Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.12 no.1 Texcoco ene./mar. 2015

Contribución especial invitada

What's the issue?

Almost every country in the world is affected by trafficking. It is a global phenomenon and a priority for many governments. Despite this, many aspects of trafficking remain poorly understood. While much work examines the processes and flows of trafficking, very little research has focused on post-trafficking situations. This represents a significant gap in our understanding of trafficking particularly of women's experiences. The negative circumstances many women face on their return 'home' from trafficking situations are severe challenges to them in making new lives and forging sustainable livelihoods. Returnee trafficked women are often stigmatised and face rejection from their family and communities. They are frequently denied services, skills trainings and employment on their return. This report is based on research that sought to bring the experiences of returnee trafficked women centre stage. It aims to promote dialogue on to how to make women's return post-trafficking safe and how to foster a policy environment that responds to their demands for rights to livelihoods. This is a timely intervention as increasing numbers of trafficked women are returning and 'being returned' home, including those who originally left as migrants but return having experienced different trafficking situations.

What is post–trafficking?

Most work on trafficking addresses its causes and characteristics, feeding into policy frameworks targeting the 'rescue' of those experiencing diverse trafficking situations. Post-trafficking starts when these scenarios end. The term post-trafficking describes the processes and practices associated with returning 'home' from trafficking situations, for whatever purposes, whether this involves being trafficked internally in one's own country or elsewhere.

The post-trafficking study

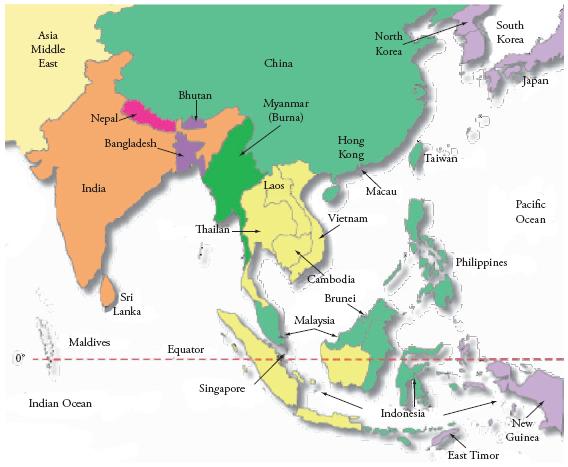

This report draws on a 2-year Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) project on post-trafficking livelihoods in Nepal. Nepal was chosen because it is one of the most important source countries for trafficked women in South Asia and has wider international reach. Women are trafficked to India through the open border and also on to other countries including those in South East Asia and the Middle East.

Another reason for choosing Nepal is that returnee trafficked women, while representing one of the most stigmatised, vulnerable groups, are also beginning to organise around rights to livelihoods. Nepal is home to Shakti Samuha, one of the first anti-trafficking organisations in the world to be formed and staffed by returnee trafficked women themselves. Our research partnership with Shakti Samuha emphasised the coproduction of knowledge. Gaining knowledge grounded in the actual experiences of returnee women provides important insights for post-trafficking situations elsewhere. This is important as not only are the issues faced by returnee women largely ignored, but also the stigmatisation and poverty which they typically encounter means they often have little voice in policy making. A further reason for the choice of Nepal is that it is undergoing democratic reform following over a decade of civil war1. Returnee trafficked women's groups and anti-trafficking organisations have actively lobbied to change citizenship rules which discriminate against women who need a male relative to endorse their application for citizenship on reaching 16. For many returnee trafficked women the stigma and family rejection they encounter makes this process difficult. This adds to their experiences of discrimination and social rejection, effectively making them and any children they may have stateless in their home country upon return. Our project explored the intersections of sexuality, gender and citizenship in returnee women's livelihood strategies as these new democratic processes, supported by national and transnational communities, unfolded. Although our findings highlight an extreme case of discrimination, they can aid in understanding post-trafficking experiences elsewhere where the discrimination may not be so obvious or where citizenship may be less central.

Data collection

The research is based on 46 in-depth semi-structured interviews with returnee trafficked women in Kathmandu and provincial/rural sites identified by government as having high occurrences of trafficking. Professionalisation proved an important aspect of anti-trafficking groups, so a sub set of these interviews (9) were with returnee trafficked women now involved as activists in anti-trafficking. Interviews were taped and transcribed in Nepali and then translated into English. Where we draw on this material in this paper we do so using the idiom of the original translation as we wish to recognise that Nepali English is one of the many forms of global English spoken in the world. A further 15 stakeholder interviews with activists, key personnel in NGOs and government were conducted. The study also analysed discourses and emerging policies on trafficking and citizenship in Nepal and the wider region of South Asia, and tracked the evolution of debates in the Constituent Assembly, convened in 2008 to draft a new constitution.

Key findings

The effects of stigma

• The processes through which a woman's trafficked identity remains hidden or disclosed are important to whether she suffers discrimination and social rejection.

"Police doesn't let you free once they catch you...We were to be handed over to the representatives of [NGO] by police. They [representatives of NGO] had even reached to India to bring us via plane. I had also heard [NGO] also takes pictures and spread the news, thus destroying our izzat (family honour). So I said I wouldn't go to the NGO instead I asked the police to drop somewhere at a border in Nepal. But the police don't work this way." (Sita)

"When I encountered the problem there [India] I through the support of different NGOs was directly brought home by a bus. This is how all the people in public knew that I had encountered problem (trafficking). It had bad impact upon my parents. It definitely perturbed me a lot...I had requested them a lot to drop in the middle. They [Indians] spoke Hindi, however I could also speak bit of Hindi...[but I couldn't convince them]." (Nita)

• A key issue is the destinations to which women are trafficked to, as well as the regions they come from and return to, reflecting geographical hierarchies of stigma.

• Returning to their home communities is often difficult and women may be forced to migrate internally to maintain anonymity.

"The society perceives differently to women trafficked to Delhi, Calcutta and women trafficked abroad such as [to] Lebanon, Kuwait. It is seen as they have nice work in Kuwait or Lebanon".

Q: What about women trafficked in Nepal?.

"People will definitely backbite against her if not directly...though the stigma is not same as to those returning from Bombay". (Rupa)

"You can't hide it from your neighbours and people surrounding you providing that you are living in your own village. You can hide it just not opening up your mouth to anyone if living in places other than your village." (Bindu)

Livelihoods and skills trainings

• Individual strategies of dealing with stigma and poverty focus heavily on the labour market and count on local NGOs, who provide skills-training including traditional female occupations/skills such as sewing and carpet making.

• Some 'non-traditional' female jobs can be better livelihood options for women.

• However this raises issues about male-dominated workplaces, and related issues of confidence and personal safety.

• In the case of self-employment through small businesses 'outing' women as trafficked can also be problematic, affecting the sustainability of the enterprise.

"It was hard living in the village. The people gossiped. I opened one small tea shop. One of my friends who is a member of Shakti Samuha had given me 1000 Rs. It was at Sindhupalchok. Ten minutes from my home. It was again very difficult. I used to make tea, local wine there and the men used to show me disrespect - trying to grasp me, touch my hands, talking in a stupid way, throwing stones on me. It was very embarrassing." (Sushila)

Marriage

• Marriage remains one of the key livelihood strategies for returnee trafficked women to manage stigma and poverty, and also facilitates their access to citizenship and livelihoods in post-trafficking situations.

• However, this research also suggests marriage is not always a durable option for women on their return as they may experience sexual and physical violence if their trafficked identity becomes known to their husbands and families.

"I was trafficked through a marriage...and 'remarried' on my return to get my citizenship....but beaten by husband, he started calling me a prostitute, he 'remarried' to another woman, I'm separated...thinking for a divorce." (Sita)

Citizenship

• Returnee trafficked women (and their children) can face difficulties in obtaining Nepali citizenship, which severely limits women's livelihood options, as well as access to government services (health, education), housing and legal transactions.

• Citizenship is also seen as a key mechanism in terms of establishing/maintaining one's identity as 'respectable' and 'trustworthy', and marks difference between migrant and trafficked women.

"If you don't have a citizenship card it can be very problematic...I wouldn't be able to open my bank account. Similarly I couldn't get my marriage certificate and my children's birth certificates. And I could not be able to look for job also. ...You don't get work if you don't have citizenship card. Moreover, you need to have it in order to get a room to live."(Maya)

Professionalisation and celebrity in anti-trafficking advocacy and activism

• Anti-trafficking activism is constrained by transnational, donor and state policies (for example, the annual TIP report2 which promotes a focus on criminalising trafficking) often therefore side-lining the livelihoods issues affecting women post-trafficking.

• Processes of professionalisation on anti-trafficking activism and advocacy are impacting the sector widely, including individual trafficked women, NGOs and donors. However skills gaps mean that trafficked women themselves often cannot take advantage of opportunities to work in these or related sectors, however much they might want to.

"I would like to work with anti-trafficking NGOs because I myself have encountered trafficking. Therefore, I from my real experiences can make people better understand the issues" (Rita)

• The impact of grassroots celebrity awards on anti-trafficking professionalisation produces costs and benefits at both individual and collective levels. These include: greater public awareness leading to a higher profile of trafficking organisations and issues, which may attract more returnees and increased access to funding. However, awards may also produce a risk of disclosure, as well as increased danger, divisions and splits.

"Earlier I could freely go in the communities and approach the sisters and do the activities on my own, without any problem and without any fear. Trafficking is an organized crime and it has very organised network. There was no fear for me in the past. But now after this event and publicity people know me as Charimaya fighting trafficking issues; it wouldn't be as easy as it was before for me to go to the communities." (Anu)

Recommendations

• Recognise and address post-trafficking issues (after 'rescue').

• Bring trafficked women's voices/perspectives/experiences into the policy making process, and in anti-trafficking advocacy and activism.

• Put in place mechanisms that recognise where and how women are vulnerable to being trafficked while undertaking a formal migration process.

• Ensure definitions of trafficking (and interventions) reflect how trafficking and post-trafficking is experienced and understood at grass roots levels and especially in provincial areas.

• Recognise and address how policy and NGO practices can negatively influence returnee women's ability to manage potential stigmatisation by 'outing' them as trafficked or by raising 'markers of doubt' around their identity.

• Consider the psychological and personal safety repercussions of marriage being a dominant livelihood option for stigmatised returnee trafficked women.

• Provide professionalisation pathways into other advocacy and policy sectors that build on the transferability of returnee trafficked expertise and sector specific knowledge.

• Uphold citizenship rights of returnee trafficked women and their children as an underpinning element of sustainable lives and livelihoods.

For further information

This summary is produced from a research project, 'Post Trafficking in Nepal: Sexuality and Citizenship in Livelihood Strategies' (2009-2012), undertaken by Newcastle University in partnership with the non-governmental organisation Shakti Samuha and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) Mission in Nepal. The research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC RES-062-23-1490).

Read more about the Post Trafficking in Nepal project and download this report at www.posttraffickingnepal.co.uk.

School of Geography, Politics & Sociology

5th Floor Claremont Bridge

Newcastle University

Newcastle upon Tyne

NE1 7RU

Email:

diane.richardson@ncl.ac.uk

nina.laurie@ncl.ac.uk

meenapoudel12@gmail.com

janet.townsend@ncl.ac.uk

1 13 February 1996 – 21 November 2006.

2 The Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report is compiled by the US State Department and ranks countries on the basis of the mechanisms that are in place to tackle trafficking.