Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versão impressa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.15 no.3 Texcoco Jul./Set. 2018

Articles

The Agrarian Reform and Changes in Ejido Land use in Aguascalientes, 1983-2013

1Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C., Av. Instituto Politécnico Nacional 195, Playa Palo de Santa Rita Sur, La Paz, B.C.S. 23096, México.

2Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes. Departamento de Disciplinas Agrícolas, Av. Universidad 940 Cd. Universitaria, Aguascalientes, Ags. 20131, México.

In 1992 the Agrarian Reform established measures to regulate the land market in agrarian nuclei, giving certainty to land tenure. Presumably, these measures changed the livelihoods of the population and the territorial structure. The objective of this study was to assess the possible effects of privatization of ejidos on the changes in land use in the state of Aguascalientes. The state represents a classical model of agrarian-urban-industrial transition. Land use maps were elaborated for the period of 1983 to 2013. The exchange rates in land use were calculated and compared between decades and in function of their degree of privatization. It was found that the process of certification and acquisition of full dominion of the lands took place in an accelerated manner during the first years of the reform’s implementation. The dynamic of land use change increased in the first years of certification; these changes are independent of the degree of privatization. The factors associated to these processes were discussed in function of the regional context and urban planning. Emphasis is made on the importance of elaborating policies with an integral approach that allows a balanced territorial development.

Key words: rural development; territorial planning; PROCEDE; land tenure; urbanization

En 1992 la Reforma Agraria estableció medidas para regularizar el mercado del suelo en los núcleos agrarios, dando certidumbre a la tenencia de la tierra. Presumiblemente estas medidas modificaron los medios de vida de la población y la estructura del territorio. El objetivo de este estudio fue valorar los posibles efectos de la privatización de los ejidos sobre los cambios del uso del suelo en el estado de Aguascalientes. El estado representa un modelo clásico de transición agraria-urbano-industrial. Se elaboraron mapas de uso del suelo para el periodo de 1983 a 2013. Se calcularon las tasas de cambio en el uso del suelo y se compararon entre décadas y en función de su grado de privatización. Se encontró que el proceso de certificación y adquisición del dominio pleno de las tierras ocurrió de manera acelerada en los primeros años de actuación de la reforma. La dinámica de cambio de uso del suelo se incrementó en los primeros años de certificación; estos cambios son independientes del grado de privatización. Se discutieron los factores asociados a estos procesos en función del contexto regional y la planeación urbana. Se hace énfasis en la importancia de elaborar políticas con enfoque integral que permitan un desarrollo territorial equilibrado.

Palabras clave: desarrollo rural; ordenamiento territorial; PROCEDE; tenencia de la tierra; urbanización

Introduction

This study had the objective of assessing the impact of the certification and the privatization of ejidos on land use changes within the context of urbanization and industrialization of Aguascalientes. The working hypothesis was that the reforms eased the acquisition of reserves for urban and industrial development and that the change in economic activities of the population has favored the recuperation of the plant cover in the region.

At the end of the 1970s, Latin American countries established deep structural and monetary changes liberating their economies, with the aim of participating in a more competitive way in international markets. These reforms were motivated by the World Bank recommendations that strove to give legal certainty to the communal lands and thus to reach a greater economic welfare through access to credits for production and the generation of terms for the sale and rent of properties at a fair price (World Bank, 1975; Deininger and Binswanger, 1999; Liverman and Vilas, 2006). In the case of Mexico, these recommendations agreed with the rural-urban transition of the population. The cities grew exponentially with invasions of communal lands, giving place to “irregular settlements”. These settlements were inhabited by vulnerable groups that were occasionally regulated and endowed with services, while the land owners received insufficient pay for their properties (Bojórquez-Luque, 2011), so recommendations by the World Bank were integrated into the policies of Mexican territorial planning.

Prior to this and as result of the Mexican Revolution, a prolonged process of land distribution was implemented from 1917 to 1992. At the end of the period, more than half of the territory was assigned to peasants under the form of what we know today as ejidos and agrarian communities (Zúñiga and Castillo, 2010; RAN, 2014). Ejidos are agrarian nuclei with autonomy in land management that mix private and common goods. They are divided into four zones: (1) human settlement; (2) growth reserve; (3) farming lands; and (4) communal lands (Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria, 1992). In their origin they had strict rules that prohibited the sale and rent of the land. In turn, sowing the farming lands was considered to be mandatory, since idle lands were expropriated from their owners (CEPAL, 2002; Warman, 2003). In 1992 a reform was implemented that gave total autonomy to the ejido assembly in decision making in matters of land use and enabled the ejidatarios to make a partial or total division of their lands to be transferred to the regime of private property through the acquisition of full dominion (Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria, 1992; 1993; Barba and Valencia, 2013). To regulate these sales and with the aim of giving legal certainty to land tenure, in 1993 the Certification Program of Ejido Rights and Entitlement of Urban Plots (Programa de Certificación de Derechos Ejidales y Titulación de Solares Urbanos, PROCEDE) was created, which by its end in 2006 had given out tenure titles to 92-24 % of the agrarian nuclei. During the certification the external and internal limits of the ejidos were measured, and the four zones that integrated them were defined, all of this in agreement between the ejido assembly and the agrarian authorities (Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria, 2006).

With the certification, the objective was to strengthen the permanence of the ejido by recognizing its autonomy, facilitating access to credits, fostering community organization, generating a heritage, making a more efficient use of natural resources, and providing legal mechanisms for the acquisition of reserves for urban development (RAN, 2006). The PROCEDE promoters were optimistic regarding the idea that certainty in land tenure would increase productivity of the land, through access to credits and a better administration of the territorial resources, avoiding the well-known tragedy of the commons. In their turn, local governments would attain the possibility of having territorial resources for the expansion of urban centers and service provision (Dunn, 2000; Barnes, 2009). However, another sector criticized the initiative, highlighting that the peasants would lose their organizational ability and would become less competitive; in particular, taking into account the signing of international free trade agreements and the adoption of neoliberal policies. Therefore, the certification would promote an exodus of the socioeconomically vulnerable population towards recently consolidated industrial areas and characterized by a greater economic dynamism (Murphy, 1994).

According to Zúñiga and Castillo (2010), the reforms generated social changes without benefitting economically the peasantry and detonated the privatization of land, taking the ejido to the collapse. Numerous studies described deep changes in the social structure of the peasantry after the implementation of PROCEDE in different regions of the country, which are related to the local culture and the attachment to traditional livelihoods, but they do not evaluate their possible effects on changes in the use of land and natural resources (Stanford, 1994; Yetman and Búrquez, 1998; Yetman, 2000).

In the Center-West Region, a large part of the valleys and other flatlands were transformed intensively for agricultural and livestock production before 1920. The use of the region was underlined as clearly agricultural due to the large number of flat soils with good drainage. Likewise, the region houses a deep livestock production tradition that dates back to Colonial times (Lizama, 1994; SAGARPA, 2011). However, at the beginning of the 1980s the cities of the region began to be developed as industrial zones, and states like Aguascalientes left aside the small-scale primary production, leaving the primary sector in hands of businessmen with enough resources to modernize the production and to enter international markets (Salmerón, 1998; FIDERCO, 2004; González, 2011). The urbanization of the region was part of a decentralizing policy of economic activities that had the aim of generating economic development poles, ensuring regional development and consolidating the development of the main cities in the country: Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey (Díaz-Quintero, 1994). With the growth of the cities in this region and the terms provided by the 1992 reform, it would be expected for peri-urban ejidos to become integrated into the urban growth, and that, given the new conditions of employment, the abandonment of small-scale agriculture and livestock production would take place. Agricultural abandonment would generate a similar process to the one that took place in Europe and the United States, with the so-called theory of forest transition (Mather, 2001; Wrigth and Muller-Landau, 2006; Rudel et al., 2010).

The theory of forest transition establishes that changes in the plant cover of a region have a “U” shape; that is, there are processes of deforestation when drastic changes in the economy of the region take place and then there is a moment of recovery of the vegetation during industrialization stages (Rudel et al., 2010). Different studies suggest that forest transition in Mexico is more complex than in Europe and the United States because the population has cultural rooting for the territory and agriculture, which entails that the moments of vegetation recovery happen by short time periods (Aide et al., 2013). The bulk of these studies belong to regions with a high percentage of indigenous presence, such as the Yucatán Peninsula, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Huasteca Potosina and Veracruz, where certainly agriculture is a fundamental part of the local culture (García-Barrios et al., 2009; Tenza-Peral et al., 2011; Vaca et al., 2012). However, other regions without indigenous presence and with limitations for production, linked to climate change (droughts) and the ill management of natural resources, such as overgrazing and erosion, have not been evaluated. It is suggested that this type of spaces are more prone to the abandonment of agriculture and livestock activities when more viable economic actions appear, and this would represent an opportunity for conservation of natural resources which, according to the theory of forest transition, would allow entering a process of recuperation.

This document describes the changes in land use in the ejidos of the state of Aguascalientes in the period of 1983 to 2013. The hypothesis is that the privatization of ejidos accelerated the patterns of change in land cover of the peri-urban zones of the state, which would result in the increase of urbanization at the expense of a decrease of the forest and agricultural surface, while the ejidos that are not peri-urban undergo a process of forest recovery and agriculture abandonment.

Materials and Methods

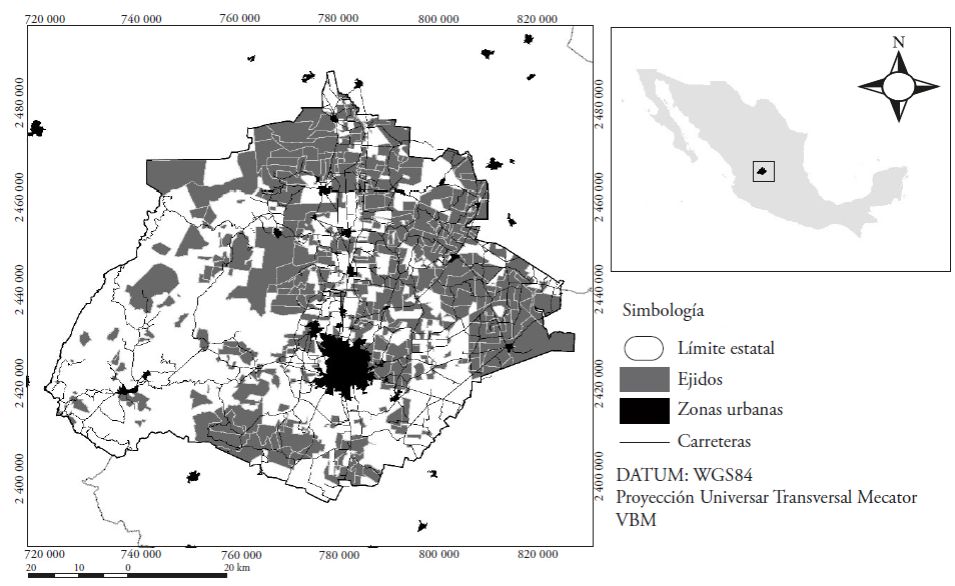

Changes in land use in the state of Aguascalientes were analyzed by decades from 1983 to 2013. Aguascalientes is located in the Center-West Region of Mexico, between coordinates 22° 27’ N, 102°52’ W and 21° 28’ N, 101° 53’ W (INEGI, 2013; Figure 1). The state is made up of 184 ejidos that cover 49.2 % of the total state surface (265 082 ha); inside them, they house 48.5 % (126 464.08 ha) of the total forest resources (260 520.66 ha; INEGI, 2011) and 10.6 % of the total population (125 802 inhabitants; INEGI, 2010). Until 1960, 52.3 % of the economically active population was devoted to agriculture and livestock production (Dirección General de Estadística, 1960), although in 1970 the population devoted to it decreased to 36 % (Dirección General de Estadística, 1970). In the last census, it corresponds only to 6.34 % of the economically active population (INEGI, 2010). This change of economic activity corresponds to the local policies of technological and industrial promotion, implemented in 1968 and which were strengthened in 1979 with the federal policy of economic decentralization that classifies Aguascalientes as a priority region for industrial development (Secretaría de Patrimonio y Fomento Industrial, 1979). The policy of economic decentralization allowed the negotiation of subsidies for the installation of industries and increased foreign investment in the state (Secretaría de Economía, 2011). In economic figures, the metal mechanical industry displaced agricultural and livestock production that in 1970 generated 19.3 % of the Gross Domestic Product and which currently contributes 4.5 %, leaving in a condition of vulnerability the rural population (INEGI, 1989; INEGI, 2009; SEDESOL, 2011; SEGUOT, 2014).

Source: INEGI, 2010; RAN, 2014.

Figure 1 Geographic location of the state of Aguascalientes and the ejidos.

Land tenure in the ejidos

To have the information from the changes in land tenure, the files of the ejidos in Aguascalientes in the Historical Register of Agrarian Nuclei (Padrón Histórico de Núcleos Agrarios, RAN, 2015) were reviewed, and the surfaces and years were obtained in which the ejidos from Aguascalientes were certified and obtained the full dominion of their lands.

Analysis of the change in land cover

The changes in land use in the ejidos between decades and according to their degree of privatization were compared. To have an idea of the effect of urbanization on the changes in land use of the ejidos, the rates of urban growth among ejidos located in peri-urban and not peri-urban zones were compared.

To define the changes in land use, LANDSAT MSS, TM5, ETM7 and OLI8 satellite images were obtained, corresponding to the years 1983, 1993, 2003 and 2013. The images were obtained from the site of the Geological System of the United States of America (USGS, 2015). These correspond to the drought period (April-May), which is why there is no cloudiness. After an atmospheric and geometric correction, they were classified in a supervised way, using the ERDAS Imagine 2014 software (Integraph, 2013). With these, thematic maps were elaborated at a scale of 1:75,000, with a certainty of classification of 95 %. Nine categories were chosen: (1) forest, (2) closed shrub, (3) open shrub, (4) grassland, (5) irrigation agriculture, (6) rainfed agriculture, (7) bodies of water, (8) human settlements, and (9) soil without apparent cover. As a whole, the first four categories were defined as areas covered by vegetation. The surfaces of change in land use were obtained and with them the net rates of change in land cover were calculated from 1983 to 1993, 1993 to 2003 and 2003 to 2013, using the formula by FAO (1996):

where: TC: Rate of change of use i; Si 1 : Surface of the use i in the initial time; Si 2 : Surface of the use i in the final time; n: number of years between initial time and final time.

Effect of the certification on the change in land use

To relate the effect of the privatization of ejidos with the rates of change in land use, a variance analysis was performed, establishing as determinant factor the percentage of lands with full dominion in the ejidos (none, <25 %, 25-50 % and >50 %).

Results and Discussion

Certification of ejidos and acquisition of full dominion

The historical pattern of agrarian nuclei shows that the totality of the ejidos in Aguascalientes has titles and certificates of tenure: 172 were certified by PROCEDE and the 12 remaining were certified after 2006 with the Support Fund for Agrarian Nuclei without Regularization (Fondo de Apoyo para Núcleos Agrarios sin Regularizar, FANAR). The acquisition of Full Dominion has taken place in 65.1 % of the ejidos. Most certificates were issued in 1994 and 100 % was reached in 2012 (Figures 2 and 3). This agrees with what was reported by Zepeda (1998), who described that the small states were the ones that presented a greater advance in the certification during the first four years of life of PROCEDE. The fast certification happened due to logistical ease to measure ejidos and thanks to the ease in signing the agreements in the ejido assembly. The certification was voluntary, which is why the social conditions were determinant. Our study zone is socially calm (there are no data of uprising or strikes), which is why agrarian conflicts like those that happened and led to armed uprising in Chiapas did not take place (Dietz, 1995; Nuño, 1996; Bartra and Otero, 1998).

Source: Padrón Histórico de Núcleos Agrarios, 2016.

Figure 2 Accumulative percentage of ejidos by year when they were certified or obtained full dominion of their lands.

Source: elaborated by the authors with information from the Padrón Histórico de Núcleos Agrarios (RAN, 2015).

Figure 3 A. Location of the ejidos by year of certification; B. Location of the ejidos by year of acquisition of full dominion.

In addition to the logistical and social ease cited in the prior paragraph, the fast certification process and acquisition of full dominion agrees with the whole of economic processes that surround the Center-West Region in the decade of the 1980s. The need for land for urban and industrial development made circulate among the peasantry the idea that the lands close to urban centers would increase their value, with which the peri-urban ejidos would be the first to privatize their lands (Verduzco-Miramón and Seefóo, 2014). This phenomenon has been described in detail for the peri-urban eijdos of Mexico City (Larralde-Corona, 2012).

In the case of Aguascalientes, given its geographical position, the low incidence of natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods and its social calmness, important automobile industries and their subsidiaries had already been established in 1980 (Gutiérrez, 2016). This generated for the population to double in two decades, going from 519 439 inhabitants in 1980 to 1 184 996 inhabitants in 2010 (INEGI, 2012). The demographic growth happened primarily through immigration from neighboring states and the highest growth arose in the city of Aguascalientes and along the Pan-American Highway (Salmerón, 1998; López- Flores, 2013). The urban sprawl of the capital city grew 8163 ha in the period from 1980 to 2010 (1587 ha in 1980, 9750 ha in 2000; SEDESOL, 2011). With the change in economic model, traditional orchards, whose production supplied exclusively the local market, disappeared in the capital. In addition, due to the new neoliberal policies and of commercial openness, small-scale producers lost competitiveness in the markets and terms, such as the guarantee prices (Valdivia et al., 1991). In this sense, the lands became the most important part of the economic patrimony of the families, so that privatization of the land happened first in ejidos close to the urban zones and did not happen in more inaccessible places (Figure 3).

The growth of human settlements

Before the Agrarian Reform (1983-1993), urban zones grew at a rate of 7.36 % (357 ha per year) over private properties, while irregular settlements (on ejido lands) grew 353.27 ha in 10 years (Table 1, Figure 4). In the next decades, a marked increase in the growth of human settlements can be seen in the peri-urban and not peri-urban ejidos, which reached their maximum growth rate from 1993 to 2003. In this period the urban zones increased their surface in 54.87 %: two thirds on private properties and a third on ejido land (Figure 4). We think that the increase in urbanization on ejido lands reveals the success of the reforms in diversification of land offers for urban growth.

Table 1 Surface of human settlements per decade in Aguascalientes.

| Superficie (ha) | Tasa de crecimiento anual (%) | ||||||

| 1983 | 1993 | 2003 | 2013 | 1983-1993 | 1993-2003 | 2003-2013 | |

| Ejidos periurbanos | 967.1 | 1320.3 | 2870.5 | 3827.9 | 3.16 | 8.08 | 2.92 |

| Propiedad privada periurbana | 3452.7 | 7023.4 | 10 051.4 | 13 322.4 | 7.36 | 3.65 | 2.86 |

| Ejidos no periurbanos | 1733.1 | 2295.3 | 4450.2 | 4938.2 | 2.85 | 6.85 | 1.05 |

| Propiedad privada no periurbana | 65.4 | 81.3 | 92.3 | 121.7 | 2.20 | 1.28 | 2.81 |

Source: data obtained by the authors from thematic maps.

Source: authors’ elaboration based on the classification of satellite images.

Figure 4 Net growth of human settlements in Aguascalientes from 1983 to 2013.

The urbanization process in Aguascalientes has been characterized by being relatively ordered and planned based on Urban Development Programs. These programs include zoning maps and have a rigid application, whose planning horizons are estimated to be in 25 years. In fact, up until the end of the 1990s the territorial reserves were anticipated to urban growth, which is why there has never been a land deficit and the acquisition of ejido land has taken place in a gradual and ordered manner (Jiménez-Huerta, 2000; López-Flores, 2013). However, in the last decade the government ceased to acquire lands for growth reserves, leaving the market in the hands of real estate developers. According to Jiménez-Huerta (2013), the process of ejido land acquisition was eased by expropriations. The ejidatarios received a payment for the lands with values above the costs fixed by the Commission of Appraisal of National Properties (Comisión de Avalúos de Bienes Nacionales); with this, the early acquisition of growth reserves was achieved without social conflicts (Figure 4).

We highlight that the growth of human settlements in not peri-urban ejidos was higher than in the peri-urban (Figure 4). It is possible that these figures have been overestimated in the thematic maps, because due to the geographic scale used the edifications and other rural elements were generalized, such as: idle plots, street plans, family orchards, among others. This causes for the perimeter classified as human settlement to have a larger extension than the actual one. Therefore, the typical disperse arrangement of rural human settlements multiplied by the high number of disperse rural localities resulted in a larger surface of human settlements. However, we cannot rule out that there was growth favored by the endowment of reserves of ejido growth.

Change in ejido land use

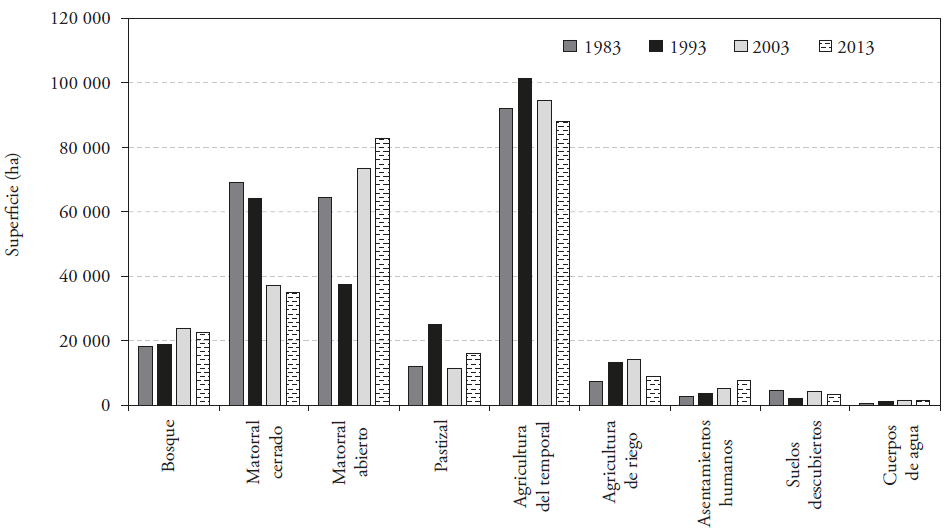

Between 1983 and 2013, there was a growing trend in the surface of human settlements, forests and open shrubs (Figure 5). The rainfed agricultural surface increased 9054 ha, while irrigation surface increased 5792 ha in the period of 1983 to 1993. In the next two decades, the abandonment of agricultural lands happened, both irrigation and rainfed (Figure 5). From 1983 to 2013, 4316 ha of farming lands were lost, equivalent to 4.67 % of the initial surface; this value could be lower taking into account that farming lands have resting periods; this can be seen in Figure 6, which shows that 29% of the surface of grasslands were transformed into agriculture and 28 % of agricultural lands that were abandoned transformed into open shrubs. Even so, the abandonment of small-scale agriculture is an action to be expected in urbanized territories that in turn present water deficits and where drought affects production (FAO, 2009; Liverman and Vilas, 2006). In Aguascalientes, harvest losses from the effects of drought are documented, which, for example, in 2010 reached 42 229 ha, equivalent to 31 % of the surface sown that year (SAGARPA, 2011). Despite its high loss rate, there is not a generalized phenomenon of agricultural abandonment or of rural depopulation in Aguascalientes. According to information obtained through interviews (without publishing), it is understood that the population in the ejidos alternates employment in industry and services with the traditional activities of agriculture and livestock production. This particular situation of the peasantry makes the existence of a forest transition process inviable.

Source: authors’ elaboration based on the classification of satellite images.

Figure 5 Land cover of ejidos for the years 1983, 1993, 2003 and 2013.

Source: authors’ elaboration based on the classification of satellite images.

Figure 6 Replacement between different types of land cover in the ejidos of Aguascalientes between 1993 and 2013. The numbers indicate the percentage of the original cover that was transformed; for example, 60.6 % of the rainfed agricultural surface was transformed into irrigation agriculture and 3.24 % of the irrigation surface was converted into rainfed agriculture.

Regarding forest resources (forests, shrubs and grasslands), their recovery after 1993 is an optimistic scenario for the conservation of natural resources in the region. Chapa-Benzanilla et al. (2008) describe the gradual recovery of the forest cover inside the Sierra Fría Natural Protected Area.

The authors conclude that the recovery rates are reaching those of forest degradation. In our case, the forest zones that show recovery correspond to ejidos whose polygons of common areas are located in zones separated by several kilometers from the plotted areas and of human settlement, or else, they correspond to surfaces within the Sierra Fría Natural Protected Area. This allows assuming that the inaccessibility of these ecosystems has made their exploitation impossible (Figure 7). This condition of environmental equilibrium makes the zone susceptible to receiving funds in matters of environmental services and a good place for ecological restoration.

Source: authors’ elaboration from the classification of satellite images.

Figure 7 Net annual change rates. The negative values indicate a decrease in the use, and positive values an increase.

In the case of shrubs and grasslands used as pasture lands there is a decline in the plant density (Figure 6). The closed shrubs and grasslands have been substituted by other degraded open ones, or in incipient stages of development. This degradation reduces relevantly the productivity of pasture lands (De Alba, 2008). The loss of cover of shrubs reached its highest levels in intermediate years of the certification between 1993-2003 (Figures 6 and 7). The deterioration of the vegetation is a piece of data that has already been reported by other authors like Siqueiros-Delgado et al. (2016), who point out that 60 % of the vegetation in the state shows signs of deterioration. We ignore the direct factors associated to the loss of plant cover, which is why we recommend monitoring its dynamic. Siqueiros-Delgado et al. (2016) and De Alba (2008) mention that the bad conditions of the vegetation results exclusively from overgrazing; however, there are no precise data about the number of livestock heads and their variation in time, which is why we cannot leave aside other possible factors linked to climate change, such as pests and droughts.

This study complements what was reported by Braña and Martínez (2005), who did not find significant evidences that PROCEDE is associated with the probability of deforestation in the ejidos. In our study zone PROCEDE catalyzed the degradation process of the vegetation, since the greatest changes in land use or events of forest degradation took place immediately after the certification (Figures 6 and 7). This degradation did not reach total deforestation and in the cases where regeneration of the vegetation happened in abandoned agricultural plots, it has masked the processes. We suggest performing studies of the dynamics of land use in other regions with a study horizon of more than 10 years to compare the dynamics.

Full dominion and the trend in change of land use

Until April 2016, 31,934 ha (12 % of the total ejido surface) had been converted in the full dominion regime (private properties). The discrete figure of privatization agrees with what was described by Barnes (2009), who suggests that the privatization policies of ejido lands did not present the farmland-city exodus projected. The autonomy of the ejidos made evident the low capacity for organization and governance among the peasantry, who on the one hand carry out the formal mechanisms for the regime change of their lands and, in contrast, opt for selling their lands in an informal way (Murphy, 1994; Salazar, 2014). The informal trade of land causes the data provided by the National Agrarian Registry to be insufficient to specify the possible relation between privatization and changes in land use, which is why our results should be taken with certain caution.

We did not find evidence of the acquisition of full dominion being related significantly (p>0.05) with the rates of change in land use (Figure 8). There is, however, an increasing trend in the growth rate of human settlements as the privatized surface increases (Figure 8). This trend is related to the strict urbanization policies in place in the state (Gobierno del Estado, 2013) and to the fact that they operate with more rigor in areas close to the capital.

Figure 8 Net annual change rates in land use according to the degree of acquisition of full dominion. F values between groups: Agriculture, black squares, F=1.996, p=0.116; Vegetation, dark grey circles, F=0.053, p=0.984; Human settlement, light grey rhombus, F=0.882, p=0.452.

In contrast, the agricultural and vegetation areas have a tendency to decrease their surface when privatization increases (Figure 8). The acquisition of full dominion is linked directly to the possibilities of selling lands. In recent years an increase in the so-called special developments has been seen, which include country and tourism developments which by nature are located in zones with scenic beauty and high natural value. The sale of this type of “country plots” takes place without regulations in terms of urban development. An example are the developments located in the only gallery forest with ahuehuete cypreses (Taxodium mucronatum), known as “El Sabinal”. The way of operating consists in eliminating elements of the vegetation at a small scale that are not appreciated (grasses, natives, nopal, acacia, among others); then, exotic species are sown and the plots are sold which are built over in the short term, in a disperse manner (H. Ayuntamiento del Municipio de Aguascalientes, 2014).

Conclusions

The changes in land use are described in this document, after the application of reforms in matters of land tenure. Based on the objectives of the 1992 Agrarian Law (giving legal certainty to land tenure, fostering the efficient use, conservation and administration of natural resources in the country, and encouraging commerce and investment), we conclude that certainly titles and certificates of tenure were given to 100 % of the communities and ejidos in Aguascalientes, which has given legal certainty to the original owners of the land. The informal sale of lands has not been stopped, so the privatization data of the National Agrarian Registry do not allow evaluating the effects of privatization on the changes in land use in ejidos. The certification and acquisition of full dominion favored urban growth since lands were acquired for cities’ growth.

The greatest changes in land use happened from 1993 to 2003, immediately after the ejido certification. Based on the changes of land cover, there is no evidence that the reform fostered an efficient management of the natural resources, insofar as the current vegetation has a lower quality than the one present in 1983. This reflects the lack of mechanisms for adequate control and management in rural zones. It is not possible to link this exclusively to the ejido certification and to the privatization of lands due to the decrease in agricultural surfaces and the bad quality of the natural resources, since the factors that promote these changes were not assessed. These factors could be of various natures: economic, social, cultural, climatic, topological, etc. It will be necessary in other studies to inquire about these causes.

There is no evidence that the theory of forest transition operates in this region, so that the forest recovery cannot be linked exclusively with industrialization and urbanization. Rather, it is the result from the fact that more vegetation has been recovered in the state than what has been deforested, and that inaccessible sites ceased to be exploited. This equilibrium is fragile and variable between years, so it should not be overlooked that the vegetation recovered does not have the quality of the original vegetation.

Agricultural abandonment takes place as in pulses, and the areas that are not incorporated into urban development are prone to be reused. Aguascalientes shows an extraordinary phenomenon, since the rural population mixes agricultural and livestock tasks with urban employment in the industry and services, so that the predictions of rural abandonment did not come true. The will of peasants to diversify their economic options without losing their agrarian identity is an interesting theme for future studies in this and other regions.

The informal market of lands continues and should be prevented with rigorous policies of control of land use, where planning does not exclude the rural zones from its development plans. The trends observed make evident the success in the application of urban-regional policies set in motion since 1970 and consolidated with the 1989 decentralization policy for economic activities (Garza, 1986; Presidencia de la República, 1989). Aguascalientes certainly has a gross domestic product per capita higher than some neighboring states, but it has achieved it without connecting urban development with rural development, so that there is a centralized growth of the capital city accompanied by a high dispersion of rural localities that coexist with natural resources that are increasingly degraded. If the trend of these processes continues, it will be impossible for rural inhabitants to maintain their traditional economic activities and in the end they will limit notably their livelihood capitals.

The current configuration of land uses is the result of a complex of interactions between local and regional policies of urban development, economic development, and the characteristics of the peasant population, and they are not an exclusive product of agrarian reforms.

Forest areas that are in frank recovery can be evaluated to become an objective of environmental policies, such as payment for environmental services and reforestation programs that allow channeling the increasingly scarcer public resources to places where the policies show successful results. It is necessary to foster integral projects of rural development that allow ordering the territory and which improve the living conditions of the population.

Finally, it is important to mention that the methodology developed in this study can be extrapolated to the analysis of other states of the Republic and other Latin American countries.

Literatura Citada

Aide Mitchell, T., Matthew Clark, Ricardo Grau, David López-Carr, Marc Levy, Daniel Redo, Martha Bonilla-Moheno, George Riner, María J. Andrade-Núñez, y María Muñíz. 2013. Deforestation and Reforestation of Latin America and the Caribbean (2001-2010). Biotropica 45(2):262-271. [ Links ]

Barba Solano, Carlos, y Enrique Valencia Lomelí. 2013. La transición del régimen de bienestar mexicano: entre el dualismo y las reformas liberales. Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 22(2): 47-76. [ Links ]

Barnes, Grenville. 2009. The evolution and resilience of community-based land ternure in rural México. Land Use Policy 26:303-400. [ Links ]

Bartra, Armando, y Gerardo Otero. 1998. Movimientos indígenas campesinos en México: La lucha por la tierra, la autonomía y la democracia. In: Sam Moyo y Paris Yeos (coords). El resurgimiento de movimientos rurales en África, Asia y América Latina. CLACSO (Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales) 4001-428 p. [ Links ]

Bojórquez-Luque, Jesús. 2011. Importancia de la tierra de propiedad social en la expansión de las ciudades en México. Ra Ximhai 7(2): 297-311. [ Links ]

Braña, V. Josefina, y C. A. L. Martínez. 2005. El PROCEDE y su impacto en la toma de decisiones sobre los recursos de uso común. Gaceta ecológica 74:35-49. [ Links ]

CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). 2002. La sostenibilidad del desarrollo en América Latina y el Caribe: desafíos y oportunidades. CEPAL-PNUMA. Santiago de Chile, 241 p. [ Links ]

Chapa Bezanilla, Daniel, Joaquín Sosa-Ramírez, y Abraham De Alba Ávila. 2008. Estudio multitemporal de fragmentación de los bosques en la Sierra Fría, Aguascalientes, México. Madera y Bosques 14: 37-51. [ Links ]

De Alba Ávila, Abraham. 2008. Ganadería. In: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) (coord). La Biodiversidad en Aguascalientes: Estudio de Estado. CONABIO, Instituto del Medio Ambiente del Estado de Aguascalientes (IMAE), Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes. México pp: 268-271. [ Links ]

Deininger, Klaus, y Hans Binswanger. 1999. The evolution of the World bank´s land policy: Principles, Experience and future challenges. The World Bank Research Observer, 14(2):247-276. [ Links ]

Díaz-Quintero, Miguel Ángel. 1994. Una Aproximación territorial de las ciudades medias de México en los ochenta. Clío 10: 23-36. [ Links ]

Dietz, Gunther. 1995. Zapatismo y movimientos étnico-regionales en México. Nueva Sociedad 140: 33-50. [ Links ]

Dirección General de Estadística. 1960. VIII Censo General de Población 1960. Disponible en: http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/ccpv/1960/ [ Links ]

Dirección General de Estadística. 1970. IX Censo General de Población 1970. Disponible en: http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/ccpv/1970/default.html [ Links ]

Dunn Malcolm. 2000. Privatization, Land Reform, and Property Rights: The Mexican Experience. Constitutional Political Economy, 11:215-230. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 1996. Forest resources assessment 1990. Survey of tropical forest cover land study change process. Roma, Italy. 152 p. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2009. La FAO en México. Más de 60 años de cooperación 1945-2009. FAO, México, D.F. 370 p. [ Links ]

FIDERCO (Fideicomiso para el Desarrollo de la Región Centro Occidente). 2004. Programa de desarrollo de la Región Centro Occidente. Guadalajara. 90p. [ Links ]

García-Barrios, Luis, Yankuic M. Galván-Miyoshi, Abril, Valdivieso-Pérez, Omar R. Masera, Gerardo Bocco, y J. Vandermeer. 2009. Neotropical Forest Conservation, Agricultural Intensification, and Rural Out-migration: The Mexican Experience. Bioscience 59:863-873. [ Links ]

Garza, Gustavo. 1986. Institucionalización de las políticas urbano-regionales del estado mexicano. Gaceta Mexicana de Administración Pública Estatal y Municipal. 15-27. [ Links ]

Gobierno del Estado. 2013. Código de Ordenamiento Territorial, Desarrollo Urbano y Vivienda para el Estado de Aguascalientes. Periódico Oficial del Estado de Aguascalientes. Decreto número 394 07 de octubre de 2013. [ Links ]

González Rodríguez, Manuel. 2011. Políticas de competitividad como estrategia para el crecimiento económico urbano-regional: El sector manufacturero en ciudades de la región centro-occidente 1990-2003. Revista Fuente 3(9):115-136. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Castorena, Pablo. 2016. Política pública de control obrero y desarrollo industrial en Aguascalientes, México. Revista Brasileira de Planejamiento e Desenvolvimiento. 5(3):475-503. [ Links ]

H. Ayuntamiento del Municipio de Aguascalientes. 2014. Programa Subregional de Desarrollo Urbano de los Ejidos Salto de los Salado, Agostaderito (Cuauhtémoc-Las Palomas), San Pedro Cieneguilla y Tanque de los Jiménez. Periódico Oficial del Estado de Aguascalientes. Tomo LXXVII Número: 6. 10 de febrero de 2014, pp: 2-97. [ Links ]

Herrera, Francisco. 1996. Apuntes sobre las instituciones y los programas de desarrollo rural en México. De estado benefactor al estado neoliberal. Estudios Sociales. 17(33): 7-39. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 1989. Censos económicos. Disponible en http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/ce/ce1989/default.aspx [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 1990. XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2009. Censos económicos. Disponible en: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/ce/default.aspx [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2010. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Disponible en: www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/ccpv/2010/Default.aspx. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2011. Uso del suelo y Vegetación; Datos vectoriales escala 1:250,000 serie V. Disponible en: www.inegi.org.mx/geo/contenidos/recnat/usosuelo/Default.aspx. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2012. Volumen y Crecimiento. Población total por entidad federativa, 1895-2010. Disponible en: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/sisept/Default.aspx?t=mdemo148&s=est&c=29192 [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2013. Marco geo estadístico 2013 versión 6.0 (Inventario Nacional de viviendas 2012). [ Links ]

Integraph. 2013. ERDAS Imagine, 2014. Hexagon geospatial. Norcross, EUA. [ Links ]

Jiménez Huerta, Edith. 2000. El principio de la irregularidad: mercado del suelo para vivienda en Aguascalientes, 1975-1998. Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara. 245p. [ Links ]

Jiménez Huerta, Edith. 2013. Oferta de suelo servido y vivienda para la población de escasos recursos en Aguascalientes. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 29 p. Disponible en: https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/jimenez-wp14ej1sp-full_0.pdf [ Links ]

Jones, Gared A., and Peter M. Ward. 1998. Privatizing the Commons: Reforming the ejido and urban development in Mexico. International Journal of Urban and Regional Reseach. 22: 76-93. [ Links ]

Klooster, D. 2003. Forest transitions in Mexico: Institutions and forest in a globalized countryside. Professional Geographer 55:663-672. [ Links ]

Larralde-Corona, Adriana Helia. 2012. La transformación del trabajo, la movilidad geográfica y las relaciones campo-ciudad en una zona rural del Estado de México. Economía Sociedad y Territorio, XII (40):619-655. [ Links ]

Liverman, Diana M., y Silina Vilas. 2006. Neoliberalism and the environment in Latin America. Annual Review of Environmental Resources, 31:327-363. [ Links ]

Lizama Silva, Gladis. 1994. Región e historia en el Centro-Occidente de México. Relaciones 60:13-39. [ Links ]

López-Flores, Netzahualcoyotl. 2013. Bases Socio-espaciales en el crecimiento de la Ciudad de Aguascalientes: procesos de apropiación y segmentación del espacio urbano. Tesis para alcanzar el grado de doctor en estudios urbanos. Universidad de Valladolid. Disponible en: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/4263 [ Links ]

Mather, Alexander. 2001. The transition from deforestation in Europe. In: Angelsen, Arild y Kaimowitz, David (eds). Agricultural technologies and tropical deforestation. CAB International. Wallingford, UK 35-52. [ Links ]

Murphy, Arthur. 1994. To title or not to title: Article 27 and Mexico’s Urban Ejidos. Urban Anthropology and Studies of cultural systems and World Economic Development. 23(2): 209-232. [ Links ]

Nuño Herrera, Eugenio. 1996. Aguascalientes: sociedad, economía, política y cultura. UNAM. México. 147 p. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República. 1989. Decreto por el que se aprueba el Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 1989-1994. Diario Oficial de la Federación. [ Links ]

RAN (Registro Agrario Nacional). 2006. Informe de rendición de cuentas 2000-2006. Libro Blanco PROCEDE. Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria, Procuraduría Agraria, INEGI, Registro Agrario Nacional. 132 p. Disponible en: http://www.ran.gob.mx/ran/transparencia/transparencia/DGFYA/Archivos/LB_PROCEDE.pdf [ Links ]

RAN (Registro Agrario Nacional). 2014. Sistema general de consulta del Archivo General Agrario. Disponible en: http://sicoaga.ran.gob.mx/sicoagac/ [ Links ]

RAN (Registro Agrario Nacional). 2015. Padrón Histórico de Núcleos Agrarios. Disponible en: http://phina.ran.gob.mx/phina2/ [ Links ]

Rudel Thomas, K., Laura Schneider L., and M. Uriarte. 2010. Forest transitions: An Introduction. Land Use Policy 27:95-97. [ Links ]

SAGARPA (Secretaría de Agricultura Ganadería y Pesca). 2011. Región Centro Occidente. Vocación y desarrollo. SAGARPA, México. 40 p. Disponible en: http://www.sagarpa.gob.mx/colaboracion/normatividad/Documentos/Monograf%EDas/Regi%F3n%20Centro%20Occidente.pdf [ Links ]

SAGARPA (Secretaría de Agricultura Ganadería y Pesca). 2011b. Servicio de información Agroalimentaria y pesquera. Disponible en: http://www.gob.mx/siap/ [ Links ]

Salmerón, C. F. 1998. Intermediarios del progreso: Política y crecimiento económico en Aguascalientes. Gobierno del Estado de Aguascalientes. Aguascalientes, México. 313 p. [ Links ]

Salazar, Clara. 2014. El puño invisible de la privatización. Territorios 30:69-90. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Economía. 2011. Inversión extranjera directa. Información histórica de flujos hacia México desde 1999. Disponible en: http://catalogo.datos.gob.mx/dataset/inversion-extranjera-directa [ Links ]

Secretaría de Patrimonio y Fomento Industrial. 1979. Plan Nacional de desarrollo Industrial 1979-1982. México 186 p. [ Links ]

Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria. 1992. Ley Agraria. Diario Oficial de la Federación Tomo CDLXI No. 18. 26 de febrero de 1992. [ Links ]

Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria. 1993. Reglamento de la Ley Agraria en Materia de Certificación de derechos ejidales y titulación de solares. Diario Oficial de la Federación Tomo CDLXXII No.3. 6 de enero de 1993. [ Links ]

Secretaría de la Reforma Agraria. 2006. Acuerdo por el que se declara cierre operativo y conclusión del Programa de Certificación de Derechos Ejidales y Titulación de Solares (PROCEDE) Diario Oficial de la Federación. Tomo DCXXXVIII No.13. viernes 17 de noviembre de 2006. [ Links ]

SEDESOL (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social). 2011. La expansión de las ciudades 1980-2010. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. México, Distrito Federal. 195p. [ Links ]

SEGUOT (Secretaría de Gestión Urbanística y Ordenamiento Territorial). 2014. Programa Estatal de Ordenamiento Ecológico y Territorial Aguascalientes 2013-2035. Periódico Oficial del Estado de Aguascalientes. Tomo LXXVII. No. 38. [ Links ]

Siqueiros-Delgado, María Elena; José Alberto Rodríguez-Avalos, Julio Martínez-Ramírez, y José Carlos Sierra-Muñoz. 2016. Situación actual de la vegetación del estado de Aguascalientes, México. Botanical Sciences 94(3):455-470. [ Links ]

Stanford, Lois. 1994. The privatization of Mexico´s ejidal sector: Examining local impacts, strategies and ideologies. Urban Anthropology and Studies of cultural Systems and World Economic Development 23 (2):97-119. [ Links ]

Tenza-Peral, Alicia, Luis García-Barrios, y Andrés Giménez-Casalduero. 2011. Agricultura y conservación en Latinoamérica en el siglo XXI: ¿Festejamos la transición forestal o construimos activamente la matriz de la naturaleza? Interciencia: Revista de ciencia y tecnología de América 36(7):500-507. [ Links ]

USGS (United States Geological Survey). 2015. USGS Global Visualization Viewer. Disponible en: http://glovis.usgs.gov [ Links ]

Vaca, Raúl Abel, Duncan John Golicher, Luis Cayuela, Jenny Hewson, y Marc Steininger. 2012. Evidence of incipient forest transition in Southern Mexico. PLoS One 7(8): e42309. [ Links ]

Valdivia Flores, Arturo Gerardo, Teódulo Quezada Tristán, y Armando Martínez de Anda. 1991. La productividad pecuaria en Aguascalientes. Revista Investigación y Ciencia de la UAA 3: 31-34. [ Links ]

Verduzco-Miramón, Francisco Javier y Seefoó Luján. 2014. Mercado de tierras en un ejido mexicano: El caso de Campos en Manzanillo, Colima, 1994-2013. Territorios 30: 91-108. [ Links ]

Warman, Arturo. 2003. La reforma agraria mexicana: una visión de largo plazo. In: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Reforma agraria. Colonización y Cooperativas.84-95. Disponible en: http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/j0415t/j0415t09.htm [ Links ]

Wrigth, Joseph, and Helene C. Muller-Landau. 2006. The Uncertain future of tropical forest species. Biotropica 38(4): 443-445. [ Links ]

World Bank. 1975. Land Reform. Sector Policy Paper. E.U.A., Washington D.C. 72 p. Disponible en: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/1975/05/439934/land-reform [ Links ]

Yetman, David, y A. Búrquez. 1998. Twenty-seven: a case study in ejido privatization in Mexico. Journal of Anthropological Research 54:73-95. [ Links ]

Yetman, David . 2000. Ejidos, land sales and free trade in Northwest Mexico: Will globalization affect the commons? American Studies 41(2/3):211-234. [ Links ]

Zepeda G. 1998. Cuatro años de PROCEDE: avances y desafíos en la definición de derechos agrarios en México. Revista estudios agrarios 9. Procuraduría Agraria. México D.F. 24 p. [ Links ]

Zúñiga Alegría, José G. y J. A. Castillo López. 2010. La Revolución de 1910 y el mito del ejido mexicano. Alegatos 75: 497-522. [ Links ]

Received: November 01, 2016; Accepted: March 01, 2017

texto em

texto em