Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.13 no.3 Texcoco jul./sep. 2016

Articles

Children's savings, an approach to financial inclusion: Chispitas from the Fundación Ayú, Oaxaca, México

1 Desarrollo Rural. Colegio de Postgraduados, Carretera Federal México-Texcoco Km. 36.5, Montecillo Estado de México. 56230. (garcos@colpos.mx) (ohr@colpos.mx) (emmazm@yahoo.com.mx)

Microfinances have placed an emphasis on microcredits, leaving aside other elements of financial services such as savings in poor families, and virtually ignoring the presence and participation of girls and boys in schemes such as the savings funds. The article analyzes the operation of two savings funds as part of the strategy used to combat poverty, by Fundación Ayú, in the Mixtec Region of Oaxaca, which allows, promotes and stimulates children's savings, contributing to the financial inclusion of boys, girls and teenagers. The study was carried out in the municipality of San Francisco Jaltepetongo, Oaxaca. The methodology used was based on the application of a questionnaire, interviews and a financial education workshop. Results indicate that the presence and example of mothers in the savings funds are the principal influence for boys and girls to save; also, empirically, they distinguish between desires and needs, a basis for future financial education, so their savings have specific objectives that they decide for themselves. The conclusion is that boys and girls begin to relate with terms such as loan, interest, money management, which brings them closer to being financially included, outside formal banking.

Key words: savings; savings funds; Mixtec región; loans

Las microfinanzas han puesto énfasis en los microcréditos, dejando de lado otros elementos de los servicios financieros como el ahorro en las familias pobres, y prácticamente ignorando la presencia y participación de niñas y niños en esquemas como las cajas de ahorro. En el artículo se analiza la operación de dos cajas de ahorro como parte de la estrategia de combate a la pobreza de la Fundación Ayú en la Mixteca Oaxaqueña, que permite, fomenta y estimula el ahorro infantil, contribuyendo a la inclusión financiera de niños, niñas y adolescentes. La investigación se realizó en el municipio de San Francisco Jaltepetongo, Oaxaca. La metodología utilizada se basó en la aplicación de un cuestionario, entrevistas y un taller de educación financiera. Los resultados indican que la presencia y el ejemplo de las madres en las cajas son la principal influencia para que niños y niñas ahorren; además, de manera empírica, distinguen entre deseos y necesidades, base para una futura educación financiera, por lo que sus ahorros tienen objetivos específicos que ellos mismos deciden. La conclusión es que niños y niñas comienzan a relacionarse con términos como préstamo, interés, manejo de dinero, lo que los aproxima a ser incluidos financieramente, fuera de la banca formal.

Palabras clave: ahorro; cajas de ahorro; mixteca; préstamos

Introduction

In México, the organization that regulates the operation of the entities that comprise the financial system, the National Banking and Values Commission (Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores, CNBV, 2015), specifies that financial inclusion means "access and use of a range of financial products and services by the population, under an appropriate regulation that oversees the interests of the system's users and promotes their financial capacities". The National Council for Financial Inclusion (Consejo Nacional de Inclusión Financiera, CNIF, 2013) states that financial inclusion (FI) considers four primordial dimensions: i) access, referring to the financial infrastructure available to offer financial services and products, such as branch offices, ATMs, sales points terminals, among others; ii) use, related to the number of financial products available that are accessible for users, such as savings, checks, payroll accounts, deposits, credit cards, variety of credits and insurance, primarily; iii) financial education, which addresses knowledge of financial services and products, and their responsible use; and, finally, iv) consumer protection, through the creation of situations of equity between users and providers of financial services. However, all these elements do not satisfy fully the needs of the general population, situation that is exacerbated specifically when the issue at hand is rural communities under conditions of poverty and marginalization. Examples of this are the figures for the state of Oaxaca, which has 1.34 branch offices for every 10 000 inhabitants, compared to a national average of 4.76. In addition, in 417 of its 570 municipalities, there is not a single banking access channel, whether through branch offices or correspondents.

Campos (2005) confirms it in his study, where he details that a person of low income who resides in the north of the country, in populations of over 500 000 inhabitants, has a probability of using banks twice higher than if he/she lives in a small city or in a rural community. In the south of the country, the probabilities of having a bank account would be even lower or practically null. The level of income has a direct relationship with participation in the financial system, given that the commercial bank is directed at potential clients of medium and high income, which is why the poor remain at a disadvantage (Rutherford, 2002). In addition, Mansell (1995), mentions that the centrality of the financial infrastructure of the country must be considered.

Therefore, Esquivel (2008) says that more than half of the Mexican families, 57 %, are outside the margin of financial services, primarily because of the lack of adaptation of the products and services offered to them. The prior idea is crystallized with the opinion of Heimann et al. (2009) when they state that: "as the products and services offered are adapted to the needs of the population their level of use will be favored, contributing to a higher efficiency and profitability of the financial intermediaries that offer them".

The Center for Financial Inclusion at International ACCION (Centro para la Inclusión Financiera en ACCION International, 2009) argues that the importance of people being accepted financially lies in that FI has the potential of contributing to the family economy with an effect on the country's economy, as well as reducing social inequality. An aspect of greater impact is that financial services, when used properly, can have an influence in improving the quality of life and productivity of the micro-enterprises of the low-income households that have access to these services.

The data obtained by De la Madrid in the Report on Discrimination in México 2012, in the subject of credit, show that the Mexican financial system excludes many people for many reasons, although the main one is social class, whether for reasons of income or of identity. The principal barriers and causes of discrimination are informality, the inability to demonstrate income, and the situation of irregularity of properties or assets that could be offered as guarantee, in addition to an insufficient financial culture. By segment of the population, women specifically, particularly the poor and who reside in rural areas, were marginalized by this condition. Recently, women have begun to be valued by the financial system, because they are considered to be more responsible and prompt in paying, so they have become the favorite market niche of microcredits. Another segment that has been relegated is that of youth and adults, the latter because of the difficulty to demonstrate income and offer collateral; almost all bank institutions refuse to lend resources to people over 60 years. For the case of young people, they are also affected because they generally perform informal jobs, which, in addition, have low pay; boys, girls and teenagers are considered an object of attention only by some banks and almost exclusively in urban zones. De la Madrid (2012) sums up this situation with a reflection: "A financial system that is not capable of finding financing mechanisms for younger populations, that is, which cannot take risks in favor of this sector of the community, will tend to have an elderly population that never managed to save, develop or have sufficient economic backing for retirement. In contrast, the societies that have understood how to accompany their younger populations in the economic takeoff of their lives are those that today are found among the most developed in the world". Other segments of the population excluded from the financial system are people that belong to indigenous communities and people with disabilities.

This article analyzes how microfinances, through the operation of two savings funds, can become an important element for the promotion and creation of the habit of saving in boys and girls, allowing their financial inclusion in the future, through three variables: who teaches them to save, how they perceive the difference between wishes and needs, and how their participation in savings funds makes them visible to their community. The hypothesis assumed in the study is that it is the mothers who exert the greatest influence in the formation of the habit of saving, with implications in their financial education and inclusion.

Theoretical approach: saving for accumulation of assets under conditions of uncertainty, the educational process and financial education

Taking as starting point the question of how to get out of poverty, without a doubt a possible response is through savings and the accumulation of assets, whether they are human, physical, financial or social (Sherraden et al., 2001). Analyzing the importance of the accumulation of physical and financial assets by poor families includes three important elements; first, because having this type of assets allows participating in a market economy; second, because unequal distribution and asymmetrical access to these assets can contribute to reproducing the condition of poverty; and, third, because the families that have this kind of assets see their wellbeing, economic security, and even their behavior, changed (Bernal, 2007).

Poor people have several savings strategies, as pointed out by Castillo (2012) in Daryl Collins, Portfolios of the Poor, by highlighting three outstanding discoveries. 1) The poor are the most important actors to decrease poverty; they make daily efforts to help themselves in an active way. External actors support these processes, but they are not defining in this struggle. 2) The poor use financial tools in an active manner, not in spite of being poor, but rather precisely because they are poor; they have designed and found alternatives to manage their scarce money. In their research, the authors found that they use an average of 10 different financial instruments per year, diversification that responds to different needs and opportunities. 3) The poor "manage" money by saving when they can and asking for loans when necessary. The authors arrive at a key conclusion: the demand for a place for savings is infinitely higher than the demand for obtaining credit.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2013) reports that the poor have several ways of saving. The first is in species; normally they do it by storing food cereals, such as maize or rice, or in livestock, such as cows, pigs, goats or hens, and, occasionally, in articles such as jewels, gold or other goods, whose value increases and allows them to be sold easily in the future to obtain money. The second way is saving money, whether at home or in an institution, since almost all people, included the very poor, have the need to manage money for their daily life. The main advantages of this type of savings are that it is easy to carry out, store, scarcely visible, and has the advantage of being fungible; that is, it can be used for many purposes.

A third type of saving is giving something; people make gifts or offer services not only out of generosity, but also sometimes with the hope of the favor being returned when needed. An example of this type of saving is the tequio, traditional in many rural regions.

In the words of Bazán and Saraví (2012), popular finances include a large amount of small, broad and heterogeneous acts carried out by the households of low income with the aim of facing the daily subsistence, improving the family's welfare, or responding to needs and unforeseen risks that grow due to the vulnerability of their income. Within the strategies developed, they include work by boys and girls, formal employment, self-employment, micro-enterprises, and, therefore, different ways of saving, such as those exposed before.

Assuming that boys, girls and young people are social and economic actors in the present and in the future, whose decisions will influence the development of their societies, it turns out to be important to understand how it is that boys, girls and teenagers learn to save. In this regard, taking up Piaget, Amar et al. (2003) mention that from the constructivist perspective, it is held that girl and boys are active individuals who build on their own both their understandings and the way in which they are organized. In this process of representation construction, the social environment acts like the supplier of experiences and contributes the contents that will characterize the representation, although the way in which the subject organizes these elements will be mediated by the level of development of their cognitive structures.

Therefore, Delval (1989) suggests some of the relevant components that make up the representations that boys, girls and teenagers make regarding reality. These are identified in four aspects: rules, values, information and explications. The first three are influenced to a great degree by the parents and the family itself, while the issue of explanations regarding the cause of things is almost absent from the social transmission, and boys and girls are forced to build them with the intellectual tools that they have available to them.

These social actors begin to relate to the economic reality since their first years of life, from such everyday experiences as going to the store, to the market, or listening to their parents and other adults speak about "the economic scope" or about the price of the products they purchase at shops. This forces them to make a constant effort to build for themselves explicative models of this reality, which is so close yet at the same time so complex and difficult to approach.

The educational process

The transmission of culture that adult generations carry out towards young people is what is called education (Delval, 1983). Since birth, and even before, boys and girls are subjected to influence from the society that they live in. Through this social pressure, they become constituted into members of it, acquiring the guidelines for behavior that are characteristic of it, and they will learn to behave as adults in that society, with their language and the whole of culture.

The educational process is performed in multiple ways, in the family, in the street, and in school. Through contact with other individuals and with the surrounding world, they become imbued with social influence. Through it characteristics are acquired that are common to all, men and women, in all times; those that are considered human and other more specific ones that can be characteristic of a nation, of a city, of a social class, of a small group, or of a family. However, in any case, this transmission has a mission to conserve the existing order, since the adults tend to reproduce themselves in the children, not just in the biological sense but also in the cultural one.

The broad growth in the offer of financial services, formal and informal, is generating a strong imbalance between suppliers and users, derived from the low financial education of the latter. Currently, Carbajal (2008) mentions that within the reality of the poor, where imbalances of information constitute the norm, the development that the financial market has experienced is leading them to understand increasingly less the new options available to them and, therefore, it is likely that they do not use them to their benefit or, worse still, that they distance them from the formal system.

The OECD (2005) defines financial education as "the process by which financial consumers and investors improve their understanding of financial products and concepts through information, instruction or objective advise, develop abilities and confidence to comprehend better the financial risks and opportunities, make informed decisions, know when to obtain help and make other effective decisions that allow them to improve their financial condition".

Coates (2009) has highlighted that in the length of a person's existence, "didactic situations" take place, where they are more receptive to financial education; for example, during childhood, in the university or marriage stage, so it becomes necessary to begin the financial literacy in the first stages of life, since there are increasingly more financial products, they are more varied, complex and sophisticated, which is why it is necessary for parents to instill the habit of saving, so that when they reach the adult age they can see it as something natural. Therefore, financial education will allow boys, girls and teenagers to acquire the habit of saving and to better understand the options offered by suppliers of financial services.

Methodology

Study region

The state of Oaxaca represents 4.8 % of the total national surface, occupying the fifth place in the country; it is made up of 570 municipalities, almost three fourths of the total of municipalities in the whole Mexican republic. It is the state with the greatest ethnic and linguistic diversity in México. In the current territory of Oaxaca, there are 18 ethnic groups of the 65 in the country: Mixteco, Zapoteco, Triqui, Mixe, Chatino, Chinanteco, Huave, Mazateco, Amuzgo, Nahua, Zoque, Chontal of Oaxaca, Cuicateco, Ixcateco, Chocholteco, Tacuate, Afro-mestizo of the Costa Chica and to a lesser degree Tzotzil, which together are more than a million inhabitants, around 34.2 % of the state total, distributed in 2563 localities (official webpage of the state of Oaxaca, 2010-2016 administration).

In one of the municipalities of the state of Oaxaca, Fundación Ayú was formed, which since its origin has sought to integrate resources and efforts to combat poverty in the Mixtec Region, one of the eight regions of the state, located north of Oaxaca.

The Mixtec Region in Oaxaca adjoins the states of Puebla and Guerrero, with the region of Cañada to the east; with Valles Centrales to the southeast; and with Sierra Sur, to the south. In Oaxaca, the Mixtec Region occupies 189 municipalities of the 14 districts.

The National Population Council (Consejo Nacional de Población, Conapo, 2010), reports that Oaxaca occupies the third place nationwide, classified with a very high level of marginalization. The municipality where the study was performed, San Francisco Jaltepetongo, is located in a medium level of marginalization, with a total of 1110 inhabitants, according to the Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information (Instituto de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, INEGI, 2012).

Since more than 15 years ago, Fundación Ayú has promoted the integration of savings funds in the communities, since within the strategy of rural development and poverty combat that it implemented, the funds were the axis around which it revolved, and rural women were the ones in charge of training, administration and operation in them.

However, the objective of the banks is not only savings and loans, but rather they go beyond this for they also have the instruction of promoting saving among boys and girls. Therefore, savings funds were created for them that are called Los Chispitas. Boys, girls and teenagers can participate in them, since the moment they are born, represented by their parents, but with accounts and savings cards in their name, and up to 15 years old, age at which if they decide to continue saving they are incorporated into the adult funds.

Los Chispitas have a similar scheme to that of the adult savings funds. They have a committee made up of the members of the accounts; they gather every fortnight together with the adults. The mothers or fathers of the committee's children support them to manage the funds, collect the participants' savings, record the resources delivered in the savings bank books and, in time, every six months, carry out the operation balance of the children's funds. Every fortnight the amount of resources that entered the children's funds is counted, and this money can be used to loan it to adults, paying the children the interest that the money generated. The boys and girls do not have access to loans on their own; only their parents, members of the funds, can have access to them.

A questionnaire was applied for the research, and a participative workshop was carried out with boys and girls, as well as semi-structured interviews with key informants, like the designer of the savings funds, the promoter who was responsible for the funds in their origin, and the women members from the municipality's funds committees, one with central offices in the municipal township, San Francisco Jaltepetongo, and another in the locality of San Isidro. The children presidents and secretaries of the funds were asked for the lists of members of both of them, and, together with the mothers who support the committees, the age of each member was identified. From a universe of 61 members, the questionnaire was applied to 42 boys and girls from both localities, in addition to eight semi-structured interviews with adults. The members of the funds gather on days 15 and 30 of every month, so in order to apply the questionnaire we attended these meetings from 2013 to July 2014.

Documents were reviewed, such as the lists of members, individual savings bank books, the fund's savings books, as well as the formats of biannual balances.

Results from the "Chispitas" boys and girls studied

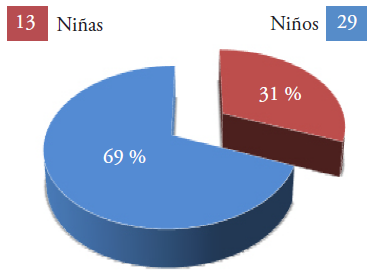

In the municipality of San Francisco Jaltepetongo, Oaxaca, and its locality of San Isidro, the two Chispitas savings funds are located, with a total of 61 members, 41 boys and 20 girls. In San Francisco there are 23 members and in San Isidro, 38 (Figure 1).

Interviews were performed with 42 members who accepted to participate in the field work, 13 girls and 29 boys, 21 in each locality, and a participative workshop was carried out on financial education with the attendance of 18 Chispitas and seven adults.

The socioeconomic information obtained from those interviewed reflects that the average age is ten years in girls and 11 years in boys; the maximum age for both is 15 years, and the minimum five for girls and eight for boys. The level of schooling is located in a very broad range, since those who participate include those who attend kinder garden to those who are in third year of secondary, that is, who have nine years of schooling. The fact stands out that, in general, the number of boys who save is higher than those of girls who save, and their level of schooling, which is in relation to age also. Some mothers pointed out that the girls are more timid and many are not interested in participating in the savings funds. They also do not occupy directing positions in the children's funds, or as president or secretary.

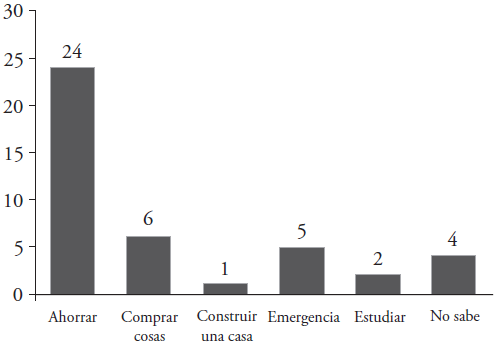

The socioeconomic profile of the families of the Chispitas boys and girls corresponds to households where the parent is devoted, in majority, to the field (52 %), followed by those devoted to pyrotechnics (fireworks manufacture), particularly in San Francisco, Jaltepetongo (33 %), while the rest (14 %) has some trade or offers a service such as chauffeuring (Figure 2).

Source: field work carried out in 2013-2014.

Figure 2 Occupation of parents of the Chispitas members.

The participation of boys and girls in savings funds involves them directly with the Fundación Ayú and with the community that they belong to. For this reason, they were asked about what being Chispitas represented to them and, even when most don't know (24), there were interesting responses, such as learning to save (12), that it is a pride (4), and even, that it is a way to get together with friends (2).

Regarding the activities of mothers of Chispitas members, 38 % are house wives, while 21 % are devoted to the household and field tasks, and an equal percentage adds the elaboration and sale of wheat tortillas to their work in the household, particularly in the locality of San Isidro Jaltepetongo; some women also collaborate in the manufacture and sales of pyrotechnics (10 %). The least percentage corresponds to some various trades and only in one case there is a professional (nurse).

For the theme being analyzed, it was important to consider the work of women; Bazán and Saraví (2012) indicate that it is characterized by being rather unstable, associated to the development of family trajectories, quite limited in the rural sector because the periods when some activities are available, for which they can receive income, are irregular and have much volatility from the income received.

Boys and girls have three to seven years as savers. Those interviewed can be compared to the 1 % of the children who report having a savings account, according to data from the first survey on financial culture in México BANAMEX-UNAM (2008).

In rural and poor families, it is frequent for girls and boys to collaborate in some tasks that help with family income. Of the Chispitas members interviewed, 24 % collaborate in tasks with the family, primarily in the field, in the sale of some products, in the elaboration of fireworks, and even, in brick-laying jobs.

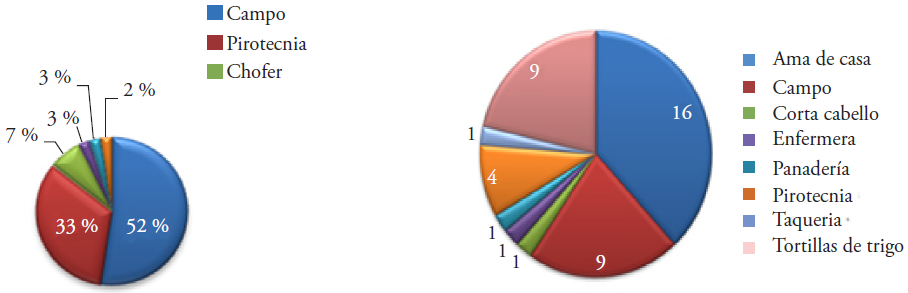

Concerning the reasons why boys and girls have money to save in the children's savings funds, one of the responses more frequently given was setting apart to have money in the future, followed by for the purpose of buying things, although there were also others, such as those who destine it to emergencies; likewise, some don't know what it is used for, since one of the parents manages it. The answers are shown in Figure 3 Nehemías' testimony completes the idea.

My name is Nehemías Noé and I live in the town of Yucano; I walk for one hour to come to the meeting of the children's savings fund. I am 10 years old and I study the fifth grade. Every fortnight I save 20 pesos that my mother gives me. My father taught me to save. I am saving because I want to buy myself shoes, school supplies, to pay debts and to help my family to buy fruits and some chickens. I think it is important to save because that way we can take out loans (Chispitas member from the San Isidro bank).

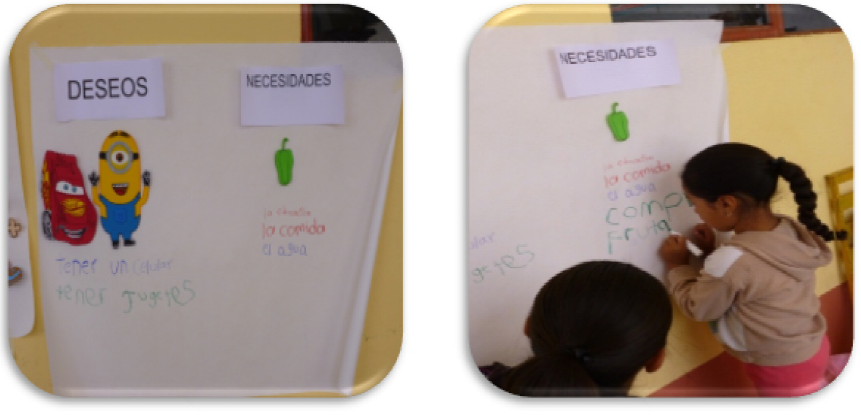

This doesn't mean that the children do not have their own ideas about their savings. For example, in the workshop on financial education, the Chispitas members were able to tell the difference between wishes and needs, which is important since, even when they didn't understand the variation; it was identified when they saw that most of them would destine their savings to their education or to collaborate with the family to purchase foods. The wishes were clearly identified when they say that the least important theme of their savings was buying toys (Figure 4).

Source: Field work carried out in 2013-2014.

Figure 4 Financial education workshop and fortnight meeting.

A piece of data that stands out is the fact that 91o% of those interviewed responded that they expect to finish their undergraduate studies and some mentioned that they want to be teachers, engineers, lawyers, anthropologists, and even one girl, a criminologist; and, also, that they intend to keep saving up to the time when they're adults, showing with this how important the savings activity is for them. This situation agrees with what was found by Guevara et al. (2009), who mention that the level of schooling has a direct impact on the average savings of families, with this probably being associated to the households modifying their decisions regarding consumption-investment and schemes of risk management, as they acquire a higher educational level. With regards to their expectations for when they are older, 38 stated that they do expect to finish their undergraduate studies, while the rest pointed out that they thought they would not be able to.

Complementarily, they were asked if they knew about Fundación Ayú, and it resulted that most of them (35) do not know what it is, although there were seven cases when they stated that they did know about it. Their responses were: in four cases, a group of savers, although two boys mentioned that it is a society that supports Mixtec people; one other mentioned that it represented support for families in the Mixtec Region. We attempted to address the issue of whether the children had participated in any project by Fundación Ayú, in addition to being a Chispitas member, and the generalized response was that they had not participated.

Stemming from the consideration that children save in function of the resources that their parents give to them, they were asked what was amount of money that each one of them saved every fortnight according to the scheme established by the fund. The highest amount was $200.00, but only one of the interviewees mentioned it (2 %); then, 25, 30 and 15 pesos (36 %), $50.00 (19 %), and finally, 100, 40 and 20 pesos (30 %), and 10 pesos (14 %). Of these data we have a maximum amount of savings reported of $200.00, a minimum of $10.00, and an average of $39.29 pesos every fortnight. The importance lies not in the amount of money saved every fortnight, but in the discipline and perseverance with which they are doing it.

In the workshop, the interviewees were asked whether they knew where the money for savings came from, to which they all responded that it was from their father or mother's work, which is related to the responses to the question that asked them to mention three ways in which adults earned money, with work being mentioned more often, followed by the sale of a product, which in the end is one of the tasks that the parents carry out. Savings by Chispitas boys and girls are incorporated to what Boza and Zabaleta (2012) conclude, when they point out that "it is estimated that there are more than 2000 million poor people in the world without access to banks, and they all need to save. Thanks to the creativity and human initiative, people without banks manage to save".

Financial education is a knowledge that can begin at home, since, although considered as informal education, the discipline of saving in adults is a way in which the habit pervades to those who are younger in the household. Therefore, they were asked who had instilled in them the habit of saving, and the results highlight the importance of the participation of women, mothers of the family, since the first answer was that the mother is the one who taught them to save (67 %); however, the second answer could be added to this figure, where they mentioned that it was mother and father who taught them to save (24 %). Other responses included that it was a different member of the family (grandparents or aunts/uncles), with 7 %, while the last response, with minimum percentage, corresponds to the father figure as example of discipline in savings and as motivator to carry it out (2 %). In the financial education workshop, the children identified that money doesn't grow on trees and that the banks don't give it out, but rather that it comes from their parents' efforts. Dolores Alejandra describes:

I live in San Isidro Jaltepetongo. I am 13 years old and I am studying second year of secondary. Every fortnight I save 10 pesos, my mother taught me. I like to save because that way I can buy my school supplies, I want to travel to Mexico City, and also to pay for my uniforms. I think it is important to do it because we can buy our supplies with that (Dolores Alejandra. Chispitas member from the San Isidro fund).

Continuing with the subject of financial education, of all those interviewed only eight know what it means that their money earns interest, and they are the ones who understand that this is what happens to their money in the fund. In simple terms, they explain that earning interest means that the money they save becomes more, so that when the fund is balanced they give them their savings and some more money, which represents the interest gained. Identifying different places where money can be saved was one of the questions in the financial education workshop, and the places more often mentioned were, first, the savings funds with 34 mentions, and in second, banks with eight.

A way to teach boys and girls the habit of saving is the participation of adults in savings schemes, such as the funds for adults from Fundación Ayú. Therefore, it was identified that in all cases it was the father or the mother of the Chispitas member who participated actively as partners and, in some cases, as part of the committees, in both savings funds for adults. As Vargas and Arán (2014) point out, the quality of parenting (understood as the activities that the father and the mother perform in the process of caring, socialization, attention and education of sons and daughters) is a factor that contributes significantly to the cognitive development of sons and daughters. This situation is in agreement with what was pointed out by Conde (1998), who argues that saving in families is based on decisions that the members of the household make in a premeditated way, to guarantee their future consumption through the certainty of an income or acquisition of assets to improve their own wellbeing.

In a complementary way, boys and girls were asked about what they thought about the fact that some people had more money than others. The responses were divided, 27 people said that the main generator of money is work, but it is interesting to see how boys and girls identify that saving is another way to increase resources.

Castillo (2012) refers that saving is, among others, an element that generates foresight, since when a small amount can be accumulated, the savers define better what it is that they want to do with their money. Quite frequently, they establish an aim for their savings, and although the poor live hand to mouth and, therefore, cannot plan the future, with minimum savings this situation changes. This does not impede the fact that in face of an emergency they have to withdraw the savings that they had planned to use for something different. In other words, saving introduces a culture of planning that will have an influence on how to satisfy the most basic needs that otherwise would not be covered.

Savings by Chispitas is one of the important features of the experience analyzed. One explanation of the interest that fathers and mothers show regarding saving by boys and girls could be located in alternative ways of anticipating future needs. Bazán and Saraví (2012) highlight how women, in order to manage the household, consider two ranks of needs: attention to daily life, for which they use the money they receive or earn, and other demands that are not immediate and which require having money available at certain times of the year and situations (school entry, sickness, and other emergencies). This second level of needs could be solved by gaining access to loans from the savings funds of the boys or girls. Thus, the children's savings funds have a double purpose: to teach them to save and to serve as insurance for emergencies.

In addition to saving, children have other reasons that strengthen their appreciation for belonging to the Chispitas group; for 15 of them, the most important aspect is that it is a way to save, but others mention that sometimes they also go on visits to other places. In the fortnight meetings they have fun, and sometimes the Fundación sends them small milk boxes.

Conclusions

The use of microfinances as a strategy to reduce poverty has expanded in the last 30 years, since the initiatives of proposed by Mohammed Yunus were formalized and, although the evidences regarding the impact on the reduction of poverty are not conclusive since there is a large variety of opinions, from those that have found that microcredits do in fact reduce poverty, that they allow generating greater income, that they reduce the vulnerability of households to poverty or empower women, there are other opinions that refer that using microfinances is like placing a band aid on a major surgery, and even, that they are a way of maintaining the statu quo of Neoliberalism. Zapata et al. (2003) mention that there are few studies about the empowerment processes related with savings and credit, so there are still gaps related to the factors that promote or inhibit this process in users.

Whichever the posture may be in this regard, it is convenient to analyze how a strategy undertaken from the civil society, creating microfinances that could even be considered informal, has had an influence on several aspects, such as the perception that savings by the Chispitas is not just child's play, since participation by parents, the discipline every fortnight to attend meetings and contribute their savings pervades the boys and girls as they consider saving as something normal in their lives and, even at their very short age, they can, in some cases, establish objectives or goals to use their savings.

The operation of the funds has great influence on the reduction of transaction costs for adults, since the requirements for income are minimal. For the children there are no requirements and the interest rate, both active and passive, is proposed and approved by all the members of the funds and is not onerous compared to micro-financers that operate formally in the region. The people do not incur in transportation costs, since most can reach the meeting place by walking, with a maximum of time invested of 30 minutes. The funds do not have administration costs, since women's participation in the committee is with an honorary title, they do not have a wage, do not require special facilities or a property purposely built for it; by meeting in the civic plaza of both localities, there are also no expenses for executives or staff for promotion or debt collection. Another important issue is the role that the savings funds have as a source of financial inclusion for inhabitants in the localities where they are located. Although the services they offer are only saving and credit, this allows the users to have access to these at reasonable costs. Some authors mention that greater access of population groups of lower income to financial services could contribute to decreasing poverty and to a better distribution of income.

A third aspect that is worth rescuing about the savings funds is the financial education that is promoted in the children, since when the parents teach by example, their children observe the women's discipline from a young age, and occasionally the father's, of putting aside a certain amount of their income and attending to deposit their saving promptly at the meetings of the funds. In their daily conversations they listen to talk about the interests that the money wins, as well as those that should be paid per concept of the loans received; likewise, in the families there is talk about the destination that they will give their savings or the need to save to face expenses, such as school supplies, or from disease or emergencies. This type of practices generates a space for family participation which, even when the savings are from the parents, generates an activity in common, but also an individual one. Finally, as Castillo (2012) points out, a specific savings strategy can become a permanent learning space, regardless of the level of schooling that they have, since the practice carries implicitly a series of values that with time will build a culture not only of saving, but of participation, legality, accountability, trust and co-responsibility.

A fourth area that is important to make a note of is, as the UNICEF mentions, the exclusion of services and essential goods, such as the appropriate diet, attention to health and schooling, affects that capacity of the children to participate in their communities and societies both now and in the future. Like the dimensions of exclusion, there are factors that are superposed and linked between them, each one worsening the next one until in the extremes some excluded boys and girls are made invisible when their rights are denied, when they go completely unnoticed in their communities, when they cannot attend school, or when they are far from the reach of authorities due to their absence from statistics, policies and programs. Facing this panorama, it is likely that the participation of children in the savings funds could be an element to reduce the risk of them becoming "invisible" from the violation of their rights, which excludes them socially when becoming involved as partners with all the rights that this represents, and with the recognition that the society of their community grants them, since with their savings they can even finance the loans for their parents and other adults in the locality. In this sense, and following Díaz (2010), the participation of boys, girls and teenagers in the children's savings funds could be a possibility for them to be included in the spaces of social life, taking them into account as actors with proposals that are integrated with prominence into the context that they live in, and which allows them, as Gómez and Alzate (2014) suggest, to become social actors subject to full rights, breaking the adult-centrism that has prevailed historically.

This reasoning based on the girls, boys and teenagers belonging to a population group that has been well-tutored historically by the authority of parents or by the State, assuming the idea that solely because of their age they are people incapable of making decisions, for whom they must speak when they have something to say. This limitation in face of adults places the children as part of the sectors of the population most vulnerable to be discriminated in detriment of the exercise of their rights, situation that is further aggravated if, as additional features that contribute to discrimination, the fact of not having money is added, as well as physical appearance, age and gender, additionally exacerbated by intrinsic characteristics of the region where they inhabit, such as having been born in an environment with low schooling level, belonging to ethnic groups or speaking different languages, which makes evident an unequal country that generates different citizens, for the only reason of having been born in certain geographical region. This is evidenced when the Chispitas children were asked how they considered their families, in a scale of very poor, poor, neither rich or poor, rich, or very rich, with 92 % of the responses located in the center, that is, neither rich nor poor; the other 8 % considers they are members of a poor family. As final point, it can be said that financial education taught from early ages will have a permanent impact for their whole life; this can even contribute to being the response for the families to break with cycles of indebtedness and, in the best of cases, with the circle of poverty.

Literatura Citada

Amar, Amar José, Marina Llanos Martínez, Raymundo Abello Llanos, y Marianela Denegri Coria. 2003. Desarrollo del pensamiento económico en niños de la región Caribe colombiana. In: Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, vol. 35, núm. 1. [ Links ]

Banamex-UNAM. 2008 Primera encuesta sobre cultura financiera en México. [ Links ]

Bazán Levy, Lucía, y Gonzalo A. Saraví. 2012. La monetarización de la pobreza. Estrategias financieras de los hogares mexicanos. México: Ciesas, Publicaciones de la Casa Chata. [ Links ]

Bernal Lara, Pedro, 2007. Ahorro, crédito y acumulación de activos en los hogares pobres de México. Cuadernos del Consejo de Desarrollo Social No. 4. Consejo de Desarrollo Social de Nuevo León. [ Links ]

Boza, Chirino José, y José Ignacio Zabaleta. 2012. La riqueza de los pobres. Los Microahorros. In: Revista Atlántica de Economía-Volumen 1-2012. [ Links ]

Campos Bolaños, Pilar. 2005. El ahorro popular en México: acumulando activos para superar la pobreza. México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa/CIDAC. [ Links ]

Carbajal, G. Javier. 2008. Educación financiera y bancarización en México. Documentos de Trabajo No. 8 CEEDE. [ Links ]

Castillo, Alfonso. 2012. Ahorro, vulnerabilidad y estrategias de desarrollo. Un caso en México. MBS. No 2 [ Links ]

Centro para la Inclusión Financiera en ACCION International. 2009. Perspectivas para México de Inclusión Financiera Integral. Informe oficial del Proyecto de Inclusión Financiera en 2020. [ Links ]

CNIF (Consejo Nacional de Inclusión Financiera). 2013. Reporte de Inclusión financiera 5, 2013. Disponible en Disponible en http://www.cnbv.gob.mx/Inclusi%C3%B3n/Documents/Reportes%20de%20IF/Reporte%20de%20Inclusion%20Financiera%205.pdf (consultado el 5 de marzo, 2015). [ Links ]

CNVB (Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores). 2015. Misión y visión. Disponible en Disponible en http://www.cnbv.gob.mx/CNBV/Paginas/Misi%C3%B3n-y-Visi%C3%B3n.aspx (Consultado el 11 de marzo, 2015) [ Links ]

Coates, Kenneth. 2009. Educación Financiera: Temas y Desafíos para América Latina. Conferencia Internacional OCDE-Brasil sobre Educación Financiera. Rio de Janeiro, Diciembre 15-16, 2009: Rio de Janeiro, Diciembre 15-16, 2009: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/16/20/44264471.pdf Consultado el 10 de Febrero, 2015) [ Links ]

Conapo (Consejo Nacional de Población). 2010. Grado de marginación por municipio 2010. Consultado el 28 de Julio de 2014. In: In: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/indices_margina/mf2010/CapitulosPDF/Anexo%20B3.pdf . [ Links ]

Conde Bonfil, Carola. 1998. Ahorro familiar y sistema financiero en México. Tesis Doctoral. UAM. [ Links ]

Delval, Juan. 1983. Crecer y Pensar. La construcción del conocimiento en la escuela. Cuadernos de Pedagogía. Editorial Laia. Barcelona, España. [ Links ]

Delval, Juan. 1989. La construcción de la representación del mundo social en el niño. In: Enesco, l., Turiel, E. y Linaza, J. (eds). El mundo social en la mente de los niños. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

De la Madrid, Ricardo Raphael. 2012. (coord). Reporte sobre la discriminación en México 2012 Crédito. CIDE. Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación. [ Links ]

Díaz, Silvia Paulina. 2010. Participar como niña o niño en el mundo social. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud [en línea] 2010, 8 (Julio-Diciembre): [Fecha de consulta: 11 de marzo de 2015] Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=77315155026 . [ Links ]

Esquivel Martínez, Horacio. 2008. Situación actual del Sistema de Ahorro y Crédito Popular en México. In: Problemas del Desarrollo, enero-marzo, vol. 39, 152. pp: 165-191. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2013. Manual de consulta sobre el ahorro de grupo. Consultado el 5 de marzo de 2015. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/y4094s/y4094s04.htm . [ Links ]

Gómez Mendoza, Miguel Angel, y María Victoria Alzate-Piedrahíta. 2014. La infancia contemporánea. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 12 (1). [ Links ]

Guevara Sanginés, Alejandro, Luis Rosendo Gutiérrez, Omar Stravidis, y José Alberto Lara. 2009. Microahorro y Educación. Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Heimann, Ursula, Juan Navarrete Luna, María O'Keefe, Beatriz Vaca Domínguez, y Gabriela Zapata Álvarez. 2009. Mapa Estratégico de Inclusión Financiera: Una Herramienta de Análisis. El Nido, México [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática) 2012. Información de México para niños. Consultado el 1 de Agosto de 2014. In: In: http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/oax/poblacion/ . [ Links ]

Mansell Carstens, Catherine. 1995. Las finanzas de los populares en México: el redescubrimiento de un sistema financiero olvidado. México, ITAM. [ Links ]

OECD.2005. Improving Financial Literacy: Analysis of Issues and Policies. Paris. [ Links ]

Rutherford, Stuart. 2002. Los pobres y su dinero. México: La Colmena Milenaria/Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Sherraden, Michael, Mark Schreiner, Margaret Clancy, Lissa Johnson, Jami Curley, Michal Grinstein-Weiss, Min Zhan, and Sondra Beverly. 2001. Savings and Asset Accumulation in Individual Development Accounts. Center for social Development, Reporte de Investigación. [ Links ]

Vargas, Rubilar Jaen, y Vanessa Arán Filippetti. 2014. Importancia de la Parentalidad para el Desarrollo Cognitivo Infantil: una Revisión Teórica. In: Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 12 (1). pp: 171-186. [ Links ]

Zapata, Martelo Emma, Verónica Vázquez García, Pilar Alberti M., Elia Pérez N., Josefina López Z., Aurelia Flores Hernández, Nidia L. Hidalgo Celarié, y Laura Elena Garza Bueno. 2003. Microfinanciamiento y empoderamiento de mujeres rurales. Las cajas de ahorro y crédito en México, México: Plaza y Valdés y Colegio de Postgraduados. [ Links ]

Received: March 2015; Accepted: December 2015

texto en

texto en