Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.5 n.spe9 Texcoco Sep./Nov. 2014

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i9.1059

Articles

Potter task in San Felipe Cuapexco, Puebla and its potential for value-added production

1 Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Puebla. Carretera Federal México-Puebla km 125.5 (Boulevard Forjadores), Santiago Momoxpan, Municipio de San Pedro Cholula. C. P. 72760 Puebla, México, A. P. 1-12 Col. La Libertad Tel: 01 (222) 2 85 00 13, 2 85 14 48, Fax 2 85 14 44.

2 Universidad Politécnica de Puebla, México.

In order to known the pottery work, to identify its troubles and start actions leading to improve the quality of this kind of craft (particularly the production of rustic (comales) in San Felipe Cuapexco, Puebla, this work applied elements of participatory action research in combination with some quantitative methods. With the consensus among participants it was conducted a teaching- learning process in order to appropriate the techniques to pasting stickers to the polyoleo and also by hand painting in acrylic on the rustic comales. During this process, the potters ‘willingness to work together as a team was increased, beside the communication and the assistance among them’. The craftsmen who produced throughout all the year and have the higher production capacity were the most active participants. It was found that an alternative to increase the griddles or comales value is through painting and decorating them, diversifying their use as decorative crafts items, expecting to earn up to four times in contrast with its regular price as rustic comales.

Keywords: acrylic painting; comales; participative action research; pasting stickers to polyoleo; pottery; rustic

Esta investigación aplico elementos de la investigación acción participativa en combinación con métodos de la investigación cuantitativa, para conocer el quehacer alfarero, identificar su problemática y emprender acciones de mejora en la actividad productiva de alfarería (comales rústicos), en San Felipe Cuapexco Puebla. Con el consenso entre participantes se llevo a cabo un proceso de enseñanza aprendizaje en diversas sesiones para apropiarse de técnicas de pegado de cromo al polióleo y pintura a mano en acrílico sobre comales rústicos. Durante este proceso se fortaleció la capacidad de trabajo grupal, la comunicación y ayuda entre los participantes. Los artesanos que producen todo el año y tienen mayor capacidad productiva fueron los más participativos. Se detectó que una alternativa para generar valor a los comales es a través de la pintura y decoración, para diversificar su uso hacia artículos decorativos-artesanales, ya que por ellos pueden llegar a pagar hasta cuatro veces más que su precio como comal rústico.

Palabras clave: alfarería; comales rústicos; cromo al polióleo; investigación acción participativa; pintura en acrílico

Introduction

At present and from the perspective of the observer, the Mexican rural sector resembles a landscape interrelated pressures that limit the development of productive activities and therefore the presence of large groups of population living in poverty and marginalization. For many authors, this sector is directed by inefficient public policies that ignore the peculiarities of the territories, groups and individuals; where government actions are reduced to low impact assistentialist activities, especially unaware of the capabilities and potential of rural groups subjecting them to processes of economic and social exclusion without recognizing the true value of the goods offer by them even the knowledge necessary to their use and/or production

Nevertheless, in the Mexican rural environment, there are many products commercialized in the industrial market based on the local knowledge registered in them and that expressing a wealth of non-valued and not recognized knowledge involved in the profits obtained from them.

One of these activities is the pottery, than as in the griddles and jars potters of San Felipe Cuapexco, have been marginalized from the transformation processes, which has led to an unprofitable activity and with an uncertain future given the magnitude of the restrictions that they faces.

Despite the situation indicated, pottery is an important activity that contributes to the subsistence of the local families (providing money to get food, cloth, water, electricity and even to buy some items for their agricultural activities), also strengthens the coexistence and the development of productive capacities of the family, enhancing their cultural identity and self-confidence to generate income, without implying the neglect of their responsibilities at home and in the plot.

Due to the relevance of pottery for the San Felipe Cuapeaxco families and recognising that the information about this topic is not enough to make transformation suggestions, the present research stablished as its main aim to establish an improvement proposition located in a research line leading to increase the value of their crafts with enough both cultural and economic viability to be developed by potters as an alternative to the traditional sale form of their product. The study addresses the work of the potters of San Felipe Cuapexco, from some elements of participatory action (PAR) research in combination with quantitative elements, about what they are, what they have and what they do to self-generated income and continue with the vision to remain in their community

Methodology

Recognition of the research action area

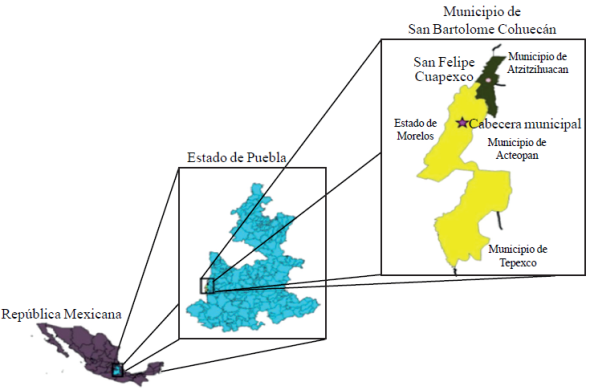

The community of San Felipe Cuapexco, belongs to the Cohuecan municipality which is located in the west central part of the state of Puebla, its geographical coordinates are 18° 41' 4’' and 18° 50' 48' north latitude and meridians 98° 39' 42’’ and 98° 44' 8’' west longitude. The community is located four kilometers from the county seat. Bordered on the east by the municipality of Acteopan, Puebla; while to the west, south, north and west borders the state of Morelos (INAFED, 2013) (Figure 1).

The community has a total population of 629 persons, of which 298 are men and 331 are women; the total population is distributed in 155 houses and has a high level of marginalization and low levels of formal education (CONAPO, 2010).The main productive activities include primary production sector such as corn, beans, peanuts, sorghum and amaranth; beside the backyard is used to establish ornamental plants, vegetables, herbs and seasonings. In livestock predominates the use of fowls, pigs, sheep, goats and working animals (horses) which are raised in the backyard under a “rustic” or traditional system with a low number of animals per species. An activity of great importance is clay pottery for manufacturing griddles (comales), pots and jars, which is developed by more than 80% of the families in the community.

Methodological procedure established

As mentioned above, the present research lies in the scope of participatory processes so it takes elements of the proposed participatory action research developed by Yopo (1981), in combination with elements of quantitative research such as census, survey, semi-structured and in-depth interview.

The general process of this research was conducted in seven iterative phases grouped in two steps described below:

First stage: previous stage

Phase 1. Establishment of the working group: consists of one female master's student, five researchers (both sex) from the Postgraduate College in Agricultural Sciences, Campus Puebla and from the Polytechnic University of Puebla, specialists in the fields of economics, rural development and security food.

Phase 2. Documental review: it was made a search and review of articles and books on specific cases of pottery production in Mexico and other countries; also was reviewed some other books about participatory methods in order to know the theoretical approaches used, methods of study, variables analyzed and results.

Second stage. Participatory research

Phase 3. Approach with potters by three-way contact: 1) workshops and meetings between the team researchers and the family members of the working group "New Sunrise" of the community; 2) informal presentation with potters from the community; and 3) a census of potters.

Phase 4. Analysis of pottery production: through a participatory diagnosis, conducted in three sessions, inquired about the pottery activity and its problems; and visits to the workshops and exploring the community.

Phase 5. Determine course of action: among the methodological tools used, highlight: the problems identification, the prioritization of the same and the FODA analysis. From a collective analysis and the evidenced interest by the majority of the handycraftwomen it was determined that the line of action leading to add value to the griddles(comales) would be the transformation of they into a decorative-crafted objects by painting in acrylic and pasting stickers to polyoleo.

Phase 6. Participatory work: once defined the main line of action, a teaching-learning process, conducted in seven sessions during the months of July to November 2012, in the auditorium of the community was established in response to the request made by the female potters who commented that "it was better to work in a neutral place like the auditorium and not in the house of one of them, to avoid troubles". It began with the teaching of art to pasting stickers to the polyoleo through a female expert on the subject, then, by the approach of learning by doing, with the support of videos and handbooks, artisans of both sex learned the art of painting acrylic by hand. During all sessions the develop of skills was promoted through participation, communication and support among participants, free to decorate the comal from their own perspective, without any pressure and using their personal creativity. At the end of each session the quality of the work done was valued.

At the same time, the potters participated in craft fairs and exhibitions, with the purpose of publicizing their products and encourage artisans to continue developing their skills. These events were utilized to study the perceptions of consumers about the product and the price to pay, based on Kitelab (2009), from a survey conducted by the artisans themselves.

Phase 7. Feedback: after six months of participatory work, the female potters proposed to hold a meeting to discuss the workflow, based on the experiences of the teaching-learning process established and participation in fairs and exhibitions. At this meeting the women decided to make adjustments to two aspects of workflow: a) work in subgroups; and b) focus exclusively on the art of hand painting. The group was divided into three subgroups and were endowed with the materials needed to continue painting and decorating the comales. They have had informal meetings until November 2013.

Results

In this section shows the most important results of the second stage of this work called about the participatory research; particularly in relation with: phase 4. Analysis of pottery production; phase 5. Determination of the line of action; phase 6. Participatory work and phase 7. Feedback; recognizing that their development was not linearly, but rather through an iterative process during the period of the investigation.

Comales production in San Felipe Cuapexco

The pottery has been practiced in the community for 200 years, which has generated a vast experience in the production of griddles (comales). In relation with the local people experience in this activity, the census found that 5% of the potters have more than 61 years, 33% have about 30 years, 40% between 16 and 29 years and 22% have less than 15 years in this activity. In many household pottery is practice in function of their agricultural work, this coincides with the statements made by Morales (2011), Moctezuma (2010) and Turok (2006). In the community of Cuapexco during sowing season of the main extensive crops, griddles making stops. However, 34% of the potters does not interrupt the pottery activity because it is their core business and do it all year round. During the dry season, the female potters spend 4 to 8 hours per day making comales without neglecting housework.

It is noteworthy that 79% of the potters is dedicated exclusively to make comales, 8% makes pots, 9%, produces both products (griddles and pots), and 2% makes comales and clay figures. Specializing in making comales have been given because it allows time available for performing other activities (agriculture, backyard and other works) beside because this activity can be interrupted; contrary to the manufacture of jars which production involved several hours of continuous labor and should not be interrupted because the necessity to assembly several parts. Besides the jars are deprecated in the region and therefore its processing and marketing has declined.

Rating pottery production in the lifestyle. For 51% of FPU (familiar production units) practicing pottery consider this activity as important as agriculture, because it is an activity that adds significant economic resources to the household economy and according to their own opinions of female potters and male pottery "with a single productive activity they could not survive "; while for 34% of potters is more important agriculture; against 12% of them consider most important pottery because it generates more income and 3% consider most important other kind of work in relation with the pottery.

For women, the work invested in the manufacture of comales has allowed them to attend their children even when they are single or widowed mothers, and for those living with their husbands, selling comales adds economic resources to their families. As themselves indicate "to make comales always lets you eat, otherwise, you not eat".

Comales production process. As described by Morales (2011), Mendez (2008), Osorno and Nayra (2008), the comales production process are divided into the following three phases:

a) Obtaining and preparing the clay. It is get for free from the "mine clay" located in the site called Tlaxtlala in the oaks hill that is less than a kilometer from the community. Usually the family head (husband) is the person in charge of removing the mud with picks and shovels and haul it home. The clay obtained is dried on a canvas or on the pavement of the street, at the same time large clods are fractionated hitting them with a stick or leave the cars and people tread down it, the stones are also removed in order to grind the clay with a hammer mill. During grinding two types of clay are combined in order to obtain a clay mass more pliable. Another available resource and that is required to make comales is sand, which is obtained from the river that runs through the community. Inputs such as firewood and paint come from other regions and are purchased by potters because there are people who take them to the community.

The preparation of the mass of clay is a work done mainly by women. They prepare certain amount of mud: combine water and clay on top of a plastic or on a wheelbarrow and with his hands they made the mix. Once the mix of clay is ready, it is placed in the forms of balls or sticks into plastic bags in order to ferment overnight and without lose its original moisture content.

b) Molding. The next day, after done housework, women potters start working with the clay: in a table of stone or wood, spread fine sand that serves as nonstick, place the ball of clay and with the help of a special stone (sprinkling of dry clay powder) they extend and flatten the mass of clay. When the piece has a thickness of one centimeter and diameter according to the size indicated to be obtained, it is moved to the mold in order to sanding it with a wet stone turning it until a concave shape printing the figure of a cock. Finally with a thread, the edge protruding mold is cut and polished with a wet rag. After molding the griddle, it is carried to a shaded place (sometimes under a tree) in order to reduce its moisture content and after some minutes move to sunny place to accelerate the drying time is reduced. When the griddle is already aired, it is painted with a red color made with red clay.

c) Baking product. The baking is done during the evenings and takes about 2 or 3 hours. Ovens are made with adobe brick or block and are built by the potters themselves and their capacities vary depending on how many comales want to burn: 70, 100 or 200 griddles.

Rustic comales marketing. The rustic comales produced in Cuapexco have the characteristic of being resistant to fire and have a shelf life of up to one year. Most potters sell their product to intermediaries from other communities and regions or even from the same community, this agrees with Fernandez (2003), which mentions that the main form of marketing earthenware is through intermediaries. Only a few people from other communities or regions (Hueyapan, Zacualpa and Cuautla, Morelos state, and San Juan Amecac, Cohuecan and Atlixco, Puebla State) offer their products directly to the consumers door to door, getting until 35 pesos for large comal.

Production costs. The majority of potters unknown both costs and quantities of items used in comales production, for that reason it was estimated the cost of production referred to 150 comales in the FPU of Don Ildefonso, based on the production of large comal. This could be a first approximation of raw materials quantities are involved and have a reference for the analysis of production costs to other potters. For determining it, the price of clay, water, wood, sand and labor (Table 1) was added. Artisans generally only consider the costs involved in the purchase of inputs such as wood, paint, water, and ground transfer clay and do not take into account their investment work, neither the price of clay and sand, in the case that these materials must be buy. From an analysis of 30 FPU producers of comales, and with reference to the production of 100 griddles, it was determined that the average cost is $1 171.14 at a unit cost of $11.7.

Table 1 Costs involved in the production of 150 griddles.

| Concepto | Cantidad | Costo | |

| Materia prima | Arcilla | 8 costales | $ 240.00 |

| Arena | 25 kg | $ 3.40 | |

| Agua* | 250 litros | $ 1.00 | |

| Pintura* | 1 medida | $ 8.00 | |

| Mano de obra | Extracción de arcilla | 8 costales | $ 40.00 |

| Preparación del lodo | 8 costales | $ 60.00 | |

| Moldeado | 150 comales | $ 960.00 | |

| Extracción de arena | 25 kg | $ 30.00 | |

| Secado y molida de arcilla | 8 costales | $ 20.00 | |

| Horneado | 150 comales | $ 120.00 | |

| Gastos indirectos | Traslado de arcilla* | 8 costales | $ 27.00 |

| Leña* | 180 kg | $ 360.00 | |

| Molida de arcilla* | 8 costales | $ 30.00 | |

| Total | $ 1 899.40 | ||

| Gasto percibidos por el alfarero* | $ 426.00 |

*Para Don Idelfonso el costo de producción lo refiere a $426 pesos, generándole una ganancia aparente de $1 473.40, si vendiera todos los 150 comales que produce con intermediarios.

Fuente: elaboración propia con información de entrevista a profundidad.

The family production units (FPU) with more productive assets (mill, oven and wheel) have a higher production capacity. Those with the highest assets (10 to 14.6) produce an average of 2 350 comales per year, while those with a lower rate of assets (0 to 3.8) produce an average of 1 572 comales per year. It also noted that production costs are lower for FPU that occur throughout the year, with the highest average assets and greater capacity for baking parts (Table 2); while for those who produce few months have the highest cost of production.

Table 2 Costs of production, production period and baking capacity.

| Todo el año | Octubre- mayo | Enero-mayo | |

| Costo de producción promedio | $ 1 041.47 | $ 1 136.69 | $ 1 247.67 |

| Capacidad del horno promedio | 137.78 piezas | 129.75 piezas | 114.44 piezas |

| Índice de activos promedio | 9.83 | 9.5 | 9.33 |

Fuente: elaboración con información de 30 hogares alfareros.

Determining the action line

To determine the action line, it were conducted three participatory workshops where artisans problems faced, highlighting in order of importance: the low price of their products; the absence of an exclusive workshop for activity; kneading the mud as it is a task that requires a lot of physical effort and finally the lack of firewood as an available resource in the community.

The FODA analysis indicated that the main weaknesses of the production and constrain it are those related with the drying process, the lack of regulation of the temperature in the ovens, lost by broken during baking griddles, lack of support that can get the potters and uncontrolled extraction of the raw materials. Furthermore, within the threats that stand in the production of comales are some neighboring communities that have usurped the image of the cock, distinctive Cuapexco potters and the presence of intermediaries who buy the production driving prices to their own convenience.

Nevertheless each problem was analyzed in depth and possible proposed solutions were identified, in this occasion we only describe the proposals made to the problem of low products prices, as this was the one that marked the group's future actions. The proposals were aimed at: 1) make other products with clay like flat figures or pots; 2) add features to rustic comal to increase their economic value; 3) obtain trademark for the cock; and 4) organize to establish direct sales channels to consumers in other towns or other municipalities.

After analyzing the information among participants (potters and researchers), it was determined that the main problem to be faced is the low economic value of their comales, defining the painting and decorating them to transform their use in decorative-craft would be an alternative to develop, as it is presented as the most viable from an economic, social and cultural vision of the potters and the working group, because it requires a low economic investment, respects the activities and times of potters and seeks to capture and rescue the culture of the community. Further it was argued that the comales that would be decorate must be of stove size, it is, three times smaller than the largest comal.

Participatory work: teaching-learning process

After identifying the line of action, this work proceeded to establish a teaching-learning process to add or change features of the rustic comales (Figure 2). The learning sessions involved a total of 35 people, 8 of which were girls, 5 boys, 17 women over 15 years and 5 men over 20 years. The presence of people was very different: 40% of participants attended constantly, including young women between 16 and 40 years, girls between 7 to 14 years, and a man of 23 years old.

Women and girls who attended constantly worked with group integration, collaborative sense and good communication, helping between them when there was a complication in the development of his painting. Under this form of work several female potters discovered their own skills and qualities to paint, as they are not believed capable of doing the job, in many occasions they were surprised by the work themselves did and were motivated to do their best work.

The process of teaching-learning established in this work encouraged the development of capacities, leading to the established by Reason and Bradbury (2008), “to generate valuable knowledge to transform reality”, which is found in the following opinions of some females potters.

A benefit not covered by this participatory process, expressed by the participants was "living in a different home space cleared and removed the stress of the daily chores at home". During the learning sessions there were two people who liked the work and made 30 comales orders eachm such sale motivated to continue painting and improve their work.

Based on the characteristics of their participation, female potters can be considered as entrepreneurs, therefore, as exemplified Okhomina (2010) it is pertinent to analyze the characteristics of production context. The artisans who had a constant participation came from households with higher production capacity in pottery, both by a greater asset availability and frequency of production.

Relevant aspects involved in the decorated comales selling. As important element to identify whether it was on the right track with respect to market for new products the potters participated in various marketing events. Several members of the group attended three craft fairs on different dates, one in the town of Zacualpan of Amilpas, Morelos (23 and 24 November 2012), and two in Puebla capital on 14, 15 and 16 December 2012 and April 19-21 of 2013 (Figure 3). During the exhibition, 95% of the griddles were sold. During these events valuable consumer opinions were rescued and a study was conducted through surveys to study the perceptions of current consumers and potential consumers. It was observed that hand painted comales (acrylic technique) had more acceptance among the survey of people who like to buy crafts and about the designs were preferred those with landscape paintings of nature (22.4%), rustic landscapes (17.9%) and flowers (14.9%).

The consumer ratings expressed in money on what they can or are willing to pay for a product is certainly related to their income, what they like, with the genre belongs (Table 3), and some other features. In the analysis by occupation, it was observed that to be a housewife or have some other activity as an employee or trader does not determine a trend of things about the amount to pay for the decorated comales.

Table 3 Price that can paid for the potential consumers.

| Variable | Grupo | Promedio | Estadístico t | Significancia |

| Género | Masculino | 74.5 | -2.395 | 0.022* |

| Femenino | 52.8 | |||

| Ocupación | Ama de casa | 51 | -0.731 | 0.471 |

| Otros | 55 | |||

| Técnica de pintura | Pintura en acrílico | 70 | 1.95 | 0.05 |

| Cromo al polióleo | 53.8 | |||

| Por su referencia | No los ha visto | 55.2 | 0.736 | 0.467 |

| Si los ha visto | 61.4 | |||

| Ingreso | 3 000 a 6 000 | 53.5 | -2.037 | 0.049* |

| 7 000 a 12 000 | 72.5 |

* Puesto que la hipótesis nula (Ho) a contrastar: No existencia de diferencia significativa entre promedios. Por tanto, si el valor de la probabilidad (p< 0.05) se rechaza Ho.

Fuente: elaboración propia con base en el sondeo de opiniones a 42 consumidores potenciales en las ferias Agro-Artesanales.

The variables that make an effect as to pay a higher price for the painted griddles are: having higher income and being female. Although the evaluation that gives the consumer about the type of hand-painted comales compared with those that have stickers, does not meet the rule of significance, it can be said that it is important the difference between what consumers can pay, as it is willing to pay an average of 70 pesos for this product. This agrees with the point made by (Ramos et al., 2000; Fernandez, 2003; Hernández et al., 2005; Herrera, 2007; García, 2009) in the sense that it a good idea to improve the handcraft quality to expand its market.

Reedback

In relation with the subgroups formed, only one of them could continue painting because the female artisan who leads the group has managed been fair and equitable. The subgroup consists of four members, in terms of quality have improved their work (Figure 4), have sold comales sets through assignments and also have to give them as memories at social events, which have been well received and good comments. It is important emphasize that the female potters have become more open, participating in exhibitions and events to promote their products, have developed confidence (formerly dared not speak in public because they were worth it). On the other hand, they are still in search of a better market, at the same time some of them are concern to teach painting to other female potters who want to learn.

The second group could not continue working together because the female artisan who led the group has problems with her husband and did not allow her to continue painting; also there was a friction of interests between her and another group member. The group consisted of five members. Although not allowed to continue working in a group, the material was available for them to work at home and they did, but the subgroup is dissolved because a member is moved to another town and another member was in his last months pregnant and had to care for her daughters of one and four years. Currently the members of this team practice very little the paint on griddles.

The third group was formed with eight members and had had previous training about comal paint. This group neither could follow working, because three of its members are elderly and had no patience for the details of the painting, the other members have more activities at home that we not allowed them to continue practicing painting, in addition to them griddles making is not one of its main activities.

Conclusions

The application of participatory processes and in particular some elements of the PIA involved in this study was able to generate and implement a focused add value to the rustic griddles, through painting and decorated alternative; beside this activity allowed to the female artisans to develop skills that made them feel better about themselves and improved the quality of its handicrafts.

The features added to rustic comales represents a viable option for generating added value in this kind of handcraft, as was observed in this investigative process the price the consumer can pay by artistic comales hand painted landscape is four times more than the price that artisans receive in selling rustic griddles. Thus it is possible to earn a better income and also is an activity that fits the lifestyle of potters without changing the essence of their original handmade products, as suggested by Hernández et al. (2006), when working with artisans must take into account the traditions and culture of the artisans.

Literatura citada

Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO). 2010. (consultado enero 2014). http://www.conapo.gob.mx . [ Links ]

Fernández, R. C. 2003. Comercialización de alfarería tradicional del Municipio de Zautla, Puebla. Tesis de licenciatura. Facultad de economía. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP). [ Links ]

García, A. V. H. 2009. Los alfareros del Barrio de la Luz de la ciudad de Puebla. Una tradición en vías de extinción. Tesis de Licenciatura. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP). [ Links ]

Hernández, G. J. P; Domínguez, H. M. L. y Caballero, C. M. 2005. Innovación de producto y aprendizaje dirigido en la alfarería en Oaxaca, México. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 11: 213-228. [ Links ]

Hernández, G. J. P.; Espinoza, R. C. R. y Domínguez, H. M. L. 2006. La capacitación en la producción alfarería de Santa María Atzompa, Oaxaca. Naturaleza y Desarrollo. 4:43-54. [ Links ]

Herrera, M. B. 2007. Patrimonio y cultura popular. El caso de las artesanías de barro policromado de Izúcar de Matamoros en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Tesis de Licenciatura. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y Desarrollo Municipal (INAFED). 2013. (consultado enero, 2013). http://www.inafed.gob.mx . [ Links ]

Kitelab, 2009. Plan de vuelo, guía práctica para la investigación de mercados en Latinoamérica. México. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP). 230 p. [ Links ]

Méndez, G. M. 2008. El arte de la alfarería lenca. Manual práctico. Edición asociación exterior XXI. Madrid, España. [ Links ]

Moctezuma, Y. P. 2010. La mujer en la alfarería de Tlayacapan, Morelos: retrospectiva etnográfica de un oficio. Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital. 6:223-246. [ Links ]

Morales, M. J. J. 2011. Producción cerámica en el suroeste del Bajío. Centro de estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos. 25-39 pp. (consultado marzo, 2013). http://cemca.org.mx/trace/TRACE_59/Morales_T59.pdf . [ Links ]

Okhomina, D. A. 2010. Entrepreneurial postures and psychological traits: the sociological influences of education and environment. Research in higher Education Journal. Fayetteville State University. [ Links ]

Osorno, P. A. B. y Nayra, M. W. 2008. Validación de un Eco-horno para la producción alfarería y evaluación de su eficiencia en cuento a al uso de leña en el municipio de Ojojona, Departamento de Francisco Morazán, Honduras. Proyecto: fortalecimiento de los recursos naturales en las cuencas de los ríos Patuca, Choluteca y Negro forcuencas HND/B7-310/07/319. [ Links ]

Ramos, M. D. E.; Tuñón, P. E. y Carderón, C. A. 2000. Artesanías, una producción local para mercados globales. El caso de Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas México. In: seminario Internacional Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. 2008. The SAGE handbook of action research participative inquiry and practice. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Torres, R. R. 2011. Características sociodemográficas y estrategias de sobrevivencia de unidades domesticas campesinas en tres localidades del municipio de San Pedro Cholula, Puebla. Tesis de maestría. Colegio de Postgraduados en Ciencias Agrícolas. 96 p. [ Links ]

Turok, M. 2006. Como acercarse a la artesanía. México. Plaza y Valdez y SEP (Ed). Tercera edición. 200 p. [ Links ]

Yopo, P. B. 1981. Metodología de la investigación participativa. CREFAL. Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, México. 54 p. [ Links ]

Received: January 2014; Accepted: August 2014

text in

text in