Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 no.6 Texcoco Ago./Set. 2016

Articles

Effect of fire on production and quality of natal grass in Aguascalientes

1Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes-Centro de Ciencias Agropecuarias. Avenida Universidad Núm. 940, Col. Ciudad Universitaria, C. P. 20131, Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, México. (efancira@gmail.com; drhaubi@yahoo.com; adiazr@correo.uaa.mx; jjluna@correo.uaa.mx).

2Campo Experimental Vaquerías-INIFAP. Carretera Ojuelos-Lagos de Moreno km 8, Jalisco. (lunalm@yahoo.com.mx).

In Calvillo, Aguascalientes, Mexico, from 2012 and 2013, the effect of fire (burned Q and without burning SQ treatments) on production and nutritional quality of natal grass in three phenological stages was evaluated: growth C, maturity M, and latency L. The fire was applied in April 2012 to 16 m2 plots. During 2012 and 2013 forage production (dry basis) was different (p≤ 0.05) with 168.7, 393.7 g m2 and 53.9, 192.7 g m2 for Q and SQ treatments respectively. Crude protein was similar between treatments (p≥ 0.05) but different (p≤ 0.05) between C, M, L stages, with a total of 13.3, 5.2, 5.6% and 12.6, 4.6, 3.2% respectively. The digestibility of dry matter (DISMS) was different (p≤ 0.05) between treatments Q and SQ and between stages of C, M, and L, with a total of 61.6, 46.0, 48.3% and 50.3, 42.5, 44% respectively. Neutral detergent fiber (FDN) was different (p≤ 0.05) between stages C, M, and L, but not between Q and SQ with values 67.1, 76.5, 78% and 66.4, 76.3, 79.6% respectively. The acid detergent fiber (FDA) showed differences (p≤ 0.05) between stages but not between treatments with a total of 35.8, 50.6, 57.4%, and 33.2, 54.6, 56.3% respectively. The fire increased both production and quality of natal grass forage and could be used as a strategy for ecological management in areas of extensive grazing invaded with natal grass.

Keywords: Melinis repens; burning; fodder; nutritional value

En Calvillo, Aguascalientes, México, durante 2012 y 2013, se evaluó el efecto del fuego (tratamientos de quema Q y sin quema SQ) sobre la producción y calidad nutritiva del zacate rosado en tres etapas fenológicas: crecimiento C, madurez M, y latencia L. El fuego se aplicó en abril de 2012 a parcelas de 16 m2. Durante 2012 y 2013 la producción de forraje (base seca) fue diferente (p≤ 0.05) con 168.7, 393.7 g m2 y 53.9, 192.7 g m2 para los tratamientos Q y SQ respectivamente. La proteína cruda fue similar entre tratamientos (p≥ 0.05), pero diferente (p≤ 0.05) entre etapas C, M, L, con un total de 13.3, 5.2, 5.6% y 12.6, 4.6, 3.2% respectivamente. La digestibilidad de la materia seca (DISMS) resultó diferente (p≤ 0.05) entre tratamientos Q y SQ y entre las etapas de C, M, y L, con un total de 61.6, 46.0, 48.3% y 50.3, 42.5, 44% respectivamente. La fibra detergente neutro (FDN) resultó diferente (p≤ 0.05) entre las etapas C, M, y L, no así entre tratamientos Q y SQ con valores 67.1, 76.5, 78% y 66.4, 76.3, 79.6% respectivamente. La fibra detergente ácido (FDA) mostró diferencias (p≤ 0.05) entre etapas C, M, y L, más no entre tratamientos Q y SQ con un total de 35.8, 50.6, 57.4%, y 33.2, 54.6, 56.3% respectivamente. El fuego incrementó tanto la producción y calidad del forraje del zacate rosado y podría utilizarse como estrategia de manejo ecológica en áreas de pastoreo extensivo invadidas con zacate rosado.

Palabras clave: Melinis repens; forraje; quema; valor nutritivo

Introduction

Fire and grazing are considered as major disturbances in many pastures from the historical point of view and in the modern management of our era. Humans have used fire to manipulate and manage ecosystems (Bowman et al., 2009), while grazing contributes to the functioning and conservation of grasslands (Toombs et al., 2010; Allred et al., 2011). In fact, fire and grazing frequently operate as an interactive disturbance with different ecological effects of each other (Fuhlendorf et al., 2009), which creates heterogeneity in the structure of vegetation; important in the conservation of grasslands (Leis et al., 2013; McGranahan et al., 2013). Grasslands globally are vital not only for livestock but also as suppliers of an important number of goods and ecosystem services for society: as carbon sequestration, water infiltration, oxygen production, biodiversity, among others (Dinerstein et al., 2007).

Despite the importance of grasslands, one of the deterioration causes is the spread of exotic or invasive species that have displaced native species disrupting biodiversity and ecological balance (Enriquez and Quero, 2006). One of these species is natal grass Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, which is originally from South Africa (Bogdan, 1977). In Mexico, it is distributed in all states regardless of latitude, altitude, rainfall and soil (Davila et al., 2006; Stevens and Fehmi, 2009; Díaz et al., 2012; Flores, 2013; Melgoza et al., 2014).

In the state of Aguascalientes it is reported to be present in virtually all municipalities (Díaz et al., 2012). However, existing scientific information explaining the effect of fire both in production and quality of natal grass forage is very limited. This information is essential to determine management strategies that guide to achieve full utilization of this species. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the effect of fire on the production and quality of natal grass forage in the municipality of Calvillo, Aguascalientes, and in which our null hypothesis of interest was that there would be no effect of fire on productivity and quality of natal grass.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in during 2012 and 2013 in the town called Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes, in an abandoned agricultural land with an area of 2 ha, and totally invaded of natal grass. Its geographical position is located between 21° 47' 31" and 102° 43' 9" north latitude, at an average altitude of 1 780 masl. The climate of the region is temperate sub-humid (García, 1988; Medina et al., 1998) with an average annual temperature of 20 °C and shallow, rocky soils and poor in organic matter Regosol and Feozem type (INIFAP, 1998). Rainfall is mainly present from June to September, which in 2012 and 2013 had an annual average of 640 and 768 mm respectively (Figure 1).

Within the experimental area 10 plots of 16 m2 (4 x 4 m) were distributed randomly, of which five were subjected to burning (Q) and the other five were considered as control since these were not burned (SQ). To the latter (SQ), were removed the accumulated dry forage from years at ground level with the help of scissors Corona brand. Burning was carried out on April 1st 2012 using a drip torch Sure Seal® with 10 liters capacity, with a petrol ratio: diesel 6: 4. It was set at 7:00 h at an atmospheric temperature of 16 °C, a relative humidity of 35%, wind speed which ranged between 3 and 4 km h-1 and an average of 479.4 g m-2 of dry matter (combustible). To minimize the risk of fire escape to neighboring areas, mineral lines were traced around the plots and its perimeter was moistened with water using a backpack sprayer with 20 L capacity. Forage production on a dry basis was evaluated at peak of production which was at the end of October 2012 and 2013, through 5 quadrants of 0.5 m2 plot (n= 50) by removing in each of them the forage at ground level, same that was dehydrated in a dryer herbarium at a temperature of 60 °C for 10 days and weighed with a digital scale OHAUS® with 20 kg capacity.

Forage quality was evaluated by a total of 10 composite samples (n= 10), five burned and five in the control area, with a weight of 1kg/plot. Forage samplings were carried out in three phenological stages: growth (C), maturity (M) and latency (L), for a total of 30 samples (n= 30) in burned (Q) and without burning (SQ) areas.

For C stage forage was harvested in early July; m at the end of September 2012; while L in mid-February 2013. The samples were processed at the Laboratory of Animal Nutrition Center of Agricultural Sciences at the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes (UAA), with a mill Wiley® and 1 mm mesh, and stored in plastic containers until chemical analyzes of crude protein (PC), neutral detergent fiber (FDN) and acid detergent fiber (FDA) were performed, based on the procedures to estimate nutritional content in forages (Tejada, 1985). In situ ruminal digestibility of dry matter (DISMS) was performed according to the nylon bag method (Mehrez and Ørskov, 1977). Using a fistulated cow rumen Holstein breed with maintenance diet and residence time of the food sample in rumen for 48 hours.

Data was subjected to analysis of variance with the lineal general model (GLM) considering a completely randomized design in factorial arrangement 2 x 2 for the production of dry matter: 2 fire treatments (Q and SQ) and 2 years (2012 and 2013). For nutritional quality was used another factorial design 2 x 3: 2 fire treatments (Q and SQ) and 3 phenological stages (C, M and L) (SAS, 2001). When there were differences between treatments Tukey test was used (p≤ 0.05) for mean separation (Steel and Torrie, 1980).

Results and discussion

The results of this experiment of burning rejects the null hypothesis that burning would not have effect on either productivity or quality on natal grass forage. Total production of forage on dry basis was different (p≤ 0.05) between treatments Q and SQ, and between years. There was higher production on burned areas with 168.7 and 393.7 g m-2, while in without burning production was 53.9 and 192.7 g m-2, in 2012 and 2013 respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forage production on dry matter basis of natal grass Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, in Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes during 2012 and 2013.

These results agree with those reported by several authors concluding that the differences in forage production on dry basis are due to chemical effects of the combustion of plant material on the ground, provides various nutrients, primarily nitrogen, which is left available favoring vegetative reproduction, coupled with the presence of higher temperatures in burned areas during the day and vapor condensation during the night, creating near the dewpoint conditions and making available the nutrients released during combustion (Wright and Bailey, 1982; Frost and Robertson, 1987; Briske and Richards, 1994).

Other authors mention that the increase in forage production is because after burning, nutrients are immediately released and available to plants from the ashes, mainly minerals (Sacido and Cauhépé, 1993; Bates et al., 2009). Riser and Parton (1982), ruled considerable increases in forage production in tallgrass prairie US after burning, through its effects on temporal pattern of nitrogen and carbon in the soil and the availability of light for photosynthesis. Johnson and Mitchett (2001) concluded that herbaceous plants that serve as food for wildlife were ten times more abundant in areas where prescribed burning was applied than in unburned areas.

The increase in plant nutrients have been reported in the first growing season after spring burnings in temperate environments (Bennett et al., 2002). In general, the use of fire in grassland ecosystems favors various benefits, including increased forage production of native grasses (McIlvain and Armstrong, 1968; Sharrow and Wright, 1977; Scifres and Hamilton, 1993). Fire decreased forage production in the first year of implementation in grasslands from Chihuahua, but increased in subsequent years with good grazing management (Sierra et al., 2008).

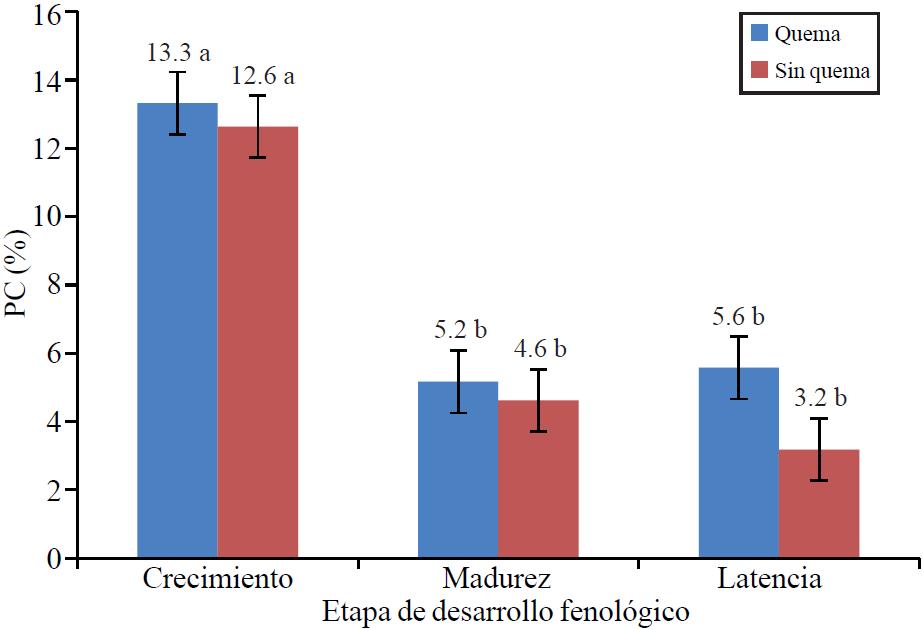

Crude protein showed no significant differences (p≥ 0.05) between Q and SQ treatments, but was different (p≤ 0.05) between phenological stages (C, M, and L) (Figure 3). Crude protein values for burned areas were 13.3, 5.2 and 5.6% against 12.6, 4.6, and 3.2% for unburned areas in C, M and L stages respectively.

Figure 3. Average ratio of crude protein (CP) in forage Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, burned and unburned in Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes, 2012-2013.

These results are consistent with those from Leland et al. (1976), who found that crude protein of Andropogon scoparius (Michx.) a C4 grass like Melinis repens was higher in burned areas than unburned.

Sanderson and Wedin (1989) stated that crude protein content in summer grass (C4) was higher in summer and lower during latency. This coincides with Chávez and González (2008), who found in native grasses a maximum content of crude protein in summer, which decreased in the fall, and even more in the winter, recovering in early spring in areas without burning. Meanwhile Krysl et al. (1987) found that the crude protein ranged between 15.4 and 9.6% for growth and latency stages respectively, in blue grama in New Mexico.

McGranhan et al. (2014) noted significant increases of up to 4% in crude protein content in burned areas of Andropogon virginicus L., compared to unburned in Tennessee. Generally crude protein content in forages is necessary to meet the needs of rumen microorganisms to digest fiber which is around 7%, without affecting their voluntary intake, suggesting the need for protein supplementation when forage has values lower than 7%, thereby increasing voluntary forage intake (Pitts et al., 1992).

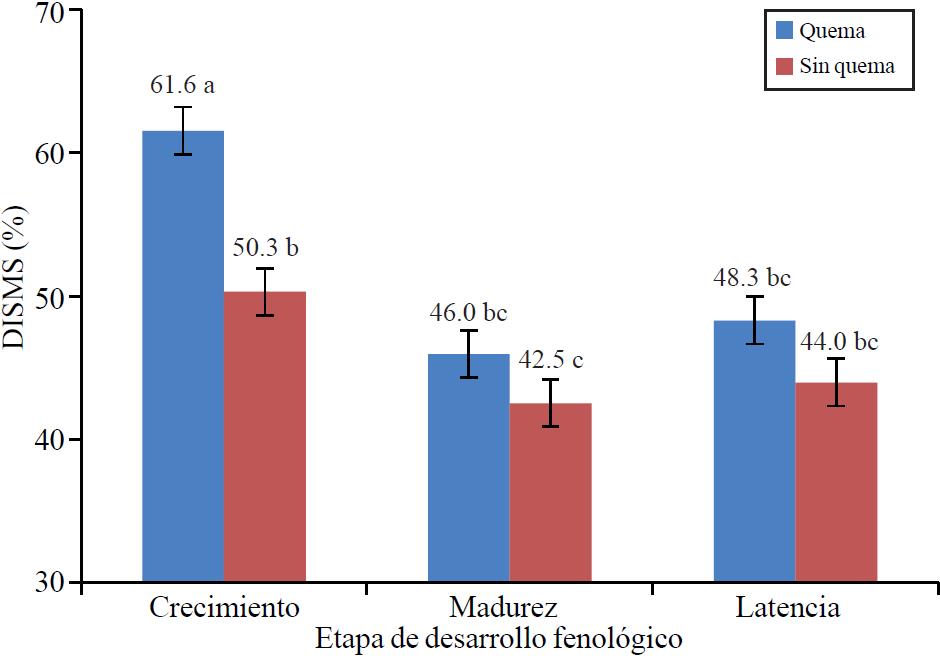

In situ digestibility of dry matter (DISMS) at 48 hours was different (p≤ 0.05) between Q and SQ treatments and phenological stages C, M and L (Figure 4).

Figure 4. In situ average digestibility of dry matter (DISMS) at 48 h in Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, burned and unburned in Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes, 2012-2013.

Overall DISMS decreased (p≤ 0.05) as natal grass maturity advances both in Q and SQ treatments, although this reduction is more marked in SQ treatment with a total of 61.6, 46; and 48.3% and 50.3, 42.5, 44% respectively in the three phenological stages C, M, L. Krysl et al. (1987) in blue grama Bouteloua gracilis (Willd. Ex Kunth) Lag. ex Griffiths., in New Mexico reached similar results by pointing out that DISMS declined as forage maturity advances 61.8% during growth to 47.9% in latency, this concomitant increase in fiber fractions in forage (fiber acid and neutral detergent) in unburned areas.

Smith et al. (1960), for Andropogon scoparius (Michx.) found DISMS values ranging between 40.3 to 65.7% in unburned and burned plots respectively. In humid savannas from Cameroon, Klop et al. (2007) concluded that grass DISMS of unburned and burned areas ranged from 50.2 to 57.1% respectively. Núñez (1971) worked in unburned areas of native grasslands in Chihuahua finding that the percentages of DISMS fluctuated between 31.6 and 40.2% at the beginning of the growth stage and 43.3 and 49.5% at the end of it. Villanueva et al. (1989) reports that this fluctuation pattern in DISMS and other nutritional components of forage is common in native grasses from arid and semiarid areas of Mexico contrasting areas subject to burning and those not subject to it.

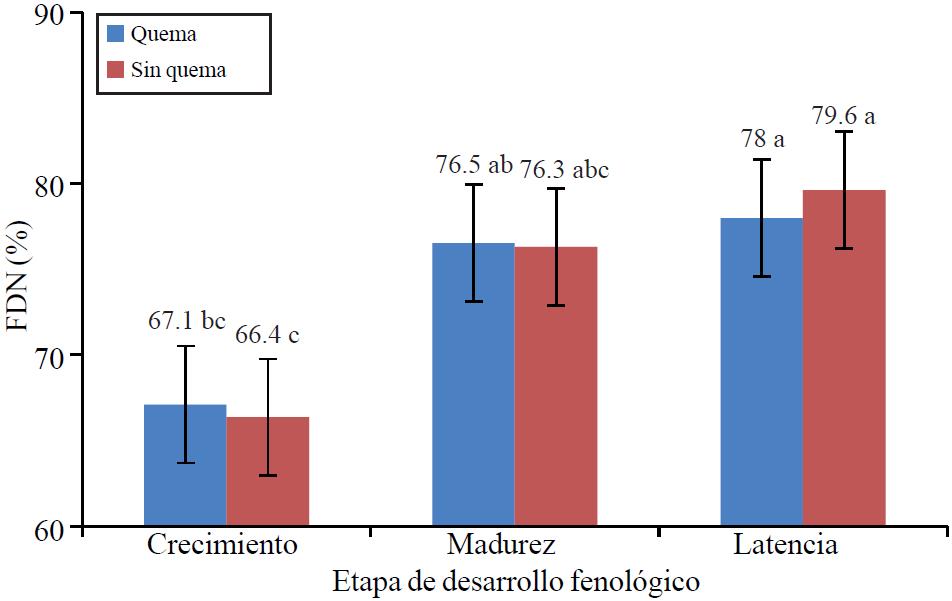

Neutral detergent fiber (FDN) represents most of the material contained in the cell walls of the available forage in the diet and is composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Holechek et al., 2011). Our results show generally a significant increase (p≤ 0.05) in FDN content as natal grass maturity advances, but not between Q and SQ treatments (p≥ 0.05) (Figure 5). Data related with FDN were different (p≤ 0.05) among the three phenological stages under study (C, M, L) with a total of 67.1, 76.5, 78%; and 66.4, 76.3, and 79.6% in treatments with Q and SQ respectively.

Figure 5. Average ratio of neutral detergent fiber (FDN) in forage Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, burned and unburned in Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes, 2012- 2013.

This agrees with Ulyatt (1980) and Van Soest (1982), who widely determined that the contents of FDN in forage increases as maturity advances. Krysl et al. (1987) concluded that FDN in grassland forage from New Mexico fluctuated slightly from 77.4% to 75.8% between growing seasons and latency respectively in areas without burning. In central grasslands from Chihuahua, Chávez et al. (1984), found FDN values ranging between 72.1 and 76.5% in native grasses during growing season, while Ortega et al. (1984), obtained FDN content in fodder shrubs consumed by goats in central Chihuahua ranging between 33.9 and 38.3% in unburned areas.

FDA fraction contains the most resistant substances to ruminal degradation contained in the cell wall (cellulose, lignin and silica) (Holechek et al., 2011). Our results show generally a significant increase (p≤ 0.05) in FDA content as natal grass maturity advances, but not between treatments Q and SQ (p≥ 0.05) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Average ratio of acid detergent fiber (FDA) in forage Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, burned and unburned in Mesa Grande, Calvillo, Aguascalientes, 2012- 2013.

Data related to FDA were different between growth stages (C, M and L) with a total of 35.8, 50.6, 57.4%; and 33.2, 54.7; and 56.3% in Q and SQ respectively. FDA increased as natal grass maturity advances. In central grasslands of Chihuahua, Chávez et al. (1984), found FDA values ranging between 45.6 and 50.7% in native grasses during growing season, while Ortega et al. (1984), obtained FDA contents in fodder shrubs consumed by goats in central Chihuahua ranging between 28.9 and 31.6% in unburned areas.

Is possible to achieve increases in forage quality using prescribed burning by the effect of improving nutrient availability in some soil elements (Wright and Bailey, 1982; Knapp and Seastedt, 1986; Ojima et al., 1990; García, 1992); this is due to mineralization and fixing of the same (Hobbs et al., 1991), in the first five centimeters of soil (Haubensak et al., 2009). Short et al. (1974) concluded that the FDN in native forages is generally always greater than the FDA.

Conclusion

Overall can be concluded that burning Natal grass forage had a positive effect on improving its production and quality, therefore fire as management strategy could be used to exploit this species in areas where its presence is constantly growing and considered a threat to be an invasive species that rapidly and practically establishes in any soil. This kind of work opens the option of using prescribed burning as management strategy of grassland for optimal and comprehensive management of rangelands with presence of Melinis repens and increase its productivity and quality, besides to achieve increases in voluntary consumption from animals used under extensive conditions this type of forage.

Literatura citada

Allred, B. W.; Fuhlendorf, S. D. and Hamilton R. G. 2011. The role of herbivores in great plains conservation: comparative ecology of bison and cattle. Ecosphere 2:26. [ Links ]

Bates, J. D.; Rhodes, E. C.; Davies, K. W. and Sharp, R. 2009. Post fire succession in big sagebrush steppe with livestock grazing. Rangeland Ecol. Manag. 62:98-110. [ Links ]

Bennett, L. T.; Judd, T. S. and Adams, M. A. 2002. Growth and elemental content of perennial grasslands following burning in semiarid, subtropical Australia. Plant Ecol. 164:185-199. [ Links ]

Bogdan, A. V. 1977. Tropical pasture and fodder plants (grasses and legumes). Longman group (far east). Limited. 475 p. [ Links ]

Bowman, D. M. J. S.; Balch, J. K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W. J.; Carlson, J. M.; Cochrane, M. A.; D’Antonio, C. M.; Defries, R. S.; Doyle, J. C.; Harrison, S. P.; Johnston, F. H.; Keeley, J. E.; Krawchuk, M. A.; Kull, C. A.; Marston, J. B.; Moritz, M. A.; Prentice, I. C.; Roos, C. I.; Scott, A.C.; Swetnam, T. W.; van der Werf, J. R. and Pyne, S. J. 2009. Fire in the earth system. Science. 324:481-484. [ Links ]

Briske, D. D. and Richards, J. H. 1994. Physiological responses of individual plants to grazing: current status and ecological significance. In: ecological implications of livestock herbivory in the West. Vavra, M.; Laycock, W. A. and Pieper, R. D. (Eds.). 1st (Ed). Society for Range Management. Denver, Colorado. 147-176 pp. [ Links ]

Caton, J. S.; Freeman, A. S. and Galyean, M. L. 1988. Influence of protein supplementation on forage intake, in situ forage disappearance, ruminal fermentation and digesta passage rates in steers grazing dormant blue grama rangeland. J. An. Sci. 66:2262-2271. [ Links ]

Chávez, S. A. H. y González, G. F. J. 2008. Estudios Zootécnicos I-Animales en Pastoreo. In: Chávez, S. A. H. (Comp.). Rancho Experimental La Campana 50 Años de Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología en Pastizales y Producción Animal. INIFAP- Centro de Investigación Regional Norte-Centro. Sitio Experimental La Campana-Madera. Libro técnico Núm. 2. 214 p. [ Links ]

Dávila, P.; Mejía, S. M.T.; Gómez, S. J. M.; Valdés, R. J. J.; Ortiz, C.; Morín, C. J. y Ocampo A. 2006. Catálogo de las gramíneas de México. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM)- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). 1a (Ed.). 671 p. [ Links ]

Díaz, R. A.; Flores A. E.; de Luna, J. A.; Luna J. J.; Frías, H. J. T y Olalde, P. V. 2012. Biomasa aérea, cantidad y calidad de semilla de Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, en Aguascalientes, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 3(1):33-47. [ Links ]

Dinerstein, E.; Olson, D.; Atchley, J.; Loucks C.; Contreras, S.; Abell, R.; Iñigo, E.; Enkerlin, E.; Enríquez, C. Q. J. F. y Quero, C. A. R. 2007. Reseña de la producción y suministro de semilla de especies forrajeras en México. In: Velazco, Z. M. E.; Hernández, G. A.; Pérezgrovas, R. y Sánchez, M. B. Producción y manejo de los recursos forrajeros tropicales. Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas (UACH). Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas. 217-237 pp. [ Links ]

Chávez, S. A. H.; Villalobos, E. y Máynes, M. 1984. Contenido y fluctuación de nutrientes de especies nativas consumidas por el ganado en los agostaderos de Chihuahua. Boletín Pastizales RELC-INIP-SARH. 15(1):24-27. [ Links ]

Enríquez. J. F. y Quero, C. A. E. 2006. Producción de semilla de gramíneas y leguminosas forrajeras tropicales. INIFAP-Centro de Investigación Regional Golfo-Centro. Campo Experimental Papaloapan, Veracruz, México. Libro técnico Núm. 11. 109 p. [ Links ]

Flores, A. E. 2013. Pasto rosado Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka. In: Quero, C. A. R. (Ed.). Gramíneas introducidas: importancia e impacto en ecosistemas ganaderos. Biblioteca Básica de Agricultura (BBA) 1a (Ed.). Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 61-72 pp. [ Links ]

Frost, P. G. H. and Robertson, F. 1987. The ecological effects of fire in savannas. In: Walker, B. H. (Ed.). Determinants of tropical savannas, Oxford Press. ISBN: 1-85221-017-6. 289 p. [ Links ]

Fuhlendorf, S. D.; Engle, D. M.; Kerby J. and Hamilton, R. 2009. Pyric herbivory: rebuilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conserv. Biol. 23:588-598. [ Links ]

García, E. 1988. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köeppen. Instituto Nacional de Geografía. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). 217 p. [ Links ]

García, F. O. 1992. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics and microbial ecology in tallgrass prairie. Ph. D. Dissertation. Kansas State University. Manhattan Kansas. 189 p. [ Links ]

Haubensak, K.; D’Antonio, C. and Wixon, D. 2009. Effects of fire and environmental variables on plant structure and composition in grazed salt desert shrublands of the Great Basin (USA). J. Arid Environ. 73:643-650. [ Links ]

Hobbs, N. T.; Schimel D. S.; Owensby C. E. and Ojima, D. J. 1991. Fire and grazing in tallgrass prairie: contingent effects of nitrogen budgets. Ecology. 72:1374-1382. [ Links ]

Holechek, J. L.; Pieper R. D. and Herbel, C. H. 2011. Range management-principles and practices. 6th (Ed). Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. 444 p. [ Links ]

INIFAP. 1998. Guía para la asistencia técnica agrícola-área de Influencia del Campo Experimental Pabellón. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Rural (SAGARPA). Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Centro de Investigación Regional Norte Centro. Campo Experimental Pabellón. Aguascalientes, México. 429 p. [ Links ]

Johnson, L. C. and Mitchett, J. R. 2001. Fire and grazing regulate belowground processes in Tallgrass Prairie. Ecology. 82(12):3377-3389. [ Links ]

Klop, E.; van Goethem, J. and de Long, H. H. 2007. Resource selection by grazing herbivores on post-fire regrowth in a West African woodland savannah. Wildlife Res. 34(2):77-83. [ Links ]

Knapp, M. and Seastedt, J. 1986. Detritus accumulation limits productivity of tallgrass prairie. Biosci. 36:662-668. [ Links ]

Krysl, J. L.; Galyean M. L.; Wallace, J. D.; McCollum, F. T.; Judkins, M. B.; Branine, M. E. and Caton, J. S. 1987. Cattle Nutrition on blue grama rangeland in New Mexico. Agricultural Experiment Station. Bull. 727. New Mexico State University. College of Agriculture and Home Economics. 33 p. [ Links ]

Leland, J. A., Harbers, L. H.; Schalles, R. R.; Owensby C. E. and Smith, E. F. 1976. Range burning and fertilizing related nutritive value of bluestem grass. J. Range Manag. 29:306-308. [ Links ]

Leis, S. A.; Morrison, L. W. and Debacker, M. D. 2013. Spatiotemporal variation in vegetation structure resulting from pyric-herbivory. Prairie Naturalist. 45:13-20. [ Links ]

McIlvain, E. H. and Armstrong, C. G. 1968. Progress in range research. Woodward Brief 542. Woodward, Oklahoma. 135 p. [ Links ]

McGranahan, D. A.; Engle, D. M.; Fuhlendorf, S. D.; Winter, S. L.; Miller, J. R. and Debinski, D. M. 2013. Inconsistent outcomes of heterogeneity-based management underscore importance of matching evaluation to conservation objectives. Environ. Sci. Policy. 31:53-60. [ Links ]

McGranahan, D. A.; Henderson, Ch. B.; Hill, J. S.; Raicovich, G. M.; Wilson, W. N. and Smith, C. K. 2014. Patch burning improves forage quality and creates grass-bank in old-field pasture: results of a demonstration trial. Southeastern Naturalist. 13(2):200-207. [ Links ]

Medina, G. G.; Ruiz, C. J. A. y Martínez, P. R. A. 1998. Los climas de México. 1998. Una estratificación ambiental basada en el componente climático. Centro de Investigación Regional del Pacífico Norte. INIFAP- SAGAR. Libro técnico No. 1. 103 p. [ Links ]

Mehrez, A. Z. and Ørskov, E. R. 1977. A study of the artificial fibre bag technique for determining the digestibility of feeds in the rumen. J. Agric. Sci. 88(3):645-650. [ Links ]

Melgoza, C. A.; Balandrán, M. I.; Mata, V. R. y Pinedo, G. C. A. 2014. Biología del pasto rosado Melinis repens (Willd.) e implicaciones para su aprovechamiento o control. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 5(4):429-442. [ Links ]

Núñez, G. F. 1971. Digestibilidad in situ de algunos zacates nativos del centro de Chihuahua. Boletín Pastizales. RELC-INIP-SAG. 3(2):8-11. [ Links ]

Ojima, D. S.; Parton, W. J.; Schimel, D. S. and Owensby, C. E. 1990. Simulated impacts of annual burning on prairie ecosystems. In: fire in North American tallgrass prairies. Collins, S. L. and Wallace, L. L. (Eds.). University of Oklahoma Press. Norman, Oklahoma. 175 p. [ Links ]

Ortega, R. L.; Chávez, S. A. y Fierro, G. L. C. 1984. Valor nutricional de las principales especies forrajeras consumidas por caprinos en la parte central de Chihuahua. Boletín Pastizales-RELC-INIP-SAG. 16(1):11-22. [ Links ]

Pitts, J. S.; McCollum, F. T. and Britton, C. M. 1992. Protein supplementation of steers grazing tobosa grass in Spring and Summer. J. Range Manag. 45:226-231. [ Links ]

Risser, P. G. and Parton, W. J. 1982. Ecosystem analysis of the tallgrass prairie: nitrogen cycle. Ecology. 63:1342-1351. [ Links ]

Sacido, M. y Cauhépé, M. A. 1993. Uso del fuego en pastizales: efecto sobre la calidad de los rebrotes. In: Kunst, C. R.; Sipowicz, A. H.; Maceira, N. O. y Bravo, de M. S. (Eds.). Memoria de Seminario- Taller: Ecología y Manejo del Fuego en Ecosistemas Naturales y Modificados. Programa de Recursos Vegetales Naturales y Fauna Silvestre. INTA- Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Buenos Aires y Santiago del Estero, Argentina. 243 p. [ Links ]

Sanderson, M. A. and Wedin, W. F. 1989. Phenological stage and herbage quality relationships in temperate grasses and legumes. Agron. J. 81:864-869. [ Links ]

SAS. 2001. SAS User´s Guide: Statistics version 8 (Ed.). SAS Inst. Inc. Cary, NC,USA. [ Links ]

Scifres, C. J. and Hamilton, W. T. 1993. Prescribed burning for brushland management: the south Texas example. College Station, Texas. Texas A&M University Press. 246 p. [ Links ]

Sharrow, S. H. and Wright, H. A. 1977. Proper burning intervals for tobosa grass in east Texas based on nitrogen dynamics. J. Range Manag. 30:343-346. [ Links ]

Short, H. L.; Blair, R. M. and Segelquist, Ch. A. 1974. Forage composition and forage digestibility by small ruminants. J. Wildlife Manag. 38(2):197-209. [ Links ]

Sierra, T. J. S.; Saucedo, T. R.; Lara, M. C. R.; Jurado, G. P. y Morales, N. C. R. 2008. Manejo y Aprovechamiento de la Vegetación. In: Chávez, S. A. H. (Comp.). Rancho Experimental La Campana 50 Años de Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología en Pastizales y Producción Animal. INIFAP- Centro de Investigación Regional Norte-Centro. Sitio Experimental La Campana- Madera. Libro técnico Núm. 2. 214 p. [ Links ]

Smith, E. F.; Young, V. A.; Anderson, K. L.; Ruliffson, W. S. and Rogers, S. N. 1960. The digestibility of forage on burned and non-burned bluestem pasture as determined with grazing animals. J. Animal Sci. 19(2):388-391. [ Links ]

Steel, R. G. D. and Torrie, J. H. 1980. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biometrical approach. 2nd (Ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Co. New York. 633 p. [ Links ]

Stevens, J. M. and Fehmi, J. S. 2009. Competitive effect of two nonnative grasses on a native grass in southern Arizona. Invasive Plant Science Management. 2(4):379-385. [ Links ]

Tejada, H. I. 1985. Manual de laboratorio para análisis de ingredientes utilizados en la alimentación animal. Patronato de Apoyo a la Investigación y Experimentación Pecuaria de México. México, D. F. 387 p. [ Links ]

Toombs, T. P.; Derner, J. D.; Augustine, D. J.; Krueger, B. and Gallagher, S. 2010. Managing for biodiversity and livestock. Rangelands. 32:10-15. [ Links ]

Ulyatt, M. J. 1980. The feeding value of temperate pastures. In: Morley, F. H. W. (Ed.). Grazing animals. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co. New York. 125-142 pp. [ Links ]

Van Soest, P. J. 1982. Nutritional ecology of ruminant. O and B books, Corvallis, Oregon. 373p. [ Links ]

Villanueva, A. J. F.; Mena, H. L.; Herrera, I. R. y Negrete, R. L. F. 1989. Contenido y fluctuación nutricional de cinco gramíneas en trópico seco de acuerdo a su fenología. Revista Manejo de Pastizales. 2(2):21-25. [ Links ]

Wright, H. A. and Bailey, A. W. 1982. Fire ecology: United States and Canada. A Wiley-Interscience Publication. John Wiley and Sons. New York. 501 p. [ Links ]

Received: March 2016; Accepted: June 2016

texto em

texto em