG), root length (LRZ), pink nodules (NDRs), white nodules (NDB), colonization (% COL), vesicles (% VES), arbuscules (% ARB) and hyphae (% HIF).

| FV | gl | DF | NNF | AP | APV | IV | NR | NVP |

| R | 2 | 201.3 ns | 5.99 ns | 72.12ns | 2.27ns | 3.57ns | 0.13ns | 5.02ns |

| Error a | 6 | 124.9 | 1.27 | 41.92 | 0.63 | 3 | 0.11 | 0.99 |

| T | 39 | 481.99** | 4.77** | 401.96** | 14.8** | 22.86** | 0.48** | 71.41** |

| Factor A (C+M) | 3 | 1909.49** | 37.1** | 3417.31** | 15.46** | 30.85** | 0.9** | 40.41** |

| Factor B (Abonos) | 9 | 365.28** | 5.40* | 325.82** | 23.73** | 68.55** | 0.26** | 267.68** |

| A x B | 27 | 362.28** | 0.974** | 92.3** | 11.74** | 6.75** | 0.51** | 9.42** |

| Error b | 72 | 38.42 | 0.357 | 16.62 | 1.39 | 2.36 | 0.072 | 1.86 |

| Total | 119 | |||||||

| CV (%) | 10.36 | 4.38 | 4.11 | 5.22 | 3.19 | 8.55 | 7.57 | |

| X | 59.82 | 13.62 | 99 | 22.6 | 48.22 | 3.4 | 18.02 | |

| FV | gl | PVP | NSM | PSM | NSL | PSL | P100 S | RG |

| R | 2 | 350.68** | 6.56 ns | 50.56 ns | 12.16 ns | 48.03 ns | 29.38 ns | 0.88 ns |

| Error a | 6 | 34.21 | 9.21 | 25.51 | 17.62 | 64.2 | 79.92 | 0.66 |

| T | 39 | 1052.7** | 4.87* | 22.46** | 80.70** | 215.96** | 8066.25** | 0.26* |

| Factor A (C+M) | 3 | 2436.58** | 23.53ns | 183.12* | 367.31** | 656.77** | 101774.44** | 0.72 ns |

| Factor B(Abonos) | 9 | 3051.69** | 2.95 | 11.08 | 164.06** | 417.65** | 303.31** | 0.61** |

| AxB | 27 | 232.62** | 3.45ns | 8.41 | 21.06** | 99.75** | 241.97** | 0.09ns |

| Error b | 72 | 80.08 | 2.3 | 6.57 | 7.34 | 24.31 | 85.45 | 0.135 |

| Total | 119 | |||||||

| CV (%) | 10.33 | 21.8 | 19.39 | 13.09 | 10.47 | 3.76 | 18.55 | |

| X | 86.57 | 6.95 | 13.22 | 20.7 | 47.09 | 245.37 | 1.98 | |

| FV | gl | LRz | NDRs | NBl | %COL | %VES | %ARB | %HIF |

| R | 2 | 2.13 ns | 3.34 ns | 0.046 ns | 24.18 ns | 1.39ns | 19.78 ns | 7.87 ns |

| Error a | 6 | 2.34 | 0.78 | 0.3 | 11.68 | 3.15 | 27.5 | 2.36 |

| T | 39 | 24.84** | 144.95** | 8.36** | 1417.63** | 1537.55** | 2054.74** | 1618.49** |

| Factor A (C +M) | 3 | 144.75** | 1659.24** | 10.52** | 17371.87** | 16093.16** | 23872.01** | 17735.85** |

| Factor B (Abonos) | 9 | 19.64** | 25.11** | 9.25** | 120.24** | 223.44** | 281.61** | 356.44** |

| A x B | 27 | 13.25** | 16.64** | 7.82** | 77.4** | 358.3** | 221.64** | 248.35** |

| Error b | 72 | 1.03 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 10.89 | 13.28 | 12.74 | 12.28 |

| Total | 119 | |||||||

| CV (%) | 5.40 | 5.28 | 6.14 | 9.31 | 8.96 | 12.98 | 8.88 | |

| X | 18.78 | 17.9 | 8.74 | 35.42 | 40.65 | 27.49 | 39.44 | |

Comparison of means for factor A (cultivar + mycorrhizae) With G. fasciculatum cv. San Pedro (C1) expressed the average maximum in floral knots (15.5), plant height (111.01 cm), greenness index (49.01), pods per plant (18.45) and pod weight per plant (48.48 g). This response was similar to that reported by Wu and Zou (2010) in citrus by adding mycorrhizae. In weights of seed, 100 seeds weight and grain yield were statistically equal to control; the two cultivars had the highest seed weight per plant by adding mycorrhizae. cv. San Pedro showed significant differences (α= 0.01) in root length, pink nodules, white nodules, and colonization percentages of vesicles and arbuscules. Root length (21.50 cm) was higher than that reported by Thanuja et al. (2002; 9.95 cm), but colonization (58.58%) was lower than that reported by them (79.17%), the percentage of arbuscules was 54.05; this characteristic is important because with these values there is greater absorption of nutrients and symbiosis (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of means of factor A (cultivar ± mycorrhizae) to flowering (DF), floral knots (NNF), plant height (AP), first pod height (APV), greenness index (IV), number of branches (NR) and pods per plant (NVP).

| Factor A | DF | NNF | AP | APV | IV | NR | NVP |

| C1 - M | 69.23 a | 13.56 b | 103.05 b | 22.27 bc | 47.97 ab | 2.92 b | 16.95 b |

| C1 + M | 63.44 b | 15.15 a | 111.01 a | 22.84 ab | 49.02 a | 3.13 ab | 18.45 a |

| C2 - M | 54.86 c | 12.49 c | 85.87 d | 23.47 a | 46.89 b | 3.34 a | 17.22 b |

| C2+ M | 51.77 c | 13.29 b | 96.07 c | 21.82 c | 49.00 a | 3.17 a | 19.46 a |

| DMSH | 5.16 | 0.49 | 3.39 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 0.22 | 1.13 |

| Factor A | PVP | NSM | PSM | NSL | PSL | P100s | RG( tha-1) |

| C1 - M | 83.04 bc | 7.8 a | 15.48 a | 17.89 c | 50.77 a | 298.36 a | 2.07 a |

| C1 + M | 98.42 a | 6.91 ab | 13.76 a | 18 c | 48.48 a | 292.88 a | 2.11 a |

| C2 - M | 77.11 c | 5.77 b | 9.7 b | 21.67 b | 40.23 b | 189.55 c | 1.76 a |

| C2 + M | 87.71 b | 7.27 a | 13.94 a | 25.24 a | 48.88 a | 200.7 b | 1.96 a |

| DMSH | 7.45 | 1.26 | 2.13 | 2.25 | 4.1 | 7.69 | 0.3 |

| Factor A | LRz | NDRs | NDBl | % COL | % VES | % ARB | % HIF |

| C1 - M | 17.42 c | 12.59 c | 8.84 b | 14.41 c | 20.48 b | 4.37 c | 18.37 c |

| C1+M | 21.5 a | 26.76 a | 9.3 a | 58.58 a | 59.61 a | 54.05 a | 58.87 b |

| C2 - M | 16.64 c | 10.98 d | 7.9 c | 14.9 c | 20.72 b | 1.88 c | 18.45 c |

| C2+ M | 19.57 b | 21.28 b | 8.92 ab | 53.81 b | 61.77 a | 49.66 b | 62.06 a |

| DMSH | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.44 | 2.74 | 3.03 | 2.97 | 2.91 |

In pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) a reduction in arbuscules (21.6%), vesicles (42.89%), and total root colonization (62.7%) was observed regarding to control by inoculating with G. fasciculatum (Davies et al., 2002). Dutt et al. (2013) mentioned that it was more effective the inoculation in Prunus armeniaca L. with G. fasciculatum.Singh et al. (2013) reported 71% colonization by combining G. fasciculatum and G. monteilii in Coleus forskohlii and with G. fasciculatum this was 65%. In another study the addition of G. fasciculatum resulted in an increase in N, P. K, Ca, and Mg, soluble sugars, free amino acids, proline accumulation and presence of a peroxidase and catalase in saline conditions with wheat (Talaat and Shawky , 2011). Moreover sucrose increased in citrus by applying Funneliformis masseae (Wu et al., 2013). Inoculation with G. fasciculatum in four forest species in field and nursery resulted in an increase of basal diameter, plant height, dry weight of foliage and root and nutrients up take (Hernández and Salas, 2009).

Factor B (organic fertilizers)

Chicken manure (B3) and mushroom compost (B9) in 3 t ha-1 showed the best phenotypic expression in floral knots (NNF), plant height (AP), greenness index (IV), pods per plant (NVP ), pod weight per plant (NVP), clean seeds (NSL), weight of clean seeds (PSL), 100 seed weight and grain yield (RG 2.42 t ha-1) (Table 5). These results are similar to Pool et al. (2000) who obtained an increase in yield of maize (Zea mays L.) and cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) attributable to increased phosphorus in poultry manure (Orozco and Thienhaus, 1997). In potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) the addition of organic fertilizers caused increased production and quality of tuber (Romero et al., 2000).

Table 5. Comparison of means of factor B to flowering (DF), floral knots (NNF), plant height (AP), height to the first pod (APV), greenness index (IV), number of branches (NR) and pods per plant (NVP).

| Abonos | DF | NNF | AP(cm) | APV(cm) | IV | NR | NVP |

| B1 | 58.67 abcd | 13.25 b | 97.13 b | 23.60 ab | 44.77 g | 3.21 ab | 14.81 d |

| B2 | 58.04 bcd | 13.19 b | 100.28 b | 20.59 cd | 49.17 bcd | 3.13 ab | 21.23 b |

| B3 | 64.63 ab | 14.86 a | 107.26 a | 22.63 ab | 51.76 a | 3.39 a | 26.2 a |

| B4 | 67.08 ab | 13.47 b | 96.47 b | 23.16 ab | 45.52 fg | 3.06 ab | 14.34 de |

| B5 | 62.32 abc | 13.33 b | 96.83 b | 23.81 ab | 47.95 cde | 3.05 ab | 14.63 d |

| B6 | 68.25 a | 13.85 b | 95.17 b | 22.02 bc | 47.59 def | 3.38 a | 18.95 c |

| B7 | 54.42 cd | 13.16 b | 95.06 b | 23.58 ab | 48.20 cde | 3.14 ab | 15.22 d |

| B8 | 54.59 cd | 13.35 b | 96.08 b | 23.96 a | 50.11 abc | 3 ab | 17.51 c |

| B9 | 57.89 bcd | 14.78 a | 109.61 a | 22.83 ab | 51.25 ab | 3.1 ab | 24.91 a |

| B10 | 52.34 d | 12.99 b | 96.08 b | 19.81 d | 45.87 efg | 2.95 b | 12.38 e |

| DMSH | 9.65 | 0.93 | 6.35 | 1.83 | 2.39 | 0.41 | 2.12 |

| Abonos | PVP(g) | NSM | PSM(g) | NSL | PSL(g) | P100s (g) | RG(t ha-1) |

| B1 | 81.18 bc | 7.25 a | 13.18 a | 18.55 cd | 43.53 cde | 247.20 ab | 1.83 bc |

| B2 | 85.43 bc | 6.59 a | 12.76 a | 22.32 bc | 47.00 cd | 245.54 ab | 1.95 abc |

| B3 | 115.15 a | 7.95 a | 14.53 a | 28.33 a | 57.86 a | 255.33 a | 2.42 a |

| B4 | 75.71 cd | 6.66 a | 13.75 a | 16.59 d | 46.11 cd | 237.08 b | 2.00 abc |

| B5 | 84.73 bc | 6.50 a | 14.03 a | 20.37 cd | 47.40 bcd | 245.50 ab | 2.05 abc |

| B6 | 92.49 b | 6.77 a | 13.08 a | 20.64 bcd | 49.52 bc | 243.66 ab | 1.82 bc |

| B7 | 74.54 cd | 6.29 a | 11.15 a | 18.30 cd | 37.74 e | 240.39 b | 1.65 c |

| B8 | 83.95 bc | 7.27 a | 13.67 a | 20.64 bcd | 45.39 cde | 242.45 ab | 2.00 abc |

| B9 | 110.06 a | 7.31 a | 12.35 a | 24.80 ab | 54.69 ab | 249.16 ab | 2.25 ab |

| B10 | 62.45 d | 6.95 a | 13.67 a | 16.45 d | 41.66 de | 247.50 ab | 1.80 bc |

| DMSH | 13.94 | 2.36 | 3.99 | 4.22 | 7.68 | 14.40 | 0.57 |

| Abonos | LRz(cm) | NDRs | NDBl | %COL | %VES | %ARB | %HIF |

| B1 | 20.6 a | 16.8 de | 8.57 cd | 31.65 cd | 41.18 bcd | 25.65 bcd | 38.27 cd |

| B2 | 17.7 cde | 18.31 bc | 9.12 bc | 36.53 acb | 47.87 a | 30.1 bc | 42.97 bc |

| B3 | 18.06 cde | 20.78 a | 7.16 e | 37.99 ab | 40.09 bcd | 36.78 a | 45.54 ab |

| B4 | 17.05 e | 17.06 cd | 7.84 de | 36.39 abc | 38.55 cd | 30.65 b | 41.24 bcd |

| B5 | 19.93 ab | 18.86 b | 8.3 cd | 34.4 bcd | 43.28 abc | 27.47 bc | 40.76 bcd |

| B6 | 19.25 abc | 16.93 cde | 8.99 bc | 30.4 d | 32.17e | 27.72 bc | 32.3 e |

| B7 | 18.05 cde | 18.71 b | 8.52 cd | 34.35 bcd | 39.89 bcd | 20.25 d | 31.76 e |

| B8 | 19.01 bcd | 17.76 bcd | 9.1 bc | 40.7 a | 44.53 ab | 24.97 cd | 48.56 a |

| B9 | 20.57 ab | 18.31 bc | 10.33 a | 38.32 ab | 36.89 de | 30.07 bc | 37.03 de |

| B10 | 17.60 de | 15.5 e | 9.45 b | 33.52 bcd | 42.01 bcd | 21.22 d | 35.93 de |

| DMSH | 1.58 | 1.47 | 0.83 | 5.14 | 5.67 | 5.56 | 5.46 |

In root length (20.60) the maximum value with 1 t ha-1 and pink nodules (20.78) with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure was observed. But for white nodules (10.33) the maximum value was recorded in 3 t ha-1 mushroom compost. The highest colonization was with mushrooms in 2 t ha-1 (40.7%). 47.87% of vesicles was associated with poultry manure at 2 t ha-1 and 36.78% of arbuscules and 45.54% hyphae was attributed to chicken manure at the highest level (Table 5; Wu and Zou, 2010); however, the highest percentage of hyphae (48.56%) was observed with mushroom compost on 2 tha-1. These results show that organic fertilizers cause a positive response in broad bean, particularly poultry manure. López et al. (2001) mentioned that organic fertilizers are a viable option to replace or complement inorganic fertilization.

Principal component analysis

Main components 1 and 2 explained 51.42% of the original total variation (Figure 1). These percentages are desirable to reliably interpret the approximate correlations observed in the bi-plot (Sánchez et al., 1995; Pérez et al., 2014). In quadrant 1, there was positive correlation between yield (RG) with 100 seeds weight (P100S) and clean seeds (PSL), pods (NVP) and pod weight per plant (PVP), number and weight of stained seeds (NSM, PSM), greenness index (IV), plant height (AP) and floral knots (NNF). Treatments that interacted favorably with these variables were 3, 13 and 13 (RG 2.46, 2.63 and 2.23 t ha-1). These facts indicate that the increase in yield is mainly due to direct and indirect improvements on them; thus, breeding, generation, validation, validation and technology transfer should benefit these interactions (Perez et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Interrelationships between 40 treatments (in number) and 21 variables (in print). 1= San Pedro, without mycorrhiza and 1 ton of chicken manure; 2= San Pedro, without mycorrhiza and 2 tons of chicken manure; 3= San Pedro, without mycorrhiza and 3 tons of chicken manure, ..., 21 = Santiago, without mycorrhiza and 1 ton of chicken manure; 22= Santiago, without mycorrhiza and 2.0 tons of chicken manure; 23= Santiago, without mycorrhiza and 3 tons of chicken manure, ..., 40= Santiago, with mycorrhiza and 60N-60P-30K.

These results are similar to those from Neal and McVetty (1983) who concluded that 68.5 to 76.4% of the variability in seed yield is due to more pods per plant (Chaieb et al., 2011), seeds per pod (Alan and Geren, 2007) and 100 seeds weight (Baginsky et al., 2013). The colonization rate (% COL) was also correlated with root length (LRz), arbuscules percentages (% ARB), hyphae (% HIF), vesicles (% VES) and pink nodules (NDRs). This fact underlines that the application of mycorrhizae had a positive effect in both cultivars when chicken manure and mushroom is added at a dose of 3 t ha-1 (T13, T19, T33 and T39).

In the above context, T13 (San Pedro with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure and G. fasciculatum) and T19 (San Pedro with 3 t ha-1 mushroom compost and G. fasciculatum) significantly contributed to the improvement in floral knots (NNF, 15.8 and 16), plant height (AP, 121.33 and 123.43 cm), greenness index (IV, 52.90 and 52.66) and pods per plant (NVP, 25.93, 25.73); the first also did in weight of clean seed (PSL, 62.53 g) and 100 seeds weight (P100S, 301.83 g) and yield (RG 2.63 t ha-1). T19 interacted positively with root length (LRz, 27.03), white nodules (NDBI, 12.5), colonization (COL, 72.2%) and arbuscules (ARB 71.46%) but these effects did not increase its RG. Treatment 6 (San Pedro with 3 t ha-1 vermicompost) expressed the highest quality of clean seed. This fact is contradictory because in the presence of arbuscules there is higher efficiency nutrient absorption and symbiosis when there is available phosphorus, like chicken manure (Wu and Zou, 2010).

In other studies it was observed that with G. fasciculatum improved growth of Vitis vinifera L. and phosphorus content was 15 times higher than in control (Alarcón et al., 2001). Robles et al. (2013) reported an increase in root length of Agave angustifolia. The cv. Santiago with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure plus mycorrhizal improved pods weight per plant (PVP, 124.1), clean seeds (NSL, 32.63), weight of clean seeds (PSL, 62.4 g), grain yield (RG 2.4 t ha-1) and arbuscules percentage (73.3) and hyphae (84.4), higher values than those reported by Singh et al. (2013). These results are attributed to arbuscules are fungal structures haustorium type, that generate inside the cortical cells and contribute to increased capacity of absorption and utilization of nutrients by both participants in symbiosis (Alarcón and Ferrera, 2000). Hyphae provide increased absorption surface than root hairs and thus significantly increase the uptake of relatively immobile ions such as phosphate, copper and zinc. Rojas and Ortuño (2007) found a positive effect by inoculating mycorrhizal and adding chicken manure and vermicompost in vegetables (Manjarrez et al., 1999).

Conclusions

Mycorrhizal cv. San Pedro had a better response NNF, AP, IV, NVP, PVP, PSL, P100 S, RS,% COL, LRZ, NRs, NBs,% VES and ARB%. Chicken manure and compost mushroom with 3 t ha-1 contributed to a better phenotypic expression in most of the variables evaluated. The cv. San Pedro with 3.0 t ha-1 of chicken manure and mycorrhiza showed the best performance for AP, IV, NVP, PSL, P100S and RG (2.63 t ha-1). The cv. San Pedro with 3 t ha-1 compost and mycorrhizal mushroom originated COL higher percentage (72.2%) and ARB (71.46%), LRZ (27.07) and NDbi (12.5). The cv. Santiago with 3 t ha-1 of chicken manure and G. fasciculatum had the highest PVP (124.10), NSL (32.63), PSL (62.4 g), RG (2.4 t ha-1),% ARB (73.30) and% of hyphae (84.4).

Literatura citada

Alan, O. and Geren, H. 2007. Evaluation of heritability and correlation for seed yield components in Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.). Agron. J. 6(3):484-487. [ Links ]

Alarcón, A. y Ferrera, C. R. 1999. Manejo de micorriza arbuscular en sistemas de propagación de plantas frutícolas. Terra. 17(3):179-191. [ Links ]

Alarcón, A. y Ferrera, C. R. 2000. Biofertilizantes: importancia y utilización en la agricultura Agric. Téc. Méx. 26(2):91-203. [ Links ]

Alarcón, A.; González, CH. M. C.; Ferrera, C. R. and Villegas, M. A. 2001. Efectividad de Glomus fasciculatum y Glomus etunicatum en el crecimiento de plántulas de Vitis vinífera L. obtenidas por micropropagación. Terra. 19:29-35. [ Links ]

Álvarez, S. J.; Gómez, V. D. A.; León, M. N. S. y Gutiérrez, M. F. A. 2010. Manejo integrado de fertilizantes y abonos orgánicos en el cultivo de maíz. Agrociencia. 44(5):575-586. [ Links ]

Baginsky, C.; Silva, P.; Auza J. and Acebedo, E. 2013. Evaluation for fresh consumption of new broad bean genotypes with a determinate growth habit in central Chile. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 73(3):225-232. [ Links ]

Castro, A.; Henríquez, C. y Bertsch, F. 2009. Capacidad de suministro de N, P y K de cuatro abonos orgánicos. Rev. Agron. Costarricense. 33(1):31-43. [ Links ]

Chaieb, N.; Mohammed, B. and Mars, M. 2011. Growth and yield parameters variability among faba bean (Vicia faba L.) genotypes. J. Nat. Prod. Plant Res. 1(2):81-90. [ Links ]

Davies, Jr. F. T.; Olalde, P. V.; Aguilera, G. L.; Alvarado, M. J.; Ferrera, C. and Burton, T. W. 2002. Alleviation of drought stress of Chile ancho pepper (Capsicum annuum L. cv. San Luis) with arbuscular mycorrhiza indigenous to México. Sci. Hortic. (92):347-359. [ Links ]

Dutt, S.; Saharma, S. D. and Kumar, P. 2013. Arbuscular mycorrhizas and Zn fertilization modify growth and physiological behavior of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Sci. Hortic. 155:97-104. [ Links ]

Eghball, B.; Ginting, D. and Gilley, E. J. 2002. Residual effects of manure and compust application on corn producction and soil properties. Agron. J. 96:442-447. [ Links ]

FAOSTAT. 2013. Base de datos estadísticos de la FAO. http://www.faostat.fao.org/.site/567. [ Links ]

Gosling, P.; Hondge, A.; Goodlas, G. and Bending. G.D.2006. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and organic forming. Agric. Ecosys. Environ.113:17-35. [ Links ]

Hernández, W. y Salas, E. 2009. La inoculación con Glomus fasciculatum en el crecimiento de cuatro especies forestales en vivero y campo. Agron. Costarricence. 33(1):17-30. [ Links ]

Kalia, P. and Sood, S. 2004. Genetic variation association analyses for pod yield and other agronomic and quality characters in an Indian Himalayan collection of broad bean (Vicia faba L.). SABRAD. J. Breed. Genetics. 36(2):55-61. [ Links ]

López, M. J. D.; Díaz, E. A.; Martínez, R. E. y Valdez, C. R. D. 2001. Abonos orgánicos y su efecto en propiedades físicas y químicas del suelo y rendimiento de maíz. Terra. 19(4):293-299. [ Links ]

Manjarrez, M. M. J.; Ferrera, C. R. y González, Ch. M. C.1999. Efecto de la vermicomposta y la micorriza arbuscular en el desarrollo y tasa fotosintética de chile serrano. Terra. 17(1):9-15. [ Links ]

Mena, V. H. G.; Ocampo, J. O.; Dendooven, L.; Martínez, S. G.; González, C.J.; Davies, Jr. F. T. and Olalde, P. V. 2006. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance fruit growth and quality of chile ancho (Capsicum annuum L. cv. San Luis) plants exposed to drought. Mycorrhiza. 16:261-267. [ Links ]

Neal, J. R. and Mcvetty, P. B. E. 1983. Yield structure of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) grown in Manitoba. Field Crops Res. 8:349-360. [ Links ]

Orozco, M. y Thienhaus, S. 1997. Efecto de la gallinaza en plantaciones de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en desarrollo. Agron. Mesoam. 8(1):81-92. [ Links ]

Pérez, L. D. J.; González, H. A.; Franco, M. O.; Rubí, A. M.; Ramírez, D. J. F.; Castañeda, V. A. y Aquino, M. J. G. 2014. Aplicación de métodos multivariados para identificar cultivares sobresalientes de haba para el estado de México, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 5(2):264-279. [ Links ]

Philips, J. M. and Hayman, D. S. 1970. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular arbuscular micorrhizal fungi for rapid assesment of infection; transactions of the British Mycological Society. 55:158-161. [ Links ]

Pool, N. L.; Trinidad, S. A.; Etchevers, B. J. D.; Pérez, M. J. y Martínez, G. A. 2000. Mejoradores de la fertilidad del suelo en la agricultura de ladera de los Altos de Chiapas, México: Agrociencia 34: 251-259. [ Links ]

Rilling, M. and Mummey, D. I. 2006. Mycorrhizae and soil structure. New Phytologist 71:41-53. [ Links ]

Robles, M. M. L.; Robles, C.; Rivera B. F.; Ortega, L. M. L. y Pliego, M. L. 2013. Inoculación con consorcios nativos de hongos de micorriza arbuscular en Agave agustifolia Haw. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 6:1231-1240. [ Links ]

Rojas, R. K. y Ortuño, N. 2007. Evaluación de micorrizas arbusculares en interacción con abonos orgánicos como coadyuvantes del crecimiento en la producción hortícola del Valle Alto de Cochabamba, Bolivia. Acta Nova. 3(4):697-719. [ Links ]

Romero, L. M. D. R.; Trinidad, S. A.; Espinosa, G. R. y Ferrera, C. R. 2000. Producción de papa y biomasa microbiana en suelo con abonos orgánicos y minerales. Agrociencia 34:261-269. [ Links ]

Saif, S. R. 1986.Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in tropical foraje species as influenced by season, soil texture, fertilizers, host species and ecotypes. AGEW. Bot. 60:125-139. [ Links ]

Sánchez, G. J. J. 1995. El análisis biplot en clasificación. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 18:188-203. [ Links ]

SIAP. 2013. Cierre de la producción agrícola por estado. Producción nacional de haba para grano. http://www.siap.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Singh, R.; Soni, S. K. and Kaira, A. 2013. Synergy between Glomus fasciculatum and a beneficial Pseudomonas in reducing root diseases and improving yield and forskolin content in Coleus forskohlii Brinq, under organic field conditions. Mycorrhiza 23: 35- 44. [ Links ]

Smith, F. A. and Smith, S. E. 2011. What is the significance of the arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of many economically important crop plants? Plant Soil. 384:63-79. [ Links ]

Talaat, N. B. and Shawky, B. T. 2011. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on yield, nutrients, organic solutes, and antioxidant enzimes of two wheat cultivars under salt stress. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 174:283-291. [ Links ]

Thanuja, T. V.; Helde, R. V. and Screenivasa, M. N. 2002. Induction of rooting and root growth in black pepper cuttings (Piper nigrum L.) with the inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizae. Sci. Hortic. 92:339-346. [ Links ]

West, B.; Brandt, J.; Holstien, K.; Hill, A. and Hill, M. 2009. Fern-associated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are represented by multiple Glomus ssp.: do environmental factors influencepartner identity? Mycorrhiza. 19:295-304. [ Links ]

Wu, Q. S. and Zou, Y. N. 2010. Beneficial roles of arbuscular micorrhizas in citrus seedlings at temperatura strees. Sci. Hortic. 125:289-293. [ Links ]

Wu, Q. S. and Zou, Y. N.; Huang, Y. M.; Li, Y. and He, X. H. 2013. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce sucrose cleavage for carbon supply of arbuscular mycorrhizas in citrus genotypes. Sci. Hortic. 160:320-325. [ Links ]

Received: June 2016; Accepted: August 2016

text in

text in