Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.2 no.2 Texcoco jul./dic. 2005

Panel estimators that combine travel cost and contingent behavior data sets for evaluating protected areas

Estimadores de panel que combinan información de costos de viaje y conjuntos de datos de valoración contingente para evaluar áreas naturales protegidas

Antonio Kido 1, Andrew Seidl 2 y John Loomis 2

1 Economía. Campus Montecillo. Colegio de Postgraduados. 56230. Montecillo, Estado de México. (ankido@colpos.mx).

2 Colorado State University. Clark B-320. Fort Collins, CO. 80523.

Abstract

Although conservation policies and practices have always been influenced by political and economic factors, economic analysis has played a limited role in conservation decision making until recent years. Many people are realizing that the fundamental forces driving the loss of biological diversity (e.g. land conversion and over exploitation of natural parks) have economic roots. This paper extends a fairly conceptual innovation used by Cameron (1992) for measuring impure public goods. A model was developed using the information of a travel cost set and a contingent behavior set by imposing restrictions in the cross equation parameters without losing consistency in the utility function specified. The present value of tourism visits to the monarch butterfly sanctuary using the probit model was calculated from a range of discount rate options. This present value ranges from 35 to 80 million dollars. The own price elasticity for the model using admission fees was also estimated for calculating the revenue maximizing admission fee. The optimal entrance fee from the landowners' perspective was calculated at 15 dollars.

Key words: Stated information, revealed information, random probit model, impure public goods

Resumen

Aunque las prácticas y políticas de conservación siempre han estado influenciadas por factores políticos y económicos, el análisis económico tuvo una influencia limitada sobre la toma de decisiones en conservación hasta hace pocos años. Cada vez más gente está entendiendo que las fuerzas fundamentales que producen pérdida de la biodiversidad biológica (e.g. conversión de tierras y sobreexplotación de parques naturales) tienen raíces económicas. En este trabajo se extiende una innovación relativamente conceptual usada por Cameron (1992) para medir bienes públicos impuros. Se desarrolló un modelo usando la información de un conjuto de costos de viaje y de valoración contigente imponiendo restricciones a los parámetros de la ecuación generada sin perder consistencia en la función de utilidad especificada. Se calculó el valor presente de las visitas turísticas al santuario de la mariposa monarca usando un modelo Probit con un intervalo de opciones de descuento. Ese valor oscila entre 35 y 80 millones de dólares. También se estimó la elasticidad del precio de demanda usando la cuota de entrada como variable Proxy, para calcular la cuota de admisión que maximiza el ingreso. Desde la perspectiva de los dueños de la tierra, la tarifa óptima de entrada se calculó en 15 dólares.

Palabras claves: Información declarada, información revelada, modelo aleatorio probit, bienes públicos impuros.

Introduction

The economically efficient allocation of natural resources often suffers from a lack of direct or indirect market signals reflecting their true value to society relative to other economic goods and services. This issue can be due to the characteristics of the natural resources to be managed or to the ineffectiveness with which market institutions reflect these values.

The economic analysis of protected areas can proceed from a variety of scales and focus on one or more of several types of economic value. For example, private or government area managers capture entrance fees from tourists who have traveled to experience the native flora and fauna of the region. Economic analysis could proceed to estimate the profit maximizing entrance fee through an understanding of current visitors' sensitivity to fee structure changes. This estimate would facilitate entrance pricing strategies, but would not provide information beyond the park gate from which to make broader investment decisions about natural areas relative to other economic goods and services. An estimate of the total economic value of the reserve to tourists might facilitate the establishment a broader policy.

However, the benefits from the reserve may reach (besides residents and visitors) people who find value in knowing that protected areas exists, but have no intention of visiting them and, therefore, have little avenue to register the depth and extent of their value for the reserve or the flora and fauna found within it. These values may be quite real and important from a broader management perspective, but will never find their way to local reserve managers or neighboring communities through markets. A distinct economic analysis and policy would be required to reveal such values and to provide the appropriate incentives towards optimal resource management.

In this study we undertake an economic analysis of visitation to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, in Michoacán, México, in order to present several options of management, administration and valuation of natural areas. We use innovative economic valuation and statistical techniques to derive optimal pricing strategies at the reserve gate, from the perspective of reserve managers/owners. The total economic value of visitation to the biosphere reserve was calculate using travel cost and contingent behavior methods. We do not derive total economic value at a global scale, but explore the management options appropriate to value existence rather than visitation. We hope that this analysis illustrates some of the economic valuation and policy challenges facing the direct and indirect stewards of our global natural heritage on our behalf.

Conceptual basis for the economic valuation of natural resources

When cost-benefit analysis started in the United States of America in the 1930's, economic valuation was generally perceived in terms of market prices. To value something, one ascertained an appropriate market price, adjusted for market imperfections if necessary, and then used this to multiply some quantity (Hanemann, 1994). However, a theoretical development changed this situation.

The theory of public goods (Samuelson 1954, 1964) is often referred to justify public ownership of property. Pure public goods are both non-rival and non-exclusive. Non-rivalness means that consumption by one individual does not reduce the quality or quantity of the good available to other consumers. Non-exclusiveness means that there is no way to prevent others from making use of the good. These two attributes impede the allocation of these kinds of goods using markets institutions (Hendry, 1993). However, the important issue to determine is whether protected areas are public goods by nature. Some people suggest that protected areas have attributes of both public and private goods. People who believe that biodiversity conservation is for the benefit of all people, including future generations, argue that biodiversity is a public good. On the other hand, many of the benefits from protected areas such as tourism are private (Clark, et al. 1995).

Gradually, the list of impure public goods has expanded to include, among others, protected areas, schools, highways, communication systems, information networks, national parks, and waterways. Thus, any theory that could analyze the allocative and distributive aspects of such a wide range of goods would indeed make an important contribution to the theory of public finance (Cornes and Sandler, 1986).

In tourism, many forms of congestible public goods are relevant. For example, too many visitors at a destination crowds beaches or protected parks. It is concluded that admission of additional users could continue, and the density of users increases, until aggregate net benefits were maximized. The essence of the analysis is that optimal capacity for a site is dictated by its users' perception of, and preferences for, congestion. This empirical work intends to estimate the non-consumptive use of the sanctuary of the monarch butterfly using combined (revealed and stated) preference information and measuring congestion and economic benefits to landowners of the sanctuary when entrance fees vary.

Materials and Methods

The model

The particular character of tourism makes many traditional valuation techniques difficult or inappropriate to apply for welfare estimations. Some models cannot be used to derive a demand function for the recreational service, since the site is visited only once. However, Hanemann (1984) showed that the problem of Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) discrete choice could be recast as a visit/no visit decision at current trip costs and higher trip costs under a utility difference framework. Consider first the decision to actually visit the site. Let utility of individual i (Ui) be defined as the sum of deterministic (Vi) and random components (∈i); where the ∈i are independent and identically distributed random variable with zero mean that reflects components of the utility function unobservable to an analyst. Let Vij(Yi-TCi-EFo, Q = 1) be the deterministic utility from taking a trip when site quality does not change (i.e. Q=1), where Yi is income, TC is travel cost and EF0 is entry fee. If the individual does not make the trip, the deterministic part of utility is Vi0 (Yi) assuming weak complementarity, that is, site quality does not matter when the site is not visited. If we observe the individual at the recreation site, then the utility difference must satisfy:

This utility difference is driven by the observable trip choice and hence may be considered revealed preference information. If we add the contingent visitation behavior question at a higher travel cost and obtain a positive response, we can infer that the utility difference must also satisfy:

If the response is no, then

The statistical model for testing differences between stated and revealed preference responses and incorporating the panel nature of multiple responses per person, and using the random error-component approach, was developed as:

where Zi=1 if the person does visit the site and zero otherwise (under different admission fees); TC+EF is the average travel cost to the site with contingent behavior scenarios for entrance fee; I represents the average income from visitors, and DC is an index number for measuring people's perception of congestion. DCB is a dummy variable (0,1) to test whether stated preference responses shift the probit b vector, and DCB (TC+EF) is another dummy variable that interacts stated preference information with the price variable to test whether there is a price slope difference with stated preference responses. θi is the unobservable characteristic specific to each individual, and ωit is the transitory error across individuals. In this way, differences in individual preferences will result in some individuals switching from visit to nonvisit status when the variable price changes. In this contingent behavior model, β0 can be interpreted as the utility of choosing to visit the site (independent of the cost) relative to the utility of not visiting the site.

Data

Background of the study area

The special biosphere reserve of the monarch butterfly is a protected area located in the vicinity of ten municipalities, but only five ejidos surround the buffer zones of the most important sanctuary open to visitors. Five sanctuaries have been established in the reserve, but only two of them are open to tourists: El Campanario and Sierra Chincua. Both are located between the two gateway communities of Angangueo and Ocampo. The Sierra Chincua sanctuary was opened to visitors on December 10, 1996. El Campanario has been open to tourism since 1980, and it is the main destination for visitors. El Campanario is located in the ejido El Rosario. Although the mexican federal government controls the sanctuary, and since the sanctuary is on ejido land, the ejidatarios (members of the ejidos) have preemptive rights. They charged an entrance fee of 15 pesos ($1.50 US) per person for the 2000-2001 season.

The monarch butterfly sanctuary is somewhat unique as a biosphere reserve, as it is found on ejido rather than strictly public lands and is, therefore, subject to potentially more different management incentives than are most biosphere reserves in México or worldwide.

An entrance fee can be considered a powerful policy instrument to restrict or to encourage visits to a sanctuary. The specific question regarding different entry fee scenarios was formulated as: would you had visited the sanctuary if the entrance fee were a) $2.50, b) $5, c) $10, d) $25?

Data on current travel cost and distance traveled were included in the survey, as well as questions regarding demographic characteristics of visitors. The survey process consisted in the administration of a total of 450 questionnaires during all the weekends in february and march of 2002. Less than 5% refused to answer. From the total of 450 questionnaires, 407 were used in the analysis, which contained complete information on the contingent questions.

Results and Discussion

Of the statistics of the sample, it is important to mention that the average actual cost per visitor was 54.77 dollars (under different scenarios of entrance fee). The average age of respondents was 42 years. The education level, on average, was high school. The monthly income average was 498.77 dollars.

In Table 1 the variables and units used in the specified model are presented. The TC+EF variable represents the total cost per person plus the cost established for the different scenarios of entrance fee. The congestion variable was initially established as an index from 1 to 10 measuring people's perception congestion. However, better estimates were obtained using an index from 1 to represent low perception of congestion (up to 4 in the 1 to 10 scale) and 2 representing moderate and high perception of congestion (from 5 to 10 in a 1 to 10 scale). Education represents the years of schooling of the interviewed people. The income variable was specified in five different ranges of per month salary. In the model estimation, the minimum amount of the salary was established at 200 dollars, and the maximum at 800. For the other ranges, the mean value of the range was used. DCB is a dummy variable coded as 1 for actual behavior and 0 for contingent response, and DCB (TC + EF) is a dummy variable coded as 0 for actual and 1 for contingent response, to test for whether a response being actual versus contingent behavior influences the price slope.

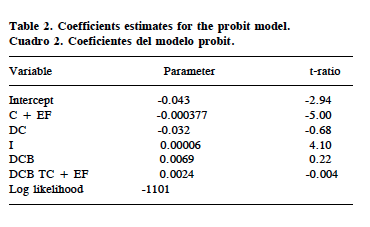

Regression results from the model for estimating visitation at the sanctuary of the monarch butterfly are presented in Table 2. All of the signs of the estimated coefficients are as expected; however, congestion is not significant.

The own-price coefficient is negative and significant; that is, when entrance fees increase, visitation declines. The income coefficient is positive and significant, reflecting the importance of income in influencing visitors' decisions. The congestion coefficient is negatively signed as expected, but it was not significantly different from zero, which precludes us from making any inference about this variable. Therefore, there is no measured congestion effect on visitation within the range of our data. The dummy variables for stated and revealed behavior were not statistically significant, indicating no systematic difference between revealed preference response and contingent behavior response.

Hanemann (1989) shows that with a linear utility difference model with unrestricted mean and median the WTP (willingness to pay) of a trip with different levels of entrance fee would be: WTP(TC+EF)=(ß0+ß2(I))/ß1. Using the above formula, the value of the consumer surplus per person was found at 35.45 dollars. Total welfare (W) is equal to consumer surplus per person times visitors in the season, and using a 4% discount rate, the net present value of tourism visits (NPV= W/r) to the sanctuary was calculated at 86 million dollars for the whole season. Since there is little agreement on the correct discount rate for valuing natural resources, a sensitivity analysis of the present value of tourism visits to the sanctuary is presented under different discount rates (Table 3).

The estimated demand function and the own price elasticity allow us to analyze how the revenue of the site can be maximized. According to the estimated demand function for the entrance fee variable and the current entrance fee ($1.50), the sanctuary is being operated with an own price elasticity of -0.37, which means that is being managed within the inelastic range of the demand curve, where the total revenue can be increased with increases in price. Therefore, the sanctuary's revenue would increase if higher entrance fees were charged.

Because the site only receives the entrance fee, and other sources of income are not available, the total revenue of the reserve is:

R = (entrance fee) * ( number of visitors)

Using the park visitation demand relationship and the calculation of elasticities at each fee level reported above, the revenue-maximizing fees of the sanctuary are shown in Table 4. The landowners obtain $146 587 as revenue when they charge an admission fee of $1.50. The number of visitors for the 2001-2002 season was estimated at 97 725. If the entrance fee were $5.0, they would make $273 630 from visitors. With a $15 fee they would make $571 695, but a $16 fee would raise only $515 988, making less revenue than with a $15 dollar fee. Thus, the optimal fee for landowners is $15 dollars per person (Table 4). Table 4 also shows that a 61% reduction in visitation would take place at a $15 fee, reducing the public enjoyment and education provided by the butterfly reserve.

Conclusions

This paper presents an economic valuation of the monarch butterfly sanctuary, using only non-consumptive values in the evaluation. In order to avoid the criticisms of the traditional zonal travel cost method, a fairly recent technique was included using a combination of two methods (travel cost and contingent valuation) in the production of a single new data set. The random effects probit model was specified for the panel nature of the information, and the present value of tourism visits to the sanctuary was calculated with a range of discount rate options. This present value ranges from 35 to 86 million dollars.

The own-price elasticity for the model using admission fees was estimated at -0.37. The optimal entrance fee from the landowners' perspective was calculated at 15.0 dollars, suggesting that a policy option to compensate landowners would be to let them increase the entrance fee to the sanctuary in order to maximize revenue.

References

Cameron, T. A. 1992. Combining contingent valuation and travel cost data for the valuation of nonmarket goods. Land Economics 302-17. [ Links ]

Clark, C., L. Davenport, and P. Mkangal 1995. Designing policies for setting park users fees and allocating proceeds among stakeholders. The World Bank. 20 p. [ Links ]

Cornes, R., and T. Sandler 1986. The theory of externalities, public goods, and club goods. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 530 p. [ Links ]

Hanemann, M. 1984. Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete choice responses. Am. J. Agr. Econ.: 1255-1263. [ Links ]

Hanemann, M. 1989. Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete choice data: Reply. American Journal of Agricultural Economics: 1057-1061. [ Links ]

Hanemann, W. M. 1994. Valuing the environment through contingent valuation. Journal of Economics Perspectives (8): 19-25. [ Links ]

Hendry, R. 1993. User pays, who pays?. Proceedings Annals Conference. Brisbane. 37 p. [ Links ]

Samuelson, P. 1954. The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics (36.4): 387-89. [ Links ]

Samuelson, P. 1964. Public goods and subscription TV: correction of the record. Journal of Law and Economics 517-21. [ Links ]