Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.14 no.3 Texcoco jul./sep. 2017

Articles

Social networks and women organized for sheep production in Salinas, San Luis Potosí

1 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo. Km. 36.5 Carretera Federal México-Texcoco, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 56230. (luzmaph@colpos.mx, nunezej@colpos.mx).

2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potosí, Agustín de Iturbide 73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí. 78622. (benjamin@colpos.mx).

The dynamics of agricultural and livestock production units, managed by groups of organized men and women producers, represent the result of collective abilities for management and distribution of inputs of organization and trust. This allows characterizing the organizational profile with which these social groups are mobilized and locating the elements or actors that are central in the distribution of the benefits of the organizations. The Social Network Analysis (SNA) facilitated the analysis of the groups in function of their organizational quality and to identify, through the analysis of the exchange of the input of trust between women sheep producers, the possibility of establishing social network processes through actors with the potential of connecting different work groups. The groups analyzed showed an incipient organization fed by kinship processes and relational diversity that moved from the centralization of social prominence to the location of actors that linked different groups.

Key words: trust; cooperation; organization; women sheep producers

La dinámica de las unidades de producción agropecuaria, gestionadas por grupos de productoras(es) organizadas(os), representa el resultado de capacidades colectivas de gestión y distribución de insumos de organización y confianza. Esto permitió caracterizar el perfil organizativo con el que se movilizan estos grupos sociales y localizar aquellos elementos o actores que son centrales en la distribución de los beneficios de las organizaciones. El Análisis de Redes Sociales (ARS) facilitó el análisis de los grupos en función de su calidad organizacional e identificar, por medio del análisis del intercambio del insumo de confianza entre productoras de ovinos, la posibilidad de establecer procesos de red social a través de actores con el potencial de vincular a diferentes grupos de trabajo. Los grupos analizados mostraron una incipiente organización nutrida de procesos de parentesco y diversidad relacional que se desplazó desde la centralización de la prominencia social hasta la ubicación de actores que vincularon a grupos diferentes.

Palabras clave: confianza; cooperación; organización; ovinocultoras

Introduction

The process of correlation at the glocal level (Robertson, 2003) reveals that societies are systems in continuous exchange of information flows (Castells, 2001). This has generated a qualitative change in the vision regarding rural producers, from considering them as isolated subjects to communities in the search for sources of information about prices, markets, brokers, other producers, agricultural innovations, financing, traditional medicine training, and even religion (PNUD, 2001:34-35). This change has allowed considering rural development within a process that reformulates the original proposals and scales of the process of technology transference, knowledge and innovation for the rural environment. Within this context, the creative potential of these peasant communities continues to come up through innovative ways to communicate in the community and to produce rural knowledge that manage to reinforce their food production systems and income. The analysis of this type of community elements allows discerning social structures of reticular type that have potentiated the rural communities’ ability to survive, and even to improve their standards of living. An example of this are migration networks, community mechanisms that can foster the abilities of production and inventiveness of the rural communities, destining the remittances sent for purposes such as purchase of lands and real estate, small family businesses and agricultural units, community works, sponsorship of civic or religious festivities, among others (Torres, 2000).

Organization and social network

These community structures point to dynamics that drive subjects to participate in specific social groups, mediated through positions and feelings of identification, recognition and belonging, implying a compliance to inner processes of the groups to establish social equilibrium, economic dynamism and identity (Cuellar, 2009:4). In this way, the notion of belonging to a group is mediated through the perception of subjects of being under conditions of equality before their peers, perceiving an individual and collective benefit, guarantee of greater security and protection in the future (Hopenhayn, 2007:10), as well as the promotion and recurrence of this sense of belonging (Vivero, 2007:1) and the mutual support for the sake of achieving common objectives (Cuchillo, 2010:1). At the moment when the value of one of these elements depreciates, the subjects perceive their social belonging as being risked.

This leads to considering the concept of organization as the instrument to address the social conglomerates as organic units with particular characteristics. This is because the organization manages to decrease transaction costs, property negotiations, planning and execution of projects, institutional arrangements, etc., fostering the access to markets, services, and supplying capacities for the construction of public goods and for social benefit (Flores and Rello, 2002), defending interests of the community and easing the agreement (Chiriboga, 2003). Likewise, the organization allows the communities to demand, mobilize and manage resources (FAO, 1994), negotiate before public or private entities, as well as facilitate the channeling of benefits from development policies and programs (Contreras, 2000:5). Thus, the organization is the undeniable expression of a specific social capital and it expresses the existence of certainties and understandings between members (Gordon, 2005). The origin of the organizations can be diverse, although Castaños (1987) points to two types: a) through a process to satisfy requirements of a legal order, or b) as a result of traditions or rural culture that arise from the need to assemble in groups.

This indicates that the organization is conceptualized as a result of an inner dialectic between its members, although it is rarely pointed out that this dialectic is expressed by a subsystem of processes and dynamics that take place, under mutual agreement, between subjects to establish exchanges, complicities, adhesions, empathies, reciprocities, common interests, etc. That is, the analysis of the organization does not point to the multiple social combinations of these elements as entities that allow their reticular nature as social event and space. In this direction, each and every one of the organizations which could be discussed is nothing but the corollary of a reticular weave allowed by the combination and recombination of those elements of sociability. That is, the organization is a state and part of the social continuum of correlation and communication of individuals. In this sense, the concept of organization becomes insufficient to explain the dynamics of the conformation of the social scaffolding, especially in the scope of rural groups, so the concept of social network is suggested to complement this perspective.

A social network is conceived as a formal and defined system of information exchange based on a mutual agreement between the parts that integrate it (Nuñez, 2008:94). The foundation of these reticular systems is generated by the common interest in sharing and a consensual integration, so that inputs such as trust are vital for their continuity, to the degree that any experience of integration or social conglomerate is determined, in the first place, by the play of interpersonal connections of the subjects and their later and necessary redundancy (White et al., 2000). This type of social constructs can allow a horizontal management of social inputs, producing the possibility of a higher margin of participation, greater information and knowledge, and even the social differentiation of the subjects. In fact, the actors of a network acquire social roles according to the form and type of inputs that they manage, so they can actually fulfill punctual functions such as: organizers, managers, innovators, designers, undecided, adopters, communicators, integrators, breakers, among other functions (Nuñez, 2008: 95).

Inputs for social networks

The social scaffolding that sustains the community activities is directly linked to the process of social synergy, since it allows building support structures based on the networks of relationships that they seek, according to White et al. (2000), maximizing the distribution of wealth instead of protecting the capital accumulated, whether within a household, the family or any other small social group, although these networks also seek to protect, consolidate and broaden the result of this distribution; therefore, also of the economic and social capital accumulated and reproduced.

These community structures are nurtured through inputs that are hardly measurable, but their simple absence makes impossible the possibility of social sustenance. Among these the following can be distinguished: exchanges, cooperation, solidarity, recognition, filiations, empathy, reciprocity, communication and trust, among others (Molina and Alayo, 2005: 303). This last input is a powerful social reactive insofar as it allows the subjects to establish and sustain personal connections and, therefore, the experience of social cohesion (Helly, 2002: 95) and of belonging to an organization and identity (Longo and Cejas, 2003: 4). In relation to this, Buciega and Esparcia (2013) suggest that the input of trust is useful to analyze and establish groups, teams and associations for rural development, although it should be analyzed through the cohesion, density of communication, existence of relationships, closeness, correlation, homophily, intermediation between subjects, previous common experiences of assembling and organization, among others.

In this context, trust points to conciliation between collectives and one of its indicators happens through the exchange of social inputs established between two or more individuals, through the frequency and intensity of these exchanges. These are generated in an environment nurtured by values of familiarity, security, tranquility, hope, intention, frankness, certainty, credit and protection. In this direction, Landazábal et al. (2009) point out that trust is a necessary element to build social structures and generate properties of resilience in face of adverse situations, and is part of a more complex social construct originated in the processes of socialization, institutionalization and informal education, which allows generating collective learning acquired in the sociability typical of family networks, norms, values and cultural practices, learning expressed in concrete actions such as respect for the political and community positions, as well as participation in community work: faenas, tequios, fajinas, fatigas, tandas, etc. (González, 2012). In this sense, Santos (2015) infers that the construction of this input of sociability is produced where there are particular conditions such as: timely access to information and reliable knowledge, conditions of equity, accessible language. In the case of rural producers this input is expressed, for example, when farmers ask to borrow money to expand, when they were advised to do it by people they trust (Santos, 2015). Trust is a social construction that is activated in face of the presence of a social background of reciprocity, solidarity and cooperation around individuals. Although, as Perea et al. (2014) point out, this value of trust is differentiated in issues of gender since, in contrast with men, women use and share among them more innovations and form broader women producers’ networks, so that community mechanisms of wider social support and more numerous are built: their daily life is developed more in the community, so they are forced to seek help from other women producers, exchange information, seeds, and collaborate continually to solve problems in the community (access to public services), are more altruistic, and work better in teams for the benefit of their communities. That is, they build more solid social capital abilities that allow them to cooperate towards objectives in common.

Networks and social capital

With regards to the previous, social capital is expressed through joint actions carried out, by mutual accord, in a community, in order to fulfill specific collective objectives or attain resources of a different nature, so it is presented as a set of abilities of empathy and social support, managed in a structural way; that is, through the network behavior. In this direction, social capital comes about directly from collective processes, structured and more or less institutionalized, which allow one or another community to go in one or another direction (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1990; Durston, 2003). On the other hand, this ability acquires diversified behaviors according to the structural and organizational levels in which it is activated. In this regard, Buciega and Esparcia (2013) point out that social capital is a resource that experiences variations and can decrease or increase influenced by different factors, so they propose that social capital be analyzed in a typological manner in issues of rural development, since there is: a) social capital of cohesion that is derived from reticular dynamics inside the groups (density, centralization, existence of relationships, nearness, relationships of trust, homophily); and b) social capital that builds bridges between subjects with different characteristics (groups, associations, organizations, etc.) where the indicators would be density and existence of relationships between actors that belong to the two entities, as well as intermediation and compounding quality. In this sense, Flores and Rello (2001) indicate that, practically, each organizational level of any community has the potential of structuring collective abilities susceptible of being capitalized socially, so there can be talk of countless social capitals (entrepreneurial, school, civic, community, sanitary, of public character, private, etc.) with a different reach in decision making, seasonality (in the short, medium or long term), and their results can be random. In this same context it should be taken into account that the existence of social capital in and of itself does not represent the most important capital to make dynamic and improve social relationships, although it could come to play this role, together with other capacities, resources and under certain socioeconomic conditions (Flores and Rello, 2001).

The productive reconversion program for bean in the Potosino-Zacatecano Highlands

The municipality of Salinas, San Luis Potosí, has as one of its most important activities livestock production. According to INEGI (2007), the most important herds in descending order are sheep (22 046 heads), cattle (15 921 heads), goats (5996 heads) and pigs (2916 heads). It should be mentioned that in the case of sheep the municipality represents the second place with highest number of heads of livestock in the state, only under the municipality of Villa de Ramos, which has 27 839 heads (INEGI, 2007). Commerce of the products obtained from bovine and porcine livestock is carried out in the local market; the commercialization of sheep livestock is the most important one and, even when it is local, it is carried out with local and outside butchers and it is important due to the volume of livestock heads in the region. This activity has importance practically in all of the rural localities of the municipality.

Derived from this, in 1977 the Productive Reconversion Program for bean arises in the Potosino-Zacatecano Highlands, implemented by Colegio de Postgraduados (CP), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Production, Fishing and Food (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación, SAGARPA), in the municipalities of Pinos, Zacatecas, and Salinas, San Luis Potosí. With this program it was sought to promote, together with the inhabitants, local organizations and institutions, actions for the formation and development of bean and sheep value chains, in order to achieve their competitiveness (CP, 2010). An element of this proposal was the project of Constitution of rural production units for women producers of dairy sheep in the municipality of Salinas, San Luis Potosí, and Pinos, Zacatecas, seeking to integrate the female population that carried out its activities without participating in any form of organization. For this purpose, eleven groups of women were formalized into rural production societies (RPSs), one of them in the municipality of Pinos and the rest in different localities of the municipality of Salinas. The groups of women sheep producers received training regarding technical aspects of sheep breeding, as well as themes of personal and organizational development, trying to reinforce the bonds of trust and cooperation between them and towards their communities.

As a result of the training that these groups received, the opportunity to analyze their constitution came up, from the degree and intensity of their own integration, hoping that relationships had been established which allowed improving trust and communication between the members, commitment with the organization, and its perception within the community. In this sense, the objective of this study is to analyze the social structure achieved by these groups of women sheep producers through the social input of trust in order to determine: a) emerging patterns of organization between the groups in question; b) the way in which they relate to their community; and c) to identify, within the groups, the key actors that can influence the better functioning of the group and that allow establishing strategies to be followed with each group to contribute to their consolidation and in the fulfillment of their objectives.

The hypothesis that is set out is that there is certain integration in the organizations that makes their functioning possible, but it has not been possible to consolidate networks among the organizations that allow benefitting to a higher degree their members and the communities where they are developing.

Methodology

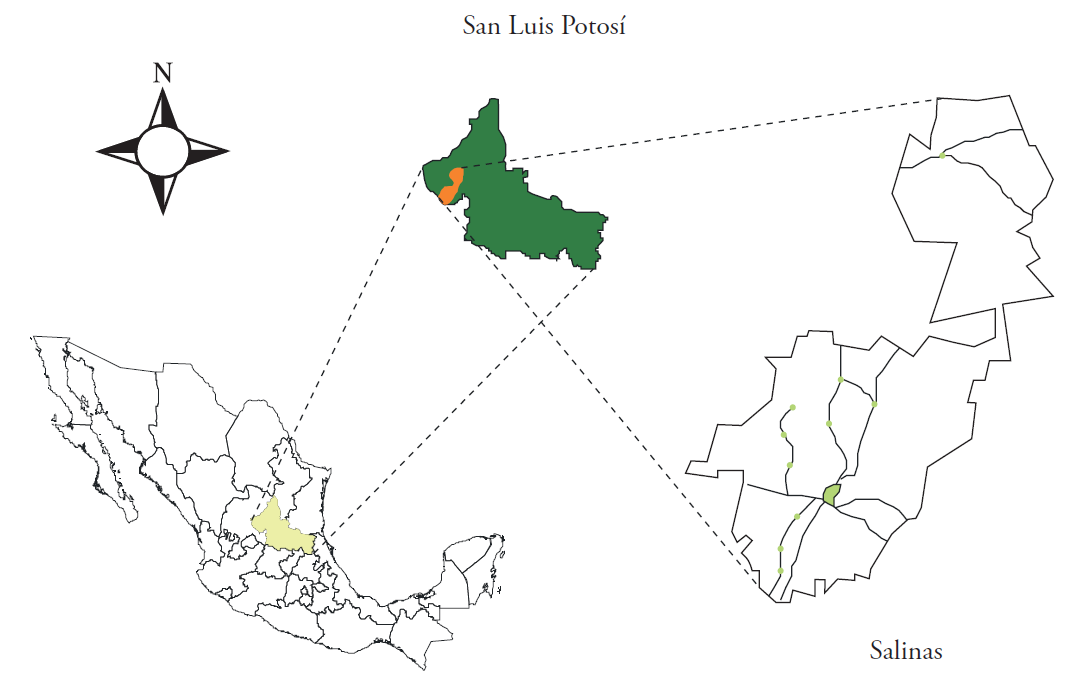

The study was focused on analyzing the integration of 11 organizations of rural production devoted to sheep breeding. These were located in the localities of: Conejillo, La Reforma, Diego Martín, San José de Punteros, La Palma Pegada, Salitrillo, El Potro and La Paz, belonging to the municipality of Salinas, San Luis Potosí (Figure 1). The actions for the formation and development of the bean and sheep value chains carried out within the Productive Reconversion Program of the Potosino-Zacatecano Highlands covered training on technical aspects of sheep breeding, as well as themes of personal, entrepreneurial and community nature, in order to generate correlation dynamics that could derive into manifestations of social capital in the groups generated.

This opened the possibility of identifying diverse social affinities related to the input of trust and allowed driving and identifying the conformation of 11 groups of women sheep producers, which are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1 Rural Production Societies in the municipality of Salinas, San Luis Potosí.

| Nombre de la organización | No. Integrantes |

|---|---|

| Agronómica Borrecos | 9 |

| Ganaderas Comprometidas | 11 |

| 10 Corazones | 8 |

| La Estrella de Salitrillo | 8 |

| Ovinocultoras El manantial del Potro | 8 |

| Ovinocultoras de San José Punteros | 13 |

| Las Trece Estrellas | 12 |

| Ovinocultoras Region Palmeña | 9 |

| Productoras de ovinos La Veta | 7 |

| El Gran Cordero | 10 |

| Derivados El Santuario del Nazareno | 14 |

Information gathering was carried out in May 2011. Of the 109 women that make up organized groups, 97 were interviewed. From this appraisal it is deduced that these emerging organizations are made up in average by nine members, each one with an average age of 38 years. With regards to schooling, 40.21 % studied for six years and 44.3 % for nine years; only five have university studies and one of the interviewees has post-graduate studies. The main activity that they are devoted to is the household (93 %) followed by helping in agricultural and livestock activities (55 %). Most of the interview respondents were married.

The methodology for this research was with a mixed approach, of transversal descriptive type. The instrument used to gather the information was the questionnaire applied through the interview. This allowed obtaining information about the following variables: trust, commitment, communication, participation in other organizations, and relationship to the community, trying to identify the intensity of the relationships established in the study groups. On the other hand, this input was systematized and its recurrence among women sheep producers was measured through observing the frequency in the number, intensity and type of exchanges that took place around the themes of community, family economy, work and personal issues. For the latter, a value was generated for the number of exchanges carried out. The minimum value was 1, if the exchange was about a single theme; and the maximum 4, if the exchange contemplated the four themes mentioned.

For the analysis and measurement of this information, the Social Network Analysis (SNA) was used, structuralist instrument that allows various angles (Navarro and Salazar, 2007) and a visualization about the behavior of complex human systems. This allows gaining access to the social dimensionality of the structures of human agglomeration, from the study of the relationships established and the explicative attributes that sustain any community (Molina et al., 2006).

These relationships were analyzed with the categories of centrality: Nodal Degree (Degree) and Degree of Intermediation (Betwenness). In relation to this, the Nodal Degree is defined as the number of actors who are directly linked to a specific actor.

The mathematical expression that allows its calculation is (Freeman, 1979):

where A ij : matrix that connects the nodes i and j; d i : centrality (degree) of the actor in question.

In turn, the Degree of Intermediation is the measure of centrality that points to the frequency with which a node appears as possible connection between any pair of nodes that are not directly linked (Wasserman, 1994; Verd and Olive, 1999). The calculation of this measure of centrality is carried out through the following equation (Freeman, 1979):

where g k : Degree of Intermediation (Betweenness); g ij : number of geodesic distances (number of links of one actor to another until reaching the target actor) from node i to node j; g ikj : number of links there are between i and j and which go through k.

On the other hand, the name of the women sheep producers was substituted by initials of their own names, in order to facilitate the visualization between actors and groups analyzed. The information obtained allowed the construction of graphs with the UNICET software.

Results and Discussion

Through the CP, campus San Luis Potosí, the 11 groups of women sheep producers received training to develop entrepreneurial abilities and team work. The objectives were: a) making women sensitive to their current condition in their communities, the notion of social organization through communication, conflict resolution, cooperation and social solidarity as factors of personal and community development; and b) consolidating and strengthening the relationships between members of each organization, recognizing the importance of team work and easing the management of the organization by providing them with the tools for this purpose. In this regard, Requena (2004) points out that the processes that generate social relationships and trust are defining for a higher standard of working life, which generates positive effects both for the individual and for the organization.

One of the elements of success of productive organizations is the presence of social capital, referring to the bonds of cooperation and trust, solidarity networks and all associative forms that serve as an expression of the capacity for collective action (Rello and Flores, 2001), where the trust, the kinship relationship, the learning prior to the collective action, and the institutional culture of the group are the basis (Berdegué, 2000), although the construction of social networks evolves into social capital when the human conglomerates manage to express, from common agreement, civic virtues, willingness for community commitment and cooperation (Porras and Espinoza, 2005).

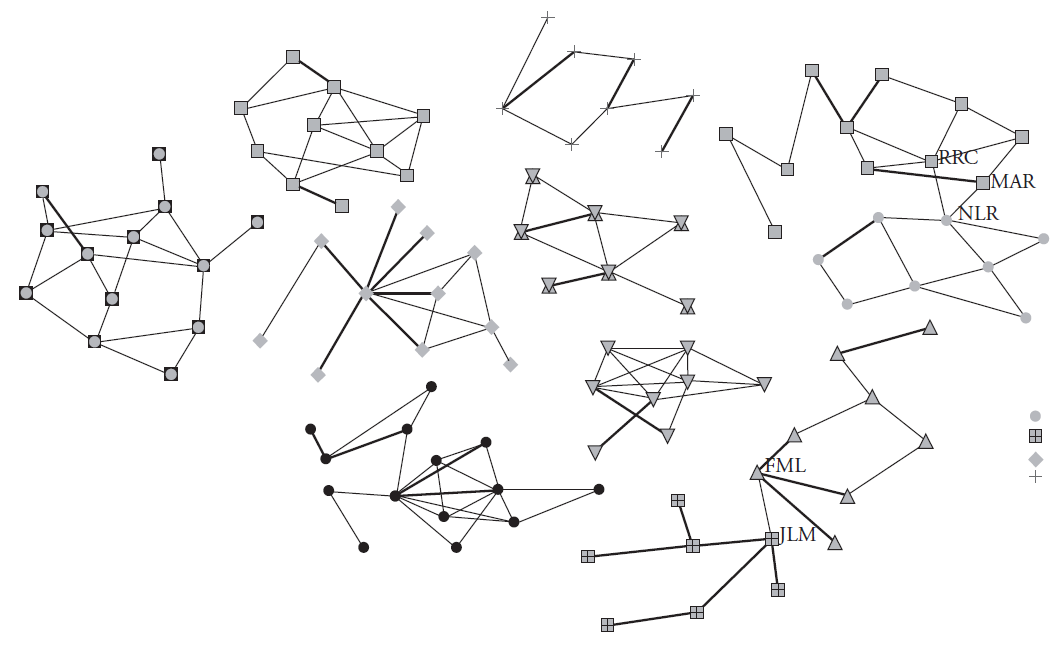

Within this context, the application of the SNA allowed distinguishing, in the 11 groups of women sheep producers analyzed, through geometric identifiers, structures of communication and correlation, formed by relationships of friendship and trust to share information about their community, family economy, work and personal issues. In this direction, the intensity of the bonds of friendship and trust established between the participants are distinguished according to the thickness of the link between actors: the thicker the link, the more themes were exchanged; therefore, there was more trust. According to Figure 2, the groups Derivados el Santuario del Nazareno ( ), Ovinocultoras de San José Punteros (

), Ovinocultoras de San José Punteros ( ) and El Gran Cordero (

) and El Gran Cordero ( ) are the ones where more bonds of trust between participants are present. Even when it can be seen that in Treces Estrellas (

) are the ones where more bonds of trust between participants are present. Even when it can be seen that in Treces Estrellas ( ) and La Estrella del Salitrillo (

) and La Estrella del Salitrillo ( ) there are solid bonds of trust, there is no diversification or communication with the other members of the group. The organizations where less bonds of trust were observed are: Productora de Ovinos la Veta (

) there are solid bonds of trust, there is no diversification or communication with the other members of the group. The organizations where less bonds of trust were observed are: Productora de Ovinos la Veta ( ) and Agronómica Borrecos (

) and Agronómica Borrecos ( ).

).

In this regard, Anheier and Kendall (2002) point out that members of the organizations rooted in communities with geographical proximity, with shared interests or values, understand the living situations, aspirations and problems of other members, favoring trust and cooperation, so that the intensity of the link is related, with higher interaction, in themes of inner cohesion and kinship. In this direction the interview respondents mentioned having greater trust with friends to speak of the economic theme (46 %), work (44 %), and about the community (46 %), while to address personal themes they mentioned having greater trust with family members (46 %). It should be mentioned that 50 % of the members of these organizations have a family member within the organization that they belong to; in fact, the figure of the husband stands out as the first receptor of these themes (38.67 %) and women friends as the second actor (14.93 %), followed by daughter, sister and mother, among others. In this regard, Brugué, Gomá and Subirats (2002) point out that kinship is one of the relationships of proximity where the networks with strongest links are formed.

Centrality (Degree and intermediation) in 11 RPS for sheep production

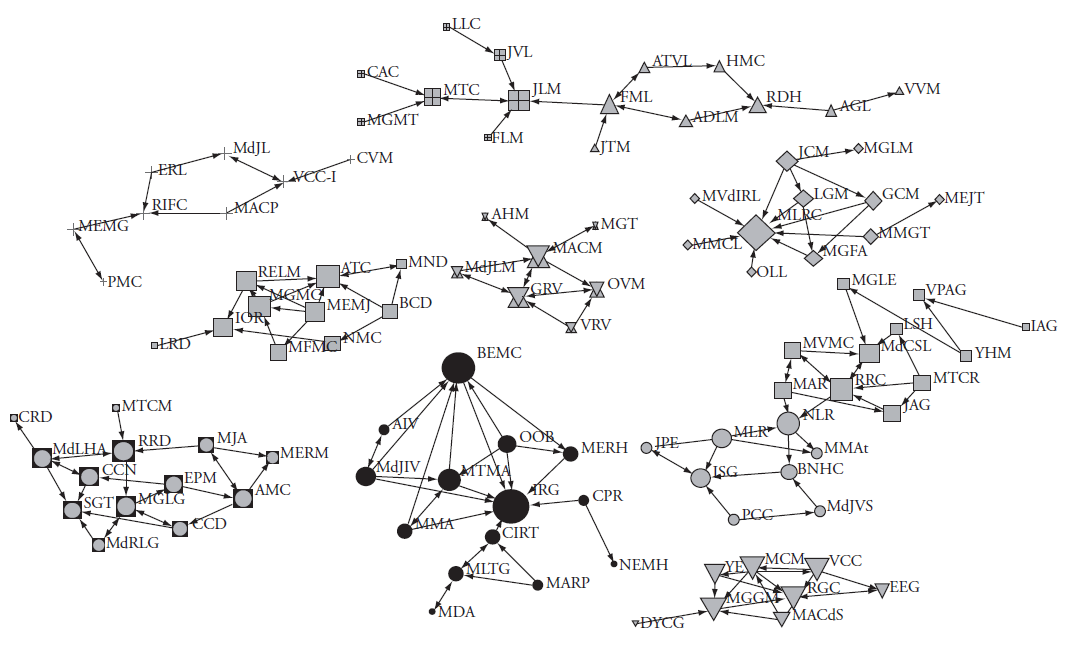

In this study, participants with higher nodal (or correlation) degrees were observed; therefore, better linked and with greater possibilities of having access to other members of their respective groups (Figure 3 and Table 2). Regarding this, Choucri (2001) points out that a reticular space with adequate functioning needs the presence of members who function with effective, institutional and individual ability to carry out specific and essential tasks. In relation to this, defining the themes in which more links take place allows identifying members, with which strategies can be addressed in various senses. Therefore, women who presented higher correlation in terms of trust to deal with economic issues can influence the group to establish finance mechanisms; in turn, those who have influence on the group in technical aspects can be a reference to the group and divulge innovations. Gayen and Raeside (2010) mention that interpersonal communication is identified as essential to persuade the average receiver to adopt an innovation, especially communication from peers such as friends and neighbors.

Table 2 Actors with the most outstanding nodal degrees (Degree) in the RPS.

| SPR | Prod* | Degree | SPR | Prod* | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivados el Santuario del Nazareno | IRG BEMC |

8 7 |

Ganaderas Comprometidas | RRC MdCSL |

4 4 |

| Ovinocult. Sn José Punteros | RRD MdLHA CCM AMC SGT MGLG |

5 4 4 4 4 4 |

10 Corazones La Estrella de Salitrillo Región Palmeña |

FML RDH MTC JLM VCC-1 RIFC |

3 3 3 3 3 3 |

| El Gran Cordero | MGMC ATC |

5 5 |

Productoras La Veta | MACM GRV |

5 4 |

| Las Trece Estrellas | MLRC JCM |

8 4 |

Organización Borrecos | ISG MLR |

4 4 |

| El Manantial del Potro | MGGM VCC MCM RGC |

5 5 5 5 |

* Sheep producers.

In relation to this, a higher connection speaks of the ability of the actor in question to influence, therefore, in a certain degree of negotiation and legitimation the other members of his group, but it also points to a certain susceptibility of being influenced by the other members. In this case, the actors that are better linked are the ones presented in Table 2.

Thus, the higher number of actors with a similar nodal degree there is a broader and more diverse connection in terms of distribution of inputs inside the group. On the contrary, the presence of nodes with a radically higher nodal degree than the rest generates nodes with the possibility of centralizing and monopolizing information and, therefore, of distributing it according to their personal criteria, as is the case of Las Trece Estrellas ( ), Ganaderas Comprometidas (

), Ganaderas Comprometidas ( ), Región Palmeña (

), Región Palmeña ( ), La Estrella de Salitrillo (

), La Estrella de Salitrillo ( ), or Productoras de ovinos La Veta (

), or Productoras de ovinos La Veta ( ).

).

On the other hand, organizations were observed made up of differentiated flows of information; although an important percentage of the women interviewed said they recognized the mission (49o%), objectives (59 %) and regulations (75 %) of the organization to which they belong, important differences are seen between groups, which are related to schooling and an incipient organizational culture, considering the short time that they have been working as a group, as well as the difficulty in applying concepts that are not of common use to them. On the other hand, the nodal frequency of each member indicates, indirectly, that there is the possibility of diverse ways to communicate without depending on a “central” actor (as is the case of El Santuario del Nazareno ( ). Examples of this are the cases of El Manantial del Potro (

). Examples of this are the cases of El Manantial del Potro ( ), Ovinocultoras de Sn. José Punteros (

), Ovinocultoras de Sn. José Punteros ( ) and El Gran Cordero (

) and El Gran Cordero ( ).

).

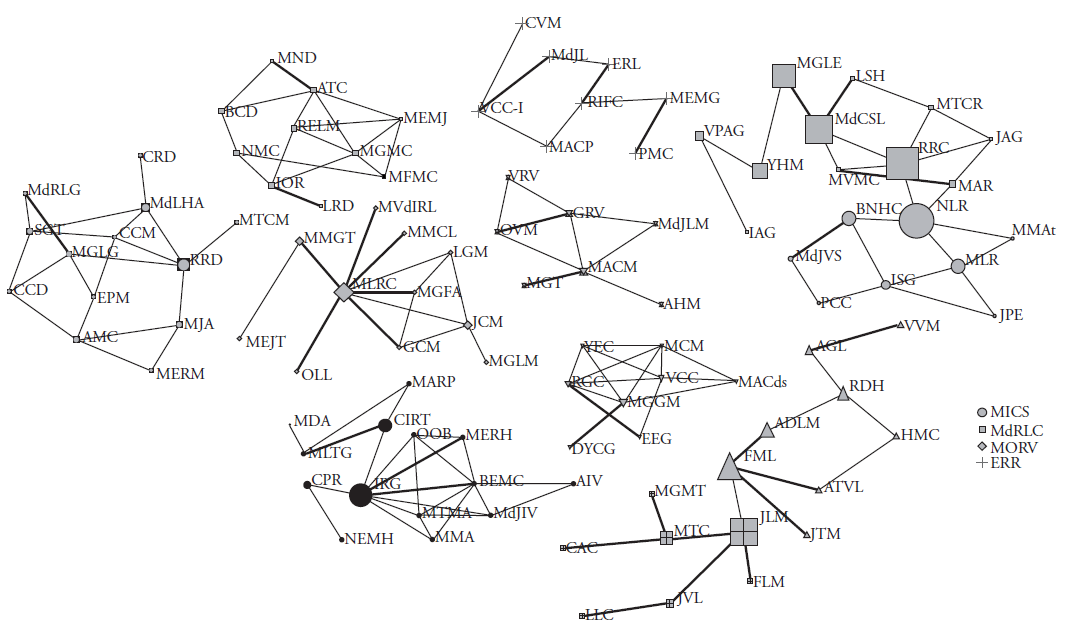

Degree of Intermediation (Betweenness) in 11 RPS for sheep production

When assuming that in every social structure all of the actors are linked in one way or another, it is not adventurous to presume that between each pair of actors there are mediators who facilitate or hinder the flow of correlation between those actors, managing to determine their degree of isolation or communication with the groups or individuals in the communities. Fortunately, the diversity of social links opens the possibility of exploring alternate paths, without having to forcibly go through the same actor; therefore, the higher number of alternatives (intermediaries) that a node has to make its message reach, the less dependent it will be. This allows locating those actors that not only connect different groups but which may, at a given moment, generate and facilitate processes of negotiation and communication between distant or isolated sectors. According to this, for each of the groups analyzed (Figure 4), differentiated degrees of intermediation are observed, as well as those participants who, in the exchange of information with their peers, become bridge nodes. It should be pointed out that the presence of a higher number of subjects with similar degrees of intermediation speaks of a more communicated group, so that a lower number of important degrees of intermediation will be an indication of a network where one or two actors control the flow of information between the subjects. Within the organizations analyzed, an example of the first would be: Ovinocultoras de Sn José Punteros ( ), Derivados el Santuario del Nazareno and El Manantial del Potro.

), Derivados el Santuario del Nazareno and El Manantial del Potro.

Source: authors’ elaboration.

Figure 4 Most outstanding Degrees of Intermediation (Betweenness) in the RPS.

For the second case, the following could be mentioned: 13 Estrellas ( ), Región Palmeña (

), Región Palmeña ( ), La Estrella de Salitrillo (

), La Estrella de Salitrillo ( ), and Diez Corazones (

), and Diez Corazones ( ).

).

The participants with the most significant Betweenness degrees are those that have the trust of their partners for the exchange of information regarding themes related to their community, economy, work, and of personal nature, but they are also nodes that allow linking actors and groups. This permits locating those women who have more social weight among the other participants; therefore, those with whom it is more feasible to carry out processes of diffusion or negotiation inside each of the groups analyzed (Table 3).

Table 3 Most outstanding Degrees of Intermediation (Betweenness) in the RPS.

| SPR | Actor | Intermedia | SPR | Actor | Intermedia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Derivados Santuario del Nazareno |

BEMC MLTG CIRT MTMA MGLG RRD EPM AMC MdLHA MGMC ATC MFMC LGM GCM |

5 4 3 3 49 40 25 18 15 12 11 5 1 1 |

Ganaderas Comprometidas |

RRC MVMC MDCSL BNHC ISG FML ATVL ADLM JLM MTC JVL VCC MdJL MEMG |

18 14 12 4 4 7 3 2 3 2 2 2 1 1 |

| Organización Agronómica | |||||

| Ovinocultoras de San José Punteros | Borrecos | ||||

| 10 Corazones | |||||

| El Gran Cordero | La Estrella de Salitrillo | ||||

| Las Trece Estrellas | Región Palmeña | ||||

| El Manantial del Potro | VCC RGC MGGM |

15 14 12 |

Productoras de ovinos La Veta | MACM GRV |

13 11 |

When there are actors who not only connect to other actors of the same group but also to those in others (Figure 5), as is the case of the relationship between Organización agronómica Borrecos-Ganaderas Comprometidas and 10 Corazones-La Estrella de Salitrillo, the possibility for the integration of broader groups is opened; therefore, the possibility presents itself of building a social network with the other groups of the project, which appear disconnected one from another. In this sense, the benefits of network work are multiple, since cooperation allows facing complex problems that would be impossible to address with a single actor.

Source: authors’ elaboration.

Figure 5 Bridge actors, with significant degrees of Betweenness, among 4 RPS.

Although at the time of the study a social network made up by all the participants cannot be observed but rather, in appearance, closed groups, contacts between groups can be distinguished through actors who acted as bridge nodes between one and another group. This points to relationships of friendship and communication that go beyond the organized group and which allow thinking about the possibility of a broader social network; in this sense, Diez (2008) points out that through the space of networks the various organizations communicate and share resources and abilities, building spaces of work in common that allow the development of projects and innovations. The presence of an active network assumes the existence of communicable contents between the parts involved, in the sense of availability of data and information and mechanisms for interpretation.

Even though the network between organizations in this study is incipient, there are indications of participation in other formal and informal organizational ways; 32 % of the women interviewed manifested collaborating with other types of local organizations. This indicates certain experience of group work, as well as the perception of group work generating opportunities to perform actions in favor of the community. Weinberg and Jütting (2001) point out that participation in other groups increases the probability of participating in the local development of the groups. In addition, the members of informal groups and networks probably have access to greater information; therefore, they can make a better judgment about the costs and benefits of participating in a group.

In turn, Cardona and López (2001) point out that the groups weave relationships that are potentialities for the strengthening of actions; these do not take place spontaneously, correspond to a past built from the conditions of development of organizations and the social characteristics of the place. In this regard, the interview respondents perceive safety and trust in their neighbors (43 %) when they point out that there is a high probability of the neighbors being aware of their home in their absence and 52 % indicated that they help each other between neighbors; on the other hand, it should be highlighted that 27 % of the women indicated low collaboration in their community to solve a problem and that the division of the community obeys primarily political issues, 23o%; inequality of resources, 22 %; and from receiving some government program backing, 21 %.

With the analysis of the points treated, valuable information is obtained to identify elements that need to be considered in possible interventions, in the interest of contributing to the development of these groups and their communities.

Conclusions

The application of the SNA allowed identifying each organization of women sheep producers in function of their inner management of bonds of trust and communication. It was observed that there is no social network in general, although there are small networks of trust inside the groups that imply certain communication between members and the presence of references around themes related to their communities, family economies, work and of personal nature, but also of followers, people isolated and nodes that connect participants, as well as to the groups. This facilitates the establishment of working strategies with the groups, with the aim of seeking a broader correlation, not only between participants, but also between all the organizations of the project.

The results obtained show the need to reinforce the concepts of cooperation and management of information in the groups, as well as the process through which the strategy of rural development proposed is being transmitted, with the purpose of allowing the members to have the certainty about what they want to do, where they want to go, and which are the rules of the game that should be followed to attain their objectives.

Literatura Citada

Anheir, Helmut, and Jeremy Kendall. 2002. Interpersonal Trust and Voluntary associations: examining three approaches. British Journal of Sociology. Vol. 53. No. 3. [ Links ]

Berdegué Julio. 2002. Cooperando para competir. Factores de Éxito de las Empresas Asociativas Campesinas. RIMISP. Enero. [ Links ]

Bourdieu Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In: J. Richardson (ed) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood). Publicado en linea: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm (20/04/2016). [ Links ]

Brugué, Quim, Ricard Gomá, y Joan Subirats. 2002. Introducción. In: Subirats Joan (coord). Redes, territorios y gobierno. Nuevas respuestas locales a los retos de la globalización. España. pp: 5-18. [ Links ]

Buciega, Almudena, y Javier Esparcia. 2013. Desarrollo, Territorio y Capital Social. Un análisis a partir de dinámicas relacionales en el desarrollo rural. Redes-Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales, 24(1) 176-192. [ Links ]

Cardona Marleny, y María Victoria López. 2001. La capacidad organizativa de las redes y las cadenas en la dinámica económica social. Revista Universidad Eafit. Abril-junio no. 122. Medellín Colombia. pp: 9-21. [ Links ]

Castaños Carlos. 1987. Organización campesina. La estrategia truncada. Ed. Agro comunicación Sáenz Colín y Asociados. México. 447 p. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel. 2001. La era de la información. Vol. 1, La Sociedad en Red. Alianza Ed., Madrid, 1a reimpresión. [ Links ]

Chiriboga Manuel. 2003. Innovación, conocimiento y desarrollo rural. Revista Debate Agrario. No. 26: 119-149. [ Links ]

Choucri, Nazli. 2001. Red de conocimientos para un salto tecnológico. Revista Cooperación Sur, PNUD-CTPD. No. 2. [ Links ]

CP (Colegio de Postgraduados). 2010. Programa de Reconversión productiva de frijol en el altiplano potosino-zacatecano. Informe. 20 p. [ Links ]

Coleman, James. 1990. Social capital, foundations of Social Theory. En Coleman, James (comp), Cambridge, Massachusets. The Belknap Press of Harward University Press. [ Links ]

Contreras Rodrigo. 2005. Empoderamiento campesino y desarrollo rural. Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales. No. 04: 55-68. [ Links ]

Cuchillo, Paulo. 2010. La cohesión social para el desarrollo. Comunicaciones, comunicación y medios. In: In: http://comunicaziones.blogspot.com/2010/03/la-cohesion-social-para-el-desarrollo.html consultado el 18 de agosto de 2010. [ Links ]

Cuellar, Roberto. 2009. Cohesión social y democracia. Instituto Internacional para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral 2010. In: http://www.idea.int/resources/analysis/upload]/Es_Cuellar_low_2.pdf (05/07/2010). [ Links ]

Diez, José Ignacio. 2008. Organizaciones, Redes, Innovación y Competitividad Territorial: Análisis del Caso Bahía Blanca. Redes. Revista Hispana para el Análisis de Redes Sociales. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Junio. No. 014. [ Links ]

Durston, John. 2003. Capital social. Parte del problema, parte de la solución, su papel en la persistencia y en la superación de la pobreza en América Latina y el Caribe. In: Atria, Raul Siles, Marcelo, Arriagada, Irma, Robinson L. Lindo; Whiteford Scout (comp). Capital social y reducción de la pobreza en América Latina y el Caribe: En busca de un nuevo paradigma. CEPAL. pp: 147-203. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 1994. Participación campesina para una agricultura sostenible en países de América Latina. Serie Participación Popular. Publicado en http://www.fao.org/newsroom/es/field/2005/index.html (22022011). [ Links ]

Flores, Margarita, y Fernando Rello. 2001. Capital social: Virtudes y limitaciones, Ponencia presentada en la Conferencia Regional sobre Capital Social y Pobreza. CEPAL y Universidad del Estado de Michigan, Santiago de Chile, 24-26 de septiembre de 2001. Recuperado de http://www.cepal.org/prensa/noticias/comunicados/3/7903/flores-rello.pdf. [ Links ]

Flores, Margarita , y Fernando Rello. 2002. Capital social rural. Experiencias de México y Centroamérica. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, Plaza y Valdés S. A. de C. V. 1ra. ed. México. 195 p. [ Links ]

Freeman, Linton. 1979. Centrality in networks: I. Conceptual clarification. Social Networks 1: 215-239. Recuperado de http://leonidzhukov.net/hse/2014/socialnetworks/papers/freeman79-centrality.pdf (12/10/2016). [ Links ]

Gayen, K., and R. Raeside. 2010. Social Networks and contraception practice of women in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine. 71. pp: 1584-1592. [ Links ]

González de la Fuente, Iñigo. 2012. Socialización comunitaria y procesos educativos informales en el México rural. Estudio de caso Gazeta de Antropología, 28(1), artículo 16 http://hdl.handle.net/10481/21530. [ Links ]

Gordon, Sara. 2005. Confianza, capital social y desempeño de organizaciones. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, enero-marzo. No. 193. vol. 47. http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/src/inicio/HomRevRed.jsp?iCveEntRev=421 (25/07/2011). [ Links ]

Helly, Denisse. 2002. Cohesión social, democracia, participación social y lazo societal. El caso de las minorías étnicas y nacionales en Canadá. INRS - Urbanisation, Culture etSociété. http://e-spacio.uned.es:8080/fedora/get/bibliuned:filopoli-2002-20-0001/pdf (29/072011). [ Links ]

Hopenhayn, Martin. 2007. Cohesión social: un puente entre inclusión social y sentido de pertenencia. In: http://www.google.com.mx/search?hl=es&q=inter%c3%Aqs+personal+%2&cohesi%c3%B3n+social%29&aq=f& (2/06/2010). [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 2007. Censo Agrícola, Ganadero y Forestal 2007. [ Links ]

Landazábal Cuervo, Diana Patricia, Yeison Albero Olarte Ramírez, Víctor Hugo Cabrera Vargas, y D. Carolina Verano Vergel. 2009. Análisis de redes sociales y del éxito en un grupo de estudiantes de bachillerato a distancia. Revista Investigaciones UNAD. Vol. 8, no. 1. [ Links ]

Longo, María Eugenia, y María Cecilia Cejas. 2003. Límites del concepto de capital social comentarios sobre el seminario Capital social y programas de superación de la pobreza: lineamientos para la acción. Santiago de Chile. 2003. In: http://www.eclac.cl.dds/noticias/noticias3/13523/Longo_Cejas_200311.pdf (25/05/2010). [ Links ]

Molina, José Luis, Agueda Quiroga, Isidro Maya Jariego, y Ainhoa Federico De la Rúa. 2006. Taller de autoformación en programas informáticos de análisis de redes sociales. Col. Documents. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Bacelona. España. 127 p. [ Links ]

Molina, José Luis , y Alba Alayo. 2005. Reciprocidad hoy: la red de las unidades domésticas y servicios públicos en dos colectivos en Porras, José I.; Espinoza, Vicente. Redes: Enfoques y aplicaciones del Análisis de Redes Sociales (ARS). Ed Universidad Bolivariana, Chile. 440 p. [ Links ]

Navarro Sánchez, Luis, y Juan Pablo Salazar Fernández. 2007. Análisis de redes sociales aplicado a redes de investigación en ciencia y tecnología. Síntesis tecnológica. Vol. 3. No. 2. pp: 69-86. [ Links ]

Nuñez Espinoza, Juan Felipe. 2008. Exploración en la operación y modelización de Redes Sociales de Comunicación para el desarrollo rural en zonas marginadas de Latinoamérica. Estudios de casos: Red Nacional de Desarrollo Rural Sustentable (RENDRUS) y Red Iniciativa de Nutrición Humana. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña, Cátedra UNESCO en Sostenibilidad. Barcelona, España. [ Links ]

Perea Peña, Mauricio, Angélica Espinoza Ortega, Ernesto Sánchez Vera, and E. Ernesto Bobadilla Soto. 2014. Gender and social capital in technological innovation in smallholder systems of sheep production in the state of Michoacán, México. African Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development ISSN 2375-0693 Vol. 2(5), pp: 147-154. [ Links ]

Porras, José, y Vicente Espinoza. 2005. Redes: enfoques y aplicaciones del Análisis de Redes Sociales (ARS). Universidad Bolivariana, Chile. [ Links ]

PNUD (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo). 2001. Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano. Poner el adelanto tecnológico al servicio del desarrollo humano. Mundi-Prensa. México. [ Links ]

Requena Santos, Félix. 2004. El Capital Social en la Encuesta de Calidad de Vida en el Trabajo. Revista Papers 73. pp: 11-26. [ Links ]

Robertson, Roland. 2003. Glocalización: tiempo-espacio y homogeneidad-heterogeneidad In Cansancio del Leviatán: problemas políticos de la mundialización. (comp) Monedero Fernández. Juan Carlos. Madrid: Trotta. pp: 261-284. [ Links ]

Santos, María. 2015. Training networks for adapting to the agricultural system: latino blueberry farmers in the United States. Int. J. Agr. Ext. 03 (01). pp: 13-23. [ Links ]

Torres, Federico. 2000. Uso Productivo de las Remesas en México, Centroamérica y República Dominicana. Publicado en línea. In: http://www.eclac.cl/celade/proyectos/migracion/Torres.doc (19/11/2013). [ Links ]

Verd Perci, Joan Manuel, y Joel Martí Olive. 1999. Muestreo y recogida de datos en el análisis de redes sociales. QUESTII´O Vol. 23, 3. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. [ Links ]

Vivero, José. 2007. Hacia una cohesión social sin hambre en América Latina. La crónica de hoy. (7 de julio). In: http://www.rlc.fao.org/iniciativa/pdf/cronica.pfd?id_nota=310728 (05/07/2010). [ Links ]

Wasserman, Stanley, and Khaterine Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis, Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Weinberger, Katinka, and Paul Jütting Johannes. 2001. Women´s participation in local organizations: Conditions and Constraints. World Development Vol. 29. No. 8. pp: 1391-1404. [ Links ]

White, Douglas, Michael Shneegg, Lilyan Brudned, and Hugo Nutini. 2000. Conectividad múltiple, frontera e integración: Parentesco y compadrazgo en Tlaxcala rural. In: Gil Mendieta, Jorge Gil, Samuel Schmidt. Análisis de redes: Aplicaciones en ciencias sociales. Ed. UNAM-IMASS. Mexico. 2000. p. 42. [ Links ]

Received: January 2014; Accepted: November 2016

texto en

texto en