Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versão impressa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.15 no.4 Texcoco Out./Dez. 2018

Articles

Productive Reconversion to Oil Palm in the Tulijá Valley, Chiapas, Mexico: Impact differentiated by gender

1Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo (yyoal@hotmail.com), (emzapata@colpos.mx),

2El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad San Cristóbal (anazar@ecosur.mx).

3 Grupo Interdisciplinario sobre Mujer, Trabajo y Pobreza A. C. (suarezblanca@yahoo.com.mx).

Starting from the premise that points to global processes impacting differentially in the local scope and that their implications and responses are related to particularities in each territory, this study attempts to explain the impact differentiated by gender of the public policy, framed within global economic processes that drive the productive reconversion to palm oil in small productive units of three indigenous localities in the Tulijá Valley, Chiapas, Mexico. The information presented was collected and analyzed through a mixed research approach, using as fundamental tools the survey and the semi-structured interview. Initially the local context is analyzed, finding asymmetrical gender relationships at the family and community level. Then, the expression of the public policy of productive reconversion to oil palm in the communities is described, especially since the transformation of economic activities, showing its impact on the local provision of foods and the monetarization of the family income. Finally, the differentiated impact by gender is identified finding that the productive reconversion to oil palm entails greater disadvantages for women due to unequal gender relationships.

Key words: biofuels; food crisis; rural development; neoliberal globalization; public policies; gender relationships.

A partir de la premisa que señala que los procesos globales impactan diferencialmente en el ámbito local y que sus implicaciones y respuestas se relacionan con las particularidades de cada territorio, este trabajo pretende dar cuenta del impacto genéricamente diferenciado que ha tenido la política pública, enmarcada en procesos económicos globales, que impulsa la reconversión productiva a palma de aceite en las pequeñas unidades productivas pertenecientes a tres localidades indígenas del Valle del Tulijá, Chiapas, México. La información presentada se recolectó y analizó a través de un enfoque mixto de investigación, utilizando la encuesta y la entrevista semiestructurada como herramientas fundamentales. Inicialmente se analiza el contexto local, encontrando asimétricas relaciones de género a nivel familiar y comunitario. Posteriormente, se describe la expresión de la política pública de reconversión productiva a palma de aceite en las comunidades, especialmente a partir de la transformación de las actividades económicas, mostrando su incidencia sobre la provisión local de alimentos y la monetarización del ingreso familiar. Finalmente se identifica el impacto diferenciado por género encontrando que, con base en las desiguales relaciones de género, la reconversión productiva a palma de aceite conlleva mayores desventajas para las mujeres.

Palabras clave: biocombustibles; crisis alimentaria; desarrollo rural; globalización neoliberal; políticas públicas; relaciones de género

Introduction

To speak about productive reconversion is to refer to a social process determined historically, in which productive aspects are influenced by different external changes (Santacruz, Morales and Palacio, 2012) that manifest consequences, not always favorable for most of the population (Fritscher, 1990). From the perspective of public policies, productive reconversion is conceived as a strategy for competitiveness of the agriculture and livestock sector, a “process through which productivity is increased, value is added, production is diversified, or a change in crops is made towards those with higher profitability” (Arias, Olórtegui and Salas, 2007:9).

However, the process of productive reconversion in agriculture is also related to the dependency on foods and inputs and with recent food crises. In the local scope, the variety and availability of foods decreases among peasant families, whether because of the increase in prices of foods and inputs to grow them, or due to the substitution of cultivation of foods for self-consumption and local commerce by the production of energetics or inputs that respond to the needs of the global market (Chauvet and González, 2013).

On the other hand, international worries around economic, energetic and environmental security guide the countries to consider new energetic alternatives, such as the use of biofuels. In face of this new demand, peripheral countries with favorable climate and agronomic conditions have encouraged, stemming from productive reconversion public policies, the growth of plantations directed at the supply of raw materials for the production of biodiesels and bioethanol, such as soy, oil palm or sugarcane (German et al., 2011; HLPE, 2013), despite the strong pressure that this exerts at the local level on the use of resources such as land and water (Friedrich, 2014).

Oil palm cultivation has increased to the degree that it has been considered by some governments of under-industrialized countries as a path to earn currency from its export. For enterprises it is a profitable option, mainly because of the low cost of rent or sale of lands and workforce, the absence of effective environmental controls, the financial support from multilateral organizations like the World Bank, and the growing international market. Presently, transnational industrial companies such as Unilever, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Kenkel, Cognis and Cargill dominate the global market of oil palm (PRODESIS, 2005).

Within this context, small groups of producers are encouraged, by the State and corporations of different origins, to restructure their productive practices based on the promotion of crops, such as oil palm, directed at the production of biofuels. Paradoxically, in contrast to the discourse of sustainable development that justifies this, the expansion of this crop has proven that it increases social and environmental contradictions, accentuating inequalities and deteriorating natural resources (Fletes et al., 2013).

In Chiapas, the policies of reconversion to oil palm monocrop, whose commercial destination is primarily the food and biofuel industry, has been promoted from the state, national and international sector, through different modalities of support (technical, financial and infrastructure) in the regions of Coast, Soconusco and Rainforest, in detriment of supports for the production of other crops such as maize and bean, thus forcing the peasant and indigenous populations to reconvert their traditional production (Chauvet and González, 2013; Fletes et al., 2013).

International cooperation projects, such as the Program for Integrated and Sustainable Development (Programa de Desarrollo Sostenible Integrado y Sustentable, PRODESIS) in cooperation with the European Union, promote the productive reconversion to oil palm in the Rainforest region of Chiapas, conceiving it as good business due to the high global demand for oil palm, the favorable climatological conditions, the availability of lands and the cooperation of the government with resources (PRODESIS, 2005), with the latter being a fundamental element, although palm plantations would not be profitable without the different government subsidies (Castro, 2009).

In its turn, the Mesoamerican Biofuel Program (Programa Mesoamericano de Biocombustibles), which belongs to the Mesoamerican Project, is created as a strategy to implement decentralized schemes of energetic production, including the installation of biofuel plants and the conformation of a Middle American Network of Research and Development in Biofuels (Proyecto Mesoamérica, 2013). In the case of Mexico, for the supply of raw materials, the productive reconversion program that promotes the cultivation of Jatropha curcas and oil palm was established for the elaboration of biodiesel (Chauvet and González, 2013).

The promotion of the oil palm cultivation in Mexico began during the six-year period of 1982-1988 in the Chiapas municipalities that belong to the Soconusco region. In the decade of the 1990s the cultivation was implemented in the Rainforest region, expanding in a few years to other regions of the state. Until today, the oil palm plantations are located in 52 municipalities that belong to Chiapas, Campeche, Tabasco and Veracruz. The greatest impulse to the crop has taken place during the last five years; at the end of 2016, official figures reported a cultivated surface of 90 118 hectares, of which close to half are located in Chiapas (Figure 1) (SIAP, 2017).

Source: authorselaboration with data from the Agiculture, Livestock and Fishing Information Service (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, SIAP, 2017).

Figure 1 Surface planted with oil palm in Mexico and Chiapas. Period 1983-2016.

One of the territories that have historically been object of the policies of productive reconversion is the Tulijá Valley. Changing from forest exploitation to extensive livestock production, the overexploited lands, now ejidos and small properties, have been integrated to the production of oil palm since the decade of the 1990s (Nazar, Salvatierra and Zapata, 2008). From the government support given to this crop during the first years of this century, the surface cultivated with oil palm in this region has increased 407 %, with 1 454.5 hectares counted in the year 2012 (SIAP, 2017). In the communities that are mostly Choles and Tzeltales that make up the Valley, the crop is grown in small peasant units of low competitiveness, using mainly family workforce (Morales and Salvatierra, 2012).

The government support to the oil palm crop in the small plots finds among its justifications that it is implemented in marginal lands of low production or in lands abandoned by livestock. However, the low supervision and consulting in these new crops places at risk the survival of the small-scale productive units. Rather than reconverting productively the lands that are marginal and unproductive, from the entrepreneurial and government optic, peasants are forced to reconvert the land that has been essential to their survival (Nazar, Salvatierra and Zapata, 2008; Chauvet and González, 2013; Fletes et al., 2013).

The disadvantages and the risks of reconversion to crops with energetic aims for the peasants have been denounced even by multilateral organizations like the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (2012), conceiving it as a strategy which, by promoting monoculture at a large scale, threatens biodiversity and soil fertility, affecting negatively the population of the farmland. It decreases its ability to guarantee foods and their means of subsistence, placing their resources at risk: “the biofuel programs can give place to property concentration that could expropriate lands from the poorest farmers and exacerbate their poverty” (BM, FAO and FIDA, 2012: 586).

These new productive processes increase the disadvantageous position of peasants and tend to affect differentially inside the societies, among other things, because: 1) they demand a large amount of resources (land, agrichemicals, water, etc.) to which it is difficult for all peasants to have access to, especially women; 2) they are highly dependent on credits and subsidies which are generally limited and insufficient for peasants, particularly for women peasants who have less titles or property rights; and 3) the use of land plots, on which women closely depend for the social reproduction of their families (Rossi and Lambrou, 2008).

The evaluation of the potential effects of productive reconversion policies to oil palm should analyze, from a gender perspective, the behaviors and social interactions that these government actions entail. In this sense, in light of the policy of productive reconversion to oil palm, promoted as a government strategy for rural development that seeks the integration of small-scale productive units to the market, the cultivation of oil palm has been fostered in the Tulijá Valley. Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyze from a gender perspective, what are the implications that this public policy has on the survival and reproduction of inhabitants of Tulijá Valley, Chiapas.

Methodology

Various censuses and studies have accounted for the growing productive reconversion to oil palm in the state of Chiapas (Nazar et al., 2008; Castro, 2009; Santacruz et al., 2012; Fletes et al., 2013; Chauvet and González, 2013, among others). Salto de Agua is one of the municipalities in the state where the oil palm crop has been established in small peasant and indigenous plantations. Official figures reported an increase greater than 400 % of the surface sown in the municipality during the first decade of this century (SIAP, 2017).

For this study, three indigenous localities that belong to the municipalities of Salto de Agua were selected: 1) Río Tulijá. It is a Tzeltal community, located on the federal road that communicates the cities of Palenque and Ocosingo. In this locality, 78% of the total families plants oil palm and began the productive reconversion in 1996; 2) El Tortuguero 2ª Sección. It is a Chol locality located on the banks of the Tulijá River. Oil palm cultivation began in 1998 and is carried out by 55 % of the families; and 3) Las Vegas. It is located on the banks of the Tulijá River, its population belongs to the Chol ethnic group and it has been reported that half of the families in this location plant oil palm, having begun the process of productive reconversion in 2003.

The methodology used was mixed. It included quantitative and qualitative methods through a two-stage model. The first contemplated the quantitative aspect of the research through the use of the survey. A specific structured questionnaire was designed for this study with the objective of gathering information that allowed understanding the local context and identifying transformations in the socioeconomic and gender relationships derived from the productive reconversion. During the second stage, a qualitative approach was carried out through interviews. The semi-structured interview was used to delve into the key aspects of the survey, at the same time that it allowed its validation. The objective was to understand the repercussions of the process of productive reconversion to oil palm in the life of the women interviewed, their families and community, based on their opinions and personal experiences. The two-stage model allowed for the information obtained in the first to be validated by the second, giving better support and depth to the results.

The semi-structured interviews were directed towards women heads of households or housewives that belong to the group of families that plant oil palm in the localities of the study. Each interview had the objective of deepening into the opinion, experience, participation and expectations of informants about productive reconversion to oil palm carried out in their plots. In total, 14 women were interviewed, selected based on their availability to be interviewed; the size of the sample responded to the saturation of categories in each locality. It was found that the information obtained from the interviews complemented the data obtained previously through surveys, although without offering novel information. By being associated to the questions of the questionnaire, the information obtained from the interview allowed presenting it as complement to the results obtained by the survey, seeking with this to overcome some “blind spots” of the questionnaire, such as the responses obtained based on normative terms or “ought to” of women informants.

The size of the localities selected allowed performing a door-to-door census where all the families were contemplated, including those that cultivate oil palm and those who do not. This tool was applied to the mothers or heads of households in all the domestic groups of the three localities, gathering in total 189 families interviewed, which represented a participation rate of 95 % (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of questionnaires applied and participation rate per locality.

| Localidad | Total de familias identificadas |

Número de familias encuestadas |

Número de familias que no participaron en el estudio |

Tasa de participación (%) |

| Río Tulijá | 108 | 104 | 4 | 96.3 |

| Las Vegas | 35 | 32 | 3 | 91.4 |

| Tortuguero 2a Sección | 56 | 53 | 3 | 94.6 |

| Total | 199 | 189 | 10 | 94.9 |

Source: authors' elaboration with field work data, 2014.

The analysis of information gathered through the survey had an exploratory, descriptive and relational reach. The statistical program for social sciences, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), was used, analyzing different distributions and intersection of variables. The exploration of data contemplated measures of central trend and dispersion, primarily the arithmetic mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test of independence was used (X²) with a confidence level of 95 %, to identify the existence or not of association between socioeconomic variables, seeking to relate the sex of the population and other categorical variables like the condition of literacy, educational level, bilingualism, occupation, ownership of resources, and availability of free time. The data allowed comparing the condition of planting palm or not with some socioeconomic variables, and identifying some statistical association or relationship that indicates differences in the socioeconomic levels between the families that plant palm in comparison with those that do not.

The gender relations analysis is considered as a critical element to recognize the power relations between men and women (Tepichín, Tinat and Gutiérrez, 2010) and to identify the way in which the rights, responsibilities and identities are defined (De la Cruz, 1998). These aspects, which tend to vary from territory to territory (Sabaté, Rodríguez and Díaz, 1995), led to consider the local context and its relationship with the global context, the family structures (kinship, class, age, ethnicity, religion, marital condition, matrimonial practices), the division of labor, of resources and of benefits, the use and distribution of time, as well as the access to power and decision making.

Results

The study zone

The Tulijá Valley has and extension of 1 289.20 Km², belongs to the Tulijá Tzeltal Chol Region of the state of Chiapas and extends almost entirely on the municipality of Salto de Agua. It limits to the north with the state of Tabasco and Palenque; to the south with the municipalities of Chilón and Tumbalá, and to the west with Tila. The territory of the Valley is fundamentally rural and has tall rainforest vegetation. The extensive forest and rainforest areas deforested have caused the loss of numerous species of flora and fauna (INAFED, 2010).

As the rest of the region, the Tulijá Valley territory was overexploited by settlers, mestizos and national and foreign businesses, under the exploitation of indigenous workforce and the extraction of precious woods, plantations of fruit trees, rubber, coffee and, recently, from the implementation of extensive livestock production, promoted strongly by the government during the decade of the 1940s, and in recent years also by the establishment of crops directed at the production of liquid biofuels, such as oil palm, driven by productive reconversion policies framed by a neoliberal model of economic development (Nazar et al., 2008).

Río Tulijá, Las Vegas and Tortuguero, 2ª Sección, are three ejidos that belong to the Tulijá Valley selected for this study (Figure 2). They refer to three indigenous localities that present a high degree of marginalization (CONAPO, 2010). The process of productive reconversion to oil palm has been carried out in most of their milpas or pasturelands during recent years. The conformation of the ejidos studied is placed during the decade of the 1990s within the framework of the extension and creation of new ejidos in Chiapas, product of the negotiations between government agrarian authorities and peasant organizations, resulting from the social movement unleashed from the uprising of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional in 1994 (Reyes, 2008).

Source: authors’elaboration with data from the State Committee of Statistical and Geographic Information (Comité Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica, CEIEG, 2017).

Figure 2 Spatial location of the study region.

The productive reconversion to oil palm in the three localities of study coincides with the previous visit by engineers and technicians who communicated to the local population how favorable the agroecological conditions of the territory are for palm cultivation, as well as its commercial and productive advantages. The plantations are installed under governmental programs based on single-time supports, which included the allotment of plants, fertilizers and, in some cases, economic resources for the expenses of establishing the crop.

The local context

The description of the local context in terms of the population points out that the localities of study are composed mostly by a young population (slightly over 75 % is under 36 years of age), with a higher masculinity index than the state rate, 107 men for every 100 women. Two main ethnic groups (Chol and Tzeltal) were identified, and the practice of ten different religions, with the following being the most important in numbers: Presbyterian, Pentecostal and Catholic churches, with percentages of 38.4 %, 18.3% and 15.6 %, respectively.

The three localities presented a high degree of marginalization and important gender differences in aspects such as access to education, bilingualism and spatial mobility. The women presented a position of disadvantage in access to education, in the condition of speaking Spanish, knowing how to read and write, and in the spatial mobility and range that the condition of migration entails. A relationship of significant statistical dependency (p<0.05) was found between gender and the condition of illiteracy and bilingualism.

The analysis of the local context in the family sphere pointed to asymmetries in the gender relationships based on local sociocultural and power practices. Most of the families are integrated from the married couple, with the most recurring being the nuclear type. The women heads of households are found primarily at the front of single-parent domestic groups. The comparison, insofar as the socioeconomic conditions, between men and women who are heads of households, reported that women are under conditions of disadvantages because they present higher proportions of illiteracy and monolingualism, and less availability of productive and political resources.

Patrilocality in matrimonial practices represented another unfavorable condition for women, since inside the domestic group decision making and exercise of power are related to gender, age and kinship. In turn, patrilineality in the local system of inheritance was reflected in the low percentage of property that women own, in comparison to men, contrasting with the greater amount of time that they invest in performing their responsibilities in the domestic group. The division of labor and of activities conditioned spatial mobility in addition to free time, showing differences between activities and, therefore, in the workspace, according to age and gender.

The main occupation presented statistically a relationship of dependency with the sex of the person (p<0.001) and the age range where they belong (p<0.001). The distribution of work and responsibilities by gender shows that unpaid domestic and reproductive work falls 98 % on women, while men are in charge of field work, recognized as the main economic activity of the region, in 97 % of the families.

The allotment per gender of activities influences decision making with regards to the destination of money. The women heads of households decide in 42 % of the cases about family expenditure, and in 15 % of the cases about the economic resources obtained from agriculture and livestock activities, where the trend to consult with their husband or family members increases. In their turn, the men heads of households decide about the agriculture and livestock income in a higher proportion (31.6 %) than about family expenditure (24 %), sharing this latter responsibility with their wives in 41.1 % of the cases.

Other gender differences were observed in the number of hours devoted to the main activities per week, presenting a relationship of statistically significant dependency (p<0.001). In this sense, women had a lower availability of free time; meanwhile, performing domestic activities implied in average 83 hours/week (s=21 hours), while agricultural and livestock activities had an average of 44 hours/week (s=14 hours).

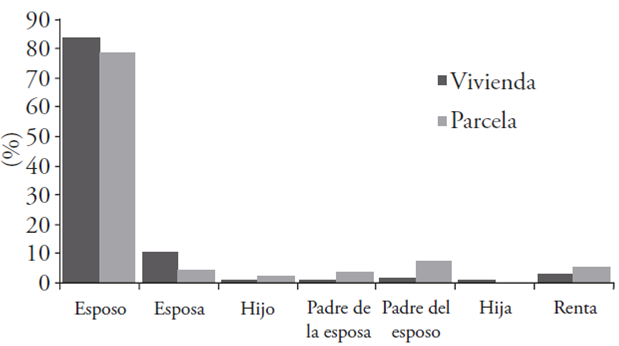

In general, the distribution of land ownership is mostly masculine, finding as owners the fathers (79%), their fathers (8 %) and their sons (2 %), while feminine ownership refers to women only in their role of mothers (4 %) (Figure 3). In agreement with this, the proportion of men and women ejidatarios is 94.3 % and 5.7 %, respectively, condition that is highly related to the participation and political representation of men and women inside the territory. For the New Agrarian Law from 1992, the men or woman ejidatario is the only agrarian figure that may enjoy all agrarian rights, such as the allotment of a plot, the right to lands of common use and to solares, as well as full participation in representative organizations of the ejido and the community (Reyes, 2006); from this that the low participation of women in the Ejido Assembly is equivalent to low participation and political representation in the community.

Local impact of productive reconversion to oil palm

The interrelation of the global with the local processes is manifested primarily in the economic activities, the distribution of work and the benefits. In the economic sphere, agricultural and livestock activities were the ones of highest importance. The farmland is used to sow milpa, for extensive livestock production and cultivation of oil palm in different proportions, presenting differences in the percentage of land that families devote to the latter, related to how old the crop is in each locality (Figure 4).

Source: authors’ elaboration with field work data, 2014.

Figure 4 Percentage distribution of the plots according to diversification of agriculture and livestock activities per location.

Palm cultivation substituted in highest proportion the cultivation of maize or milpa (67 %), whose destination was self-supply and sale. The milpa, from which farmers obtain squash, yucca, banana, cacao, chayote, chili peppers and bean, in addition to maize, was found to be a very important resource for the families interviewed; from this that a large proportion of the production units that plant palm devote part of the land to milpa. In Río Tulijá and Las Vegas, slightly over 40 % of the families that produce milpa in addition to cultivating palm allocate 75 % of their land to the palm, while in Tortuguero, 2ª Sección, more than 80 % allocate less than half of their land to palm (Figure 5). In agreement, the scarcity of maize was reported, especially in Río Tulijá and Las Vegas, and its resulting recurring purchase.

Source: authors’ elaboration with field work data, 2014.

Figure 5 Distribution of families interviewed according to the percentage of land they devote to the cultivation of oil palm.

Firewood is also obtained from the milpa, which is used as the fundamental fuel for food preparation in 98 % of the families; in this sense, it was found that 78 % of the families with a plot that purchase firewood, plant oil palm. From the oil palm, the fruit bunches are harvested, which by not having a use in domestic productive units, have as sole destination the sale to local extracting plants.

The price paid for each kilogram of fruit depends, generally, on the value given internationally to oil palm, and locally it varies according to the geographic location and accessibility of each locality. In average, the kilogram of oil palm fruit was paid at $1.20 pesos, with a variation of up to $0.40 pesos per kilogram of fruit between localities. There is a marked masculinization in the process of commercialization of the palm fruit; there were no cases of direct participation of women reported in the activities of purchase or sale.

Work in palm cultivation is carried out primarily with family labor. The distribution of activities and space is related to gender, kinship and age. Most of the women who work with palm do it as an additional workday to their main activities in the household. In contrast with adult males, who tend to work in the cultivation five or six days per week, women work no more than two days per week, their presence in the plot is related primarily with the harvest period which is every 15 days. The work that they carry out in the palm plantations has to do with cleaning the plot and collecting the fruit, activities in which children also participate.

Close to half of the families that cultivate palm inherited the plot with the crop already established; in the other cases, the decision to reconvert the production of the plots was taken mostly by the adult males of the families. This decision was shared with the women, fundamentally in their role of wives, only in 30 % of the cases. The adult women, mothers or wives, share the decisions regarding the earnings obtained from the palm in most of the cases with their husband or family members; they devote this money primarily to the household expenses and needs of the family.

Impact differentiated by gender

FAO (2008) points out that productive reconversion directed at the production of biofuels in peripheral countries can have negative repercussions for rural women by increasing their marginalization and threatening their means of subsistence. In the localities studied it was found that productive reconversion to oil palm weakens the local system of food provision, exacerbating the change from self-consumption to monetarization of the family income.

When intervening in the local production and availability of foods of daily use like maize, bean and other products of family consumption, the cultivation of palm in detriment of the milpa implied negative consequences for the families, primarily for women, who are responsible for the family diet. In a similar way, the availability of firewood, presented as the most frequently used fuel in the preparation of foods, and which is obtained fundamentally from milpas and pasturelands, decreases in accessibility, becoming increasingly more a merchandise of local consumption on which women depend in particular for the performance of their daily activities.

The resulting monetarization of relationships of exchange and consumption relegate families, especially women, to taking on a role of potential consumers. The production of palm fruit, whose only destination is sale to the exterior, breaks down the traditional relation of house and plot as productive unit, increases the gap between the productive and reproductive spheres, which is framed within an intense sexual division of labor, translates into the exacerbation of the exclusion of women in the economic-productive-political scope, increasing with this their vulnerability and dependency.

The monetarization of the family income marginalizes women from the most dynamic economic spaces by having a limited participation in the production and sale of the palm fruit, fostering a greater dependency of them on handout programs that have had to reinforce the subordination of women by promoting the traditional sexual division of labor and the governmental control of their responsibilities, in combination with a lower participation in decision making within the territory.

In agreement with the observations by Rossi and Lambrou (2008), who point out that the risks implied by the productive reconversion to biofuel production, there are gender differences; meanwhile, the socioeconomic conditions, the type of public policies, as well as the different functions and gender-differentiated responsibilities define the degree of vulnerability in these processes. It was found that the public policies that promote the productive reconversion in combination with structural gender inequalities tend to increase the vulnerability and exclusion of women. In this sense, gender inequality in land ownership translates into the systematic reduction of resources in women’s hands, historical condition that is intensified under the new productive and consumption relationships entailed by the cultivation of oil palm.

The cultivation of oil palm does not allow it to be implemented in lands that are loaned or rented, which is why having the ownership, control and use of the plot is a basic condition. The small proportion of women who own plots reflects, in addition to their low political and representation power in the community, their scarce participation as beneficiaries of government programs related to productive reconversion, such as the allotment of plants, inputs, economic support or credits for production which, it has been said, are essential for the subsistence of these crops, turning this into a situation of exclusion that increases their vulnerability in the local productive and economic sphere.

Obtaining economic income was identified as the main advantage of oil palm cultivation; however, it was found that the income obtained from these plantations does not have a significant effect on the socioeconomic conditions of the families. From the Chi-squared test (X²), the statistical relation between some indicators of marginalization and gender differentiating the families that cultivate palm from those that do not, point out that the asymmetrical gender relations and the conditions of social marginalization have not been modified significantly from the reconversion to oil palm.

Table 2 shows some results from the Chi-squared test of independence (x²), which related socioeconomic indicators of the domestic groups that cultivate palm from those that do not, revealed there is a relationship of dependency between the condition of cultivating palm or not doing it with the type of material that overlays the floor of the household (p<0.05). In that case, the analysis of the contingency table shows that most of the families whose house has dirt floors do not cultivate palm, while most of those that have floors covered with cement belong to families that plant palm, suggesting the improvement of these can be an advantage of cultivating oil palm.

Table 2 Chi-squared χ2 test of independence between families that plant palm or not, with socioeconomic indicators and of gender relations.

| Variable/indicador | Valor de χ2 | gl | Probabilidad (p) | Significancia |

| Nivel de hacinamiento | 1.872 | 2 | 0.392 | ns |

| Material de las paredes de la vivienda | 1.816 | 2 | 0.403 | ns |

| Material del piso de la vivienda | 7.413 | 2 | 0.025 | * |

| Material del techo de la casa | 1.598 | 2 | 0.450 | ns |

| Tiene refrigerador | 0.157 | 1 | 0.692 | ns |

| Tiene estufa | 0.189 | 1 | 0.664 | ns |

| Tiene vehículo | 1.561 | 1 | 0.212 | ns |

| Migración | 2.937 | 3 | 0.401 | ns |

| Tipo de familia | 4.211 | 4 | 0.378 | ns |

| Propietario (a) de la vivienda | 10.243 | 5 | 0.069 | ns |

| Propietaria (o) de la parcela | 6.932 | 4 | 0.140 | ns |

| Decisión sobre el gasto familiar | 7.240 | 6 | 0.299 | ns |

| Decisión sobre el ingreso agropecuario | 3.308 | 5 | 0.653 | ns |

N:189, Significance: *significant (p<0.05), ** Significant (p<0.01), ns: non-significant (p>0.05).

Source: authors' elaboration with field work data, 2014.

Conclusions

The promotion of productive reconversion to oil palm in small-scale peasant and indigenous units has different angles. Despite the negative, social and environmental impact that this crop entail, denounced even by international organizations like the United Nations and the World Bank, it is true that its promotion and financing from local, national and international agents, public and private, has been defining for its development.

Local and regional public policies foster the cultivation of oil palm from incentives and support programs for productive reconversion, in detriment of supports for the production of other crops of family and local consumption. International cooperation programs find favorable agroecological and political conditions, such as the low environmental regulation and the “availability” of lands, and recommend to local governments the implementation of the crops as a measure for rural development. International agreements promote investments for the research of this type of crops, and organizations like the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank grant financing for the promotion of these plantations.

Under the logic of international treaties and within the framework of a neoliberal development model, the cultivation of oil palm is promoted in peasant and indigenous lands of poor countries in favor of the demand from the international market. This panorama shows a series of political contradictions, finding that multilateral organizations like the World Bank, which despite recognizing the negative social and environmental impacts of oil palm cultivation is at the same time present as a vital source of financing for the establishment and maintenance of the plantations. In agreement, the PRODESIS, project of international cooperation with the European Union, whose objective is sustainable social development, promotes the monocrop of oil palm in the buffering zone of the Chiapas rainforest.

The impact that oil palm plantations generate in the territory studied is related to the consequences of monoculture, finding dependency on the external requirements, and subordination relationships to the international market and to government programs. This causes changes in the local social and economic relations, and impacts differentially on the daily life of men and women. The implications and risks of these practices depend to a great extent on the existing gender relationships, and from these, also the new relationships and strategies that are adopted in daily life.

At the regional level, the sociocultural, economic and political context of the territory studied is complex, due to the historical overexploitation of their natural and social resources, the convergence and interests of agents of different nature, as well as because of the conditions of marginalization of most of their inhabitants. The cultivation of oil palm involves the social restructuring of the territory; meanwhile, new and diverse men and women actors with different interests and positions of power integrate and act in these. According to local sociocultural and power practices, the analysis of the context in the family sphere pointed to asymmetrical gender relations that are reflected in the inequalities between men and women in terms of land ownership, division of labor, benefits and power, which in turn have disadvantageous implications, visible or not, especially for women whose families have redirected their partial or total production to palm cultivation.

The cultivation of oil palm and its impact in the decrease of the milpa weakens the local systems of food and fuel supply, with negative consequences for the families, especially for women who are responsible for the domestic group’s diet. As a result from productive reconversion, the monetarization of the family income keeps women at the margin of the most dynamic economic spaces, limiting their participation in the production and sale of the palm fruit. Gender inequality in land ownership for palm cultivation translates into the systematic reduction of the resources in the hands of women, and a lower participation and representation in decision making inside the territory.

Obtaining economic interests is manifested as the main advantage of oil palm cultivation; however, it was found that the income obtained from these plantations does not have a significant effect on the socioeconomic conditions of the domestic groups. This suggests that the policies that promote productive reconversion as a measure for rural development, from the monetarization of exchange and consumption relations, have not impacted favorably the families, exacerbating instead other problems related to the social contradictions inside the territory and the unmodified structural inequalities of gender.

The territory studied here is shown as the representation, material and symbolic, of the inequalities in the different variables contemplated, leading to the differentiated impact between its various women and men actors, related in their different scales and dimensions. It brings to light that global economic processes, which are materialized in this case in the neoliberal public policies such as the promotion of productive reconversion to oil palm, carried out in a territory whose socioeconomic and political context is gender differentiated, present the risk of increasing the inequality inside it and moving away from the discourse of inclusive rural development.

Literatura Citada

Arias, Joaquín, Jennifer Olórtegui, y Vania Salas. 2007. Lecciones aprendidas sobre políticas de reconversión y modernización de la agricultura en América Latina. Perú: Instituto Interamericano de Integración y Cooperación para la Agricultura. [ Links ]

Banco Mundial, Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura, y la Alimentación y Fondo Internacional para el Desarrollo Agrario. 2012. Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Manual sobre género en agricultura. Washington DC: Banco Mundial. [ Links ]

Castro, Gustavo. 2009. México: Los efectos de la palma africana. Gloobal. México DF: Gloobalhoy, No. 22. Disponible en http://www.gloobal.net/iepala/gloobal/fichas/ficha.php?entidad=Textos&id=11551&html=1 [ Links ]

Chauvet, Michelle, y Rosa González. 2013. La crisis alimentaria y los biocombustibles. In: Rubio, Blanca (coord). La crisis alimentaria mundial. Impacto sobre el campo mexicano. México DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población. Índices de marginación. 2010. Documento principal. México DF. Disponible en http://www.conapo.gob.mx [ Links ]

CEIEG (Centro Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica). 2017. Subsecretaría de Planeación Dirección de Geografía, Estadística e Información. http://www.ceieg.chiaps.gob.mx [ Links ]

De la Cruz, Carmen. 1998. Guía metodológica para integrar la perspectiva de género en proyectos y programas de desarrollo. España: Instituto Vasco de la Mujer, Instituto de Estudios sobre el Desarrollo y la Economía Internacional, Universidad del País Vasco. [ Links ]

FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2008. La producción de biocombustibles a gran escala puede aumentar la marginación de las mujeres. FAO, Roma. [ Links ]

Fletes, Héctor, Francisco Rangel, Apolinar Oliva y Guadalupe Ocampo. 2013. Pequeños productores, reestructuración y expansión de la palma africana en Chiapas. Región y Sociedad. Hermosillo, México: El Colegio de Sonora, Vol.XXV, N° 57. [ Links ]

Friedrich, Theodor. 2014. La seguridad alimentaria: retos actuales. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Agrícola. Tomo 48, Núm. 4. [ Links ]

Fritscher, Magda. 1990. Los dilemas de la reconversión agrícola en América Latina. Sociológica. México DF: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Vol. 5 N° 13. [ Links ]

German, Laura, George Schoneveld, y Pablo Pacheco. 2011. The social and environmental impacts of biofuel feedstock cultivation: evidence from multisite research in the forest frontier. Ecology and Society. Vol. 16, Núm. 3. Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04309-160324 [ Links ]

HLPE (Grupo de Alto Nivel de Expertos sobre Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición). 2013. Los biocombustibles y la seguridad alimentaria. Un informe del Grupo de alto nivel de expertos en seguridad alimentaria y nutrición del Comité de Seguridad Alimentaria Mundial. Roma. http://www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe/es/ [ Links ]

INAFED (Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal). 2010. Sistema Nacional para el Desarrollo Municipal. http://www.inafed.gob.mx/ [ Links ]

Morales, Magdalena, y Benito Salvatierra. 2012. Capital Territorial del Valle del Tulijá: caso de los choles de Salto de Agua, Chiapas, México. Temas Antropológicos. México Mérida: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Vol. 34, Núm. 1. [ Links ]

Nazar, Salvatierra, y Zapata. 2008. ¿Puede disminuirse la desnutrición infantil mediante políticas sociales y de reconversión productiva? El casos de la población ch’ol del norte de Chiapas, México. In: Martínez, Rosa, Rojo, Gustavo, Azpíroz, Hilda, Zapata, Emma y Ramírez, Benito (coords). Estudios y propuestas para el medio rural. México: Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México, Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Montecillo, Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Puebla, Tomo IV. [ Links ]

PRODESIS (Programa de Desarrollo Sostenible Integrado y Sustentable). 2005. Estudio de viabilidad de plantaciones de palma africana en la región de la Selva. Proyecto de Desarrollo Social Integrado y Sostenible Chiapas, México-Unión Europea. México. [ Links ]

Proyecto Mesoamérica. 2013. Disponible en: http://www.proyectomesoamerica.org/ [ Links ]

Reyes, María Eugenia. 2008. Los nuevos ejidos en Chiapas. Estudios Agrarios. México DF: Procuraduría Agraria, Núm. 37. [ Links ]

Reyes, María Eugenia. 2006. Mujeres y tierra en Chiapas. Revista El Cotidiano. México DF: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Vol. 21, Núm. 139. [ Links ]

Rossi, Andrea, y Yianna Lambrou. 2008. Gender and equity issues in liquid biofuels production. Minimizing the risks to maximized the opportunities. Italy Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [ Links ]

Sabaté, Ana, Juana Rodríguez, y Ángeles Díaz. 1995. Mujeres, Espacio y Sociedad. Hacia una Geografía del Género. España Madrid: Editorial Síntesis S.A., Colección Espacios y Sociedades. [ Links ]

Santacruz, Eugenio, Silvia Morales, y Víctor Palacio. 2012. Políticas gubernamentales y reconversión productiva: el caso de la palma de aceite en México . Observatorio de Economía Latinoamericana. Revista académica de economía. Núm. 170. [ Links ]

SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera). 2017. Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. Secretaría de Agricultura Ganadería Desarrollo Rural Pesca y Alimentación. http://www.siap.gob.mx/ [ Links ]

Tepichín, Ana, Karine Tinat, y Luzelena Gutiérrez (coords). 2010. Introducción. Los Grandes problemas de México. México DF: Colegio de México, Vol. VIII. [ Links ]

Received: June 2014; Accepted: November 2017

texto em

texto em