Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.16 no.2 Texcoco abr./jun. 2019 Epub 25-Feb-2020

https://doi.org/10.22231/asyd.v16i2.1008

Articles

Agrotourism in two municipalities of Sierra Juárez, Oaxaca, Mexico

1MCPA-ITVO. Ex Hacienda de Nazareno, Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca, México. 71230.

2Profesores Investigadores de la DEPI-ITVO. Ex Hacienda de Nazareno, Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca, México. 71230.

3Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Puebla. 3Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca. Ex Hacienda de Nazareno, Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca, México. 71230. (pjuarez@colpos.mx)

Agrotourism is a complementary activity and a strategy in agriculture to strengthen the development of rural communities due to its capacity to generate non-agricultural incomes for peasant families. It integrates economic aspects, of conservation of natural resources, social and cultural aspects, and community participation in a coherent and harmonious way. The objective of the study was to assess the potential for agrotourism, cultural and natural attractions, and infrastructure present in rural spaces of the municipalities of San Miguel Amatlán and Santa Catarina Lachatao in Oaxaca. To assess the viability of agrotourism of the municipalities, a structured interview and the questionnaire was applied to a sample of 81 peasants selected randomly, determining that farmers are adult people (54 years) with low schooling (6.3 years). Inhabitants of the municipality of Lachatao have greater interest in the provision of agrotourism services, highlighting tourism practices in their orchards. The municipalities have sociocultural and natural elements, and a diversity of wild species that belong to their environment which make possible the development of agrotourism activities. It is desirable for the peasant to receive training in agroecological aspects, without losing sight of the fact that coexistence and sharing practices and knowledge will become part of their daily work.

Key words: non-agricultural rural employment; peasant families; rural tourism

El agroturismo es actividad complementaria y una estrategia en la agricultura para fortalecer el desarrollo de comunidades rurales por su capacidad para generar ingresos no agrícolas a las familias campesinas. Integra de manera coherente y armoniosa aspectos económicos, de conservación de recursos naturales, aspectos sociales, culturales y la participación comunitaria. El objetivo de la investigación fue evaluar el potencial agroturísticos, atractivos culturales, naturales e infraestructura que poseen los espacios rurales de los municipios de San Miguel Amatlán y Santa Catarina Lachatao en Oaxaca. Para evaluar la viabilidad agroturística de los municipios se aplicó una entrevista estructurada y el cuestionario a una muestra de 81 campesinos seleccionados aleatoriamente, determinándose que los agricultores son personas adultas (54 años) con baja escolaridad (6.3 años). Los habitantes del municipio de Lachatao tienen mayor interés en la prestación de servicios agroturísticos, destacando las prácticas turísticas en sus huertas. Los municipios cuentan con elementos socio-culturales, naturales y diversidad de especies silvestres propios de su entorno que posibilitan el desarrollo de actividades agroturísticas. Es deseable que el campesino reciba capacitación en aspectos agroecológicos, sin perder de vista que la convivencia y el compartir prácticas y conocimientos se convertirá en parte de su trabajo cotidiano.

Palabras claves: empleo rural no agrícola; familias campesinas; turismo rural

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, tourism at the global scale has acquired greater importance in the economy of some countries; in this sense, Mexico was ninth place receiving international tourists in 2015, with 29.3 million tourists, and it was second place in the American continent, only behind the United States (UNWTO, 2016). In Mexico it is an extremely important economic activity; in 2016, it contributed 7.4 % of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and generated 4 059 500 direct jobs -7.9 % of the total employment- and an increase of 2.6 % was expected in 2017 (World Travel & Tourism Council, 2017). Despite these achievements, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2017) mentions that in Mexico the current tourism model is at a mature stage, that its economic impacts are quite specific, and that its contribution to development is limited. It suggests that a model is implemented which seeks the development of other destinations and the diversification of new touristic products, routes and cluster.

However, this strategy of diversification must be complementary to the existing product of sun and beach and should not be considered a substitute of it. In this context a diversified portfolio must be developed and with a higher value of tourism products, with a market approach that takes advantage to the maximum of different touristic resources, which include gastronomy, ecological products, adventure, gatherings and medical tourism. In addition to tourism diversification and the crisis of the agriculture and livestock sector, rural tourism emerges as a strategy to decrease the problem of low income and precarious employment in rural communities (CONEVAL, 2015; Torres and Padilla, 2015). Presently rural tourism constitutes an alternative form of doing tourism, with its own entity, where the main motivation of the tourist is centered in contact with the rural environment and/or with its resources (Del Barrio et al., 2012). This is why rural tourism becomes a new paradigm to promote development in rural territories.

Regarding the tourism activity that takes place in rural spaces, it is considered to be complex and incipient; in developed countries, like Spain, it contributes nearly 20 000 direct jobs and the services offer grows at an annual rate of 16 % (Instituto de Desarrollo Comunitario, 2015). In Latin America rural tourism has increased from 10 to 15 % between 1996-2006 (Europraxis, T&L Tourism Leisure and Sports, 2012). For the case of Mexico, in 2009 there were a total of 1,239 companies and projects directed at dealing with ecotourism and rural tourism, and the state of Oaxaca occupied the third place with highest offer of rural tourism, only behind Mexico City (Juárez et al., 2009). The state of Oaxaca also stands out for its cultural and natural wealth; it has 16 ethno-linguistic groups, archaeological zones; artistic, gastronomic, musical expressions; geographic, ecosystem and biological diversity (Herrera et al., 2014), placing it as an entity with tourism potential. The objective of the study was to analyze agrotourism, cultural and natural resources, and the infrastructure that people have for the provision of tourism services in the municipalities of San Miguel Amatlán and Santa Catarina Lachatao, in the state of Oaxaca. The hypothesis guiding the study points at the notion that implementation of agrotourism is possible in the municipalities of study because of the existence of a large amount of touristic attractions and, with it, the possibility of generating additional income to agriculture.

Rural tourism and agrotourism as promoters of local development

With the impulse of the Post-Fordism economic model, traditional or mass tourism entered a phase of maturity and a process of change in search for competitiveness to satisfy the new needs and preferences of tourists. The so-called alternative tourism model takes on relevance within this context, seeking to bring personal attention and create custom-made packages for tourists; these factors are more important in the choice of the destination, in addition for the tourist looking for unique life experiences, non-repeatable, personal, in a quality environment (Méndez et al., 2016). In this touristic modality, rural tourism stands out; Zambrano et al. (2017) describes it as a tourism-recreational activity complementary to traditionalist agriculture and livestock activities, where there is the intention to coexist with the inhabitants of communities and rural towns under a perspective of conservation and respect for the environment and natural and sociocultural resources (Varisco, 2016).

The distinctive characteristic of rural tourism services and products, in general, and of agrotourism in particular is the desire to offer visitors the opportunity to enjoy the physical and human environments of rural spaces and, to the extent possible, to participate in activities, traditions and customs of the local population (Szmulewicz et al., 2012). Rural tourism is attributed with positive elements, such as the preservation of habits, values and lifestyles (Baltazar and Zavala, 2015), by influencing the revaluation of native cultures and the recuperation of indigenous products (Díaz-Carrión, 2013; Escobedo, 2014), in addition to driving economic diversification as a strategy to promote local and regional development (Juárez et al., 2009), when allowing the valuation of small-scale farmers’ work, where they are the actors (Garin, 2015; Pariente et al., 2016).

In this sense, local development is defined by Fonseca and González (2015) as a process of economic growth and structural change that leads to an improvement in the standard of living of the local population, where three dimension scan be identified: an economic one, where the local businessmen use their ability to organize the local productive factors with levels of productivity that are sufficient to be competitive in the markets; another one, sociocultural, where the values and the institutions serve as a basis for the development process; finally, a political-administrative dimension where territorial policies allow creating a favorable local economic environment and protecting it from external interferences and driving local development.

With this view of rural tourism, there would be the position that a direct contribution to development and rural welfare would be made with its impulse, through the increase of non-agricultural employment, salaries, poverty reduction and an improvement to health and education (Massam and Espinoza, 2010), that is, a contribution would be made to improving the standard of living of the rural population. This would entail territorial rural development where agriculture ceases to be the main activity of the family economy, to diversify the source of income from non-agricultural rural jobs such as tourism.

Agrotourism is mentioned among the different modalities of rural tourism, which also contributes to the impulse of development in rural zones due to its capacity to favor income generation additional to agriculture (Andrade and Ullauri, 2015; Morales et al., 2015). This is why it is considered to be a strategy to drive development in rural zones (Apodaca-González et al., 2014; Morales et al., 2015), but development in general and specifically recreational activities and tourism do not happen without ups and downs, which include high social costs, and it could be said that it benefits a minority that wields the local or regional power (investors), marginalizing the population that possesses touristic resources. Therefore, rural tourism is taken advantage of by people foreign to the community and farmers are excluded, and are only taken advantage of as employees of low income (Pérez et al., 2010), which is why empowering peasant families is necessary, as well as the active participation of the local population and municipal leadership.

It is considered that agrotourism will be a strategy of local development, if the public policy selects small-scale farmers as the managers and operators of touristic activities, but for this to happen programs must be designed that foster complementary activities, such as touristic territorial planning (tourism infrastructures and superstructures), touristic legislation and regulation, and which strengthen the institutions related to the tourism sector, in addition to performing technical-economic studies of financial and social feasibility, but under a scheme that is not made available to the masses or conventional, to stimulate the preservation of biodiversity and cultural historical heritage (Meave and Lugo-Morín, 2016).

It is important to highlight that the agricultural practices of small-scale producers are identified with the indigenous communities that have demonstrated throughout time that they contribute to the preservation of biodiversity, since there are sociocultural identities where the environment and the biosphere have remained beyond the social system, and the latter beyond the economic scope (Vara and Cuéllar, 2013). An example is the rural landscape, which is considered to be a social construct resulting from a combination of the natural environment and the modes of production, which is visualized through the households and agricultural activities, important resources for agrotourism development. This implies that agrotourism must be framed within the field of sustainability, responsibility that falls on the owner of the place, visitors and tourists (Andrade and Ullauri, 2015), and this is the only way there will be opportunities of income generation for this type of social actors in a sustainable way.

Agrotourism, the same as rural tourism, emerges in some rural spaces because peasant agriculture does not generate enough income to sustain the production unit and its family members. This is explained in part because the primary sector producer of basic grains is excluded from the neoliberal model, since this economic model seeks an evident outsourcing of the economy. Despite this economic tendency of low prices of agriculture and livestock products, agricultural, livestock and forest production continues to be the main economic activity in the rural spaces that produce basic grains; in face of this, it is considered important to diversify their economic activities through the impulse of agro-industrialization of agriculture and livestock products, the production of handcrafts, and the participation of the local population in agrotourism activities that allow promoting employment and non-agricultural rural income (Juárez et al., 2009) based on the multifunctionality of agriculture, as Acevedo-Osorio (2016) mentions.

In this context, De Olivera et al. (2012) consider that rural farmers should be involved in touristic activities in their properties, since tourism is attributed elements that may contribute to increasing income, adding value to products, and diversifying economic activities. Therefore, Juárez and Ramírez (2011) highlight that agrotourism must be stimulated in rural spaces to take advantage of the landscape and cultural resources that producers have. This is where there is a search for the tourist to be part of the social, cultural and productive life of the space that he/she visits, where activities are promoted or offered, such as food preparation (Paül and Araújo, 2012), with rural gastronomy becoming a point of coincidence between agriculture and tourism. Workshops are also promoted of handcrafts, language exchange, knowledge and use of medicinal plants, participation in agricultural activities, as well as in the knowledge and attention of animal species present in the family production units.

METHODOLOGY AND STUDY AREA

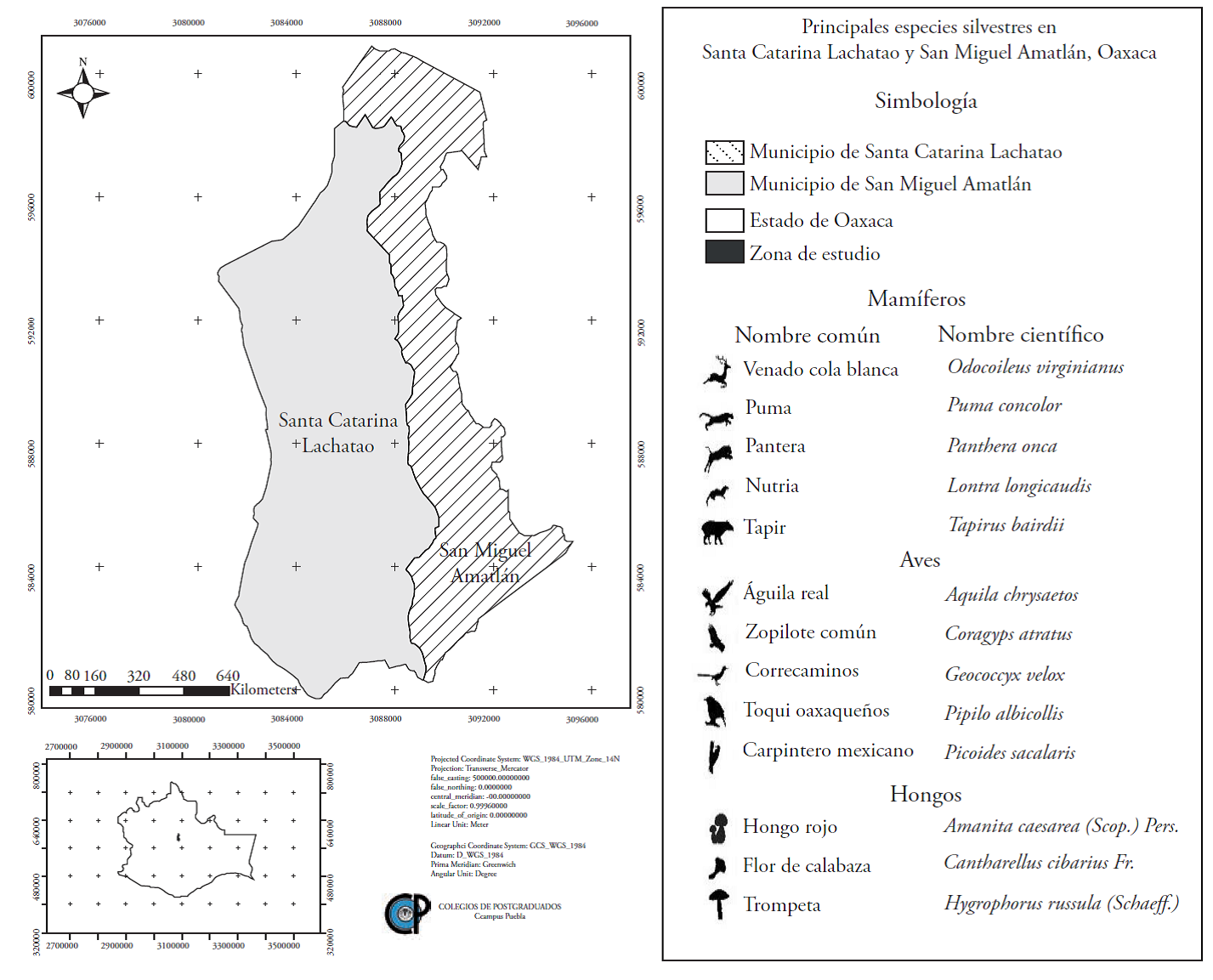

The research was carried out in the municipalities of Santa Catarina Lachatao and San Miguel Amatlán, located northeast of the capital of Oaxaca in Sierra Juárez, District of Ixtlán, between geographic coordinates 17° 06’ 05” and 17° 17’ 32” of latitude north and 96° 20’ 41” and 96° 32’ 24” of longitude west at an altitude between 2000 and 3200 masl (Figure 1), and they are characterized by having small localities, integrated by Zapotec indigenous people. They have basic public services such as electricity, drinking water and health clinics. The municipality of San Miguel Amatlán has 1,043 inhabitants and Santa Catarina Lachatao 1,307 inhabitants. Both municipalities have a high degree of marginalization and are affiliated to the Program for the Development of Priority Zones proposed by the Ministry of Social Development (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, SEDESOL) for 2017.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Figure 1 Spatial location and main species of the municipalities of study.

In the study, a bibliographic review was carried out about the theoretical approaches and concepts of rural tourism and agrotourism. The research was performed with the qualitative and quantitative approaches, which, according to Guerrero-Castañeda et al. (2016), serve to support the explanation of a phenomenon, combining their perspectives in order to provide a broader view of the phenomenon; both do not complement one another as methods, but rather as production of knowledge.

To fulfill the objective proposed in the study, a methodology was designed that was based on obtaining information through field visits, the structured interview, which was done with key informants and people with experience in community charges, and questionnaires with peasants who were selected randomly, with the aim of analyzing and evaluating cultural, environmental and socioeconomic characteristics in the municipalities of study. To calculate the sample size, a randomized stratified sampling technique was used, with a proportional distribution to the size of each municipality (Gómez, 1979):

where N: Size of the population; N

i

: Size of the population of the stratum i;

With:

With an accuracy of 15 % of the mean and a reliability of 95 %, the size of the sample was 81 interview respondents. In the municipality of San Miguel Amatlán, 22 were interviewed and in Santa Catarina Lachatao, 59 peasants devoted to agricultural practices, mainly maize. To analyze the information, parametric and non-parametric statistics were used.

AGROTOURISTIC RESOURCES AS PROMOTERS OF LOCAL DEVELOPMENT

In the study, touristic resources were analyzed that may be offered directly and which the farmer controls, and those that are outside the family production unit. The general characteristics of potential touristic actors (offer) are considered in the design of policies and strategies for the development of products and their diversification, marketing and promotion, investment, development of human capital, and sociocultural and environmental repercussions of tourism. In this sense, it was found that the interview respondents had an average age of 54 years, quite similar (54.6 years) to the one reported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development, Fishing and Diet (Secretaría de Agricultura, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación, SAGARPA) and by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (SAGARPA and FAO, 2014). The families are integrated in average by three people; is it considered that they are small compared to other indigenous spaces, such as the Northeastern Sierra in Puebla, which have in average 4.3 members (Juárez and Ramírez, 2014). They have low schooling (6.3 years) compared to the national average (8.9 years) for the population of 15 years or more in 2012 (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, 2015). Age was associated negatively to the level of study, which is why older farmers have a lower level of schooling (r=-0.60; p<0.01). This shows that there is ageing in the population, which has low levels of schooling that can influence negatively the operation and management of touristic projects.

Regarding the touristic resources that interview respondents have, sociocultural and productive resources can be mentioned. Their language stands out among the first kind, and in Amatlán (50 %) and Lachatao (85 %) interview respondents -older adults- speak Zapotec and Spanish; these results are similar to those reported by the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas, INALI, 2012), which points out that speakers of an indigenous language are generally older people, indicating that the younger that farmers are the lower probabilities that they will speak Zapotec. Despite this, they have an important resource to make an incursion into idiomatic tourism, where culture is the most important aspect to develop, but it also induces to purchasing services that belong in tourism, such as transport, housing, restoration, excursions, etc., elements that provide added value to teaching a language.

Another important resource in the tourism activity is cultural heritage, since it is considered currently as a tourism resource of great potential, and the patrimonialization of the “dietary culture” takes place now within the tourism market and its benefits for local development, which is why rural gastronomy is an important part of the culture and is considered a legacy of the civilizations that is part of their identity and reflects the life of people (Xavier, 2017). Gastronomy in the municipalities of study is not the exception, which is rich and diverse, and represents an opportunity to be offered as gastronomy-touristic product; among the typical dishes of Amatlán, amarillo and mole de guajolote stand out, while in Lachatao, chichilo de pollo and atole colorado (chili and annatto). These are touristic resources that must be promoted; Xavier (2017) states that the valuation of local dietary patrimony has an economic role and is a motor for the territories of agricultural production, proposing new development paths and building new forms of territorial attraction. On their part, Santana et al. (2012) found that the most sought after activity by tourists is gastronomy, since they see it as a possibility to understand the culture of a place, and some are interested in knowing and preparing the dishes, as well as the rituals and habits associated to their preparation.

Another touristic resource is traditional medicine, which is focused primarily on spiritual cleanses, post-partum care, and cures for the soul (frights, anxiety, fears), as well as stomach and respiratory diseases; they also provide temascal baths and sobas (body massages). To prepare or perform them they use a diversity of plants; 45 were recognized, among which the ones most frequently used to treat stomach pains are pennyrile (Mentha pulegium), rue (Ruta graveolens) and spearmint (Mentha spicata). Cruz-Casallas et al. (2017) mention that ancestral knowledge has been historically used by indigenous communities in the solutions to their health problems; therefore, the preservation of traditional medicine is subject to the capacities of transcending their uses and practices from generation to generation, and in the ability to effectively incorporate this knowledge in the life plans of the different communities. In this sense, traditional medicine can be offered as an agrotourism product, taking advantage of the wisdom of traditional medicine.

Another touristic attraction can be built with agriculture and livestock practices; Mas (2013) mentions that these are activities that attract tourists. Therefore, it is fundamental to understand the characteristics of the production unit of inhabitants in Amatlán, which cultivate in average 1.8 ha, and in Lachatao, 2.08 ha, in a regime of communal property. This type of farms are characterized for sowing “milpa”, a production system based on the cultivation of small extensions where fundamentally maize is cultivated (Nava et al., 2013). The production unit is a family good that can be considered a touristic resource because of interspersed sowing of crops, among them different types of maize races, beans, squash and other species, and as non-interspersed crops the ones that stand out are broad bean (Faba vulgaris), pea (Pisum sativum) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), which means that there is landscape wealth in the local agroecosystems, but also due to traditional management practices, since they use wooden ploughs pulled by animals in land farming. This type of agricultural practices can represent an attraction for tourists when evoking the past or history, and respect for nature in food production.

Another touristic attraction is represented by fruit orchards, of variable size and structure, such as agroforestry systems, where apple (Pyrus malus) and peach (Prunus pérsica) trees predominate, but there are also plum (Prunus domestica) and pear (Pyrus spp.) trees. Of the inhabitants in Amatlán, 88.9 % use the harvest obtained for auto-consumption. In Lachatao, only 3.6 % devote it to preparation of jams, jellies and other derivatives; the rest is sold in the locality.

There are also bulls that are used as animal traction force in the cultivation tasks and donkeys for the load. At the level of backyard they raise fowl, where hens and turkeys predominate, used primarily for auto-consumption. These are touristic resources which, according to Morales et al. (2015), can be promoted as agrotourism products through the promotion of practices such as feeding backyard animals, after rearranging the space.

The touristic resources present outside the family production unit and which may be complement or principal attraction for tourists are diverse and very rich. Those of greatest importance are the species of wild animals. Lavariega et al. (2012) report the existence of 139 of them for Sierra Juárez, which houses 10 % of the natural wealth of the planet (Palomino et al., 2016). The interview respondents mentioned that there are 22 mammal species in their municipalities, with ocelot, deer, puma, panther, wildcat and spider monkey standing out (Table 1). The diversity of species identified by the interview respondents has a high value for tourists, but there should also be care that this type of tourism be highly respectful to animal species.

Table 1 Mammal species identified.

| Nombre común | Nombre científico | Nombre común | Nombre científico |

| Tlacuache | Didelphis sp. | Comadreja | Mustela frenata |

| Coyote | Canis latrans | Tejón | Nasua narica |

| Armadillo | Dasypus novemcinctus | Zorrillo | Conepatus mesoleucus |

| Tigrillo | Leopardus wiedii | Pecarí de collar | Pecari tajacu |

| Ardilla gris | Sciurus aureogaster | Gato montés | Lynx rufus |

| Venado cola blanca | Odocoileus virginianus | Nutria | Lontra longicaudis |

| Tepezcuintle | Cuniculus paca | Tapir | Tapirus bairdii |

| Puma | Puma concolor | Conejo | Sylvilagus spp. |

| Pantera | Panthera onca | Tlacomixtle | Bassariscus sumichrasti |

| Zorro gris | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | Mapache | Procyon lotor |

| Tuza | Thomomys umbrinus | Mono araña | Ateles geoffroyi |

Source: authors’ elaboration.

The municipalities of study were located in one of the so-called Areas of Importance for Bird Conservation (Áreas de Importancia para la Conservación de las Aves, AICA-220) (Avesmx/Conabio, 2015), because of the high number of species they house (483), representing 44 % of the national total and at least 66 endemic and quasi-endemic species (Santos et al., 2013; Rosas and Correa, 2016). In the study area peasants identified 24 species; for their touristic importance, the ones that stand out are different types of eagles, roadrunners, owl, barn owl, and Mexican woodpecker (Table 2).

Table 2 Species of birds identified

| Nombre común | Nombre científico | Nombre común | Nombre científico |

| Águila real | Aquila chrysaetos | Correcaminos | Geococcyx velox |

| Aguililla cola-roja | Buteo jamaicensis | Toquí de collar | Pipilo ocai |

| Chotacabras menor | Chordeiles acutipennis | Atlapetes gorra rufa | Atlapetes pileatus |

| Zopilote común | Coragyps atratus | Toquí oriental | Pipilo erythrophthalmus |

| Zopilote aura | Cathartes aura | Toquí oaxaqueño | Pipilo albicollis |

| Paloma de collar | Columba fasciata | Junco ojo de lumbre | Junco phaeonotus chipeala blanca |

| Tórtola cola larga | Columbina inca | Golondrina aliaserrada | Stelgidopteryx serripennis |

| Cuervo común | Corvus corax | Chipeala blanca | Myioborus pictus |

| Chara crestada | Cyanocitta stelleri | Chipe rojo | Ergaticus ruber |

| Picaflor canelo | Diglossa baritula | Carpintero mexicano | Picoides scalaris |

| Chipe de montaña | Myioborus miniatus | Búho cornudo | Bubo virginianus |

| Gallina de monte | Dendrortyx macroura | Tecolote serrano | Glaucidium gnoma |

Source: authors’ elaboration.

In addition to the animal and bird species, and in the municipalities of study, the farmers interviewed identified six species of fungi that they use in their gastronomy. Given their importance in the municipality of San Miguel Amatlán, the “Fungi Fair” is held annually, activity that is an attraction for tourists.

According to Jiménez et al. (2016), this type of species should be considered within the recreational activities centered in the knowledge, collection and consumption of wild edible fungi and, therefore, represent a product within mycological tourism (Table 3). These events are considered by inhabitants as attractive and of interest for tourists.

Table 3 Species of fungi identified.

| Nombre común | Nombre científico |

| Hongo rojo | Amanita caesarea (Scop.) Pers. |

| Flor de calabaza | Cantharellus cibarius Fr. |

| Chimequito | Cantharellus tubaeformis Fr. |

| Espinitas | Hydnum repandum L. |

| Trompeta | Hygrophorus russula (Schaeff.) Kauffman. |

| Cresta de gallina | Hypomyces lactifluorum (Schwein.) Tul. & C. Tul |

Source: authors’ elaboration.

In terms of the type of vegetation, farmers manifested that there are six types of vegetation: deciduous forest, pine forest, oak forest, pine-oak forests, sacred fir forest, and relicts of mountainous cloud forest. There are also beautiful landscapes, such as mountains, waterfalls, caves, rivers and streams that are favorable for ecotourism. The peasants interviewed mentioned that their state of conservation is good; this explains that indigenous peoples consider them essential because they are part of their material patrimony or natural capital and social reproduction (Flora et al., 2004); their conservation is also attributed to the forms of Communal Government, since they are the basis for optimizing local practices and procedures in the management of natural resources (Gasca, 2014).

It is considered that the municipalities of study have important touristic resources, although to convert them into products it is necessary to see if there are appropriate conditions to provide touristic services or make incursions in them. In this regard the characteristics of the households are analyzed; in average they have three rooms, two are for sleeping and one to prepare their foods, and they have drinking water, electricity and rest rooms. Their construction is considered attractive and in accordance to the landscape, since it has the characteristics of vernacular housing; their walls are adobe, with sheet roofs and cement floor. In a study performed in an indigenous zone of the state of Puebla by Juárez and Ramírez (2011), they mention that the houses are inhabited in average by 4.6 members and have a room for resting and another for cooking, and they do not have the services of drinking water and drainage. These results show that households in the municipalities of study present better conditions to offer the service of lodging.

With regards to the participation of interview respondents in the provision of touristic services, it was found that they think that rural tourism is related mostly to spending time with people and with lodging, as well as communicating the uses and customs of inhabitants in their communities and daily tasks. Those who are between 30-50 years old are willing, to a greater extent, to offer rural tourism activities. It was also found that the interview respondents from Lachatao showed greater interest in the provision of these services, with touristic practices in their orchards standing out (Table 4).

Table 4 Products or services that inhabitants from Amatlán and Lachatao would offer.

| Tipo de servicio | Municipio | ||

| Santa Catarina Lachatao (%) | San Miguel Amatlán (%) | ||

| Actividades agrícolas y ganaderas | 73 | 27 | |

| Talleres gastronómicos | 75 | 25 | |

| Prácticas en huertas | 100 | 0 | |

| Hospedaje rural | 60 | 40 | |

| Todos los servicios | 80 | 20 | |

| Total | 75 | 25 | |

Source: authors’ elaboration.

Also, and in important percentages, they are willing to offer services as hotel and lodging, which means that they are considering rural tourism as an activity which may contribute to improving their economic conditions. Public administration plays an important role here in tourism promotion and this should be expressed through investment in programs directed at this type of projects to influence directly the planning, development and execution of touristic activities (Pérez-Ramírez and Zizumbo-Villarreal, 2014).

In this sense it should be taken into account that the municipalities of study are ruled by uses and customs. It is a traditional form of sociopolitical organization that allows the election of public charges to be made through internal and autonomous normative systems (Canedo, 2008); this scheme of governance refers to a series of formal and informal arrangements that define the way in which decisions are made to be implemented (Gasca, 2014). This has allowed the collective participation in decision making of the municipalities where the importance of the civic and religious structure stands out, whose strength and integrity allow cementing the social cohesion and self-management among the population, given that the participation of social actors is an essential element for the development of tourism projects (Méndez et al., 2016). According to the perception of interview respondents, this sociopolitical scheme has had an impact on the municipalities in study to develop ecotourism activities in an adequate and successful way.

The results bring to light that there is the possibility of success in the promotion of agrotourism projects, since these municipalities have the potential of offering the service and they have the market. In this regard, Juárez and Ramírez (2007) consider that if tourism projects are promoted, these will contribute to the conservation of natural resources; however, it should be planned, since it is possible that low-intensity tourism becomes mass tourism. This would present a risk for rural communities, exerting greater pressure on the natural resources available, situation that suggests defining the load capacity of agrotourism services that may be present in the municipalities under study. It is possible to conclude that the practice of agrotourism in the family production units can be viable, since it has a range of touristic resources that can be widely valued by tourists.

CONCLUSIONS

From the study it is derived that San Miguel Amatlán and Santa Catarina Lachatao have the characteristics favorable for the development of agrotourism activity, considering their social capital, interesting cultural resources such as agrarian techniques, lifestyles, gastronomy, festivities, scheme of organization and language, as well as their natural resources, with the beautiful landscapes, climate, vegetation and biodiversity standing out.

The farmers who are willing to make incursions into agrotourism activities are mature people with basic education and characterized for being small-scale farmers who own smallholdings and practice rainfed agriculture in small plots, sowing fundamentally basic crops with traditional productive techniques. Performing agricultural practices in their fruit orchards also stands out, which have a high touristic potential, representing an opportunity for development for local inhabitants. In this sense, the results show that inhabitants in the municipality of Lachatao have greater interest in the provision of these services, highlighting touristic practices in their orchards.

In their backyard they can offer activities of diet and animal care, activity directed at young people and children with educational purposes, and of discovery of the rural environment. Here, agrotourism may be constituted for the farmer into an activity that can be remunerated and contribute to the investments carried out in agricultural practices. In this sense, it is considered that it is favorable to offer land farming activities in a traditional way in the farmers’ plots.

In addition, gastronomic workshops can be offered in their households to make incursions into gastronomic tourism that seeks to fit in the local productive structure, which is why local gastronomy is a touristic attraction that may help to revalue the peasant production model when supplying raw materials for the elaboration of foods, since most of the gastronomic tourists demand natural agrarian products or elaborated traditionally, and typical of the region. The interview respondents are willing to offer this type of activities as a touristic product where women homemakers would be the main actors.

The patron saint festivities, fairs and mystical experiences, the Zapotec language, culinary knowledge, and alternative or traditional medicine represent big opportunities to offer a tourism product.

It is also important to point out that the municipalities of study have a singular wealth in wild species, which are appreciated by tourists, and from this type they can diversify into a series of touristic activities in the study zone. In general terms, agrotourism would be a source of social welfare and would generate diverse employment and complementary income for the families, in addition to supporting to a great extent the economy of future generations, without neglecting the environmental and cultural axis, established by the principle of sustainability.

This type of activities should also be planned so that they do not become massive and constitute a risk of environmental degradation. It should be planned considering the productive axis of the farmland as fundamental generator of products and services for “agrotourism”, which is why it is desirable for the peasant to receive training in agroecological aspects and in the provision of tourism services, without losing sight of the fact that coexistence and sharing practices and knowledge will become part of their daily work. Finally, it can be said that the municipalities of study have the natural and cultural resources, and a diversity of wild species that allow having a diversity of agrotourism resources, in addition to presenting a sociopolitical scheme known as “uses and customs” that allows the inhabitants to participate and become involved in the processes of development of agrotourism.

LITERATURA CITADA

Acevedo-Osorio, Álvaro. 2016. Monofuncionalidad, multifuncionalidad e hibridación de funciones de las agriculturas en la Cuenca del Río Guaguarco, Sur del Tolima. Luna Azul. Núm. 43, julio-diciembre 2016. DOI: 10.17151/luaz. 43.12. [ Links ]

Andrade, María, y Narcisa Ullauri. 2015. Historia del agroturismo en El Cantón Cuenca Ecuador. PASOS. Vol. 13, Núm. 5, febrero 2015. [ Links ]

Apodaca-González, Claudia, José Pedro Juárez-Sánchez, Benito Ramírez-Valverde, y Rodrigo Figueroa. 2014. Revitalización de fincas cafetaleras por medio del turismo rural: caso del municipio Coatepec, Veracruz. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. Núm. 9, noviembre. [ Links ]

Baltazar, Obdulia, y Jesús Zavala. 2015. El turismo rural como experiencia significativa y su estudio desde la fenomenología existencial. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas . Vol. 6, Núm. 6, agosto-septiembre. [ Links ]

Canedo, Gabriela. 2008. Una conquista indígena. Reconocimiento de municipios por usos y costumbres en Oaxaca (México). La economía política de la pobreza/Alberto Cimadamore (comp.) Buenos Aires: CLACSO. Marzo. [ Links ]

Cruz-Casallas, Nubia, Euciris Guantiva, y Agustín Martínez. 2017. Apropiación de la medicina tradicional por las nuevas generaciones de las comunidades indígenas del Departamento de Vaupés, Colombia. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. Vol. 16, Núm. 3, mayo. [ Links ]

Avesmx/Conabio. Portal aves de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Gobierno de México. 2015. In:http://avesmx.conabio.gob.mx/Es-peciesRegion.html#AICA_220. [ Links ]

CONEVAL (Consejo Nacional para la Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social). 2015. Resultados de la medición de pobreza 2014. México, D.F. 30 p. [ Links ]

De Olivera, Eurico, Silvio Gonçalves, y María Rosa. 2012. Evolución de la renta, empleo y sueldos en propiedades rurales que ofrecen agroturismo y turismo rural en la Mitad Sur de Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil (1997-2011). El Periplo Sustentable. Núm. 23, Julio-Diciembre. [ Links ]

Del Barrio, Salvador, Lorenza López, y Dolores Frías. 2012. El tipo de incentivo como determinante en el atractivo de la promoción de venta en turismo rural. Efecto moderador del sexo, la edad y la experiencia. Revista Española de Investigación de Marketing ESIC. Vol. 16, Septiembre. [ Links ]

Díaz-Carrión, Isis. 2013. Mujeres y mercado de trabajo del turismo alternativo en Veracruz. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio. Vol.13, Núm. 42, septiembre. [ Links ]

Escobedo, José Sergio. 2014. El turismo rural, un desafío para pequeños agricultores. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas . Núm. 9, noviembre. [ Links ]

Europraxis, T&L Tourism Leisure and Sports. 2012. Diagnostico Turismo de Naturaleza en el Mundo: Plan de Negocio de Turismo de Naturaleza en Colombia. Documento electrónico. Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo, República de Colombia. In: http://file:///C:/Users/DEPI%2011/Downloads/2012%20diagnos-tico-turismo-de-naturaleza-entregable-i%20(1).pdf [ Links ]

Flora, Cornelia, Jan Flora, and Susan Fey, S. 2004. Rural Communities Legacy + Change. Second edition Westview Press, Colorado U.S.A. 372 p. [ Links ]

Fonseca, María, y David González. 2015. Turismo rural y desarrollo local, en El Colomo, municipio Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit. In: Stella Arnaiz y Judith Juárez (coord). Desarrollo, Crisis y Turismo. México. Universidad de Guadalajara. pp: 632- 375. [ Links ]

Garin, Alan. 2015. Turismo rural en el acomuna de Villarica, Chile: Institucionalidad y emprendedores rurales. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo. Vol. 24, Núm.1, enero. [ Links ]

Gasca, José. 2014. Gobernanza y gestión comunitaria de recursos naturales en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca. Región y Sociedad. Vol. 26, Núm. 60, mayo-agosto [ Links ]

Gómez, Roberto. 1979. Introducción al muestreo. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias en Estadística. Centro Estadística y Cálculo. Colegio de Postgraduados. Chapingo México. [ Links ]

Guerrero-Castañeda, R.F., Lenise do Prado, M., y Ojeda-Vargas, M.G. 2016. Reflexión crítica epistemológica sobre métodos mixtos en investigación de enfermería, In Enfermería Universitaria. Vol. 13. [ Links ]

Herrera, Alfonso, Jorge Martínez, María Moreno, Jonatan González, Miguel Backhoff, y Emmanuel García. 2014. Diagnóstico del transporte Aéreo comercial en el Estado de Oaxaca. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes e Instituto Mexicano del Transporte. Publicación Técnica No. 421. pp: 3-15. [ Links ]

IDC (Instituto de Desarrollo Comunitario). 2015. Tendencias del turismo rural en España. In: http://www.idcnacional.org/?option=com_content&id=162:tñendencias-turismo-rural-espana &Itemid=122. [ Links ]

INALI (Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas). 2012. Lenguas indígenas nacionales en riesgo de desaparición: Variantes lingüísticas por grado de riesgo. 2000 / INALI; coordinadores: Embriz, Arnulfo y Óscar Zamora. México. [ Links ]

INEE (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación). 2015. Panorama educativo de México 2014. Indicadores del sistema educativo nacional, educación básica y media superior; coordinadores: Robles, Héctor y Mónica Pérez. Editorial Indicadores Educativos. 132 p. [ Links ]

Jiménez, Edurne, Humberto Thomé, y Cristina Burrola. 2016. Patrimonio biocultural, turismo micológico y etnoconocimiento. El Periplo Sustentable . Núm. 30, enero-junio. [ Links ]

Juárez, José Pedro, y Benito Ramírez-Valverde . 2007. El turismo rural como complemento al desarrollo territorial rural en zonas indígenas de México. Scripta Nova. Vol. 11, Núm. 236, abril. [ Links ]

Juárez, José Pedro , Benito Ramírez-Valverde , y María Guadalupe Galindo. 2009. Turismo rural y desarrollo territorial en espacios indígenas de México. Investigaciones geográficas (Esp). Núm. 48. [ Links ]

Juárez, José Pedro , y Benito Ramírez-Valverde . 2011. Casas rurales y agroturismo en la Sierra Nororiente del estado de Puebla, México. In: Juárez, S. J. y. Ramírez-Valverde, B. Turismo rural experiencias y desafíos en Iberoamérica. Texcoco, Estado de México. pp. 87-116. [ Links ]

Juárez, José Pedro , y Benito Ramírez-Valverde . 2014. Posibilidades de turismo social en espacios rurales: estudio en la Sierra Nororiente de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias. Pub. Esp. Núm. 9, septiembre-noviembre. [ Links ]

Lavariega, Mario, Miguel Briones, y Rosa Gómez. 2012. Mamíferos medianos y grandes de la Sierra de Villa Alta, Oaxaca, México. Mastozoología Neotropical. Vol. 19, Núm. 2, julio-diciembre. [ Links ]

Mas, Lorena. 2013. Diseño de un proyecto de agroturismo para La Solana en Bélgida (Valencia, España). Tesis de grado en Gestión Turística. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. 52 p. [ Links ]

Massam, Bryan H., y Rodrigo Espinoza. 2010. Turismo, ¿a quién beneficia? In: Turismo comunitario en México. Distintas visiones ante problemas comunes. Chávez Dagostino, Rosa María, Edmundo Andrade Romo, Rodrigo Espinoza Sánchez Miguel Navarro Gamboa (coord), Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de la Costa. pp: 25-31. [ Links ]

Meave, Mariana, y Diosey Lugo-Morín. 2016. Capacidad de carga asignable al agroecoturismo en áreas protegidas de Bolivia. Luna Azul . Núm. 42, enero-junio. [ Links ]

Méndez, Alberto, Arturo García, Manuel Santos-Olmo y Verónica Ibarra. 2016. Determinantes sociales de la viabilidad del turismo alternativo en Atlautla, una comunidad rural del Centro de México. In: Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, Vol. 2016, agosto. [ Links ]

Morales, Luis, Agustín Cabral, Alfredo Aguilar, Lizzette Velzasco y Ortensia Holguín. 2015. Agroturismo y competitividad, como oferta diferenciadora: el caso de la ruta agrícola de San Quintín, Baja California. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios. Núm. 37, julio-diciembre. [ Links ]

Nava, Fidel, Miguel Herrera, Armando García, y Jaime Ruiz. 2013. Situación actual del empleo de la tracción animal en los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca, México: Análisis crítico. Ciencias Técnicas Agropecuarias. Vol. 22, No. 1, enero-marzo. [ Links ]

OECD (Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos). 2017. Estudio de la Política Turística de México. Resumen Ejecutivo, Evaluación y Recomendaciones. Secretario General de la OCDE. 38p. [ Links ]

Palomino, Bertha, José Gasca, y Gustavo López. 2016. El turismo comunitario en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca: perspectiva desde las instituciones y la gobernanza en territorios indígenas. El Periplo Sustentable . Núm. 30, enero-junio. [ Links ]

Pariente, Elí, Jorge Chávez, y Carlos Reynel. 2016. Evaluación del potencial turístico del distrito de Huarango San Ignacio, Cajamarca, Perú. Ecología Aplicada Vol. 15, Núm. 1, junio . [ Links ]

Paül, Valerià y Noelia Araújo. 2012. Agroturismo en entornos periurbanos: enseñanzas de la iniciativa holeriturismo en el parc agrari del Baixl lobregat (Cataluña). Cuadernos de Turismo. Núm. 29, [ Links ]

Pérez, Adriana, José Pedro Juárez, Benito Ramírez-Valverde , y Fernanda Cesar. 2010. Turismo rural y empleo rural no agrícola en la Sierra Nororiente del estado de Puebla: caso red de Turismo Alternativo Totaltikpak, A. C. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía , UNAM. Núm. 71. [ Links ]

Pérez-Ramírez, Carlos, y Lilia Zizumbo-Villarreal. 2014. Turismo rural y comunalidad: impactos socioterritoriales en San Juan Atzingo, México. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural. Vol. 11, Núm. 73, mayo. [ Links ]

Rosas, Mara, y David Correa. 2016. El ecoturismo de Sierra Norte, Oaxaca desde la comunalidad y la economía solidaria. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo. Vol. 13, Núm. 4, octubre-diciembre. [ Links ]

Santana Agustín, Alberto Rodríguez, y Pablo Díaz. 2012. Turismo, turistas y tipologías en la Reserva de la Biosfera de Fuerteventura. In: Agustín Santana, Alberto Rodríguez y Pablo Díaz . (coords) Responsabilidad y Turismo. Revista de turismo y patrimonio cultural PASOS . Cap. X Colección PASOS Edita nº 10. Tenerife (España). pp: 187-202. [ Links ]

Santos, Andrea Rosario, Ana Hernández, Mario Lavariega, y Rosa Gómez e. 2013. Diversidad de aves en cultivares de Santa María Yahuiche, Sierra Madre de Oaxaca, México. Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas, Vol. 4, Núm.6, septiembre. [ Links ]

SAGARPA y FAO. 2014. Estudio sobre el envejecimiento de la población rural en México. Secretaría de Agricultura, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación México y la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. 43 p. [ Links ]

SEDESOL (Secretaria de Desarrollo Social). Catálogo de Localidades. Sistema de Apoyo para la Planeación del PDZP. Unidad de microrregiones dirección general adjunta de planeación microrregional 2017. In: http://www.microrregiones.gob.mx/catloc/LocdeMun.aspx?tipo=clave&campo=loc&ent=20&mun=262 . (Febrero 2017). [ Links ]

Szmulewicz, Pablo, Gutiérrez Cecilia, y Winkler Karen. 2012. Asociatividad y agroturismo: evaluación de las habilidades asociativas en redes de Agroturismo del sur de Chile. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo . Vol. 21, núm. 4, julio-agosto. [ Links ]

Torres, Mireya, y Juan Padilla. 2015. Pobreza rural multidimensional en Zacatecas. Migración y Desarrollo. Vol. 13, núm. 24, enero-junio. [ Links ]

Vara, Isabel, y Mamen Cuéllar. 2013. Biodiversidad cultivada: una cuestión de coevolución y transdisciplinariedad. Ecosistemas. Vol. 22, núm. 1, [ Links ]

Varisco, Alejandra. 2016. Turismo Rural: Propuesta metodológica para un enfoque sistémico. PASOS . Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural. Vol. 14, Núm. 1, enero. [ Links ]

UNWTO (World Tourism Barometer). 2016. International Tourist Arrivals by Country of Destination. Statistical Annex. Vol. 14. 6 p. [ Links ]

World Travel, and Tourism Council. 2017. Travel & Tourism; economic Impact 2017: México. WTTC, Londres, 24 p. [ Links ]

Xavier, F. 2017. Reflexiones sobre el patrimonio y la alimentación desde las perspectivas cultural y turística, In Anales de Antropología, Vol. 51, julio-diciembre. [ Links ]

Zambrano, Fernando, Delymar González, y Rossy Peñaloza. 2017. El turismo rural una visión desde el ámbito internacional, nacional y del estado Táchira-Venezuela. Revista de investigación en administración e ingeniería. Vol.5, núm. 1, febrero. [ Links ]

Received: June 2017; Accepted: September 2017

texto en

texto en