Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 n.3 Texcoco Apr./May. 2016

Articles

Efficiency of substrates in soil and hydroponic system for greenhouse tomato production

1Universidad Popular Autónoma del estado de Puebla-Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas. 11 poniente 2316, colonia Barrio de Santiago. C. P. Tel: 72410 222, Ext. 797. Puebla, Puebla. (luisdaniel.ortega@upaep.mx; beatriz.perez@upaep.mx).

2Instituto de Investigación en Ambiente y Salud-Universidad de Occidente. Boulevard Macario Gaxiola y Carretera Internacional. Los Mochis, Sinaloa. (maria.martinezv@udo.mx).

3Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Puebla. Carretera Federal México- Puebla, Santiago Momoxpan, km 125.5, municipio de San Pedro Cholula, Puebla. (Blvd. Forjadores). C. P. 72760. Tel: 01 222 2 85 00 13. (engelber@colpos.mx).

The substrates used in tomato production systems in Mexico under greenhouse conditions are so heterogeneous yields vary. In this study the efficiency of different substrates were evaluated: tezontle, coconut fiber and sawdust-compost mixture in the hydroponic system, as well as soil and soil with plastic mulch with fertigation in tomato production during the season 2013. Results showed that performance with a seeding density of 6 plants m-2 showed significant differences between the substrates, the yield was higher in the volcanic rock with an average of 25.2 kg m-2. Water consumption and nutrient solution was superior in treatments coir (2 708 L m-2) and tezontle (2158 L m-2), the best economic benefit (1.8 pesos) showed him the floor with plastic mulch, yield 23.3 kg m-2 and a coefficient of productivity 63.6 L water per kg m-2 tomato. So that the latter may represent an alternative in saving water and fertilizer.

Keywords: Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.; protected horticulture; nutrient solution

Los sustratos utilizados en los sistemas de producción de tomate en México bajo condiciones de invernadero son heterogéneos por lo que los rendimientos varían. En este estudio se evaluó la eficiencia de diferentes sustratos: tezontle, fibra de coco y la mezcla aserrín-composta en el sistema hidropónico, así como el suelo y suelo con acolchado plástico con fertirrigación en la producción de tomate durante el ciclo agrícola 2013. Los resultados mostraron que el rendimiento con una densidad de siembra de 6 plantas m-2 presentó diferencias significativas entre los sustratos, el rendimiento fue mayor en el tezontle con promedio de 25.2 kg m-2. El consumo de agua y solución nutritiva fue superior en los tratamientos de f ibra de coco (2708 L m-2) y tezontle (2158 L m-2), el mejor benef icio económico (1.8 pesos mexicanos) lo mostró el suelo con acolchado plástico, con un rendimiento de 23.3kg m-2 y un coeficiente de productividad de 63. L de agua por kg m-2 de tomate. Por lo que este último puede representar una alternativa en el ahorro de agua y de fertilizante.

Palabras clave: Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.; horticultura protegida; solución nutritiva

Introduction

In Mexico the production area with vegetables in conditions protected agriculture has increased in recent years (SIAP, 2010), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) Is the most widely cultivated vegetable, is currently experiencing a strong development in various regions and climate conditions, soil, water quality and agronomic management (Nieves et al., 2011). To produce the substrates used are heterogeneous, based mainly on climatic, agronomic and fertilization variables that can help increase their efficiency and profitability (Rucoba et al., 2006; Ortega et al., 2014). These variables interact with environmental and physiological factors, of which the producer has a degree of control over them, then applies its own management schemes according to its criteria (Bojaca et al., 2009).

An estimated 80% of horticultural production under plastic covers takes place in soil (Castellanos, 2004), however, it is handled as an inert substrate, it is not considered wealth and productive potential so it is common and continues the application of inorganic fertilizers, organic fertilizers and pesticides, based on the recommendations developed for other environmental conditions and production systems. It also generates an increase in production costs and environmental pollution (Alconada et al., 2000; Giuffre et al., 2004). This has also been reported elsewhere in the world (Moorman, 1998; Karami y Ebrahimi, 2000; Baixauli y Aguilar, 2002).

The choice of cultivating soil is based on benefits such as cushioning temporary interruptions of water and nutrient availability and increase the efficiency of these (Villarreal et al., 2002; Castellanos, 2004). However, it is widely recognized that agricultural soils are degradation process such as salinization, alkalinization, decreased permeability, nutrient imbalances and disease development (Alconada et al., 2011).

Several studies evaluating tomato yields in greenhouse using soil, show differences, mainly due to the various supplements that are used in the system as plastic toppers, nutrient solutions, addition of organic fertilizers and soil with different physical and chemical properties (Kirda et al., 2004; Ojodeagua et al., 2008; Alconada et al., 2011; Grijalva et al., 2011; Bouzo and Astegiano, 2012).

Likewise, the open hydroponics system is used by inert substrates such as volcanic rock (volcanic rock), sawdust, compost and coir (Gomez, 2003; Moreno and Valdes, 2005; Marquez et al., 2006; Rodriguez et al. , 2008; Vargas et al., 2008; Ortega et al., 2010; San Martin et al., 2012). The observed that one of the problems is the yield, which varies mainly by the physical and chemical each of the substrates used features; the interest in using different substrates and soil is based on lower costs, increased yield, fruit quality and optimal use of water and fertilizer (Inden and Torres, 2004).

To increase the yield of greenhouse tomato, contributed changes in production systems, technology, research and ways to investigate in the world, so there is a great need for local research, especially in countries like Mexico, where this type of technology is relatively new for most farmers (Baeza et al., 2006; Castañeda, 2007; Rico et al., 2007; Vazquez et al., 2007; Acuña ,2009; Ramos et al., 2010;López y Hernandez, 2010; Briceño et al., 2011).

The aim of this study was to compare the efficiency of different substrates in relation to the performance, utilization of water and nutrient solution in hydroponics and soil system for greenhouse tomato production.

Materials and methods

The research was conducted in the municipality of Chignahuapan in the morphological region of the Sierra Norte of Puebla in 2013. The climate corresponds to C(w1) temperate subhumid, annual average temperature between 12 and 18°C. The total annual rainfall in the area varies from 600 to 1 000 mm (SMRN, 2007). A greenhouse of 1 000 m2 for temperate climate with overhead window polyethylene considered. The maximum and minimum average temperatures in the greenhouse were 3 and 31°C. Cultivated tomato variety Suun 7 705 the company Nunhems indeterminate growth. The volcanic rock substrates (red volcanic rock), coir and the mixture of sawdust-composted sheep in the ratio 1:1 were evaluated in the open hydroponics system. As well as soil and soil with plastic mulch. Table 1 shows the physical characterization of each treatment is presented. The experimental design was completely randomized blocks, 5 treatments were evaluated, with 8 repetitions each experimental unit consisted of 15 plants, with a spacing of 30 cm between them; and a topological arrangement staggered by adjusting the distribution was used, the response variable was the performance.

Volume, bulk density and particle density, determined by the method proposed by method De Boodt et al. (1974). The total pore space (%) (1- Da/Dr) x 100 retained water. Determined by the method proposed by Martinez (1992). CE electric conductivity determined by properties measured in saturated extract, described by Warncke (1988) and pH Measured using a conductivity/potentiometer HI 98312 DiST® Hanna Instrumenst.

For treatments with substrates, the volume per plant was 10 L and deposited in polyethylene bags gauge 70 for padding ground, black / silver polyethylene was used supplemented with antioxidants and protectors of ultra violet rays, black / silver caliber 90. The planting density was 6 m-2. For the supply of nutrient solution was available irrigation facility through time, which was to establish a timetable with a defined frequency for 24 h. which was adjusted according to the percentage of retained water. He also was collected and quantified the solution drained substrates hydroponic systems.

Two nutritious solutions were used for treatments (Table 2) based on the results of analysis of soil and water and were designed from calcium nitrate, potassium nitrate, magnesium sulfate, potassium sulfate and phosphoric acid more microelements.

The efficiency of substrates and soil was determined by ratios used amount of water, fertilizers and tomato weight produced per square meter, total yield, and trade, and the fruits were classified according to their diameter boys (4-6 cm), medium (6-8 cm), large (≥ 8 cm). For purposes of this work were separated from the total trade performance, those fruits with less than 4 cm and those who had some physiopathy diameter. The variables were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and mean comparison tests Tukey (α= 0.01) and correlations, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Also sought economic information on the investment made for each substrate as well as production costs and income from the local sale of tomato was also collected subsequently determined profitability through cost-benefit indicator.

Results and discussion

The tomato yield significant differences (α= 0.01) between treatments, highlighting the hydroponic system using the tezontle substrate with an average of 25.2 kg m-2 (Table 3) stating that the physical characteristics of the substrate impacted production capacity. These results are superior to those obtained by Ortega et al. (2010) with 19.6 kg m-2 when using the same substrate but lower than Ojodeagua et al. (2008) with 34.1 kg m-2 and San Martin et al. (2012) using mixture of volcanic rock with coir dust under greenhouse conditions. The soil with plastic mulch showed a yield of 23.3 kg m-2, the higher the floor unpadded 19.4 kg m-2, even if their physical characteristics are equivalent, these results were similar to those reported by Villarreal (2002) and Macías et al. (2010).

Table 3 Efficiency of water and fertilizer on tomato yield.

†Letras distintas en la misma columna indican diferencias significativas según la prueba de Tukey (α= 0.01). C/B= costo beneficio. SN= solución nutritiva.

Regarding the sawdust-compost mixture was statistically lower in yield with respect to volcanic rock and soil with plastic mulch, results that do not match Bures (1997); Nelson (1991); Strojny and Nowak (2001), who report that a material alone is difficult to comply with the best physical and chemical development of plants conditions. So it is necessary to make mixtures of materials with different physical and chemical properties. However, consistent with the results presented for treatment of coconut fiber, which showed the highest consumption of water and nutrient solution and lower yield (16.8 kg m-2). This consumption could result in the overuse of these fertilizers as mentioned Villarreal et al. (2009) results, in addition to an increase in production costs, nutritional imbalances in crops and environmental pollution problems.

Moreover, the treatment tezontle obtained 55% higher fruit to 8 cm, followed plastic mulch soil 52%, (Figure 1), similar to Ojodeagua et al. (2008), when evaluating tezontle and soil, both treatments showed the least amount of small fruits, 4-6 cm (8%).

Similarly, the cost-benefit results show that most of the treatments evaluated are profitable except coir (Table 3). However, despite the tezontle treatment presented the best yields, soil with plastic mulch had the best benefit, because for every peso invested 0.8 pesos was obtained. Higher costs were labor and fertilizer results that are similar to those of Rucoba et al. (2006).

Efficiency of water and nutrient solution

The increased water consumption and nutrient solution per kilogram of tomatoes produced was presented in the coir (2 708 L - 16.8 kg m-2) and tezontle (2 158 L - 25.2 kg m-2), these results may be influenced by low water retention, showing a highly significant correlation between yield and percentage of water retained (Table 4). Results agree with those obtained by Vargas et al. (2008). However, they differ with those obtained by Abad et al. (2004); Tahi et al. (2007), indicating that the production of greenhouse vegetables is one of the alternatives that are carried out to achieve a sustainable use of water, being important to note that this study consisted of free drainage system; It is an open hydroponic system, so that the water and the nutrient solution is not reused, which shows a low efficiency.

Table 4 Correlations between performance, water, nutrient solution and physical characteristics of the substrates.

*La correlación es significante al nivel α= 0.01**. N= nitrógeno; Ca= calcio; K= potasio; P= fósforo; Mg= magnesio; V= volumen; EPT= espacio poroso total.

Treatments for soil and soil with plastic mulch, no significant differences were found in water consumption and nutrient solution, but not in performance (Table 2). Brouse et al. (2006)) mention that the plastic mulch soil has a negative impact, because it leads to biological degradation of soil, creating an adverse impact on the environment (Peña et al., 2001), air pollution (Ramanathan et al., 1985), soil (Castellanos and Peña, 1990) and groundwater, and surface water eutrophication (Gilliam et al., 1985). In addition, consumption of water and fertilizers in both treatments (soil and soil with plastic mulch), was significantly lower, at the tezontle, but are not considered sustainable production systems. For that reason producers from different countries have adapted organic soilless cultivation practices (Inden and Torres, 2004; Grigatti et al., 2007; Jordan et al., 2010). Unlike Mexico where the soil is widely used in different cultures (Inzunza et al., 2007; Munguía et al., 2011; Gutiérrez et al., 2010; Cih et al., 2011).

The correlation matrix performance (Ren) (Table 4) with water applied (AP), consumption of nutrient solution (SN), substrate volume (V), total pore space (EPT) and retained water (AR); was highly significant (α= 0.01) and inversely proportional to Ren with V, EPT, significant and inversely proportional with AP and AS; and significant and directly proportional with AR, these effects are similar to those obtained by other authors (Adams, 1986; FAO, 1990; Chung et al., 1992; Chi y Han,1994; Cadahia, 2005), who mentioned that there significant effect on performance by using different concentrations within the range 10 to 320 mg L-1 of nitrogen, 5 to 200 mg L-1 of phosphorus and 20 to 300 mg L-1 potassium. It should be noted that these results have been developed for closed hydroponic systems involving recirculation of the nutrient solution for later use.

There was a highly significant correlation in water consumption and efficiency of fertilizers, i.e. the higher the cost of nutrient solution fertilizer use increases and being systems where it is not recirculated, as mentioned (Volke et al., 1993; Crovetto, 1996) produce physical, chemical and biological degradation, due to the decrease in organic matter content, the residual accumulation of soluble salts and reduce the microbial population. Furthermore, the use of nitrogen fertilizer in excess of crop requirements high emissions of nitrogen into the atmosphere dioxide quantities, which contributes to the greenhouse effect and the destruction of the ozone layer (Baggs et al., 2003).

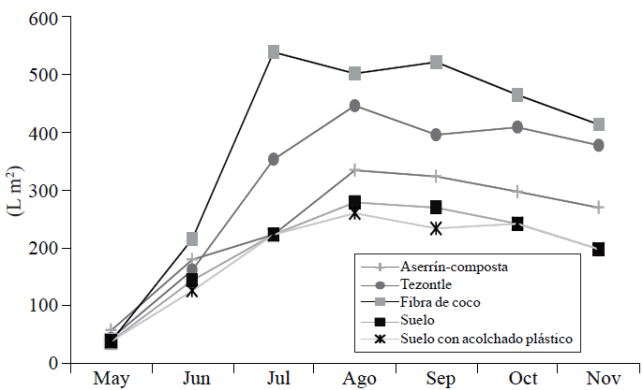

The amount of water the tomato plants are applied at different stages of growth and development in treatments increased as time passed, the most was during july, august and september months (Figure 2), together with the increased solar radiation (Radin et al., 2004). The soil with plastic mulch, showed the highest rate of use of water (63.6 L kg), 50% and 48% lower than the cost of fiber substrates coconut and tezontle respectively (Table 2), the applied amount is higher than the recommended by Albiac, (2004). However, the results obtained is within the range of those by other authors (Ojodeagua et al., 2008; Alconada et al., 2011; Yescas et al., 2011).

Conclusions

In regions temperate sub-humid with temperatures ranging between 12 and 18 °C, it is important tomato production in greenhouses, even if environmental conditions inside it can reach more extreme temperatures, affecting yields, water efficiency and fertilizer. However, the types of substrates used are considered in research whose results indicate what is best for the benefit of producers.

Efficiency in water and fertilizer is achieved by soil culture plastic mulch, it is about 50% compared with the substrates coir and tezontle with hydroponics.

The differences obtained in performance between treatments may be effect of physical and chemical properties of the substrates tested, and by the use of plastic mulch.

The performance showed significant differences, highlighting the tezontle, however, treatment with plastic mulch floor, showed the best economic benefit.

Literatura citada

Abad, B.; Noguera, M. y Carrión, B. 2004. Los sustratos en los cultivos sin suelo. In: tratado de cultivo sin suelo. Urrestarazu, G. M. (Ed.). Mundi-Prensa. Madrid, España. 113-158 pp. [ Links ]

Acuña, C. J. 2009. Control climático en invernaderos. Ingeniería e Investigación. 3:149-150. [ Links ]

Adams, P. 1986. Mineral nutrition. Chapman and Hall. London, UK. 281-334 pp. [ Links ]

Albiac, J. 2004. El modelo para el análisis del sector agrario: necesidades hídricas de los cultivos. Instituto Juan de Herrera. Madrid, España. http://habitat.aq.upm.es/boletin/n27/ajalb4.html (consultado octubre, 2013). [ Links ]

Alconada, M.; Giuffre, L.; Huergo, L. y Pascale, C. 2000. Hiperfertilización con fósforo de suelos Vertisoles y Molisoles en cultivo de tomate protegido. Avances en Ingeniería Agrícola. Editorial Facultad de Agronomía. 343-347 pp. [ Links ]

Alconada, M.; Cuellas, M.; Poncetta, P.; Barragán, S.; Inda, E. y Mitidieri, A. 2011. Nutrición nitrogenada. Efectos en el suelo y en la producción. Horticultura Argentina. 30:(72)5-13. [ Links ]

Baeza, E.; Pérez, P.; López, J. and Montero, J. 2006. Study of the natural ventilation performance of a parral type greenhouse with different numbers of spans and roof vent configurations. Acta Hortic. 719:333-340. [ Links ]

Baggs, E.; Stevenson, M.; Pihlatie, M.; Regar, A.; Cook, H. and Cadisch, G. 2003. Nitrous oxide emissions following application of residues and fertilizer under zero and conventional tillage. Plant and Soil. 254(2):361-370. [ Links ]

Baixauli, S. y Aguilar, O. 2002. Cultivo sin suelo de hortalizas. Generalitat Valenciana. Valencia, España. Serie de Divulgación Técnica Núm. 53. 110 p. [ Links ]

Bojacá, R. B.; Yurani, N. y Monsalve, O. 2009. Análisis de la productividad del tomate en invernadero bajo diferentes manejos mediante modelos mixtos. Rev. Colom. Cienc. Hortíc. 3:(2)188-198. [ Links ]

Bouzo, C. A. y Astegiano, E. 2012. Efectos de diferentes agroecosistemas en la dinámica de nitrógeno, fósforo y potasio en un cultivo de tomate. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 3(5):907-924. [ Links ]

Briceño, M. L.; Ávila, M. y Jaimez, R. 2011. Modelo de simulación del microclima de un invernadero. Agrociencia. 45(5):801-813. [ Links ]

Brouse, S.; Kirkegaard, J.; Pratley, Y. and Howe, G. 2006. Growth suppression of canola through wheat stubble. I. Separating physical and biochemical causes in the field. Plant and Soil. 281:203-218. [ Links ]

Burés, S. 1997. Sustratos. Ediciones Agrotécnicas S. L. Madrid, España. 352 p. [ Links ]

Cadahía, L. C. 2005. Fertirrigación, cultivos hortícolas, frutales y ornamentales. Mundi-Prensa. Madrid, España. 399-354 pp. [ Links ]

Castañeda, M. R.; Ramos, V.; Peniche, R. y Herrera, G. 2007. Análisis y simulación del modelo físico de un invernadero bajo condiciones climáticas de la región central de México. Agrociencia. 41(3):317-335. [ Links ]

Castellanos, R. J. y Peña, J. 1990. Los nitratos provenientes de la agricultura: una fuente de contaminación de los acuíferos. Terra Latinoam. 8:113-126. [ Links ]

Castellanos, R. J. 2004. Manual de producción hortícola en invernadero. INTAGRI. México, D. F. 103-123 pp. [ Links ]

Chi, S. and Han, G. 1994. Effect of nitrogen concentration in the nutrient solution during the first 20 days after planting on the growth and fruit yield of tomato plants. J. Korean Soc. Hort. Sci. 35(5):415-420. [ Links ]

Chung, S.; Seo, B. and Lee, B. 1992. Effects of nitrogen and potassium levels and their interaction on the growth and development of hydroponically grown tomato. J. Korean Soc. Hort. Sci. 33(3):244-251. [ Links ]

Cih-Dzul, I.; Jaramillo, J.; Tornero, M. y Schwentesius, R. 2011. Caracterización de los sistemas de producción de tomate (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) en el estado de Jalisco, México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosys. 14:501-512. [ Links ]

Crovetto, C. 1996. Stubble over the soil. The vital role of plant residue in soil management to improve soil quality. Special publication American Society of Agronomy. Madison, WI, USA. 245 p. [ Links ]

De-Boodt, M.; Verdonck, O. and Cappaert, R. 1974. Methods for measuring the water release curve of organic substrates. Acta Horticulturae. 37:2054-2062. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 1990. Soilless culture for horticultural crop production. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Roma, Italia. 102 p. [ Links ]

Gilliam, J.; Logan, T. and Broadbent, F. 1985. Fertilizer use in relation to the environment. In: fertilizer technology and use. Third edition. Soil Science Society of America. Madison, WI, USA. 561-588 pp. [ Links ]

Giuffré, L.; Alconada, M.; Pascalem, C. and Ratto, S. 2004. Environmental impact of phosphorus over fertilization in tomato greenhouse production. J. Appl. Hortic. 6(1):58-61. [ Links ]

Gómez, H. T. y Sánchez, C. 2003. Soluciones nutritivas diluidas para la producción de jitomate a un racimo. Terra Latinoam. 21(1):57- 63. [ Links ]

Grigatti, M.; Giorgioni, M.; Cavani, L. and Ciavatta, V. 2007. Vector Analysis in the study of the nutritional status of Philodendron cultivated in compost-based media. Scientia Hortic. 112 (4):448-455. [ Links ]

Grijalva, C. R.; Macías, D. y Robles, C. 2011. Comportamiento de híbridos de tomate bola en invernadero bajo condiciones desérticas del noroeste de Sonora. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosys. 14(2):675-682. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, V. C.; Serwatowski, R.; Cabrera, S.; Saldaña, R. y Juárez, G. 2010. Estudio de corte de películas plásticas sobre suelos acolchados. Ciencias Técnicas Agropecuarias. 19(4):30-36. [ Links ]

Inden, H. y Torres, A. 2004. Comparison of four substrates on the growth and quality of tomatoes. Acta Hort. 6(44):205-210. [ Links ]

Inzunza, I. M.; Mendoza, M.; Catalán, V.; Castorena, M.; Sánchez, C. y Román, L. 2007. Productividad del chile jalapeño en condiciones de riego por goteo y acolchado plástico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 30(4):429-436. [ Links ]

Jordán, A.; Zavala, A. y Gil, A. 2010. Effects of mulching on soil physical properties and runoff under semi-arid conditions in southern Spain. Rev. Catena. 81(1):77-85. [ Links ]

Karami, E. and Ebrahimi, H. 2000. Overfertilization with Phosphorus in Iran: a sustainability problem. J. Ext. Systems. 16:100-120. [ Links ]

Kirda, C.; Cetin, M.; Dasgan, Y.; Topcu, S.; Kaman, H.; Ekici, B.; Derici, M. R. and Ozguven A. I. 2004. Yield response of greenhouse grown tomato to partial root drying and conventional deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 69(3):191-201. [ Links ]

López, C. I. y Hernández, L. 2010. Modelos neuro-difusos para temperatura y humedad del aire en invernaderos tipo cenital y capilla en el centro de México. Agrociencia. 44:791-805. [ Links ]

Macías, D. R.; Grijalva, R. y Robles, F. 2010. Efecto de tres volúmenes de agua en la productividad y calidad de tomate bola (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) bajo condiciones de invernadero. Biotecnia. 7(2):11-19. [ Links ]

Márquez, H. C.; Cano, R.; Chew, M.; Moreno, R. y Rodríguez, D. 2006. Sustratos en la producción orgánica de tomate cherry bajo invernadero. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 12(2):183-189. [ Links ]

Martínez, F. 1992. Propuesta de metodología para la determinación de las propiedades físicas de los sustratos. Actas Hortic. 11:55-66. [ Links ]

Moorman, G. 1998. Overfertilization. The Pennsylvania State University. www.cas.psu.edu/docs.casdept/plant/ext/overfert (consultado noviembre, 2013). [ Links ]

Moreno, R. A. y Valdés, P. 2005. Desarrollo de tomate en sustratos de vermicompost/arena bajo condiciones de invernadero. Agric. Téc. 65(1):26-34. [ Links ]

Munguía, L. J.; Zermeño, G.; Quezada, M.; Ibarra, J. y Arellano, G. 2011. Balance de energía en el cultivo de chile morrón bajo acolchado plástico. Terra Latinoam. 29(4):431-440. [ Links ]

Nelson, P. V. 1991. Greenhouse operation and management. Prentice- Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA. 611 p. [ Links ]

Nieves, G. V.; Van der Valk, O. and Elings, A. 2011. Mexican protected horticulture: Production and market of Mexican protected horticulture described and analyzed wageningen ur greenhouse horticulture. Landbouw Economisch Institute. The Hague. Minister of Economic Affairs. Rapport GTB-1126. 104 p. [ Links ]

Ojodeagua, A. J.; Castellanos, J.; Muñoz, R.; Alcántar, R.; Tijerina, G.; Vargas, Ch. y Enríquez, R. 2008. Eficiencia de suelo y tezontle en sistemas de producción de tomate en invernadero. Fitotec. Mex. 31:367-374. [ Links ]

Ortega, M. L.; Sánchez, O.; Ocampo, M.; Sandoval, C.; Salcido, R. y Manzo, R. 2010. Efecto de diferentes sustratos en crecimiento y rendimiento de tomate (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) bajo condiciones de invernadero. Ra Ximhai. 6(3):339-346. [ Links ]

Ortega, M. L.; Ocampo, M.; Sandoval, C.; Martínez, V.; Huerta de la Peña, A. y Jaramillo, J. 2014. Caracterización y funcionalidad de invernaderos en Chignahuapan, Puebla, México. Biociencias. 2(4):261-270. [ Links ]

Peña, C. J.; Grajeda, C. y Vera, N. 2001. Manejo de los fertilizantes nitrogenados en México: uso de las técnicas isotópicas (15N). Terra Latinoam. 20:51-56. [ Links ]

Radin, B.; Reisser, J. y Matzenauer, H. 2004. Crescimiento de cultivares de alface conduzidas em estufa e a campo. Hort. Bras. 22:178-181. [ Links ]

Ramanathan, V.; Cicerone, H. e Kiehl, J. 1985. Trace gas trends and their potential role in climate change. J. Geophy. Res. Atmospheres. 90(D3): 5547-5566. [ Links ]

Ramos, F. J.; López, M.; Enea, G. y Duplaix, J. 2010. Una estructura neurodifusa para modelar la evapotranspiración instantánea en invernaderos. Ingeniería, Investigación y Tecnología. 11(2):127-139. [ Links ]

Rico, G.; Castañeda, M.; García, E.; Lara, H. y Herrera, R. 2007. Accuracy comparison of a mechanistic method and computational fluid dynamics (cfd) for greenhouse inner temperature predictions. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 13(2):207-212. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, D. N.; Cano, P.; Figueroa, V.; Palomo, G.; Favela, C.; Álvarez, P.; Márquez, H. y Moreno, R. 2008. Producción de tomate en invernadero con humus de lombriz como sustrato. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 31(3):265-272. [ Links ]

Rucoba, G. N.; Anchondo, N.; Lujan, A. y Olivas, G. 2006. Análisis de rentabilidad de un sistema de producción de tomate bajo invernadero en la región centro-sur de Chihuahua. Rev. Mex. Agron. 10(19):2-5. [ Links ]

San Martín, H. C.; Ordaz, C.; Sánchez, G.; Beryl, C. y Borges, G. 2012. Calidad de tomate (Solanum llcopersicum L.) producido en hidroponía con diferentes granulometrías de tezontle. Agrociencia. 46:243-254. [ Links ]

SMRN. 2007. Diagnóstico socioeconómico y de manejo forestal unidad de manejo forestal Zacatlán. Asociación Regional de Silvicultores Chignahuapan-Zacatlán A. C. Puebla, México. 281 p. [ Links ]

SAGARPA-SIAP. 2010. http://www.siap. gob.mx/sistema_productos. [ Links ]

Strojny, Z. and Nowak, J. 2001. Effect of different growing media on the growth of some bedding plants. Acta Hortic. 644:157-162. [ Links ]

Tahi, H.; Wakrim, R.; Agachich, B. and Centritto, M. 2007. Water relations, photosynthesis, growth and water use efficiency in tomato plants subjected to partial rootzone drying and regulated deficit irrigation. Plant Biosys. 141(2):265-274. [ Links ]

Vargas, T. P.; Castellanos, R.; Muñoz, R.; Sánchez, G.; Tijerina, C.; López, R.; Martínez, S. y Ojodeagua, A. 2008. Efecto del tamaño de partícula sobre algunas propiedades físicas del tezontle de Guanajuato. México. Agric. Téc. Méx. 34(3):323-331. [ Links ]

Vázquez, R. J.; Sánchez, C. y Moreno, E. 2007. Producción de jitomate en doseles escaleriformes bajo invernadero. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 13(1):55-62. [ Links ]

Villarreal, R.; Parra, T.; Sánchez, P.; Hernández, V.; Osuna, E.; Corrales, M. y Armenta, A. 2009. Fertirrigación con diferentes formas de nitrógeno en el cultivo de tomate en un suelo arcilloso. Interciencia. 34 (2): 135-139. [ Links ]

Villarreal, R. M.; García, E. y Osuna, A. 2002. Efecto de dosis y fuente de nitrógeno en rendimiento y calidad de poscosecha de tomate en fertirriego. Terra Latinoam. 20:311-320. [ Links ]

Volke, H.; Reyes, F. y Merino, B. 1993. La materia orgánica del suelo como función de factores físicos y el uso y manejo del suelo. Terra Latinoam.11:85-92. [ Links ]

Warncke, D. 1988. Recommended test procedure for greenhouse growth media. In: Recommended chemical soil test procedures for the North Central Region. Bulletin 499. North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station. Fargo. 34-37 pp. [ Links ]

Yescas, C. P.; Segura, C.; Orozco, V.; Enríquez, S.; Sánchez, S.; Frías, R.; Montemayor, T. y Preciado, R. 2011. Uso de diferentes sustratos y frecuencias de riego para disminuir lixiviados en la producción de tomate. Terra Latinoam. 29(4):441-448. [ Links ]

Received: January 2016; Accepted: April 2016

text in

text in