Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.16 no.2 Texcoco abr./jun. 2019 Epub 25-Feb-2020

https://doi.org/10.22231/asyd.v16i2.1009

Articles

Transference and political cohesion of dissident governments in Mexico

1Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla. (alfonso.mendoza@upaep.mx), (miguel.cruz@upaep.mx)

The integration hypothesis proposes that transferences can be used as instruments of adhesion, rather than as incentives to reinforce fiscal autonomy. In this study, we test this hypothesis by examining the differential amounts of transferences allotted to municipalities ruled by uses and customs and to municipalities ruled by political parties, using information from the 570 municipalities of the state of Oaxaca. We established the dynamic impact of participations and contributions on the fiscal effort of the two types of municipalities through Autoregressive Vectors (ARV) and we distinguish the dynamism of fiscal variables and the common factors in both types of municipalities. We find that the municipalities with uses and customs have received higher federal transferences per capita; that participations exert a positive and persistent impact on the municipality’s own tax collection; that contributions have a negative and persistent impact of the municipality’s own tax collection; that contributions impact negatively the participations; and that participations impact positively the contributions.

Key words: fiscal autonomy; fiscal federalism; uses and customs

La hipótesis de integración establece que las transferencias pueden utilizarse como instrumentos de adhesión, más que como incentivos para reforzar la autonomía fiscal. En la presente investigación sometemos a prueba esta hipótesis examinando los montos diferenciales de transferencias asignados a municipios regidos por usos y costumbres y a municipios regidos por partidos políticos, utilizando información de los 570 municipios del Estado de Oaxaca. Determinamos el impacto dinámico de las participaciones y las aportaciones sobre el esfuerzo fiscal de los dos tipos de municipios mediante Vectores Autorregresivos (VAR) y distinguimos el dinamismo de las variables fiscales y los factores comunes en ambos tipos de municipios. Encontramos que los municipios de usos y costumbres han recibido mayores transferencias federales per cápita; que las participaciones ejercen un impacto positivo y persistente sobre la recaudación propia del municipio; que las aportaciones tienen un impacto negativo y persistente sobre la recaudación propia; que las aportaciones impactan negativamente a las participaciones, y que las participaciones impactan positivamente a las aportaciones.

Palabras clave: autonomía fiscal; federalismo fiscal; usos y costumbres

INTRODUCTION

The study of the fiscal interrelation between the federation and the local political forces can be generally addressed from two approaches: from the normative approach, centered on the economic rationality of the transferences (Boadway and Hobson 1993), and from the positive approach, which explains decentralization as a result of the local political-democratic struggle (Johansson, 2003).

In the normative approach, decentralization is considered to be a promotion mechanism for fiscal competition between local governments. As such, transferences are incentives that may correct, but may also accentuate the defects of this struggle. The positive approach, instead, deals with decentralization as a result of the interaction between the agents interested (stakeholders) in the local government (Sato, 2007). The patterns of behavior, the style and amount of transferences, as well as the fiscal effort and autonomy of local governments are the result of the institutional structure created by the agents.

The approach of positive political economy is very attractive, since it allows explaining some relevant characteristics of inter-regional relations and of transferences, such as the political influence of specific social groups (rent seeking), as well as their capacity to attract federal resources (Inman and Rubinfeld, 1996). It also integrates the study of problems of agency, where organized groups with greater political influence can gain access to more funds (Dixit et al., 1997).

Some authors have also examined the possibility that political struggles of the regions give place to an asymmetrical federal treatment. With the aim of ensuring the stability and cooperation of the regions, federal transferences can be used by the central government as adhesion mechanisms, rather than as incentives to the fiscal effort of local governments (Inman and Rubinfeld, 1997). Bolton and Roland (1997) have reported, for example, that municipalities with social discontentment receive more transferences, while Leite-Monteiro and Sato (2003) find that transferences are used as investment spending to maintain the unity of the regions.

Studies about asymmetrical federalism and the use of transferences as instruments of regional and social cohesion are scarce for developing countries. There are not enough studies about the impact of differentiated fiscal treatment on the tax collecting effort of the regions in the world or in Latin America. In this article we seek to cover these spaces in the literature by exploring, first, the evidence on asymmetric federalism: whether federal transferences to dissident municipalities show levels and dynamics different from the municipalities within the political norm. Second, we examine the possibility of federal transferences stimulating the tax collecting effort of local governments, as well as the intensity and the substitution among transferences by type of political regime.

In order to do this, we use information about the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca in Mexico, one of the few federal entities in Mexico where we can make a clear distinction between municipalities inserted in the democratic normalcy of the country and those in alternative political systems like the so called uses and customs (U&C), which we identify in this study as municipalities in discontentment with partisan normalcy. A higher and more persistent amount of transferences towards municipalities in discontentment, in addition to a low tax collection effort provide evidence of asymmetric federalism, directed at maintaining the stability and political-social cohesion, rather than stimulating the fiscal autonomy of local governments.

Given the still inconclusive evidence regarding the impact of federal transferences on the fiscal effort of municipalities in Mexico, in this study we also contribute to the literature by examining the dynamic causality and the persistence of federal transferences on municipal tax collection using a model of Autoregressive Vectors (ARV) for the panel data, through the Generalized Moments Method (GMM). According to our literature review, this is the first study that measures the dynamic influence of these factors on local governments shaped under the regime of uses and customs.

ECONOMIC POLICY OF THE TRANSFERENCES: BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW

In this article we follow the positive approach of the economic policy models that suggest that the design of transferences and the autonomy of municipalities are determined by the political struggle between the agents interested (stakeholders) of local governments (Sato, 2007). We identify in this study three theories that explain the transferences as a result of the political struggle between the agents: machine politics, swing voters, and political integration.

The first approach, the theory of machine politics suggests that the transferences are directed mostly in favor of groups of political support at the expense of dissident or adversary groups (Dixit and Londregan, 1996). The greater the political capital and the hard vote of this group are in favor of the federation, the higher the amount of the transferences will be (Porto and Sanguinetti, 2001). The second approach (swing voters) points out that the competition over indecisive votes can also define the relationship between the federation and local governments. Some authors have found that groups with less political adhesion, with more swing votes, as well as those with lower income tend to receive more transferences than those inserted in the partisan competition (Boadway, 2002 Dixit & Londregan, 1998). The third approach examines the relationship between the federation and local governments in a context of political integration. In this current it is considered that a central government can use the transferences to keep a region united in face of separatist movements. Thus, higher transferences would be destined to dissident municipalities to maintain stability and political cohesion (Sato, 2007).

In this third approach, the transferences can be used as mechanisms of political integration, that is, to ensure cooperation, rather than being used as incentives for local governments (Inman and Rubinfeld, 1997). Sato (2007) highlights that a type of asymmetric federalism can be generated, where some municipalities with higher political power and separatist desires receive higher transference amounts. This pattern can be more evident in regions that are culturally, religiously and linguistically heterogeneous.

In this sense, the transferences maintain national unity by ensuring that the welfare of these municipalities is higher within the federal pact than outside of it (Sato, 2007). The separatist possibility of the regions distorts the fiscal policy of the transferences in favor of the municipalities in discontentment (Bolton and Roland 1997). Leite-Monteiro and Sato (2003) have found that in a globalized environment, fiscal regimes emanating from inter-regional negotiation, which in turn use transferences as additional payments to maintain the unity of the nation, are preferable to centralized regimes.

Becker (1983) had also contemplated the possibility that the transferences to small regions would be relatively higher, since as a whole some groups can exert greater pressure and in sum show a higher lobbying capacity, not only with the legislative branches, but also with the executive power itself. In addition, framed within a problem of agency, Dixit et al. (1997) note that organized groups with higher political influence have more access to federal funds than unorganized groups. Brock and Owings (2003) and Grossman (1994) find that the amount of transferences per capita is positively correlated to the proximity, not just geographic but also political, of the groups.

Organizational theory also points to the possibility of the emergence of the hold-up problem, in which municipalities can show low tax collection if they perceive that a greater fiscal effort is associated to lower future transferences. Not only are negative effects generated on the incentives of future collection, but also mistrust between local governments and the central authority (Zhuravskaya, 2000).

In addition, local governments could receive the transferences as instruments of control, which is why they can represent a cost in terms of the loss of autonomy (Alesina and Spolaore, 1997; Bolton and Roland, 1997). Those municipalities that seek to maintain or consolidate their autonomy, increasing their political strength as a group, could also be renouncing to the adoption of the criteria and the logic of federal fiscal distribution.

This study has several objectives. In principle, it explores the evidence in favor of asymmetric federalism (Sato, 2007); whether the municipalities chosen democratically are more efficient in their own tax collection (Wittman, 1995); whether the municipalities in partisan competition face lower costs for relative collection (Alesina and Spolaore 1997; Bolton and Roland, 1997); and whether higher collection of their own is related with drops in the amounts of transferences [within the logic of ex post financial rescue to avoid political instability (Zhuravskaya, 2000)].

Fiscal effort and transferences in Mexico

One of the objectives of the current federalist pact in Mexico is to stimulate the fiscal effort of municipalities, which is why it would be expected that higher income would be associated with higher amounts of unconditioned transferences (participations), Cárdenas and Sharma (2011). However, the evidence still has not reached consensus. For example, analyzing the impact of federal help on spending by local governments, Benton (1992) found that their own income dropped with the federal backing, regardless of the relative amount. In turn, Bell and Bowman (1987) and Stine (1994) did not find a significant effect of the state help on the autonomy of local governments. Peña and Wence (2011) mention the importance of the design of transferences to foster tax collection in the municipalities.

When analyzing the existence of the fly swatter paper effect in the states of Mexico for the period of 1993-2002, Guadarrama (2006) reported that the increase of federal transferences reduced the fiscal effort of the federal entities. Moreno (2003) reports in turn an increase of the tax collecting effort to higher unconditioned transferences (participations), but lower collection as response to higher conditioned transferences (contributions), result that is shared by Unda and Moreno (2015). In their turn, Sobel and Crowley (2014) find that the federal transferences toward the states increase the tax collecting income (and their own taxes).

Instead, Sour (2004, 2008) finds negative impacts of the transferences on fiscal autonomy. Sour (2008) uses panel data from 155 urban municipalities for the period of 1993 to 2004. In both studies, the author finds that the transferences exert a negative stimulus on the municipality’s tax collection, since the local governments prefer to receive the transferences than to face the political and administrative costs that result from their own tax collection.

Other studies have focused on measuring the impact of fiscal autonomy on the transferences, also with mixed conclusions. For example, using cross-sectional data from the year 2004 for the 31 federal entities of the country, Cabrera and Lozano (2011) report a significant impact of the degree of autonomy (measured by the participation of own income from total income) on the Federal Participations (Branch 28) and the degree of financial autonomy (measured as the percentage of own income divided by the total income); they also find a negative impact that is statistically significant of the degree of financial autonomy on the Federal Contributions (Branch 33).

Other empirical studies, such as that by Ibarra, Sandoval and Sotres (1999), find that both the Fiscal Coordination System of 1980 (Sistema de Coordinación Fiscal, SNCF) and the Constitutional Reform of Article 115 in 1983 reinforced the dependency of municipal public finance agencies on participations. These authors found evidence that the percentage that represented the participations in the average of municipal incomes was significantly higher in the periods of 1980-89 and 1990-95, compared to the period of 1975-79 (prior to the enforcement of the SNCF and the Constitutional Reform). Likewise, they found that both the SNCF of 1980 and the Constitutional Reform of Article 115 in 1983 have had a negative impact on the Fiscal Autonomy of the municipalities. The increased dependency of municipal public finance agencies regarding the federal transferences has also been documented in the study by Isusquiza (2014) for the case of Mexico and by Bello and Espitia (2011) for the case of Colombia.

Fiscal autonomy and political configuration in Mexico

The relationship between political competition and fiscal effort in Mexico has been studied by Ibarra and González (2009), who analyze the effects of the political environment on financial autonomy1. Among other results the authors find that the political affiliation of the municipal president impacts the financial autonomy depending on the political party in power2. They also find that financial autonomy is conditioned positively by the political confluence between the municipal president and the governor, while the political confluence of the municipal president and the congress does not seem relevant.

Ruiz Porras and García-Vázquez (2013) study for their part the relationship between the dynamics of the per capita transferences and the partisan origin of the municipalities in the state of Jalisco for the period of 2005-2011. The authors report that between 2005 and 2009, the transferences toward municipalities of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) (ruling party in most of the municipalities), are higher than those in the municipalities of Partido Acción Nacional (PAN). In 2010 this situation reverts in favor of PAN and the municipalities where other parties rule receive less transferences. Likewise, Ruiz Porras and García-Vázquez (2014) analyze the economic and political criteria in inter-government transferences and find that during the period of 2005-2011 they increased for the municipalities ruled by PAN, PRI and other parties in 41.1, 26.2 and 34.9%, with the PAN municipalities being the ones that obtained higher increases in this period, when coincidentally this party controlled the Presidency of the Republic and the Governorship of the State, suggesting that there really was a political criterion in the allotment of transferences toward the municipalities.

Díaz Cayeros (2004) showed that the percentage of votes received by the PRI in the 31 federal entities in 1998 was correlated positively and significantly with the distribution of the Contributions, but not with the Participations.

Ibarra and Sotres (2009) explain property tax collection as a function of political variables representing the government period of the political party of the municipal president in turn. The authors find an indefinite, non-significant relationship between property tax collection and the period of municipal government, and a negative but non-significant relationship between property tax collection and the political affiliation of the municipal president. However, Ibarra (2011) finds a non-significant relationship between property tax collection and the government period when the governor and the President of the Republic belong to the same party, although when the governor and the congress belong to the same party there is lower financial independence when it is PRI and higher financial independence when it is other parties.

Nevertheless, in our literature review for Mexico we do not find references that associate the fiscal effort of the municipalities with the political origin of the local governments, in particular differentiating if they emanate from the partisan struggle or from other processes such as uses and customs in the state of Oaxaca.

Oaxaca: the study case

With the aim of examining whether the style of political and democratic struggle of the local governments shapes the levels and the dynamics of transferences from the federation toward the municipalities, in this article we use a sample with municipalities emanated from partisan political processes and from uses and customs. This sample of municipalities allows examining the hypothesis suggested in the prior section: machine politics, swing voters and political integration.

Oaxaca is one of the three federal entities where local governments may be chosen using the scheme of uses and customs, an alternative constitutional political origin to the system based on political parties3. This differentiated political-cultural origin also allows assuming that the style of government can respond to criteria of their own, not necessarily aligned to the federalist pact.

There are also reasons of sociocultural nature that might suggest that the fiscal relationship in municipalities ruled by uses and customs is different from the municipalities chosen by parties. Among other authors, Labastida et al. (2009) points out that the system of uses and customs constitutes a primary source of social cohesion, much stronger than the one emanated from other state institutions. In these municipalities, the priorities of public spending can be different in terms of education, for example, and the fiscal contribution can be given through work in favor of the collective benefit (Tequio). In these municipalities with indigenous identity and culture of their own, a general negative perception by the population toward political parties is also reported, which compete in practice with hierarchical-religious structures.

The uprising of the indigenous population in the state of Chiapas in the year 1994 lit spotlights, not just in this federal entity, but in the whole southern region of the country including Oaxaca. Some authors identify the Zapatista uprising as the direct antecedent that motivated the elevation to constitutional range of the Uses and Customs regime. In fact, both the Law of Elections by Uses and Customs of 1995, the San Andrés Larrainzar Agreements of 1996, the reforms to the secondary Laws in the Constitution and the Law in Matters of Indigenous Rights and Culture of 2001, all gave political autonomy and legality to these municipalities.

Some authors point out that, in addition to the strong intervention of the police and the army in the search of cells of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), the legalization of uses and customs in Oaxaca stopped the emergence of armed movements in 1995 (Owalabi, 2004). Other authors note that in Oaxaca, however, the municipalities of uses and customs have maintained their position of resistance to preserve their customs, language and lands, even long before the appearance of Zapatistas in Chiapas (Mendoza, 2009).This process of integration and political recognition as a group seems to have buffered the political and social discontentment in later years, but it could also have generated a federalist asymmetry between the municipalities chosen by uses and customs and those chosen in partisan struggles by giving them higher amounts of federal transferences4. And, however, little or nothing has been studied about this theme or the impact of this political-social shock on the fiscal autonomy of the municipalities. The impact on the municipal relationships with the federation and the effect on the fiscal incentives of these municipalities compared to the municipalities chosen by political parties are also unknown. In the next sections we take up again, in particular, the case of Oaxaca to test the hypothesis of asymmetrical fiscal federalism.

ARV WITH PANEL DATA

The methodology of the panel data is the appropriate estimation approach for samples where there is a set of economic units (municipalities) that evolve in time. However, the methodology of standard panel data does not exploit completely the dynamic interrelation and the response of variables in face of shocks. For this reason, in this study we extend the methodology of Autoregressive Vectors (ARV) to panel type data, which allows analyzing the interrelations of the variables and their effects on the temporal and transversal dimensions. At the same time, the methodology allows capturing the heterogeneity that is not observed in the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca, as well as measuring individual and joint temporal characteristics of the variables under study.

The ARV with panel type data to be used for the study of municipal autonomy and the impact of the transferences are specified in the following manner:

where the vector of endogenous variables z i,t-j includes three variables: municipal tax collection, amount of contributions, and federal participations for each municipality i and for each lag t-j with j=[0,...,k]. The marginal impacts g ij are contained in G j for each lag j >=1. With the aim of measuring the individual heterogeneity of the municipalities, f i is included, and d t is included to capture the temporal heterogeneity.

In this specification, the fixed effects are correlated with the explicative variables and particularly with their lags z i,t-j . The violation to the assumption of independence is usually corrected differentiated; however, in the case of ARV with panel data, this differentiation would induce bias in the parameters estimated. To avoid this problem and ensure the orthogonality between the fixed effects and the lags of the variables, in our econometric exercise we use advanced differentiation compared to the mean, known as the Helmert, de Arellano and Bover procedure (1995) 5.

The extension of the ARV model with panel data that we propose here considers in addition the possibility of the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca being affected in a common way in specific points in time. This possibility is measured by d t approaching the impact of macro regional economic effects shared by all the municipalities that are not included in z i,t or any of their lags. In this case, the fixed effect is eliminated applying deviations of each variable compared to the mean for each municipality and year respectively.

According to other panel studies, for the exam of municipal public finances from the state of Oaxaca we build a base with few annual data but with ample number of municipalities (570) -the highest number in the whole Mexican Republic-which ensures a consistent estimation of the parameters. The model specified in (1) also includes the following assumptions: E(e i,t )=0 and E(e i ,e’ i,t )=W i . The ARV with panel data is estimated by using the Generalized Moments Method (GMM) and the routine developed by Inessa Love6,7.

One of the advantages of the analysis of Autoregressive Vectors is the possibility of examining the Functions of Impulse Response (FIR) and the variance analysis, which the standard methodology of panel data does not allow doing. The ARV with panel data used in this study allows us to perform this type of exam and even to calculate standard errors through Monte Carlo simulations with 5 % and 95 % bands. The identification of the model uses the Choleski decomposition.

EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS OF THE DATA AND RESULTS

The data used in this study utilize statistics provided by the Ministry of Finances of the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca. The consistency of all the data and the comparability with the public information available reported by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI) and the Ministry of Finance (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, SHCP) was verified. The state of Oaxaca has 570 municipalities from which we obtained information about contributions, participations and income of their own (property and water taxes) at current prices for the period 2002-2010. With these data a balanced panel was formed that contains in total 5,130 observations. The nominal variables were deflated with the National Consumer Price Index (Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor, INPC) and per capita values were calculated at constant prices of the year 2010. The municipal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was calculated following the methodology by Sánchez Almanza (2000) and Unikel (1976), also used by Ibarra and Sotres (2009) in the municipalities of the state of Tamaulipas.

The municipalities are also typified according to the political regime that they follow, that is, whether they are ruled by the principle of ‘uses and customs’. This is the first time that a study distinguishes this characteristic in the exam of the association between fiscal effort and federal transferences in Mexico.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables under study in per capita values, distinguishing the political origin of the local governments. In particular, it is observed that the larger part of the municipalities follow a regime of uses and customs (418 of 570). The municipalities ruled by uses and customs (U&C) collect in average much less fewer resources per inhabitant than municipalities chosen by parties. It is evident that these averages undervalue the behavior of the income if we consider the magnitude of the standard deviation, which actually suggests that there are some municipalities with much higher tax collection levels-among them the capital of the state (Oaxaca de Juárez), followed by Santa María Huatulco, San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec and Salina Cruz, among others. Such dispersion of the data also confirms the marked inequality of municipal income in the state of Oaxaca. While there are a very high proportion of municipalities that do not collect a single Peso (MXN), such as Santa María Texcaltitlán, Santiago Texcaltitlán, Santiago Atitlán, among many others, there are others that achieve an average collection of up to MXN $ 88 million pesos (levels at 2010 prices).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of fiscal variables in municipalities ruled by uses and customs, and by political parties.

| Municipios | µa | Xb | σc | Mín.d | Máx.e | Sf | Kg | Nh | ρi i |

| Grupo A: Municipios con régimen de Usos y Costumbres (n=418). Valores per cápita.j | |||||||||

| Recaudación Propia | 37* | 18 | 56 | 0 | 1008 | 5 | 52 | 3764 | 1.00 |

| Participaciones | 1437* | 1039 | 1228 | 248 | 12 865 | 3 | 19 | 3764 | 0.50 |

| Aportaciones | 1450* | 1371 | 490 | 405 | 4551 | 1 | 6 | 3764 | -0.40 |

| Grupo B: Municipios rlegidos por Partidos (n=152). Valores per cápita. | |||||||||

| Autonomía fiscal | 54 | 26 | 107 | 0 | 1348 | 7 | 76 | 1366 | 1.00 |

| Participaciones | 800 | 631 | 576 | 237 | 5995 | 4 | 27 | 1366 | 0.26 |

| Aportaciones | 1199 | 1126 | 395 | 451 | 5844 | 2 | 18 | 1366 | -0.51 |

| Grupo A: Municipios con régimen de Usos y Costumbres (n=418). Valores en Niveles.k | |||||||||

| Autonomía fiscalj | 114* | 31 | 786 | 0 | 18 500 | 18 | 353 | 3764 | 1.00 |

| Participaciones | 2509* | 2036 | 2010 | 557 | 34 900 | 8 | 103 | 3764 | 0.30 |

| Aportaciones | 4602* | 2587 | 6096 | 104 | 58 300 | 4 | 21 | 3764 | 0.11 |

| Grupo B: Municipios con elegidos por Partidos (n=152). Valores en Niveles. | |||||||||

| Autonomía fiscal | 1731 | 131 | 7156 | 0 | 88 000 | 8 | 74 | 1366 | 1.00 |

| Participaciones | 10 400 | 4074 | 30 400 | 770 | 457 000 | 10 | 111 | 1366 | 0.80 |

| Aportaciones | 15 300 | 7770 | 21 800 | 471 | 203 000 | 4 | 27 | 1366 | 0.64 |

Source: author’s calculations based on data provided by the Ministry of Finance of the state of Oaxaca. a µ: Arithmetic average of own income (property and water taxes); b X: median; c σ: standard deviation; d Mín: Minimum; e Máx: Maximum; f S: Bias; g K: Kurtosis; h N: number of observations, made up of n municipalities and T time; i ρ: correlation coefficient between fiscal effort and each one of the fiscal variables, all significant values at 95%; j Values per capita in Mexican Pesos; k Levels in Thousands of Mexican Pesos; * Hypothesis test of difference of means between values of U&C versus democratic municipalities. Significant difference at 99%.

Source: author’s elaboration with data from the Ministry of Finance of the state of Oaxaca.

Among the hypotheses that we seek to test is whether the municipalities with uses and customs receive higher federal transferences than those municipalities chosen democratically. Although in levels the average amount of transferences received by municipalities chosen by political parties is higher, Table 1 shows that in per capita terms, the municipalities chosen by U&C have received in average higher amounts of transferences than the municipalities chosen by the political party system. In the case of the participations, which are distributed in function of the population component and of municipal income, the difference in favor of municipalities ruled by uses and customs is, in average, almost double.

This average, however, hides the historical trend of transferences to the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca. Figure 1 shows the behavior of the participations and the contributions to the municipalities of Oaxaca, differentiating the political origin. It is clear that in the two types of transferences, the amounts per capita (at 2010 prices) have been historically higher for the U&C municipalities than for the municipalities chosen by the political party system. This observation accumulates evidence in favor of the integration hypothesis, where it is suggested that the transferences are higher for dissident municipalities and have the aim of maintaining cohesion, rather than stimulating their own tax collection (which, as we have seen, is lower in these municipalities).

Source: author’s elaboration with data from the Ministry of Finance of the state of Oaxaca (2011).

Figure 1 Per capita transferences per type of transference, (Pesos MXN, 2010=100).

The last column of Table 1 shows a positive relation between the per capita income of the municipalities and the per capita participations, while they reveal a negative relation with the per capita contributions. Municipalities ruled by uses and customs have a stronger positive correlation with the participations (r=0.5) than the one observed in municipalities chosen democratically (r=0.26); meanwhile, the contributions are related negatively and to a greater degree with municipalities ruled democratically (r=-0.51) than with municipalities ruled by uses and customs (r=-0.40).

The descriptive statistics show interesting features of the federal fiscal system and the political democratic conditions of the municipalities in the state of Oaxaca. In particular, we find in this first approach that the municipalities ruled by uses and customs collect less income of their own and that these in turn have received higher amounts of per capita transferences in average in the study period (2002-2010). The tax collection of their own is related positively with the participations, but negatively with the contributions.

However, up to this point we cannot establish a causal relation between their own tax collection and transferences, and we also do not have an idea about whether the transferences are persistent and for how long. It is necessary to integrate the dynamic interaction of participations, contributions, and municipal income. In the following subsection, we estimate the ARV with the panel data presented in the previous section which allows modelling accurately several characteristics of interest, namely, the causality relationships between variables, the persistence, the strength of relations, etc.

Results

In this study we seek to document evidence about the possibility of a central government looking to maintain the cohesion of municipalities using transferences, which is why the federal transferences can be used a mechanisms for compensation, stability and political integration, rather than as instruments to generate incentives for tax collection by municipalities, as proposed by Inman and Rubinfeld, (1997); Bolton and Roland (1997); Leite-Monteiro and Sato (2003); Sato (2007), privileging the distributive sense and neglecting the compensating sense of the transferences (Peña, J. and L. Wence, 2011).

Evidence in favor of this hypothesis of integration can come from observing, first, a higher amount of federal transferences to municipalities ruled by uses and customs and, second, dissociation between transferences and the capacity to stimulate higher tax collection of their own. The descriptive statistics suggest that the municipalities ruled by uses and customs have received in average higher amounts of transferences per capita. It is also seen that tax collection of their own per capita is related positively with the participations, but negatively with the contributions. However, up to this point we cannot determine the causal direction of their own collection and transferences, so next we determine the dynamic impact of the federal transferences (participations and contributions) on the tax collection by municipalities of Oaxaca.

For municipalities chosen democratically, we expect that a higher amount of participations is related to higher levels of tax collection by the municipalities (income of their own from property and water taxes), as obtained by Cárdenas and Sharma (2011), Benton (1992), Guadarrama (2006), Moreno (2003), and Unda and Moreno (2015). This is the expected relation because the amount that each municipality receives from the Municipal Promotion Fund (Fondo de Fomento Municipal, FFM), a component of federal participations, depends on the local collection of property taxes and from water rights of the two previous years. In addition, the Complementary Fund of the General Participations Fund (Fondo General de Participaciones, FGP) distributes to the municipalities additional participations in proportion to the amount of the property tax collection and the water consumption rights from the previous year. Similarly, because the amount of the contributions received by each municipality in the state of Oaxaca depends on distributive criteria, that is, on the proportion of inhabitants in each one of them, we expect a priori a positive relation between contributions and their own tax collection, as found by Moreno (2003), and Unda and Moreno (2015).

Table 2 shows the parameters estimated of the third-degree ARV with panel data using the Generalized Moments Method8. Two versions of the model (1) were estimated that correspond to the case of the municipalities ruled under the scheme of uses and customs (column a) and the municipalities with the political party regime (column b). Each column is divided into three panels that show the average impact of the lags from each per capita variable on itself and on other variables9.

Table 2 Own tax collection, Participations and Contributions.a

| Usos y Costumbres (a) | Democrático (b) | |||

| □ij | Error Std.b | □ij | Error Std.b | |

| Grupo 1. Recaudación propia de los municipios (predial y agua) | ||||

| Predialt-1 | 0.6026* | 0.1172 | 0.9012* | 0.0913 |

| Predialt-2 | 0.2677* | 0.0677 | 0.0072 | 0.0350 |

| Predialt-3 | -0.0700* | 0.0202 | -0.0271 | 0.0191 |

| Participat-1 | 1.2127* | 0.3250 | 0.4857* | 0.1471 |

| Participat-2 | -0.7797* | 0.1586 | -0.2315** | 0.1058 |

| Participat-3 | -0.3358 | 0.2872 | -0.0722 | 0.1438 |

| Aportat-1 | -1.0261* | 0.2336 | -0.8059 ** | 0.3363 |

| Aportat-2 | 0.4983* | 0.1715 | 0.1559 | 0.0975 |

| Aportat-3 | 0.3756 | 0.4361 | 0.2002 | 0.1462 |

| Grupo 2. Participaciones a los municipios | ||||

| Predialt-1 | -0.0381 | 0.0269 | -0.0069 | 0.0412 |

| Predialt-2 | -0.0068 | 0.0098 | 0.0116 | 0.0137 |

| Predialt-3 | -0.0025 | 0.0041 | 0.0048 | 0.0105 |

| Participat-1 | 0.5595* | 0.0983 | 0.6095* | 0.0577 |

| Participat-2 | 0.3083* | 0.0547 | 0.1570** | 0.0636 |

| Participat-3 | 0.1040 | 0.0870 | 0.1781** | 0.0778 |

| Aportat-1 | -0.2090* | 0.0580 | -0.3566** | 0.1467 |

| Aportat-2 | -0.6015* | 0.0617 | -0.2189 *** | 0.1193 |

| Aportat-3 | 0.0612 | 0.1218 | -0.0831 | 0.0900 |

| Grupo 3. Aportaciones a los municipios | ||||

| Predialt-1 | -0.0410** | 0.0207 | -0.0189 | 0.0296 |

| Predialt-2 | 0.0197** | 0.0080 | 0.0194*** | 0.0104 |

| Predialt-3 | -0.0195* | 0.0037 | -0.0009 | 0.0064 |

| Participat-1 | -0.3825* | 0.0806 | -0.2218* | 0.0534 |

| Participat-2 | 0.3461* | 0.0424 | 0.1351* | 0.0467 |

| Participat-3 | 0.2153* | 0.0707 | 0.2550* | 0.0619 |

| Aportat-1 | 0.6240* | 0.0518 | 0.4793* | 0.1130 |

| Aportat-2 | -0.4132* | 0.0500 | -0.1599*** | 0.0831 |

| Aportat-3 | -0.1580 | 0.1013 | -0.2068* | 0.0709 |

*,**, *** denotes significance at levels of 1%, 5% and 10%. a ARV Panel estimations by the Generalized Moments Method (GMM). Variables transformed through the Helmert de Arellano and Bover method. Models identified precisely according to the Hansen J. b Standard errors adjusted by heteroscedasticity in face of each group.

Source: author’s elaboration with data from the Ministry of Finance of the Government of the state of Oaxaca.

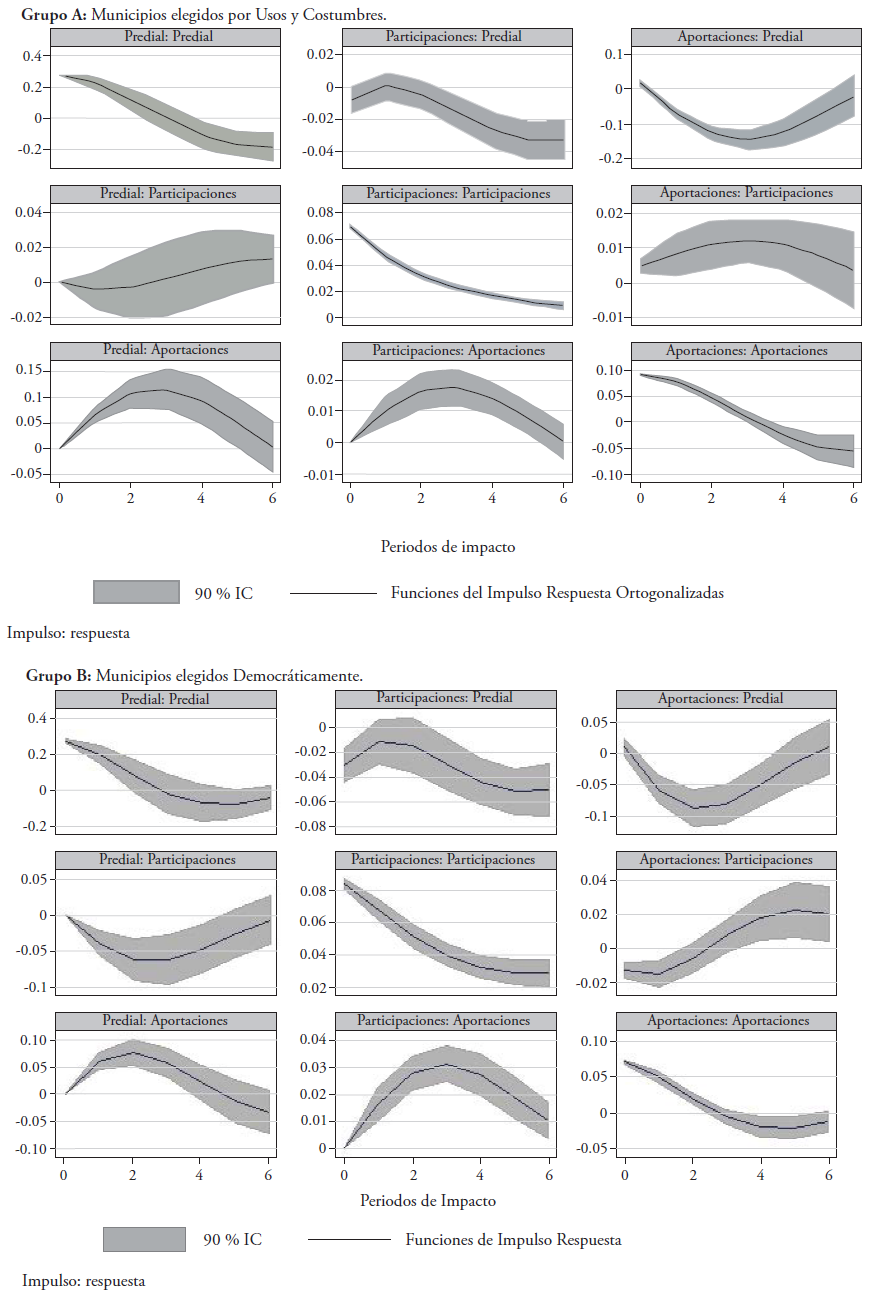

The dynamic relation between the variables can be partially appreciated in Table 2, although in truth the response of fiscal autonomy to shocks from federal transferences is best appreciated with the functions of impulse response shown in Figure 2, divided into two panels that distinguish the cases of political origin listed above: Group A municipalities elected by U&C and Group B municipalities elected by parties. In each case the figures show in the principal diagonal the auto-responses of each variable to shocks from themselves; and in the figures outside the diagonal the responses from each one of them to shocks from other variables.

Source: author’s elaboration based on data from the Ministry of Finance of the state of Oaxaca.

Figure 2: Functions of Impulse Response of the ARV with Panel Data.

Fiscal effort and federal transferences

In the first place, it is generally confirmed that shocks that come from the equation of participations exert a positive and persistent impact on tax collection by municipalities (see central upper figure in Groups A and B). This expected positive response from their own income to shocks from the participations is recorded significantly (at 95 %) for the municipalities ruled by uses and customs (group a). Even when the initial response is null, the tax collection effort increases in the next years. The persistence of the shocks from participations on tax collection by the municipalities ruled by U&C is two years. That is, in addition to the participations being directed to maintaining the political stability of these municipalities, additional positive inertias stimulate the tax collection by these municipalities in the short term10.

In contrast, shocks from the equation of contributions have a negative and significant impact on the municipalities (see upper right figure, groups (A)-(B) of graph 2, respectively). The impact turns out to be of higher magnitude and more persistent (lasting almost four years) for the case of the municipalities ruled by uses and customs. This result suggests that, in contrast to the municipalities chosen democratically, even when the contributions can reinforce the political cohesion and stability of these municipalities, inertias associated with this type of transferences disinhibit the fiscal effort of the municipalities [regularity also reported in other studies such as those by Moreno (2003) and Sour (2004, 2008)]11. The negative association between fiscal effort and contributions can reflect the existence of a hold-up problem, where municipalities decrease the tax collection effort when facing the expectation of lower future transferences-see Zhuravskaya (2000). The latter is consistent with what was established by Hernández and Jarillo (2007), regarding the amount of the Fund for Contributions for Municipal Infrastructure (Fondo de Aportaciones para la Infraestructura Municipal, FISM), which municipalities receive, being influenced by the marginalization index of the municipality.

Substitution of participations and municipal contributions

Now we examine the dynamic relationship between the participations and the municipal contributions. In general, it is observed that the response of the participations to orthogonal shocks from the equation of contributions is negative, significant and highly persistent (see central figure of the last column in each group). The unexpected factors that define the dynamic of the contributions to municipalities of the state of Oaxaca inhibit the response of the participations by prolonged periods of time, in no case under six years. This response seems more pronounced in the municipalities ruled by uses and customs. In sum, the shocks from contributions not only affect negatively the tax collection effort of the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca, but they also disinhibit the dynamic of the participations, more intensely in municipalities ruled by U&C.

In their turn, the response from contributions to shocks from the equation of participations is positive in the short and long term (see lower figure from the second column in each group). In a first moment, right after the shock, the response from the contributions is positive, that is, positive shocks from participations encourage higher amounts of contributions. However, the response turns non-significant for the medium term (between the first and third year) and then they respond positively in the long term (from the third year onward). That is, higher participations encourage higher amounts of contributions with time in the two groups of municipalities.

Auto-responses

Concerning the response of the variables to shocks from themselves, we find that in every case there is a positive, persistent and significant response (see the main diagonal of figures in each group, figure 2). The magnitude of the auto-response of the fiscal effort (upper left figure) is higher than that of the transferences. In particular, regarding the municipalities ruled by uses and customs, we observe that the auto-response of the fiscal effort is initially higher, although it decreases more rapidly and is more unstable than the auto-response of the municipalities chosen democratically. This can indicate that all those shock factors that explain tax collection of their own do not promote a stable behavior of the collection in municipalities ruled by U&C, while in the democratic municipalities, these same shock factors stabilize the behavior of the fiscal effort, and they even make it more persistent.

In its turn, the auto-response of the participations is more persistent than the auto-response of the contributions (approximately six versus two years). While the shock factors that explain the behavior of the participations promote their persistence, in the case of the contributions these factors impact positively, but only in the short term. In turn, neither the level nor the persistence of the participations or contributions are affected by the political origin of the municipalities.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study we research the fiscal relation between the federation and the local political forces from the positive approach of political economy. The hypotheses examined are machine politics, swing vote and political integration. The evidence found does not seem to support for transferences to be directed at groups of political support, and they also do not seek backing from regions with indecisive votes. However, what can be seen is that municipalities with low cohesion to the federalist pact receive a higher amount of transferences and that these are persistent (high transferences tend to manifest for long periods). This observation in particular reinforces the evidence in favor of the hypothesis of integration, which suggests that a central government can use transferences to maintain the stability and political cohesion of the regions, that is, as instruments to ensure political cooperation and integration, in a similar manner than authors such as Inman and Rubinfeld (1997), Sato (2007), and Leite-Monteiro and Sato (2003).

To examine this hypothesis of integration, we took advantage of the political configuration of one of the few regions where the procedure of uses and customs (U&C) is used to elect local governments, an alternative constitutional figure to the traditional partisan struggle. In the first place, we observed that the municipalities ruled by U&C have received in average higher amounts of transferences per capita than the municipalities chosen by political parties. Also, that shocks from contributions impact negatively the tax collection by municipalities, regardless of their political origin. These results have also been found in studies by Bolton and Roland (1997), Alesina and Spolaore (1997), Zhuravskaya (2000), and Unda and Moreno (2015). We interpret a higher tax collection of their own and a negative association with the contributions, as evidence in favor of the hypothesis of integration where transferences can be used as instruments of sociopolitical cohesion, rather than as incentives of municipal autonomy, as in the study by Inman and Rubinfeld (1997). This is in particular the case of municipalities ruled by U&C.

In turn, we find that shocks from the participations impact positively tax collection by municipalities ruled by U&C, the effect however is weak and slightly persistent, while the same impact on the effort of the municipalities ruled by parties is not statistically different from zero12. In net terms in this study we find evidence in favor of the hypothesis of integration; the positive effect of shocks from participations is compensated by the negative impact and higher persistence of shocks from contributions on the tax collection by municipalities13.

Among other results, we also observe that the tax collection per capita by the municipalities elected by political parties is higher than that of municipalities elected by Uses and Customs (U&C). Additionally, we find that the dynamic of the tax collection by municipalities ruled by parties is much more stable and persistent than the municipalities emanated by U&C. The local governments elected by U&C seem to effectively show target fiscal functions different from the municipalities ruled by parties. This result is consistent with what was reported by Wittman (1995), who observes that municipalities with higher political competition should show higher levels of tax collection of their own.

In addition, in this study we find that shocks from the contributions inhibit significantly the dynamics of the participations for prolonged periods of time, of no less than six years, and more intensely in municipalities ruled by U&C. In addition, shocks from the participations increase the tax collection by municipalities in the short term (particularly those ruled by U&C), at the same time they stimulate higher amounts of contributions, in the short and long term, in the two groups of municipalities; these results agree with those found in Cárdenas and Sharma (2011), Benton (1992), Guadarrama (2006), Moreno (2003), and Unda and Moreno (2015).

The hypothesis of political integration by Sato (2006) and Inman and Rubinfeld (1997) suggests that the central government can keep regions in discontentment united by using federal transferences as an adhesion instrument. In this study we find evidence that municipalities with political discontentment have received higher amounts of per capita transferences and that federal transferences inhibit the tax collection effort of the municipalities. As such, the results seem to confirm the notion that transferences are used as mechanisms to ensure stability and cooperation, rather than to stimulate the local fiscal capacity (Inman and Rubinfeld, 1997), or they are used as investment spending to maintain the political unity of the regions (Leite-Monteiro and Sato, 2003), in this case of the municipalities ruled by U&C in the state of Oaxaca.

REFERENCES

Alesina, A., and E. Spolaore. (1997). “On the Number and Size of Nations”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1027-56. [ Links ]

Arellano, M., y O. Bover (1995). “Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error component models”. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 29-51. [ Links ]

Becker, G. S. (1983). A Theory of Competition Among Pressure Groups for Political Influence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics , 371-400. [ Links ]

Bello, R. y J. Espitia (2011). “Distribución regional de las transferencias intergubernamentales en Colombia 1994-2009”, Documentos y Aportes en Administración Pública y Gestión Estatal, vol. 11, núm. 16, pp. 7-50, Argentina. [ Links ]

Benton, J. E. (1992). “The Effect of Changes in Federal Aid on State and Local Government Spending”. Publius, 22:71-82. [ Links ]

Bell, M. E. & Bowman J. H. (1987), «The Effect of Various Intergovernmental Aid Types on Local Own-Source Revenues: The Case of Property Taxes in Minnesota.» Public Finance Quarterly 15: 282-297. [ Links ]

Boadway, R., & Hobson, P. (1993). Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations in Canada (No. 96). Canadian Tax Foundation, Toronto. [ Links ]

Boadway, R. (2002). “The Role of Public Choice Considerations in Normative Public Economics.” In Political Economy and Public Finance: The Role of Political Economy in the Theory and Practice of Public Economics, ed. S. L. Winer and H. Shibata, 47-68. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Bolton, P., & Roland, G. (1997). The Breakup of Nations: a Political Economy Analysis. The Quarterly Journal of Economics , 1057-1090. [ Links ]

Brock, R., & Owings, S. (2003). The Political Economy of Intergovernmental Grants. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 33(2), 139-156. [ Links ]

Cabrera, Fernando y René Lozano (2011). Relaciones Intergubernamentales y el Sistema de Transferencias en México: Una Propuesta de Nivelación Interjurisdiccional, Universidad de Quintana Roo y Miguel Ángel Porrúa, México. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, O. J. y Sharma A. (2011). “Mexican Municipalities and the Flypaper Effect”, Public Budgeting and Finance, 31(3), Wiley-Blackwell, EUA, pp. 73-93. [ Links ]

Díaz Cayeros, Alberto (2004). “El federalismo y los límites políticos de la redistribución”, Gestión y Política Pública, 13(3), segundo semestre, Centro de Investigaciones y Docencia Económicas, México, pp. 663-687. [ Links ]

Dixit, A., Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1997). Common Agency and Coordination: General Theory and Application to Government Policy Making. Journal of political economy, 105(4), 752-769. [ Links ]

Dixit, A. , & Londregan, J. (1996). The Determinants of Success of Special Interests in Redistributive Politics. Journal of politics, 58, 1132-1155. [ Links ]

Dixit, A. , & Londregan, J. (1998). “Fiscal Federalism and Redistributive Politics.” Journal of Public Economics 68 (2): 153-80. [ Links ]

Grossman, P.J. (1994). “A Political Theory of Intergovernmental Grants”, Public Choice, 78:295-304. [ Links ]

Guadarrama, C. V. (2006). Determinantes del gasto estatal en México. Gestión y Política Pública , 15(1), 83-109. [ Links ]

Hernández, Fausto y Jarillo, Brenda (2007). “Transferencias condicionadas federales en países en desarrollo: el caso del FISM en México”, Estudios Económicos, vol. 22, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, pp. 143-184. [ Links ]

Holtz-Eakin, D., Newey, W. y Rosen, H. (1988), “Estimating Vector Autoregression with Panel Data”. Econometrica, 56, 1371-1395. [ Links ]

Ibarra, Jorge, Alfredo Sandoval y Lida Sotres (1999). Participaciones Federales y Dependencia de los gobiernos municipales en México, 1975-1995”, Serie de Documentos de Trabajo del Departamento de Economía, ITESM. [ Links ]

Ibarra, Jorge y Lida Sotres (2009). “Determinantes de la recaudación del impuesto predial en Tamaulipas: Instituciones y zona frontera norte” en Frontera Norte, Vol. 21, Núm. 42, Julio-Diciembre. [ Links ]

Ibarra, Jorge y Héctor González (2009). “Aspectos políticos de la dependencia financiera en los municipios mexicanos”, Serie de Documentos de Trabajo del Departamento de Economía, ITESM. [ Links ]

Ibarra, Jorge (2011). “Entorno político y dependencia financiera de los estados mexicanos”, Gestión y Política Pública , Volumen XXII, Número 1, 1er. semestre de 2013, pp. 3-44. [ Links ]

Inman, R. P., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1996). Designing Tax Policy in Federalist Economies: an Overview. Journal of Public Economics , 60(3), 307-334. [ Links ]

Inman, R. P. , & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1997). “Rethinking Federalism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (4): 43-64. [ Links ]

Isusquiza, E. (2014). “Desigualdad, crecimiento económico y descentralización fiscal: Un análisis empírico para México”, Premio Nacional de Finanzas Públicas, Centro de Estudios de las Finanzas Públicas. http://www.cefp.gob.mx/portal_archivos/convocatoria/pnfp2014/mencionhonorificapnfp2014.pdf [ Links ]

Johansson, E. 2003. “Intergovernmental Grants as a Tactical Instrument: Empirical Evidence from Swedish Municipalities”. Journal of Public Economics 87 (5-6): 883-915. [ Links ]

Labastida, J., N. Gutiérrez y J. Flores (2009), Gobernabilidad en Oaxaca. Municipios de competencia partidaria y de usos y costumbres, México, IIS-UNAM [ Links ]

Leite-Monteiro, M., & Sato, M. (2003). Economic Integration and Fiscal Devolution. Journal of Public Economics , 87(11), 2507-2525. [ Links ]

López, J., & Mayo, B. (2015). Federalismo fiscal. Chiapas y Nuevo León: un análisis comparativo. Economía UNAM, 12(34), 106-123. [ Links ]

Love, I. y Zicchino, L. (2006), “Financial Development and Dynamic Investment behavior: Evidence from panel VAR”. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 46 (2), 190-210. [ Links ]

Mendoza, P. B. (2009). “Participación social armada en Oaxaca. Ejército Popular Revolucionario”, Estudios Políticos, vol. 9, mayo-agosto 2009, pp. 61-83. [ Links ]

Moreno, C. L. (2003). Fiscal Performance of Local Governments in Mexico: The Role of Federal Transfers, México, CIDE-DAP. [ Links ]

Owalabi, Kunle. (2004). “¿La legalización de los usos y costumbres ha contribuido a la permanencia del gobierno priista en Oaxaca? Análisis de las elecciones para diputados y gobernadores, de1992 a 2001,” Foro Internacional, 177, XLIV, 2004 (3), 474-508. [ Links ]

Peña, J. y L. A. Wence (2011). La distribución de transferencias federales para municipios, ¿qué incentivos se desprenden para el fortalecimiento de sus haciendas públicas? INDETEC, revista trimestral No. 115, Oct.-Dic. [ Links ]

Porto, A., & Sanguinetti, P. (2001). Political Determinants of Intergovernmental Grants: Evidence from Argentina. Economics & Politics, 13(3), 237-256. [ Links ]

Ramírez, P. A. (2006). Elecciones por usos y costumbres en México. Revista Letras Jurídicas, 14. [ Links ]

Ruíz-Porras, Antonio y Nancy García-Vázquez, N. (2013), “La reforma hacendaria y las transferencias en los municipios de Jalisco 2005-2011” en Economía Informa, México: UNAM, núm. 381, julio - agosto 2013, publicación bimestral, pp. 29-40. [ Links ]

Ruiz Porras, Antonio y Nancy García-Vázquez (2014), “El Federalismo fiscal y las transferencias planeadas hacia los municipios mexicano: criterios económicos y políticos”, en Espiral, Estudios sobre Estado y Sociedad, Vol. XX, No. 59, Enero/Abril, pp. 69- 86. [ Links ]

Sánchez Almanza, A. (2000). “Marginación e ingreso en los municipios de México, análisis para la asignación de recursos fiscales”, Colección Jesús Silva Herzog, Grupo editorial Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Sato, M. (2007). “The Political Economy of Interregional Grants”, en Public Sector Governance and Accountability Series. Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers: Principles and Practices, Boadway, R. y Shah, A. (Editores), The World Bank, Washington. 173-197. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Finanzas (2011). Datos de la recaudación del impuesto predial de los municipios del Estado de Oaxaca y de las participaciones y aportaciones asignadas a los municipios del Estado de Oaxaca. [ Links ]

Sobel, R. S. & Crowley, G. R. (2014). “Do Intergovernmental Grants Creat Ratches in State and Local Taxes?” Public Choice , 158:167-187. [ Links ]

Sour, Laura (2004). “El sistema de transferencias federales en México: ¿Premio o castigo para el esfuerzo fiscal de los gobiernos locales urbanos?”, Gestión y Política Pública , 13(3), Centro de Investigaciones y Docencia Económicas, México, pp. 733-751. [ Links ]

Sour, Laura (2008). “Un repaso sobre los conceptos de sobre capacidad y esfuerzo fiscal, y su aplicación en los gobiernos locales mexicanos”, Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 23(2), El Colegio de México, México, pp. 271-297. [ Links ]

Stine, W. F. (1994). “Is Local Government Revenue Response to Federal Aid Symmetrical? Evidence From Pennsylvania County Governments in an Era of Retrenchment.” National Tax Journal XLVII: 799-816. [ Links ]

Unda, M. y Moreno, C. (2015). “La recaudación del impuesto predial en México: un análisis de sus determinantes económicos en el período 1969-2010”, Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Nueva Época, Año LX, núm. 225, sept.-dic., pp. 45-78. [ Links ]

Unikel, L. (1976). El desarrollo urbano en México, El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Wittman, D. A. (1995). The Myth of Democratic Failure: Why Political Institutions are Efficient. University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Zhuravskaya, E. V. (2000). Incentives to Provide Local Public Goods: Fiscal Federalism Russian Style. Journal of Public Economics , 76(3), 337-368. [ Links ]

1In this study we consider the fiscal effort as a proxy variable of the autonomy of the municipalities in Mexico.

22For example, if the political affiliation of the municipal president is with PRI, a greater dependency on participations is observed, than that which is seen if the affiliation of the municipal president is with PAN, while the political affiliation to PRD is not statistically significant.

3 This electoral system contains specific voting mechanisms and is based on a series of principles that emanate from the nature of the charges system. The customary law on which this system is based has two characteristics: reiterated practice throughout time and the opinion that it is mandatory. In addition to Oaxaca, this system is recognized constitutionally in the states of Tlaxcala and Chiapas (Ramírez, 2006).

4 Some authors have pointed out, in effect, that the amount of the federal transferences to the municipalities of this region and in particular to Chiapas has increased considerably since then (López and Mayo, 2015).

5 In contrast with the first difference or simple deviation with regards to the mean, the Helmert procedure consists in obtaining the deviations with regards to the mean of the future observations in each variable, which guarantees that the lagged values of the explicative variables continue being valid instruments. This method ensures that the explicative variables during the whole time t are orthogonal with the errors and that the independence of the residues and the square residues (homoscedasticity) is achieved.

6 For more details about the ARV theory with panel data, as well as about problems of identification, estimation, inference and the use of the z i,t lags as instrumental variables, the reader can consult the seminal contributions by Holtz-Eakin et al. (1988).

7ARV estimation with panel data based on the Stata software developed by Love and Ziccino (2006).

9 The stationarity of each variable was ensured using the procedure by Helmert de Arellano and Bolver. The stationarity of the variables was additionally verified with the procedure by Levin-Lin-Chu for unitary roots in panel data.

10 The response from own income to shocks from participations in municipalities chosen by parties is positive and significant only with levels of trust of 90%.

12 The causality only goes from transferences to the tax collection effort of the municipalities. The response from the participations and the contributions to shocks from their own tax collection is not statistically significant.

13 Díaz Cayeros (2004) and Ibarra et al. (1999) have found a positive, significant and persistent impact of the participations on the tax collection by municipalities in Mexico. Consistent with our findings, Sour (2004, 2008) reports that the contributions from Branch 33 discourage municipal tax collection.

Received: June 2016; Accepted: October 2017

![Claudia Rocío Magaña González, Yanga Villagómez Velázquez (Coordinadores). 2018. Hacia una reflexión decolonial de la alimentación en el occidente de México. [Toward a decolonial reflection of the diet in western Mexico] México. Taller Editorial la Casa del Mago, 226 p.](/img/es/next.gif)

texto en

texto en