Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.5 spe 8 Texcoco 2014

Investigation notes

Cardinal temperatures and germination rate in husk tomato cultivars

1Postgrado en Botánica, Campus Montecillo- Colegio de Postgraduados. Carretera Federal México-Texcoco, km 36.5, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. C. P. 56230. Tel: 95 20200. Ext. 1318.

Knowledge of the cardinal temperatures and germination rate may be useful as a criterion for determining planting dates and locations of a given species. These variables (temperature and rate) have been determined for a number of crops. However, this information is not available for husk tomato cultivars (Physalis philadelphica Lam.), even though this species ranks fourth in importance among the vegetables grown in Mexico. The aim of this study was to determine the cardinal temperatures and germination rates of seeds of Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo husk tomato cultivars. The presence of latency in these cultivars was discarded. This study was conducted in the Postgraduate College and the Autonomous University of Chapingo in 2011-2012. In germination chambers, seeds were germinated on filter paper in Petri dishes in darkness and constant temperature of 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40 and 45 °C, a completely randomized factorial experimental design with five replications per cultivar was used. The germinated seeds (emerged radicle) were counted and discarded every five days for 25 days. The cardinal temperatures for germination of Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo cultivars were: minimum: 7-9, 9, 7, 10 °C; optimum: 25-30, 30, 30, 25-30 °C respectively; maximum: 45 °C for all cultivars. The highest germination rates were: 23.4, 23.6, 21.8 and 18.7 seeds per day, respectively.

Keywords: Physalis philadelphica Lam; minimum; optimum and maximum temperature; latency

El conocimiento de las temperaturas cardinales y velocidad de germinación pueden ser útiles como criterio para la determinación de fechas y localidades de siembra de una especie dada. Dichas variables (temperatura y velocidad) se han determinado para cierto número de especies cultivadas. Sin embargo, no se encontró esta información para los cultivares de tomate de cáscara (Physalis philadelphica Lam.), no obstante que dicha especie ocupa el cuarto lugar en importancia entre las hortalizas cultivadas en México. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue determinar las temperaturas cardinales y las velocidades de germinación de las semillas de los cultivares Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla y Cerro Gordo de tomate de cáscara. Se descartó la presencia de latencia en estos cultivares. El presente estudio se realizó en el Colegio de Postgraduados y en la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo en 2011-2012. En cámaras de germinación se pusieron a germinar semillas sobre papel filtro en cajas Petri en oscuridad y temperatura constante de 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40 y 45 °C, el diseño experimental fue un completamente al azar con arreglo factorial con cinco repeticiones por cultivar. Se contaron y descartaron cada cinco días las semillas germinadas (radícula emergida) durante 25 días. Las temperaturas cardinales de germinación para los cultivares Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla y Cerro Gordo fueron: mínima: 7-9, 9, 7, 10 °C; óptima: 25-30, 30, 30, 25-30 °C respectivamente; máxima: 45 °C para todos los cultivares. Las mayores velocidades de germinación fueron: 23.4, 23.6, 21.8 y 18.7 semillas por día, respectivamente.

Palabras clave: Physalis philadelphica Lam.; temperatura mínima; óptima y máxima; latencia

The cardinal temperatures for germination refer to the maximum, minimum and optimum temperature and not necessarily to a single temperature but generally to a small temperature range in each case. Collectively the three temperatures are called cardinal temperatures for germination (Ginzo, 1980). Germination is expressed as percentage of germinated seeds in a sample. At temperatures below the minimum or above the maximum temperatures, the seed does not germinate and values between the maximum and minimum temperature, are called "temperatures for germination capacity" by Bewley and Black (1994). At extreme temperatures the lowest germination percentage is obtained (Besnier, 1989). On the other hand, between the maximum and minimum temperature occurs the optimum temperature, at which the maximum germination percentage is obtained in the shortest time (Hartmann and Kester, 1980; Besnier, 1989). Below and above the optimum temperature, the germination rate drops.

Bewley and Black (1994) emphasize that latency must be excluded when considering temperature effects on germination. Latency is defined as the inability of an intact and viable seed to germinate, even if it is under the required conditions for germination (Amen, 1968, Moreno 1984, Varela and Arana, 2011). Crop species usually have no latency, since man has discarded this feature through the domestication process, a feature that allows them to remain viable until environmental conditions are favorable for germination and seedlings establishment (Márquez et al., 2013).

Germination rate expresses the number of germinated seeds per day (Martínez et al., 2010). Maguire (1962) indicates that the germination rate is obtained as the germination percentages are determined.

Husk tomato is a vegetable of cultural and economic importance in Mexico (Santiaguillo and Blas, 2009). During 1990-1999 in the Central Region of Mexico, a 4.4% growth rate in harvested area and 6.5% in production volume was obtained (Garza, 2002). Husk tomato ranks fourth among the vegetables grown in Mexico (Santiaguillo et al., 2009) and is often planted in seedbeds or in polystyrene seedling trays and is then transplanted to a permanent site. The cardinal temperatures for germination have been determined mainly in crop species such as maize , rice, wheat, barley, rye, oats, tobacco (Mayer and Poljakoff - Mayber, 1975), chickpeas, lentils and soybeans (Covell et al., 1986) peanut and millet (Mohamed et al., 1988), and in some transplant vegetable crops as cabbage, cauliflower and tomato (Knott, 1962). However, there is no information available on this topic for husk tomato cultivars in the literature.

Knowledge of the cardinal temperatures and germination rate may be useful as a criterion in determining specific planting dates and locations, besides assuring enough seeds for planting to obtain an acceptable plant population, especially in transplant crops. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the cardinal temperatures and germination rate in Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo husk tomato cultivars.

The study was conducted in the Plant Physiology laboratory of the Botany Postgraduate Section, Campus Montecillo, Postgraduate College inAgricultural Sciences (Montecillo, Texcoco, State of Mexico) and the Seed Laboratory of the Department ofPlant Sciences at theAutonomous University of Chapingo (Chapingo, Texcoco, State of Mexico) during 2011-2012.

Seeds offour husk tomato cultivars (P philadelphica Lam.) were used: Diamante, Chapingo, Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo. Diamante is an early, high performance, large fruit size intervarietal hybrid, grown in the Bajío and Valles Altos. Chapingo, is an early, high performance cultivar, grown mainly in the Bajío and Valles Altos. Diamante and Chapingo, were generated in the Autonomous University of Chapingo (UACH) husk tomato breeding program, in the State of Mexico and the seeds were collected in 2007 (Peña , 2001).

Tecozautla is a population of collections made in the Tecozautla zone, Hidalgo in 2007, whose fruit is for export, with large size and long shelf life, grown mainly in the west side of the country in the states of Sinaloa and Sonora. Cerro Gordo, comes from the Cerro Gordo town in Salamanca, Guanajuato and the collection was made in 2006, is a high performance cultivar, with mid-size fruit, grown in the Bajío, Valles Altos and the northwest of the country (Pers. Com. Drs. Aureliano Peña Lomelí and Natanael Magaña Lira).

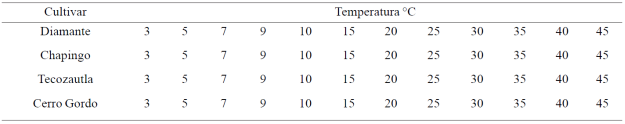

In order to determine the cardinal temperatures, data from the germination percentage and germination rate were obtained. For this, a completely randomized factorial design was used where the factors were cultivars and temperatures. The combination of the four cultivars and twelve temperatures resulted in forty-eight treatments (Table 1). For each treatment five replicates were used. The experimental unit consisted of a Petri dish with a hundred seeds. Groups of a hundred seeds per cultivar were placed on Whatman No. 43 filter paper disks within glass Petri dishes 9 cm in diameter. The Petri dishes containing seeds were placed in a germinator (Seedburo Equipment Inc.) of 242 dm3 capacity, except for temperatures 40 and 45 °C in which an oven (Thelco) with 90 dm3 capacity was used. Germination temperatures were constant according to treatment and in darkness. Irrigations with distilled water were performed if necessary.

Every five days, the Petri plates were checked, and germinated seeds were counted and removed, using biological germination as criterion, when the radicle protrudes (approximate size of 3-5 mm). This operation was performed for a period of 25 days or suspended sooner if one hundred percent of the seeds had germinated. From these data the total percentage and germination rate were obtained. Seeds used for germination tests at 40 and 45 °C were previously disinfected with a commercial solution of sodium hypochlorite at 5% (Cloralex®), because fungi were observed in preliminary tests only at these temperatures, thus at other temperatures, seeds required no disinfection.

For germination rate the formula proposed by Maguire (1962) was used, which expresses germination rate as the number of germinated seeds per day:

Where:

GR= germination rate (sum of the number of germinated seeds per day).

Number of germinated seeds (day count).

Days to first count and days to final count (from trial start).

Data were analyzed in a completely randomized design. Analysis of variance was carried out on the germination percentages, after arcsine transformation (Kuehl, 2001), within cultivars and within temperatures by the Statistical Analysis System software then Tukey means comparison tests, p ≤ 0.05 (SAS, 2002) were performed when significant differences were found. The same statistical analysis without data transformation were carried out for germination rate.

In the present study the presence of seed latency was discarded because they are commercially planted cultivars and have undergone a breeding process. Additionally, the viability test with 0.1% tetrazolium chloride was conducted and showing similar viability and germination percentages in the four cultivars (Table 2).

As for the cardinal temperatures, there were no differences between cultivars in the maximum temperature, but there were for the minimum and optimum. Minimum cardinal temperatures ranged between 7 and 10 °C since at 3 and 5 °C no cultivars germinated. The optimum germination temperature for Diamante and Cerro Gordo was 25-30 °C and 30 °C for Chapingo y Tecozautla (Table 3 and Figure 1). The highest germination percentages occurred in the range of 15-35 °C (Table 4).

Table 3 Cardinal temperatures and maximum germination percentage in husk tomato cultivars.

1El número entre paréntesis indica la temperatura (°C) a la cual se obtuvo el máximo porcentaje de germinación. Cabe mencionar, que no es la temperatura cardinal óptima debido a que no toma en cuenta la velocidad máxima de germinación.

Figure 1 Germination percentage of P. philadelphica Lam. in the range from 3 to 45 °C over a period of 25 days. A) cv. Diamante; B) cv. Chapingo; C) cv. Tecozautla; and D) cv. Cerro Gordo. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences (a= 0.05). Numbers inside the bars correspond to germination rates (number of germinated seeds per day)*. Circles indicate the minimum (green), optimum (red) and maximum (black) cardinal temperatures for germination.

Table 4 Germination percentages in four husk tomato cultivars at temperatures from 7 to 45 °C.

Medias con la misma letra dentro de columnas, son estadísticamente iguales (p≤ 0.05). El mayor porcentaje de germinación se alcanzó para Diamante y Chapingo a los 5 días, para Tecozautla a los 4.2 y Cerro Gordo a los 4.9 días.

The minimum cardinal temperatures of cultivars were 3-5 °C above the minimum for cabbage and cauliflower reported by Knott (1962). This author indicates 10 °C minimum and 35 °C maximum for tomato, lower than those of husk tomato. This illustrates the fact that the minimum and maximum cardinal temperatures are not interdependent.

Germination rate was the same among cultivars at temperatures of 7, 9 and 45 °C. From 10 to 40 °C differences were observed among cultivars. The rate in Diamante was higher than in Chapingo, Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo. At 30 and 35 °C the germination rate was equal for Diamante and Chapingo exceeding Tecozautla and Cerro Gordo. This shows the difference in cultivars response to temperature. According to data from this study, it is remarkable that the maximum germination percentage can occur at optimum temperature as indicated by the definition, for example in the Tecozautla cultivar. However, this percentage can move below or above the optimum temperature as in Diamante and Chapingo (Table 5 and Figure 1).

Table 5 Germination rate (number of germinated seeds day-1) in husk tomato cultivars at temperatures from 7 to 45 °C.

Medias con la misma letra dentro de columnas, son estadísticamente iguales (p≤ 0.05).

Conclusions

Differences were detected among cultivars in the minimum and optimum cardinal temperatures as well as in the maximum germination percentage. Differences in germination rate were found only in temperatures between 10 and 40 °C. Unlike Chapingo and Cerro Gordo, Diamante and Tecozautla cultivars are susceptible to be planted on an earlier date due to their lower minimum cardinal temperature for germination.

Literatura citada

Amen, R. D. 1968. A model of seed dormancy. Bot. Rev. 34:1-31 [ Links ]

Besnier, R. F. 1989. Semillas, biología y tecnología. Ediciones Mundi-Prensa. Madrid, España. 637 p. [ Links ]

Bewley, J. D. and Black, M. 1994. Seeds, physiology of development and germination. Ed. Plenum. 2nd edition. New York. U. S. A. 445 p. [ Links ]

Covell, S.; Ellis, R. H.; Roberts, E. H. and Summerfield, R. J. 1986. The influence of temperature on seed germination rate in grain legumes. J. Exp. Bot. 37(178):705-715. [ Links ]

Garza, L. J. Ma. 2002. Tomate verde: factores que determinan los niveles de productividad y rentabilidad en la Región Centro de México. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Centro de Investigaciones Económicas Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM). Reporte de Investigación 61. México. 54 p. [ Links ]

Ginzo, H. 1980. Fisiología vegetal. In: Sívori, E.; Montaldi, E. y Caso, O. (Ed). Fisiología de la germinación. Ed. Hemisferio Sur. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 681 p. [ Links ]

Hartmann, H. T. y Kester, D. E. 1980. Propagación de plantas. Principios y prácticas. Trad. al español de la edición en inglés por Ambrosio, A. M. Compañía Editorial Continental, S. A. México. 810 p. [ Links ]

Knott, J. E. 1962. Handbook for vegetable growers. Wiley, J. and Sons, Inc. New York. 245 p. [ Links ]

Kuehl, R. O. 2001. Diseño de experimentos. Principios estadísticos de diseño y análisis de investigación. Thomson Learning. 2a. (Ed.). México, D. F. 665 p. [ Links ]

Maguire, J. D. 1962. Speed of germination in selection and evaluation for seedling emergence and vigor. Crop Sci. 2 (2):176-177. [ Links ]

Márquez, G. J.; Collazo, O. M.; Martínez, G. M.; Orozco, S. A. y Vázquez, S. S. (Eds.). 2013. Biología de angiospermas. UNAM. Facultad de Ciencias. Coordinación de la Investigación Científica. 602 p. [ Links ]

Martínez, S. J.; Virgen, V. J.; Peña, O. M. y Santiago, R. A. 2010. Índice de velocidad de emergencia en líneas de maíz. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 1(3): 289-304. [ Links ]

Mayer, A. M. and Poljakoff-Mayber, A. 1975. The germination of seeds of plant physiology. Volume 5. 2nd (Ed.). Pergamon Press. Great Britain. 192 p. [ Links ]

Mohamed, H. A.; Clark, J.A. and Ong, C. K. 1988. Genotypic differences in the temperature responses of tropical crops. I.- Germination characteristics of groundnut (Arachis hypogeae L.) and Pearl millet (Penisetum typhoides S. & H.). J. Exp. Bot. 39(205):1121-1128. [ Links ]

Moreno, G. E. 1984. Análisis físico y biológico de las semillas agrícolas. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Autónoma de México (UNAM). México. 380 p. [ Links ]

Peña, L. A. 2001. Situación actual y perspectiva de la producción y mejoramiento genético de tomate de cáscara (Physalis ixocarpa Brot.) en México. In: Primer simposio Nacional. Técnicas modernas de producción de tomate, papa y otras Solanáceas. Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro (UAAAN). Saltillo, Coahuila. 10 p. [ Links ]

Santiaguillo, H. J. y Blas, S. 2009. Aprovechamiento tradicional de las especies de Physalis en México. Rev. Geog. Agríc. 43:81-86. [ Links ]

Santiaguillo, H. J.; Vargas, P. O.; Grimaldo, J. O.; Sánchez, M. J. y Magaña, L. N. 2009. Aprovechamiento tradicional y moderno de tomate (Physalis) en México. Publicaciones de la Red de Tomate de Cáscara. Folleto técnico Núm. 2. Septiembre 2009. México. 31 p. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System Institute (SAS). 2002. SAS/STAT user's guide. Versión 9.0. SAS. Institute. Cary, NC, USA. [ Links ]

Varela, A. S. y Arana, V. 2011. Latencia y germinación de semillas. Tratamientos pregerminativos. Serie Técnica: "sistemas forestales integrados". Sección silvicultura en vivero, cuadernillo Núm. 3. Área Forestal-INTAEEA. Bariloche, Argentina. 10 p. [ Links ]

Received: March 2014; Accepted: April 2014

texto en

texto en