Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.6 no.8 Texcoco Nov./Dez. 2015

Articles

Phenotypic characterization of hybrids and varieties of forage maize in High Valley State of Mexico, Mexico

1Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas-Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Campus Universitario "El Cerrillo". El Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, Municipio de Toluca, Estado de México, México (CPB-TEM).Tel: 01(722) 2965574.

2Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados en Fitomejoramiento, FCAgri, UAEMéx, CPB-TEM. A. P. 435. Tel: 01(722) 2965519. Ext. 148.

3Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, UAEMéx. CPB-TEM. Tel: 01(722) 3966032. (jrfrancom@uaemex.mx; djperezl@ uaemex.mx; mrg@uaemex.mx).

In Mexico, the application of the selection and hybridization have generated increased production of maize grain and Landraces used for double purpose, but there is little information on its potential to develop green and dry matter. This study was conducted in 2013 to identify outstanding forage cultivars for Toluca-Atlacomulco Valley, Mexico. 29 cultivars were evaluated in field under an experimental design of randomized complete block with three replicates per site. The data analysis through the four locations was done as a series of experiments in space. The most important results showed that the best sites for the evaluation of genetic material were Metepec and Tiacaque. The Victoria, H-159 and SBA-470 cultivars were the top fraction of hybridization programs obtained from conventional methodologies and Amarillo Allende, San Cayetano and Portes Gil, and San Cristobal Cacahuacintles Tlacotepec, Blancos Tlacotepec and San Diego, represent the artistic and cultural work of the State of Mexico farmers who, by means of visual mass selection applied to the dimensions of the ear and plant, have increased the productive potential of grain and fodder. The higher yields in green and dry fodder obtained in the most outstanding genetic material are explained by significant increases in the number of leaves per plant, male flowering, plant height, and production of green and dry matter of corn, stalks and leaves. The most outstanding cultivars could be used to derive inbred lines and form new varieties and hybrids forage or allocated to an application program, validation or generation of agricultural technology.

Keywords: Zea mays; multivariate analysis; outstanding forage maize; races of the High Valley on the Center Mexico

En México, la aplicación de la selección e hibridación han generado maíces de mayor producción de grano y los criollos se usan con doble propósito pero existe escasa información sobre su potencial para desarrollar materia verde y seca. Este estudio se realizó en 2013 para identificar cultivares forrajeros sobresalientes para el Valle Toluca-Atlacomulco, México. 29 cultivares fueron evaluados en campo bajo un diseño experimental de bloques completos al azar con tres repeticiones por sitio. El análisis de los datos a través de las cuatro localidades se hizo como una serie de experimentos en espacio. Los resultados más importantes mostraron que las mejores localidades para la evaluación del material genético fueron Metepec y Tiacaque. Los cultivares Victoria, H-159 y SBA-470 constituyeron la fracción superior de los programas de hibridación obtenidos a partir de metodologías convencionales y los Amarillos Allende, San Cayetano y Portes Gil, Cacahuacintles Tlacotepec y San Cristóbal y Blancos Tlacotepec y San Diego representan la obra artística y cultural de los agricultores mexiquenses que, por medio de selección masal visual aplicada a las dimensiones de la mazorca y de la planta, han incrementado el potencial productivo de grano y forraje. Las mayores producciones en forraje verde y seco que se obtuvieron en el material genético más sobresaliente se explican por aumentos significativos en número de hojas por planta, floración masculina, altura de planta, y producciones de materia verde y seca de elote, tallos y hojas. Los cultivares más sobresalientes podrían emplearse para derivar líneas endogámicas y formar nuevas variedades e híbridos forrajeros o destinarse a un programa de aplicación, validación o generación de tecnología agropecuaria.

Palabras clave: Zea mays; análisis multivariados; maíces forrajeros sobresalientes; razas de Valles Altos del Centro de México

Introduction

In Latin America, maize (Zea mays L.) of white and yellow grain are mainly used in making tortillas and animal feed. Feed corn is the main source in the center of Mexico (Antolín et al., 2009), and silage is the most widely used in major dairy areas for its high energy value and high production of green and dry matter (MV and MS), which increased its operating profit (Peña et al., 2010). In Mexico are planted with forage maize 137 432 ha in irrigation and 440 382 ha in rainfed, yielding 33.6 to 47.7 and 17.4 to 20.7 t ha-1 of MV, respectively (SAGARPA, 2014); other irrigation yields vary from 70 to 95 t ha-1 of MV, and more than 20.0 t DM ha-1 (Núñez et al., 1999; Peña et al., 2008; Castillo et al., 2009). Between 1980 and 2010 the growth in the production of forage, milk and beef was 61.2, 43.8 and 40%, respectively, but the last two are below the increase in the Mexican population (45.6%; Brambila-Paz et al., 2014). The average annual growth rate of forage maize in 2012 and 2013 was 4.3 and 8.4, respectively. In the State of Mexico they harvested 26,187 ha and 44.4 t ha-1 obtained MV (SAGARPA, 2014).

Native maize occupy 70 to 80% of the cultivated area in Mexico. In the high valleys of the Central Plateau, formed by the States of Hidalgo, Puebla, Tlaxcala, State of Mexico and 3.5 million ha with Arrocillo Amarillo, Palomero Toluqueño, Cacahuacintle, Cónico and Chalqueño races are planted; the latter two are widely exploited. Mexican farmers have increased production of MV or MS, as well as grain yield and other agronomic traits in its local through visual mass selection and application of technology packages that they have generated (Wellhausen et al., 1951; González et al., 2008; Rocandio-Rodríguez et al., 2014). In the State of Mexico 573 000 ha of corn for grain was planted; the main producing area is the Toluca-Atlacomulco Valley with almost 250 000 ha. The races that predominate are Cacahuacintle, Cónico and Chalqueño used for the production of corn, grain and forage; their performance in the second mode range from 4 to 11.36 t ha-1 (González et al., 2006; González et al., 2008; Reynoso et al., 2014; Rodríguez et al., 2015).

Genetic improvement has been made in the Central Plateau of Mexico, primarily focused on obtaining cultivars of higher grain but have neglected their quality attributes and their forage properties. The Landraces are planted with stubble dual purpose and is an important food species of several units of rural production under dryland conditions byproduct, so special attention should be given to the creation of new materials with desirable characteristics for the production of milk and meat (Muñoz-Tlahuiz et al., 2013; Peña et al., 2012.). Thus, the main objective of this study was to evaluate Landrace and hybrid to identify outstanding forage fraction that allows its recommendation on commercial planting, for breeding and to implement, validate or generate agricultural technology.

Materials and methods

In the spring-summer 2013, the agricultural cycle four experiments were established in Metepec, El Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, Mina Mexico and Tiacaque (municipalities of Metepec, Toluca, Almoloya de Juarez and Jocotitlán), located in the Toluca-Atlacomulco Valley, State ofMexico, Mexico; they differ in geographical location, rainfall, climate, pH, organic matter and soil type (Table 1).

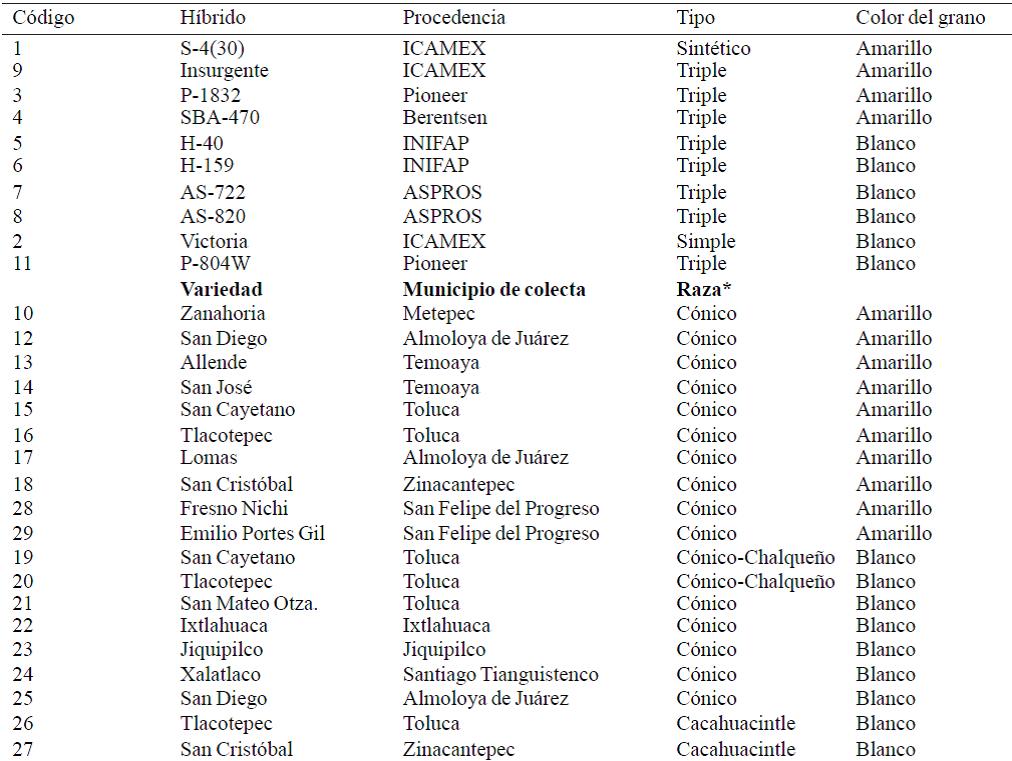

10 hybrid and 19 varieties were used. The former are exploited for the production of grain or dual purpose; four are yellow and six white. The collection ofvarieties was done in Metepec, Santiago Tianguistenco, Zinacantepec, Toluca, Almoloya de Juarez, Ixtlahuaca, Jiquipilco, Temoaya and San Felipe; according to the National Research Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock (INIFAP), 10 yellow cultivars belong to the Cónico race, and nine other grain white, five are Cónico, Two Cónico-Chalqueño and two Cacahuacintle (Table 2).

The 29 cultivars were evaluated in field in an experimental design of randomized complete block with three replicates per location. The plot consisted of three rows of 7 m long and 0.80 m wide (16.8 m 2); the middle row was useful plot (5.6 m 2). Sowing was done manually 11, 18, 23 and April 30 in El Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, Mina Mexico, Metepec and Tiacaque, respectively; irrigation was applied 4-5 days after seeding, except the third location. In each row were deposited three seeds per plant every 30 cm, leaving two plants when the crop was 20 cm (83 333 plants ha-1). The preparation consisted of fallow land, crosses and drag. It was fertilized with 150N-90P-50K: a third of the nitrogen was applied, all the phosphorus and potassium trench and the rest in the second weeding. Weed control was done with tiller and 1.5 L ha-1 atrazine + s-metolachlor in early cultivation mixed in 200 L of water post-emergence. Puffin (Macrodactillus spp.) was controlled with 1.5 L ha1 of malathion. The genetic material was harvested when the grain was doughy.

Male flowering (FM, days from planting to 50% of the plants shed pollen), plant height (AP measured from the ground surface to the insertion of the flag leaf), leaf number was recorded (NH), stem diameter (DT, was measured in two internodes cm below the corn), lodging (Ac, percentage of plants with higher than 45° inclination). AP, NH, DT and AC were determined with eight data. Corn plants in a line of 3 m were used to determine the overall green materials (MVT, t ha-1) and corn with husks (MVE, t ha-1); the fresh weight of stems and leaves was also calculated (MVTH, t ha-1); MVE and 10% MVTH took to dry in an oven at 60 °C with constant humidity and its dry matter (MSE and MSTH, t ha-1) was obtained. MSTH with MSE and total dry matter (MST, t ha-1) was determined.

Combined analysis of variance (Anacom) was generated. Mean localities and cultivars were compared with the Tukey test (p< 0.01) and outputs were obtained with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., version 9.0). The principal component analysis and cluster in the way suggested by Sánchez (1995) and González et al. (2010) were also applied. Anacom squares means were used to estimate the genetic variability of 29 cultivars. The biplot was developed with Microsoft Excel Ver. 1997 to 2003 with scores generated by CP1 and CP2 SAS (1999).

Results and discussion

In the Toluca-Atlacomulco Valley, Mexico localities are very heterogeneous, there is wide diversity between maize and common phenotypic instability. The choice of locations appropriate in the presence of genotype x environment interaction (IGA), it is essential to save time and resources. The wide genetic variation that existed in the 29 cultivars (Tables 3 and 5) is attributed to the differences between the Landraces of the Cónico races, Chalqueño and Cacahuacintle with hybrids INIFAP, ICAMEX, CIMMYT or private companies (Table 2) . The significant IGA was detected in all the variables indicates that most cultivars had specific adaptation being necessary to conduct more tests in time and space to reliably estimate the genetic-statistical parameters to identify a top fraction. The above results are similar to those published by Rodriguez et al. (2002); González et al., (2006); González et al. (2008); Reynoso et al. (2014) and Rodriguez et al. (2015).

Table 3 Mean squares and statistical significance of the values of F for forage production and related variables.

Table 3 Mean squares and statistical significance of the values of F for forage production and related variables (Continuation).

Table 4 Comparison of means for corn forage production and related variables evaluated in four locations in the Valley Toluca-Atlacomulco, State of Mexico.

Medias con la misma letra no son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p= 0.01).

Cuadro 4 Comparación de medias para producción de forraje de maíz y variables relacionadas evaluadas en cuatro localidades del Valle Toluca-Atlacomulco, Estado de México (Continuation).

Medias con la misma letra no son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p= 0.01).

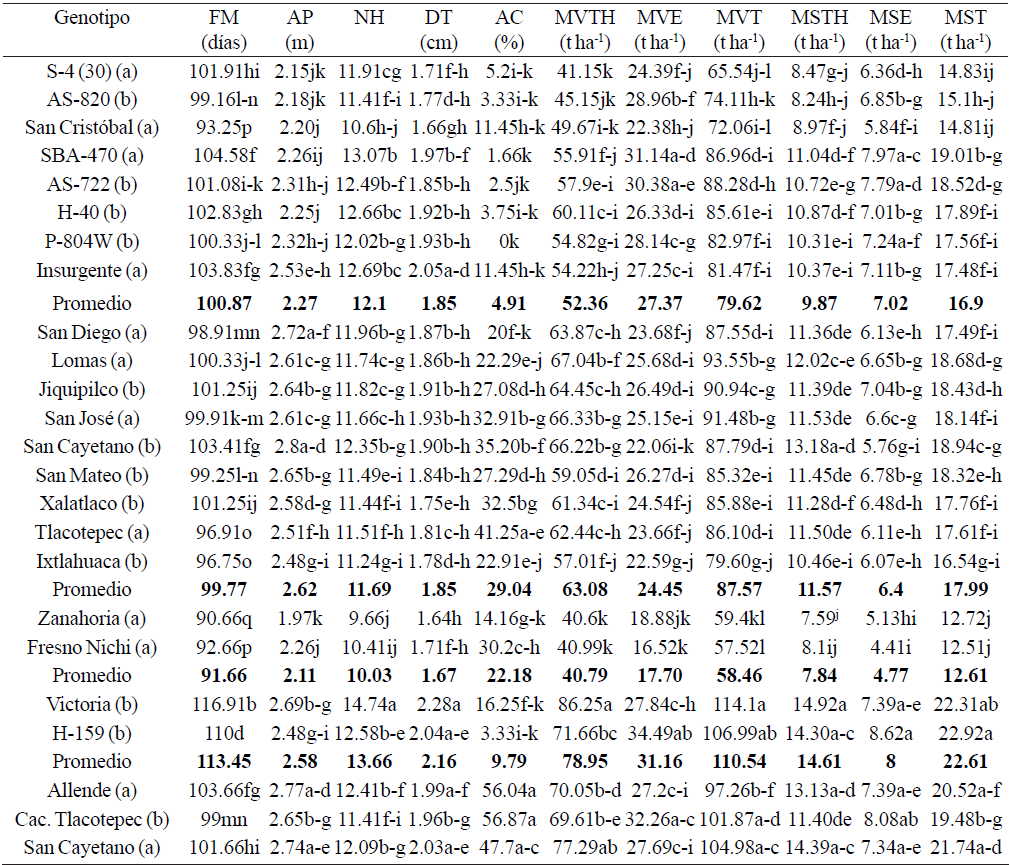

Table 5 Comparison of means between 29 genotypes of maize (Continuation).

Las variables fueron definidas en el Cuadro 3. Medias con la misma letra no son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p= 0.01).

In Metepec, were significantly favored male flowering (FM) and dry corn and green materials, stems and leaves as well as total (MVE, MVTH, MVT, MSE, MSTH and MST). In the El Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, the highest averages were recorded in stem diameter (DT) and MVTH and MSTH. In Mina Mexico had the highest percentages of lodge and in Tiacaque, the plants had larger dimensions, were earlier and performed well in MSE and MST. The best locations for the production of MVT and MST were Metepec and Tiacaque. González et al., (2006), González et al., (2008), Reynoso et al., (2014) and Rodriguez et al., (2015) commented that heterogeneity between localities in the State of Mexico Center is mainly due to differences in soil, altitude, climate and rainfall (Table 1).

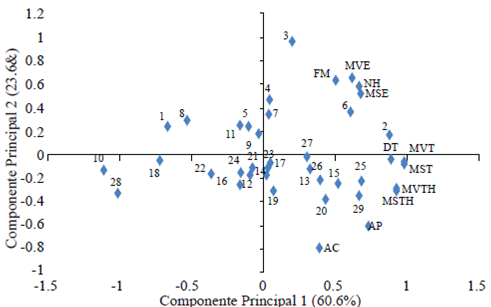

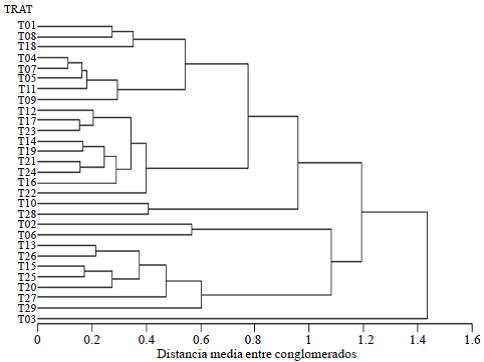

The results shown in Figures 1 and 2 are consistent with those recommended by Sánchez (1995) and Reynoso et al., (2014); when the values of the first two principal components are higher than 70%, the formation of groups of variables or cultivars could be very similar when this multivariate technique is applied together with the cluster (Rodriguez et al., 2015).

Figure 2 Grouping of 29 maizes, considering 11 agronomic variables. Method of unweighted arithmetic average.

In Group 1 (G1), we identify S-4 (30), AS-820, Amarillo San Cristobal, SBA-470, AS-722, P-804W and Insurgent (Codes 1, 8, 18, 4, 7, 5 identified , 11 and 9). With the exception of the third, which belongs to the race Cónico (Table 2), we believe that the rest might have complex racial germplasm CIMMYT. Parents ofH-40 and Insurgent are (CML246x CML242) x M39 and (CML450 x CML461) x CML462 and, in other studies was shown that H-40 was grouped with AS-820 and AS-722 (González et al., 2008; Rodriguez et al., 2015), hence the previously established hypothesis. The outstanding cultivars were SBA-470 and AS-722 with 19.01 and 18.52 t ha-1 of dry matter and 86.96 and 88.28 t ha-1 total green matter (Table 5). González et al. (2007); González et al. (2008); González et al. (2010) and Rodriguez et al. (2015) have emphasized the high potential of AS-722 to produce grain in the central region of the State of Mexico. The use of materials of this group in a plant breeding program could contribute to the diversion of dual-purpose on the biological cycle and intermediate heights plant, resistant to lodging and acceptable biomass production and dry matter.

In group 2 (G2), we detected Amarillo San Diego, Lomas, San José, Tlacotepec and blancos Jiquipilco, San Cayetano, San Mateo, Xalatlaco and Ixtlahuaca (codes 12, 14, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23 are detected and 24); of these, the most outstanding production of green or total dry matter were Blancos San Cayetano (87.79 and 18.94 t ha-1) and Jiquipilco (90.94 and 18.43 t ha-1) and Amarillo Lomas (93.43 and 18.68 t ha-1). According to INIFAP, nine cultivars belong to the Cónicoed or conical-Chalqueño races (Table 2). These results are consistent with those observed in other studies where the cultivar Ixtlahuaca was classified as Cónico (González et al., 2007; González et al., 2008; González et al., 2011). With respect to G1, they were taller and susceptible to lodging but produced more MVTH, MVT, MSTH and MST (Table 5). His collection was made in Almoloya de Juarez, Ixtlahuaca, Jiquipilco, Temoaya, Toluca and Santiago Tianguistenco (Table 2), State of Mexico municipalities Wellhausen et al. (1951) concluded that the diversity of landraces belonging to this region corresponds to the Cónico and Chalqueño races. The crossing of inbred lines G1 and G2 could help the formation of varieties and hybrids of high grain and forage production. Another option we care for this region would become mestizos (line crosses x variety) to try to increase heterosis and adaptability.

In group 3 (G3) were identified Amarillos Zanahoriaand and Fresno Nichi (codes 10 and 28), very early, susceptible to lodging and with smaller dimensions in plant leaves per plant, stem diameter and green matter and dry (Table 5). Cónico both belong to the race and come from the municipalities of Metepec and San Felipe del Progreso (Table 2), a region where Wellhausen et al. (1951) also classified the Cónico race. González et al. (2011) observed that the cultivar Ixtlahuaca, a cónico used as a control, was very close to or grouped with 20 natives collected in El Fresno Nichi, so we suggested that the latter could also belong to this race. Both cultivars could be used in intervarietal crosses with landraces of this or other races to form early varieties.

Group 4 (G4) was formed with Victoria and H-159 (codes 2 and 6), two of the most outstanding cultivars. Both were late (FM), had more leaves per plant (NH), increased stem diameter (DT), and produced more biomass (MVTH, MVE, MVT) and dry matter (MSTH, MSE, MST) that materials G1, G2 and G3. Kennington et al. (2005) suggested that, the production efficiency and quality of forage maize depend mainly on farming. Both cultivars had a lower DT than that recorded by Bosch et al. (1992) on the most outstanding materials, which was 2.33 cm. H-159 produced more dry matter corn but was overtaken by Victoria FM, NH, DT, MVTH, MVE,

MVT, MSTH, MSE, MST (Table 5). Victoria was formed by the ICAMEX lines S4 ofV-18 (Cónico race). Parents of H-159, (M49xM50) x LTVA, were referred by the INIFAP complex germplasm of El Bajio and the Chalqueño race. Cónico and Chalqueño race s are predominant in the high valleys of Central Mexico in over 85% of the maize area in the States of Hidalgo, Puebla, Tlaxcala and State of Mexico (Wellhausen et al., 1951). Both cultivars could be used with some restrictions on the derivation of new inbred lines for purposes of plant breeding or agricultural technology generation.

In Group 5 (G5) we identified Amarillos Allende, San Cayetano, and Portes Gil, Cacahuacintles Tlacotepec and San Cristobal, and Blancos San Diego and Tlacotepec (codes 13, 15, 29, 26, 27, 25, and 20); they were earlier, larger sized plants, more susceptible to lodging and dimensions green dry matter and statistically equal to the G4 cultivars. Tlahuiz-Muñoz et al. (2003) identified landraces with contrasting plant heights in the range of 177-247 cm. The higher elevations of plant are a prerequisite for increased production of green matter and dry matter.

Subedi and Ma (2005) mentioned that, the total number of leaves and specifically those located immediately above and below the ear are the most important to increase grain yield and biomass. The cultivars identified as 15, 20, 25 and 29 surrendered 21.56 to 22.10 t ha-1 MST or 101.81 to 113.29 MVT t ha-1 (Table 5). Wong et al. (2006) and Lauer et al. (2001) concluded that fresh and dry weights of corn with husks (MVE or MSE) and stems (MVT or MST) are the two major components of the total dry matter and green. In this context breeding for the formation of new forage cultivars should focus on obtaining more MVE materials, MSE, MVT, and MST, as a prerequisite for increased production of total dry matter. The seven cultivars belong to the races Cónico, Cónico-Chalqueño or Cacahuacintle and were collected in Temoaya, Toluca, Almoloya de Juarez, Zinacantepec and San Felipe del Progreso (Table 2). Racial classification made INIFAP for materials in this group are consistent with those published by Wellhausen et al. (1951) and González et al. (2008).

P-1832 (Group 6, code 3) had the largest growth cycle, more leaves per plant and zero lodging. These advantages contribute to increased production of green matter of corn, which was higher than the cultivars G1, G2 and G3 but lower than that of G4 and G5. Plant height was as low as that of the materials grouped in G3 (Cuadro5). It is inferred that their parents are different from those that give rise to other cultivars because of its first three contrasting characteristics. In the high valleys of central Mexico late and early frosts they are common, so P-1832 will have disadvantages if planted at a later date to April 15 or towns located above the 2600 m (González et al., 2007; González et al., 2008; González et al., 2011). The intervarietal cross between P-1832 with Amarillos Zanahoria or Fresno Nichi might be promising to generate more early materials, intermediate heights, with the highest number of leaves per plant, stem diameter and more resistant to lodging and MVT productions or perhaps MST identical to those of the groups 4 and 5.

The superiority shown by the cultivars that integrated groups 4, 5 and 6 is attributed to the positive and significant correlation existed between their production of green and dry matter, the rest of the variables evaluated, except for root and stalk lodging (Figure 1). The total green matter production in all cultivars and, especially in the most outstanding was equal to or higher than the average of the State of Mexico, which is 44.4 t ha-1 (SAGARPA, 2014) and were similar to or higher than those recorded by Núñez et al. (1999); Peña et al.. (2008); Castillo et al. (2009), with yields ranging between 70 and 95 t ha-1 of green matter and more than 20 t ha-1 dry matter.

The most resistant materials and root stalk lodging were SBA-470, P-804W, AS-722 and P-1832, with less than 3%. This fraction could be used to improve the poor root system that characterizes the makeup of the High Valley Center Mexico, such as Cacahuacintle, Cónico, Chalqueño, Palomero Toluqueño and Arrocillo Amarillo (González et al., 2008; Reynoso et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2015).

Conclusions

Metepec and Tiacaque were the best places for the evaluation of the genetic material. The cultivars Victoria, H-159 and SBA-470 accounted for the top fraction of the programs obtained by conventional hybridization methods and, Amarillos Allende, San Cayetano and Portes Gil, Cacahuacintles Tlacotepec and San Cristobal and Blancos Tlacotepec and San Diego are the artistic work of the mexiquenses culture of farmers who, by means of visual mass selection applied to the dimensions of the ear and plant, have increased their productive potential in the Toluca-Atlacomulco, Mexico Valley. The increases in the production of green and total dry matter in this outstanding genetic material are explained by significant increases in the number of leaves per plant, male flowering, plant height, and production of green and dry matter, corn stalks and leaves.

Literatura citada

Antolín, D. M.; González, R. M.; Goñi, C. S.; Domínguez, V. A. y Ariciaga, G. C. 2009. Rendimiento y producción de gas in vitro de maíces híbridos conservados por ensilaje o henificado. Téc. Pec. Méx. 47(4):413-423. [ Links ]

Bosch, L.; Muñoz, F.; Casañas, E., y Nuez, F. 1992. Valoración forrajera de 24 híbridos comerciales de maíz de ciclo largo: parámetros de producción de biomasa y de calidad nutritiva. Investigación Agrícola en Protección Vegetal. 7(2):130-142. [ Links ]

Brambila-Paz, J. J.; Martínez-Damián, M. A.; Rojas-Rojas, M. M. y Pérez-Cerecedo, V. 2014. El valor de la producción agrícola y pecuaria en México: fuentes de crecimiento 1980-2010. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 5(4):619-631. [ Links ]

Castillo, J. M.; Rojas, B. A. y Wing Ch, J. R. 2009. Valor nutricional del ensilaje de maíz cultivado en asocio con vigna (Vigna radiata)Agron. Costarric. 33:133-146. [ Links ]

CONAGUA (Comisión Nacional del Agua). 2013. Coordinación General del Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Área Técnica. Departamento de Aguas Superficiales e Ingeniería de Ríos. [ Links ]

González, H.A.; Sahagún, C. J.; Pérez, L. D. J.; Domínguez, L.A.; Serrato, C. R.; Landeros, F. V. y Dorantes, C. E. 2006. Diversidad fenotípica del maíz Cacahuacintle en el Valle de Toluca, México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 29(3):255-261. [ Links ]

González, H. A.; Vázquez, G. L. M.; Sahagún, C. J.; Rodríguez, P. J. E. y Pérez, L. D. J. 2007. Rendimiento del maíz de temporal y su relación con la pudrición de mazorca. Agric. Téc. Méx. 33(1):33-42. [ Links ]

González, H. A.; Vázquez, G. L. M. ; Sahagún, C. J. y Rodríguez, P. J. E. 2008. Diversidad fenotípica de variedades e híbridos de maíz en el Valle Toluca-Atlacomulco, México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 31(1):67-76. [ Links ]

González, A.; Pérez, D. J.; Sahagún, J.; Franco, O.; Morales, E.; Rubí, M.; Gutiérrez, F. y Balbuena, A. 2010. Aplicación y comparación de métodos univariados para evaluar la estabilidad en maíces del Valle-Toluca-Atlacomulco, México. Agron. Costarric. 34(2):129-143. [ Links ]

González, H. A.; Pérez, L. D. J.; Franco, M. O.; Nava, B. E. G.; Gutiérrez, R. F.; Rubí, A. M. y Castañeda, V. A. 2011. Análisis multivariado aplicado al estudio de las interrelaciones entre cultivares de maíz y variables agronómicas. Rev. Cienc. Agric. Informa 20(2):58-65. [ Links ]

Kennington, L. R.; Hunt, C. W.; Szasz, J. I.; Grove, V. and Kezar, W. 2005. Effect of cutting height and genetics on composition, intake and digestibility of corn silage by heifers. J. Animal Sci. 83:1145-1454. [ Links ]

Lauer, J. G.; Coors, J. G. and Flannery, P. J. 2001. Forage yield and quality of corn cultivars developed in different eras. Crop Sci. 41:1449-1455. [ Links ]

Muñoz-Tlahuiz, F.; Guerrero-Rodríguez, J. D.; López, P. A.; Gil-Muñoz, A.; López-Sánchez, H.; Ortiz-Torres, E.; Hernández-Guzmán, A.; Taboada-Gaytán, O.; Vargas-López, S. y Valadez-Ramírez, M. 2013. Producción de rastrojo y grano de variedades locales de maíz en condiciones de temporal en los Valles Altos de Libres-Serdán, Puebla, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 4(4):515-530. [ Links ]

Núñez, H. G.; Contreras, F.; Faz, R. y Herrera, R. 1999. Selección de híbridos para obtener mayor rendimiento y alto valor energético en maíz para ensilaje. Componentes tecnológicos para la producción de ensilados de maíz y sorgo. SAGAR-INIFAP-CIRNOC-CELALA. Folleto Técnico Núm. 4. 2-5. [ Links ]

Peña, R. A.; González, C. F.; Núñez, H. G.; Preciado, O. R.; Terrón, I. A. y Luna, F. M. 2008. H-376. Hibrido de maíz para producción de forraje y grano en el Bajío y la región norte centro de México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 31:85-87. [ Links ]

Peña, R. A.; González, C. F. y Robles, E. F. J. 2010. Manejo agronómico para incrementar el rendimiento de grano y forraje en híbridos tardíos de maíz. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 1(1):27-35. [ Links ]

Peña, R. A.; González, C. F; Núñez, H. G.; Tovar, G. M. R.; Vidal, M. V. A. y Ramírez, D. J. L. 2012. Heterosis y aptitud combinatoria para producción y calidad de forraje en seis poblaciones de maíz. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pec. 3(3):389-406. [ Links ]

Reynoso, Q. C. A.; González, H.A.; Pérez, L. D. J.; Franco, M. O.; Torres, F. J. L.; Velázquez, C. G. A.; Breton, L. C.; Balbuena, M. A. y Mercado, V. O. 2014. Análisis de 17 híbridos de maíz sembrados en 17 ambientes de los Valles Altos del centro de México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 5(5):871-882. [ Links ]

Rocandio-Rodríguez, M.; Santacruz-Varela, A.; Córdova-Téllez, L.; López-Sánchez, H.; Castillo-González, F.; Lobato-Ortiz, R.; García-Zavala, J. y Ortega-Paczka, R. 2014. Caracterización morfológica y agronómica de siete razas de maíz de los Valles Altos de México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 37(4):351-361. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, F. I.; González, H. A.; Pérez, L. D. J. y Rubí, A. M. 2015. Efecto de cinco densidades de población en ocho cultivares de maíz sembrado en tres localidades del Valle de Toluca, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 6(8). [ Links ]

Rodríguez, P. J. E.; Sahagún, C. J.; Villaseñor, M. H. E.; Molina, G. J. S. y Martínez, G. A. 2002. Estabilidad de siete variedades comerciales de trigo (Triticum aestivum L.) de temporal. Rev. Fitotec. Méx. 25(2):143-151. [ Links ]

Sánchez, G. J. J. 1995. El análisis biplot en clasificación. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 18(2):188-203. [ Links ]

SAGARPA (Secretaria de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación). 2014. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP)- Anuario Estadístico. http://www.siap.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute). 1999. User's guide: Version 9. Cary, NC. USA. [ Links ]

Subedi, K. D. and Ma. B. L. 2005. Ear position, leaf area and contribution of individual leaves to grain yield in conventional and leafy maize hibryds. Crop Sci. 45:2246-2257. [ Links ]

Wellhausen, E. J.; Roberts, L. M. y Hernández, X. E. 1951. Razas de maíz en México, su origen, características y distribución. Oficina de Estudios Especiales. Secretaria de Agricultura y Ganadería. Folleto Técnico Núm. 5. México, D. F. 237 p. [ Links ]

Wong, R. R.; Gutiérrez, R. E.; Rodríguez, H. S. A.; Palomo, G. A.; Córdova, O. H. y Espinosa, B. A. 2006. Aptitud combinatoria y parámetros genéticos de maíz para forraje en la Comarca Lagunera, México. Universidad y Ciencia. 22(2):141-151. [ Links ]

Received: July 2015; Accepted: November 2015

texto em

texto em