Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 no.1 Texcoco ene./feb. 2016

Articles

Mexico’s dependence on maize imports in the age of NAFTA

1Canal de la Mancha #296 interior 17- c Fraccionamiento Magnolias C.P. 32424, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

2Departamento de Economía de El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Km. 18.5 Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, San Antonio del Mar, C.P. 22560, Tijuana, Baja California, Tel. (664) 6316300 ext. 3423. (salvador@colef.mx).

3Economía del Instituto de Socioeconómica y Estadística del Colegio de Postgraduados en Ciencias Agrícolas. Km. 36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco Montecillo, Texcoco, C.P. 56230, Estado de México, Tel. (595) 9520200. (matusgar@colpos.mx).

The internal maize production has not been sufficient to supply domestic demand. On the other hand, imports of the grain have increased due to trade openness and especially since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which is the result of changes on agricultural policies. This paper analyses the context of national maize production, the changes made since NAFTA was enacted and the development of Mexico's dependence on maize imports. The methodology used is the following. First an exploratory analysis was carried out on the supply and demand of maize in Mexico from 1980-2011. Subsequently, in order to identify the main variables that determine the supply and demand, a system of simultaneous equations was laid out, which was estimated through the two-stage least squares method. The results show that Mexico has a growing dependence on maize imports and also that the internal market is mainly influenced by the rural expected average price. It is recommended to analyze and reestablish the role of the State in promoting more convincing and effective fostering policies in the agricultural sector.

Keywords: food security; maize demand; model of simultaneous equations; maize supply

La producción interna de maíz ha sido insuficiente para abastecer la demanda doméstica. Por otra parte, las importaciones del grano han ido en aumento a partir de la apertura comercial y en especial desde el Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (TLCAN), lo cual es resultado del cambio de políticas agrícolas. Este documento analiza el contexto de la producción nacional de maíz y los cambios a partir de la entrada en vigor del TLCAN y el desarrollo de la dependencia a las importaciones de maíz por parte de México. La metodología empleada es la siguiente, primero se realiza un análisis exploratorio de la oferta y la demanda de maíz en México en el periodo de 1980 a 2011, después con la finalidad de identificar las principales variables que determinan la oferta y demanda se plantea un sistema de ecuaciones simultáneas, el cual se estima a través del método de mínimos cuadrados en dos etapas. Los resultados indican que México presenta una creciente dependencia a las importaciones de maíz y también que el mercado interno está influenciado principalmente por el precio esperado medio rural. Se recomienda analizar y replantear el papel del Estado promoviendo en el sector políticas de fomento más contundentes y efectivas.

Palabras clave: demanda de maíz; modelo de ecuaciones simultáneas; oferta de maíz; seguridad alimentaria

Introduction

Regarding the behavior of consumption and production per capita in Mexico from 1980-2010, two points in time have been observed where the production per capita has almost fully supplied the consumption: in 1982 when the consumption surpassed by 3.5 kg, and in 1993 when the consumption surpassed by 1.5 kg. Likewise, it can be observed that the behavior of consumption and production is similar in spite of the gap between both having grown in recent years. It is estimated that on average consumption exceeds production by more than 45 kg in the course of the entire period. The gap between consumption and production grew larger and was surpassed by 54 kg between the period of 1994-2010; this is contrary to the period from 1980-1993 when the gap was 10 kg below the average of the entire period.

Furthermore, from 1985-1997 86% of consumption was supplied by national production whereas from 1998-2010 coverage decreased to 77% on average. The difference between consumption and production has been compensated through imports mainly deriving from the United States. Defining the dependence index as the national consumption ratio covered by imports, this index has been 14% and 23% for the aforementioned periods.

On the other hand, the Agencia de Servicios a la Comercialización y Desarrollo de Mercados Agropecuarios (Service Bureau for the Commercialization and Development of Agro-livestock Markets, ASERCA for its acronym in Spanish) highlights that around 66% of the maize harvested in Mexico is used to feed livestock (ASERCA, 1997).

From this reason results the relevance in analyzing the determining factors of the supply and demand of maize in Mexico, as well as reviewing the behavior of the market before and after the entry into force of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). There is evidence that this treaty affected the agricultural sector, increasing maize imports.

In 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations proposed the dependency index for the import of grains as one of its food safety indicators, which provides an estimate three times a year and consists in measuring how much of grain imports represent the apparent1 consumption. By utilizing the proposed method to estimate the dependency index of the maize imports in Mexico, in 2011 it can be observed that 35% of maize consumed in the country was imported. In fact, after the trade openness in 1994 and up until 2011, the dependency index ranged around 23%, whereas in the previous period (1980-1993) it was seven points below this value.

Mexico's dependency on maize imports places it in an unfavorable position with regard to exogenous changes. González-Rojas et al. (2011) highlight that currently the production of maize-based ethanol in the United States has intensified; in 2010 it was 116 million tons and for 2020 it is estimated that it will be 140.3 million tons. Following this line of thought, should the maize sown area of the United States be reduced by 10%, the price of imported maize in Mexico will increase by approximately 9%. Both facts will have negative effects on imported maize due to the dependency and vulnerability of the sector with regard to international competition.

The dependency created towards American maize is due in great part to the synchronization of the harvest prices, according to the Sistema de Información Agropecuaria y Pesquera (Information Service of Agro-livestock and Fishery, SIAP for its acronym in Spanish) (2007) in Mexico. Since 1994, the prices were set through the pricing agreement policy; subsequently, in 1996 the rules were modified to pave the way for the policy of indifference pricing. Through this policy, producers sell to the industry based on the international prices and it is the federal government who pays the difference regarding the target price. However, this is equated to the international price of yellow maize number 2, which in the United States is approximately 20% lower than white maize.

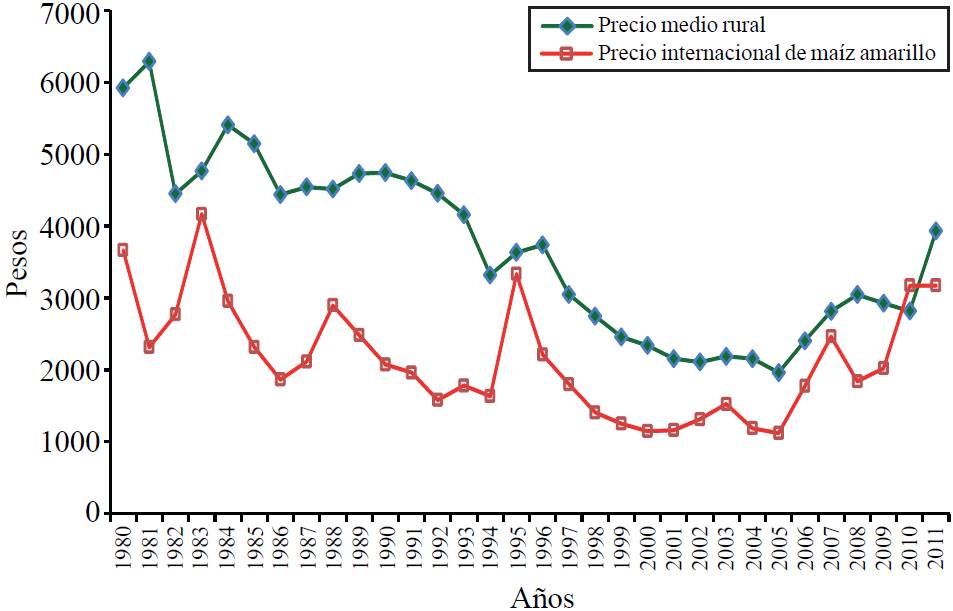

Figure 1 shows that international prices are lower than the rural average price during the period of 1980-2011, but always follow a similar pattern. In this period, the rural average price was 3 685 Mexican pesos per ton, whereas the international price was 2 141 Mexican pesos per ton, and therefore the national price was 1 544 Mexican pesos per ton. The prices and other monetary variables utilized in this study are deflated according to the Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor (Mexican National Consumer Price Index, INPC for its acronym in Spanish) and shown in 2010 values per ton greater than the international price. After 1986, the rural average price started to gradually decrease and subsequently, in 1994, it decreased once more. From 1994- 2011, it can be observed how these prices start to converge so that in 2010 the international price was slightly greater than the registered price in the country.

Sources: rural average price: based on information from the Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP), http://www.siap.gob.mx/agricultura-produccion-anual/; international price: based on information from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdahome.

Figure 1. International price of maize and rural average price in Mexico, 1980-2011.

Saad (2004) describes how since 1990 there has been a constant decrease in the price of maize in Mexico. 1994 is considered a key year because it is the year in which high prices were in effect and the subsidies to producers covered 47% of the produced value. In 1995, with high international prices and the devaluation, the internal prices improved. Subsequently, in 1996-1997 the international maize price maintained a downward tendency. From then on, and without protection plans from foreign trade, the price of maize has fluctuated with the international price leaving the producers exposed to the fluctuations of the international market, every time in a more direct manner.

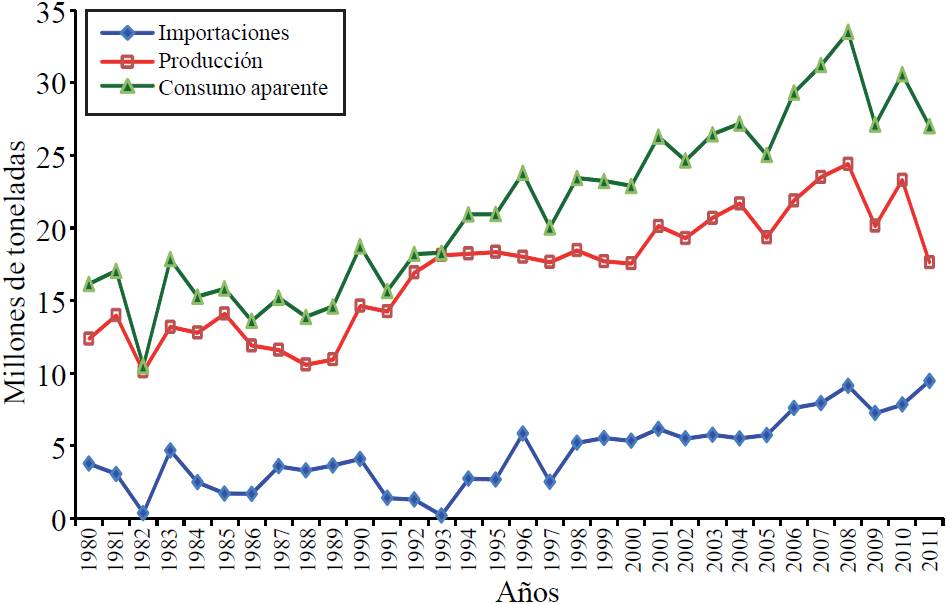

The statistics on foreign trade indicate that the annual average of maize imports was 2.5 million tons in the period of 1980-1994 and 6.2 million tons from 1995-2011. The quantity of imported maize since the enactment of NAFTA until 2011 was greater by 3 million tons on average with regards to the previous period from 1980-1993, year in which NAFTA was signed. Considering the apparent consumption as the result of subtracting exports from production and adding imports, it can be observed that from 1994 the apparent consumption grew more than the national production, generating imports with a growing tendency (Figure 2).

Sources: Imports: based on information from FAOSTAT, http://faostat.fao.org/desktopdefault.aspx?pageid=535&lang=es#ancorG26; production: based on information from the Servicio de Information Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP), http://www.siap.gob.mx/agricultura-produccion-anual/

Figure 2. Imports, production, and apparent consumption of maize, 1980-2011.

Before the growing imports of maize due to an insufficient production of the grain in order to supply national demand, the construction of an agro-livestock and fishery productive sector that guarantees the food security of the country has been implemented as a policy objective in the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo (National Development Plan) 2013-2018 and the Gobierno de la República (Government of the Republic) 2013.

This document has as an objective the determination of the levels of dependency on maize imports through the analysis of supply and demand of this product in Mexico. A system of simultaneous equations is used, which is solved through the two-stage least squares method (2SLS), in order to examine the interaction and impact of variables on the quantity of maize produced and consumed, such as the rural average price of maize, the international price of maize, the input price (urea), income (using the gross internal product as proxy) and the population.

First the concepts of security and food sovereignty are addressed, and the actual policy objective of food security in the country is also studied. Subsequently, through a model of simultaneous equations the main variables that determine the supply and demand of maize in Mexico are identified, and through the estimated values in the system, an index of the dependency on imports is constructed.

Security and food sovereignty

The subject of security and food sovereignty has been widely discussed in Mexico (Urquía, 2014; Rivera et al., 2014). The current food situation is considered a result of the changes and policy objectives that have been implemented since the middle of last century.

The Ley de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable (Law of Sustainable Rural Development) in section XXVII of article 3 defines food security as: the timely supply, sufficient and encompassing foodstuffs to the population. On the other hand, food sovereignty is defined in section XXXII as: the free determination of the country on matters of production, supply and access to foodstuffs for the entire population, fundamentally based on national production (Valero, 2009).

Along the same line, Curiel (2013) explains that Mexico has an important challenge. According to the FAO, a country must be capable of producing at least 75% of the foodstuffs it consumes in order to provide food security to its population. In recent years, Mexico has not fulfilled this recommendation of food security in its entirety.

As part of a review of the policies that have been implemented in different six-year terms, Ortiz et al. (2005) conclude that nowadays there is a foreign dependency on basic foodstuffs. They explain how the change happened from self-sufficiency in the six-year term of López Portillo to sovereignty in the six-year term of Miguel de la Madrid to finally setting food security as a goal in the six-year term of Salinas de Gortari. In this timeline it can be observed how the internal demand for foodstuffs has stopped being self-supplied and has given way to growing imports.

Saad (2004) has studied the behavior of the maize market since the middle of the last century until the beginning of the current century. They examine the difference between supply and demand, finding that from 1950-1965 and from 1991-1993 the production was close to the apparent consumption and foodstuff self-sufficiency could be maintained. On the other hand, from 1965-1969 the production was greater than the apparent consumption of maize; however, they conclude that until 2002 there was a deficit between the production and the apparent consumption, aggravating the situation of food security and giving rise to a foreign dependency with regard to maize due to the growing imports.

Materials and methods

In order to estimate the levels of maize dependency in Mexico during the period of 1980-2011, the functions of supply and demand of maize are determined. In order to fulfill this objective, a model of simultaneous equations is used to be estimated through the two-stage least squares method (2SLS), using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) program.

Specifications of the model

It is important to establish an index that measures Mexico's food dependency with regard to maize. In this study, the import index for grains estimated by the FAO (2010) is used as the dependency index (DI), which is obtained by solving the following equation. The volume of the imported grain is divided by the production plus the imported volume minus the exported volume of the grain:

The model is developed under the hypothesis of a small country, which establishes that the national policies do not affect the international price, and therefore the national companies and consumers must take into account the international price when making production decisions (Suranovic, 2007).

Based on the concept of availability-disappearance balance, it is established that the total availability should be equal to the total disappearance of maize. The total availability is determined by the national maize production plus the imports. The total disappearance of maize should be the sum of the demands for maize, whether for human, livestock and/or industrial consumption, among other uses, plus the quantity of maize demanded for exports.

Where: Qt is the maize production during year t; Dt is the demand for maize in year t; Mt is the maize imports in year t; and Xt is the maize exports in year t.

Given that the demand for this grain is not reported in Mexico, we must then opt for calculating the apparent consumption of maize using the following equation (2):

It is considered that the demand for maize is in function of various factors, as indicated in the following equation:

Where: Dt is the apparent national consumption of maize in year t; PDt is the bid price in year t; PIBt is the gross internal product, utilizing the income in year t as proxy; POBt is the population in year t; and D1 is the dichotomous variable 1 for the NAFTA period (1994-2011), otherwise, 0; εDt is the error term.

It is considered that an increase in the bid price of maize will give rise to a decrease in the demand of maize. Likewise, an increase in the income of the population will impact as a decrease in the demand for maize, as it is assumed that by increasing the income of the population, more products rich in protein will be demanded and therefore more expensive, or with more services included (Garcia et al., 1990). It is considered that the natural growth of the population will increase the demand for maize for human consumption; this being due to the increase in the demand for tortilla and because maize is the main production consumable. In order to observe the impact of the commercial openness in the demand for maize, the dichotomous variable established in the model has a value of 1 for the period in which the NAFTA was implemented (1994-2011) and a value of 0 for the rest of the period (1980-1993), without having a prior expectative for this variable.

According to economic theory, the supply of an agricultural product is determined by factors such as the expected price of the product and the expected price of the consumables utilized. In this way, the supply function is specified as follows:

Where: Qt is the maize production in year t; PEMRt* is the expected rural average price; PEUt is the expected price of the urea in year t; D1 is the dichotomous variable 1 for the period of the NAFTA (1994-2011) and otherwise, 0; εQt is the error term.

Considering a model of simple expectative adjustments, the prices of the same variable delayed one period are utilized as the expected prices. A positive relation is expected between the expected price and the quantity produced. The price of urea (Put) is introduced as a proxy variable to the price of the production consumables, expecting that an increase in the price of the fertilizer decreases the production of maize. SAGARPA (2007) points out that “in the case of commercial consumables, the most important expense is represented by fertilizers, as their expense represents approximately $3,638, equivalent to 45% of the expenditure of the rubric of commercial consumables, which represents 52% of the total cost”. It is expected that for the NAFTA period, variable D1 will have a negative value.

On the other hand, it is considered that the rural mean price (PMRt) in the production of maize is in function of the international price of maize (PIt).

Where: εPMRGt is the error term:

Likewise, it is assumed that the bid price for maize is in function of the rural mean price.

Where: εPDt is the error term:

Once the functions have been estimated, the estimated results of apparent consumption and produced quantity are used in order to calculate the estimated imports (M), with which the index of dependency to maize imports is calculated, considering exports are null:

In this manner, the system of equations is completed.

Based on the results of the Augmented Dickey-Fuller and the Phillips-Perron tests, the non-stationarity of the variables D, Q, PMR, PD and PI in levels is determined, so that for an estimation the first differences of these variables were utilized, represented by DQDT, DQST, DPMRT, DPDT, and DPIT, respectively:

DPMRT=A0+A1*DPIT;

DPDT= B0+B1*DPMRT+B4*QDT_1;

DQDT=C0+C1*DPDT+C4*PIBT+C5*POBT+C9*D 1T;

DQST=D0+D1*DPEMRT+D5*PUT_1+D8*D1T.

The endogenous variables of the system are DT, QT, PMRt, and PDT. The predetermined variables are PIT, QDT_1, PIBT, POBT, PEMRT, PUT, and D1T. The instrumental variables utilized for the estimation of 2SLS are: PIT, PIT_1, PMRT_1, PDT_1, QDT_1, PIBT, POBT, PBT, BCT, PST, D1T, PEMRT, PEMRT_1, QST_1, PUT_1, PFT_1, PST_1. Where PB represents the price of beef; PC represents the price of pork; PS represents the rural average price of sorghum; and PF represents the rural average price of beans.

Results and discussion

In the structural model there is an adjusted R2 of 69% for the demand equation and of 68% for the supply equation. Obtaining the expected signs of the coefficients (Table 1).

Table 1. Estimated coefficients.

| Parameter | Approx estimate | Approx std err |

|---|---|---|

| A0 | -64.1476 | 93.7224 |

| A1 | 0.002102 | 0.1366 |

| B0 | -440.348 | 728.6 |

| B1 | 0.322891 | 0.3873 |

| B4 | 0.000021 | 0.000033 |

| C0 | -6555815 | 10435032 |

| C1 | -651.794 | 679.8 |

| C4 | -0.14348 | 0.1676 |

| C5 | 0.125448 | 0.166 |

| C9 | -961953 | 2930032 |

| D0 | 678404.5 | 732783 |

| D1 | 738.3063 | 827.7 |

| D5 | -53.1333 | 147.6 |

| D8 | -379708 | 972633 |

From these estimated coefficients, the coefficients are calculated in the restricted reduced form of the system of equations, such that each endogenous variable is left in function of the corresponding predetermined variables.

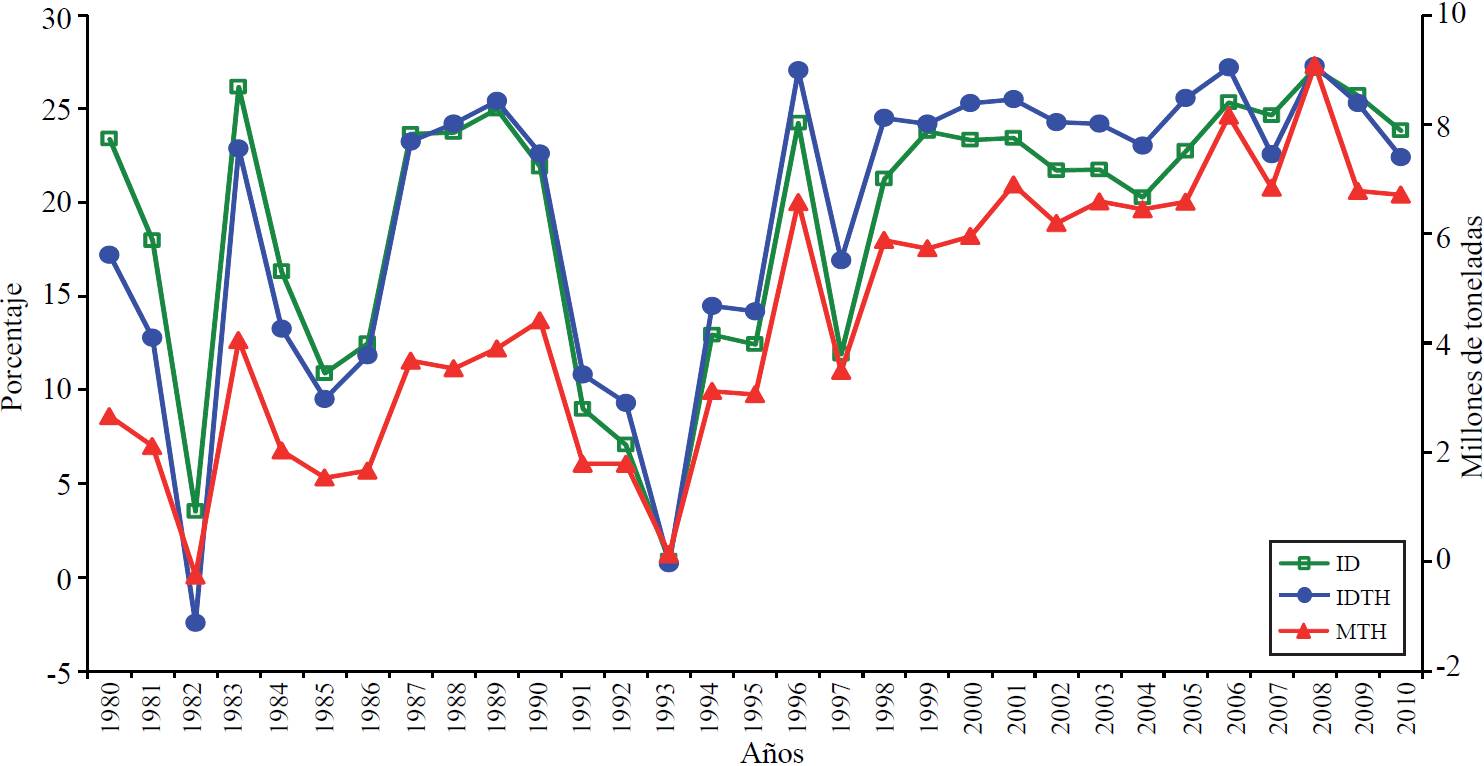

With the estimates of the restricted reduced form and the observed values from 1980-2011, the estimated import amounts are calculated. With these and the estimated quantities of apparent consumption, the dependency indices for said period are finally determined. Figure 3 shows the observed (DI) and the estimated (IDTH) indices, as well as the estimated imported quantities (MTH), where a growing tendency for this index can be observed after 1994.

Conclusions

The index of dependency on maize imports estimated is in general consistent with the index calculated with the observed data on imports and apparent consumption, showing a growing tendency since 1994, thus making the need for forceful measures in favor of food security in Mexico apparent, either through effective incentive programs for production or by establishing a more controlled maize market.

Considering the aforementioned, it is possible to recommend a review of the role that the State has played with regard to the protection of commerce and fostering grain production in Mexico. In this sense, the need for an efficient and effective promoting policy is posed, as well as granting a preferential deal taking into consideration that maize is of great economic importance for a considerable number of homes and also because it is the main traditional foodstuff of the Mexican people.

Literatura citada

ASERCA (Agencia de Servicios a la Comercialización y Desarrollo de Mercados Agropecuarios). 1997. La vanguardia en la producción de maíz en México, Claridades Agropecuarias. 3-15 pp. [ Links ]

Curiel, R. 2013. MasAgro por la seguridad alimentaria y el desarrollo agrícola sustentable en México. Claridades Agropecuarias (México). 237:9-18. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2010. Estado de la inseguridad alimentaria en el mundo. La inseguridad alimentaria en crisis prolongadas. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación. Roma. 64 p. [ Links ]

García, M. R.; García, D. G. y Montero, H. R. 1990. Notas sobre mercados y comercialización de productos agrícolas. 1a ed. Colegio de Postgraduados. México. 437 p. [ Links ]

Gobierno de la República. 2013. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2013-2018. Gobierno de la República. México. 184 p. [ Links ]

González-Rojas, K.; García-Salazar, J. A.; Matus-Gardea, J. A. y Martínez-Saldaña, T. 2011. Vulnerabilidad del mercado nacional de maíz (Zea mays L.) ante cambios exógenos internacionales. Agrociencia (México). 45(6):733-744. [ Links ]

Ortiz, G. A. S.; Vázquez, G. V. y Montes, E. M. 2005. “La alimentación en México: enfoques y visión a futuro”. Estudios Sociales (México). 13(25):7-34. [ Links ]

Rivera de la Rosa., A. R.; Ortiz, P. R.; Araujo, A. L. A. y Amílcar, H. J. 2014. México y la autosuficiencia alimentaria (sexenio 2006-2012). Corpoica Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (Colombia). 15(1):33-49. [ Links ]

Saad, I. 2004. Maíz y libre comercio en México. Claridades Agropecuarias (México). 127:44-48. [ Links ]

SAGARPA (Secretaría deAgricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación). 2007. Evaluación del Programa Fomento Agrícola y Subprogramas Sanidad Vegetal e Investigación y Transferencia de Tecnología 2006. Informe complementario. Estudio de caso sobre la competitividad de las cadenas: maíz y caña de azúcar. [ Links ]

SIAP (Servicio de Información Alimentaria y Pesquera). 2007. Situación actual y perspectivas del maíz en México 1996-2012. SIAP- SAGARPA. México. 131 p. [ Links ]

Suranovic, S. M. 2007. International trade theory and policy analysis. The George Washington University. Disponible en: http://internationalecon.com/. [ Links ]

Urquía-Fernández, N. 2014. La seguridad alimentaria en México. Salud Pública México. 56 suplemento 1:S92-S98. [ Links ]

Valero, F. C. N. 2009. El derecho a la alimentación y la soberanía alimentaria (El caso mexicano). Cámara de Diputados/ Comité del Centro de Estudios de Derecho e Investigaciones Parlamentarias. México. (Serie Verde, Temas Económicos). 91 p. [ Links ]

Received: October 2015; Accepted: January 2016

texto en

texto en