Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 no.4 Texcoco may./jun. 2016

Articles

The Tetranychus urticae Koch effect on the quality of the flower stem of 15 rose cultivars

1 Centro Universitario UAEM Tenancingo. Carretera Tenancingo-Villa Guerrero, km 1.5, Estado de México, México, C. P. 52400. (gavago@hotmail.com; psb_ceci@yahoo.com.mx; soteromex@hotmail.com; lmvazquezg@uaemex.mx).

2 Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados en Fitomejoramiento, Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Carretera Toluca-Tlachaloya km 16. Campus Universitario “El Cerrillo”, Toluca, Estado de México, México. C. P. 50000. (agonzalezh@uaemex.mx).

The intensive cultivation rose (Rosa x hibrida) in Tenancingo and Villa Guerrero, State of Mexico, Mexico, it is significantly affected by Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), known as red spider. The objective of this research was to determine the tolerance to attack red spider and its effect on the quality of the floral stem 15 rose cultivars. Vegetative buds of the aforementioned cultivars grafted in the pattern Manettii (Rosa sp.) were established in pots in a greenhouse. The plants were infested with the mite when the flower bud reached 10 cm, then make weekly counts and evaluate the plant cutoff. Three experiments conducted in spring 2010, autumn 2010 and spring 2012, the number of mites per plant and six variables associated with quality floral stalk were evaluated. The results showed differential tolerance among cultivars; the ratchet variety was less tolerant and showed 3 times mites ambiance, the more resistant. Mite infestation was significantly correlated with number of petals, number of productive stems and stem diameter. The leaf area and chlorophyll content were not decisive in the preference of mites, perhaps were intrinsic variations among cultivars as total phenol content.

Keywords: floriculture area of the state of Mexico; flower production cycles; multivariate analysis; Rosa x hibrida cultivars; Valles Altos of Mexico Center

El cultivo intensivo de rosa (Rosa x hibrida) en Tenancingo y Villa Guerrero, Estado de México, México, es afectado significativamente por Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), conocida como araña roja. El objetivo de esta investigación fue determinar la tolerancia al ataque de araña roja y su efecto en la calidad del tallo floral de 15 cultivares de rosa. Yemas vegetativas de los cultivares mencionados, injertadas en el patrón Manettii (Rosa sp.) fueron establecidas en macetas bajo invernadero. Las plantas fueron infestadas con el ácaro cuando el brote floral alcanzó 10 cm de altura, para después hacer conteos semanales y evaluar la planta en punto de corte. De tres experimentos realizados en primavera de 2010, otoño de 2010 y primavera de 2012, se evaluaron número de ácaros por planta y seis variables asociadas a calidad del tallo floral. Los resultados mostraron tolerancia diferencial entre cultivares; la variedad catalina fue la menos tolerante y mostró 3 veces más ácaros que ambiance, la más resistente. La infestación del ácaro se correlacionó significativamente con número de pétalos, número de tallos productivos y diámetro de tallo. Área foliar y contenido de clorofila no fueron determinantes en la preferencia de los ácaros, quizás lo fueron variaciones intrínsecas entre cultivares como contenido de fenoles totales.

Palabras clave: análisis multivariados; ciclos de producción de flor; cultivares de Rosa x hibrida; Valles Altos del Centro de México; zona florícola del estado de México

Introduction

In Tenancingo and Villa Guerrero, State of Mexico, Mexico, the rose cut flower, with more than 100 different cultivars, occurs under plastic covers 683 ha (SIAP, 2010) and is only surpassed by gladiolus (Gladiolus grandiflorus Hort. ) and chrysanthemum (Dendranthema spp.). Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) (Kheradpir et al., 2007), known in the region as red spider, is one of the most important pests rose whose control in recent decades (Nyalala et al., 2013) it has complicated and expensive due to the resistance to acaricides (Flores et al., 2007). Therefore the identification of natural mechanisms for control is desirable. In Tenancingo and Villa Guerrero has been observed natural variation in tolerance of cultivars rose to pests and diseases (Martin et al., 2001; Khatun et al., 2009; Coruh y Ercisli, 2010; Flores et al., 2011), so that the identification of outstanding cultivars is essential to start breeding programs or generation and / or application of technology. The objective of this research was to determine the tolerance to attack red spider and its effect on the quality of the floral stem 15 rose cultivars.

Materials and methods

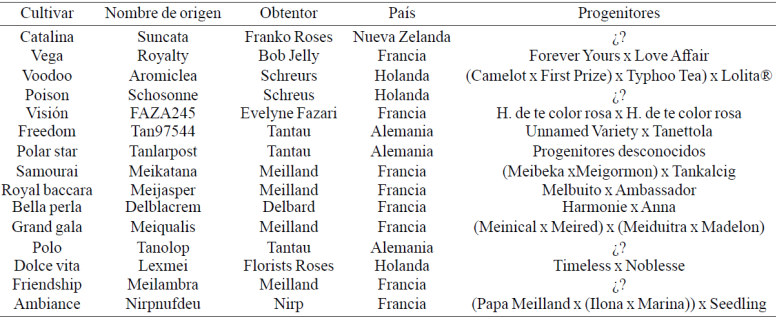

The research was done in greenhouses Tenancingo UAEM University Center of the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, located at 18º 97 '03'' north latitude and 99º 61' 17'' west longitude and altitude 2 200 m. Chosen according to previous work on perception of producers rose tolerance to pests and diseases 15 cultivars hybrid tea Rosa x hibrida were evaluated (Table 1; Anonymous 1 s.a; Anonymous 2 s.a).

The 15 cultivars were evaluated in spring 2010 and 2012 and fall 2010. The stems rooted pattern Manettii (Rosa sp.) Graft yolk evaluated cultivars were established individually greenhouse in black plastic pots of 14 L capacity in agricultural land, tepojal and germinaza (3:1:1) in a completely randomized design with eight repetitions. The pH measured with Nie-co. nieuwkoop b.v. aalsmeer, Holland, was adjusted to 6.4 with the addition of 120 g m-2 agricultural lime for the first cycle and 100 g m-2 for the following two. The electrical conductivity measured with HI 98130, Hanna, was adjusted from 0.3 to 2.1 deciSiemens cm-1 with the addition of fertilizer. The fertilization took 26-12-12+2MgO and microelements (Polyfeed Haifa Chemicals, Israel) one week after clamping applications 100 g m-2 every 15 days. Irrigation was applied twice weekly in spring and three times a week in autumn (60% moisture in the substrate).

Each plant the first flower bud was removed to induce multiple shooting and then leave two stems trimmed to 20 cm on average. The infestation is made 20 days after pruning when new flowering stems were 10 cm and consisted of depositing five mite T. urticae Koch mobility without sexing extracted from boxes increase in healthy host plants bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Mites were placed in the beam of the first basal leaf and from the infestation until the third sampling (24 days) temperature (°C) and daily relative humidity (%) was recorded with a higrotermógrafo (EL-USB-2 - RH/Temperature Data Logger, LASCAR electronics).

Weekly mite counts were performed on three occasion’s variety, starting a week of infestation, defined by the number of mobile mites per plant (NA). In order to observe effects of the infestation and damage of mites in the phenology of the plant, at the stage of "breakpoint" stem length were measured (LT, measured from its base to the apex of the flower bud), diameter stem (DT, average basal diameters, middle and apical stem), number of leaflets (NF, all stem leaves), petals flower bud (NP), productive stems (TP, with the presence of flower bud ) and blind stems (TC, which failed to flower differentiation).

Additionally leaf area was measured (AF, average size (cm2) leaves three stems; Portable Area Meter, Model L-3000A, and accessory L1-3050A/4, both LI-COR, USA) and chlorophyll levels in leaves damage (CCD) without damage (CSD) mite, measures SPAD units (Chlorophyll Meter, Spad- 502, Konica Minolta, Japan). With data combined variance analysis and comparison of means with the Tukey test (α= 0.05) was performed. In six of the cultivars, selected by their means and ends in incidence of mites values measured in three phenological stages the total phenol content (mg total phenol g-1 dry weight) by the Folin and Ciocalteu (Makkar et al., 2007). There was also a principal component analysis among cultivars and evaluated variables (González et al., 2010) and cluster analysis to define the group of cultivars according to their variables. The outputs were obtained with the Statistical Analysis System (Statistical Analysis System, SAS) version 9 for Windows, and biplot graphs and conglomerates were obtained with Info Stat Version 2008.

Results and discussion

Degree of infestation

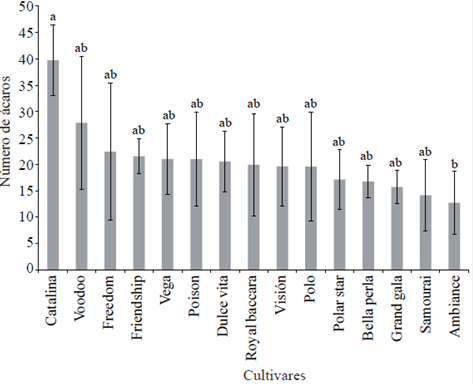

Mite infestation per plant was statistically significant (α≤ 0.05) and two groups of contrasting cultivars (Figure 1) were identified. In the first group cv. catalina was the most susceptible to the mite; the second group included ambiance as the toughest. This is contradictory because in the current rose cultivated a reduction should be expected in genetic variation due to advanced process of domestication and improvement linked to only 7 of more than 100 species used (Martin et al., 2001), but its many and complex hybridizations are likely to be the main factor of this variability.

Figure 1 Number of mites per plant recorded 15 rose cultivars from flower bud formation to the phenological stage of “large peas”. On the bars the standard deviation of the mean is indicated. Bars with the same letter are the same significantly (Tukey, α= 0.05).

In Mexico enterprises engaged in production of pink do research that are related to the development of new cultivars from the exploitation of genetic variation; no studies on self-defense of the plant either directly, through synthesis products, or indirectly attraction of natural enemies, against herbivores are known (Agrawal et al., 2002; Boege y Marquis, 2005). All cultivars are imported, which increases production costs.

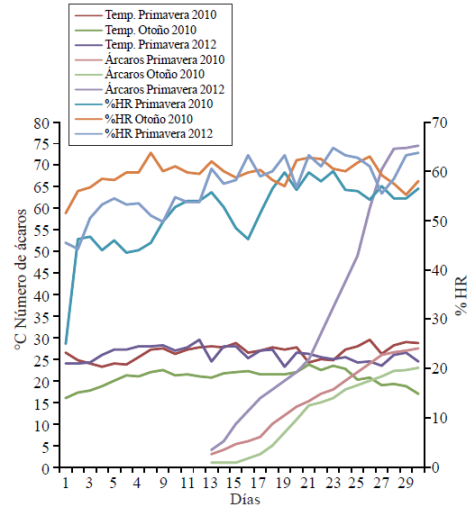

Environmental variables associated with the mite population development

Variations in temperature, relative humidity and their interaction affected the population growth of mites per plant per season evaluated (Figure 2). In spring 2012 there was a temperature of 26 °C and a relative humidity of 60%; both they favored the increase in the population of T. urticae. These results coincide with those of other studies where the intervals 25-28 °C and 60-70% represented the optimum development of this pest conditions (Kheradpir et al., 2007). In spring 2010 the average temperature was very similar to 2012, but the relative humidity was 56.5%. In autumn 2010 the temperature and relative humidity were 20.7 °C and 58% so the number of mites per plant was below those recorded in the other two production cycles (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Relationship between number of mites per plant, temperature and relative humidity in the variety catalina recorded in the three experiments.

The optimal development mite temperatures also promote the increase of females (Rasmy et al., 2011); perhaps the differences observed between spring 2012 with the other two production cycles attributed to an increase in them. Another environmental factor that can affect mite population growth is the fertilization of the plant (Chow et al., 2009; Flores et al., 2011).

The differential response in the mite population development, also could be affected by defense mechanisms of the plant as physical barriers or metabolic products. The total phenolic content measured in some cultivars (Figure 3), elected by their means and extreme values in incidence of mites (Figure 1) also showed natural variation; could be detected tend to be higher in cultivars with lower incidence of red spider.

Figure 3 Contents of total phenols in photosynthetically active leaves of flowering stems of certain rose in the phenological stages arrocillo, marble and cut point. On the bars the standard deviation of error is indicated.

Other authors have reported that phenolic compounds can be constitutively in plants or synthesized in response to infection pest (Gardner et al., 1999), where they accumulate more and more rapidly resistant mite species, with the presence of a pathogen (Khatun et al., 2009), in healthy leaves (Coruh and Ercisli, 2010), or even the agronomic management and environmental variables present; their presence also represent an evolutionary gain delay damage in adverse to the plant environmental conditions (Gardner et al., 1999).

Other biochemical factors of primary metabolism (anti-stress molecules) and secondary (terpenes, tannins and essential oils) constitutive and induced character and morphological structures (stomata, waxes, glands, sheet thickness, etc.) can also influence attracting or repelling mite (Graham et al., 2008; Mumm and Dicke, 2010; Flores et al., 2011), all within a complex relationship between parasite and host must individually explored (Hernandez et al., 2002; Vivanco et al., 2005). All these elements can be complementary criteria in integrated crop management and genetic improvement (Chow et al., 2009). Recent studies, in addition to environmental management, report the use of volatile compounds from plant leaves as Cleome gynandra L./ Gynandropsis gynandra (L.) Briq.), which in co-culture with Rosa x hybrida for cut flower production without affecting its performance and quality, it has substantially reduced the populations of T. urticae (Nyalala et al., 2013).

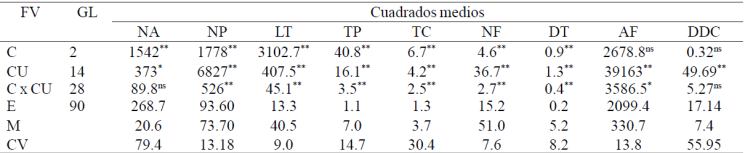

Variables associated with quality floral stem

Highly significant differences among cultivars (α= 0.01) were observed in all variables associated with quality floral stem, which directly reflect the existing phenotypic variability. The characteristics with greater range of variation among cultivars were number of petals, leaf area, stem length, productive stems, blind stems, number of leaflets and stem diameter (NP, AF, LT, TP, TC, NF, DT; Table 2). The environmental effects associated with the three production cycles also affected the development of cultivars to be observed highly significant differences in all variables except AF. The significant interaction C x CU observed in all variables except the chlorophyll content, suggest a differential response of cultivars to environmental factors prevailing in the three cycles of growth and development; in cv. beautiful pearl, the lowest temperatures observed in autumn 2010 in relation to the other two cycles, originated slow growth of the flower stem and had a greater number of short stems without flower (blind stems), probably also affected by the photoperiod. The cutoff point average in all cultivars also extended phenological cycle in 20 days.

Table 2 Mean squares and statistical significance of the F values of three experiments established for evaluating rose cultivars.

Variations in chlorophyll contents among cultivars were not significant; this fact could be considered the less variable varietal effect influencing the color tone of the leaves, but a greater dispersion in tissue damage was observed with mites, which highlights the decrease of photosynthetic activity in certain cultivars. Similar results were also observed in coffee leaves (coffea sp; Neves et al., 2006), also reports synthesis of metabolic products.

Mites vs physiological variables

Population growth mite (NA) in all cultivars rose was correlated negatively and significantly with some quality variables f lower stem as stem length, stem diameter and leaf area (LT, DT and AF; Table 3). The NA with the contents of chlorophyll in the leaves also showed a similar trend.

Golawska et al. (2010)), Calatayud et al. (2008), Neves et al. (2006) and Stone et al. (2001) observed a significant decrease in the values of physiological variables of the plant to increase the plague poblacionalmente, with direct effects on the commercial quality of the flower stalk (Tjosvold and Chaney, 2001). The interruption in the development of floral structure increases with population growth of T. urticae, but not significantly; probably the soil and climate factors and their interaction with the type of farming have a greater effect on these responses.

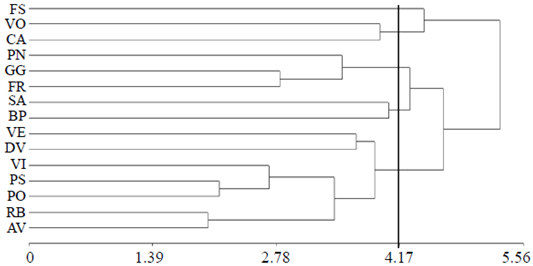

Cluster analysis

The data for the 15 cultivars rose and the evaluated variables were subjected to a multivariate analysis method unweighted arithmetic average (UPGMA Method). In this, considering an average distance of 4.17 ligation five groups (Table 4) were identified in group 1 it was only observed in cv. Friendship (FS), improved in France, bicolor flower in red and cream, and tolerance level red spider statistically equal to that shown by the best cultivars, catalina, voodoo and freedom (Figures 1 and 3). The second group contains cv. catalina and voodoo which were characterized by hosting the largest number of mites (NA, Figure 1). The cv. catalina was obtained by breeders in New Zealand and in terms of geographical distance represents the place of isolation from the places where the other cultivars studied, which was in European countries (Table 1) were developed. The cv. voodoo, developed in the Netherlands, is reported in California, United States of America as resistant to diseases (Anonymous 3, 1978). The third group contains cv. poison, freedom and grand gala originating in the Netherlands, Germany and France, respectively; in the last two, red flower, no information about their parents was found, so it is unknown whether both and poison, purple flower, are related.

Table 4 Mean variables evaluated 15 cultivars pink, grouped by cluster analysis.

G= grupos; Pr= promedio; NA= número de ácaros por planta; NP= número de pétalos; LT= longitud del tallo floral; TP= tallos productivos; TC= tallos ciegos; NF= número de foliolos; DT= diámetro de tallo floral; AF= área foliar; CSD= clorofila sin daño; CCD= clorofila con daño.

The fourth group was integrated with samourai and beautiful pearl, developed in France by different companies and contrasting progenitors and flower color. Both cultivars formed the group with the least damage tolerance caused by mites (Figure 1). The fifth group represents almost 50% of the cultivars evaluated; vega, sweet vita, vision, polar star, polo, and baccara royal ambiance are five tones contrasting flower color. The cv. and polar pole star, white flower, formed a subgroup but their parents are unknown, it is not possible to infer whether there is relationship between them. Based on the perception of farmers in the study area cultivar pole it is one of the most susceptible to pests and diseases and this polar star and were developed by the same company in Germany.

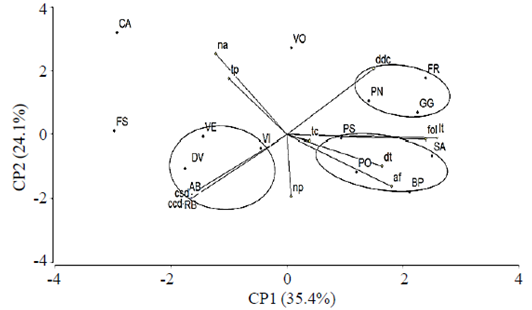

The 15 cultivars analyzed in the dendrogram of Figure 4 belong to the group of hybrid tea, considered the most representative in the category of modern roses, obtained by hybridizing rose’s tea groups and hybrid perpetual category of roses old. Roses present study, strictly classified as hybrid tea, represent a complex mixture reductively located in a narrow range of a wide genetic variation of more than 100 cultivars distributed in 13 groups of categories of modern roses and old (Martin et al., 2001). The principal components (CP) 1, 2 and 3 accounted for 72.5% of the original total variation; almost 50% was represented in the biplot using the CP 1 and 2 (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Dendogram to 15 rose cultivars obtained by the average linkage method (UPGMA method). FS= friendship; VO= voodoo; CA= catalina; PN= poison; GG= grand gala; FR= freedom; SA= samourai; BP= beautiful pearl; VE= vega; DV= sweet vita; VI= vision; PS= pole star; PO= pole; RB= royal baccara; AB= ambiance.

According to Sanchez (1995) and González et al. (2010) suggest these percentages reliability in the interpretation of the approximate correlations that can be detected among cultivars and variables evaluated in this study. In the three groups BIPLOT cultivars were observed for similar values identified by their proximity within a single quadrant. The first group included freedom cultivars, poison and grand gala (FR, PN and GG); the second group cultivars were the polar star, beautiful pearl samourai (PS, SA and BP); group three included vega, vision, sweet vita, ambiance and royal baccara (VE. VI, DV, AB and RB). The voodoo cultivars, chainring and friendship (VO, CA and FS) dissimilar in their scores on both CP 1 and 2, were not included in the above groups.

Principal component analysis

The CP1 is mainly explained by stem length (lt) and the number of leaflets (fol); CP2 was related essentially with number of mites (na) and productive stems (tp); CP3 and the highest scores were recorded in number of petals (np) and blind stems (TC). The CA, AM, SA, FR and GG cultivars had the highest scores in the CP1; CP2 was observed in CA and AB had the highest dispersion in the biplot graph and in the same situation CP3 detected with BO and PO (Figure 5).

In this biplot you can also note that CA, BO, FS and VE had the largest number of mites (NA) and productive stems. SA, GG, FR, BP, PN, PO and PS were the most outstanding in stem length (lt), number of leaflets (fo), leaf area (af), stem diameter (dt), unlike chlorophyll (ddc), number of petals (np) and blind stems (tc). RB, AB, DV and VI are mainly grouped by their content of chlorophyll damage (ccd) without damage (csd).

Conclusion

The population development of T. urtucae in rose in addition to being affected by environmental factors such as humidity and temperature, so is the differential response of cultivars in their natural defense complex mechanisms including metabolic products of the plant, which is reflected in flower stem quality measured in ten different parameters. Moreover, the variation in population growth mite among cultivars indicates that although the modern roses are the product of a narrow range of more than 100 species, they preserve genetic variability, possibly as a result of complex cross that gave rise to them and could be exploited in breeding programs. The geographical distance between the origins of some cultivars coincided with the most extreme differential response of cultivars to the development of mite.

Literatura citada

Agrawal, A. A.; Janssen, A.; Bruin, J.; Posthumus, M. A. and Sabelis, M. W. 2002. An ecological cost of plant defense: attractiveness of bitter cucumber plants to natural enemies of herbivores. Ecology Letters. 5(3):377-385. [ Links ]

Anónimo 1. 2012. S. a. Roses, Clematis and Peonies and everything gardening related. http://www.helpmefind.com/rose/ pl.php?n=81463. [ Links ]

Anónimo 2. 2012. S.a. Poison. http://www.dutch-creations.nl/sp/252/product/poison.html. [ Links ]

Anónimo 3. 1978. Roses hybridized by Christensen, J. E. http://home.earthlink.net/~jchristensen/list.html (consultado julio, 2013). [ Links ]

Boege, K. and Marquis, R. J. 2005. Facing herbivory as you grow up: the ontogeny of resistance in plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20(8):441-448. [ Links ]

Calatayud, A.; Roca, D.; Gorbe, E. and Martinez, P. F. 2008. Physiological effects of pruning in rose plants cv. Grand Gala. Sci. Hortic. 116:73-79. [ Links ]

Chow, A.; Chau, A. and Heinz, K. M. 2009. Reducing fertilization for cut roses: effect on crop productivity and twospotted spider mite abundance, distribution, and management. J. Econ. Entomol. 102(5):1896-1907. [ Links ]

Coruh, S. and Ercisli, S. 2010. Interactions between galling insects and plant total phenolic contents in Rosa canina L. genotypes. Sci. Res. Essays. 5(14):1935-1937. [ Links ]

Flores, C. R. J.; Mendoza, V. R.; Landeros, F. J.; Cerna, C. E.; Robles, B. A. e Isiordia, A. N. 2011. Caracteres morfológicos y bioquímicos de Rosa x hybrida contra Tetranychus urticae Koch en invernadero. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 3:473-482. [ Links ]

Flores, D. A.; Silva, A. G.; Tapia, V. M. y Casáis, B. P. 2007. Susceptibilidad de Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae) colectada en Primula obconica Hance y Convolvulus arvensis L. a acaricidas. Agric. Téc. 67(2):219-224. [ Links ]

Golawska, S.; Krzyzanowski, R. and Lukasik, I. 2010. Relationship between aphid infestation and chlorophyll content in fabaceae species. Acta Biologica Cracoviensia Series Botánica 52(2):76- 80. [ Links ]

Graham, M. A.; Silverstein, K. A. T. and VandenBosch, K. A. 2008. Defensin-like genes: genomic perspectives on a diverse superfamily in plants. Crop Sci. 48(81):3-11. [ Links ]

Hernández, S. E.; Soto, H. M.; Rodríguez, A. J. y Colinas, L. T. 2002. Contenido de fenoles y actividad enzimática asociados con el daño provocado por cenicilla en hojas de durazno. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 25(2):153-160. [ Links ]

Khatun, S.; Bandyopadhyay, P. K. and Chatterjee, N. C. 2009. Phenols with their oxidizing enzymes in defense against black spot of rose (Rosa centifolia). Asian J. Exp. Sci 23(1):249-252. [ Links ]

Kheradpir, N.; Khalghani, J.; Ostovan, H. and Rezapanah, M.R. 2007. The comparison of demographic traits in Tetranychus urticae koch (acari: Tetranychidae) on five different greenhouse cucumber hybrids (Cucumis sativus). Acta Hortic. 747:425-430. [ Links ]

Martin, M.; Piola, F.; Chessel, D.; Jay, M. and Heizmann, P. 2001. The domestication process of the Modern Rose: genetic structure and allelic composition of the rose complex. Theoretical Appl. Gen. 102(2-3):398-404. [ Links ]

Mumm, R. and Dicke, M. 2010. Variation in natural plant products and the attraction of bodyguards involved in indirect plant defense. Can. J. Zool. 88(7):628-667. [ Links ]

Neves, A. D.; Oliveira, R. F. and Parra, J. R. P. 2006. A new concept for insect damage evaluation based on plant physiological variables. An. Acad. Bras. Cien. 78(4):821-835. [ Links ]

Nyalala, S. O.; Petersen, M. A. and Grout, B. W. W. 2013. Volatile compounds from leaves of the African spider plant (Gynandropsis gynandra) with bioactivity against spider mite (Tetranychus urticae). Ann. Appl. Biol. 162(3):290-298. [ Links ]

Rasmy, A. H.; Osman, M. A. and Abou-Elella, G. M. 2011. Temperature influence on biology, thermal requirement and life table of the predatory mites Agistemus exsertus Gonzalez and Phytoseius plumifer (Can. & Fanz.) reared on Tetranychus urticae Koch. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Protec. 44(1): 85-96. [ Links ]

SIAP. 2010. Estadísticas Agropecuarias. Disponible en http://www.siap.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Stone, C.; Chisholm, L. and Coops, N. 2001. Spectral reflectance characteristics of eucalypt foliage damaged by insects. Aust. J. Bot. 49(6):687-698. [ Links ]

Tjosvold, S. A. and Chaney, W. E. 2001. Evaluation of reduced risk and other biorational miticides on the control of spider mite (Tetranychus urticae). Acta Hortic. 547:93-96. [ Links ]

Vivanco, J. M.; Cosio, E.; Loyola-Vargas, V. M. y Flores, H. 2005. Mecanismos químicos de defensa en las plantas. Investigación y Ciencia. 341(2):68-75. [ Links ]

Received: February 2016; Accepted: June 2016

texto en

texto en