Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.15 no.2 Texcoco abr./jun. 2018

Articles

From Indigenous Peasants to Tourism Promoters: The Experience of Ejido San Cristóbal, Hidalgo, México

1Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. México. (mfelix@uaeh.edu.mx)

The Tolantongo canyon is located in San Cristóbal, municipality of Cardonal, Hidalgo, México; it is considered unique in its genre in the state due to its botanical species, caves, and hot spring river. With these resources, the ejidatarios (shareholders of common land) created the “Tolantongo Caves Cooperative” (Cooperativa Grutas Tolantongo) to manage and formalize their tourism project. Currently, San Cristóbal is one of the main tourism destinations in Hidalgo; the project has detonated economic benefits for the ejidatarios and the rest of the population, and has generated multiplying effects at the regional level. The objective of this article is to analyze the factors that explain the conformation and organizational structure of the Tolantongo caves. For this purpose, ethnographic research was performed between May 2011 and May 2012, and July and August 2013; the techniques used were observation, literature review, and interview. The empirical evidence indicates a process of appropriation of natural resources, awareness of their wealth, defense of the territory, alternative development model, and community-based tourism, where the ancestral community structure has a preeminent role; all this within a context of latent tensions between the community principles, the capitalist economy, and with external agents such as the government and private interests.

Key words: assembly; alternative development; communal tasks; community organization; cargo system; community-based tourism

En San Cristóbal, municipio de Cardonal, Hidalgo México se localiza la barranca de Tolantongo, considerada como única en su género en la entidad por sus especies botánicas, sus grutas y su río de aguas termales. Con estos recursos los ejidatarios crearon la “Cooperativa Grutas Tolantongo” para administrar y formalizar su proyecto turístico. Actualmente, San Cristóbal es uno de los principales destinos turísticos en Hidalgo; el proyecto ha detonado beneficios económicos para los ejidatarios y el resto de la población, y ha generado efectos multiplicadores a nivel regional. El objetivo de este artículo es analizar los factores que explican la conformación y la estructura organizativa de las grutas Tolantongo. Para ello se realizó investigación etnográfica entre mayo de 2011 a mayo de 2012, y julio y agosto de 2013; las técnicas utilizadas fueron la observación, la revisión documental y la entrevista. La evidencia empírica indica un proceso de apropiación de los recursos naturales, conciencia de su riqueza, defensa del territorio, un modelo de desarrollo alternativo y turismo comunitario donde la estructura comunitaria ancestral tiene un papel preeminente, todo ello en un contexto de tensiones latentes entre los principios comunitarios, la economía capitalista y con agentes externos como el gobierno e intereses particulares.

Palabras clave: asamblea; desarrollo alternativo; faena; organización comunitaria; sistema de cargos; turismo comunitario

Introduction

San Cristóbal, municipality of Cardonal in the state of Hidalgo, México, illustrates the effects of transformations in the agricultural sector, on the one hand, and on the other the strategies for local development that the government promoted concurrently in the territories inhabited by peasants and indigenous peoples during the 1990s. Since this period, there is talk of an agricultural crisis product of the Neoliberal policies implemented by the State (dismantling of the protectionist model that characterized the Mexican countryside for decades, conclusion of the agrarian distribution, establishment of legal bases to open the land market through various commercial figures). These changes generated unemployment and exclusion in most of the peasants and only the producers with capitalist production conditions were looked after (Monterroso and Zizumbo, 2009; Rubio, 2006). Likewise, agrarian issues and peasant agriculture are no longer central to the decisions and strategies of the rural social subjects, but rather they have been replaced by the complex combination of multiple productive activities, sources of family income, and variety of migratory modalities (Vergara, 2011).

In terms of the options for local development executed by the State for the peasant population, there is, among others, the promotion of entertainment services, specifically alternative tourism. Although this modality arose in the rural areas of México in the 1970s, from the conception of the touristic ejido (shared land), it was not until the 1990s when federal programs were created to drive the economy in rural communities with a productive conception different from the daily tasks of peasants (Garduño, Guzmán and Zizumbo 2009). These actions are not circumstantial, if it is considered that 70 % of the property in the country is in ejidos and indigenous communities, and that in these territories there is a wide inventory of natural and cultural resources that constitute an important appeal. Therefore, facing the need to palliate the situation of the agrarian sector, generate employment and additional market to countryside products, alternative tourism was sought after (López and Palomino, 2008; Palomino et al., 2016). In this way, the promotion of this type of tourism from the State was carried out in a situation of structural crisis of the agricultural countryside, and as part of a central policy to ensure the conservation of biodiversity and to foster the social welfare of indigenous populations (Guzmán et al., 2013). It should be mentioned that, according to Guzmán et al. (2013), in México the environmental policy and biodiversity conservation programs have mechanisms (payment for environmental services, production and certification of organic foods, forest enterprises, ecotourism) and regulations (market instruments, auto-regulation schemes, and voluntary compliance) according to Neoliberal Conservation (NC). This term suggests that “nature can only be preserved if its conservation yields concrete economic benefits to the owners of the land and resources”. Likewise, “the transference of benefits from nature towards social groups is achieved by generating new merchandises” (Durand, 2014:91). Therefore, for these authors, NC entails the commercialization of nature (transformation of elements and phenomena of free access, atmospheric oxygen, landscapes, genes, and water) and of culture (turned into spectacle, with stereotypical images of rural inhabitants).

Despite this context of NC, the studies of tourism enterprises carried out in the rural and indigenous territories in México show complexities and contradictions, such as the absence of a fast and total transformation of peasant communities; not only are reactions of resistance and protest generated, but rather local cultures question, negotiate and adapt to the Neoliberal and public policies (Guzmán et al., 2013; Durand, 2014; Palomino et al., 2016). This generates processes of creative adjustment, generating “hybrid patterns in property regimes, in the forms of organization, and in economic exchanges” (Wilshusen, cited in Durand, 2014: 195). In this regard, López and Palomino (2008) also underline that not everything can be reduced to business criteria and government intervention schemes, but rather that there is a relation with the community social sphere.

Reviewing the case of San Cristóbal has precisely the aim of emphasizing the role of the community organization in the process of appropriation of natural resources, defense of the territory, conformation of the tourism project, development model, and entrepreneurial management. San Cristóbal will also resent the measures of Neoliberal cut, provoking labor migration from its most productive population towards the United States of America. However, adjacent to this, the inhabitants will undertake their tourism project, called Tolantongo Caves, which is managed by a cooperative society by the same name. The project has been accompanied by the State in some stages, but there have also been moments of confrontation between both parts. As a result, a contention process was generated, defense of the territory, and rejection of one of the biodiversity conservation mechanisms (establishment of a Natural Protected Area). In addition, this strengthened the autonomy in the administration of the tourism project, and the negotiation capacity of ejidatarios with external agents. Currently, the Tolantongo Caves is one of the main tourism destinations in Hidalgo and is part of the tourism corridor: health spas and hot springs, one of the seven corridors established in the state (the others are Huasteca, Haciendas, Tolteca, Sierra-Huasteca, Four Elements and Mountain). According to information by the Ministry of Tourism and Culture in Hidalgo, between Easter Week and the summer of 2015, from the total tourists recorded, 78 % went to the health spas and hot springs corridor. Also, from the economic spill generated in these two periods of highest tourism attendance, 71 % came from this same corridor. This accounts for the transcendence of the hot springs projects established in Hidalgo, such as the one in Ejido San Cristóbal. In fact, this locality has also been seat in recent years for state government meetings with federal officials in the delivery of resources for tourism in the state. In addition, San Cristóbal today has an infrastructure (facilitated by the economic earnings from the tourism project) that is not seen in other localities or in the municipal seat to which it belongs, which is why it is hard to categorize it within the standards of the traditional definition of a rural locality. On the other hand, the model of development and tourism business goes beyond the entrepreneurial principles and the capitalist rationality where the community organization still has a central role.

The structure of this document begins with a review of alternative development, indigenous community and community-based tourism; then, the locality of San Cristóbal is described, and later the organizational characteristics and effects of the tourism project are analyzed. In terms of the methodology, field work was carried out between May 2011 and May 2012, in July and August 2013, and in January 2017 there was a visit to San Cristóbal to update some sections. The techniques used were observation, literature review, and interview; observation was carried out in some assemblies, communal tasks, festivities (patron saint’s celebrations) and in the Tolantongo canyon. The literature review was performed in the National Agrarian Registry and the Historical Archive of the State of Hidalgo. In the first, basic files from Ejido San Cristóbal were examined, and in the second some official federal journals were reviewed. The literature review also included the internal regulations of the community, some requests and minutes provided by the communal authorities. The snowball technique was applied for the interviews1; the respondents were community civil authorities, elderly people, representatives of the committee and the cooperative society, migrants, and women.

Alternative development, community and community-based tourism

Alternative development or another kind of development emerged since the 1970s and it is a normative approach that prioritizes the content of the development rather than the mode (Hettne, 1990). For Veltmeyer (2000; 2003), since the 1980s there is a search for Alternative Development (AD) and what defines its conceptions is that: development is heterogeneous, it can take multiple modes; the peoples manage to build their own development on the basis of autonomous actions by organizations based on the community, local or basic; the development ought to be participative in mode, human in scale, and centered on the people. Regardless of the diversity of postulates of the different AD models, Veltmeyer identifies four nuclei related to them, such as: 1) community as a basis; 2) participation as essential solidarity budget; 3) local action and control; and 4) integrity of the process. Regarding the first point, it recognizes that it is rural communities that constitute the object of rural development or development based on the community (2003:44) because in these contexts the community musters certain conditions (sense of social identity, belonging and mutual obligation). According to Veltmeyer (2000), participation as essential solidarity budget entails for the object of the process to be at the same time collectively subject and for it to be constituted as protagonist of the community development in every and all of its dimensions (economic, social, political, cultural, ethnic and ecologic). Meanwhile, the local action and control insist in the convenience of distancing (momentary and selective) from the perspective of the global scope or, at least, on having a more reduced vision, aware of everything that affects directly the local scope. Finally, the integrity of the development process entails the nexus between the social and the economic, and of both with regards to the environment, the relative equity to the distribution of the amount of resources, and the continuous human scale of the organization’s characters and of the development.

In face of the context of AD, its current search, as suggested by Veltmeyer, and the community as one of its main characteristics, there emerged aspects in a collateral way that accentuate the role of indigenous peoples in these processes. Among these there is ethno-development and good living. The first was pioneer in the discussion related to indigenous peoples with development and the right that these peoples had to define it; he highlighted the impacts of public policies of which they had been object, and ethnocide. Ethno-development also accentuated the use of the modes that belong to social organization, which, according to Bonfil (1995), referred to collective work and traditional government institutions, referring to the structure of the indigenous community. In turn, good living (which arose at the end of the nineties in Latin America in countries like Ecuador and Bolivia) suggests going beyond alternative development, since it attempts to break with the commonly accepted ideas of development as growth or progress (Gudynas, 2011). In addition, it questions, among others: a) the aspiration of development as a linear process of historical sequences that must be repeated; b) the recognition of nature as subject of rights and various ways of relational continuity with the environment; c) social relations that are not economized or reduced to commercial goods or services; and d) reconceptualization of the quality of life in modes that do not depend only on the possession of material goods or income levels (Gudynas, 2011: 18-19). Some scholars converge in that the meaning of good living includes: good cohabitation, access and enjoyment of material and immaterial goods; harmonious relationships between people which is directed at the satisfaction of human and natural needs; effective and spiritual realization of people in family or collective association in their broader social environment; reciprocity in exchange relationships and local management of production, and cosmocentric vision (Farah and Vasapollo, 2011: 22). One of the basic elements of good living is also the community where the human being is only part of this unit, since other elements are included (nature, ancestors). Likewise, community indigenous institutions are highlighted, spaces where relationships of reciprocity and good cohabitation are expressed such as thaki (path), related to community service (Albo, 2008).

Supporters of alternative development and promoters of ethno-development and good living agree on the role that the community has and some of its components. This term, for the case of the Otomí indigenous community of Valle del Mezquital (indigenous group to which San Cristóbal belongs), is made up of the territory, kinship relationships, communal government, and relationships of cooperation and exchange. The last two are expressed in these three articulated axes: 1) community assembly; 2) cargo system; and 3) communal tasks. In general, the community assembly is the maximum authority, where issues of collective interest are treated. Therefore, it is a public forum of democratic deliberation performed face to face, participative and seeking consensus. Thus, the decisions that emanate from the assembly are legitimized and will be respected by all, including those that do not attend (Schmidt 2012). The cargo system is composed by a complex framework of representations in the civil and religious spheres. The civil authority is known as delegate (the government of the state of Hidalgo contemplates it in the Municipal Organic Law and in Otomí language is known as nzäya), where together with other members (holder, substitute, and helpers) represent the community authority. The election is made in assembly through the habits and customs and the posts are honorary; the same happens with religious authorities (although those who perform these activities are people who profess the Catholic religion). In this cargo system, there is also a combination of what Korsbaek (1996) has pointed out: hierarchy (to occupy the post of highest authority a corporate structure is used), social prestige, rotation, honorific exercise, and service as synonym of authority. In turn, community tasks have a similar sense, as happens with other indigenous peoples in México (tequio, fajina, mano vuelta, service to the people, among other denominations). In sum, this collective work has the main function of providing a service to the community in the infrastructure and services tasks. For Warmam (2003), collective work represents one of the most vigorous institutions for social cohesion and for persistence of the community. The assembly, cargo system, and community tasks are part of the communality of Otomí people, understood as the “complex system of cultural values, principles, relationships and social attitudes that give structure to a communal institutionality, with which a constant balance is pursued between obligations and rights (posts, tequios, services) of those who belong to a common territory and assume the collective responsibility (assembly), and on a destiny that is also common” (Aguilar and Velázquez, 2008:417). These three articulated axes make possible a governance system. It is also characterized by citizen involvement in decision making, which denotes a horizontal structure, co-responsibility between actors, transparency and accountability (Palomino et al., 2016:24).

In addition to accounting for the reproduction of Otomí peoples in Valle del Mezquital, the assembly, cargo system and communal tasks are also significant to complement some collective actions such as defense of the territory, entrepreneurship and project maintenance; among these, community-based tourism. This type of tourism has been linked within alternative tourism, which emerged at the end of the 20th century, product among other things of an environmental preoccupation and crisis of the conventional model of mass tourism (sun and beach). This generated more participative and specialized touristic activities (ecotourism, rural tourism, adventure tourism) which expressed the revaluation of nature, rural culture and a different use of free time. In addition, these modalities attempted to reconcile development with regards to local cultures and the preservation of the environment (Palomino et al., 2016; Guzmán et al., 2013). According to Maldonado (2005:5), community-based tourism refers to a way of “entrepreneurial organization sustained on the ownership and self-management of community patrimonial resources, with arrangement to democratic and solidary practices in work and in the distribution of benefits generated by the provision of tourism services, looking to foster intercultural encounters of quality with visitors”. In turn, Fernández (2011:55) points out that community-based tourism can result in a Community-Based Business (CBB), understood as a collective social enterprise founded on a group’s culture, based on shared values (solidarity, mutual support, sense of belonging and social identity), social capital (to obtain internal and external resources), whose objective is the creation of social values (benefits of social and cultural type beyond mere financial benefits).

According to Palomino et al. (2016), in México community-based tourism enterprises began in the 1990s derived from factors such as: a government policy that considered tourism activity as a development factor, which is why it was diversified with other modalities; fluidity of resources to address poverty and for conservation in vulnerable populations; presence of natural resources and cultural goods in indigenous territories; and the fact that some indigenous organizations and communities identified in tourism an opportunity to recover the use and usufruct of their territories. According to these authors, some organizational principles that influence the functioning of community-based tourism are: a) social land-ownership regime (to determine logics of collective use and usufruct of the territory and its resources); b) location in areas of high environmental value with possibility of generating conservation practices; c) system of governance and community institutions (as a framework of social arrangements that regulate the collective praxis); and d) organization of enterprises (makes it possible to display organizational and productive management capacities). As will be shown later, the type of tourism practiced in Ejido de San Cristóbal gathers several principles of community-based tourism.

The locality of San Cristóbal

San Cristóbal is a community of Otomí origin with ejido (shared land) property, located in the municipality of El Cardonal (Figure 1). This municipality as some others that make up the region of Valle del Mezquital (one of the nine geographic regions in the state of Hidalgo, which presents two contrasting zones: arid and irrigation) is distinguished for being located in the arid zone and, according to census data from 2010, 64.3 % of its population are indigenous language speakers, and it has a very high degree of migratory intensity (CONAPO, 2012).

San Cristóbal is also made up of the following blocks: El Centro, Tolantongo, Molanguito, Agua Nueva, El Pájaro, El Manchado, El Toxthi, El Vixtha and La Loma. Tolantongo is the place where the canyon is located and, therefore, the tourism project is established there. Most of the community infrastructure is found in the center (health clinic, schools, hostel, church, cemetery, auditorium, among others). In San Cristóbal, what defines the sense of belonging of these blocks to the community is the relationships of cooperation and work. According to census data, San Cristóbal has 673 people: 48 % are men and 52 % are women, and 15.5 % of this population is older than three years old and speaks an indigenous language.

Inhabitants of San Cristóbal received their first agrarian endowment in 1934, where the Tolantongo canyon was included: a geographic mass with a series of natural landscapes, such as hot spring caves, an underground tunnel, a waterfall, a river, various water holes, and botanical species. This panorama contrasts with other points of San Cristóbal, where an arid and dry climate predominates, and basic crops (primarily maize) depend on seasonal rainfall. Those that integrated the ejido considered in their agrarian request the canyon, since the hillsides of the Tolantongo River were the privileged place where water could be accessed and land could be farmed. In 1936, they requested an enlargement of the ejido that was not granted until 1953; in 1962 they negotiated a second enlargement of the ejido. According to information from the National Agrarian Registry, Ejido San Cristóbal has a total surface of 4365.3 hectares. Of these, 431.1 are plotted lands, 29.5 are human settlements, 3889.4 are of common use, and 15.1 are reserve. According to data from Monterroso and Zizumbo (2006), each ejidatario has four rainfed hectares in average and half a hectare under irrigation. In 1993, the Certification of Ejido Rights and Garden Titling Program (Programa de Certificación de Derechos Ejidales y Titulación de Solares, PROCEDE), was carried out in the ejido, so the ejidatarios obtained their plot titles and the possibility to sell their lands. However, in an assembly celebrated that same year it was agreed not to sell plots to people outside the ejido. This response from the ejidatarios reflects one of the counter-productive effects of the agrarian reform from 1992. As Wilhusen points out (cited in Durand, 2014:195), the impacts of the country’s legislation were not as broad and the ejidatarios have shown certain ambivalence in the privatization of their lands.

According to the information from the authorities, until January 2017 there were 140 ejidatarios; 96 have their plot certificates and a certificate of common use. These 96 people are the ones who have formal agrarian rights, the rest are also called ejidatarios through other informal mechanisms. Of this universe of 140 people, there are only four women, who entered by succession, which implies that males have been privileged in this process. The community membership in San Cristóbal revolves, then, around the figures of ejidatarios and avecindados. The ejidatarios are the most distinguished group and there are two forms of becoming an ejidatario: by succession (following the precepts of Agrarian Law, so there are formal agrarian rights), and by what they call el mérito (by merit), that is, as a result of work and service to the community (without agrarian rights). The ejidatario (or successor) who is a title-holder has obligations (performing communal tasks, exercising posts as authority for the ejido or the community) and rights (access to land and to services such as water, electricity, schools, health, burial in the cemetery, and has all the benefits offered by the cooperative society). Therefore, the obligations of the ejidatario who enters by merit are similar to those of the ejidatario by succession, although they differ in some rights (cannot be an authority of the ejido, only has access to one garden, will receive utilities from the cooperative society gradually over a period of seven years, age limit to enter as partner is 25 years). In terms of the avecindados, all of them have a kinship relationship with the ejidatarios (formal and by merit) and also have obligations and rights, although they cannot be members of the cooperative. The entry of ejidatarios as partners and of avecindados to the community, as well as the retirement of both from service and work (when they turn 65 years of age), are heard and legitimized by the assembly. San Cristóbal is also ruled by internal regulations. Although they were promoted by the agrarian authorities, they were adapted to the needs of the community; thus, the type of property and the habits and customs are part of the content, the regulations cover everything that refers to the cooperative society and community issues. Their weight is such that if someone transgresses their principles he is punished, with expulsion from the community being the highest sanction.

It should be mentioned that in San Cristóbal, a migratory tradition arose towards the capital city (Distrito Federal) since 1940, which decreased at the end of the 1980s to be directed towards the USA. This migration dates back to 1949 (although there are no residents who participated in the Bracero Program); it was interrupted in 1953 and resurged in 1986. Some of these migrants from the 1980s were benefitted with the legalization program offered by the USA. Between 1990 and mid-2000, this migration reached its maximum and was characterized by its undocumented character, was mostly masculine. These men were primarily single and were of the most productive ages.

Tourism project: Tolantongo Caves Ejido Cooperative Society

The caves that emanate from the Tolantongo canyon are cataloged as unique of their type in Hidalgo and in Valle del Mezquital, which is why San Cristóbal is one of the most important touristic destinations in Hidalgo, both domestic and foreign. According to authorities, the cooperative society had 150 base employees in 2016, 350 during weekends and close to 700 in high seasons such as Easter Week. This holiday period tends to be the most important in the year due to the attendance of tourism; according to the authorities the average number of tourists during Easter Week was between 50 and 60 thousand people.

The foundation of the tourism project as such dates from 1975; this act coincides, on the one hand, with the implementation of other tourism projects that were implemented in the country and were recognized in this same decade in article 144 of the Agrarian Reform (Casas, cited in Garduño et al., 2009: 13). On the other hand, the dirt road that leads to the caves was finished that year; previously, the only way of reaching this natural attraction was by walking or renting a beast of burden. In this project the ejidatarios had the support of the Indigenous Patrimony of Valle del Mezquital (state agency created by presidential decree in 1952 in charge of the development policies for the indigenous population), especially of its representative Maurilio Muñoz Basilio, character pointed out by Mendoza (2007) as a figure who questioned the cacique structure of this state organization. The dirt road was significant for the growth of tourism and the detonator for ejidatarios to begin organizing around this activity. In this context, the ejidatarios were warned by Muñoz Basilio of the possible foreign interests for their natural resources for tourism exploitation, to what they responded “dead here, but not defeated” (Mr. Odilón, interview August 25, 2011).

Regarding these external interests, there are those of private individuals and the state and federal governments. About the first, two facts stand out: one about a person who traded (on May 6, 1947), 179 hectares of ejido lands, where the Tolantongo canyon was included, with the aim of building a health spa, a hotel and a hydroelectric plant taking advantage of the river waters. This was done in exchange for another 179 hectares of hillside pasturelands from his property. In the official document it was indicated that there was an economic compensation to pay for the irrigation lands present in the canyon and that ejidatarios manifested their agreement in an assembly. However, the alleged assembly was not performed; rather, the ejido representatives that were in office in 1947 were co-opted for the transfer to be legal. Most ejidatarios didn’t understand and weren’t aware of the implications of this exchange until 1979. In 1980 they presented an appeal to the Agrarian Department and it was not until 1987 when the ejido authorities received the document where they were given the ruling in favor of the appeal requested. Therefore, they had the legal recognition again as owners of the 179 hectares traded. From the perspective of the former president of the ejido commission in charge in 1980, who also underwent the appeal process, the person interested in the Tolantongo canyon was the front man of a former governor. Thus, “the transfer was a huge problem; it was about the caves that are the life of the people” (Mr. Abram, interview January 28, 2012). The second fact has to do with a businessman who visited the Tolantongo canyon in 1995 accompanied by the governor in office. This businessman expressed to some ejidatarios that he had the intention of investing in the canyon and working in a joint manner with them. The ejidatarios carried out an assembly that same year where they reached the agreement of rejecting the proposal because according to them, they would have to share the decisions and income from the caves with an external person.

In 1995, official delegates from the Ministry of Tourism (Secretaría de Turismo, SECTUR) and the Ministry of the Environment, Natural Resources and Fishing (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca, SEMARNAP), at the time, suggested to the ejidatarios the integration of Tolantongo into a Natural Protected Area (Área Natural Protegida, ANP). The ANP is part of one of the strategies for environmental conservation in México and since the 1990s a growth of these spaces took place. According to Durand (2014), the expansion of the ANPs was produced right with the arrival of the Neoliberal policy and he highlights that 83 % of the biosphere reserves in the country were established between 1990 and 2010. In addition, as Paz (2008) mentions, these zones are generally under regimes of social communal or ejido land ownership and whoever resides in them are owners by law, both of the territory and of the resources. In this way, ejidatarios from San Cristóbal had to be consulted, but in the assembly they agreed that Tolantongo would not be part of the ANP. From their perspective, they foresaw a decrease in the autonomy of various community spaces (decision making, management and distribution of resources, access to the caves) and possible conflicts with other communities involved. In this regard, an ejidatario expressed at the time:

They insisted so much that they would support us, that they would change the view of this so that it would be well-conserved, but what we would have would be only employment, not ownership; we would always have employment as long as we were responsible. We are experiencing that as it is, we are regulated here by internal norms: we do not need for others to apply it on us, we apply it ourselves. Not even firewood could be touched, that we could go in, but with permission. “Wait a minute! Why would they limit our spaces for us?” And we said no. (Mr. Rodríguez interview, December 1, 2011).

When recalling these facts, the president of the ejido’s Vigilance Council in 2012 stated:

We refused because it would limit us, we wouldn’t be able to even enter. It would take that part of the land and, if we wanted to enter, we had to ask for permission. We didn’t like that. We said: why are we supposed to ask for permission if it is ours? How are they going to limit us? We started working with our own means: we had already been doing it since before. It has always been the custom and we clung to not accepting and we have put in the work, and we have made it (Mr. Cruz, interview, September 27, 2011).

In the ANP project, a discourse of protection of the environment and endangered species was used. Therefore, the ejidatarios suggested that in place of the Tolantongo caves, another part of the ejido could be considered, where the “old man” cactus is abundant. Likewise, they expressed that they could also take care of the environment and that they were willing to receive training for it. However, the ejidatarios argued that the offer of the cacti was rejected because the sight was set on the caves, and that was where “the business” was found. This denotes not only a rejection to this strategy of environmental conservation by the Mexican State or Neoliberal conservation, but also a defense of the territory. As Rubio (2006:1052) states, the territory is the most visible unit of the rural world and its struggle “expresses the contradiction between global capital and the inhabitants of a region over the place of survival, the right to become integrated and to decide on their forms of government”.

After the ejidatarios objected to the ANP project, some were called to certain government offices at the beginning of 1996. In this meeting, they were questioned about their refusal to the federal and state governments’ offer; they were told that their attitude signaled that they didn’t need anything from the government. “They told us that we practically didn’t need support and that we shouldn’t even ask for it, because we were not going to get any” (Mr. Rodríguez, interview December 20, 2011). This discrepancy with the public officials generated some fear that there would be retaliation against the ejidatarios and the possibility of expropriation, even without their consent. About this situation, an ejidatario manifested:

We began to worry a lot about being evicted, in many places they have done that, they have gone in, they have fenced them in (the inhabitants), and they have kicked them out however they can. They insisted so much that we even got angry with a person from tourism; they wanted to mix us up and confuse us with their arguments (Mr. Ávalos, interview January 25, 2012; parentheses by the author).

One of the immediate strategies by the ejidatarios was the configuration of the Tolantongo Caves Ejido Cooperative Society (Sociedad Cooperativa Ejidal Grutas Tolantongo, on August 31, 1995). In 1998, the Ministry of Internal Revenue and Public Credit (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, SHCP) formally recognized the existence of the cooperative (Monterroso and Zizumbo, 2006). Also, the fact of becoming constituted as a cooperative legitimized in front of external agents their ownership and control of the caves. In face of this, it should be highlighted that the ejido does not grant property, but rather the usufruct over the lands granted and any additional formation within the legality of the State consolidates this ownership and control. In accordance with this, an ejidatario stated: “we became an ejido cooperative society: ejido and cooperative are two spaces that cannot be brought down by anyone, not even the government” (Mr. Ávalos, interview January 25, 2012).

Since those confrontations with the state government, during some time the ejidatarios did not go to the state offices to negotiate supports for the community and the ejido. For this purpose, they would resort to other sources; however, the ejidatarios pointed out that when the state government found out about these projects, they would be cancelled. It was not until 2007 when the relationship was renewed; even after that year, the governors and federal officials of the Ministry of Tourism (Secretaría de Turismo, SECTUR) and from the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, CDI) have visited the caves and have announced important projects for tourism in Valle del Mezquital. In this sense, an ejidatario mentioned: “The government had us in its sight, but we have achieved many things on our own, and this allows us to speak face to face to the government” (Mr. Ávalos, interview January 25, 2011).

Among the explanations of why the interests could not be reconciled between the government and the ejidatarios about this conservation policy of the ANP, or as Paz (2008) calls it, public and collective interests, in the first place there is that the ejidatarios had recognized the growing attraction and commercial value of the Tolantongo canyon from external agents. This fact had antecedents, particularly with the expropriation of the caves through the exchange and the intentions of the private investor accompanied by the governor in office in 1995. In second place, the way which the ANP was to be instituted, one of its principles was that it would be a development pole for local inhabitants and that they would be involved in its management. When this proposal arrived to San Cristóbal, the tourism project was already in motion with the participation of ejidatarios, who had already begun to see economic gains. Therefore, the official recognition of the canyon did not convince the ejidatarios that this participation would be maintained under their organizational principles. In fact, Durand (2014) shows how some experiences (like the Punta Laguna Reserve and Holbox Island in Yucatán) that began as local initiatives and later sought their official decree as ANP generated displacement of local groups and preeminence of external actors in the management. In third place, which is the most relevant aspect, is the permanence of a community organization derived from elements that Paz (2008:65-66) also highlights in his research: land ownership, institutions and organizational forms that result from it, validity of internal norms that are collectively sanctioned, distribution of power and material and symbolic valuation of the resources. To this, we must add the system of community governance, which explains the presence of spaces like the assembly, the cargo system, the communal tasks, the relationships of cooperation, and a rationality that is not entirely circumscribed to individualistic and capitalist relations. Likewise, we observe the existence of internal regulations that have collective recognition and legitimacy, additional membership modes to the ones established, and a revaluation of the lands by prohibiting their sale to external people.

By being constituted as a cooperative society and founding a tourism project, the ejidatarios also must adapt within an institutionalization and entrepreneurial management process; in face of this, they cannot avoid the issues of the market and the state structures. Among these actions, the following stand out: creation of their web page (http://www.grutastolantongo.com.mx), expansion of their touristic attractions, construction of infrastructure, training for some certifications related to service quality, food cleanliness and hygiene (M de Moderniza, Punto Limpio from SECTUR, Bandera Blanca from the State Ministry of Hidalgo). Currently, the cooperative society has, among others, four hotels, three restaurants, six cafeterias, 12 stores, five cocktail bars, and one torta shop. In contrast with other places where tourism is seasonal, in San Cristóbal it is permanent (with periods of low and high attendance), which is why the economic income of the ejidatarios depends basically on this activity and not on migration any more, or rainfed cultivation. The type of tourism practiced in San Cristóbal has it complications; it could not be understood only by this normative view of community-based tourism, or as part of the Neoliberal conservation imposed without questioning or derived from a governmental policy that drove alternative tourism in the 1990s in México. The literature about tourism experiences (Ludger and San German, 2012; Guzmán et al., 2013; Durand, 2014; Palomino et al., 2016) shows that the social realities of numerous rural communities are also forged by power relations and conflict of interests. Therefore, the fitting out and management of tourism initiatives are produced in socially and politically complex scenarios. Likewise, the success not only depends on the natural or cultural attraction, but also on some socio-organizational conditions (social capital, local entrepreneurial capacities, systems of community governance, availability of capital and workforce). In the case of San Cristóbal, in addition to its natural attraction, there are these socio-organizational conditions, but as we will see further on, there are certain ambiguities particularly about class and gender. This situation makes more complex the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion of members from the community.

Organizational characteristics and effects of the tourism project

In this document, we maintain that one of the key elements that explain the business of the Tolantongo caves is the community governance system expressed in the assembly, cargo system, and communal tasks. The community assembly in San Cristóbal is made up of ejidatarios and avecindados, and it coexists with the assembly of ejidatarios (integrated only by ejidatarios). These assemblies are carried out monthly, but there are also extraordinary ones celebrated; in these spaces representatives are not allowed, unless the absence is justified. The ejidatarios and avecindados have, in theory, voice and vote in community issues and in the election of authorities like those in the delegation and some committees. In themes related to the cooperative society, the avecindados do not have any intervention faculty. Therefore, the assembly of ejidatarios is the one that determines the community organization, to a large extent; in addition, of the total assemblies celebrated per year, most have to do with the cooperative society. The assembly has played a very important role in the different stages of the tourism project and its weight continues to be defining. In this sense, the decisions on the cooperative society always go through the agreement of ejidatarios with formal agrarian rights and those who were recognized by merit. Among the functions of the assembly, the appointment of positions of civil, religious and agrarian representation that each ejidatario undertakes stands out, as well as those of employment within the cooperative society.

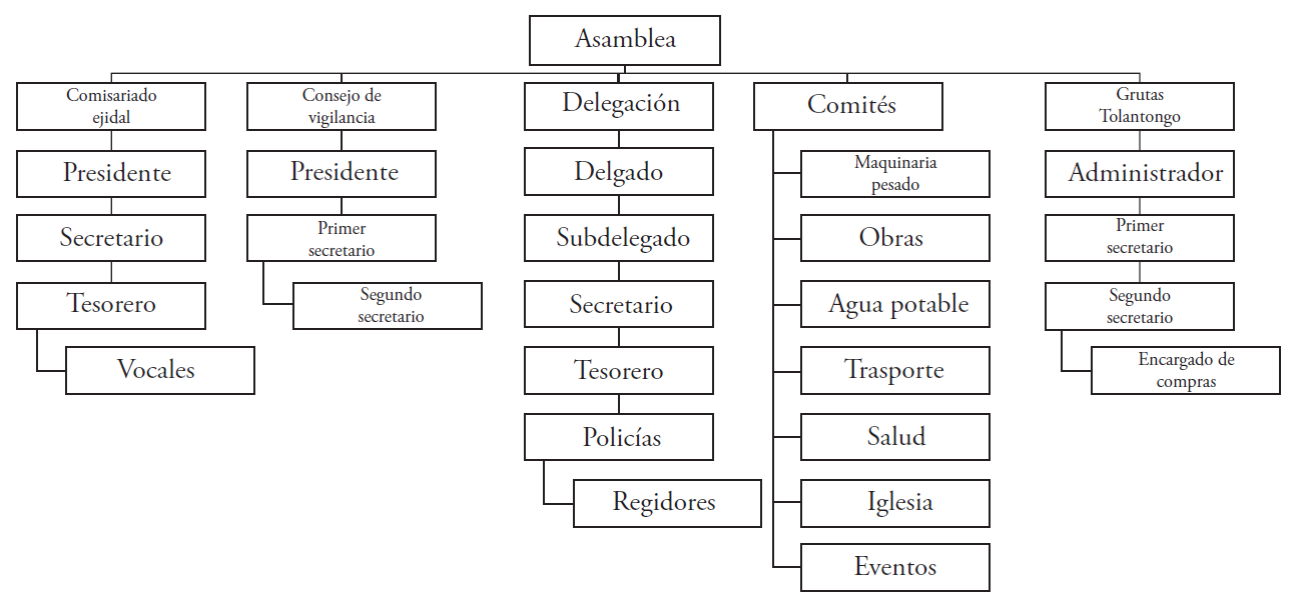

In terms of civil posts (although there are also religious), before the ejido endowment there was only the figure of auxiliary judge (today delegate) with these members: owner, deputy, policemen and councilor). As the ejido was formed, the cooperative society arose, the community grew and the committees multiplied (Figure 2). In addition, elements were added to the delegation such as the secretary and the treasurer, as well as the ejido authorities. The posts that both ejidatarios and avecindados should aspire to are the delegation and the committees; meanwhile, the management of the Tolantongo caves is for formal and informal ejidatarios and the ejido positions are only for the first. The figures of greatest weight in San Cristóbal are the ejido commissary, the administration of the Tolantongo caves and the delegation. All of these are agreed to in the assembly and their duration depends on the position; those who are appointed gather as main characteristic the experience of having exercised a prior post. Before, they were honorific, but since 2006 economic payment is given, with the aim of those who are in charge of these positions to be devoted full-time. Likewise, in recent years the posts of the delegation have been reserved only for formal ejidatarios and by merit.

The administration is the space that manages the Tolantongo caves; in this sense, the ejidatarios appointed for this position should carry out entrepreneurial functions, although they don’t necessarily have this training (older ejidatarios did not conclude primary education). These members provide inputs to the shops, hotels, restaurants, kitchens, among others, and negotiate prices with the suppliers, gather the earnings generated and those reported to the ejido treasury. Likewise, it is in charge of hiring employees and the tasks they will perform. However, the role that each partner performs in the tourism project (reception, responsible for kitchens, restaurants, ticket booths, cocktail bars, shops, lifeguards, among others) is established by the assembly. In face of this, the function of the administration is constrained, based on what the assembly dictates.

The communal tasks are carried out every Tuesday by ejidatarios or avecindados; in average, each ejidatario must perform 48 tasks during the year. Meanwhile, the avecindados are responsible for at least 18 tasks (sometimes on Tuesdays or other days of the week); a good part of them are carried out in the block of El Centro and Tolantongo. The tasks are not paid with money; the ejidatarios and avecindados can only send substitutes up to six times. Sending in allowed representatives should also not be done in a consecutive way, but rather in a tiered manner throughout the year. In the case of some ejidatario or avecindado not complying with what is established, he receives some sanctions (losing profit sharing if he is an ejidatario, access to a garden if he is avecindado). This collective work has also been conclusive in the constitutions of the tourism center (opening the dirt road) and continues to be in building its infrastructure and introducing services. Until 2017 the communal tasks had not become monetarized, which could be done, given the economic resources that they have now. In this regard, the most recent administrator mentioned:

“it is a custom that comes from our parents and grandparents; they used to do that… it keeps us as a group, unites us. It is about each one offering personally their work; I also do my tasks and that’s when we take advantage of the time to communicate some issue, and the same the commissary, the delegate or the security guard” (Mr. Fidencio, interview January 17, 2017).

In terms of the effects from the tourism project, two spheres are observed at the individual and community level. The 140 partners have unlimited benefits; the most outstanding are the annual profit sharing (they share 50 % with whoever inherited them the succession), bonus, payment for medications and health services, economic stimulus, entrepreneurship of two private businesses inside the tourism center, compensation when the society is withdrawn, and permanent employment. These employment positions are appointed in assembly and rotated annually, and built one of the outstanding elements of the organization because it allows each partner to have the possibility of serving in each position and to understand how it functions; the existence of lifelong leaders is avoided and resource diversion is controlled. In sum, in addition to being democratic, the rotation system constitutes a permanent mechanism of formation and training of the staff, so that all partners have enough knowledge in order to control those who exercise the positions of greater responsibility. Therefore, accountability has its foundation on the broad knowledge which is product from the experience. The ejidatarios that entered by merit receive the same benefits, although in a progressive way until having seven years of tenure within the society. Those ejidatarios who did not leave successors receive a monthly pension from the cooperative society (it exceeds what the federal government hands out through the program 65 y más) and medical assistance. Likewise, in the case that an older ejidatario does not have family descendants or if he does and nobody takes care of him, the community authorities also take charge of his care. In relation to other residents, in the community they have free access to the facilities of the tourism center, employment, and support for funerary expenses. In addition, together with the partners of the Tolantongo caves, they converge in two events: “Mother’s Day” and “Father’s Day”. In both celebrations, the cooperative society prepares a meal for them and an economic stimulus is given.

At the community level, the cooperative society has extended its role from administrator to executor of infrastructure works (pavement, sports courts, school remodeling, health services, church building, among others) and services for the benefit of all members of the community (such as the transport system to take students to the nearest high school). In the symbolic scope, the Tolantongo caves also participate in the financing of San Cristóbal’s patron saint’s festivity (they are also in the process of building their church), considered as one of most sumptuous of the municipality of Cardonal. Therefore, welfare is observed that transcends the economic and individual sphere, to include other dimensions like a collective and symbolic welfare. Likewise, the presence of social relations that are not completely reduced to commercial issues, as is the case of the communal tasks, where up until today the physical work is prioritized and monetary payment is not allowed. Some of these elements, as we have seen, are considered to be parts of alternative development.

From these same income from the tourism project, other alternative businesses began to be created (water purifying plant, paddock, aquaculture farm, collective transport network, maguey production, heavy machinery, exploitation of the marble mine), some of which supply inputs to the tourism project. Therefore, the incomes no longer depend only on the natural resources of the community. It should also be highlighted that since 2005, the return of national and international migrants was fostered, particularly of the children of ejidatarios. This was the result of reforms in the regulations where it was indicated that the entry of ejidatarios from work and service would be up to 25 years of age, with the goal of establishing an equitable standard of labor between natives and migrants. Since then, men whose age approached 25 years have been returning; likewise, many of these migrants have been placed in strategic spaces of the tourism center (hotels and restaurants). It is undeniable that the tourism project has stopped migration and that the tourism center has been an important space in the “reintegration” of returning migrants. Although in México this return migration responded to a structural situation (economic crisis in the United States in 2007), in the case of San Cristóbal it was also due to a local issue. According to the members of the 2017 administration, most of those who were in the United States have already returned to the community.

The cooperative society also supports other neighboring communities, whether by sponsoring some events or granting them an economic benefit in their infrastructure works. Likewise, they give free entry when a school requests it; in addition, some of the employees are not originally from San Cristóbal, but rather from nearby localities. The main route to San Cristóbal is the México-Laredo highway and in the municipality (Ixmiquilpan), near Cardonal, there are various businesses for tourism, as well as in the localities neighboring San Cristóbal. During Easter Week, which is the time of greatest tourism turnout, it is common to see provisional spaces where barbacoa, pulque and handcrafts are sold. Therefore, the impact of the tourism center goes beyond the confines of San Cristóbal and it is seen that tourism represents a very important source of incomes in Valle del Mezquital (region which, according to the State Association of Health Spas and Hot Springs of Hidalgo, concentrates more than 50 % of tourism businesses of health resorts and hot springs).

Previously, we have said that some social relationships produced in San Cristóbal go beyond the economic dimension of development. Likewise, the geographic landscape of the locality shows that the level of income and material goods of the ejidatarios differs from what is observed in other localities of the municipality of Cardonal. Here is where sumptuous buildings of common use stand out, such as the church and ejido auditorium, but also the households of the ejidatarios themselves. This perspective does not fit the traditional definition of what is rural, all the more since ejidatarios are no longer just devoted to land cultivation. Therefore, I agree with Grajales and Concheiro (2009) regarding the need to move beyond a sectorial definition of the rural scope and transit towards a territorial viewpoint. This means observing the productive heterogeneity and socio-spatial reconfiguration of the territory, but especially the modes of appropriation of the territory that subjects undertake.

The assembly, the posts and the communal tasks are articulated for the organization of communal life and the tourism project. However, this concatenation is complex and the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion between ejidatarios, formal and informal, and avecindados is not entirely defining and has its paradoxes. In recent years the regulations underwent some modifications; among them, the fact that ejidatarios with documents and without them can only name two of their children to enter the cooperative society. The central argument was that in the future too many partners would decrease the amount of profit received; another relevant change was that the daughters of ejidatarios would not only be able to enter by succession, but rather also by merit. The reason for this is that several ejidatarios didn’t have sons and would generally leave the succession to a male relative. From my point of view this represents a substantial change, for it was formally recognized that the service and work of women can also be valued for their entry into the cooperative society. These reforms in the regulations have generated tensions, since a good part of the ejidatarios who approved the reforms have retired, and their descendants do not necessarily agree with their predecessors. For example, some ejidatarios with documents have expressed that they should have the right for all their children to enter the cooperative society and not to be limited to two because they do have the “papers”. In this regard, a dispute arises between the “legal” and community recognition. In addition to this, the case occurred of women requesting their entry by merit, but the assembly not being able to resolve this request; according to some ejidatarios there were positions in favor and against, and the decision was postponed. Within families, the decision of which of the children would be the successor has also generated harshness between siblings. In the field work I observed that this post was generally inherited to the youngest son by custom, but some ejidatarios were opting for granting the succession to whoever had reached 25 years of age or who didn’t have professional studies. Finally, the avecindados, who in principle ought to have space for the delegation positions (an essentially communal post), are recently not considered any more. These functions of the delegation have been restricted to ejidatarios; the avecindados are given priority for the employment spots in the tourism project. Even if it is an ejidatario, the delegate represents the whole community; he meets with the ejido commissary, the vigilance council, and the administrator on weekends and, jointly, they visit the facilities of the tourism project. In parallel, he also leads the patrol’s vigilance spots and the community policemen, coordinates the calls to communal tasks, and must respond to the demands from other members of the community.

Conclusions

In this text, the experience of a proposal of alternative development and community-based tourism set forth by the inhabitants of San Cristóbal has been documented. The particularity of this case lies in that the promotion of touristic activity was their decision and did not necessarily respond to the conjunction of the height of alternative tourism in the 1990s and Neoliberal conservation. The ejidatarios have had support from State agencies such as the Indigenous Patrimony of Valle del Mezquital (Patrimonio Indígena del Valle del Mezquital, PIVM) and other ministries, but they have maintained autonomy in the organization and administration of their tourism project and have a capacity of negotiation with external actors. In fact, the ejidatarios pointed out that the support they receive from the government for community infrastructure is minimal. On the other hand, although their natural resources are commercialized under the capitalist logic, they continue to be common patrimony. To reach this, some factors were conjugated; first, a collective awareness of what it means to be the owners of the Tolantongo canyon and of the economic benefits that their tourism project generates. This process of appropriation of natural resources was strengthened since the dirt road was completed in the 1970s, when tourism increased and economic incomes were received. Secondly, the presence of social cohesion product of institutions like the assembly, the communal tasks and the posts that provoked the resistance, struggle and confrontation over the Tolantongo canyon, in face of private interests and public interests. This also explains why they opposed selling their lands to external people, despite them being able to because of modifications to the agrarian reform.

As result, there is an organization that shows, among other things, the different channels of communication present between the ejido authorities, delegation and various committees, the accountability, the exercise of posts, the maintenance of the tasks with physical work, informal mechanisms to consider other people as ejidatarios. In this way, the tourism project functions by combining entrepreneurial needs and an ancestral communal organization that survives. In addition, the development model in San Cristóbal resembles the principles of alternative development and community-based tourism where a community is the basis, as well as the participation of local inhabitants, local control of the resources, and a nexus between the economic and social spheres, among others. On the other hand, the impact that tourism generates in the community and beyond its limits is extraordinary and more incomes have been generated with other businesses, for there is the advantage that tourism is permanent. In San Cristóbal there are also some contradictions and they represent future challenges; among these, gender and class, the potential use of local professionals, and environmental conservation and interaction with tourists. The regulations have already established formally that women can be ejidatarios by succession and also by merit; however, as we have mentioned, the entry of women by the latter means still faces resistances. Concerning the avecindados, there are some voices that request that they be considered to be part of the cooperative society. Presently, young professionals that enter the cooperative society are already placed in positions for which they have studied, but harshness is detected between ejidatarios with professions and those without. Regarding the environmental issue, the ejidatarios tend to speak of ecotourism and they comply with some environmental care actions. However, there are divergences between those who want to build more infrastructures in the canyon and those that defend that they should be over those ambitions and conserve the natural attractions. This finding agrees with what Palomino et al. (2016) presented, where they found that most of the community-based tourism businesses in the country have an absence of environmental management to ensure the sustainable use of natural resources. On the other hand, given the workload of ejidatarios, the interaction of a more cultural nature with tourists is also minimal. Finally, the tourism project in San Cristóbal reflects the persistence of communal principles in face of this incursion of ejidatarios as entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, Hugo, y María Cristina Velásquez. 2008. La comunalidad: un referente indígena para la reconciliación política en conflictos electorales municipales en Oaxaca. In: Xóchitl Leyva, Araceli Burguete y Shannon Speed (coords), Gobernar (en) la diversidad: experiencias indígenas desde América Latina. Hacia la investigación de Co-labor, 393-432, México, CIESAS, FLACSO. [ Links ]

Albo, Xavier. 2011. Suma Qamaña=convivir bien ¿Cómo medirlo? In: Ivonne Farah H. y Luciano Vasapollo (coords), Vivir Bien: ¿Paradigma no capitalista? 133-134, La Paz Bolivia, CIDES, 2011. [ Links ]

Bonfil, Guillermo. 1995. El etnodesarrollo: sus premisas jurídicas, políticas y de organización. In: Obras escogidas de Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, Tomo 2, 464-480, México, INI/ INAH/CIESAS/CNCA. [ Links ]

CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de población). 2012. Índices de intensidad migratoria, México Estados Unidos 2010, México. [ Links ]

Durand, Leticia. 2014. ¿Todas ganan? Neoliberalismo, naturaleza y conservación. Sociológica, año 29, Núm. 82, mayo-agosto de 2014. [ Links ]

Farah, Ivonne, yLuciano Vasapollo . 2011. Introducción. In: Vivir Bien: ¿Paradigma no capitalista? 11-38, La Paz Bolivia, CIDES-UMSA/SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÁ DE ROMA /Oxfam. [ Links ]

Fernández, María José. 2011. Turismo comunitario y empresas de base comunitaria turísticas: ¿estamos hablando de lo mismo? El Periplo Sustentable, Núm. 20 enero-junio 2011. [ Links ]

Garduño, Martha, Celia Guzmán, y Lilia Zizumbo. 2009. Turismo rural: Participación de las comunidades y programas federales. El periplo sustentable. Núm. 17. [ Links ]

Grajales, Sergio, y Luciano Concheiro. 2009. Nueva ruralidad y desarrollo territorial. Una perspectiva desde los sujetos sociales. Veredas. Núm. 18, México, 2009. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2011. Buen vivir: germinando alternativas al desarrollo. In: ALAI otro desarrollo América Latina en Movimiento, en In: ALAI otro desarrollo América Latina en Movimiento, en http://www.globalizacion.org/analisis/GudynasBuenVivirGerminandoALAI11.pdf (consultado el 6/diciembre /2011). [ Links ]

Guzmán, Mauricio, Fernanda Figueroa, y Leticia Durand. 2013. Ecología política y ecoturismo en México: reflexiones desde la Huasteca Potosina y la Selva Lacandona. In: Guzmán Mauricio y Juárez Diego. En busca del ecoturismo. Casos y experiencias del turismo sustentable en México, Costa Rica, Brasil y Australia, 17-28, México, COLSAN. [ Links ]

Hettne, Bjorn. 1990. Development Theory and the Three Wordls, New York, Harlow Logman, Development Studies. [ Links ]

Korsbaek, Leif. 1996. Introducción al sistema de cargos, (Antología), 16-34, México, UNAM. [ Links ]

López, Gustavo, y Bertha Palomino. 2008. Políticas públicas y ecoturismo en comunidades indígenas de México. Teoría y Praxis, Núm.5. [ Links ]

Ludger, Brenner, y Stephanie San German. 2012. Gobernanza local para el ecoturismo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, México. Alteridades, vol.22, Núm. 44. [ Links ]

Maldonado, Carlos. 2005. Pautas metodológicas para el análisis de experiencias de turismo comunitario. Organización Internacional del Trabajo. [ Links ]

Mendoza, Silvia. 2007. Del gran jefe a los pequeños hombres. Poder local y comunidad indígena en el municipio de Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo, Tesis de doctorado, el Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Monterroso, Neftalí, yLilia Zizumbo. 2006. La reconfiguración neoliberal de los ámbitos rurales a partir del turismo: ¿Avance o retroceso? Convergencia, vol. 16, Núm. 50. [ Links ]

Palomino, Bertha, José Gasca, y Gustavo López. 2016. El turismo comunitario en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca: perspectiva desde las instituciones y la gobernanza en territorios indígenas. El Periplo Sustentable , Núm. 30 enero-junio-2016. [ Links ]

Paz Salinas, María Fernanda. 2008. De áreas naturales protegidas y participación: convergencias y diferencias en la construcción de interés público. Nueva Antropología, Vol. XXI, Núm. 68. [ Links ]

Rubio, Blanca. 2006. Territorio y Globalización en México ¿Un nuevo paradigma rural?, Comercio exterior, Vol. 56, Núm. 12, diciembre 2006. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Ella. 2012. Ciudadanía Comunal y patrimonio comunal indígena. El Caso del Valle del Mezquital Hidalgo. Ponencia presentada en el Tercer Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Sociales, UNAM, 26 de febrero al 1 de marzo. [ Links ]

Veltmeyer, Henry. 2003. La dinámica de la comunidad y las clases sociales. In: Henry Veltemeyer, y Anthony O’Malley (coords). En contra del neoliberalismo. El desarrollo basado en la comunidad en América Latina, 39-48, México, UAZ/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Veltmeyer, Henry. 2000. Latinoamérica: el capital global y las perspectivas de un desarrollo alternativo, México, UAZ . [ Links ]

Vergara, Leandro. 2011. Globalización, tierra, resistencia y autonomía: el EZLN y el MST. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, Vol. 73, Núm. 3, julio septiembre 2011. [ Links ]

1The interviews had the following themes: functioning of the community and axes of communality (assembly, communal tasks, and cargo system), migration, history of the development project, its organization and development model. On some occasions, themes arose that were not stipulated in the guide, but they were relevant for the research theme. These interviews were compared also with the evidence found in the literature and observation. Most of the interviews were recorded prior authorization from the respondents. Some people were interviewed only once, but in the case of the key respondents they were interviewed more than once.

Received: May 01, 2016; Accepted: December 01, 2016

texto en

texto en