Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.16 no.1 Texcoco ene./mar. 2019

Articles

The work of government institutions in Guanajuato, around gender violence against rural women: analysis through a case study

1 Departamento de Estudios Sociales, Universidad de Guanajuato.

This study has the objective of analyzing, through a case of gender violence against a rural woman, how the institutions that should support women do not, and how they have gender prejudices and minimize these situations. This study is part of a research project about gender violence and femicide violence in the south of the state of Guanajuato that takes place in rural communities of the southern region of the state. We begin from the assumption that women who are immersed in situations of violence can be pressured by their direct family members, by their spouses or by government institutions to not denounce events of gender violence and, when they do denounce, to cease the claims and continue with this situation that can lead to their deaths.

Key words: rural women; gender violence; institutional violence

El presente trabajo tiene como objetivo analizar, a través de un caso de violencia de género hacia una mujer rural, cómo las instituciones que deberían apoyar a las mujeres no atienden, tienen prejuicios de género y minimizan estas situaciones. Este trabajo forma parte de un proyecto de investigación sobre violencia de género y violencia feminicida en el sur del estado de Guanajuato que se lleva a cabo en comunidades rurales del sur del estado de Guanajuato. Partimos del supuesto de que las mujeres que se encuentran en situaciones de violencia pueden ser presionadas tanto por sus familiares directos, por sus parejas y por instituciones gubernamentales para que no denuncien hechos de violencia de género y, en caso de hacerlo, levantar las demandas y continuar con esa situación que puede llevarlas a la muerte.

Palabras clave: mujeres rurales; violencia de género; violencia institucional

Introduction

According to recent data from the Endireh (National Survey on the Dynamics of Relationships in Households, 2016), the prevalence of violence in Mexico among women of 15 years and older throughout their life was 66.1 % in 2016, 62.8 % in 2011 and 67 % in 2006. From 2006 to 2011 the prevalence of violence decreased from 67 to 62.8 %, but in the most recent survey this index has increased to 66.1 %. All the data are very high because they indicate that six out of ten women have experienced some type of violence throughout their life.

In view of this situation, Mexico has signed international treaties that support the elimination of any type of discrimination and violence against women, such as “The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women”, ratified in the General Assembly of the United Nations. The Mexican State therefore has the obligation of providing the resources and the actions necessary to eliminate these forms of discrimination in the country.

Our country has committed to safeguarding the rights of Mexican women and has promulgated laws that protect their lives and their rights: the General Law of Equality between Women and Men (published in 2006), the General Law of Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence in 2007, and which was then ratified by the states that make up the Mexican Republic.

Likewise, in the state of Guanajuato, the Law of Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence was published in 2010 and, recently, in March 2013, the Law of Equality between Women and Men was signed after a debate in the different regions with women and nongovernment organizations of the state.

The General Law of Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence defines violence as: “Any action or omission, based on gender, which causes psychological, physical, patrimonial, economic, sexual harm or suffering, or death, both in the private and in the public sphere.” Izquierdo (2011: 37) defines gender violence as that “which is directed at women for the fact of being one, for being considered by their aggressors as lacking minimum rights of freedom, respect and capacity for decision”.

The United Nations proposed the Millennium Development Goals (2001), among which the elimination of different forms of discrimination against women, girls and young women is proposed, and the governments commit to “promoting gender equality and the strengthening of women as effective ways to combat poverty, hunger and disease, and of stimulating a development that is truly sustainable” (Cited in Maceira, Alva and Rayas, 2007: 60).

In countries where gender inequality has a wide gap, women and young women have serious problems to remain alive. In this sense, where there is greater gender inequality there could be forms of violence against women, such as the preference towards male sons in access to food and health, which has as consequence higher indexes of feminine mortality. A form of discrimination associated to violence is the “lethal neglect of daughters” in regions of India (Kabeer, 2006).

In patriarchal and authoritarian societies women can suffer growing episodes of violence, and even those that place their lives at risk; the vulnerability of women and young women can be greater due to the context in which they live, that is, “characterized by ignorance, poverty and isolation; the predominance of patriarchal systems that rule matrimonial relationships despotically, the absence of a father figure to provide some type of protection, the presence of a mother who imposes a degrading relationship, her transformation into a permanent victim at the mercy of a battering husband, the contempt and neglect that leads to their death which not even the sons, grown men, could stop” (Marroni, 2004: 210-211).

In the countries where rights and opportunities are denied to women, and where they are relegated to unequal roles, they have lower life expectancy, worse health and it is possible that they suffer more episodes of violence.

Violence against women is strongly linked to inequality between sexes present in societies, “in how the models of masculinity and femininity are constructed, and in the social relationships between men and women, implying the subordination of the latter” (Torres, 2004).

The effects of violence seen in social multipliers (which have to do with the impact on social relationships and on quality of life) are the intergenerational transmission of violence, the deterioration of quality of life, the erosion of social capital and, even, the lower participation in democratic processes (Morrison and Loreto, 1999).

The objective of this article is to present through a case, first, the possibilities that women have of being supported by government instances, and then, the possible difficulties they face to denounce their aggressors and to maintain their claim, because most women, particularly married ones, do not denounce, and many times we do not know and, due to gender prejudices, we can make wrong assumptions.

Violence against women in Mexico

In Mexico violence against women and girls is extended all over the country; the cases of women murdered in Ciudad Juárez are known internationally, but in addition in other states of the Republic this situation is increasing. In a study in Estado de México it was found that the group of women between 16 and 40 years of age present a higher risk (Arteaga and Valdés, 2010), that is, they are in productive and reproductive ages.

Delgadillo (2010) states that in Mexico the most frequently abused are those that work outside their homes, but also those who are immersed in a process of empowerment or who once empowered can have higher risks of suffering violence.

In Chiapas the cases of women who have been abused since they were young girls has been documented, enduring even omission and vital neglect from their parents for the simple fact of being born female, which led women and girls to death (Freyermuth, 2003).

Freyermuth (2007) carried out a study and analyzed the causes of death of indigenous women in Chiapas and observed that in several cases they had not received care for the diseases they presented and finally arrived to the hospital to die. Equally, the author identified that in the suicide cases of women, they had presented domestic violence before, which had led them to make such a decision; however, the health authorities omitted the antecedents of violence and did not record the exact causes of these and other deaths of women, including homicides. The cases that Freyermuth studied (2003 and 2007) presented the characteristic of dead women who had allegedly died from childbirth had been beaten on numerous occasions by their husbands and mothers-in-law, in addition to many of them having been denied access to medical treatment and food.

In Michoacán, indigenous women show high rates of violence, compared to mestizo women, although the official statistics do not evidence that fact, probably because women from native peoples did not respond adequately the questionnaires that the INEGI applied, due to monolingualism, distrust or other causes (Huacuz and Rosas, 2011). However, the Endireh shows the following alarming data:

15 % of indigenous women said that their spouse gets upset over the way they educate their children.

4 % of them said that their spouse gets upset if she gets pregnant.

12 % of them are threatened because they do not fulfill their role as mothers.

31 % of them said their spouse gets upset if she does not obey.

12 % of them manifested that their spouse gets upset if they do not want to have sexual relations.

34.1 % of the indigenous women affirmed that their spouse stops talking to her when he gets angry.

13 % of them are yelled at and insulted.

5.9 % of them are thrown things and beaten.

5 % of them get locked up.

16 % of them live with fear over the actions of their spouse.

7 % of them have been kicked.

13 % have been beaten with an object or with the hand.

14 % have been forced to have sexual relations.

This is what the official statistics report in Michoacán, in relation with the indigenous women, but in interviews they mention that these percentages are underestimated and that the violence that they suffer begins since they are very young in the hands of their family members and continues when they are married (Huacuz and Rosas, 2011).

Violence against women in the country is alarming and increasing. Gender violence is not exclusive only of certain social classes; it goes through social class, ethnicity and level of schooling. That is, it is a phenomenon that affects all women in the country in general, even those who state that they have never been a victim of violence since symbolic violence persists in all the social levels and public and private institutions.

Violence against women in the state of Guanajuato

In the recent Endireh (2016) survey, the prevalence of violence against women older than 15 years was measured, that is, what they have endured throughout their life. The figures for the state of Guanajuato are the following: in 2016 it was 63.2o%; in 2011, 56.2 %; and in 2006, 58.8%.

The same as at the national level, in 2011 it seems that this violence index decreased, but it rose again in 2016. That is, six out of ten women older than 15 years in the state of Guanajuato have endured some type of violence throughout their life. In addition, this increase in violence against women is related to the increase of femicides in the state.

The violence can originate in diverse contexts: in the family, in school and in public or community spaces. At the community level, 40 % of the women who answered the National Survey on the Dynamics of the Household Relationships (Endireh, 2006) stated having suffered some type of violence. Of this group, 31 % suffered sexual abuse in their communities and the rest (69 %) felt intimidated in the community sphere; from this the vulnerability of women in our country. These figures are slightly lower in the state of Guanajuato, where 35 % of the women interviewed stated having endured violence within the community sphere. This figure is very important since it reflects that women in the state do not feel safe in their communities and it is very likely that they do not want or do not know who to denounce for violent acts which they are going through or have undergone. A third part of those who state they have suffered violence in community spheres have endured episodes of sexual abuse.

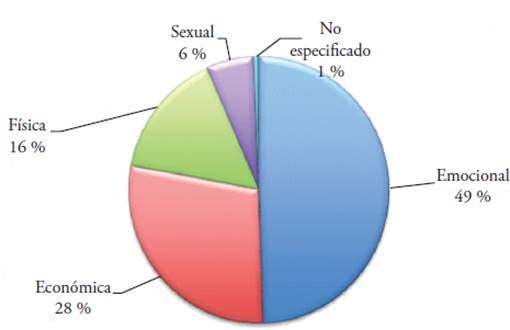

The statistics on violence against women in the state continue to be alarming. The National Institute of Geography and Information (Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática, INEGI) through the ENDIREH 2011 informed that 24 % of the women from Guanajuato of 15 years and older have suffered some type of violence from their spouse in the last 12 months, while 28 % of the married women or in a relationship said that in the last 12 months their spouse had exerted violence against them. Next, the types of violence are shown. It should be clarified that the percentages do not add up to 100 %, given that the women reported more than one type of violence (Figure 1).

Source: authors’ elaboration based on the Endireh, 2011.

Figure 1 Percentage of women of 15 years or older in Guanajuato, according to types of violence against them by their partner experienced in the last twelve months.

Castro (2012) mentions that what surveys measure is the situational violence of the couple, where there are violent episodes against women, without reaching extreme violence, as it happens in the cases of intimate terrorism1. That is why less incidents of physical violence against women are reported.

Where is violence denounced?

It is alarming that most of the women who have suffered violence do not resort to any agency, at least not the ones INEGI present; the one they turn to most is the Public Prosecution Office and then the municipal DIF. The results from the Endireh (2011) do not state or in any case the data were not collected about whether women go to any NGO to request support (Table 1).

Table 1 Percentage of women 15 years or older who experienced physical or sexual violence throughout their relationship with their last partner, per support agency they have resorted to.

| Instancia de ayuda | Total | Porcentajes | Casadas o unidas | Alguna vez unidas | Nunca unidas |

| Estados Unidos Mexicanos | 6 362 473 | ||||

| DIF | 596 331 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 12.5 | 2.1 |

| Instituto de la Mujer | 178 154 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| Ministerio Público | 730 661 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 16.4 | 3.5 |

| Presidencia municipal o delegación | 331 114 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 6.9 | 2.1 |

| La Policía | 451 755 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 9.5 | 1.9 |

| Otra autoridad | 169 046 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| Familiares | 58 847 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15.5 |

| Ninguno | 4 412 257 | 69.3 | 73.0 | 64.6 | 70.7 |

| No especificado | 142 628 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 6.3 |

Source: authors’ elaboration based on the Endireh, 2011.

Note: the data presented are general, not by state.

Although women do resort to the police, it is a relatively low percentage and in addition there is no guarantee of help from them, because they are not trained in women’s rights or in gender perspective to be able to attend to the problem adequately.

In the municipality of Salvatierra, Guanajuato, during a visit to the public prosecutor agency, it could be verified that the person in charge minimizes the words of women, does not attend their complaints professionally, and the cases are widely commented as gossip. The agent referred to the case of a young woman who had been raped as “another little raped one”, with which we could think that she doesn’t believe what the women denounce and she minimizes the facts. Sexual violence in itself has grave consequences, such as depression, anxiety disorders, nervous problems, anguish, appetite problems, among others (Luna, 2009), but the revictimization of victims by the legal apparatus should also be added, from those who should provide protection and safety. Luna (2009) also states that it is difficult for women to denounce, particularly their spouses, and all the more if they are women who have suffered sexual violence from their spouses “… especially because for those affected this implies proving that they did not consent to sexual aggression, whatever its nature may be” (Luna, 2009, p. 281).

The women who have never been in a relationship turn mostly to support from family members (15.5 %), in contrast with the married women or in a relationship, or those who once were.

As is seen in the previous table, the main government institutions to which women resort seeking help or searching for justice are: the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the municipal DIF, the police, the Municipal Presidency or the delegation and, finally, the Women’s Institute.

Thus, the importance of having an accurate understanding of the government offices that offer or could offer support to women who are experiencing a life with violence stands out, but also those that may support them in other areas of their lives, such as education and economy, among others.

Likewise, it is imperative that the government agencies to which women resort have more gender sensitization or that they incorporate this sensitivity to their procedures. Therefore, the following is needed:

Building alliances with civil society organizations to articulate objectives and actions to support women. The problem is that in some regions of Guanajuato there are no feminist NGOs that defend women’s rights.

Generating information systems and their knowledge among the different government agencies.

Making known to women the agencies that could support them in cases of violence.

The different levels of government should have among their objectives the shortening of gender gaps, which are defined as: “the differences in conditions and treatment between men and women, which lead to inequality in the distribution of costs and benefits, access to services and to resources, in the ability to control, and in participation and intervention in decision making” (Massolo, 2004: 18).

Materials and methods

In order to research and analyze the actions of the municipal government agencies, eight in-depth interviews were performed with rural women from different localities in the municipality of Salvatierra, Guanajuato.

The interview with a rural woman is presented, since she did carry out numerous actions to end a relationship that was increasingly more violent; we will call her María to protect her identity. We take this case for this reason because, in contrast with other women, she did denounce repeatedly to various agencies until she was able to separate from her violent husband. The quantitative data of the Endireh 2006, 2011 and 2016 were very important. However, the contribution of the qualitative methodology for the construction of this study was fundamental, and particularly the feminist approach, since it reveals “that the subject of knowledge is a particular historical individual, whose body, interests, emotions and reason are constituted by her concrete historical context, and they are especially relevant …” (Guzmán and Pérez, 2005: 643). That is, from the perception of this woman we can understand the situations and motivations that could lead her to not denouncing the violence exerted on her or, once the claim has been made, to forgive the aggressor.

Results and discussion

María is a 38-year-old woman, with two daughters and one son. She does not have permanent employment, yet she sells snacks and completes her income with what she receives from the government program used to combat poverty. She states that she was living relatively well with her husband until he started migrating to the United States. The same as many other residents of Guanajato, he would go for a long season and then return for some time to his town. The second time that he went and returned the problems began.

Well, when he was here he would get angry about everything, he didn’t know how to do anything, he would yell at me, call me things, and he would also yell at the children and that was the way it was the last time he came; then he went back and the most recent time he returned it got worse.

She knew that he had other women, she complained about it many times and the beating began; also, her husband accused her of being crazy:

He hit me (sobbing), he kicked at me and hit me on the mouth; in front of the children he would yell at me many things: stupid, lazy, you don’t know how to do anything. I didn’t tell any of this to my mother because I didn’t want her to know, until one day the girls went and told her: Grandma, my father hit my mother really badly. My mother told me: why didn’t you tell me anything before? Why do you stay quiet? How can we help you?

The same as many married women who are battered by their spouses, she did not resort to asking for help from her family. Married women or who are in a relationship are the ones who request help the least; not only from their family, but they also do not resort to other instances. According to the Endireh (2011), none of the women surveyed resorted to requesting help from their family and 8.5 % resorted to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, while 7.7 % went to DIF (System for the Integral Development of Family, Sistema para el Desarrollo Integral de la Familia). The percentages are similar to those found among the women who had once been married or in a relationship. However, as will be seen later, the government agencies did not help the women who suffer violence either.

María decided not to withstand the abuse anymore; in this case she only talks about the hitting, but generally the violence that women may suffer is of all types: psychological, physical, sexual, economic. She states that her husband beat her and cheated on her with other women; that they had a series of fights and he told her she didn’t know how to do anything. Also, she states that he raped her and she denounced the fact to the authorities: “Yes, I also denounced him and they did some studies with a doctor, who told me I was fine, that I didn’t have any signs of violence”; in addition, they doubted her word. Torres (2004) mentions that one of the main obstacles that government organizations have are prejudices and traditional gender notions that permeate the application of laws because it is believed that wives cannot be raped by their husbands (or by other people because it is thought that it is the women who “seduce” the men or “allow” the rape).

Finally, after fights, insults and blows, although she minimizes it because she states that “he only hit me about three times, but in the most recent it was when he hit me the worst,” then after that time she decided to inform her family that she was going to ask for a divorce; they told her to think about it, but that if she wanted to divorce, she should, that they would support her. She went to the Public Prosecutor’s Office to denounce him because, in addition to the physical violence, he stopped giving her child support. However, despite the demand for child support, the husband did not comply. She went to sue him and in the Prosecutor’s Office they told her that he could stay in prison or pay a fine of six thousand pesos. With this situation the pressure started for her to remove her claim, both from her husband and from her relatives. She did not.

In other studies carried out (Huacuz and Rosas, 2011), the public security agents complain that they arrest the abusing men, but then it is the women themselves who lift the claim and forgive them and set them free. They state that facing this situation they do not pay much attention to the denunciations. The problem is that the security agents and the Public Prosecutors are not aware of all the pressure that the women experience, both from their own families and from their husband’s or partner’s. It is difficult to withstand the pressure and threats, and many of them end up eliminating the claim.

In the case of María, in addition to the pressure for her to lift the claim, she had pressure from the husband’s relatives when she manifested her wish to divorce him:

Her father was angry, and he said: well, think about it because if you get divorced I will kick you out of the house, he said, and I told him: well, do whatever you want, I am getting divorced because what he is doing is a mockery of me and my children (crying). And he answered: you divorce and then you have to leave right away, with your whole family.

She, worried about the situation, decides to consult with her lawyer, who informs her that it is not possible to be kicked out of her house. These and other threats toward women who decide to end a situation of violence, as is the case of María, make it very difficult for them to dare to finish with it; socially, they are seen as people who change their opinion easily, who “like to be hit”, and this difficult situation is not understood; this is why denunciations are minimized and they are not listened to. Likewise, the women are made responsible about the situation of violence that they experience at the hand of their spouses.

On the other hand, María said in the Public Prosecutor’s Office that she wanted to divorce, but the agents asked her why if the husband was saying that he was happy with her. In this case, the husband didn’t want to divorce. As Izquierdo (2011) states, the domestic infrastructure makes it easy for men to perform their paid activities, to have availability for work and mobility, and it is the wives who are socially responsible of domestic tasks; therefore, María’s husband didn’t want to get a divorce because he would lose the domestic support from his wife.

In the case we are analyzing we can state that patriarchal terrorism was experienced (and is surely still being experienced). María is not only threatened by her husband, father-in-law and other relatives, but her husband is also helped by the legal system that should have protected her. Even in face of the beating and humiliation to which she was subjected.

Lagarde (2012) states that there is government discrimination in treatment toward women, since when they go to request help and protection from the institutions of the Mexican State they are pressured to desist from their claims.

When María requested help to obtain child support, it was denied, and when she went to the municipal DIF office they did not believe her about the abuse by her husband, as her testimony clearly indicates:

The lawyer said: but you are the one who wants the divorce, not him. Then, since he says that he works in the field and sometimes he works and sometimes not, that he will only be able to give you two hundred pesos per week, if you agree, that’s good, if not then you will have figure it out yourself.

I had gone to DIF some years before and there they also asked me why I didn’t have proof that he had been with someone else, and that they could not do anything. They only told me: the thing is that you only say that he is going out with another woman and that he doesn’t give you money, and abuses you, but we want proof. And I even told them: what do you want me to do, to come here with the bruises, or what? And he answered that not so much, but that they needed proof.

Without proof to get help from DIF, without support from the Public Prosecutor’s, María decides to go to a private lawyer, who had supported a cousin of hers in a similar case, and to file for the divorce.

Lagarde (2012) states that the social importance of gender violence is dismissed with the arguments that society in general is violent and that there is more violence against men, that there are more deaths of men than of women. In addition, she states that there is an under-registry of the cases of violence against women, but also that there are few denunciations, particularly because the problem is minimized by the misogynistic culture present in the institutions and “due to the legal exclusion of women, and because the laws and the legal structure have been used against women as instruments of gender domination” (Lagarde, 2012:194).

After the divorce, the ex-husband leaves the family household, but he doesn’t give any child support for the daughters and son. María and the children survive with the support from the government program against poverty and with a small business of selling food from their house door.

In addition to economic scarcity, she must face the complaints from her eldest son who does not agree with her divorce, in addition to demanding part of what the government grants María because his father no longer gives him money.

He already knew everything, but he didn’t say anything (the son). Only one time that his father didn’t want to give him money, he said; see, Ma? It’s your fault that my Pa doesn’t give me money, and I tell him, Bah! Why would I be to blame? Because you divorced him, it’s your fault.

The son has refused to go to doctor’s appointments to the community health center, so he has lost the government scholarship and states that his mother receives a lot of money and that that money should be his. The daughters, in turn, since they saw the beatings that the father gave his mother, agreed with the separation. Although the father beat the mother, humiliated her and didn’t give her money, the son makes an alliance with him.

On the other hand, in addition to having been through situations of violence from her ex-husband and from poverty, María is currently harassed by friends of her ex-husband, who when seeing her free chase her systematically to obtain sexual favors from her.

Many women are not only mistreated in the heart of their families, but in the community and social sphere they suffer aggressions and, in fact, even in the work sphere; these forms of violence, Izquierdo calls the syndrome of the abused woman (Izquierdo, 2011).

In the social construction there are relationships, practices and institutions that generate and preserve the masculine power and privileges on the inequality and subordination of women (Lagarde, 2012). Therefore, it is confirmed that the culture effectively frames, names and gives sense, legitimizes, translates and reproduces, in part, this social organization. It does not generate it, although it acts dialectically with society. Education is only one dimension of culture. Although the educational contents are transformed and education has as content generic democracy and human rights, if sexuality, the role and the position of genders are not modified in economic relationships, social structures and institutions, relationships in all social spheres, social and political participation of women, laws and legal processes, violence against women will not be eliminated. And, naturally, if the gender condition of men is not modified radically, violence against women will continue (Lagarde, 2012: 201).

Conclusions

María’s situation, who was able to escape violence from her husband, exemplifies the difficulties that women undergo when they denounce these situations. One of the constant feminist preoccupations is that the strategic needs of women are addressed, that is, those that give them the power to decide over their lives, and which allow them to move away from this sort of problem. However, María only studied primary school, does not have a permanent job, and does not have social security, and is part of the statistics of feminine poverty, although in spite of this she was able to leave this situation.

The support that she received from municipal authorities was practically non-existent, because although they took her declaration in the Public Prosecutor’s Office and fined her husband, she didn’t have any other support and was pressured to desist from the divorce. In the municipal DIF they did not believe her claims and asked for proof to do something in her favor. Therefore, initial statistics of complaints shouldn’t surprise, where it is shown that there are few denunciations of violence.

Her case, as that of other women in her town, was only recorded by the Health Center as a statistic, but it was not channeled to a competent agency to receive support, although there is the question of whether there are truly competent official institutions in the study region. If, as the director of the health center states, as health workers they are obligated to ask women who go for consult whether they have been victims of violence, many of them deny it despite the bruises. The director only records it, and in case of sexual violence towards minors, must denounce to the Public Prosecutor’s Office because the law mandates it, but she doesn’t know what happens with the cases. In the health center they are limited to only healing the physical injuries of the women and the diseases that derive from the violence, such as those of sexual origin. Sometimes, those who accept it are sent to the psychologist in the municipal township, but many times the health centers have been surpassed by the large number of women they have to treat.

In this case, and in many others, they force or attempt to force the women to not denounce or to lift the claims that they have made; there are social, institutional and family pressures that can contribute to the impunity in the cases of violence, and this impunity can lead to worse cases of femicide violence.

Gender violence against women has to do with their rights, recognized or not. In this case the violence is normalized and the right to have a life free from it is not recognized, including the right to life, since violence grows and can reach the assassination of women. For rights to be exercised, such as those mentioned, the government institutions must be capable to formulate government actions that tend to provide the poorest and most vulnerable people (as many women are), access to food, shelter, work, healthcare, education, mobility and expression, and protection against harm and oppression; and women like María have not or have hardly had this, because she and her children were denied money for food, she doesn’t have work, and she doesn’t have any kind of protection from the State.

If poor women, a group excluded from many rights, do not have access to food, work and health services, then they do not have the adequate conditions for their lives to be protected: they are lives that can be discarded because those who impose the rules of the game have excluded them. They are lives on the margins and lives that are easily discarded.

Within the group of the poor, poor women have a life that is even more precarious simply as a result of being women. Therefore, being a poor woman means almost belonging to the group of “non-people”, but being poor, women and indigenous is even more precarious and dangerous for the life of such women: they “vanish”, as Freyermuth (2003) describes in his book Mujeres de Humo [Smoke women].

In this case, being a rural woman, she is expected to have even less tools to leave this situation of violence, but in her case she did have a family support network that was very important for her to make a decision and be able to leave the violent husband. In the rural communities of the region there are no institutions that support this type of process, so this case takes on particular relevance.

Like other researchers of the theme, we declare that government institutions still present grave anomalies to take care of women in situations of violence. First, despite the laws passed, women are still attended with a focus of domestic violence and sexual crimes, and not with the focus of gender equality and human rights; second, most judges do not understand or are not interested in the new legislation; women’s institutes do not record systematically the number of machista violence against women, in addition to their actions being quite limited; in the case of the National Commission of Human Rights (Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, CNDH), although it has an area of gender violence, in some cases it has been undermined and behaves ambiguously in face of the denounced men; also, the human rights commissions in the states have not taken on gender violence cases as belonging to their agencies or they assume them in a very precarious way.

Despite the structural considerations about violence, which are in the interest of the government part where women are attended as individual beings, gender violence against women is part of the established social order, which is why this phenomenon many times goes unnoticed even by women themselves.

Finally, we can state that even though laws were passed that attempt to protect the lives of women, such as the Law of Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence, and the Law of Equality between Women and Men in the State of Guanajuato (the latter approved in 2013), those who are in charge of applying the laws such as the police, agents of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, judges, stem first from the idea that women lie in these situations. They have very traditionalist ideas of gender roles, which make it difficult to think of women as autonomous beings who are holders of rights. Thus, even with the advancement of laws, the prevailing traditionalist and macho mentality makes it difficult for women who are attempting to move away from situations of violence. Some of them even lack social networks to support them, which presents an additional difficulty.

The creation in the study region of a center for attention to women’s rights is essential, to accompany them when facing the institutions that they resort to in order to denounce violent facts and which can monitor that authorities are trained in women’s rights, respect them, make them valid, but above all, do their job and impart justice.

REFERENCES

Arteaga, Nelson, y Jimena Valdés. 2010. ¿Qué hay detrás de los feminicidios? Una lectura sobre redes sociales y culturales y la construcción de la subjetividad. In: Arteaga Botello, Nelson (coord). Por eso la maté… Una aproximación sociocultural a la violencia contra las mujeres. México: Porrúa y UAEM. [ Links ]

Castro, Roberto. 2012. Problemas conceptuales en el estudio de la violencia de género. Controversias y debates a tomar en cuenta. In: Baca, Norma y Graciela Vélez (coords). Violencia, género y la persistencia de desigualdad en el estado de México. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Mnemosyne Ed. [ Links ]

Delgadillo, Leonor Guadalupe. 2010. La violencia contra las mujeres. Dimensionando el problema. In: Arteaga, Nelson (coord). Por eso la maté… Una aproximación sociocultural a la violencia contra las mujeres. México: Porrúa y UAEM. [ Links ]

Freyermuth, Graciela. 2003. Las mujeres de humo. Morir en Chenaló. Género, etnia y generación, factores constitutivos del riesgo durante la maternidad. México: CIESAS, Instituto Nacional de las mujeres, Comité por una maternidad voluntaria y sin riesgos en Chiapas y Porrúa editores. [ Links ]

Freyermuth, Graciela. 2007. Realidad y disimulo: complicidad e indiferencia social en Chiapas frente a la muerte femenina. In: Olivera, Mercedes (coord). Violencia feminicida en Chiapas. Razones visibles y ocultas de nuestras luchas, resistencias y rebeldías. México: UNICACH. [ Links ]

Guzmán, Maricela, y Augusto Pérez. 2005. Epistemología feminista: hacia una reconciliación política. In: Blázquez, Norma y Javier Flores (eds). Ciencia, tecnología y género. México: UNAM, Centro de Investigaciones interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades. [ Links ]

Huacuz, Guadalupe, y Rocío Rosas. 2011. Violencia de género y mujeres indígenas en el Estado de Michoacán. In: Rosas, Rocío (coord). El camino y la voz. Visiones y perspectivas de la situación actual de Michoacán: género, política, arte y literatura. México: Universidad de Guanajuato, Altres Costa-Amic Editores. [ Links ]

Izquierdo, María de Jesús. 2011. La estructura social como facilitadora del maltrato. In: Huacuz, Guadalupe (coord). La bifurcación del caos. Reflexiones interdisciplinarias sobre violencia falocéntrica. México: UAM-Xochimilco. [ Links ]

Kabeer, Naila. 2006. Lugar preponderante del género en la erradicación de la pobreza y las metas del desarrollo del milenio. México: Plaza y Valdés, IDRC. [ Links ]

Lagarde, Marcela. 2012. El feminismo en mi vida. Hitos, claves y utopías. México: Gobierno del Distrito Federal e Instituto de las Mujeres del Distrito Federal. [ Links ]

Luna-Santos, Silvia. 2009. Violencia sexual contra las mujeres, infligida por la pareja. In: Gutiérrez, Miriam. La violencia sexual: un problema internacional. Contextos socioculturales. México: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [ Links ]

Maceira, Luz, Raquel Alva, y Lucía Rayas. 2007. Elementos para el análisis de los proceso de institucionalización de la perspectiva de género: una guía. México: El Colegio de México, Programa Interdisciplinario de Estudios de la Mujer. [ Links ]

Marroni, María da Gloria. 2004. Violencia de género y experiencias migratorias. La percepción de los migrantes y sus familiares en las comunidades rurales de origen. In: Torres, Marta (comp). Violencia contra las mujeres en contextos urbanos y rurales. México: El Colegio de México, Programa Interdisciplinario de Estudios de Género. [ Links ]

Massolo, Alejandra. 2004. El gobierno municipal y la equidad de género. In: Barrera, Dalia, Alejandra Massolo e Irma Aguirre. Guía para la equidad de género en el municipio. México: GIMTRAP, Indesol. [ Links ]

Morrison, Adrew, y María Loreto. 1999. El costo del silencio: violencia doméstica en las Américas. Washington: BID. [ Links ]

Torres, Marta (comp). 2004. Violencia contra las mujeres en contextos urbanos y rurales. México: El Colegio de México, Programa Interdisciplinario de Estudios de Género . [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (ENDIREH). 2006. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/Proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/endireh/Default.aspx [ Links ]

Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (ENDIREH). 2011. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/Proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/endireh/Default.aspx [ Links ]

Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (ENDIREH). 2016. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/Proyectos/encuestas/hogares/especiales/endireh/Default.aspx [ Links ]

Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a una Vida Libre de Violencia. Publicada en el Diario oficial de la Federación, 1 de febrero de 2007. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGAMVLV.pdf [ Links ]

1 Castro (2012) defines intimate terrorism as the shots, attempts to choke, attacks with sharp arms, or tying up (they could be seized by their own intimate partner), to which women are subjected.

Received: July 2015; Accepted: August 2017

texto en

texto en