Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.15 n.2 Texcoco Apr./Jun. 2018

Articles

Production of the Escamol Ant (Liometopum apiculatum Mayr 1870) and its Habitat in the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau, México

1Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potosí. México. (benjamin@colpos.mx; pineda.francisco@colpos.mx; ltarango@colpos.mx)

2Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. (saulu@colpos.mx)

3Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo. México. (gramirez@colpos.mx)

4Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Córdoba. México. (fkatia@colpos.mx).

The escamol ant (L. apiculatum Mayr) is important economically for rural communities. In four localities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau, escamol ant nests were identified and their yield was determined, as well as their relation to the habitat and the population size of their colonies during the 2010 harvest of escamoles. In the nests registered the following variables were evaluated: condition of the nest, quality of the nest, amount of ants (scarce, regular and abundant), type of nesting substrate, and escamol yield. The condition of the nests was compared through Indexes of Relative Abundance, Relative Density. To determine the association between quality of the nest and amount of ants, the Observation Frequencies (OF) were used, and the independent contingencies tables of x 2. To determine the effect of the nesting substrate and the escamol yield (clean weight in g), ANOVA was performed. Seventy-seven (77) nests were found; the condition of the nest that predominated was “disturbed” (79 %), with an average relative density of 4.14 nests km-1. The OF and the x² analysis identified a higher relation (3.47) between scarce amount of ants-bad quality and regular amount of ants-very good quality (2.06) of the nest (p=0.001999). The ANOVA identified a relationship between the nesting substrate and the escamol yield (p=0.0013), with a higher yield in the nopal nesting substrate (36 %).

Key words: xeric scrubland; preference; nesting substrates

La hormiga escamolera (L. apiculatum Mayr) es importante económicamente para las comunidades rurales. En cuatro localidades del Altiplano Potosino-Zacatecano, durante la recolecta de escamoles 2010, se identificaron nidos de la hormiga escamolera, y se determinó su rendimiento, su relación con el hábitat y su tamaño poblacional de sus colonias. En los nidos registrados se evaluaron las variables: condición del nido, calidad del nido, cantidad de hormigas (escasa, regular y abundante), tipo de sustrato de anidación y rendimiento de escamol. La condición de nidos se comparó mediante Índices de Abundancia Relativa, Densidad Relativa. Para determinar la asociación entre la calidad del nido y la cantidad de hormigas se utilizaron las Frecuencias de Observación (FO) y tablas de contingencias independientes de x 2. Para determinar el efecto del sustrato de anidación y el rendimiento del escamol (peso limpio en g) se realizó un ANOVA. Se registraron 77 nidos; la condición del nido que predominó fue la “perturbada” (79%), con una densidad relativa promedio de 4.14 nidos km-1. Las FO y el análisis de x² identificaron una mayor relación (3.47) entre una cantidad de hormigas escasa-mala calidad y una cantidad regular de hormigas-muy buena calidad (2.06) del nido (p=0.001999). El ANOVA identificó una relación entre el sustrato de anidación y el rendimiento de escamol (p=0.0013), con un mayor rendimiento en el sustrato de anidación nopal (36 %).

Palabras clave: matorral xerófilo; preferencia; sustratos de anidación

Introduction

Insects are a very diverse taxonomic group, and more than one million species identified in the world are mentioned (Engel and Grimaldi, 2004), which vary in shapes, sizes and colors (Lokeshwari and Shantibala, 2010); many of them are used for their commercialization as pets (Villegas et al., 2005). However, these are also used for human consumption (Costa-Neto, 2002). Between 535 and 549 edible species have been recorded in México, which are commercialized in the center, south and southeast of the country, reaching high prices as gourmet dishes (Ramos-Elorduy and Pino-Moreno, 2005; Costa-Neto and Ramos-Elorduy, 2006; Ramos-Elorduy et al., 2008). The orders with species of highest consumption are: Hymenoptera, Orthoptera, Hemiptera and Coleoptera; they also constitute means of identity among different ethnic groups.

The Hymenoptera order includes ants from the Formicidae family, whose diversity is determined by the latitude and altitude (Kusnezov, 1975). The greatest distribution of ants takes place in tropical and subtropical forests of low altitude, as well as in the warm deserts throughout the world (Brown et al., 1973).

An important species of the Formicidae family is Liometopum apiculatum, of which the larvae and pupae from its reproductive phases (drones or princesses), known as escamoles, represent economic and dietary incomes for the rural communities (Ramos-Elorduy et al., 1984; Dufour, 1987; Ramos-Elorduy, 1991; 2005; 2008; Ramos-Elorduy et al., 2006). In the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau, this species also represents an important economic income and it is collected in a traditional manner during March and April and, occasionally, until May, depending on the temperature and the precipitation (Cuadrillero-Aguilar, 1980; Ramos-Elorduy et al., 1988; Velasco-Corona et al., 2007). Some authors report that this resource is taken advantage of in variable amounts, which range from 137 g to 3 kg per nest (Ramos-Elorduy et al., 1986; Ambrosio-Arzate et al., 2010; Cruz-Labana et al., 2014).

However, despite its economic and dietary importance, and ecological role, L. apiculatum has been scarcely studied. Recent studies refer to the ethno-entomology that rural communities have with the ant (Dinwiddie et al., 2013), its biology (Lara-Juarez et al., 2015), the habitat components that explain the presence of the ant (Cruz-Labana et al., 2014), and even their trophobiotic relation with other insects (Velasco-Corona et al., 2007), and none explain how the size of the colony and the nesting substrates affect their production. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to compare the yield of nests (disturbed vs conserved) and to determine how the population size of the escamol ant and the nesting substrate affect the yield of escamoles, and the nest quality of Liometopum apiculatum in four communities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau.

Methodology

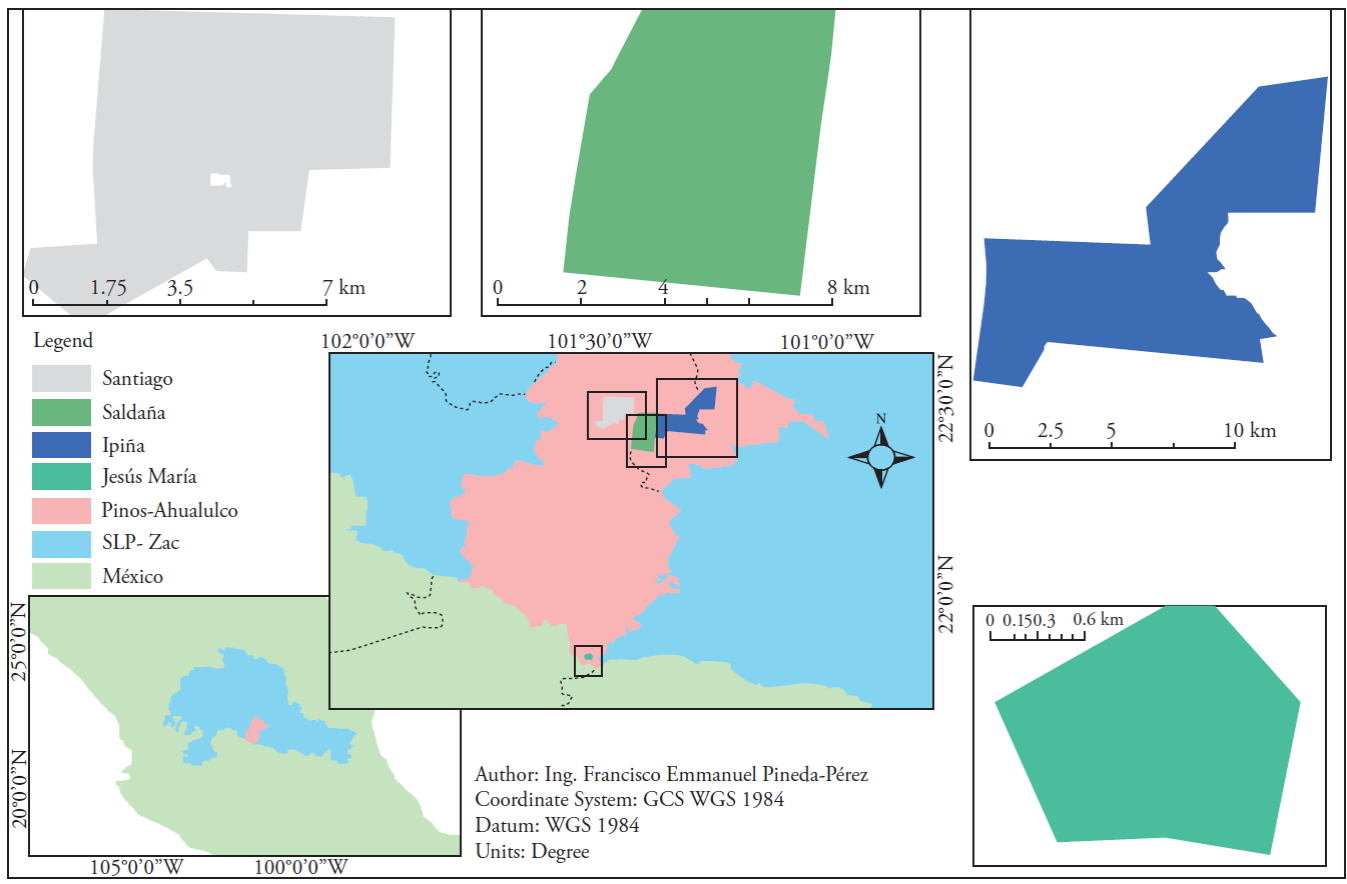

This study was carried out during the period of escamol harvest (March and April) of 2010 in four communities of the municipalities of Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí, and Pinos, Zacatecas (Figure 1). The seats of those municipalities are located on coordinates 22° 24’ N, 101°10’ W and 22° 16’ N, 101° 34’ W. Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí, has an average altitude of 1850 m and Pinos, Zacatecas, of 2419 m. According to García (1998), the climate for both municipalities corresponds to semi-arid temperate (BS1kw) and the vegetation, in majority, corresponds to microphyll, crassicaule and rosetophyll, with some grassland zones (Rzedowsky, 1978; Rzedowsky and Huerta, 1994).

Figure 1 Communities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau: Ipiña, Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí; Jesús María, Saldaña and Santiago, Pinos, Zacatecas.

In the four communities selected for the escamol collection of L. apiculatum and to locate colonies and nests of the escamol ant, a systematic sample was carried out. This consisted in performing visits to the communities selected in a schedule of 6:00 to 16:00 hours with the support of a collector guide, and taking into account the traditional technique used by escamol collectors in the zone, which consisted in: a) searching for the foraging paths of the ant; b) locating the nest in the path intersection; and c) excavating and extracting the escamol. Once the escamol was extracted, it was sieved, washed and weighed.

For each nest, the following variables were recorded: nest condition (disturbed vs conserved) which was determined based on its state of conservation; nest quality (very good, good, regular, bad and very bad, characteristic determined based on the prior exploitation of the nest); amount of ants (scarce, regular and abundant), type of nesting substrate and escamol yield (g). The amount of ants from the colony was quantified visually. Likewise, for the nests found their UTM coordinates were recorded with a Global Positioning System. With this information the reference points of each nest were created, and the map of their localization was elaborated with a Geographic Information System (GIS) in the ArcGis 10.1 software (ESRI, 2012).

In order to determine the abundance of nests, the Relative Abundance Index (RAI) was used (Jenks et al., 2011), with modifications for this study: RAI=(Ncond/NT)x100; where Ncond: number of nests with a certain type of condition, NT: total number of nests. To obtain the number of nests with different condition by community, the Relative Density (DP, for its initials in Spanish) of disturbed and conserved nests was defined according to the Hayne equation by bands (Martella et al., 2012) modified for this study. The equation that describes it is: DP=(1/F)x[Σ(z j/D j)]; where F: number of localities sampled, z j: number of nests with certain condition per locality, D j: distance of visit per zone. The software used to calculate this index was Excel 2013 (Microsoft, 2013).

To determine the frequency of nests with certain quality a trend-graphic analysis of Observation Frequency (OF) was carried out (Curts, 1993), modified as detailed next: OF=(No. of nests with many ants with certain quality / Total no. of nests with many ants)x100. To determine the association in function of the amount of ants and the nest yield, a x 2 contingency table was elaborated in terms of its quality, using the standardized values as level of association. Pearson’s square-chi statistic was obtained (Agresti, 2003) and the R-Commander software (R, 2014) was used to adjust the sample size, where the x 2 “test” was simulated in 2000 repetitions.

The information of escamol yield was homogenized to be able to use it in a qualitative way, where the clean weight of the escamol was categorized as scarce production and abundant production. For this, the weight of the clean escamol was classified as of low yield when its values were ≤ median and of high yield when its values were > median. The OFs were used to determine the preferences for nesting substrates of L. apiculatum.

To determine differences between nesting substrates, yield and nesting substrate, a analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used (Fisher, 1993; Molinero, 2003). For this analysis, the substrates were grouped into three categories: Nopal as “Substrate 1”, Maguey as “Substrate 2”, and garabatillo (Mimosa biuncifera), smooth mesquite (Prosopis laevigata), sweet acacia (Acacia farnesiana), yucca (Yucca spp.), garambullo (Myrtillocactus geometrizans), crucilla (Randia echinocarpa) and biznaga (Echinocactus spp.) were included in “Substrate 3”. The substrate variable was taken as any item in which the ant could place its nests. To avoid a bias from the size of the sample, a transformation of the response variable “Yield in grams (clean escamol)” into Ln (Natural Logarithm) was performed; for this purpose, the InfoStat v.2013 software was used (Di Rienzo et al., 2013).

Results and Discussion

In this study, 77 nests were found and evaluated in four localities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau (Figure 2). Of these, 16 presented a conserved condition and 61 were disturbed; the density of conserved and disturbed was 2.25 and 4.14 nests km-1, respectively. The production of those conserved was 543.1±-564.1 g and of those disturbed, 169.2±-301.0 g (Table 1). The density of conserved and disturbed nests was 2.25 and 4.14 nests km-1, respectively. Of the four localities, Ipiña, Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí, produced less escamol and the nesting substrate on which the escamol ant produced more escamol was “Nopal”. A low production of escamol and a high density of disturbed nests are indicators of the intensive use of this natural resource; therefore, a better control has been proposed, demanding legislation about the exploitation of the escamol ant larvae. There is insistence in the transference of knowledge and a better organization of the collectors for production (Ramos-Elorduy et al., 2006; Ambrosio-Arzate et al., 2010, Tarango-Arámbula, 2012).

Figure 2 Escamol ant nests in four localities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau; Ipiña (Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí); Jesús María, Saldaña and Santiago (Pinos, Zacatecas).

Table 1 Escamol yield per locality, nesting substrate and nest condition of Liometopum apiculatum Mayr.

| Localidad/Sustrato/ Condición | Promedio (g) | Desviación estándar |

|---|---|---|

| Ipiña | 169.2 | 308.3 |

| Nopal (Opuntia spp.) | 382.0 | 485.9 |

| Conservado | 1500.0 | 0.0 |

| Perturbado | 257.8 | 328.7 |

| Maguey (Agave spp.) | 104.4 | 188.3 |

| Conservado | 410.0 | 400.0 |

| Perturbado | 72.2 | 107.1 |

| Otros | 99.4 | 162.8 |

| Conservado | 505.0 | 0.0 |

| Perturbado | 58.8 | 105.1 |

| Jesús María | 349.4 | 276.7 |

| Nopal | 537.5 | 314.1 |

| Conservado | 537.5 | 314.1 |

| Maguey | 199.0 | 89.1 |

| Conservado | 199.0 | 89.1 |

| Saldaña | 345.7 | 203.8 |

| Nopal | 345.7 | 203.8 |

| Conservado | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Perturbado | 403.3 | 158.7 |

| Santiago | 333.0 | 585.7 |

| Nopal | 430.6 | 631.5 |

| Conservado | 1360.0 | 650.0 |

| Perturbado | 120.8 | 83.5 |

| Maguey | 84.7 | 77.7 |

| Perturbado | 84.7 | 77.7 |

| Otros | 1060.0 | 890.0 |

| Perturbado | 1060.0 | 890.0 |

| Total general | 246.7 | 398.1 |

| Conservado | 543.1 | 564.1 |

| Perturbado | 169.2 | 301.0 |

According to the t-Student analysis, statistically significant differences were found (p<0.001) between the production of escamoles from conserved vs disturbed nests (Table 2).

Table 2 Results from the t-Student analysis for the production of escamoles in conserved vs disturbed nests per locality and in general.

| Localidad* | Valor t | Prob. |

|---|---|---|

| Ipiña | -8.8292 | 4.96E-11 |

| Saldaña | -2.5 | 0.0465 |

| Santiago | -5.4571 | 3.49E-05 |

| Todos | -6.2786 | 1.94E-08 |

*No “disturbed” nests were found in the locality of Jesús María, so it was not included in the analysis.

The OFs identified a better quality of the nest when there was a regular amount of ants (63 %) and a bad quality of the nest with scarce amount of ants (100 %). This was confirmed through the analysis of the deviations from what was expected under standardized independencies of Chi-square, which recorded a strong association between a very bad quality of the nest with a scarce amount of ants (3.47) and a very good quality of the nest with a regular amount of ants (2.06) (p=0.001999) (Table 3).

Table 3 Relation between nest quality and amount of ants through the deviations expected under standardized independencies.

| Calidad del nido | Cantidad de hormigas | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Abundante | Regular | Escasa | |

| Muy mala | -1.55 | 1.11 | 3.47 |

| Mala | 0.87 | -1.66 | -0.74 |

| Regular | 0.54 | 0.47 | -1.10 |

| Buena | 0.50 | -0.76 | -0.65 |

| Muy Buena | -0.43 | 2.06 | -1.06 |

| Total | -0.07 | 1.22 | -0.08 |

The amount of L. apiculatum ants can reach 250 000 individuals per nest (Hoey-Chamberlain et al., 2013); however, an excessive increase of the population can cause a decrease in the nest quality, decreasing its productivity. This study only evaluated basic aspects such as the quality of the nest and its yield on the relationship of the number of ants and nesting substrates with the nest quality. However, the higher number of disturbed nests found in this study, which are associated with a low yield of escamoles (Table 1), suggests the need to undertake long-term studies that help to explain the factors that best define a higher production of escamoles.

The disturbance of ecosystems intervenes in the diversity of the habitat, particularly in the mirmecofauna of the site; for example, in very disturbed ecosystems the diversity of ants decreases and the species of generalist ants become established and dominate the populations of other species (Alfonso et al., 2010; Ruiz-Cancino et al., 2010; Tizón et al., 2010; Chanatásig-Vaca et al., 2011; Martínez et al., 2015). Cruz-Labana et al. (2014) performed a study of the escamol ant in a similar type of vegetation to where this research was developed, finding that the habitats that the escamol ant prefers are the ones moderately disturbed. Therefore, it is important to manage the habitat of L. apiculatum and their nests to avoid extreme variations in their population size that place the colony at risk.

The ANOVA found significant differences between the yield and the nesting substrate (F (2,2)= 7.55 p=0.0013). The “nopal” (36 %) nesting substrate produced a high yield, while the “maguey” substrate (54 %) indicated a low production; however, the substrate “others” participated more equitably in all the categories of yield (Table 1). However, it was observed that L. apiculatum produced more escamol on the “nopal” substrate and that this species could select nopal preferably to nest, as well as others do to select their foraging substrate (Stradling, 1978; Rojas-Fernández, 2001; Cortes-Pérez et al., 2003; Pirk et al., 2004), and nest in their different habitats.

It is quite likely that Liometopum apiculatum presents a similar pattern when associating to habitats with rosetophyll shrubs in arid and semi-arid zones of México (Esparza-Frausto et al., 2008; Cruz-Labana et al., 2014); however, they also seem to have plasticity on the use of different ecosystems as other authors report (Ramos-Elorduy et al., 1986; Velasco-Corona et al. 2007; Hoey-Chamberlain et al., 2013).

The escamol ant seems to present a pattern of higher productivity when associating to microphyll, rosetophyll and crassicaule shrubs, and, specifically, to larger vegetative structures such as nopal (Opuntia spp.), maguey (Agave spp.) and yucca (Yucca spp.) that offer potential nesting sites, for foraging, thermal protection, and the possibility of having inter-specific relations with other insects on which it feeds (Novoa et al. 2005; Velasco-Corona et al. 2007; Miranda et al. 2012). This can be explained with the study by Novoa et al. (2005), who found that Camponotus spp. prefers plant structures such as cactuses, attracted by their sugars and flower buttons.

Although the nesting substrates have an influence on the production of escamol, the longevity of the nest is also important, among other factors (Juárez-Sandoval et al., 2010). This study contributes basic information about some factors involved in the production of escamoles; however, to provide a better management of the escamol ant colonies and their habitats, it is necessary to understand the variables that best explain their presence; likewise, the real size of the nest and the colonies should be understood, as well as their patterns and foraging distances (González-Espinosa, 1984; Gómez and Espadaler, 1996; Jofré and Medina, 2012).

Conclusions

Seventy-seven (77) nests were found and evaluated in four localities of the Potosino-Zacatecano High Plateau. Of these, 61 presented a disturbed condition and 16 a conserved condition.

The density of conserved and disturbed nests was 2.25 and 4.14 nests km-1, respectively.

The nests with a conserved condition produced more escamoles (543.1 g) than those that were in a disturbed condition (169.2 g).

A strong association was found between a very bad quality of the nest with scarce quality of ants (3.47) and between a very good one with regular amount.

There is greater relation in the yield of trabeculae in function of a very good quality of the nest, associated when there is a “regular” amount of ants in it; contrary case, a bad quality is associated to a “scarce” amount of ants.

Of the four localities, Ipiña, Ahualulco, San Luis Potosí produced less escamol and the nesting substrate on which the escamol ant produced more was “Nopal”.

Literatura Citada

Agresti, Alan. 2003. Categorical Data Analysis Second Edition. New Jersey, USA, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Hoboken. 732 p. [ Links ]

Alfonso Simonetti, Janet, Yaril Matienzo Brito, y Luis L. Vázquez-Moreno. 2010. Fauna de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) asociadas a un sistema de producción agrícola urbano. Fitosanidad. Vol. 14, núm. 3. pp: 153-158. [ Links ]

Ambrosio-Arzate, Gabriela Alejandra, Rubén Nieto-Hernández, Sotero Aguilar-Mendel, y Angélica Espinoza-Ortega. 2010. Los insectos comestibles: un recurso para el desarrollo local en el centro de México. Spatial Dynamics in Agri-Food systems: Implications for sustainability and consumer welfare. Parma, Italy. [ Links ]

Brown, Jessi, Steve Vargo, Edward Connor, and Michael Nuckols. 1973. Causes of vertical stratification in the density of Cameraria hamadryadella. Ecological Entomology. Vol. 22, Num. 1. pp: 16-25. [ Links ]

Chanatásig-Vaca, Cristina Isabel, Esperanza Huerta-Lwanga, Patricia Rojas-Fernández, Alejandro Ponce-Mendoza, Jorge Mendoza-Vega, Alejandro Morón-Ríos, Hans Van Der Wal, y Benito Bernardo Dzib-Castillo. 2011. Efecto del uso del suelo en las hormigas (Formicidae: Hymenoptera) de Tikinmul, Campeche, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana. Vol. 27, Núm. 2. pp: 441-461. [ Links ]

Cortes-Pérez, Francisco, León-Sicard, y Tomás Enrique. 2003. Modelo conceptual del papel ecológico de la hormiga arriera (Atta leavigata) en los ecosistemas de sabana estacional (Vichada, Colombia). Caldasia. Vol. 25, Núm 2. pp: 403-417. [ Links ]

Costa-Neto, Eraldo M. 2002. Manual de etnoentomología. Zaragoza, España. Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa. 256 p. [ Links ]

Costa-Neto, Eraldo M., y Julieta Ramos-Elorduy. 2006. Los insectos comestibles de Brasil: etnicidad, diversidad e importancia en la alimentación. Bol. de la Soc. Ent. Aragonesa. Vol. 38, pp: 423-442. [ Links ]

Cuadrillero Aguilar, José Ignacio. 1980. Consideraciones biológicas y económicas acerca de los Escamoles. Tesis Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, Ciudad de México. [ Links ]

Cruz-Labana, José Domingo, Luis Antonio Tarango-Arámbula, José Luis Alcantara-Carbajales, José Pimentel-López, Saúl Ugalde-Lezama, Gustavo Ramirez-Valverde, y S. J. Méndez-Gallegos. 2014. Uso del hábitat por la hormiga escamolera (Liometopum apiculatum Mayr) en el Centro de México. Agrociencia. Vol. 48, Núm. 6. pp: 569-582. [ Links ]

Curts, Jaime. 1993. Análisis exploratorio de datos. In: P. M. A. Salas, y C. O. Trejo. 1993. Las aves de la Sierra Purépecha del Estado de Michoacán. Coyoacán, México, SARH División Forestal, p. 14 (Boletín Informativo #79). [ Links ]

Di Rienzo J. A., F. Casanoves, M. G. Balzarini, L. Gonzalez, M. Tablada, y C. W. Robledo. 2013. InfoStat versión 2013. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. URL http://www.infostat.com.ar [ Links ]

Dinwiddie, M. L., R. W. Jones, P. Roitman-Genoud, L. A. Tarango-Arámbula, y G. X. Malda-Barrera. 2013. Estudio entoentomológico de la hormiga escamolera (Liometopum apiculatum) en dos localidades en el estado de Querétaro. Agroproductividad. Vol. 6, Núm. 5. pp: 27-34. [ Links ]

Dufour, Darma. 1987. Insects as food. A case study from the northwest Amazon. Amer. Anthropol. Vol. 89, Num. 2. pp: 383-397. [ Links ]

Engel, Michael S., and David A. Grimaldi. 2004. New light shed on the oldest insect. Nature. Vol. 427, Num. 6975. pp: 627-630. [ Links ]

Esparza-Frausto, Gastón, Francisco J. Macías-Rodríguez, Martín Martínez-Salvador, Marco A. Jiménez-Guevara, y Santiago de J. Méndez-Gallegos. 2008. Insectos comestibles asociados a las Magueyeras en el Ejido, Tolosa, Pinos, Zacatecas, México. Agrociencia . Vol. 42, Núm. 2. pp: 243-252. [ Links ]

ESRI. 2012. ArcGis 10.1. [ Links ]

Fisher, Ronald Aylmer. 1993. Statistical methods experimental design and scientific inference. New York, U.S.A. Oxford Science Publications. New Science Publications. 182 p. [ Links ]

García, Enriqueta. 1998. Climas, escala 1:1 000 000. CONABIO. [ Links ]

Gómez, Crisanto, y Xavier Espadaler. 1996. Distancias de forrajeo, áreas de forrajeo y distribución espacial de nidos de Aphaenogaster senilis Mayr (Hym:Formicidae). Miscelánia Zoológica. Vol. 19, Núm. 2. pp: 19-25. [ Links ]

González-Espinosa, Mario. 1984. Patrones de comportamiento de forrajeo de hormigas recolectoras Pogonomyrmex spp. en ambientes fluctuantes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Folia Entomológica Mexicana, Vol. 61, Núm. pp: 147-158. [ Links ]

Hoey-Chamberlain, Rochelle, Michael K. Rust, and John H. Klotz. 2013. A review of the biology, ecology and behavior of velvety tree ants of North America. Sociobiology. Vol. 60, Núm. 1. pp: 1-10. [ Links ]

Jenks, Keith E., Prawatsart Chanteap, Kanda Damrongchainarog, Peter Cutter, Passanan Cutter, Tim Redford, Antony J. Lynam, JoGayle Howard, and Peter Leingruber. 2011. Using relative abundance indices from camera-trapping to test wildlife conservation hypotheses -an example from Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. Tropical Conservation Science, Vol. 4, Num. 2. pp: 113-131. [ Links ]

Jofré, Laura, y Ana I. Medina. 2012. Patrones de actividad forrajera y tamaño de nido de Acromyrmex lobicornis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) en una zona urbana de San Luis, Argentina. Rev. Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. Vol. 71, Núm. 1-2. pp: 37-44. [ Links ]

Juárez-Sandoval, José de Jesús, Virginia Eustolia Melo-Ruiz, Demetrio Pérez-Santiago, y Concepción Calvo-Carrillo. 2010. Contenido de proteínas y aminoácidos en Escamoles (Liometopum apiculatum M.) capturados en el estado de Hidalgo. Congreso Internacional QFB No.10. San Nicolás de los Garza, México. In: Revista Salud Pública y Nutrición Edición Especial No. 10. [ Links ]

Kusnezov, N. 1975. Numbers of species of ants in faune of differents latitudes. Evolution. Vol. 11, Num. 3. pp: 298-299. [ Links ]

Lara-Juárez, P., J. R. Aguirre Rivera, P. Castillo Lara, y J. A. Reyes Agüero. 2015. Biología y aprovechamiento de la hormiga de escamoles, Liometopum apiculatum Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Acta zoológica mexicana. Vol. 31, Núm. 2. pp: 251-264. [ Links ]

Lokeshwari, R. K., and T. Shantibala. 2010. A Review on the Fascinating World of Insect Resources: Reason for Thoughts. Psyche. Vol. 32, Num. 4. pp: 1-11. [ Links ]

Martella, Mónica B., Eduardo Trumper, Laura M. Bellis, Daniel Renison, Paola F. Giordano, Gisela Bazzano, y Raquel M. Gleiser. 2012. Manual de Ecología. Poblaciones: Introducción a las técnicas para el estudio de las poblaciones silvestres. Reduca (Ecología). Serie Ecología. Vol. 5, Núm. 1. pp: 1-31. [ Links ]

Martínez, Carmen Lidia, Maríz Begoña Riquelme-Virgala, Marina Vilma Santadino, Ana María de Haro, y Jutos José Barañao. 2015. Estudios sobre el comportamiento de Forrajeo de Acromyrmex lundi Guering (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) y su efecto sobre el crecimiento de procedencia de Eucalyptus globulus Labill (Mytaceae). Árvore. Vol. 39, Núm. 1. pp: 189-198. [ Links ]

Microsoft Office. 2013. Microsoft Excel 2013. [ Links ]

Miranda, A. Bruno, Kazuya Naoki, y Miguel Limanchi. 2012. Ensamble de hormigas en relación a cobertura vegetal en una zona periurbana de La Paz (Bolivia). Ecología en Bolivia. Vol. 47, Núm. 2. pp: 119-133. [ Links ]

Molinero, Luis Miguel. 2003. ¿Y si los datos no se ajustan a una distribución normal? Bondad de ajuste a una normal. Transformaciones. Pruebas no paramétricas. Asociación de la Sociedad Española de Hipertensión. Liga Española para la lucha contra la Hipertensión Arterial. Madrid, España. [ Links ]

Novoa, Sidney, Inés Redolfi, Aldo Ceroni, y Consuelo Arellano. 2005. El forrajeo de la hormiga Camponotus sp. en los botones florales del cactus Neoraimondia arequipensis subsp. roseiflora (Wendermann and Backenberg) Ostolaza (Cactaceae). Ecología aplicada, Vol. 4, Núm. 1,2. pp: 83-90. [ Links ]

Pirk, Gabriela I., Javier López De Casenave, y Rodrigo G. Pol. 2004. Asociación de hormigas granívoras Pogonomyrmex pronotalis, P. rastratus y P. inermis con caminos en el Monte central. Asociación Argentina de Ecología. Ecología Austral, Vol. 14, Núm. 1. pp: 65-76. [ Links ]

R: Copyright 2014. The R foundation for statistical computing Version 3.1.1 [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, J., Bernadette Délgade-Darchen, J. I. Cuadrillero Aguilar, N. Galindo Miranda, y José Manuel Pino Moreno. 1984. Ciclo de vida y fundación de las sociedades de Liometopum apiculatum M. (Himenoptera-Formicidae). Anales del Instituto de Biología UNAM serie Zoología. Vol. 55. pp: 161-176 [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta, Bernadette Darchen, Alberto Flores-Robles, Eusebia Sandoval-Castro, Socorro Cuevas-Correa. 1986. Estructura del nido de Liometopum occidentale var. luctuosum manejo y cuidado de estos en los nucleos rurales de México de las especies productoras de escamol (L. apiculatum M y L. occidentale var. luctuosum W.) (Hymenoptera-Formicidae). Anales Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Vol. 57, Serie Zoológica, Núm. 2. pp: 333-342. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta , Bernadette Délgade-Darchen y N. E. Galindo. 1988. Observaciones biotecnológicas de Liometopum apiculatum M. y Liometopum occidentale Var. Luctuosum W. (Himenoptera-Formicidae). Anales del Instituto de Biología UNAM serie Zoología. Vol. 59. pp: 341-354. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta . 1991. Los insectos como fuente de proteínas del futuro. Distrito Federal, México. Edit. Limusa S. A. primera reimpresión. p. 92. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta . 2005. Insectos comestibles de México. Distrito Federal, México. McGraw-Hill. 110 p. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta ; José Manuel Pino Moreno , ySocorro Cuevas-Correa . 1998. Insectos comestibles de México y determinación de su valor nutritivo. Anales Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México , Ser. Zoológica. Vol. 69. pp: 65-104. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta , yJosé Manuel Pino Moreno . 2005. El consumo de insectos; una alternativa alimenticia sana y nutritiva. Día V. pp: 46-49. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta , José Manuel Pino Moreno , y Mariangela Conconi. 2006. Ausencia de una regulación y normalización de la explotación y comercialización de insectos comestibles en México. Folia Entomológica Mexicana . Vol. 45, Núm. 3. pp: 291-318. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta . 2008. Energy supplied by edible insects from Mexico and their nutritional and ecological importance. Ecology of food and nutrition. Vol. 47, Núm. 3. pp: 280-297. [ Links ]

Ramos-Elorduy, Julieta , José Pino Moreno , y V. H. Martínez. 2008. Una visita a la biodiversidad de la antropoentomofagia mundial. In: E. G. Estrada-Venegas, A. Equihua-Martínez, J. R. Padilla-Ramírez, y A. Mendoza-Estrada (eds). 2008. Entomología Mexicana. Sociedad Mexicana de Entomología y Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México, México. Vol. 7. 1092 p. [ Links ]

Rzedowsky, J. 1978. Vegetación de México: Ciudad de México. México: Limusa Wiley. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J., y L. Huerta. 1994. vegetación de México (No. QK211. R93 1978.). México: Limusa, Noriega Editores. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Cancino, Enrique, Dimitri R. Kasparyan, Juana María Coronado-Blanco, Svetlana N. Myartseva, Vladimir A. Trjapitzin, Sonia G. Hernández-Aguila, y Jesús García-Jímenez. 2010. Hymenopteros de la Reserva El Cielo, Tamaulipas, México. Universidad de Guadalajara. Dugesiana. Vol. 17, Núm. 1. pp: 53-71. [ Links ]

Rojas-Fernández, P. 2001. Las hormigas del suelo en México: Diversidad, distribución e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie). Es. 1. pp: 189-238. [ Links ]

Stradling, D. J. 1978. Food and feeding hábitats of ants. International Biological Programme. [ Links ]

Tarango-Arámbula, Luis Antonio. 2012. Los escamoles y su producción en el Altiplano Potosino-Zacatecano. X Simposium-Taller Nacional y III Internacional Producción y Aprovechamiento del Nopal y Maguey. RESPYN: Revista Salud Pública y Nutrición , Edición Especial, Vol.4. pp: 139-144. [ Links ]

Tizon, Francisco Rodrigo, Daniel V. Peláez, y Omar E. Elía. 2010. Efecto cortafuegos sobre el ensamblaje de hormigas (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en una región semiárida, Argentina. Iheringia, Ser. Zoológica, Porto Alegre. Vol. 100, Núm. 3. pp: 216-221. [ Links ]

Velasco-Corona, Cecilia, María del Carmen Corona-Vargas, y Rebeca Peña-Martínez. 2007. Liometopum apiculatum (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) y su relación trofobiótica con Heminoptera esternorrhyncha en Tlaxco, Tlaxcala, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (Nueva serie). Vol. 23, Núm. 2. pp: 31-42. [ Links ]

Villegas, D., A. Daza, B. Kohlmann, y J. Tejada. 2005. Estudio de prefactibilidad para la reproducción y comercialización de escarabajos del género Phaenaeus MacLeay. Tierra Tropical. Vol. 1, Núm, 1. pp: 61-67. [ Links ]

Received: March 01, 2016; Accepted: January 01, 2018

text in

text in