Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.14 no.4 Texcoco oct./dic. 2017

Articles

Financial evaluation with the real options methodology of an investment to produce chitosan based on shrimp waste

1 Colegio de Postgraduados. Carretera Federal México-Texcoco, km 36.5. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. México. 56230. (jbrambilaa@colpos.mx).

2 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Carretera los Reyes-Texcoco, km.13.5. Coatlinchán, Estado de México. México. 56250.

Enterprises in modern economies face the challenge of being profitable and reducing their ecological impact. A scientific, technological and economic effort is being made to substitute petrol products for products obtained from organic raw materials. Shrimp production (Peneus vannamei) generates 400 kg of waste per ton. Nowadays it is viable technically and economically to use this waste to produce chitosan that serves as a polymer to produce biodegradable materials. Investing in a shrimp and chitosan production system with shrimp waste is more profitable than remaining only in production. The financial evaluation of the shrimp-chitosan project with a traditional methodology of Net Present Value (NPV) must be complemented with the real options methodology that allows considering the volatility of the shrimp and chitosan prices in the analysis. The result is that a shrimp-chitosan project is more profitable (NVPTOTAL=$1 790 000) than if only shrimp is produced (NVP=$182 000). It is concluded that it is possible to increase the profitability of the shrimp productive chain through the treatment of its waste to produce chitosan.

Key words: biopolymer; waste; ecological impact; profitability; volatility

Las empresas de economías modernas enfrentan el reto de ser rentables y reducir su impacto ecológico. Se está haciendo un esfuerzo científico, tecnológico y económico para sustituir los petroproductos por productos obtenidos de materia prima orgánica. La producción de camarón (Peneus vannamei) genera 400 kg de desperdicio por tonelada. Ahora ya es viable técnica y económicamente usar ese desperdicio para producir quitosano que sirve de polímero para producir materiales biodegradables. Invertir en un sistema de producción de camarón y de quitosano con desperdicio de camarón es más rentable que mantenerse solamente en la producción. La evaluación financiera del proyecto de camarón-quitosano con la metodología tradicional de Valor Actual Neto (VAN) se tiene que complementar con la metodología de opciones reales que permite considerar en el análisis la volatilidad de los precios del camarón y del quitosano. El resultado es que un proyecto de camarón-quitosano es más rentable (VANTOTAL=$1 790 000) que si solo se produce camarón (VAN=$182 000). Se concluye que es posible aumentar la rentabilidad de la cadena productiva de camarón mediante el tratamiento de su desperdicio para producir quitosano.

Palabras clave: biopolímero; desperdicio; impacto ecológico; rentabilidad; volatilidad

Introduction

The way in which modern economies consume and produce does not allow giving value to the waste that is generated, and when it is disposed it causes problems of pollution and ecological impact. Waste is a residue of what cannot be or isn’t easy to use, and wasting is not exploiting something property, although technological advances and the pressure to contaminate less and reduce the ecological impact manage for high value products to be obtained from the waste. In fact, a new branch of economy arises, which is waste or circular economy (DEFRA, 2012; Lacy and Rutquist, 2015).

In the case of México, in 2013 the shrimp capture in open sea was 68 % and in aquaculture, 32 % (CONAPESCA, 2014). Waste is generated in the processing and consumption of shrimp. De Andrade et al. (2012) estimate that out of each ton of production, 400 kg are wasted and this organic matter is destined to municipal landfills. On the other hand, modern economies have used petroleum excessively, which is now the main source of pollution and climate change. Thus, in all modern economies a great effort is being made to move from oil-economy to bio-economy, which consists in substituting petrochemical products for products obtained from organic matter, such as biofuels, biomaterials, biopolymers, etc. (Brambila, 2011a). Recent scientific studies have shown that a polymer called chitin can be obtained from shrimp shell, which is a waste; it is insoluble in most organic solvents, although through a process of deacetylation it is possible to extract chitosan. Plastic films, gums, gels, threads, and capsules, among others, can be formed from this product (Rinaudo, 2006; Pillai et al., 2009; Miranda and Lizárraga, 2012). Chitin is considered to be the second most important biopolymer in the world (Támara et al., 2012; Pradeepa et al., 2014; Lárez, 2006).

The price of chitosan ranges between $700 000 to $8 000 000 per ton, depending on the purity and the market (Dupont, 2014). With data from 2014, shrimp is listed at $44 000 per ton in average. This price varies according to the size, the time of the year, whether it is from open sea or aquaculture, from the Pacific or Gulf region, and from states of the republic (INEGI, 2014). With the waste, the shrimp producer has a high-value byproduct and with it the possibility of reducing the ecological impact. The price of the products that substitute petroleum derivatives is volatile because it depends on technological innovation, on the new uses that are found for it and the petroleum price, so that if shrimp enterprises want to take advantage of their waste they must take into account the volatility of shrimp and chitosan prices when making an investment; the latter is correlated with the petroleum price. In order to perform a financial evaluation of a project that participates in a volatile market, it is no longer enough to use traditional methodologies, such as Net Present Value (NPV), Benefit-Cost (B/C) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR), but in addition the methodology of real options must be used (Copeland and Antikarov, 2001; Brach, 2003; Brambila, 2011b).

The real options valuation method considers that the management of a project makes decisions throughout its useful life to adapt to changing circumstances of the market and the technology. The management can decide at the time to broaden, reduce, abandon, continue, cease to be monovalent to become polyvalent (Brambila et al., 2013), and to enter new markets, such as biotechnology (Álvarez et al., 2012; Vedovoto and Prior, 2015). In the specific case of shrimp (Peneus vannamei), the management can decide to postpone, wait to know what is happening in the market, or invest in a shrimp waste processor to obtain and sell chitosan, taking into account the price volatility of both markets. It should be highlighted that the amount of chitosan that can be produced depends on the amount of shrimp obtained.

The objective of this study is to show that a shrimp company can be profitable if there is investment in a waste treatment system to obtain chitosan. In addition to being profitable for the enterprise, the ecological impact is reduced. The working hypothesis is that despite the volatility of the shrimp and petroleum prices, and therefore, of chitosan, it is more profitable to be in the shrimp-chitosan business that to be only a shrimp or chitosan producer.

Materials and Methods

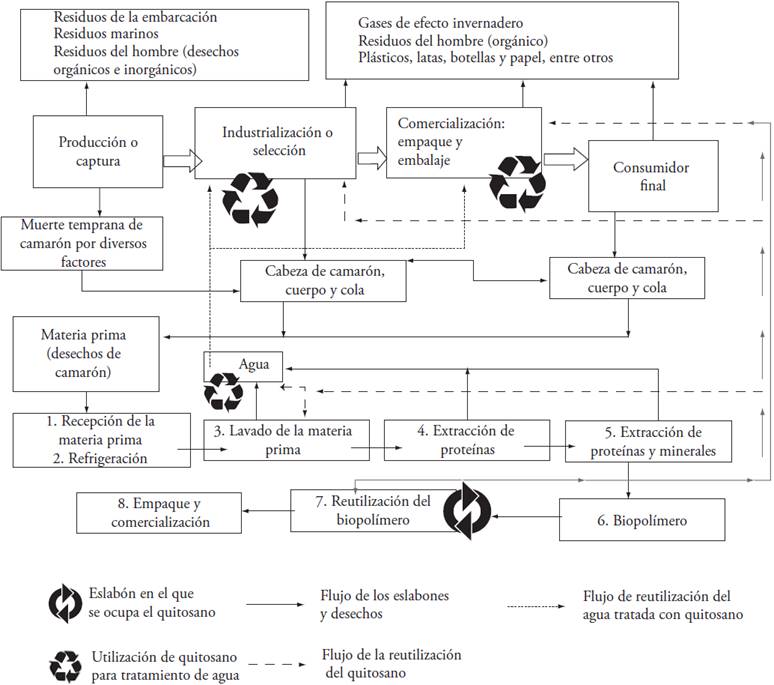

The financial evaluation of a project that has a main product, shrimp in this case, and the use of waste to obtain a byproduct, chitosan, requires understanding the whole shrimp-chitosan system. The shrimp-chitosan process is different from the one just for shrimp or just for chitosan because it allows the recycling of wastes and water. Figure 1 describes the shrimp-chitosan system. The reuse of chitosan is carried out in the seventh link of its productive chain.

Figure 2 exemplifies the shrimp-chitosan system where the shrimp shell is recycled to produce chitosan and water is recycled. In each one of the production systems, organic and inorganic wastes are generated. When recycling water, the environmental impact is reduced. The reutilization of shrimp shell as biomaterial is also shown. With the more dotted thick black arrows, the shrimp-chitosan link of the system is shown, where chitosan is reused and water is recycled. In the long term this system will transform into an integral production system where each one of the wastes from the links will become reintegrated into the global productive chain. What is expected is that the production costs will be reduced with this.

The traditional financial evaluation of a project to estimate its Net Present Value (NPV) consists in estimating the benefits and costs in each period and obtaining a cash flow that is updated to the starting period when using a discount rate that was 12 % in this study. The initial investment is subtracted from the sum in the present value of this flow and the result is the NPV. If this value is positive, it is recommended to invest in the project (Baca, 2010).

where: bi: Benefit in time i. ci: Cost in time i. I: Initial investment. ∂: Discount rate.

The data to calculate the NPV for shrimp were obtained from Trusts Funds for Rural Development (Fideicomisos Instituidos en Relación con la Agricultura, FIRA, 2009) for a ship of 16 ton/trip, with an average of six trips per season. The real prices were calculated with data from the National Statistics and Geography Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI, 2014), FIRA (2009), and the National Chamber for Aquaculture and Fishing (Cámara Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca, CONAPESCA, 2009). The fixed costs were estimated at $639 135 and the variable ones at $147 276 per season; the initial investment was considered to be $1 200o000. The breakdown and detail of the costs can be reviewed in FIRA’s informative bulletin (2009).

The data to carry out the NPV calculation for chitosan were obtained from Cerón (2010). An amount of 24 ton was considered and the real prices were obtained from INEGI (2014) and Shirai (2011). The fixed costs were estimated to be $4 822 683 and the variable ones $1 222 683; the initial investment that was estimated was $2 339 958. The breakdown and detail can be reviewed in Cerón (2010). The useful life of the projects was considered to be 10 years. The residual values are in the last year and are included to calculate the corresponding Net Present Values.

The statistical series of the 2000-2011 period of nominal shrimp prices from open sea was taken from the Master Plan for open sea shrimp from Sinaloa (CONAPESCA, 2009). The nominal chitosan prices for the 2000-2011 period were calculated with information from Shirai (2011) and discounted with the National Consumer Price Index (NCPI) annual accumulated base 2Q Dec 2010, published by the Bank of Mexico (Banco de México, BANXICO, 2014).

To obtain the real prices for shrimp and chitosan, the National Producer Price Index (NPPI) base August 2014 published by INEGI was used. The formula used to obtain the prices is:

where: PR: Real Price. PN: Nominal Price. INPP: National Producer Price Index.

Given that the shrimp and chitosan prices are very volatile, the financial evaluation of the shrimp-chitosan project must be complemented with the real options methodology. To apply the real options valuation method, it is required to estimate first the volatility of prices. This is done when calculating the continuous growth rate (in natural logarithms) of the prices from one year to another.

where rt: continuous rate of real price growth. ln: natural logarithm. Pt: real price in the year t. Pt+1: real price in the year t+1.

The volatility is measured with the standard deviation of the continuous rates of real prices.

where

With the Net Present Value and the standard deviation of the continuous change rates of real prices, the binomial tree of shrimp is formed.

In the case of the shrimp-chitosan system, the standard deviation was estimated with the Markowitz criteria for an investment portfolio (Ross et al., 2005).

where Γ2 : volatility of the shrimp and chitosan portfolio or variance of real prices of shrimp and chitosan. σ12: Volatility of real prices of shrimp or variance of real prices of shrimp. δ12: covariance between real prices of shrimp and chitosan. X1 : proportion of the total investment destined to the shrimp project. σ22: volatility of the chitosan prices or variance of the real prices of chitosan. X2: proportion of the total investment destined to the chitosan project. The proportions of the amounts of shrimp and chitosan were calculated through the following mathematical relations. X 1 : initial investment to produce shrimp/ Total investment (shrimp and chitosan). X 2 : initial investment to produce chitosan / Total investment (shrimp and chitosan).

For the calculation of binomial trees with real options, the methodology used by Copeland and Antikarov (2001), Brach (2003) and Brambila (2011b) was used, who point out that the real options are the right, although not the obligation of exercising an action during the project’s life. In our case, the real option that a shrimp enterprise has is to invest in a chitosan project and form a shrimp-chitosan system with water recycling and the raw material already mentioned. This is a right, but not an obligation. With the standard deviation (σ) the scenarios of the enterprise are formed when the prices are rising (up=eσ) and when the prices are decreasing (down=e-σ), where u is what increases the project’s value from a rise in prices, d is what lowers the value of the project from a decrease in prices, and e is the Euler number.

Since there is risk, the project’s value can increase or decrease and the probability of this happening is measured (Brach, 2003; Brambila et al., 2013):

where p: probability of an increase in the project’s value. 1-p: probability of a decrease in the project’s value. : risk free interest rate (average of real cetes).

A binomial tree of the value of the project is formed when increasing (u) or decreasing (d) in time (Figure 3).

Once all the nodes and a horizon for shrimp production are found, a binomial tree is formed as the real option of integrating the shrimp-chitosan system starting from the second year. For this purpose, the values in the nodes were calculated backwards until reaching the value of the real option of producing shrimp-chitosan (Brach, 2003; Brambila et al., 2013).

where VQC: Net Present Value in the current period. p: Probability of an increase in the project’s value. 1-p: probability of a decrease in the project’s value. l : risk free interest rate (average of real cetes). vu: net present value of an increase in the project’s value from a previous period. vd: net present value of a decrease in the project’s value from a previous period.

Mascareñas et al. (2004) and Brambila (2013) indicate that the total net present value of the project will be equal to the traditional net present value plus the value of the real option of being able to opt for the production of chitosan extracted from shrimp shell.

where VANTOTAL: total net present value. VAN: net present value or traditional net present value. OR: real option.

The distribution of project values in the last period was estimated, using the formula of binomial probabilities (Copeland and Antikarov, 2001; Brambila et al., 2013).

where B: probability of being in node n in the moment t. n: number of nodes in the period t. t: period evaluated=1, 2…, 10. p: probability of an increase in the project’s value.1-p: probability of a decrease in the project’s value.

The distribution of values from each period approaches a normal distribution, so the probability of the project having a predetermined value could be estimated, standardizing the values and using the Z tables of a normal distribution.

where: xi: predetermined value of the project. x: mean value of the project in the period t. σ: standard deviation of the project’s value in the period t.

The NPVs (traditional) are calculated for the case of shrimp and chitosan as separate projects and only the binomial tree of shrimp production was constructed. Then, it is considered that the shrimp enterprise exerts its right to integrate the shrimp-chitosan system in the second year and its binomial tree was built.

Results and Discussion

The NPV (traditional methodology) of the project for producing just shrimp was $ 182 000, so the project should be accepted. The discount rate in this project is 12 %; it takes into account the bank rate and the project’s risk (Table 1 and 2). For the chitosan project, the NPV was $ 1 727 000, so the project should be accepted.

Table 1 Dynamics of the project value for shrimp production (thousands of pesos).

| Valores/Año | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 182 | 198 | 216 | 236 | 257 | 280 | 305 | 332 | 362 | 395 | 430 | |

| 167 | 182 | 198 | 216 | 236 | 257 | 280 | 305 | 332 | 362 | ||

| 153 | 167 | 182 | 198 | 216 | 236 | 257 | 280 | 305 | |||

| 141 | 153 | 167 | 182 | 198 | 216 | 236 | 257 | ||||

| 129 | 141 | 153 | 167 | 182 | 198 | 216 | |||||

| 118 | 129 | 141 | 153 | 167 | 182 | ||||||

| 109 | 118 | 129 | 141 | 153 | |||||||

| 100 | 109 | 118 | 129 | ||||||||

| 91 | 100 | 109 | |||||||||

| 84 | 91 | ||||||||||

| 77 |

Note: the profitability indicators are σ=0.0861, μ=1.0899, d=0.9175, p=0.6628, 1-p=0.3372.

Source: authors’ elaboration with data from CONAPESCA (2009) and INEGI (2014).

Table 2 Dynamics of the project value for shrimp production with investment for the extraction of chitosan in the second year (thousands of pesos).

| Valores/Año | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1864 | 1943 | 4307 | 6070 | 8731 | 12869 | 19435 | 29940 | 46739 | 73452 | |

| 1834 | 1909 | 2385 | 3255 | 4459 | 6187 | 8780 | 12827 | 19310 | 29789 | ||

| 1880 | 1366 | 1880 | 2554 | 3441 | 4633 | 6305 | 8794 | 12714 | |||

| 749 | 1066 | 1490 | 2046 | 2759 | 3665 | 4833 | 6413 | ||||

| 559 | 814 | 1166 | 1638 | 2249 | 3014 | 3943 | |||||

| 403 | 601 | 885 | 1281 | 1813 | 2500 | ||||||

| 280 | 427 | 645 | 962 | 1411 | |||||||

| 187 | 291 | 449 | 687 | ||||||||

| 122 | 191 | 299 | |||||||||

| 78 | 123 | ||||||||||

| 50 |

Note: the profitability indicators are: σ=0.454, μ=1.5747, d=0.6351, p=0.4222, 1-p=0.5778.

Source: authors’ elaboration with data from FIRA (2009), CONAPESCA (2009), INEGI (2014) and Shirai (2011).

Now, if a shrimp-chitosan system is used with the corresponding recycling and with a real option in the second year of investing in a waste processor to obtain chitosan, the NVPTOTAL is $ 1 790 000 (Table 3). This result is confirmed in the real options literature for other types of projects (Fenichel et al., 2008; Támara et al., 2012; Vedovoto et al., 2015). Furthermore, the case may be that the NPV will be negative and if there are real options the Total Net Present Value can become positive (Hannevik et al., 2015).

Table 3 Probabilities of being above or below the initial Net Present Value in the tenth year.

| Proyecto | VAN (pesos) | Probabilidad por arriba (%) | Probabilidad por debajo (%) |

| Sólo camarón | $182 000 | 0.6628 | 0.3372 |

| Camarón- quitosano | $1 790 000 | 0.4222 | 0.5778 |

The probabilities in each case for the project (shrimp and shrimp-chitosan) to be in the year 10 above or below its initial NPV are contrasted in Table 3. Likewise, the earning values per type of project are reflected. The volatility of the prices of the shrimp project (σ=0.0861) and the volatility of the prices of the shrimp-chitosan project (σ=0.454) are shown simultaneously in the probabilities used for the calculation of each one of the scenarios (binomial tree).

The value of the real option of the decision to invest in the second year was $1 608 000 (Table 4). Investing in a shrimp-chitosan system is economically profitable, technically viable, and the waste and ecological impact are reduced.

Table 4 Comparison of earnings per productive activity.

Source: authors’ elaboration with data from binomial trees.

Conclusions

Chitosan production from organic shrimp waste is economically profitable in the long term (OR 2YEAR=$1 608 000). In the shrimp productive chain, wastes are an alternative for the generation of earnings additional to the ones obtained with the production. The expectation of products from bioeconomy, such as biomaterials, biofuels, bioplastics, nutraceuticals, and functional foods, among others, obtained from second generation raw material or from solid residues becomes an attractive option for income generation. Therefore, the use of shrimp shell for the extraction of a polymer of high value in the chemical-industrial market becomes a profitable option in shrimp production. It is concluded that chitosan production from shrimp shell wastes is economically profitable and of less ecological impact (less waste); this, despite the volatility of the shrimp and petroleum prices.

Literatura Citada

Álvarez Echeverría, Francisco Antonio, Pablo López Sarabia, y Francisco Venegas Martínez. 2012. Valuación financiera de proyectos de inversión en nuevas tecnologías con opciones reales. Contaduría y Administración. Vol. 57, Núm. 3, julio-septiembre. [ Links ]

Baca Urbina, Gabriel. 2010. Evaluación de proyectos. Sexta Edición. McGrawHill. México. 181-184 p. [ Links ]

BANXICO (Banco de México). Estadísticas. Índice Nacional de Precios al consumidor acumulado. http://www.banxico.org.mx. Página consultada 1 de Marzo de 2014. [ Links ]

Brambila Paz, José de Jesús. 2011a. Bioeconomía: Conceptos y Fundamentos, México, SAGARPA-COLPOS. 334 p. [ Links ]

Brambila Paz, José de Jesús. 2011b. Bioeconomía: Instrumentos para su Análisis Económico. México, SAGARPA-COLPOS. 312 p. [ Links ]

Brambila Paz, José de Jesús, Miguel Ángel Martínez Damián, María Magdalena Rojas Rojas, y Verónica Pérez Cerecedo. 2013. La bioeconomía, las biorefinerías y las opciones reales: el caso del bioetanol y el azúcar. Agrociencia. Vol. 27, Núm 3, Abril. [ Links ]

Brach, Marion. 2003. Real Options in Practice. John Willey and Sons. New York. 384 p. [ Links ]

Cerón, Emilio, Jorge Echeverría, y Karen Torres. 2010. Propuesta de automatización y control para un proceso de obtención de un polímero biodegradable llamado quitosano. México, IPN. 124p. [ Links ]

CONAPESCA (Comisión Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca). 2014. Estadística pesquera y acuícola de México. http://www.conapesca.gob.mx/. Página consultada: 26 de septiembre. [ Links ]

CONAPESCA (Comisión Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca). 2009. Instituto Sinaloense de Acuacultura (ISA), Comité Sistema Producto Camarón de Altamar de Sinaloa. Plan Maestro de camarón de altamar del estado de Sinaloa. México, CONAPESCA. [ Links ]

Copeland, Thomas, y Vladimir Antikarov. 2001. Real Option: a Practitioner’s Guide, New York, Texere. 215 p. [ Links ]

De Andrade Sânia, MB, Rasiah Ladchumananandasivam, Brismak G da Rocha, Débora D Belarmino, y Alcione O Galvão. 2012. The Use of Exoskeletons of Shrimp (Litopenaeus vanammei) and Crab (Ucides cordatus) for the Extraction of Chitosan and Production of Nanomembrane. Materials Sciences and Applicationol. Vol 3. num. 7, july 2012. [ Links ]

DEFRA (Departament of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs). 2012. The economics of waste and waste policy. Reino Unido. 42p. [ Links ]

Dupont. 2014. Plásticos, polímeros y resinas. http://www.dupont.mx/ . Página consultada: 5 de Junio de 2014. [ Links ]

Fenichel, Eli, Jean Itasao, Michael Jones, y Graham J. Hickling. 2008. Real options for precautory fisheries management. Fish and Fisheries. Vol. 9. [ Links ]

FIRA (Fideicomisos Instituidos en Relación a la Agricultura). 2009. Situación actual y perspectivas del camarón en México. Núm 3, Año 2009. http://www.fira.gob.mx/ . Página consultada: 10 de septiembre de 2014. [ Links ]

Hannevik, Jorgen, Magnus Naustdal, y Henrik Struksnaes. 2015. Real options valuation under technological uncertainty: A case study of investment in post-smolt facility. Noruega, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 125 p. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 2014. Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor 2Q agosto 2014. http://www.inegi.org.mx/ . Página consultada: 17 de septiembre de 2014. [ Links ]

Lacy, Peter, y Jakob Rutquist. 2015. Waste to Wealth: The circular Economy Advantage, New York, Palgrave Macmillan. 266 p. [ Links ]

Lárez Velásquez, Cristóbal. 2006. Quitina y quitosano: materiales del pasado para el presente y el futuro. Avances en Química. Vol. 1, Núm. 2. [ Links ]

Mascareñas, Juan Manuel, Prosper Lamothe Fernández, Francisco J. López Lubián, y Walter de Luna Butz. 2004. Opciones Reales y Valoración de Activos: Como medir la Flexibilidad Operativa en la Empresa. Madrid, Pearson Educación. 238 p. [ Links ]

Miranda Castro, Patricia, y Eva Guadalupe Lizárraga Paulín. 2012. Is Chitosan a New Panacea?. Areas of Application. In: Desiree Nedra Karunaratne (coord). The Complex World of Polysaccharides. India. InTech. pp: 1-44. [ Links ]

Pillai, CKS, Paul Willi, and Sharma Chandra. 2009. Chitin and Chitosan polymers: Chemistry, solubility and fiber formation. Progress in Polymer Science. Vol. 34. [ Links ]

Pradeepa, GC, Yun Hee Choia, Yoon Seok Choia, Se Eun Suha, Jeong Heon Seonga, Seung Sik Chob, Min-Suk Baec, and Jin Cheol Yooa. 2014. An extremely alkaline novel chitinase from Streptomyces sp. CS495. Process Biochemistry. Vol. 49, Núm. 2. [ Links ]

Rinaudo, Marguerite. 2006. Chitin and Chitosan: properties and applications. Progress in Polymer Science. Vol. 31. [ Links ]

Ross, Stephen, Randolph Westerfield, and Jeffrey Jaffe. 2005. Corporate finance. McGrawHill. Boston. Sexta edición. 243 p. [ Links ]

Shirai Matsumoto, Keiko. 2011. Producción de quitina y quitosano: nuevo proceso biotecnológico para la obtención de quitina y quitosano. México, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. 40 p. [ Links ]

Támara Ayús, Armando Lenin, y Raúl Enrique Aristizábal Velásquez. 2012. Las opciones reales como metodología alternativa en la evaluación de proyectos de inversión. Ecos de economía. Vol. 16, Núm. 35, julio-diciembre 2012. [ Links ]

Vedovoto, Graciela Luzia, y Diego Prior. 2015. Opciones reales: una propuesta para valorar proyectos I+D en centros públicos de investigación agraria. Contaduría y Administración. Vol. 60, Núm. 1, enero-marzo, 2015. [ Links ]

Received: September 2014; Accepted: October 2016

texto en

texto en