Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.14 n.4 Texcoco Oct./Dec. 2017

Articles

Dominance, chemical-nutritional composition, and potential phytomass of fodder species in a secondary rainforest

1 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Ciudad Universitaria. México. (anyagof@yahoo.com.mx) (grebeles@unam.mx).

2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Veracruz. México. (silvialopez@colpos.mx).

3 Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias. México. (kvera@uady.mx) (c.albor@hotmail.com).

4 Tecnológico de Conkal. Avenida Tecnológico s/n Conkal, Yucatán. México. (roberto.sangines@itconkal.edu.mx).

The relationship between abundance, dominance and similarity of fodder species with the nutritional quality and quantity of potential phytomass for feeding bovines was determined, in sites with forest, shrub and herbaceous vegetation in dry and rain season. Fifty-four (54) fodder species were found grouped into 21 families (with Fabacea dominating). The abundance of woody fodder was higher in the rain season in the forest community (p<0.0001; 52.8±11.4) and in the dry season in the shrub community (p=0.002; 14.80±3.09). The similarity between communities varied from 0.27 to 0.54. The dominating fodder species of the forest community in the rain season presented high nutritional values, ruminal degradability (65.9-89.0 %) and metabolizable energy (9.35-11.52 MJ/kg DM). The highest content of tannins was in Bauhinia divaricata (12.75 %). The potential phytomass yielded 3272 and 1454 kg DM/ha in the rain and dry seasons, respectively, and was higher in herbs (P<0.0001; 3977±2299 and 2451±3336, respectively). A large diversity of fodder species was found, different in each plant community, and which differ in chemical-nutritional quality. As a whole, the potential phytomass of all the strata and the variety of nutrients that the species contain complement each other to feed bovines throughout the year.

Key words: nutrients; diversity; native vegetation; bovines

Se determinó la relación entre abundancia, dominancia y similitud de especies forrajeras con la calidad nutritiva y cantidad de fitomasa potencial para la alimentación de bovinos en sitios con vegetación forestal, arbustiva y herbácea en la época seca y la lluvia. Se encontraron 54 especies forrajeras agrupadas en 21 familias (dominando Fabacea). La abundancia de leñosas forrajeras fue mayor en temporada de lluvias en la comunidad forestal (p<0.0001; 52.8±11.4) y en la de secas en la arbustiva (p=0.002; 14.80±3.09). La similitud entre comunidades varió de 0.27 a 0.54. Las especies forrajeras dominantes de la comunidad forestal en lluvias presentaron altos valores nutricionales, degradabilidad ruminal (65.9-89.0 %) y energía metabolizable (9.35-11.52 MJ/kg MS). El mayor contenido de taninos fue en Bauhinia divaricata (12.75 %). La fitomasa potencial rindió 3272 y 1454 kg MS/ha en lluvias y secas, respectivamente, y fue mayor en herbáceas (P<0.0001; 3977±2299 y 2451±3336, respectivamente). Se encontró una gran diversidad de especies forrajeras, diferentes en cada comunidad vegetal, y que difieren en calidad químico-nutritiva. En su conjunto, la fitomasa potencial de todos los estratos y la variedad de nutrientes que las especies contienen se complementan para alimentar bovinos a lo largo del año.

Palabras clave: nutrientes; diversidad; vegetación nativa; bovinos

Introduction

Extensive livestock production is practiced approximately in 30 % of the rainforests or tropical forests of the world (FAO, 2009) and is associated with the change in land use (FAO, 2013). The husbandry practices related to the change in land use cause deforestation, decrease in biodiversity and in environmental services, and alter the biogeochemical cycles, contributing to global climate change (LEAD, 2006). Facing this problematic, livestock reconversion is imperative toward environment-friendly production systems where monocrops of improved varieties of grasses are replaced by grasses with lower water requirements and perennial plant species, as well as the grazing practices in secondary vegetation (Ferguson et al., 2013; Nahed et al., 2013).

Traditionally, the extensive livestock production systems are based on grass monocrops to provide biomass and nutrients to the cattle (Ayala et al., 2006), without taking into account that in order to establish monocrops the native vegetation with fodder potential is displaced (Flores and Bautista, 2012). It has been documented that these species can contain raw protein above 12 % of the dry matter (DM), wide ranges of neutral detergent fiber and acceptable ruminal degradability (Flores and Bautista, 2012; Rojas et al., 2016). The presence of secondary metabolites, which have important biological applications in animal nutrition and health, is associated to their chemical-nutritional quality; such is the case of condensed tannins which are capable of decreasing the load of intestinal parasites and the emissions of enteric methane from ruminants (Mueller, 2006; Gerber et al., 2013). However, the animal load capacity of these sites where the tree vegetation associated to grasses is kept is still a mystery to be solved, so it is possible to distribute the management of fodder biomass throughout the year. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the fodder available from natural vegetation in the Yucatán Peninsula can vary from 821 to 2 463 DM/ha/year, with a variable animal load capacity between 0.16 and 0.50 UA/ha/year, variation associated to the type of vegetation and soil (CICC, 2009; Escamilla et al., 2005). Little is understood about its productivity, the relationships between potential fodder for livestock and the changes in abundance of native species through different successional stages of the medium sub-deciduous rainforest, so diagnoses are required that allow understanding these relationships in order to achieve the optimization of the exploitation and management of available biomass with fodder use directed toward the conservation of plant communities. Because of this, the objective of this study was to determine the relationship between abundance and similarity of plants with fodder potential, both woody and herbaceous, in the secondary vegetation, with the nutritional quality and quantity of potential fodder for bovine livestock. The hypothesis set out is that with higher abundance of plants with fodder potential in the secondary vegetation there will be higher complementation of nutrients and higher potential phytomass for the cattle.

Materials and Méthods

Location and description of the study area

The research was carried out during 2013 and 2014 in the municipality of Tzucacab, Yucatán, México, between coordinates 19° 55’ 823’’ and 20° 00’ 873’’ N and 88° 57’ 818’’ and 89° 02’ 580’’ W, with 165 m of average altitude. The soil is of karstic origin, characterized by the presence of Leptosol, Cambisol and Luvisol (Flores and Bautista, 2005). The climate is sub-humid warm (Aw0) (García and CONABIO, 1998). The mean annual temperature during 2015 was 27.5 °C and the accumulated annual precipitation, 1 210 mm (CONAGUA, 2015). The type of vegetation is secondary medium sub-deciduous rainforest (Flores and Espejel, 1994; Zamora et al., 2009). Three bovine production units (BPUs) were evaluated within a radius of 15 km. The BPUs were made up of double-purpose animals (Box Taurus x Bos indicus), in their majority cows (75-85 %). The size of the pastures ranged between 10 and 40 ha, with a resting period from grazing of between one and three months. The cattle diet was based on the consumption of grasses and secondary vegetation throughout the year. The surface and animal load of the BPUs were 130 and 0.33, 108 and 0.19, and 800 and 0.10 hectares and UA/ha/year, respectively, considering UA equivalent to one bovine of 450 kg live weight.

Based on the description of the plant succession by Flores (2001), the forest, shrub and herb communities are distinguished. The Forest Community (FC) was characterized by the presence of trees with more than 8 m of height, diameter at breast height (DBH) higher or equal to 10 cm and 10 to 15 years of abandonment. In the Shrub Community (SC) trees below 4 m of height were found, DBH lower than 10 cm, with shrub dominance and two to ten years of abandonment; and in the Herb Community (HC), with presence of herbs, grasses, vines or lianas and two to four years of abandonment. One of the BPUs did not have HC and another one lost it during the dry season.

Description of the study

The vegetation of a medium sub-deciduous rainforest in different successional stages was characterized to understand the level of dominance of the fodder species, through the index of relative value of importance (RVI). The differences in abundance of fodder species between plant communities were analyzed. The dry matter content of the potential phytomass was estimated in the woody and herbaceous strata of the FC, SC and HC during the rainy season (October and November 2013) and dry season (April and May 2014). The chemical-nutritional contents, in situ ruminal degradability of the dry matter, and the concentration of metabolizable energy of the fodder species collected were determined at 48 h during the rainy season in the study area.

Sampling of the vegetation

A first group of variables made up of the wealth, abundance, frequency, DBH and coverage of all the plants found was evaluated, with the aim of estimating the RVI and understanding the level of dominance of the fodder species. For this purpose, in each type of plant community 75 m to the west were visited systematically (Bautista et al., 2004). At the end of the visit the establishment of sampling frames began, with a distance of 10 meters between each. Four sampling frames of 16 m2 (4´4 m) were placed for the woody stratum, with nested frames of 1 m2 for the herbaceous stratum (Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg, 1974; Bonham, 1989). In the FC and SC, 24 nested frames were placed in total per community and in the HC only 12 were placed, due to the absence of the woody stratum and because there wasn’t always a HC in the BPUs.

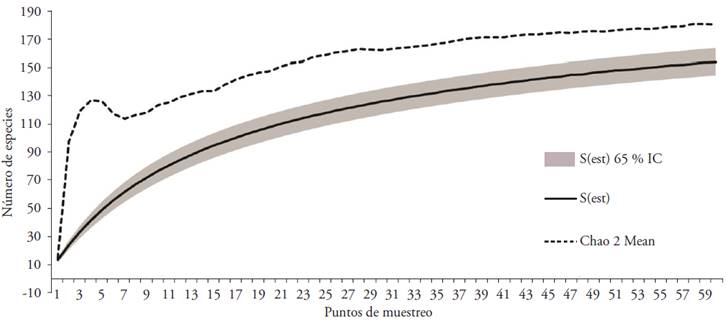

The representativeness of the sample was calculated through an accumulation curve of species using the Chao 2 Mean model (Estimate S version 9.1.0, Colwell 2013), which is more adequate when there are data of presence-absence of the species (Álvarez et al., 2006). The species were identified in the “Alfredo Barrera Marín” herbarium of the School of Veterinarian Medicine and Animal Husbandry of the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, FMVZ-UADY).

Potential phytomass

A second group of variables made up of the potential phytomass of the secondary vegetation and ruminal degradability was evaluated, and the concentration of metabolizable energy of fodder species. The potential phytomass was collected in the sampling frames of 1 m2 previously established, with the objective of describing in detail the fodder potential of the plant community strata. The potential phytomass which was in reach of the animals was considered (Bello et al., 2001). For their sampling, fodder, fruits, flowers and tender stems were defoliated manually within the 1 m2 frames previously established and at a height of between 5 and 170 cm. The material collected was dried at 60 °C in a forced air stove during 72 h (AOAC, 2000).

Nutritional analysis

The purpose of analyzing the chemical-nutritional composition and determining the ruminal degradability and concentration of metabolizable energy was to describe the nutritional characteristics of the fodder species found in the medium sub-deciduous rainforest consumed by bovines. All the plants present in the stratum of 5 to 170 cm height were included, which in previous works had been identified as fodder species (Sosa et al., 2000; Ayala et al., 2006; Alonso et al., 2009; Velázquez et al., 2010; Flores and Bautista, 2012). The collection was carried out in November 2013, considering that the dominant vegetation would be flowering (Flores, 2001), thus reflecting optimal levels of nutrients for the livestock (Ayala et al., 2006). Manually, 1 kg of leaves, fruits and tender stems of the species listed as fodder and present in the sampling sites was cut.

Chemical-nutritional composition of fodder species

The neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was determined through filtered bags, applying method 6 from Ankom Technology (Ankom Tecnology A200 and A200I) (Van Soest et al., 1991), raw protein (RP N × 6.25) with an elemental analyzer (C, N), Lecco CN-2000 series 3740 (Lecco, 2013) and condensed tannins (CT), using the colorimetric method of Vanillin-Hydrochloric Acid (Makkar and Becker, 1993) on 20 dominating fodder species, identified as such after calculating the RVI. The results from the CT should be approached carefully, since no liquid nitrogen was used during the sampling nor was it refrigerated later for the preservation of the samples.

Determination of ruminal degradability and concentration of metabolizable energy

After 48 hours, assays of ruminal degradability were performed in situ of the dry matter on 16 of the most dominating fodder species. The technique of nylon bag with a pore opening of 53 µm (Ørskov et al., 1980) was used in two cows (430 kg of live weight) canulated in the rumen and fed with 20 kg of Pennisetum purpureum (cv Taiwan), 4 kg of Leucaena leucocephala and 1 kg of concentrate (13.5 % of PC). The metabolizable energy (ME) was estimated, using the in situ degradability of dry matter (DisDM) with the following equation (Orskov et al., 1980):

Data analysis

In order to describe the levels of dominance, the RVI of the herbaceous and woody strata of all the species (fodder and non-fodder) was estimated (Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg, 1974). The values of abundance, frequency, coverage and DBH found in the production units were integrated into a single group of data for the FC, another for the SC and a last one for the HC. The fodder species with highest dominance were selected to subject them to chemical-nutritional analysis.

Statistical analysis

To determine whether the composition of fodder species changed between the different vegetation communities studied, their similarity was estimated through the Sorensen Coefficient (Magurran, 1988) using the method of paired group analysis without bias, with the arithmetic mean (UPGMA), using the Statistical Multivatiate Program (MVSP, version 3.1, 1985-2013, Kovach Computing Services) (Sørensen, 1948; Kovach, 2007). The variable of absolute abundance was selected as an indicator of proportion (Magurran, 1988) of fodder species inside each plant community. Variance analyses were performed of the absolute abundance of fodder species and the potential phytomass, applying factorial models of 2×2 (two plant communities for two times of the year in woody) and 3×2 (three plant communities for two times of the year in herbaceous). The SAS software was used (Statistical Analysis System Inc. 2000; North Caroline; USA; version 8.1.).

Results and Discussion

Attributes of the vegetation and of the fodder species

More than one thousand individuals (1745) were found, distributed in 154 species, grouped into 49 families (fodder and non-fodder). According to the Chao 2 Mean estimator, the accumulation curve of species did not reach the asymptote (Figure 1); however, a representation of 85.5 % of the wealth expected (180 species) was obtained.

I.C.: interval of trust, S (est): species observed.

Figure 1 Accumulation curve of Chao 2 Mean species.

The wealth of fodder species was 54, grouped into 21 families, in contrast with the eight fodder species found in the municipality of Tzucacab, Yucatán (Zamora et al., 2009) and 35 fodder species for bovines in the Yucatán Peninsula (Flores and Bautista, 2012), indicating a high wealth of fodder species in the sites studied. The fodder wealth was numerically higher in the rainy season, except in the SC (Table 1), suggesting the presence of species with highest resistance to drought in this type of community. The Fabaceae family was the most represented (Table 2) and the most dominant (Table 3), in agreement with Flores and Bautista (2012), Zamora et al. (2008) and Gutiérrez et al. (2012). This is explained because it is one of the most important families in the world flora and in the tropics (Flores, 2001), which is why it has been considered an important fodder in animal production (NAS, 1979).

Table 1 Wealth of fodder species per plant community, stratum and season of the year in a medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest.

| Estrato vegetal | Comunidad forestal | Comundad arbustiva | Comunidad herbácea | |||

| Lluvias | Secas | Lluvias | Secas | Lluvias | Secas | |

| Estrato leñoso | 21 | 16 | 16 | 16 | − | − |

| Estrato herbáceo | 8 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 6 |

Table 2 Species considered as fodder in bovine grazing sites in a medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest.

| Familia | Número de especies | Especie | Fuente bibliográfica |

| Amaranthaceae | 1 | Celosia virgata Jaq. | CICY, 2010 |

| Arecaceae | 2 | Acrocomia aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. | Andrade et al., 2008 |

| Sabal yapa C. Wright Becc. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 | ||

| Asteraceae | 2 | Melanthera angustifolia A. Rich. | CICY, 2010 |

| Viguiera dentata (Cav.) Spreng. var. dentata | González et al., 2014 | ||

| Boraginaceae | 2 | Cordia globosa (Jacq.) Kunth | Romero y Duarte, 2012 |

| Ehretia tinifolia L. | Ayala et al., 2006 | ||

| Burseraceae | 1 | Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 |

| Convolvulaceae | 1 | Merremia aegyptia (L.) Urb. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 |

| Cyperaceae Juss. | 2 | Cyperus haspan L. | CICY, 2010 |

| Cyperus odoratus L. | CICY, 2010 | ||

| Euphorbiaceae | 1 | Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (Mill.) I.M. Johnst. | González et al., 2014 |

| Fabaceae | 20 | Acacia collinsii Saff. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 |

| Acacia cornigera (L.) Willd. | Vásquez et al., 2012 | ||

| Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. | Ayala et al., 2006 | ||

| Acacia pennatual (Schltdl. & Cham.) Benth. | Ayala et al., 2006, Flores y Bautista, 2012 | ||

| Bauhinia divaricata L. | Jackson, 1996 | ||

| Bauhinia ungulata L. | Pinto et al., 2004 | ||

| Chloroleucon mangense (Jacq.) Britton & Rose | CICY. 2010 | ||

| Dalbergia glabra (Mill.) Standl. | Sosa et al., 2000 | ||

| Desmodium incanum DC. | Sosa et al., 2000, Jackson, 1996 | ||

| Desmodium tortuosum (Sw.) DC. | Sosa et al., 2000 | ||

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum Griseb. | Rico et al., 1991 | ||

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit. ssp. Leucocephala | Flores y Bautista, 2012 | ||

| Lonchocarpus punctatus Kunth. | Achan et al., 2011 | ||

| Lonchocarpus rugosus Benth. | Cab et al., 2015 | ||

| Mimosa pudica L. | ECOCROP, 2007 | ||

| Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. | Adjorlolo et al., 2004 | ||

| Piscidia piscipula (L.) Sarg. | Ayala et al., 2006, Flores y Bautista 2012 | ||

| Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 | ||

| Senna uniflora (Mill.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby. | Jackson, 1996 | ||

| Lamiaceae | 3 | Callicarpa acuminata Kunth. | Mizrahi et al., 1997 |

| Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 | ||

| Vitex gaumeri Greenm. | Ayala et al., 2006, Flores y Bautista 2012 | ||

| Malpighiaceae | 1 | Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth. | Rico et al., 1991 |

| Malvaceae Juss. | 3 | Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | Flores y Bautista 2012 |

| Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. | Velázquez et al., 2010 | ||

| Sida acuta Burm. F. | Vásquez et al., 2012 | ||

| Marantaceae | 1 | Maranta arundinacea f. sylvestris Matuda. | ECOCROP 2007 |

| Nyctaginaceae | 1 | Pisonia aculeata L. | Velázquez et al., 2011 |

| Picramniaceae | 1 | Alvaradoa amorphoides Liebm. ssp. Amorphoides | Sosa et al., 2000 |

| Poaceae | 6 | Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. | Sadi et al., 2015 |

| Lasiacis ruscifolia (Kunth) Hitchc. var. ruscifolia | CICY, 2010 | ||

| Oplismenus burmannii (Retz.) P. Beauv. | CICY, 2010 | ||

| Panicum maximum Jacq. | Castellón y Elías, 2015 | ||

| Paspalum plicatulum Michaux | Vásquez et al., 2012 | ||

| Paspalum langei ( E. Fourn) Nash | CICY, 2010 | ||

| Rubiaceae | 3 | Guettarda combsii Urb. | Sosa et al., 2000 |

| Hamelia patens Jacq. | Sosa et al., 2000 | ||

| Psychotria nervosa Sw. | López et al., 2008 | ||

| Sapotaceae | 1 | Chrysophyllum mexicanum Brandegee in Standl. | Sosa et al., 2000 |

| Solanaceae | 1 | Solanum hirtum Vahl. | Flores y Bautista, 2012 |

| Violaceae | 1 | Hybanthus yucatanensis Millsp. | Mizrahi et al., 1997 |

Table 3 Values of relative importance of the fodder species in the different plant communities in the medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest in the rain and dry seasons.

| Comunidad forestal | Familia | Época de lluvias de 2013 | Familia | Época de secas de 2014 | |||||

| Especie | Nivel VIR | Especie | VIR% | Nivel VIR | VIR % | ||||

| Estrato leñoso. | Arecaceae | Sabal yapa | 1 | 39.45 | Solanaceae | Solanum hirtum | 1 | 36.61 | |

| Fabaceae | Bauhinia divaricata | 2 | 38.34 | Violaceae | Hybanthus yucatanensis | 2 | 24.03 | ||

| Entre 1 y 4 m de alto promedio | Violaceae | Hybanthus yucatanensis | 3 | 34.29 | Malvaceae | Guazuma ulmifolia | 5 | 19.15 | |

| Fabaceae | Piscidia piscipula | 4 | 29.56 | Fabaceae | Piscidia piscipula | 6 | 17.15 | ||

| Estrato herbáceo | Poaceae | Lasciasis ruscifolia | 1 | 44.87 | Amaranthaceae | Celosia virgata | 2 | 18.6 | |

| Amaranthaceae | Celosia virgata | 2 | 45.18 | Poaceae | Lasiacis divaricata | 7 | 14.44 | ||

| Fabaceae | Mucuna pruriens | 7 | 18.47 | Fabaceae | Dalbergia glabra | 8 | 13.39 | ||

| Marantaceae | Maranta arundinicea | 11 | 9.79 | Malvaceae | Sida acuta | 15 | 7.97 | ||

| Estratovegetal leñoso | Fabaceae | Bauhinia ungulata | 1 | 111.76 | Fabaceae | Bauhinia ungulata | 1 | 26.5 | |

| Entre 0.5 y 2 m de alto promedio | Fabaceae | Acacia pennatula | 2 | 34.57 | Arecaceae | Sabal yapa | 2 | 24.65 | |

| Fabaceae | Senna uniflora | 3 | 24.94 | Fabaceae | Acacia collinsii | 3 | 22.27 | ||

| Fabaceae | Piscidia piscipula | 4 | 21.62 | Fabaceae | Acacia pennatula | 4 | 20.43 | ||

| Estrato vegetal herbáceo | Lamiaceae | Hyptis suaveolens | 1 | 46.87 | Poaceae | Ischaemum rugosum | 1 | 54.12 | |

| Poaceae | Ischaemum rugosum | 2 | 45.5 | Poaceae | Panicum maximum | 5 | 19.73 | ||

| Poaceae | Lasciasis ruscifolia | 12 | 7.29 | Fabaceae | Desmodium incanum | 6 | 19.56 | ||

| Poaceae | Paspalum langei | 15 | 5.22 | Malvaceae | Sida acuta | 14 | 5.2 | ||

| Comunidad herbácea | Malvaceae | Sida acuta | 3 | 19.68 | Poaceae | Panicummaximum | 2 | 24.03 | |

| Fabaceae | Mucuna pruriens | 4 | 16.97 | Asteraceae | Melanthera angustifolia | 4 | 13.93 | ||

| Marantaceae | Maranta arundinacea | 5 | 13.22 | Fabaceae | Desmodium incanum | 13 | 8.26 | ||

RVI: Index of value of relative importance in a scale of 1 to 300.

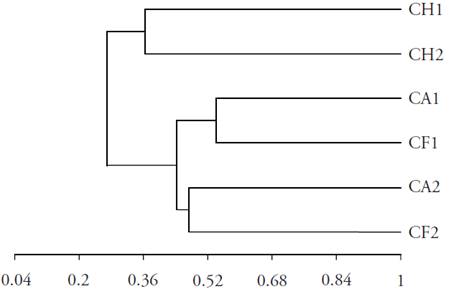

In terms of the type of fodder species and their dominance in relation to the type of vegetation or time of abandonment (Table 3), similar species to those found by Flores (2001) were observed in the henequen zone of Yucatán, with ranges of RVI relatively similar in Hyptis suaveloens (RVI 10.19 %), Piscidia piscipula (RVI 79.74 %) and Guazuma ulmifolia (RVI 25.02 %) in sites with two, five and fifteen years of abandonment, respectively. The woody fodder species had the tendency of occupying the first places of relative importance (RVI) and the herbaceous fodders lower places, except in the Herbaceous Community, where the herbaceous fodder species in the medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest dominated (Table 3). The dominance of perennial fodder species could favor the permanence of potential food in the critical time of the year, especially species such as Acacia pennatula, Celosia virgata, Guazuma ulmifolia, Hybanthus yucatanensis and Piscidia piscipula (CICY, 2010), while in the HC the Poaceas dominated primarily, because it is a young stage of succession with low tolerance to shade and resistant to grazing (Gleen-Lewin et al., 1992; Villegas et al., 2001). On the other hand, the similarity between the Forest and Shrub communities was 0.54 in rain season and 0.47 in dry season; in the Herb Community in rain and dry seasons it was 0.36, and in Herb Community with the Forest and Shrub communities it was 0.27 (Figure 2), which indicated that the type of species changed between plant communities, offering a great variety of species.

CH1: Herbaceous community in rain season; CH2: Herbaceous community in dry season. CA1: Shrub community in rain season; CA2: Shrub community in dry season. CF1: Forest community in rain season; CF2: Forest community in dry season.

Figure 2 Dendrogram of similarity from the Sorensen Coefficient of the species considered as fodder in the sub-deciduous medium rainforest.

On the other hand, interaction was found from the effect of season and community in the abundance of woody fodder species (p=0.01), with it being higher in the rain season of the Forest Community (p<0.0001) and in the dry season in the Shrub Community (p=0.0019) (Table 4). In terms of the abundance in the Forest Community, it was favored in woody species in the rain season and the Shrub Community was less affected in the dry season, making the SC a food reservoir in the critical drought season. The high variance in the abundance of herb species in the FC was explained by the low tolerance of this stratum to the shade (Gleen-Lewin et al., 1992), which is why different light conditions created by the woody stratum can vary within the same site, originating constant differences in their abundance. In this sense it is necessary to understand the selectivity and preferences of the livestock when selecting their diet to understand how the nutritional wealth of the secondary vegetation is exploited.

Table 4 Absolute abundance of fodder species in function of the plant community and season of the year in the medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest.

| Comunidad vegetal | Comunidad forestal | Comunidad arbórea | Comunidad herbácea | Efecto época (p) | Efecto comunidad (p) | Efecto interacción (p) | |||

| Lluvias | Secas | Lluvias | Secas | Lluvias | Secas | ||||

| Estrato leñoso | |||||||||

| Abundancia absoluta | 52.8a±11.4 | 14.80d±3.09 | 29.8b±11.81 | 16.8c±2.87 | - | - | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Estrato herbáceo | |||||||||

| Abundancia absoluta | 12.0b±12.59 | 4.5c±9.0 | 40a±19.50 | 20.0b±10.70 | 36a±6.70 | 13b±7.63 | 0.0008 | 0.001 | 0.30 |

p: value of significance; ±: standard deviation. In the values that don’t share literal, significant difference was found (p≤0.05).

Potential phytomass

The potential phytomass of the secondary vegetation was 3272 kg DM/ha in the rainy season and 1454 kg DM/ha in the dry season throughout all the strata and communities, which agrees with the amounts of fodder available reported by CICC (2009) for the Yucatán Peninsula, with the animal load used in the study sites being consistent with the capacity of animal load indicated for the region (CICC, 2009). In the woody fodder stratum there was higher potential phytomass in the Forest Community in the rain season (2030±741 kg DM/ha) explained by the impact of the season (p<0.0001). In the herbaceous stratum a higher phytomass potential was found in the Herb Community (3977±2299 kg DM/ha in the rain season and 2451±3336 kg DM/ha in the dry season) explained by the effect of the community (p=0.011). The high variance in the potential phytomass is explained by the presence of rock outcrops where no vegetation was found, characteristic of Leptosols (Flores and Bautista, 2005). The potential phytomass contribution of the HC, due to the presence of herbs and grasses, could be a key element to complement the source of food for the cattle in the secondary subtropical rainforest, since grasses have been traditionally associated to livestock production because they are an important source of dry material, with regrowth capacity and resistance to grazing that may have good nutritional quality (Villegas et al., 2001). The medium sub-deciduous rainforest is characterized by a defoliation of between 50 and 75 % (Flores and Espejel, 1994), indicating that the presence of potential phytomass in the dry season could mean a strategic dietary resource for the survival of the cattle, in addition to the fallen leaves and husks (Pettit et al., 2011). Although traditional livestock production in the south of Yucatán is based on feeding with rainfed grasses (Osorio and Marfil, 1999), possibly the presence of areas in successional young stages (with grasses), intermediate (with woody), and mature (with developed trees), could be linked to grazing practices in the rainy and dry seasons. Since there are no reports available in the study sites of potential phytomass, the results obtained are very important to achieve a better exploitation of the fodder resource in these production systems.

Chemical-nutritional composition, ruminal degradability and metabolizable energy concentration of the fodder species

The chemical-nutritional composition of the dominant fodder species analyzed varied between 35 and 77 % in their NDF content; 5 to 27 % of RP; non-detectable, at 12.75 % of CT; from 49 to 94.75o% of DisDM at 48 h; and from 7.57 to 12.43, MJ of ME, with Senna uniflora standing out, with 94.66 % in DisDM at 48 h (Table 5). The ranges of nutritional values found here agreed with those found in other studies (Ayala et al., 2006; Palma et al., 2011), especially in contents of raw protein above 12 % in woody species and percentages of DisDM around 70 %. The high content of NDF in Poaceas (over 69 %) is characteristic of tropical grasses, except Lasciasis ruscifolia (Table 5), whose perennial characteristic and high dominance could make it strategic during the dry season, while the concentrations of nutrients and secondary compounds was quite diverse, which in turn defined digestibilities and metabolizable energy concentrations in a broad range of variation. This has also been found in other studies of diverse vegetation in communities subject to grazing (Velázquez et al., 2010; Flores y Bautista, 2012).

Table 5 Values of the chemical-nutritional composition, ruminal degradability, and concentration of metabolizable energy of the dominant fodder species in the medium sub-deciduous secondary rainforest during the rain season 2013.

FDN: Neutral Detergent Fiber; PC: Raw Protein; TC: Condensed Tannins; DisMS: Degradability in situ of the dry matter at 48 h; EM (MJ kg/MS): Metabolizable energy concentration expressed in mega joules per kg of dry matter. ND: Not determined.

Based on the dominance of fodder species reflected in the RVI (Table 3) and the values of chemical-nutritional composition obtained (Table 5), a trend was observed in the values of the species of the FC that suggests a significant offer of energy, due to the lower content of NDF, higher DisDM and concentration of metabolizable energy, which implies a higher nutritional contribution; although this plant community offers a lower amount of potential phytomass, it could be complementary to the contribution of dry matter of the herbaceous community. It is important to point out that for the exploitation of tree fodder species, they should be available for the animal, or else, be destined to fodder for cutting. On the other hand, the species with low concentrations of NDF, high DisDM and ME concentration could promote a higher voluntary consumption (Dulphy and Demarquilly, 1994) and a faster passage rate (Ku et al., 1999), which could represent a possible source of energy of fast ruminal availability that allows maximizing the microbial protein synthesis in the rumen, as well as increasing the contribution of microbial nitrogen to the small intestine (Sauvant and Van Milgen, 1995), while the presence of secondary metabolites in the plants evaluated could induce mitigation in the production of enteric methane when modifying the microbial populations in the rumen and, as consequence, modifying the products of fermentation (acetic, propionic and butyric acid) of rumen carbohydrates (Gerber et al., 2013), in addition to the nematicide effect, and which would contribute to decreasing the load of intestinal parasites (Hoste et al., 2006; Mueller, 2006). The fodder species found, clearly differentiated by type of community, may represent an offer of food for the bovine livestock with different nutritional characteristics that could be complemented throughout the year for a better distribution of the availability of fodder.

In this manner, the nutritional potential of the secondary vegetation described before constitutes a potential of use for grazing in this type of plant communities. Avoiding felling to induce the monocrop of improved pasturelands, when promoting this grazing in the natural vegetation, in addition to providing complementary fodder in critical times, allows its fodder species’ structure and diversity to foster a higher connectivity between fragments of primary vegetation; the very presence of secondary vegetation optimizes environmental services such as nitrogen fixing, phosphorus solubility, and improves the biological activity of the soil and offers habitat for wild fauna (Murgueitio et al., 2008; 2011).

Conclusions

The different successional states in the vegetation of the medium sub-deciduous rainforest influenced the quality and quantity of potential food for bovine livestock.

The successional state with greater time of abandonment presented a better nutritional quality, measured through the ruminal degradability and concentration of metabolizable energy, which is complemented in the amount of potential phytomass with the youngest successional states where the Poaceas dominate.

The vegetation of the intermediate states of succession in the dry season can be strategic for the survival of the livestock due to the higher abundance of fodder species that are resistant to drought, which is why the secondary vegetation offers sufficient food and of high quality in the different successional states of the sub-humid tropics, with adjusted animal loads for the yield of potential phytomass.

Literatura Citada

Achan G., Febles G., Ruíz T., and Noda A., 2011. Performance of tree species in two arboretums of the Institute of Animal Science. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 45 (4): 439 - 444. [ Links ]

Adjorlolo L., Amaning-Kwarteng, and Fianu F., 2004. Preference of sheep for three forms of Mucuna forage and the effect of the supplementation with Mucuna forage on the performance of sheep. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 36:145 - 156. [ Links ]

Alonso M. A., Torres F. J., Sandoval C. A., Hoste H., Aguilar A. J., and Capetillo C. M. 2009. Sheep preference for different tanniniferous tree fodders and its relationship with in vitro gas production and digestibility. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 151: 75 - 85. [ Links ]

Álvarez M., Córdoba S., Escobar F., Fagua G., Gast F., Mendoza H., Ospina M., Umaña A. M., y Villareal H. 2006. Manual de métodos para el desarrollo de inventarios de biodiversidad. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

Ankom Technology. S/F. Neutral Detergent Fiber in Feeds - Filter Bag Technique (for A200 and A200I). NDF Method Method 6. [ Links ]

Andrade H., Esquivel H., y Ibrahim M., 2008. Disponibilidad de forrajes en sistemas silvopastoriles con especies arbóreas nativas en el trópico seco de Costa Rica. Zootecnia Tropical. 26 (3): 289 - 292. [ Links ]

AOAC International, 2000. Official Methods of Analysis. 17th ed. AOAC Int., Gaithersburg, MD. [ Links ]

Ayala A. J., Cetina R., Capetillo C., Zapata C., y Sandoval C. A. 2006. Composición química-nutricional de árboles forrajeros. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Mérida, Yucatán, México. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277141987_Composicion_Quimica-Nutricional_de_Arboles_Forrajeros . Fecha de consulta: 20 de octubre de 2015. [ Links ]

Bello J., Gallina S., y Equihua M. 2001. Characterization and habitat preferences by white-tailed deer in México. Journal of Range Management. 54: 537 - 545. [ Links ]

Bautista F., Delfín H., Delgado M., y Palacio J. 2004. Técnicas de muestreo para manejadores de recursos naturales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología e Instituto Nacional de Ecología, México. http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/download/526.pdf Fecha de consulta: 25 de julio de 2015. [ Links ]

Bonham C, 1989. Measurements for terrestrial vegetation. 1st Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-71-04880-1. EUA. 352 P. [ Links ]

Cab F., Ortega M., Quero A., Enríquez J., Vaquera H., y Carranco M. 2015. Composición química y digestibilidad de algunos árboles tropicales forrajeros de Campeche, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas Pub. Esp. 11:2199-2204. [ Links ]

Castellón M., y Elías A. 2015. Evaluación del peso de inicio en toros en ceba con dietas basadas en foraje de Panicum maximum, cutícula de maní (Arachis hypogaea) y un suplemento proteico-energético. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Agrícola. 49:1 49:1 http://www.ciencia-animal.org/revista-cubana-de-ciencia-agricola/articulos/T49-N1-A2015-P23-ME-Castellon.pdf . Fecha de consulta 22 de noviembre de 2015. [ Links ]

Colwell R. K. 2013. Estimate S: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 9.1. [ Links ]

CICC. 2009. 5ª Comunicación Nacional ante la Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático. Comisión Intersecretarial de Cambio Climático. http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones/download/685.pdf . Fecha de consulta: 07 de mayo de 2015. [ Links ]

CICY. 2010. Flora de la Península de Yucatán. Catálogo de la Flora. http://www.cicy.mx/sitios/flora%20digital/indice_busqueda.php . Fecha de consulta: 18 de enero de 2015. [ Links ]

CONAGUA. 2015. Cominsión Nacional del Agua. Península de Yucatán. http://www.conagua.gob.mx/ocpy/ Fecha de consulta: 23 de noviembre de 2015. [ Links ]

Dulphy J. P., and Demarquilly C. 1994. The regulation and prediction of feed intake in ruminants in relation to feed characteristics. Livestock Production Science. 39: 1-13. [ Links ]

ECOCROP. 2007. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/GBASE/Default.htm . Fecha de consulta: 06 de diciembre de 2016. [ Links ]

Escamilla B. A., Quintal T. F., Medina L. F., Guzman A., Pérez E., y Calvo I. L. 2005. Relaciones suelo-planta en ecosistemas naturales de la península de Yucatán: comunidades dominadas por palmas. In: Bautista F, Palacio G editores Caracterización y manejo de los suelos de la península de Yucatán: Implicaciones Agropecuarias, Forestales y Ambientales. Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Instituto Nacional de Ecología. 159-172. [ Links ]

FAO. 2009. El estado mundial de la agricultura y la alimentación. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación. Roma, Italia. https://www.fao.org.br/download/i0680s.pdf . Fecha de consulta: 25 de mayo de 2015. [ Links ]

FAO. 2013. Tackling climating change through livestock. A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/i3437e.pdf . Fecha de consulta: 9 de agosto de 2015. [ Links ]

Ferguson G., Diemont A., Alfaro A., Martin F., Nahed T., Álvarez S., et al. 2013. Sustainability of holistic and conventional cattle ranching in the seasonally dry tropics of Chiapas, México. Agricultural Systems. 120: 38-48. [ Links ]

Flores S., y Espejel I., 1994. Tipos de vegetación de la Península de Yucatán. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Dirección General de Extensión. [ Links ]

Flores S. 2001. Leguminosae. Florística, Etnobotánica y Ecología. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Fascículo 18. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Yucatán, México. [ Links ]

Flores S., y Bautista F. 2005. Inventario de plantas forrajeras utilizadas por los Mayas en los paisajes geomorfológicos de la peninsula de Yucatán. In: Bautista B, Palacio G editores. Caracterización y manejo de los suelos de la península de Yucatán: Implicaciones Agropecuarias, Forestales y Ambientales. Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Instituto Nacional de Ecología, México. 209-219. [ Links ]

Flores S., y Bautista F. 2012. El conocimiento de los mayas yucatecos en el manejo del bosque tropical estacional: las plantas forrajeras. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad. 83(2): 503-518. [ Links ]

Garcia E., y CONABIO. 1998. Climas (Clasificación de Köppen, modificado por García), escala 1:1 000 000. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Mexico. [ Links ]

Gerber P., Hederson B., y Makkar H. 2013. Mitigación de las emisiones de gases con efecto invernadero en la producción ganadera. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación. Roma, Italia. UK. http://www.fao.org/docrep/019/i3288s/i3288s.pdf . Fecha de consulta: 13 de noviembre de 2015. [ Links ]

Gleen-Lewin D. C., Peet R. K., and Veblen T. T. 1992. Plant succession. Theory and prediction. Chapman & Hall. Cambridge, UK. 359 p. [ Links ]

González P., Torres J., and Sandoval C. 2014. Adapting bite coding grid from small ruminants browsing a deciduous tropical forest. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 17: 63-70. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez B., Ortiz D., Flores J., y Zamora C. 2012. Diversidad, estructura y composición de las especies leñosas de la selva mediana subcaducifolia del Punto de Unión Territorial (PUT) de Yucatán, México. Polibotánica. 33: 151 - 174. [ Links ]

Hoste H., Jackson F., Athanasiadou S., Thamsborg S. M., and Hoskin S. O. 2006. The effects of tannin-rich plants on parasitic nematodes in ruminants. Trends in Parasitology 22: 253-261. [ Links ]

Ku J. C., Ramírez L., Jiménez G., Alayón J. A., et al. 1999. Árboles y Arbustos para la producción animal en el trópico mexicano. En: Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en Latinoamérica. Estudio FAO Producción y Sanidad Animal 143, Roma, Italia. [ Links ]

Kovach L. 2007. MVSP-A MultiVariate Statistical Package for Windows, ver. 3.1. Kovach Computing Services, Pentraeth, Wales, U.K. [ Links ]

Jackson F., Barry T., Lascano C., and Palmer B. 1996. The extractable and bound condensed tannin content of leaves from tropical tree, shrub, and forage legumes. Journal of the Science Food and Agriculture. 71 (1): 103-110. [ Links ]

LEAD. 2006. The Livestock Environment and Development. Livestock long shadow. Environmental issues and option. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM . Fecha de consulta: 28 de octubre de 2015. [ Links ]

Lecco. 2013. TruMac CN. Carbon/Nitrogen Determinator. Instruction Manual. Version 1.3x. Part number 200-725 No. HQ-Q-994. Lecco Corporation. [ Links ]

López M., Rivera J., Ortega L., Escobedo J., Magaña M., Sanginés R., and Sierra A. 2008. Quintana Roo Nutritional composition and antinutritional factor content of twelve native forage species from northern Quintana Roo, Mexico. Técnica Pecuaria México. 46 (2): 205-215. [ Links ]

Magurran A. E. 1988. Ecological Diversity and its Measurement. London, Chapman and Hall. 178 P. [ Links ]

Makkar H., and Becker K. 1993. Vanillin-HCl method for condensed tannins: efect of organic solvents used for extraction of tannins. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 19 (4): 613-621. [ Links ]

Mizrahi A., Ramos M., and Osorio J. 1997. Composition, structure and mangament potential of secondary dry tropical vegetation in two abandoned henequen plantations of Yucatan, México. Forest Ecology and Mangement 94: 79-88. [ Links ]

Mueller-Dombois D., and Ellenberg H. 1974. Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. Jhon Wiley & Sons, New York. USA. 547 p. [ Links ]

Mueller, H. 2006. Review. Unravelling the conundrum of tannins in animal nutrition and health. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 86: 2010-2037. [ Links ]

Murgueitio, E., Ibrahim M., Molina H., Molina D., y Molina J. 2008. Ganadería del futuro: Investigación para el desarrollo. Fundación CIPAV. Murguetitio E., Cuartas C., y Naranjo J. Calí, Colombia. http://www.cipav.org.co/pdf/noticias/PaginasSSPCIPAV.pdf . Fecha de consulta: 10 de marzo de 2015. [ Links ]

Murgueitio E., Call Z., Uribe F., Calle A., and Solorio B., 2011. Native trees and shrubs for the productive rehabilitation of tropical cattle ranching lands. Forest Ecology and Management 261: 1654-1663. [ Links ]

Nahed J., Valdivieso A., Aguilar R., Cámara J., and Grande D. 2013. Silvopastoral systems with traditional mangament in southeastern México: a prototype of livestock agroforestry for cleaner production. Journal for Cleaner Production 57: 266-279. [ Links ]

NAS (National Academic Science). 1979. Tropical legumes: resources for the future. Washington D. C. 331 p. [ Links ]

Ørskov, E., Hovell F., and Mould F. 1980. The use of the nylon bag technique for the evaluation of feedstuffs. Tropical Animal Production. 5 (3): 195-213. [ Links ]

Osorio A., y Marfil A., 1999. Caracterización de la ganadería lechera del estado de Yucatán, México. Revista Biomédica 10, 217-227. [ Links ]

Palma J., Nahed J., y Sanginés L., 2011. Agroforestería pecuaria en México. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. México. [ Links ]

Pettit J., Casanova F., Solorio J., y Ramírez L. 2011. Producción y calidad de hojarasca en bancos de forraje puros y mixtos en Yucatán, México. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente. 17 (1): 165-178. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62917370015 . Fecha de consulta: 04 de diciembre de 2016. [ Links ]

Pinto R., Gómez H., Martínez B., Hernández A., Medina F., Ortega L., and Ramírez L. 2004. Forage pecies utility in silvopastoral system in the valley central of Chiapas. Avances en Investigación Agropecuaria. 8 (2):53-67. [ Links ]

Rico-Gray V., Chemás A., and Mandujano S., 1991. Uses of tropical deciduos forest species by the yucatecan maya. Agroforestry Systems 14: 149-161. [ Links ]

Rojas S., Olivares J., Quiroz F., Villa A., Cipriano M., Camacho L., and Reynoso A. 2016. Diagnosis of the palatability of fruits of three fodders trees in ruminants. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 3 (7): 121-127. [ Links ]

Romero A., and Duarte J. 2012. Identification and nutritional valuation of frequently consumed plant species by sheep and goat grazing on the Tatacoa desert, Huila, Colombia. Agroforestería Neotropical. 2 (1). 2012. http://repository.ut.edu.co/handle/001/1282 . Fecha de consulta: 04 de diciembre de 2016. [ Links ]

Sadi S., Shanmugavelu, Azizan A., Abdullah F., Wan M., and Humrawali K. 2015. Effects of Ischaemum rugosum-Gliricidia sepium diet mixtures on growth performance, digestibility and carcass characteristics of Katjang crossbred goat. Journal of Tropical Agricultural and Food Science. 43 (2): 179-190. [ Links ]

SAS (Satistical Analysis Systems Institute). 2000. Users Guide Statistic, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina. (Version 8,1). 646 p. [ Links ]

Sauvant D., and Van Milgen J. 1995. Dynamic aspects of carbohydrate and protein breakdown and the associated microbial matter synthesis. In: W. von. Englehardt S, Leonhard-Marek, Breves G, Diesecke D (eds). Ruminant Physiology: Digestion, Metabolism, Growhth and Reproduction. Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany. pp: 71-91. [ Links ]

Sørensen T. 1948. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biologiske Skrifter (K Danske Vidensk. Selsk. NS). 5: 1-3. [ Links ]

Sosa R., Sansores L., Zapata B., y Ortega R. 2000. Composición botánica y valor nutricional de la dieta de bovinos en un área de vegetación secundaria en Quintana Roo. Técica Pecuaria en México. 38 (2): 105-117. [ Links ]

Van Soest P. J., Robertson J. B., and Lewis B. A. 1991. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergen fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. Journal of Dairy Science. 74 (10): 3583-3597. [ Links ]

Vásquez F., Pezo D., Mora-Delagado J., y Skarpe Ch. 2012. Selectividad de especies forrajeras por bovinos en pastizales seminaturales del trópico centroamericano: un estudio basado en la observación sistemática del pastoreo. Zootecnia Tropical. 30 (1): 63-80. [ Links ]

Velázquez M., López O., Hernández M., Díaz R., Pérez E., and Gallegos S. 2010. Foraging behavior of heifers with or without social models in an unfamilar site containing high plant diversity. Livestock Sicence. 131: 73-82. [ Links ]

Velázquez M., López S., Hernández O., Díaz P., Pérez S., and Gallegos J. 2011. Chemical and nutritional characterization of different species native to a site grazed by calves in north Veracruz. Abanico Veterinario. 1 (1): 16-20. [ Links ]

Villegas D., Bolaños M., y Olguín P. 2001. Ganadería en México. I.5.1. Temas selectos de geografía en México. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Geografía. Plaza y Valdez Editores, SA de CV. 157 p. [ Links ]

Zamora P., García G., Flores J., y Ortíz J. 2008. Estructura y composición florística de la selva mediana subcaducifolia en el sur del estado de Yucatán, México. Polibotánica: 26, 39-66. [ Links ]

Zamora C., Flores G., y Ruenes M., 2009. Flora útil y su manejo en el cono sur del Estado de Yucatán, México. Polibotánica. 28: 227-250. [ Links ]

Received: May 2016; Accepted: November 2016

text in

text in