Introduction

The study of motivation is of prime importance for designing policies for promoting tourism aimed at particular segments of the market (Herold, Garcia & DeMoya 2001; Clift & Forrest 1999; Lang & O´Leary 1997), as well as the creation of new products and tourist attractions to attend motivational demand (Prideaux & Kininniont 1997; Laws 1998). According to Castaño, Moreno & Crego (2006), motivation explains the reason for travel, the choices made and the level of satisfaction of tourists.

Although tourist motivation has been widely examined, there are few published scientific articles related to travel to island destinations (Qiu & Lam 1999;Jönsson & Devonish 2008; Liu, Lee, Kan & Huan 2011) focused in low season or off season (Kozak & Rimmington 2000). Studies have related motivation with nationality (Kozak 2002) or with market sectors using various different criteria (e.g.Lee, Lee & Wicks 2004; Park & Yoon 2009; Devesa, Laguna & Palacios 2010; Kassean & Gassita, 2013).Shoemaker (1994) established segments among tourists according to the perceived benefits of the destination and motivational influences related to adventure, fun, family, among other factors. These studies have been carried out in Europe, Australia and Asia, and to date there are no empirical studies of motivation in the choices of island destinations made by nationals of Mexico or USA. A better understanding of tourist motivations can assist in the development of some strategies (Valenzuela, 2015) for managing seasonality to encourage visitation.

In the case of the island of Cozumel, Mexico, it is in the mature stage of its development and tourism represents the main economic sector, without diversification. The low season represents a challenge and identifying the factors which influence the choice of destination allows the evaluation of current strategies for tourism promotion to see whether it is directed at the right market segment in the low season, and whether it is achieving the intended impact. The knowledge generated by the present study may influence tourism related decisions on widening the target market segments, planning promotion strategies, improving the competitiveness and diversifying the services offered. Motivations´ study is fundamental to understand tourists’ decision process in choosing a destination.

This study seeks to answer the question: What is the main motivating factor which influences the decision to choose Cozumel as a destination in low seasons? It is hypothesized that the principal motivating factor which influences the decision to choose Cozumel as a destination in the low season is the availability of water sports (diving and snorkeling).

Motivational factors

Leontiev (1978) argued that any motive observed as action or behavior, reveals the motivation, but in general people are not conscious about this because activities are socially developed. In tourism, personal motives can explain the activities and behaviour of visitors, and are considered to be forces which may be external or internal (social or personal), while motivation is individual and cognitive (Pylyshyn 1986) and comes from a deeper level to connect motives with specific psychosocial objectives.

For Gnoth (1997), motives are durable dispositions that are repeated cyclically. For example, during holiday seasons, the social environment promotes trips, while the motivations set some specific preferences, such as going to the beach or visiting a museum. Therefore, motives guide the generic organization of behavior and a certain direction, but the motivations establish specific objectives that are directly linked to satisfaction (Castaño et al., 2006).

In a similar way, for Crompton (1979), motivation refers to a need that drives an individual to act in a certain way to achieve the satisfaction. Beerli & Martín (2004) hold that motivation is the necessity that impels people to act in a certain way to achieve desires. In the tourism sector, motivation is considered to be a combination of factors which explain the reason why tourists wish to buy a product or service (Swarbrooke & Horner 2007), or alternatively the preferred activities or behaviours which determine the degree of visitor satisfaction.

Studies of motivation in tourism have been carried out by Crompton (1979), Dann (1981), Pearce (1996), Ryan (2003) and others. According to Dann (1981) the motivation to travel arises from a combination of intrinsic (psycho-social) factors, and extrinsic (cultural) factors, and the combination of these intrinsic (push) and extrinsic (pull) factors is unique to each individual. Pearce (1996) suggested a theoretical framework for understanding motivation which differentiates intrinsic (push) and extrinsic (pull) motivation and proposes a hierarchical classification of motivations. For Ryan (2003) travelers are motivated by a desire to leave a place (push) and a desire to see another place (pull). Summarising, people travel because they are pushed by their internal motives and pulled towards a destination by external factors (Lam & Hsu 2006).

Crompton’s study (1979) proposed a multi- casuistic explanation model for tourism motivation with two types of dynamic and complementary forces which may be described as “push and pull”: 1) socio-psychological and 2) cultural. The first related with intangible social or emotional personal factors (“Push”) and the second with tangible aspects of destinations (“Pull”), for example landscapes. Push factors are seven: 1) relaxation, 2) exploration and evaluation of self, 3) escape from routine, 4) regression, 5) facilitation of social interaction, 6) prestige and, 7) enhancement of kinship relationships; and have origin in the individual needs for escape from routine, stress, and alienation. Pull factors are two: 1) novelty (include adventure, new experience, curiosity, adventure, and related) and 2) education; both with characteristics of the social context that influences people to choose a destination with specific characteristics, as historic places, museums, snow mountains, sun and beach, or other places. Destination characteristics have a critical role to attract tourists motivated with pull factors.

The “push and pull” model (not similar to push & pull marketing strategies, that are promotional techniques used to get the product to its target market) has been used in studies to understand the motivations of tourists (e.g. Hanqin & Lam 1999; Kozak 2002; Kim, Sun & Mahoney 2008; Yoon & Uysal 2005; Devesa, Laguna & Palacios 2010). These studies focused on the choice of destination, the comparison of motivations by nationality, specific age or activity market segments, and perceptions of satisfaction and quality.

For Crompton (1979) and Fodness (1994), motivation´s dimension can be based on cultural, social, personal, educational or utilitarian grounds, while other classifications refer to weather, escape/relaxation, adventure and the self (Bansal & Eiselt 2003; Beerli & Martin 2004). Hanqin & Lam (1999) make reference to knowledge, prestige, human relations, relaxation and novelty. In the work of Botha, Crompton & Kim (1999), the motivations identified were social/personal pressure, social/prestige recognition, socialization, self-esteem, regression, novelty, distance from the crowd and learning/discovery. For Mak, Wong & Chang (2009) the factors were friendship and kinship, health and beauty, self gratification and indulgence, relaxation and relief, and escape, whileYoon & Uysal (2005) identified “push” factors such as emotion, relaxation, personal achievement, family time and escape.

According to Eftichiadou (2001), quantitative studies on motivational factors may be summarized with this: people are different and could be classified into segments according to ranges of motivations and a combination of “push” and “pull” factors, with individual and social motives, influenced by individual knowledge or experience (Pearce 1993, McCabe 2000), or multiple psycho-social necessities, calling for a multi-dimensional analysis.

Study Case

Cozumel is an island located in the Mexican Caribbean, and its economy is mainly dependent on tourism as there is no industry (INEGI 2012). The main attractions for the island include diving, snorkeling, beach activities, relaxing, archeological zones and Mayan people as local hostess. More than 40% of visitors are repeat visitors (SECTUR 2009), indicating a high level of loyalty. Other sectors include day trippers using the ferry from the mainland, which are probably not repeat visitors although there is a lack of information to support this.

Tourism activity on the island is mainly seasonal (API 2012; SEDETUR 2012), measured with the number of tourists (arrivals). In 2011, Cozumel received 475,837 tourists (SEDETUR 2012), of which 441,692 arrived by plane (ASUR 2012), men or women, national or foreign, dominated by the country segment of USA, Mexico y Canada, as main issuers in different times of the year. Seasonality is concentrated in three main periods: summer, winter and Easter, due to public and school holidays. On the other hand, low season periods are mainly between September and October. The island is not big enough and lacks sufficient attractions compared with world destinations to attract other tourism segments, so that promotion strategies should concentrate on adequate motivation to attract visitors in different season and favour repeat visitors, avoiding negative fluctuations of demand, the inefficient use of resources and labour market (Baum et al. 2001).

The profile of tourists visiting Cozumel provides that accommodation average is 3.7 nights’ with an estimated spending of $538.00 USD (SEDETUR, 2012), an average age range of 26 to 55 years, with a trend towards mature age. As companion in the trip, 29% comes with spouse or couple, 38% with family, 14% with friends, 17% travel alone and 2% with people related work. 56% travel to Cozumel with a package tour (SECTUR, 2011).

According to SEDETUR (2012), the lodging structure consists of 45 hotels in different categories, mainly marketed as bedrooms (75%) and timeshare (25%). Most of the local economically dependent population (53%) provides services in any company directly related to tourism (INEGI, 2006), so the high seasonality of tourism is a recurring problem for the entire destination. In addition, irregular cycles weakens labor quality tourism services, and tourism companies make short term plans, which negatively impacts the competitiveness of the destination and the visitors’ satisfaction level (Amaya, Zizaldra & Mundo, 2015).

Methodology

A finite formula, applied when the population size is known, was used to determine the sample size needed to achieve a 95% level of confidence for a survey based on the 475 837 tourists who stayed in Cozumel in 2011 (SEDETUR 2012), and the calculation yielded 420. A survey instrument was piloted with hotels belonging to the Asociación de Hoteles de Cozumel (Cozumel Hotel Association) over a period of 30 days. The survey questionnaire in its final form was applied to 520 tourists in the departure lounge of Cozumel international airport between September and October 2012, to take into account the effects of low season. Of the 520 questionnaires applied, 493 valid responses were usable for analysis.

Data were collected using a four-part self-administered questionnaire written in English and Spanish, specifically directed at tourists, male or female, national or international over 18, who stayed at least one night on the island, during low season. The questionnaire design was adapted from previous researchers’ work, such as Hanqin & Lam (1999) and Kim & Lee (2000), and divided into generic questions to collect demographic information (sex, age, country of residence), other general characteristics (period of stay, transportation used, type of accommodation and mode of organizing the trip), and structured sections according to seven factors: I) Personal, II) Health, III) Friendship, IV) Destination attributes, V) Social, VI) Activities, and VII) Tourism activities. The push and pull items were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging through 1 (not important), 2 (hardly important), 3 (important), 4 (quite important) and 5 (very important).

Reliability test was conducted, and the result of Cronpach’s Alpha was 0.8533. The internal consistency of the instrument was determined by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the unobservable factors (motivations) constructed from the observed variables. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of under 0.7 is considered unacceptably low (George & Mallery, 2003; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained was 0.87 with 42 variables (from 45 items, some generic questions were excluded from the analysis), representing a high level of internal consistency and indicating that the questionnaire items were relevant for measuring travel motivation. Only three variables: gender, age and residence, were eliminated following the results obtained from the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (as a normal procedure).

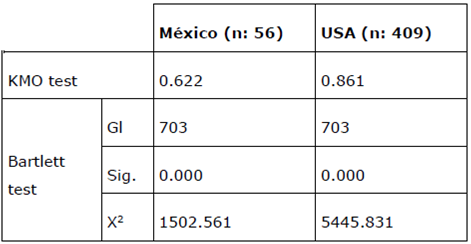

A Káiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and a Bartlett test were applied to confirm the selection of a factorial analysis. In the case of a KMO test, a score of over 0.5 is the minimum appropriate, and values between 0.7 and 0.8 indicates that is acceptable, and values above 0.9 are superb for a factor analysis (Kaiser, 1974).

In Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Bartlett, 1950), a significance (Sig.) of under 0.05 confirms the validity of a factorial analysis. To apply these tests, categorical data (sex, age, number of nights stayed, tour packages, timeshare, and transportation) were eliminated from the data. Both tests validated the use of factorial analysis for tourists from Mexico and the United States, although the Mexican sample was limited in size (Table 1).

A factor analysis test was applied to bring observed variables under more general, latent or unobserved variables (called factors), to reveal the internal structure of a large number of variables (Rietveld & Van Hout, 1993). In general, this is the most common type of factorial analysis for identifying the subjacent structure in a group of variables. Results were obtained using an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) method of principal components, eigenvalues greater than 1, with 150 iterations for convergence; rotation Varimax with solution rotated to 150 interactions and sedimentation graphics, as recommended by Nunnally & Bernstein (1994).

Rotation Varimax generates a matrix which allows a simplification of factors, to facilitate understanding the results within a more comprehensible pattern, without changing the proportion of explained variance in factors (Nunnally & Bernstein 1994). The largest simplifications are 1 and 0 and in extreme cases -1, indicating the positive or negative association between variables of factors (or the contrary, the absence of association when the result is 0). The best positive association is 1. Factors are hypothetical constructs or concepts not observable directly (such as motivation), deduced from correlation among variables.

The factorial analysis begins with a correlation matrix with variables and commonalities. These last are the proportion of variance explained by common factors, whose initial values are 1, and are important because when the result is close to 0, it means that those variables do not explain or not fit in the model. On the other hand, when the result is close to 1, then the variable will be fully explained by common factors that appear in the matrix. It is a measure of how well the model fits with the variables and data obtained.

Finally, a Cramer's V test was carried out with selected variables: country, sex, snorkeling, and diving, to find any association among dichotomous variables, after a Chi-square had determined significance. This test is used to calculate correlation in tables with 2x2 rows or columns, and its result varies between 0 and 1. Close to 0 shows little or no association between variables while figures close to 1 indicate a strong association.

Results

Most of the 493 tourists taking part in the survey came from the USA. There were 409 questionnaires returned by USA citizens (83%) and 56 (11.3%) by Mexican citizens. Part of the sample (5.7%) came from Australia, the Czech Republic, England, India, and Israel. Factorial analysis requires at least 50 members of a group, and as this group did not reach the threshold number, the analysis was carried out with data from Mexican and USA respondents.

The average age of participants in the survey was 45. The mode of the sample was 50 years old and ages ranged from 18 to 78. There was no statistically significant difference in the numbers of each sex in the sample. Of the Mexican participants, 29 were female and 27 were male, while 212 USA participants were women and 197 were men. The majority of the USA participants (213) stayed in Cozumel for 7 nights while Mexican tourists stayed only two or three nights. There was no significant difference between USA and Mexican tourists in their level of preference for package tours. The majority of tourists sampled (55%) did not buy package tours, and 75% (n: 493) of both nationalities did not stay in timeshare accommodation.

Table 2 presents the top 10 reasons given for tourist travelling from USA and Mexico, in decreasing order of frequency.

Table 2 shows that although participants from both countries share some motivations, they are not given the same importance in deciding on a destination. For USA tourists, the principal motivation is having fun (mean 4.63), while for Mexican tourists it is the natural environment (mean 4.63). To establish a common pattern, owing to the diversity of impulses to visit Cozumel, responses were grouped in dimensions (common factors) following an exploratory factorial analysis to determine the motivations that influenced participants.

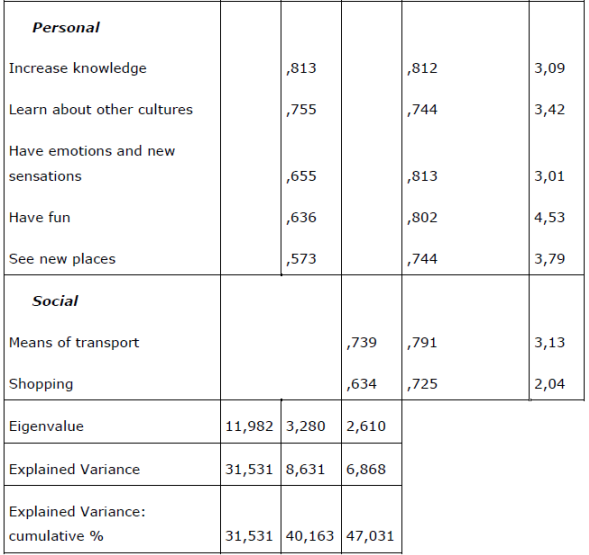

Table 3 shows the factorial analysis of Mexican tourists’ motivations. According to the analysis, there are three principal factors (F1-3) with a total cumulative explained variance of 47.03%, showing that these components are highly relevant for Mexican tourists. The Destination dimension contains 31.53% of the motivations of Mexican tourists for visiting Cozumel (Eigenvalue: 11,98), while the Personal dimension has 8.63% and the social dimension contains 6.86% of the motivations. Questions related to physical relaxation, price of transportation, landscapes, and cultural attractions gave responses in two factors and can be considered two-dimensional, while questions about seeing new places and social environment gave responses in three factors and can be considered three-dimensional. In these cases several motivational impulses may act at the same time on decisions taken regarding travel.

Table 3: Factorial analysis of the motivations of Mexican tourists

(Results less than F= ,500 are not included)

The Table 4 shows that for USA tourists three factors represent 35.57% of the cumulative explained variance. The Destination dimension contains 22.09% of the motivations of USA tourists for visiting Cozumel (Eigenvalue: 8,39), while the Personal dimension has 7.58% and the Social dimension contains 6.86% of the motivations in the rotated factors column. Questions related to reducing stress, cultural attractions, landscapes, social environment and physical relaxation can be considered two dimensional. There were no three dimensional factors in the data.

Table 4: Factorial analysis of the motivations of USA tourists

(Results less than F= ,500 are not included)

The analysis shows that for both Mexican and USA tourists the common motivational factor for traveling to Cozumel is the destination. While both groups coincide in the main factors, the importance given to each factor varies. In this study it was hypothesized that the principal motivating factor which influences the decision to choose Cozumel as a holiday destination is the availability of water sports (diving and snorkeling). The data obtained for Mexican tourists show a very low total variance (5.29%) for the motivational influence for these activities (diving 0.311 and snorkeling 0.693 in the rotated factors data). The hypothesis is therefore refuted and the null hypothesis accepted. In the case of USA tourists, the rotated factors data also give low values for snorkeling (0.466) and diving (0.721), so that the null hypothesis is accepted for this group too.

Discussion

This study assumed that Cozumel was chosen specifically for vacationing, for 409 questionnaires returned by USA citizens (83%) and 56 (11.3%) by Mexican citizens, because tourists had an associated motivation established previously to the travel, which influences their behaviour, but it must be recognized that some aspects may have been overlooked, as it is impossible to consider every aspect related (Krippendorf, 1987). About 35 to 47% (Table 3 and 4) of the variance was explained by motivation in the current study, so future studies should incorporate other variables. Nonetheless, this research does contribute to the limited availability on island tourist motivations across countries.

The study revealed that the same broad factors for both sample groups were found (Table 2), albeit with variations within these, based on nationality, which is consistent with studies previously mentioned (Kozak, 2002; Pizam & Sussman, 1995) . According to Crompton (1979), USA tourists have a strong regression (psychosocial) motivation to travel to Cozumel and Mexican tourists have a strong escape motivation (psychosocial). It was found that USA tourists rated highest on ‘‘having fun’’ which is consistent with Kozak (2002) and Jönsson & Devonish (2008) findings. In the other hand, Mexican tourists were found to be interested in natural environment. Other studies are needed to eliminate possible explanations about socio-demographic variables that could be a reason for differences between nationalities.

Tables 3 and 4 have similarities in “Facilitation of Social Interaction”, that are push attributes which trigger the need to travel, but are not enough because Security and Accommodation are essential to choose a specific destination. Cozumel has an image of friendly and hospitable local people, and this suggests that visitors associate island tourism with security, friendly hosts and comfort, attributes usually connected with house and family.

Results from Tables 3 and 4 establish that the combination of push and pull factor -some of them unconscious- seems to motivate tourists, rather than any particular activity such as diving or snorkeling that one might do there. Sex, age and other demographic variables were not found to be determinants of travel decisions in this study. These results confirm to Andreu et al. (2005), which found that tourists´ socio-demographics variables like age had no significant influence on travel motivations. The analysis shows that diving and snorkeling play no significant role in the choice of Cozumel as a holiday destination as neither Mexican nor USA visitors prioritized these activities (see Table 4). However, this result was obtained at one particular time of the year, and it is possible that a survey conducted in a different period may obtain different results.

Possible correlations of variables such as sex, country, snorkeling and diving were explored. The Cramer´s V test showed that for the sample (n: 493) there was no significant relationship between country of origin and snorkeling, but there is a difference (Cramer 0.149 and Sig. 0.028) for diving and country. Also, there was a relationship between sex and diving (Cramer 0.204 and Sig. 0.000) which shows a preference of men for diving. In all cases, the results show a very low level of association among these variables. This result partially confirms Andreu et al. (2005) research, which male tourists look more for recreation in the destination.

The sample was based on tourist from the USA and Mexico as the main discriminating variable for explaining the motivational differences. This could be a limitation of the study, but marketing efforts are directed to geographical zones. Moreover, national cultures could have specific patterns of motivation that affect an individual’s decision to travel (e.g. Kim & Prideaux, 2005).

Data was collected at one time measurement (a cross sectional data) to people traveling to Cozumel only by plane. This may cause possible non-representation for tourists arriving by ferry docks, which are few but should also have been interviewed, so future models could understand tourist motivation better. The sample of respondents was found to be over-representative of one geo-demographic group. However, this segment (USA) is the major purchaser of Cozumel destination packages in every season of the year.

Studies about tourist motivation in Mexico are notorious for their absence, so research directions have to consider contemporary circumstances which create or influence the process of motivation, considering tourism within a system framework where destinations and regions are connected by several types of linkages. Major additions should involve the inclusion of team and social group as well as families, in addition to individuals and couples, pre-trip expectations, the season chosen, whether participants come from urban or rural environments. The demographic aging process taking place in industrial countries may enhance destinations prepared for older adults. Ethnic contextual factors that influence decisions should also be considered. These may turn out to be important variables in determining motivational factors for different tourism segments.

Conclusions must be restricted with an exploratory factor analysis, but data gathered from survey reveals that Crompton theory (1979) is supported by evidence and that tourist motivation has a psico-social origin and Cozumel is a cultural destination where the regression, escape or facilitation of social interaction are more significant, but security, weather and accommodation are also important conscious factors for the final decision. So, tourists are guided by internal factors to satisfy their desires but with external factors on where to go, based on destination attributes.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to identify the motivational factors that influence tourists in choosing Cozumel island as a destination, using countries as segments. An exploratory factor analysis was applied and results suggest that for both nationalities, motivation factors are based on: I) Destination, II) Personal and III) Social. The results reflect the fact that in low season, USA tourists desire active experiences at destination, and Mexican visitors, passive experiences.

The discussion indicates that differences in motivations based on countries are a significant factor for island destinations. Sex and aquatic activities variables suggest a weak relation but do not seem to be determinant motivator. The results obtained refuted the hypothesis that the principal motivating factor which influences the decision to choose Cozumel as a holiday destination is the availability of water sports (diving and snorkeling). However, prudence should be used to read these findings, given the limitations discussed. Nevertheless, the results contribute to understanding tourists’ motivations for visiting destinations in Mexico and the Caribbean islands.

These finding can be useful for developing strategies to enhance Cozumel tourism markets and competitiveness, through marketing and improvement of products or services, to attract tourists from specific countries, regions or targets, to maximize destinations associations with motivations, and increase the overall satisfaction.

Motivations of tourists traveling to Cozumel are multi-dimensional, so that more than one factor affects the decision to travel. In this case, the promotion of Cozumel as tourism destination may be focused on one main market segment with the right matching of push and pull motives, but could also take into account related segments as well as offering services that are completely different (for example combining cultural and natural motivations, creating a perception of multi-dimensional product) and in that way reducing dependence on only one market segment for any tourism season.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)