Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Journal of behavior, health & social issues (México)

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0780

J. behav. health soc. ISSUES vol.5 no.2 Cuernavaca nov. 2013

https://doi.org/10.5460/jbhsi.v5.2.42304

Artículos de investigación general

Development of an academic self concept for adolescents (ASCA) scale

Construcción de una escala de autoconcepto académico para adolescentes (AAPA)

Gabriela Ordaz-Villegas*, Guadalupe Acle-Tomasini* y Lucina Isabel Reyes-Lagunes**

* Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Faculty of Higher Education (FES), Zaragoza.

** Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Psychology Faculty, Graduate Studies and Research Division.

Received: July 24, 2012.

Revised: June 17, 2013.

Accepted: August 18, 2013.

Abstract

Academic self-concept is the perception that a student has about his/her own academic abilities, constitutes one of the most relevant variables in the academic world, because of its influence on learning and cognitive functioning. Self-concept is a general assessment; nevertheless the current measurement instruments used for this construct are specific rather than general. Thus the purpose of this study was to construct and validate an academic self-concept scale with global dimensions, focused on teenager students. In its first stage, an open questions survey was designed to be applied with the intent of knowing the academic activities inside and outside the school. Afterwards, a closed questions survey was applied to a sampling consisting of 347 students ranging 14 to 18 years old from a public high school, east of México City. After obtaining the internal consistency and the items differentiation, a factorial analysis with orthogonal rotation was developed. The results grouped 16 items in 4 factors: self-regulation, general intellectual abilities, motivation and creativity. The scale shows 44.72% of a varying with a global Cronbach Alpha of .828. The present study contributes with an innovative scale with appropriate psychometric features, which globally assesses the academic self-concept.

Key words: Academic self-concept, self-regulation, motivation, creativity, school achievement.

Resumen

El autoconcepto académico es la percepción que un estudiante tiene sobre sus habilidades académicas, constituye una de las variables más relevantes dentro del escenario escolar, pues incide significativamente en el funcionamiento cognoscitivo y en el aprendizaje. El autoconcepto es una valoración global, no obstante, los instrumentos actuales que evalúan este constructo no cumplen con dicha característica, miden dimensiones específicas. De aquí que el propósito del presente estudio fue construir y validar una escala de autoconcepto académico con dimensiones globales para estudiantes adolescentes. En un primer momento se desarrolló un cuestionario de preguntas abiertas con la finalidad de conocer las actividades académicas dentro y fuera de la escuela. Posteriormente se elaboró un cuestionario cerrado. Éste último se aplicó a una muestra de 347 estudiantes de entre 14 y 18 años de edad, de un bachillerato público del oriente de la Ciudad de México. Después de obtener la consistencia interna y la discriminación de reactivos, se realizó un análisis factorial con rotación ortogonal. Los resultados agruparon 16 reactivos en 4 factores: autorregulación, aptitudes intelectuales generales, motivación y creatividad. La escala explica el 44.72% de la varianza, con un alpha de Cronbach global de .828. El presente trabajo aporta una escala renovadora con propiedades psicométricas adecuadas, que evalúa de forma global el autoconcepto académico.

Palabras clave: Autoconcepto académico, autorregulación, motivación, creatividad, logro académico.

Introduction

Academic self-concept is the perception and evaluation that a student has or does about his or her academic abilities (Marsh & Rhonda, 2002). This self-concept is one of the most important variables in the academic domain, due to its significant influence on appropriate cognitive functioning (Santana, Feliciano, & Jiménez, 2009). It directly affects learning processes (Vidals, 2005), academic achievement, and expectations of students (Henson & Heller, 2000). Additionally, it helps to create various cognitive and self-regulative strategies (Zimmerman, 2000), which reflect on academic performance (Campo-Arias et al, 2005; Schunk, Printrich, & Meece, 2008).

Academic self-concept is multidimensional (Shavelson, Hubner, & Staton, 1976). Many studies consider each academic subject area as a dimension, e.g., history, science, mathematics, spanish (Marsh, 1993; Shavelson et al., 1976). However, most research focuses only on spanish and mathematics, setting other taken subjects aside (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985; Plucker & Stocking, 2001). This causes some problems associated with evaluation and self-concept, especially when viewed in adolescents.

First, as individuals grow, the number of dimensions they can handle increases (Campo-Arias et al., 2005; González-Pineda, Núñez, & Valle, 2002; Marsh & Shavelson, 1985); therefore, if only two dimensions are used, evaluation is not thorough. Similarly, it is important to note that each dimension of academic self-concept has a different value and when dimensions are clustered together, a compensation effect among them is shown. Low self-concept in a subject area is compensated for by high self-concept in another one (González-Pineda, Núñez, González-Pumariega, & García, 1997; Marsh, 1993; Shavelson et al., 1976). In consequence, as self-concept is being studied in mathematics and spanish subject areas exclusively, then not only may collected data be biased but the possibilities of discovering potentially compensated dimensions, if any, for these two subject areas are lost.

Bandura (1987) states that self-concept is a global assessment. Nevertheless, currently a strong relation between self-concept in one dimension and its specific subject area can be seen, which indicates that evaluation depends on specific situations (Shavelson et al., 1976). It is clear that, on the one hand, the aim of obtaining a global assessment is not achieved and, on the other hand, the relation between self-concept and academic performance cannot be very close if both constructs are to be differentiated from one another (Palacios & Zabala, 2007).

In contrast, different dimensions comprising or clustered into academic self-concept are expected to bear a relation to one another (González-Pineda et al., 1997); however, several research studies show little or no correlation between mathematical and spanish self-concepts (Areepattamannil & Freeman, 2008). Marsh and Shavelson's (1985) conclusion is that verbal self-concept and mathematical self-concept are different and, therefore, cannot be added to an academic self-concept dimension.

By contrast, different empirical studies have found important divergence between students with high academic self-concept and students with low academic self-concept. Students with high academic self-concept value their own abilities, accept challenges, take risks, try new things (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003), and also create multiple cognitive strategies (González-Pineda et al., 1997). Moreover, they possess a higher motivation to complete difficult academic tasks and set higher goals (Pintrich, Roeser, & De Groot, 1994). In this sense, most students with high academic performance show high academic self-concept (Campo-Arias et al., 2005; Schunk, Printrich, & Meece, 2008).

Students showing low academic self-concept exhibit less confidence in their academic aptitudes (Amezcua & Fernández, 2000; Broc, 2000). They undervalue their talent, avoid situations that cause anxiety (Ommundsen, Haugen, & Lund, 2005); i. e., they have less cognitive and motivational resources than students with positive self-concept (Núñez et al., 1998). And this is reflected on low academic performance (Móller, & Pohlman, 2010). Accordingly, it is suggested that the abilities regulating learning and academic performance that can be considered are: both general and specific intellectual abilities, creativity, and motivation. In other words, learning is necessary to develop aptitudes, acquire knowledge, and create strategies, as well as intention and disposition (González, Valle, Suárez, & Fernández, 1999; López, Reyes-Lagunes, & Uribe, 2011; Risso, Peralbo, & Barca, 2010; Zacatelco & Acle 2009). Consequently, it is very important to take into account the perception and evaluation that an adolescent student has or does in relation to these abilities in order to measure his or her global academic self-concept.

Given the dilemma of the limitation of number of dimensions used to measure academic self-concept and its importance in explaining and predicting behavior in academic domain and expectations about the professional future of adolescent high school students, the aim of this study was to develop and validate psychometrically an instrument measuring academic self-concept through global academic dimensions, such as general intellectual abilities, specific intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity.

Method

Participants

The sample was non-probabilistic and consisted of 347 participants; 215 female (62%) and 132 male (38%) from grades 10 to 12 from a public secondary education school in Eastern Mexico City, with ages ranging from 14 to 18 years old (mean age = 16.17, SD = 1.084). School authorities determined group assignment.

Instrument

The purpose of the scale was to identify high or low levels of academic self-concept. Therefore, the instrument was developed based on a priori and emerging categories (Krippendorff, 2004). A priori categories were selected according to the literature (González et al., 1999; López et al., 2011; Risso et al., 2010; Zacatelco & Acle 2009) as follows: general intellectual abilities, specific intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity. Emerging categories were obtained from an early exploratory phase, through open questions focused on activities in which adolescents engage. Subsequently, the instrument was developed and the pilot test was administered to 10 expert judges in education. The test was administered individually. Each one of the recommendations made by the judges was considered. The scale consisted of 28 items with 5-point Likert-type responses, ranging from "Never", marked with number 1, to "Always", marked with number 5. Additionally, an identification sheet was included to collect personal and academic data, such as academic performance measured by school grades average, etc. (Appendix A).

Procedure

For the development of the instrument, first of all, previously established categories were used based on the literature as follows: general intellectual abilities, specific intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity. Subsequently, by means of some open questions in the exploratory phase, one of the a priori categories was ruled out and a new one emerged. Motivation was ruled out and perfectionism emerged; i. e., the pilot instrument categories changed to the following: general intellectual abilities, specific intellectual abilities, creativity, and perfectionism.

Based on the above-mentioned, an instrument was developed, and validated by 10 expert judges. All the judges are professors in different Schools of Psychology of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (National Autonomous University of Mexico), with a PhD in an area of education. In order to get the instrument to measure adequately and clearly the construct, each judge was asked individually to validate the content of each item. They were requested to cross the items that were inadequate for measuring academic self-concept, and also to provide input on writing clarity. A blank for comments and suggestions was included in each item. All of the 28 items put to validation were approved, some with observations that were taken into account until every one of them was covered.

Before administration to adolescents, an informed consent form was requested to school authorities, and teachers, as well as group participants. A brief explanation on the purpose and importance of completing the scale was provided and they were asked to agree. Group administration was used.

Upon administration, the following were carried out: 1) a frequency, skewness, and kurtosis analysis; 2) a differentiation analysis through a Student's t-test, with a significance level of 0.5 to choose items to be kept in the procedure; 3) a factorial analysis of principal components with orthogonal rotation to measure construct validity; and lastly 4) a Cronbach's alpha and factor analysis to measure consistency.

Results

Scale item distribution showed tendency towards normality, with a mean of 96.55 and a standard deviation of 15.191 (Figure 1).

In order to measure the power of item differentiation, frequency distribution was analyzed (skewness and kurtosis). Each item was submitted to a Student's t-test, and directionality was obtained through cross tabulation. Based on the results from these tests, 8 items were decided to be ruled out. Based on the intercorrelation analysis using the Pearson's formula, a factorial analysis of principal components with orthogonal rotation was carried out, since correlations were moderate. With the purpose of knowing the dimensions comprising academic self-concept construct, items with factor loadings of .48 or higher were selected.

Based on criteria, 16 items were clustered into four factors representing the 44.72% of total variance, with a global Cronbach's Alpha of .828. Alphas by factors were as follows: factor 1 = .683; factor 2 = .621; factor 3 = .651; and factor 4 = .684. Factor weights and distribution of items into four factors are shown in Table 1.

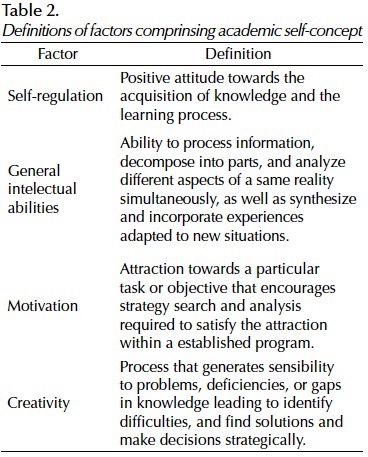

Based on item distribution, academic self-concept construct refers to self-perception and evaluation of a student on his or her self-regulation, general intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity, as defined in Table 2.

Explained variance and cumulative variance, as well as mean and standard deviation, by factors are shown in Table 3. As can be seen, self-regulation is the dimension showing a higher explained variance in academic self-concept.

Upon obtaining the factors, a correlation analysis was conducted through a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient in order to know the relation between factors comprising the academic self-concept scale. Results are shown in Table 4.

As can be seen, positive correlations occur between all factors as expected, which indicates that factors originate from the same construct. Finally, in order to know the difference in academic performance between students showing high and low academic self-concept, a Student's t-test was conducted for independent samples. Academic performance (t = -4.602, p = 0.000, 95% CI [-.077, -0.31]) of students with low academic self-concept (mean low ASC = 8.43; SD = .81) was found to differ significantly compared to that performance measurement of students with high of students with high academic self-concept academic self-concept being higher. (mean high ASC = 8.98; SD = .68), the academic performance measurement of students with high academic self-concept being higher.

Discussion

The factorial structure of the Academic Self-Concept Scale was organized by four dimensions as follows: self-regulation, general intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity. It was interesting to observe that self-regulation emerged as a new factor that was not considered when the scale was being initially developed. This factor is of the utmost importance since, on the one hand, it had the highest weight in the scale; and on the other hand, self-regulated students create learning, planning, monitoring, and evaluation strategies, as well as organization and restructuration of their learning environment, i. e., students play an active role in their own learning process, which results in high academic performance that in turn reflects on a high academic self-concept (Zimmerman, 2000).

In contrast, construct multidimensional nature is still observed across the diversity of factors obtained in the Academic Self-Concept Scale as described in many studies (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985; Shavelson et al., 1976). Said dimensions showed a moderate and necessary relation to be considered as part of the same construct (González-Pineda et al., 1997), whereas a relative independence occurred, allowing factors to distinguish from one another (Palacios & Zabala, 2007).

Likewise, the use of a global dimension met the objective of inclusive integration of facets determining academic self-concept, thus over-coming the dilemma of missing dimensions that adolescent students can handle (Campo-Arias et al., 2005; González-Pineda, et al., 2002; Marsh & Shavelson, 1985). Also the problem involving the close relation between a specific dimension and its corresponding subject (Marsh & Parker, 1984) is settled since data on a particular school subject is not required, but data on ability perception that enhance learning and high academic performance, as reflected on the dimensions and items that comprise the scale.

Lastly, academic performance differences between students with high academic self-concept and students with low academic self-concept were detected, which is in agreement with previous findings showing that most students with high academic performance exhibit high academic self-concept, and in contrast, students with low academic performance show low academic self-concept (Campo-Arias et al., 2005; Henson & Heller, 2000; Schunk et al., 2008).

Therefore, in conclusion, this study provides a culturally relevant, innovative scale with appropriate psychometric properties, which allows us to differentiate between adolescent students with high academic self-concept levels from those with low academic self-concept levels. Having instruments that allow us to assess academic self-concept more thoroughly is of the utmost importance since this construct regulates cognitive/motivational strategies involved in learning and academic performance (Henson & Heller, 2000; Zimmerman, 2000), and affects professional expectations of students (Santana et al., 2009). So identifying self-concept is crucial for unleashing students' potential in a critical stage for their cognitive, social and emotional development.

References

Amezcua, J., & Fernández, E. (2000). La influencia del autoconcepto en el rendimiento académico. Iberpsicología, 5(1). Recuperado de: http://www.fedap.es/IberPsicologia/iberpsi5-1/amezcua/amezcua.htm. [ Links ]

Areepattamannil, S., & Freeman, J. (2008). Academic Achievement, Academic Self-Concept, and Academic Motivation of Immigrant Adolescents in the Greater Toronto Area Secondary Schools. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19, 700-743, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-831. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. (1987). Pensamiento y acción. Barcelona. Martínez Roca. [ Links ]

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: how different are they really?. Educational Psychology, 15(1), 1-40, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382. [ Links ]

Broc, M. (2000). Autoconcepto, autoestima y rendimiento académico en alumnos de 4° de la E.S.O. Implicaciones psicopedagógicas en la orientación y tutoría. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 18(1), 119-146. [ Links ]

Campo-Arias, A., González, S., Sánchez, Z., Rodríguez, D., Dallos, C., & Díaz-Martínez, L. (2005). Percepción de rendimiento académico y síntomas depresivos en estudiantes de media vocacional de Bucaramanga, Colombia. Archivos de Pediatría del Uruguay, 76(1), 21-26. [ Links ]

González, R., Valle, A., Suárez, J. M., & Fernández, A. (1999). Un modelo integrador explicativo de las relaciones entre metas académicas, estrategias de aprendizaje y rendimiento académico. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 17(1), 47-70. [ Links ]

González-Pineda, J., Núñez, J., González-Pumariega, S., & García, M. (1997). Autoconcepto, autoestima y aprendizaje escolar. Psicothema, 9(2), 271-289. [ Links ]

González-Pineda, J., Núñez, J., & Valle, A. (2002). Influencia de los procesos de comparación interna/externa sobre la formación del autoconcepto y su relación con el rendimiento académico. Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada. 45, 73-82. [ Links ]

Henson, K., & Heller, B. (2000). Psicología educativa en la enseñanza eficaz. México: Internacional Thompson Editores México. [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An introduction to its methodology. USA: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

López, A., Reyes-Lagunes, I., & Uribe, J. (2011). Construcción y validación psicométrica de una escala de intención de meta. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica, 31(1), 133-156. [ Links ]

Marsh, H. (1993). The multidimensional structure of academic self-concept: invariance over gender and age. American Educational Research Journal, 30(4), 841-860, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00028312030004841. [ Links ]

Marsh, H., & Parker, J. (1984). Determinants of student self-concept: Is it better to be a relatively large fish in a small pond even if you don't learn to swim as well?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 213-231, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.1.213. [ Links ]

Marsh, H., & Rhonda G. (2002). The pivotal role of frames of reference in academic self-concept formation: The "big fish-little pond" effect. In Pajares, F. & Urdan, T. (coord.). Academic motivation of adolescents. Inglaterra: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Marsh, H., & Shavelson, R. (1985). Self-Concept: Its Multifaceted, Hierarchical Structure. Educational Psychologist, 20(3), 107-123, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2003_1. [ Links ]

Möller, J., & Pohlmann, B. (2010). Achievement differences and self-concept differences: Stronger associations for above or below average students?. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 435-450, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709909X485234. [ Links ]

Núñez, J., González-Pineda, J., García, M., González-Pumariega, S., Roces, C., Álvarez, L., & González, M. C. (1998). Estrategias de aprendizaje, autoconcepto y rendimiento académico. Psicothema, 10(1), 97-109. [ Links ]

Ommundsen, Y., Haugen, R., & Lund, T. (2005). Academic Self-concept, Implicit Theories of Ability, and Self-regulation Strategies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(5), 461-474, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00313830500267838. [ Links ]

Palacios, E.G., & Zabala, A.F. (2007). Los dominios social y personal del autoconcepto. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 12, 179-194. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P., Roeser, R., & De Groot, E. (1994). Classroom and individual differences in early adolescents' motivation and self-regulated learning. Journal of Early Adolescence, 14(2), 139-161, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/027243169401400204. [ Links ]

Plucker, J., & Stocking, V. (2001). Looking outside and inside: Self-concept development of gifted adolescents. Exceptional Children, 67, 535-546. [ Links ]

Risso, A., Peralbo, M., & Barca, A. (2010). Cambios en las variables predictoras del rendimiento escolar en enseñanza secundaria. Psicothema, 22(4), 790-796. [ Links ]

Santana, L., Feliciano, L., & Jiménez, A. (2009). La influencia del autoconcepto en el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. REOP, 20(1), 16-28. [ Links ]

Schunk, D., Pintrich, P., & Meece, J. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory,research, and application. New Jersey, EU: Pearson. [ Links ]

Shavelson, R., Hubner, J., & Stanton, G. (1976). Validation of construct interpretations. Review of educational Research, 46, 407-441, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407. [ Links ]

Vidals, A. (2005). Autoconcepto, locus de control y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de segundo semestre de la facultad de psicología (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. [ Links ]

Zacatelco, F., & Acle, G. (2009). Modelo de identificación de la capacidad sobresaliente. Revista Mexicana de Investigación en Psicología. 1 (1), 41-43. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, B. (2000). Self-efficacy: an essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 82-91, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016. [ Links ]

Notes

Authors contributed to the paper in the following way; GOB: literature review, article development and statistical analysis, GAT:direction and literature review and LIRL: statistical analysis orientation.

Self-references for authors: 2.

Self-references for the JBHSI: 0.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gabriela Ordaz-Villegas, PhD.

FES, Zaragoza campus 1,

Av. Guelatao No. 66 Col. Ejército de Oriente,

Iztapalapa, C.P. 09230, México D.F.

E-mail: gabordaz@yahoo.com.mx, ordaz.villegas@comunidad.unam.mx.

About the authors:

Name: Gabriela Ordaz Villegas. Degree: PhD in Educational and Developmental Psychology. Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Affiliation: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Faculty of Higher Education (FES), Zaragoza, asignature professor, Psychology. Line of research: Factors associated with outstanding skills, intelligence, creativity, academic self-concept and academic performance. Address: FES, Zaragoza campus 1, Av. Guelatao No. 66 Col. Ejército de Oriente, Iztapalapa, C.P. 09230, México D.F. E-mail: gabordaz@yahoo.com.mx, ordaz.villegas@comunidad.unam.mx.

Name: Guadalupe Acle Tomasini. Degree: PhD in Social Anthropology, Iberoamerican University. Affiliation: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Faculty of Higher Education (FES), Zaragoza, tenure professor C, graduate division. Line of research: Resilience and factors associated with school integration of children with disabilities or outstanding abilities. Social validation of the ecological model of risk / resilience in special education. Distinctions: Prize of the Psychology Mexican Society 2013 in the category of Teaching. Address: FES, Zaragoza campus 2, Batalla 5 de mayo s/n esq. Fuerte de Loreto, Col. Ejército de Oriente, Del. Iztapalapa, C.P. 01010. Tel. 55+56230708 ext. 102. E-mail: gaclet@unam.mx.

Name: Lucina Isabel Reyes Lagunes. Degree: PhD in Social Psychology, Psychology College. Philosophy and Letters Faculty, (1966-1968). Post-doctoral stay: The University of Texas, at Austin, U.S. (1969-1970). Affiliation: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Psychology Faculty, Graduate Studies and Research Division. Emeritus professor. Line of research: Personality, culture, political psychology and ethno psychometric: cultural approach to psychological measurement. Other Positions: Member of the National Researcher's System (S.N.I.) level III. Member of the Graduate Studies Academic Committees: Medical sciences, odontological and health, and psychology. Technical Advisor in the Department of Social and Environmental Psychology. Address: UNAM, CU, Av. Universidad 3004, CU. Copilco. 04510. Coyoacán. México D. F. Tel: 56 22 23 23. E-mail: lisabel@unam.mx.