Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Journal of behavior, health & social issues (México)

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0780

J. behav. health soc. ISSUES vol.5 no.2 Cuernavaca Nov. 2013

https://doi.org/10.5460/jbhsi.v5.2.42252

Artículos de número monográfico

Social representation of conditions for happiness and living experiences source of happiness in Chile and Italy

Representación social de condiciones y experiencias vitales fuente de felicidad en Chile e Italia

María José Rodríguez-Araneda

Universidad de Santiago de Chile, School of Psychology, Santiago, Chile.

Received: November 21, 2012.

Revised: May 15, 2013.

Accepted: July 23, 1013.

Abstract

The research is aimed at understanding and qualitatively describing the social representation of conditions for happiness and of living experiences source of happiness in the discourse of socializing agents in matters of well-being and quality of life. Whether these attributions are consistent with the findings of positive psychology was also analyzed. The study was non experimental, transversal, cross-cultural, and qualitative. The sample was non-probabilistic and included health and education students and professionals in Chile and Italy. Open-ended questions were applied to students of psychology, obstetrics and related fields of both sexes aged between 18 and 38 years. Focus groups were conducted with students and professionals of both sexes, including educators, psychologists and related professionals, aged between 22 and 67 years. People attributed happiness to external conditions (affection and personal freedom) and internal factors (psychological capital). The discourse balanced the presence of experiences of satisfaction by reception (passive role) and by realization (active role). The ranges of these experiences vary from individual to collective scopes. A common nucleus of social representation in both groups was identified, which included elements that positive psychology has linked with happiness. This information guides the training of professionals influencing the lifestyles of the population.

Keywords: Social representations, happiness, conditions and living experiences source of happiness, psychological capital, cross-cultural study.

Resumen

La investigación tuvo como objetivo comprender y describir cualitativamente la representación social de las condiciones y experiencias vitales fuente de la felicidad en los discursos de agentes socializadores en materia de bienestar y calidad de vida. Se analizó además si estas atribuciones se condicen con los hallazgos aportados desde la psicología positiva. El estudio fue no experimental, transeccional, transcultural y cualitativo con muestras no probabilísticas de estudiantes y profesionales de la salud y la educación en Chile e Italia. Se aplicaron cuestionarios de preguntas abiertas a estudiantes de ambos sexos de carreras de psicología, obstetricia y afines de entre 18 y 38 años de edad. Se realizaron grupos focales con estudiantes y profesionales de ambos sexos, incluyendo educadores, psicólogos y profesionales afines, con edades entre los 22 y 67 años. Las personas atribuyeron la felicidad a condiciones externas (afectos y la libertad personal) e internas (capital psicológico). Entre las fuentes de la felicidad el discurso equilibró experiencias de satisfacción por suscepción (rol pasivo), como por realización (rol activo). Los alcances de dichas experiencias variaron de lo individual a lo colectivo. Se identificó un núcleo común de la representación social para ambos colectivos, que incluyó elementos que la psicología positiva ha relacionado a la felicidad. Esta información orienta la formación de los profesionales que ejercen influencia en los estilos de vida de la población.

Palabras Clave: Representaciones sociales, felicidad, condiciones y experiencias vitales fuentes de felicidad, capital psicológico, estudio transcultural.

Introduction

Positive psychology is a recent field of research that is centered on the meaning of the happy moments of human life (Seligman, 2003). The studies have contributed novel information with respect to what makes people happy (Lyubomirsky, 2008). However, research on these issues is just starting in Latin America (Reyes-Jarquín & Hernández-Pozo, 2012) and the socialization of this knowledge is recent.

Now, in the daily life setting, together with expert discourse, there is the construction of common sense knowledge, a space in which social representations (SRs) are constructed. Although they are nourished from formal knowledge, they evolve in a manner that belongs to social conversation, they are naturalized and acquire the status of fiduciary reality in everyday life (Moscovici, 1993). So a SR is finally a point of reference of social practice, knowledge, and action systems. It also expresses social subjectivity and is objectified in multiple codes, standards, values, monuments and organizations (González, 2008).

The objective of this research is to understand and describe qualitatively the meanings associated with the social representation of the causal attributions of happiness that are reproduced in everyday life. Which are the conditions that are deemed necessary for happiness? Which are the vital experiences that are considered sources of happiness? Is it believed that happiness is an event that takes place passively or is it the result of an active behavior?

With the purpose of gaining access to core aspects of SR, the study was made transculturally. Participants from Chile (Santiago) and Italy (Rome), both of them latin, western and modern countries, were included. They have important economic differences, but similar levels of human development: 0.783 Chile and 0.854 Italy (United Nations Development Programme, 2011) and happiness: 6.5 Chile and 6.9 Italy (New Economics Foundation, 2009), 6.82 Chile and 6.77 Italy (Veenhoven, 2011).

In the literature no record was found on studies of the SR of happiness. The study of Sotgio, Galati & Manzano (2011) compared the subjective representation by elderly adults in Cuba and Italy of the components of happiness (what people consider that is needed to be happy). The study identified that Italians give greater value to health, family and money, while the Cubans valued health, love and faith. Only the Italians mentioned hobbies, sex and good luck, and solely the Cubans referred to safety and dealing with adversity.

In view of the complexity of the processes of construction of social reality, the present research was centered on understanding the SR of students and professionals in the areas of education and health, whose influence scenarios as transmissions of meanings encompass schools, training centers in general, consultation rooms in health centers, as well as spaces for education and research in quality of life. In those spaces the discourses achieve the status of expert, and therefore exert a particular influence on the reproduction of meanings and the socialization of associated practices, turning these professionals into socializing agents in quality of life.

The results will allow us to observe whether these attributions agree with what is contributed by the empirical evidence coming from positive psychology, with the purpose of being able to provide feedback to the socialization spaces. It is also foreseen that the results will facilitate the understanding of social discourses and behaviors in relation to the search for well-being. This information can contribute to the construction of complementary training programs for socializing agents that are strategic at the time of improving the happiness level of people. Therefore, the research is added to the effort for contributing knowledge that will facilitate the orientation of public policies (Diener, Kesebir & Lucas, 2008; Reyes-Jarquín & Hernández-Pozo, 2012).

Findings in Relation to the General Causes of Happiness

In positive psychology two conceptual aspects have been identified. The eudaimonic perspective identifies happiness with the full development of persons and virtue (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff & Singer, 2008). From that standpoint the multidimensional model of psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989) defines it as a state of well-being composed of self-acceptance, positive relations with other persons, autonomy, mastery of the surroundings, purpose in life, and personal growth. On the other hand, the hedonic perspective identifies happiness with the subjective experience of pleasure versus displeasure. The latter perspective also calls it subjective welfare and describes it as composed of pleasant emotional aspects and positive cognitions (Diener, 1984; Diener, Suh, Lucas & Smith, 1999).

Veenhoven has done research along the line of happiness as subjective well-being (1993; 2005). He finds that the livability factors of society (environmental conditions) that are correlated with happiness have to do with 77% of the differences in national happiness. Material abundance in the poor countries, safety, freedom, gender and class equality, cultural and social climate, modernization, social position of the individual, and low levels of adversity stand out among them. Positive relations with livability occur in the individual (person's conditions). Such is the case for mental and psychological health (resilience), social skills (assertiveness and empathy), and personality traits (extroversion and internal control locus).

Lyubomirsky, Sheldon & Schkade (2005) estimate that only 10% of the differences between the levels of individual happiness are determined by the circumstances of life, 50% by genetic factors, and 40% by the deliberate action of the person. Among these voluntary activities, those that increase the levels of happiness are mainly to express gratitude, cultivate optimism, avoid overthinking and social comparison, practice kindness, show concern for relations, develop strategies for coping, learn to forgive, practice activities that generate flow or compenetration (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), savor the joys of life, show commitment with one's own objectives, practice religion and spirituality, and care for the body, for example through good eating habits and physical activity (Lyubomirsky, 2008).

On the other hand, Seligman points out that in addition to savoring and paying conscious attention to sensual pleasures, the need to identify and cultivate character strengths is crucial (2003), so as to then practice activities that generate gratification and imply an increase of the person's psychological capital. He also recommends to develop a high level of satisfactory socialization and to cultivate optimism (Seligman, 1998; 2003). Another aspect consists in combining a) a pleasing life (centered on experiencing positive emotions), b) a committed life (use of the strengths to obtain gratifications) and c) a significant life (use of the strengths and virtues in the service of something that transcends the persons themselves), which would constitute the three itineraries toward happiness (Duckworth, Steen & Seligman, 2005; Seligman; 2003).

It can be seen that hedonic happiness is unsustainable in the long term in the absence of eudaimonic well-being. Since both are strongly correlated, some authors have questioned the usefulness of distinguishing them in empirical jobs (Fisher, 2010).

The Social Representations

Beyond the expert discourses, it is in the social group's daily exchange that common sense knowledge is generated, making physical and social reality intelligible. Based on socially constructed and shared cognitive schemes, individuals construct their own individual mental representations, putting in action their symbolic and cognitive activities (Jodelet, 1984). In this way SRs are constructed that operate as organized knowledge systems, with their own logic and language, which do not represent simple opinions but the actual reality of a phenomenon (Salazar & Herrera, 2007).

These ingenuous theories allow, through communication, the members of a society to understand, create and recreate a dynamic reality to which they attempt to attribute some regularities (Moscovici, 1993). Thus, a SR helps people privilege, select and retain some important facts from the ideological discourse concerning the relations that they establish when they interact with their surroundings.

SRs have a characteristic architecture (Abric, 1984). The central core is the most stable, coherent and rigid part of the representation, anchored in the collective memory. It provides historical and social continuity. Peripheral elements agglutinate around it. They are composed of opinions, beliefs, attributes and information which are more sensitive to the social context and lead to the adaptation of groups of individuals to specific situations.

Finally, a SR is translated into the construction of an explicative and evaluative mini-model of the surroundings that impregnates the subject. This process reconstructs and reproduces reality, furnishing sense and procuring an operational guide for social life (Páez, 1987), providing scripts of behavior, attitudes and ideologies (Salazar & Herrera, 2007; Van Dijk, 2000). The above therefore implies that these meanings affect deeply the conduct of individuals, their decision making, and the interpretation of their experiences. It is in this sense that it is important to understand the SRs of the conditions and the vital experiences source of happiness in persons that socialize through their social roles, beliefs on happiness and its causes.

Method

Participants

This study involved the participation of 230 university students and professionals from the areas of health and education in Chile (Santiago) and Italy (Rome), belonging to the careers of Psychology, Obstetrics and Puericulture, and Education. Table 1 shows by country those who answered questionnaires and participated in the focal groups of students or professionals.

Materials

Two techniques for collecting information were combined: 1) open ended question surveys and 2) focus groups. For the questionnaire phase the Social Representation of Happiness Questionnaire was constructed and applied, with two open-ended questions in the Chilean version: "To me happiness is...?" and "A happy person is one that...?"; to which a third question was added later in the Italian version: "To you, which are the sources of happiness...? (please consider your role, that of others, and that of the environment)." The participants' age, career and sex were also recorded. The aim was to study SRs through nondirective instances that would allow the development of a narrative beyond the conscious and direct responses, to avoid falling into a study of individual opinions (González, 2008). To that end, in the focus group phase eight nondirective group interviews, four in each country, were made.

Procedure

The methodological design was non-experimental and transectional, using a qualitative methodology with a transcultural scope. Information was gathered in Chile in 2008 and then in Italy in 2009.

For the questionnaire phase the participants were contacted using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling (based on availability) accessed voluntarily. The number was estimated according to the capacity for collecting and analysis. The questionnaires were answered in classrooms with the approval of the professors in charge and after explaining to the youngsters the meaning of the research. Informed consent and the use of anonymity were applied.

In the case of the focus groups the contact was made by the snowball technique. The focus groups were formed with voluntary participants who were called to classrooms (students) or meeting rooms (professionals). The sense of the research was explained and informed consent was applied. The participants were identified by their given names. The focus groups were transcribed completely. In the case of the Italian sample they were translated into Spanish.

The analysis of the information was made as a function of the emergent contents from the open coding, then axial, and finally selective stages, until a comprehensive scheme of the results was developed (process based on grounded theory). The above was complemented with the procedure of generation of socio-semantic categories and dimensions based on the ideas of discovery in progress, coding, refining, and relativization of the findings according to the contexts (Taylor & Bogdan, 1987).

Among the validation criteria that legitimate the research, those of credibility, transferability and coherence were fulfilled. As a criterion of rigor, use was made of the triangulation of participants, their voice and multivocality, and the reflexivity of the investigator (Sisto, 2008).

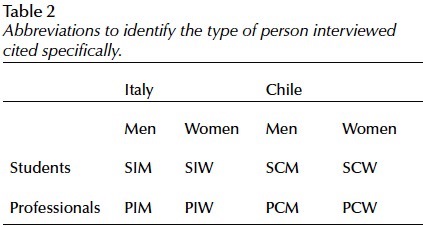

The textual citations are presented in the results with the abbreviations given in Table 2.

Results

The results are qualitative descriptions that were organized as a function of two dimensions: 1) conditions for happiness: external (environmental characteristics) and internal (person's characteristics); and 2) types of experiences source of happiness: experiences of satisfaction by susception and experiences of satisfaction by realization. Although the objective of the research was to understand and describe qualitatively meanings associated with core contents of the SR of the causal attributions of happiness, for some of which there were qualitative differences by country, which are indicated explicitly for each dimension.1

The Social Representation of the Conditions for Happiness

The participants expressed that some external and internal conditions are necessary on which it is possible to start having and constructing happy vital experiences (see Table 3). For some people these conditions are desirable, for others they are indispensable.

The external conditions were identified with the need for a setting that provides satisfiers that are valued individually. The satisfiers considered basic were referred to the satisfaction of physiological needs. The satisfiers that were reported by the participants as the most valuable for achieving happiness were affection and personal freedom; other conditions like safety and social consideration were also mentioned. Some discourses sustained that happiness requires a perfect environment.

The responses on internal conditions referred to two types: 1) biological characteristics like physical health and temperament, and 2) psychological capital for a) assertion of the self; b) construction of positive relations with others; c) stressing what is positive in life.

External Conditions

In general, the responses are dichotomized between the need for a benign versus a perfect context.

Benign environment: In the discourse the importance attributed to the occurrence of positive events was common: enjoying public safety and economic stability, having free time, not having many difficulties, well-being of loved people, and social consideration."... has monetary and job stability that agrees with his life style" (SCM).

Perfect environment: It was verbalized that to be happy it is necessary to have an environment that provides all the satisfiers valued by the subject. This narrative appeared only in some students from both countries and not in the professionals. "...happiness does not depend on me, it is the events that determine it completely" (SIW); "... nothing bad is happening, i.e., things that are good and favorable are taking place" (SCW).

The importance attributed to the environmental conditions was a common response among Italian students, but not so among Chilean students and professionals.

On the other hand, valued conditions were affection and personal freedom.

Affection: as a valued condition, the people pointed out the need for a context that provides affection, personal value feedback and support. "...having many persons around you who love you a lot" (SCW); "... the lack or scarcity of deep human relations is the cause of no happiness" (SIW); "... having people who support you. You feel loved... having good relations with the people you love" (SCM). This representation, mainly at the level of feeling loved, was slightly tinted with youth. It is an environmental factor considered basic and irreplaceable.

Personal freedom: A non-coercive context that allows autonomy and development. "... free to be able to choose, project, create..." (SCW); "be free to make one's own decisions" (SIW). It also refers to having free time and opportunities for action.

Summarizing, the centrality of affection and personal freedom was seen in almost all the discourses, the same as the need for a benign context that can reach the significant persons, more than perfect or exclusively individual.

Finally, some persons situated the locus of control for generating these conditions fully in what is external: a provider context. However, what was common in the discourse was the recognition of the need to exert an active role that allows the person to construct positive circumstances. "...it also depends on external factors that have an influence on our happiness... basically what comes first is our role and then that of others" (SIW). It is here that the conditions of the environment interact with the characteristics of the subject himself. The above introduces us into the second block of results.

Internal Conditions

Two types of qualities that a person must have to be happy were seen: those related to the persons' characteristics of a biological kind and those that refer to their psychological capital.

Characteristics of a biological type: In this group physical health as well as temperament characteristics were mentioned. For physical health: "... has good health and physical welfare" (SCM). For temperament: "...quiet, relaxed, serene" (SIM); "...is a cheerful person" (SIW). The Italian sample emphasized serenity and cheerfulness as stable qualities of the personality trait kind. The Chilean sample did not refer to stable traits, and when cheerfulness was mentioned, it was done as an emotion associated with happiness.

Psychological capital: Emphasis on the person's psychological capacity for happiness was preponderant. This psychological capital implies a number of psychic resources activated from one's own human agency. It allows the individual to cope in everyday life in a functional and satisfactory manner. The SR of the psychological capital was grouped in three types of abilities: a) to assert oneself; b) to construct positive relations with others; and c) to stress the positive aspects of life (see Table 4).

1) Abilities to assert oneself: ability to take charge of one's own well-being, prevalence of the internal control locus, and ability to act in an empowered mode and in evaluative coherence. The responses referred to emotions, cognitions and conducts of positive self-assessment, exercising personal power, and effective coping.

The positive self-assessment responses included self-knowledge, self-esteem, self-care and self-confidence. "...confidence in oneself" (SIW); "... one is self-knowledge...knowing who one is, of caring for oneself in that knowledge" (PCW); "... is capable of finding oneself, one's personality, one's real self, and once found, loving it and accepting it for what it is" (SCW).

Responses that emphasized the exercise of personal power, autonomy and leadership in the project of life were intense among the students. "...is not afraid of hearsay... can assert his rights" (SCW); "...fulfills his dreams even lacking the tools to fulfill them, because he always sets goals to be overcome and he would give his life in these attempts" (SCM); "Happiness goes through... the personal decision of being happy, transcending what happens ...understanding that not everything can be controlled. It is like taking the ship's helm" (PIW).

The effective coping responses included active confrontation of the difficulties as well resilience and ability to overcome frustrations, losses, failures and grief, resignifying the events in a constructive manner. They implied the ability to tolerate frustration, to be creative in the search for new alternatives, in addition to learn and grow through adversity. "... bears in mind that the problems can be overcome. This does not mean that she does not feel anguish or sorrow, but that she knows how to overcome them and not remain entrapped in them" (SCW); "...suffering is not in vain, it is an opportunity for growth." (PIM). The ability to accept frustrating as well as satisfying experiences as a natural part of life was also highlighted "... enjoys the possibility of be and live the sorrows and joys as part of being happy and part of living" (SCW). The discourse on confrontation and resilience played a principal role among participants in Chile, both students and professionals.

2) Ability to build positive relations with others: the importance of social skills such as sociability, authenticity and expressiveness was stressed. "...expressive, nice, smiling" (SIW); "... have the freedom to express oneself" (SCW).

Also the need to develop emotions, cognitions and conducts of consideration toward others, such as empathy, altruism, faith in others, kindness and solidarity. "... motivated to empathy, courteous, obliging" (SIM); "... is capable of establishing horizontality, respect, and collective construction relations ..." (SCW); "... trusts others" (SIW); "...cultivates respect... does not harm others nor the surroundings and is motivated by an ethics based on freedom and on what is social, never on what is individual" (SCM). Participants in Chile pointed out the ability to forgive and apologize. "...to be capable of apologizing and also of forgiving" (SCW).

In the SR this is coherent with the importance of establishing relations with other living beings, not only people, and to have positive social and affective experiences.

3) Ability to highlight what is positive in life: set of qualities to allow to relate constructively and positively with life and its changes. Various cognitive, emotional and behavioral strategies that highlight positive over negative aspects.

The ability to highlight the positive was pointed out: valuation of things present and past, know how to appreciate what has happened, feel gratefulness, pay attention to the positive. "... is grateful" (SCM); "...develop a good, positive, balanced, constructive point of view on things" (PIW); "... see the glass half full" (SIM).

Also the ability to live and enjoy the present, get involved with what is current, be in what is synchronic, and highlight satisfaction experiences that occur in everyday life. "... enjoys the now" (SCW). This implies accepting the flow of experiences, being able to act in them in a conscious way and enjoy what is positive together with the contrasts of everyday life. "...what matters is to feel... some emotion, because when you are not open you do not feel, you do not live in reality... knowing...living all the emotions. Happiness, sadness, anger, fear" (PIM).

Another element was the ability to have a positive projection of the future, being optimistic or having faith. "... live every moment of life with a perpetual yes!, everything will be all right ..." (SCW); "...he is an optimistic person" (SIM).

Development of a positive disposition toward life was distinguished, and this was identified as wanting to live, love for life, and having a purpose. "... it is like a state of happiness in which there is no reason not to be happy, because one is alive, one exists, has a purpose, has a sense" (PCM).

Finally, in the discourse the valuation of the orientation toward transcendence, whether religious or not, was observed. "... to me happiness is related to God, then I know that everything happens with a purpose ..." (SCW). This element was intense in the Chilean sample, and it was practically not mentioned in the Italian sample.

In general, the positive disposition toward life was emphasized in the discourse of the professionals.

The Social Representation of the Vital Experiences Source of Happiness

Two large types of vital experience source of happiness were recognized: experiences of satisfaction by susception and of satisfaction by realization. Both experiences are given as cathexis, i.e., by making contact with a satisfier (a good from the subjective standpoint). On the other hand, each of these experiences can have different scopes which go from the strictly individual to the collective.

Experiences of Satisfaction by Susception (ESS)

Experiences with a pleasing emotional tone that occur upon receiving a good that can suppress a state of restlessness (because of the lack of something) or by increasing the current state of pleasure. For example: satisfaction of basic needs, receiving affection, receiving social consideration, enjoying everyday things, feeling loved by God.

The ESSs have in common the receptive role of the person. An important group of them is composed of the assimilation of satisfiers that satiate basic needs or demands for the context. "... I feel that I am a happy person because I feel loved by my family and friends" (SCW).

In these experiences what is protagonical is the sensitivity and sensoriality of the individual. "... the somatic" (PCW); "but of course, the body" (PCM).

It is also the typical response of enjoyment in everyday life. "... it can come from a simple family supper, listening to a song... the important thing is to know how to enjoy it fully ...and not let it run away" (SIM).

The ESSs are not necessarily linked with bodily hedonism, they can also be linked with spiritual experiences. "... to me happiness is... to be spiritually connected with God" (SCW).

They can also be the consequence of a pleasant consumption or of the reception of something valued. "...there are so many degrees of happiness, one can be pleased, perhaps not happy, for having bought, I don't know, a dress that I liked very much..." (PIW); "... the other was the second goal by Salas against Italy in 1998... because I was crying of happiness" (SCM); "... the pleasures... for example, eating tasty food, I don't know, drink [alcohol]... not only in the sexual issue" (SCW).

Experiences of Satisfaction by Realization (ESRs)

Experiences with a pleasant emotional tone that occur when a person has succeeded in fulfilling what it aimed at or in getting involved actively in what it values. For example, to achieve a goal, make a good performance, provide a service to others, or learn something through an effort.

The ESRs can be described through judgements of achieving or getting something significant. "... I had a good time at work, I liked what I was doing, but I was not happy because it was not what I wanted to do in my life, I wanted to go to the university. I had many happy moments, but I was not happy until I succeeded in entering here" (SCM).

The ESRs occur with the execution of an active behavior, i.e., the person is empowered and acts on reality in order to do what it values. "... achieve my objectives..." (SIW).

The ESRs include the intrinsic enjoyment of the activity. "... for example, I practice sports and when I compete, regardless of whether I win or lose, I feel happy because I competed, because I gave everything I could give, and to me that is being happy" (SCM). In this way an ESR can or cannot be linked to the satisfaction of achievement.

Typical contents are realization in significant aspects of the personal life project and feeling useful. "... I'm not happy if I don't have something to do, I feel useless" (SCM); "realize myself at the professional level" (PIW).

The experience of reciprocal love falls into this category, as an activity that takes place jointly with others. "... having a profound sentimental relation ... also with my friends ... a family..." (SIW); "Love and be loved" (SCM). "To me it is love, in its wide sense, relational" (PIM). This constituted a high intensity content in all the discourses.

Considering both types of vital experiences source of happiness, the ESRs stood out in the discourses of students at the time they referred to their life projects, specifically in the Italian sample they referred to the achievement of goals. On the other hand, the ESSs in the realm of enjoyment of the everyday were highlighted by Chilean students as well as professionals.

In the affective plane the ESSs were more evident among the students of both countries, while among the professionals the allusions to the love plane consisted in ESR type responses.

The persons mentioned that for both kinds of experiences (ESS and ESR) the presence of expectations (whether reception or realization) can generate an ambivalent emotional tone, becoming a source of either pleasure or tension. In other words, fulfillment of the expectation does not necessarily guarantee the experience that has been projected in it, turning into a source of frustration. "... what happens to me is that I have certain objectives, I achieve them, and instead of feeling happy I realize that I feel even more dissatisfied, because I imagine an ideal, but I am happier imagining the objective than after I have reached it..." (SIW). The persons can also relate with their expectations or goals in an obsessive and anxious manner. "... what happens to me is that the scope of the success makes me anxious, and therefore does not make me happy..." (PIW); "... if I have an objective and that absorbs all my life, then I get lost" (PIW).

Scope of the Satisfaction Experiences

In the discourses it was seen that the ESSs as well as the ESRs can have an individual or collective scope. The former are aimed at the direct satisfaction of oneself (my enjoyments, pleasures and achievements). Here we also include the satisfaction of persons from the more significant surroundings, like the family, that constitute an extension of oneself. "... achieve all my yearnings and desires, material... as well as personal expectations ...in addition to having good social relations ... and health..." (SCM). On the other hand, the experiences with a collective scope refer to the satisfaction that is obtained from verifying the well-being of those who are outside the direct surroundings. "... I would be happy if all the people were happy, then there is something that has to do with a feeling of transcending individuality..." (PCW).

Crossing the types of experiences according to their scopes and the kinds of conduct of the person in satisfaction, four types of vital experiences source of happiness can be obtained: a) Experiences of satisfaction by susception with individual scope; b) experiences of satisfaction by realization with individual scope; c) experiences of satisfaction by susception with collective scope; and d) experiences of satisfaction by realization with collective scope (see Table 5).

Finally, the discourse in both countries was focused on verbalizations restricted to the individual. Some professionals stressed the importance of the experiences of satisfaction by susception and realization with collective scope.

Discussion

Dialoguing with the literature it is possible to see that the vital experiences of satisfaction by susception and realization reflect a balance in the attribution to eudaimonic and hedonic experiences as causes of happiness. This combined trend had already been detected by Javaloy (2007) in his studies of subjective welfare with Spanish youngsters. Even so, ESRs centered on achievement stand out among the students, i.e., among the younger people. In the Chilean sample the ESSs by affective receptivity are preponderant, while in the Italian sample they express more strongly the individual type ESRs. The collectivism-individualism dimensions allow the interpretation of these differences (Lu and Gilmour, 2004). According to the studies of Hofstede (2011), from the values standpoint Chile is a collectivist and feminine country, while Italy is individualist and masculine. This helps to understand that in Chile there is an orientation more centered on relations and affections and in Italy more focused on achievement and individual realization. The above agrees with the study of Sotgio et al. (2011) on subjective representations in Italy and Cuba, where they found that most of the attributions to happiness in Italian older adults referred to the sphere of personal interests, while Cubans (collectivist culture) seemed more centered on relational and emotional aspects of life.

On the other hand, the SR of the conditions and vital experiences source of happiness express a passive-active polarity. In the passive pole a happiness with a hedonic orientation nourished by ESSs is configured. These hedonistic experiences of receptive-passive generation include gratitude, spiritual ecstasy, sensory enjoyment, the contemplation of beauty, feeling loved, among others. In the active pole, on the other hand, a eudaimonic happiness fed by ESRs is configured, where abilities are used and development takes place. They include the pleasure to learn, creativity, the flow or compenetration with the activity, generosity, enthusiasm, optimism, altruism, etc.

An interesting finding is that one part of the sample estimates that to be happy it is necessary to have a benign environment for oneself and for the loved ones. Another part emphasizes the need for a perfect environment where only positive events take place (common in students, i.e., young subjects). It would be worthwhile to investigate whether the condition of a benign environment points at a subjective representation of happiness as welfare (global, subjective and stable) and whether the condition of a perfect environment is aimed more at a notion of emotional happiness (high intensity positive emotion).

One of the objectives of the research was to compare the SRs of the sample of socializing agents in quality of life with the empirical and theoretical contributions of positive psychology. As already mentioned by some authors, happiness has a positive effect on people (Veenhoven, 1984; Javaloy, 2007). In this sense, a positive attitude is seen in the discourse of the participants toward satisfaction experiences, more than toward happiness in itself, which many times is considered a utopia (Rodríguez, 2011). The satisfaction experiences are attributed a positive feedback to the individual. For example, reference was made as to how achievement experiences give a feeling of control over one's own life, increase personal confidence and the feeling of worth.

The SR of the participants also considers a large number of constructs that positive psychology has related with happiness and its increase, among them resilience, empathy and internal control locus (Veenhoven, 1993; 2005); the importance of deliberate activity over living conditions (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005); activities like expressing gratitude; cultivating optimism; avoiding overthinking; practicing kindness; concern for relations; developing strategies for confronting; learning to forgive (only Chile); practicing activities that generate flow, i.e., that involve absorption, intrinsic motivation and optimum experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000); savoring the joys of life; commitment with one's own objectives; practicing religion and spirituality; and caring for the body (Lyubomirsky, 2008). There is no direct allusion to the need to identify and cultivate character strengths (Seligman, 2003).

Then it is seen that in the participants the discourse is centered on one's own welfare and that of the loved ones, without greater inclusion of the truly collective plane. An analysis of the three itineraries of happiness model (Seligman, 2003) shows in the SR of the sources of happiness a consistent narrative of actions oriented at a committed life (commitment with personal objectives) jointly with a life of pleasure (hedonic enjoyment), and scarcely at significant life (commitment with welfare beyond oneself and the significant others). This is reflected in a low consideration of the identification of strengths and their use in actions that involve a good and development for the others. The above is a weakness that can be corrected in the formative plans of these professionals.

Another interesting aspect of the results is the ambivalence of the satisfaction experiences. Thus, having goals and working for them is a source of tensions and dissatisfaction. Already Kasser & Ryan (1993) and Ryan & Deci (2001) stated the above, showing that objectives like fame, money and beauty are a source of more frustration than happiness. On the other hand, Csikszentmihalyi (2000) has documented that when activities are performed whose challenges and level of difficulty exceed the person's skill level, anxiety is produced.

Finally, the sample group considers psychological capital as a key aspect in happiness. However, in spite of considering a large number of factors that are consistently related with subjective well-being, they are not consciously articulated in a process, but rather as a collection of elements related to one another. In this agglutination of causes and factors, the scope and limits of the ability to bring about one's own construction of happiness are not quite clear, and neither is the conscious and intentioned use of the strengths of character, how flow experiences are generated or a significant life constructed.

Conclusions

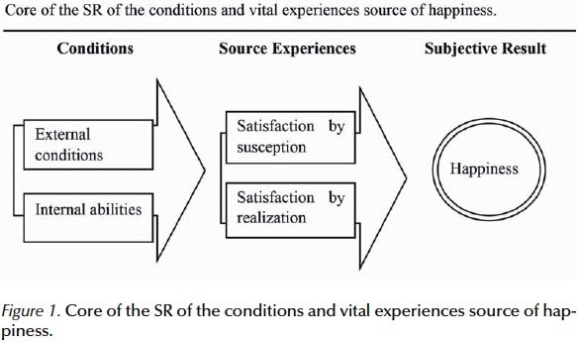

It was possible to reconstruct a consistent and shared symbolic core of the SR of the conditions and vital experiences source of happiness in the samples of students and professionals in the areas of health and education from both countries (see Figure 1).

In this way, the discourse articulates that given the external and internal conditions for happiness it is possible to produce vital experiences of satisfaction by susception and by realization that lead to happiness as a subjective result.

The contents of the SR did not differ qualitatively according to gender, but they did in the case of the roles (students and professionals) and by country. However, we have to be careful at this point, in view of the characteristics of the sample: a greater proportion of women than men, a greater number of students than professionals, access to the latter exclusively through focus groups (in contrast with the students, who also answered a questionnaire), and access to the Italian sample one year after the Chilean sample.

As to the external conditions, this core is centralized on affection, close and satisfactory interpersonal relations, together with the freedom to be and development. Except in the aspect of affection, the Italian sample expresses intensely demands from the context, in contrast with the Chilean. However, with respect to the internal conditions, the psychological capital has more strength than the attributions made to the context. In this sense, the Chilean sample elicits resilience, the ability to face and accept adversity in a particularly noticeable way. In both countries intense eliciting of the abilities for assertiveness of the self is seen in the students, while the professionals emphasize more the ability to stress the positive of life. Considering the whole discourse, highlighted the preponderance of the abilities for assertiveness of the self, the construction of positive interpersonal relations, and stressing the positive of life stand out.

At the level of vital experiences source of happiness, a combination of reaching goals and achievement (ESR) with the receptiveness of affection and the enjoyment of everyday things (ESS) is seen.

As a recommendation, considering what has been presented in this article, it is suggested to develop training programs in positive psycho-education for health and education professionals, starting at the undergraduate level, aimed at the understanding and promotion of experiences with a hedonic and eudaimonic scope, as well as reinforcing the psychological capital.

Among the recommendations for future research, it is suggested to complement the data analysis with a register of content according to frequency based on characteristics of interest in the samples, particularly as a function of sex, age and origin, expanding also the equitable representation of participants to facilitate the identification of representations and meanings particular to and/or frequent in each group. It would also be interesting to incorporate as data collecting techniques the use of natural semantic networks, considering their easy application and analysis, to complement a research carried out through interviews and focus groups.

A detailed comparison of these and other results obtained in Chile and in Italy will be presented in a later article.

References

Abric, J. (1984). A theoretical and experimental approach to the study of social representations in a situation of interaction. In R. Farr & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Social Representations (pp. 169-184). London: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Fluir: una psicología de la felicidad. Barcelona: Kairos. [ Links ]

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.95.3.542. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Kesebir, P., & Lucas, R. (2008). Benefits of Accounts of Well-Being-for societies and for Psychological Science. Applied Psychology: Health & well-being, 3 (1), 1-43, available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00353.x. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Suh, E., Luca, R., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 271 - 301. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.125.2.276. [ Links ]

Duckworth, A., Steen, T. & Seligman, M. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629-651. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154. [ Links ]

Fisher, C. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12,384412. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.14682370.2009.00270.x. [ Links ]

González, F. (2008) Subjetividad social, sujeto y representaciones sociales. Revista Diversitas-Perspectivas en Psicología, 4, 225-243. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2011). Geert Hofstede Cultural Dimensions. Downloaded on June 13, 2011 Site http://www.geert-hofstede.com. [ Links ]

Javaloy, F. (Coord.) (2007). Bienestar y felicidad de la juventud española. España: INJUVE. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1984). La representación social. Fenómenos conceptos y teorías. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Kasser, T. & Ryan R. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410-22. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410. [ Links ]

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004) Cultural and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 269-291. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8789-5. [ Links ]

Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). La ciencia de la felicidad. Barcelona: Urano. [ Links ]

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111-131. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111. [ Links ]

Moscovici S. (1993). Psicología social II. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

New Economic Fundation. (2009). The Happy Planet Index 2.0. Downloaded on November 15, 2009 Site http://www.happyplanetin-dex.org/public-data/files/happy-planet-in-dex-2-0.pdf. [ Links ]

Páez, D. (1987). Pensamiento, individuo y sociedad: Cognición y representación social. Madrid: Fundamentos. [ Links ]

Reyes-Jarquín, K. & Hernández-Pozo, M. (2012) Análisis crítico de los estudios que exploran la autoeficacia y bienestar vinculados al comportamiento saludable. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues, 3(2), 5-24. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.5460/jb-hsi.v3.2.29915. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M.J. (2011) Representación social de la noción de felicidad: un estudio transcultural en muestras calificadas de estudiantes universitarios y profesionales de las áreas de la educación y la salud en Chile e Italia. In Jesús Redondo (Editor) in Tesis Doctorales en Psicología, Compendio 2011. Colección Praxis Psicológicas. Universidad de Chile. [ Links ]

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2001) On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Anual Review of Psychology, 52, 141-166. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [ Links ]

Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [ Links ]

Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13-39. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0. [ Links ]

Salazar, M., & Herrera, M. (2007). La representación social de los valores en el ámbito educativo. Investigación y Postgrado, 22, 261-305. Downloaded on July 19, 2009 Site http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/pdf/658/65822111.pdf. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. (1998). Learned optimism. New York: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. (2003). La autentica felicidad. Barcelona: Vergara. [ Links ]

Sisto, V. (2008). La investigación como una aventura de producción dialógica: La relación con el otro y los criterios de validación en la metodología cualitativa contemporánea. Psicoperspectivas, VII, 114136. Downloaded on January 9, 2009 Site http://www.psicoperspectivas.cl. [ Links ]

Sotgio, I., Galati, D. & Manzano, M. (2011). Happiness components and their attainment in old age: a cross-cultural comparison between Italy and Cuba. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 353-371. Available via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9198-6. [ Links ]

Taylor, S., & Bogdan, R. (1987). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación: La búsqueda de significados. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. [ Links ]

United Nation Development Programme (2011). International Human Development Indicators. Available via http://hdr.undp.org/en/data/profiles. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T. (2000). Ideología: Una aproximación multidisciplinaria. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of Happiness. Downloaded on June 13, 2011 Site http://www2.eur.nl/fsw/research/veenhoven/Pub1980s/84a-con.htm. [ Links ]

Veenhoven, R. (1993). Happiness in Nation. Downloaded on June 13, 2011 Site http://www2.eur.nl/fsw/research/veenhoven/Pub1990s/93b-con.html. [ Links ]

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Apparent quality-of-life in nations: how long and happy people live. Social Indicators Research 71, 61-68. Available via: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8014-2. [ Links ]

Veenhoven, R. (2011). The Word Data Base of Happiness. Available via: http://www.world-databaseofhappiness.eur.nl. [ Links ]

1 In view of the asymmetry between the proportion of participants by sex and the lack of identification of qualitative differences between them, no comparisons by sex are included in the results.

Self-references for authors: 1.

Self-references for the JBHSI: 1.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

María José Rodríguez Araneda.

mariajose.rodriguez.a@usach.cl

About the author:

Name: María José Rodríguez Araneda. Degree: PhD in Psychology, Universidad de Chile. Affiliation: Universidad de Santiago de Chile, school of psychology, associate professor. Line of research: Meanings of happiness, ethics, quality of life, social and organizational psychology. Address: Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Av. Ecuador N ° 3650, third floor, Commune of Estación Central, Región Metropolitana, Chile. ZIP code 9170197. E-mail: mariajose.rodriguez.a@usach.cl.