1. Introduction

The structure of the world economy has shown perceptible changes since the 2008 economic crisis. Trade patterns and economic recovery trends among developed and developing countries have shown a shift from conventional order. Currently, developing countries are taking the lead on the global economic recovery with steeper growth rates compared to developed countries.1

Before 2008, the main contributors fueling economic growth were developed economies, having an approximate 70 percent share of total global output.2 In contrast, after the crisis, developing economies have had a steeper growth recovery; increasing their share of global output to an approximate 40 percent.3

Source: Author's calculations based on UNCTADstat, 2016.

*Calculated using GDP in dollars at current prices and exchange rates

These shifts on trade trends evidence that “the world economy has entered a new era in which emerging market economies are the main drivers of global growth”.4 Therefore, developing countries face new challenges to reach growth rates that enable them to become high-income economies, while assuming a role with higher influence on global economic growth. In order to be successful with this transition, developing countries “will need to look to their own domestic political and institutional reform processes […] rather than relying on external commitments as much as they could in the past”.5

However, many middle-income countries seem to be developing below their potential growth rates and have not been capable of moving into highincome levels. Gill & Kharas6 referred to this situation as the middle-income trap (MiT). Since then, diverse approaches to understand the phenomenon and recommendations to escape from it have been developed.

Mexico has been a middle-income country for over four decades but transitioned to upper-middle-income about two decades ago. It is one of the leading emerging economies in the world. Nonetheless, the country has been unable to reach high-income levels, maintaining an average yearly growth rate of 2.6 percent since 1994.7 The existing gap between economic and human development, in addition to the growing competition posed by developing economies, triggered the creation of a political agreement among the three major political parties in Mexico in 2012. The so called “Pacto por México” aims to create and support structural changes through legislative reforms supported by the dominating political parties, which, in turn, can boost growth and development.

This paper finds that according to the literature, Mexico seems to be stuck in the MiT. The objective of this paper is to assess the effectiveness and capacity of three structural reforms undertaken by the current Mexican government to boost growth, following the MiT approach. This paper is among the first ones to make an analysis of the structural reforms implemented in Mexico since 2013-2014 following the MiT approach. The assessment can give an interesting insight to the overall expected results and address identified gaps on the implementation stage.

Despite its length and time limitations, this paper attempts to give a comprehensive assessment of the selected reforms. The first section presents the theoretical approach to the MiT. The second section presents the methodological approach of this paper by establishing a working definition and assessment guidelines to evaluate the three selected reforms. The third section presents a general overview of the latest economic performance of Mexico and provides further detail in the so called “Pacto por México”. The fourth section presents the evaluation of each of the three selected structural reforms according to the assessment guidelines previously established. The final section presents the conclusions of this evaluation.

2. Understanding the Middle-Income Trap

In 2005 Gil & Kharas identified that, up to that point, economic development literature8 did not cover middle-income countries. None of the prevailing models which guided policy recommendations had a specific orientation towards middle-income countries. The recommendations offered were of little benefit and left policy makers without any guidance on their pursuit for transforming their countries into high-income economies.

[The middle-income trap is] a trap of ignorance about the nature of economic growth in middle-income countries: endogenous growth theories addressed the problem in high-income economies (where about 1 billion people live today), and the Solow growth model was still the work-horse for understanding the growth problem in low-income countries (where another 1 billion live), but neither are satisfactory for understanding what to do in countries where the remaining 5 billion people in the world live-those in middle-income countries.9

Gill & Kharas observed some countries growth levels seemed to decline or even stagnate, even though they were a middle-income economy. In general, it seemed that these countries could no longer compete with the low wages of low-income countries, but neither with the high-skilled industries of high-income countries. Gill & Kharas named this particular situation the middle-income trap (MiT).

There is not a specific definition and characterization of the MiT; it “has been loosely used to describe situations where a growth slow-down results from bad policies in middle-income countries that prove difficult to change in the shortrun”.10 There are different interpretations of the term according to the approaches taken, which lead to different policy recommendations. For the sake of clarity, this paper groups the different literature approaches in three main categories: Diverse, Growth Slow-downs and Structural Change.

Diverse: this category can be better understood as a hybrid group. Here can be found all those perspectives which consider the cause of the trap lies either on a lack of convergence to a reference country,11 such as Im & Rosenblatt,12 and Perez13 propose; inadequate human capital development, as the perspective of Jimenez, Nguyen, & Patrinos14 or Mayer-Foulkes,15 or

which include more in depth social and political considerations into their analysis such as the work of Foxley.16 Even though they contribute with interesting positions, their analysis may require more detail. Therefore, this group of literature is kept out of this paper’s scope.

Growth Slow-downs: the literature included in this category discards the existence of a “trap” per se. In contrast, it interprets the MiT as transition periods between income levels which can have growth rate variations. Its proponents find that in some income thresholds growth slow-downs become more frequent, calling for special strategies to boost growth again. As there are growth rate movements, they argue, the term “trap” becomes inaccurate to describe the situation. Therefore, the focus of their research is the effect of long-term growth slow-downs.

Structural Change: this category of literature does find gaps on middleincome countries’ capability to continue their growth path and graduate into high-income economies. Some authors agree on the existence of a new kind of trap; which is different from the already discussed poverty trap.

The category highlights the fact that middle-income countries have special characteristics as they can no longer depend on a low-skill production structure, like low-income countries do, due to their rising costs. Yet, they still have not reached the needed capital and skills accumulation to compete in knowledge-based markets. They interpret the trap as a situation where the lack of appropriate capabilities and structural adaptation seem to be a glass ceiling that keeps the countries from advancing into the next income level. Structural change is the appropriate strategy to overcome this trap as “the continuation of the very strategies that help the countries grow during their low-income stage prevents them from moving beyond the middle-income stage”.17

The prevailing factors found to be related with MiT are an insufficient development of social and productive capabilities, a lack of internal value generation and a high dependence on foreign resources in a context of global interconnections.

3. Systemic Competitiveness

In 1996, Esser, Hillebrand, & Meyer-Stamer introduced the term of systemic competitiveness into the economic development literature. Systemic competitiveness is a result of complex and dynamic interactions between social and economic levels of a national system. The concept stresses the importance of innovation, company structure upgrades and cooperation networks in the process of economic development. Its two main characteristics are the significance it gives to industrial networks and policies that promote their creation and the categorization of a national system into four interdependent levels: meta, macro, micro and meso.

Competitiveness depends on the capacity of a system to create structural changes through a coordinated interaction among levels where “Dialogue is essential for strengthening national innovative and competitive advantages and setting in motion the social processes of learning and communication”.18

Defining the mit Working Definition & Assessment Guidelines

The established working definition for this paper understands the MiT as a specific condition of middle-income countries where they can no longer compete on low-skilled production markets, due to their rising wages. Yet, they have not acquired enough capital, skills or productivity to compete in high-skilled products or become a knowledge-based economy. As a result, “economic growth and structural upgrading become more arduous”.19

This paper considers the income bands, time thresholds and growth rates that Felipe, Abdon & Kumar20 establish on their research as appropriate for moving between income groups. Sharing the structural change approach from the MiT literature, this working definition proposes three main strategies to make the improvements needed. These strategies delimit the assessment guidelines21 used to evaluate the Mexican reforms and are detailed below.

Innovation: in order to escape the MiT, countries should aim to achieve an innovation regime that promotes an industrial upgrade and that leverages their skills and technology usage, through scientific and technological advancements. Gill & Kharas, among others, propose that an innovative environment needs to be supported through special policies that promote competition in open markets, require the use of global standards, create industrial networks, support entrepreneurs and start-ups while encouraging a process of creative destruction.

Industrial Policy: the effects of industrial policies still seem ambiguous due to the complexity of their assessment. Nonetheless, they cannot be detached from almost all outstanding growth and development experiences. The use of industrial policy is an opportunity to initiate an industrial upgrading into activities with higher value added, which require higher skills and access to more advanced technology.

Ohno,22 Paus,23 and Vivarelli24 agree that for an industrial policy to be successful, it is important that the government has the capacity to set its criteria and limits, to monitor adequately the industry performance, reallocate subsidies and restructure the industrial sectors according to the evolution of the comparative advantage. In addition, it also requires a strong leadership which directly monitors the performance of the bureaucracy to reduce rentseeking incentives.

Adequate Financing: for a government to be capable of promoting any of the previous changes, it needs a stable financial source. Tax collection and expenditure budgets are key determinants of the government’s capability to create a structural change of the correct dimension and to maintain it along the middle to long term to guarantee its success.

The existing gaps in the tax collection system limit the capability of the state to increase its collection levels. For this reason, Paus25 recommends that additional revenues should not only be explored on the existing taxes but also on administrative processes and alternative sources.

Deeper financial markets enable an easier access to credit for individuals, small and medium enterprises (sMe) and start-ups, encouraging them to invest in innovation and upgrades. Kharas & Kohli26 state that public-private partnerships can stimulate private institutions to broaden their provision of credit while reducing their risks. Similarly, domestic investment has an unexploited potential for promoting innovation. Moreover, besides making credit more accessible, the current unfriendly investment environment which is full of administrative, legal and market obstacles can be simplified.

Systemic Competitiveness Working Definition

Collaboration between actors is fundamental to ensure a successful structural change. According to the Systemic Competitiveness categorization, the meso level is the platform that provides the space to coordinate actions and strengthen the structures to support change.27 It is in the meso level where industrial policies and strategies to promote structural change take place. Structural reforms can create changes that directly impact the connectivity among the macro and micro levels of a national system. Therefore, the meso level concept is included in the assessment guidelines. The aim is to analyze by how far the reforms are promoting the creation or enhancement of structures at the meso level to support change.

Assessment Guidelines

Table 1 presents the previously described assessment strategies with their corresponding assessment criteria, which together make up the assessment guidelines that will be used in the upcoming section to analyze the structural reforms.

Source: Author's compilation based on: Esser et al., 1996; Gill & Kharas, 2015; Jankowska et al., 2012a; Kharas & Kohli, 2011; Lin & Treichel, 2012; Moreno-Brid, 2013; Ohno, 2009; Paus, 2012; Paus, 2014; Qureshi et al., 2014; Rodrik et al., 1995; Vivarelli, 2014

Mexico’s Recent Performance

In the last 50 years, Mexico, as most of Latin American countries, has undergone several policy changes which have shaped its economic evolution. Mexico is the 15th biggest economy and the 11th biggest market in the world28. Since 1994, it has developed a robust and stable macroeconomic environment. Among other indicators, inflation rates and interest rates have been declining and even reached historic lows.29 Its openness to trade has increased considerably and export levels have grown by almost 400 percent.

During the 2008 crisis, the country showed that it has a robust financial sector and macroeconomic management; which helped it mitigate the external shock. This positive performance has gained investor’s confidence and attracted global interest on the country. It is considered an emerging middle power and as one of the leading emerging economies in the world, is member of the G7+5 group. Nolte (2010), Scott, vom Hau, & Hulme (2010) highlight that international rating agencies have identified Mexico to have the potential of becoming one of the largest economies of the world in the following decades; making it part of the Next Eleven30 and MinT31 groups.

However, the Mexican economy is underperforming in many different areas that are highly correlated to the MiT. According to national poverty standards, 50 percent of the population was living below the poverty line in 2016.32 The Mexican industry has major challenges on productivity performance, which are hindering the country’s competitiveness versus economies with similar export baskets and lower costs like China. According to the World Economic Forum,33 the major opportunities for improvement are found in the quality of institutions, higher education and training, innovation factors and financial market development.

Moreover, the capacity of the state to finance the upgrading of the mentioned areas seems constrained by the low level of tax revenues. Mexico’s tax collection level has not made significant improvements in the past two decades and with 19.5 percent as a ratio of gdp34 is currently among the lowest in Latin America. This ratio includes oil revenues and contributions from state-owned enterprises. If these contributions are excluded from the total collection levels, the tax share drops to around 13 percent as ratio of gdp. Additionally, the informal sector employs almost 60 percent of the labor force and generates about 23 percent of the country’s gdp.35

According to Felipe, Abdon & Kumar,36 a country should take in average

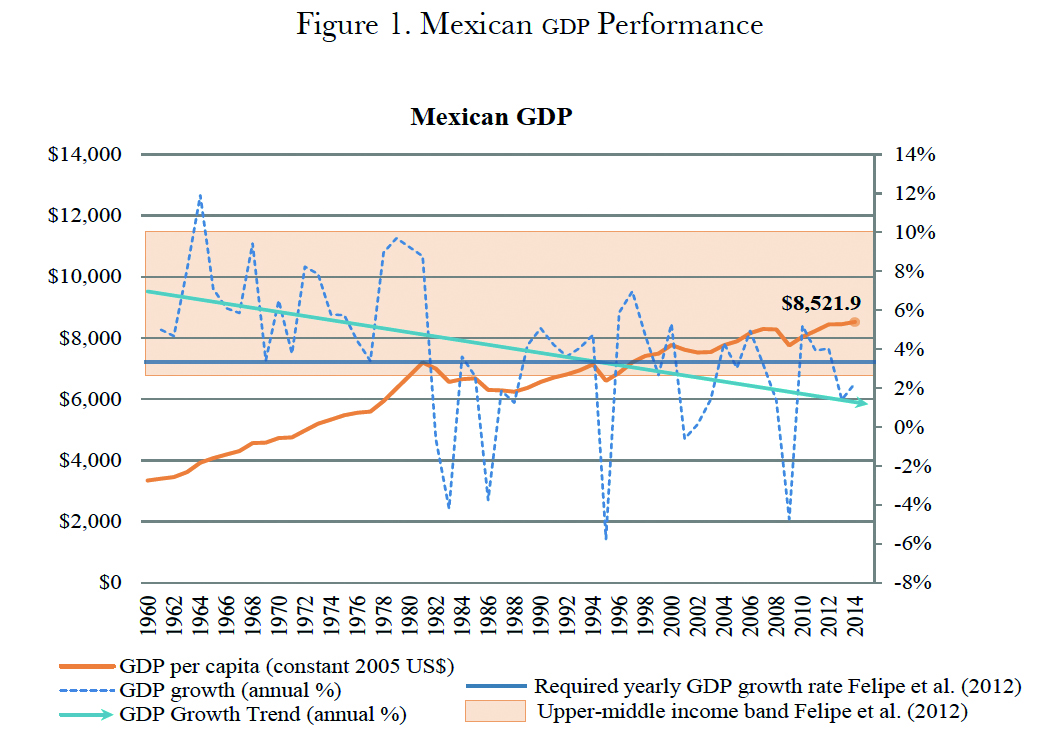

14 years as an upper-middle-income country with a 3.5 percent yearly growth rate to avoid falling into a MiT. Following these thresholds, Mexico has failed to avoid the trap. The current Mexican gdp per capita is $8,521 constant 2005 usd, with a yearly average growth rate of 2.6 percent since 1994.37 As Figure 1 shows, it has spent over 14 years as an upper-middle-income country, without reaching the recommended average growth rate.

The Origin of a Political Agreement

The unsatisfactory economic development of the country cannot be detached from the domestic political scene, which poses one of the greatest barriers for development. Mexico is characterized for having a divided political environment where agreements cannot be easily reached due to the unwillingness and opposing views of political parties; making it very hard to build stable coalitions to develop a long-term vision. The three dominating political parties are pri,38 which has been the historically dominating party in power; pan,39 which managed to be in power between 2000 and 2012, and prd,40 the leftist party which hasn’t managed to be in power yet.

In 2012, with the pri back into power a consensus was reached to prepare for the change of office. The existing gap between economic and human development indicators in addition to the growing competition posed by China and other developing economies were a clear call for collaboration. The leaders of the three dominating political parties, along with the elected president; Enrique Peña Nieto, worked on a political agreement called the “Pacto por México”.41

The “Pacto” is a document conformed by three core objectives in which five agreement areas were established and ninety-five specific compromises were defined with a specific timeline. The core objectives focus on strengthening the Mexican state; the democratization of economics and politics along with the application and widening of social rights, and promoting the citizens’ participation as fundamental actors on the design, execution and evaluation of public policies. The compromises that required changes to the Constitution were assembled under eleven structural reforms.42 One reform was approved under the president Calderon’s mandate before the change of office in 2012, and the remaining ten were approved along the first 20 months of Peña Nieto’s mandate.

The fiscal, financial and economic competition reforms are chosen for this analysis due to their potential impact on the economy and structural change of the country.

4. Structural Reforms Evaluation

In this section, the three selected structural reforms are evaluated according to the assessment guidelines previously established. For each reform an overview of its objectives, main scope of action and expected results will be presented. Afterwards, the expected results will be evaluated under the assessment guidelines to understand their capacity to boost growth. Additionally, a brief highlight of improvement opportunities and disregarded topics will be presented.

Economic Competitiveness Reform

The economic competitiveness reform incorporates nine out of the 95 compromises established in the “Pacto”. Effective since June 2013, this reform made changes and additions to eight articles of the Mexican Constitution that deal with monopolies and basic guidelines on economic activities. The main objective of this reform is to eliminate those market failures which impede a free competition among all actors and limit market efficiency. It aims to create a competitive environment by avoiding monopolistic dominance, anti-competitive behavior and by providing an adequate playing field for all actors; regardless of their size or time operating.

The main changes made by this reform are a) the creation of two autonomous and independent national agencies (Cofece and ifT)43 to monitor their assigned sectors and eliminate barriers to competition; b) the creation of a new Federal Law of Economic Competition44 which is aligned with the new functions and responsibilities of the two national agencies Cofece and ifT; c) specialized federal courts to manage competition disputes were established through a modification of the judiciary system.

The Government expects to develop solid dynamic markets with reduced entry barriers and higher efficiency. An improved competitive environment is expected to generate direct price reductions for consumers, increase the confidence among current and potential investors and improve innovation and productivity levels. A higher institutional strength is also expected from having independent agencies with increased accountability. A reduction of rent seeking incentives, political influence or interest groups’ influence is also expected.

Assessment

This reform can promote innovation in the country. The innovation assessment guideline is promoted by increasing market openness to new competitors and reducing market concentration. sMe and entrepreneurs can improve their competitive skills by using the assessment services and market evaluations offered by Cofece. These strategies comply with the assessment criteria 1.1 and 1.4. On its first year of operation, the agency identified seven industries45 where anti-competitive behaviors or the lack of competition reduce the purchasing power of households between 33 and 46 percent. Cofece proposed to prioritize these industries for investigation as they mainly affect the lower deciles of the population.

The meso level assessment guideline is complied with through the establishment of Cofece as an independent, reliable and transparent institution.46 Cofece can enhance the meso level capacity to support change. It is a platform designed to promote discussion among actors and efficient dispute resolution,

which also provides tools to self-identify anti-competitive practices. It is also designed as a collaboration space that gathers the opinion of researchers, universities, and enterprises with the aim to improve the competitiveness, institutions and legal framework as well as to promote fair competition on the markets. All these characteristics comply with the assessment criteria 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3.

The industrial policy assessment guideline is also promoted by this reform. The inclusion of an internal audit committee has the potential to increase the accountability of the bureaucracy and reduce conflicts of interest or capture by interest groups of the newly created agencies. The instauration of specialized courts should contribute to reduce the length of the legal conflict resolution procedures; diminishing transaction costs. In addition, Cofece has implemented a quantitative and qualitative process to measure the impact of both the existing competition problems and of the solutions it recommends. The previous changes and strategies promote the achievement of assessment criteria 2.4, 2.6 and 4.1.

It is important to consider that it has been only three years since its implementation, which is not enough to provide conclusive information for a final assessment. However, along these first years of operations Cofece has timely and clearly published monthly, quarterly and annual reports on its main objectives, obtained results and pending topics for the following period. Internal and external audits have been made to its financial operations and internal audit committee, enabling a transparent and easy access to information.

McKinsey & Company47 has made an analysis of the public perception regarding Cofece’s work and pertinence. This analysis proves that, overall, Cofece’s purpose and suitability are recognized by the public in general. It has also provided with opportunity areas to improve its public image and positioning, as well as its efficiency to meet its main objectives.

Cofece has developed a four-year strategic plan to prioritize its operations. It has established six priority industries48 to focus on the following four

years. Even though the reform incorporates the promotion of coordinated interactions among actors, government agencies and national levels; Cofece has not organized specific meetings with the different actors. It has created public consultations through its web site where any interested person can share his opinion on the topic and make recommendations.

The foundation of the Government’s expectations lies on the assumption that free markets on their own will induce innovation and increase productivity. The Government limits its role just to balance the playground and make sure regulations are in place to let markets self-equilibrate. This seems to be a strong assumption considering that there are other market failures which affect competition, and that sMe might need more than just fair rules to catch up in skills, technological use, innovation and competitiveness. This strong assumption seems to hinder the amount or quality of support that the Government’s authorities can provide to sMe and entrepreneurs on their catch-up process.

On the design of this reform, the Government assumed that anticompetitive practices are mainly related to economic competitiveness. It neglected other topics, which also affect fair competition in markets such as market failures related to public institutions’ inefficiency, the prevalence of foreign companies in domestic markets, the degree of business orientation towards consumers or even the sophistication degree of consumers.49 These factors can hinder the competitive skills of the businesses, mainly sMe limit the market openness or increase the transaction costs. Certainly, the reform is taking the first steps towards the correct direction. However, it should be kept in mind that competition is a continuous and changing process that requires that the Government’s institutions have the capacity to adapt and keep improving.

Fiscal Reform

Out of the 95 compromises established in the “Pacto”, eight are directly covered by the fiscal reform in addition to 40 compromises which depend on the reform’s approval for their implementation. Effective since January 2014, this reform made changes and additions to nine fiscal related federal laws, created one new income tax federal law and revoked two tax federal laws.

Overall, this reform aims to increase the State’s responsibility on the public finance management, increase the fiscal collection levels, make the tax system more progressive, simplify the tax payment process, promote the local tax collection of states and municipalities, improve the transparency and efficiency of spending as well as improve the social security nets. The main changes made by this reform can be categorized in 6 groups.

Taxes: this category had the largest amount of modifications and additions. Changes were made on vaT, personal and corporate income tax and tax incentives. Specific fiscal regimes were updated or removed. A new fiscal incorporation regime for sMe and entrepreneurs was created. Additionally, a 10 percent tax on capital gains was established for corporations and individuals and three additional income bands were included.

Tax collection: the tax collection process was upgraded, requiring the use of electronic tools and documentation, the sanction scheme was updated to cover for offenses from taxpayers, tax advisers and to typify new crimes. The reform introduced new strategies to correct omissions or errors and reach debt agreements.

Customs: the legal framework was updated to require the usage of electronic documentation and transactions; additionally, the sanctions scheme was updated. The approved places for merchandise clearance were also broadened.

Budget and fiscal responsibility: the structural balance rule was updated to allow counter-cyclical measures and the size of the state’s and municipalities’ share over their total tax collection was increased.

Transparency and accountability: the legal framework were updated; taxing authorities must provide open access to information. Likewise, a tighter control over budget spending was included

Social security nets: the implementation of unemployment insurance along with a universal pension for the elderly was promoted. This section of the reform was presented as a separate law proposal, and as of March 2016, was still pending approval from the Senate.

As a result of this reform, the Government expected to increase the tax collection level by one percentage point (as gdp ratio) in 2014 and it estimated that by the end of 2018 the tax collection would grow by 2.5 percentage points (as gdp ratio). With the higher budget availability, the government expects to increase its expenditure levels on education, health, infrastructure and social programs. Furthermore, it also anticipates a reduction on tax evasion due to the strengthening of the tax system controls.

Assessment

The reform can improve the Government’s control over the benefits offered to specific sectors; it has the potential to increase the financial availability and simplify the tax collection system; promoting the financial availability assessment guideline. Additionally, it can strengthen the meso level by improving the fiscal structures and enhance their efficiency through the adaptation of up-to-date technology and electronic platforms, promoting the meso level assessment guideline.

The expansion of tax incentives to industries and sMe appears to increase the support given for the development of the industrial sector. The attempts to simplify and improve the efficiency of the tax collection and customs systems have the potential to reduce the transaction and administration costs for businesses and individuals; allowing the achievement of the assessment criteria 2.2, 3.1 and 3.2. Even though the Government does not consider tax incentives and tax breaks as a type of direct industrial policy, these tools can be an adequate first approach to support the industrial development of the country.

The changes on taxes can mainly contribute to increase the tax collection levels, improve the collection system and its control. The strengthening of the fiscal institutions and the migration of the processes to an electronic platform can increase the control and reduce their transaction costs. The updated sanction schemes, along with an adequate monitoring system, can contribute to reduce the offenses from taxpayers and tax advisers. Finally, giving incentives to the states and municipalities to increase their tax collection can promote a higher level of collaboration between national levels. All these changes are aligned with the assessment criteria 3.1, 3.2, 3.3 and 4.2.

Even though the reform aims to increase the tax collection level 2.5 percentage points by 2018, Mexico’s tax revenue levels will still be below the oecd’s average. The addition of income bands to the personal income tax seems to be heading in the right direction to reduce inequality. Nonetheless, the corporate income tax structure and rate still represent an opportunity to make the tax system more progressive.

Additional opportunity areas lie within the internal controls structure and the tax incentives. Although the financial authorities already have an audit committee and internal control systems in place, further external audits to test their operation and effectiveness50 might be useful to increase their robustness. Finally, tax incentives could be extended beyond the primary sector to also support specific industrial activities that foster technological upgrading and industrialization.

The fiscal reform also excludes some topics from its scope, which could provide better alternatives or create stronger dynamics to boost growth. First, the reform takes a weak approach to revamp the tax system; it does change the tax rates but misses to make changes on the system arrangements. Secondly, the reform lacks strategies to broaden the tax base by either narrowing the informal sector or establishing alternative revenue sources. Something more than a fiscal incorporation regime is needed to successfully broaden the formal sector. Strategies to identify and sanction those taxpayers that still make certain operations in the informal sector are missing. Additional incentives to attract enterprises and workers to the formal sector need to be explored too.

In addition, little weight is given to the establishment of alternative and additional sources of fiscal revenue. This can be achieved by either increasing the existing rates or establishing new excise taxes. Taxes on gambling, luxury items, concerts or property ownership and their progressiveness might represent potential additional income. These alternative revenue sources can avoid increasing the distribution inequality or affecting the low and middle-income class.

Financial Reform

Effective since January 2014, the financial reform includes three out of the 95 compromises established in the “Pacto”. The main objectives of the reform are to maintain a sound financial system and increase the competition within it, improve credit access and supply through public and private financial institutions; and additionally, to make the financial authorities and institutions more efficient and accountable. This reform made changes and amendments to 34 finance related laws. The predominant changes are related to the legal framework, scope, sanction schemes and corporate governance.

The reform impacts three main parts of the financial sector. The financial institutions (public and private) are allowed to expand their coverage of markets, products, operations, and authorized partners. Changes on the legal framework expand and make their faculties more specific and broaden the sanction schemes. They are required to establish an audit committee and to execute periodic assessments from independent external auditors. The update of the legal framework enables financial authorities to apply prudential measures, implement additional capital requirements, and establish corrective measures. It also requires the authorities to estimate and provide statistical information of the market and participating institutions. Finally, there are financial processes: the changes of their legal framework cover insolvency criteria and update civil responsibility, and sanction schemes. The legal framework was also updated to include the migration to electronic platforms. Finally, the judicial process was updated to establish specialized courts for financial matters and update the faculties and cases allowed for property seizure.

As a result, the Government expects that this reform unlocks the potential of credit as a tool for economic development and promotes a more inclusive development. It also expects to make a more robust financial system through increased regulation, control and coordination among financial institutions and authorities.

Assessment

Overall, the financial reform seems to have the adequate features to deepen the financial system and help Mexico get out of the MiT. It can make improvements on the four established assessment guidelines. The reform can increase the competitiveness of the financial institutions and the competence of financial authorities to regulate the markets and ensure free competition, promoting the innovation assessment guideline. It has the potential to broaden the access to credit and support the industrial development of the country, benefiting the industrial policy and financial availability assessment guidelines. Additionally, it can strengthen the meso level by consolidating the control systems of financial institutions, improving the faculties and supervision competences of the financial authorities and making the financial processes more efficient, directly promoting the meso level assessment guideline.

The broadening of the authorized operations, products and partners for financial institutions can expand financial markets and increase the competition within them. The expansion of markets may broaden the types of customers targeted by financial institutions; benefitting sMe and population that currently do not use financial services. In addition, it may provide customers with an easier access to financing opportunities for technological and skills upgrades. The establishment of internal control systems, clear responsibilities for board members along with an update of the sanction schemes can strengthen the institutions’ structure. These strategies promote the achievement of the assessment criteria 1.1, 1.2, 1.4, 2.3, 3.4, 3.5 and 4.3.

The update of the legal framework for the financial authorities has a good potential to increase the competition on financial markets, reduce risks and transaction costs. This improvement can also promote the diversification of credit provision to support specific sectors. The additional faculties and judicial attributions provided may support an institutional strengthening and promote the coordination and collaboration among actors.

In addition, the improved regulation on the financial processes can lead to efficient and adequate sanctions enforcement. It may also increase market competitiveness, drive a steady compliance of the standards by the financial institutions, and create a more reliable financial system. Furthermore, the adequate monitoring can significantly reduce principal-agent risks within financial institutions and authorities. The previously mentioned changes also support the assessment criteria 1.1, 1.2, 2.6, 4.1 and 4.3.

Despite the extensive changes made by the financial reform, there are still some topics which seem to require further development. It seems that the Government is assuming, that an increase of credit will directly promote innovation and industrial development. However, it is important to consider that for this assumption to be true, the credits provided need to be directed to activities and investments that lead to an upgrade of the productive sectors and their value added. Hence, it is important to design adequate incentives and processes, which drive credits to productive objectives and deviate them from consumption purposes.

Likewise, there are some aspects related to credit provision that seem to have been disregarded. First, the reform is not clear on the specific incentives or strategies to be implemented to make sure that credit levels increase and diversify their beneficiaries. Secondly, it misses to consider the potential impacts on credit provision that the fiscal reform might create. The fiscal reform eliminated the tax deduction of preventive global reserves for financial institutions, which could lead to a reduction on credit supply.

Another topic that seems to be neglected, is related to counter-cyclical measures authorizations. The financial reform provides the financial authorities the faculty to increase the amount of capital requirements to specific institutions. Yet, it does not give them any faculty to lower, in a limited extent, the capital requirements for robust financial institutions as a counter-cyclical measure.

Finally, the financial reform excludes from its scope the promotion of savings. As it is important to boost investments to boost growth, it is also important to encourage savings. The reform fails to devise strategies to drive the profits from the credits provided away from consumption and back to the financial system. Inclusive strategies to promote a savings culture among the population represent an opportunity area with significant potential.

There appears to be a general weakness on the action-oriented participation of the Government. The three structural reforms mention as a goal the development of the strategic sectors of the country. The national development plan is the document that guides all policies and ministries of the government towards general goals. This plan establishes the priorities, objectives, and main lines of action for the different government areas. However, it is not specific enough on the selected industrial strategic sectors. This lack of detail can reduce the effectiveness of policies or strategies to boost development and create structural change to upgrade the economic structure.

5. Conclusions & Policy Recommendations

According to this paper’s working definition, Mexico is stuck in the MiT and in need of structural reforms to escape from it. In general terms, the assessed structural reforms are aligned with the MiT recommendations and seem to have the capacity to boost growth. Overall, they intend to improve market competitiveness, lower transaction costs, make their related processes and institutions more efficient, improve credit access, as well as to enhance the institutional structures to support change. However, the success of their implementation is highly dependent on the adequate monitoring by the authorities and on the compliance with the changes of all the actors involved.

It is important to consider that the reforms covered have been recently implemented. In general, with more data available, further research is recommended on the three reforms to assess the efficiency and robustness of the established audit committees on the institutions.51

For the economic competitiveness reform, an analysis of the intervention of Cofece on the identified priority markets5252 and a measurement of the competitiveness improvement within them is suggested. For the fiscal reform, an assessment of its long-term effects to narrow the informal sector and reduce inequality is advised. Finally, for the financial reform, an evaluation of the credit provision of development banks is recommended, especially to identify if they channeled credit to new industries, which can become the new comparative advantages of the country.

Some opportunity areas can already be identified to improve their approach and potential impacts. The competitiveness reform seems to be built on the assumption that free markets will incentivize innovation and increase productivity. However, sMe might need a more active government to support their catch-up process. The fiscal reform misses to define clear strategies to broaden the tax base by either narrowing the informal sector or by establishing alternative revenue sources.

The financial reform seems to be built on the assumption that an increase on credit will directly promote innovation and industrial development. However, it is important to design adequate incentives and processes which drive credits to productive objectives and deviate them from consumption purposes. At the central government level there is lack of clearness on which industries comprise the strategic sectors mentioned in the structural reforms.

To complement the current efforts and changes made by the structural reforms a couple of additional policies could help. A more proactive government can drive an effective industrial and capabilities upgrade in collaboration with the private sector. A set of strategic industrial sectors clearly defined can drive efforts towards the same direction and ease collaboration among actors to promote structural change. One first attempt of the government to promote the industry development has been the creation of special economic zones in the country. Nonetheless, there is still missing a specific identification of the country’s strategic industrial sectors.

Industrial policy targeted to the specialization of domestic businesses and to support sMe, entrepreneurs and start-ups can contribute to consolidate the economic structure upgrade. The promotion of public-private investments in infrastructure can mitigate the risks perceived by investors, ease the industrial interconnections and increase the efficiency of businesses.

Broadening the tax base is fundamental to provide the financial resources that will support the implementation of strategies. Narrowing the informal sector or finding additional revenue sources can contribute to broaden the tax base. Finally, inclusive strategies to promote a savings culture among the population represent an opportunity area with significant potential to increase the financial lending pool.

In conclusion, the structural reforms undertaken by the Mexican government are moving towards the correct direction to boost growth. They symbolize the recognition of the limited development advancements of the country across the previous years. Nonetheless, it seems that the Government takes a modest approach to tackle the MiT. While the data is complex and has many variables, a more proactive government participation in the economy has the potential to create more benefits, to upgrade the economic structure and promote a stronger platform to link reforms, actors and government institutions for a successful structural change.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)