Introduction

In the summer of 2019, the final report of the Canadian National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Reclaiming Power and Place (referred to throughout as “the Report”), was presented at the Canadian Museum of History in Québec. It concluded that State actions and inactions rooted in colonialism and colonial ideologies have targeted the lives of thousands of Indigenous women, girls and members of the 2SLGBTQQIA (two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual) community, and therefore amount to genocide (NIMMIWG, 2019a). This was not the first time that Canadians have been confronted with such statement. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reached a similar conclusion: Indigenous peoples had been, and were still victims of an ongoing genocide (TRC, 2015a). But, if such a conclusion had been reached before, why explain genocide, and the destruction it entails, through a specifically gendered lens? Or, rather, what does gender have to say about genocide, particularly for the case of Indigenous peoples? What was strikingly novel about the Report was the connection it traced between the colonial construction of understandings around gender and sexuality, and a current human rights crisis. Nonetheless, although the Report elaborates on the gendered impacts of genocide, it does not make a clear statement on gendering as genocide. This consideration is the starting point of this article.1

The aim of this piece is to push forward the debate around gender and sexuality as categories of analysis in genocide studies. Through a feminist lens, my objective is to provide evidence that the concepts of gender and sexuality have value for genocide studies beyond analyzing the gendered effects of genocide. The racialization of the Indigenous peoples and their subjectification as “women” and “men” (as understood from a Eurocentric perspective), were interlinked processes that established a destructive hierarchy in settler colonial societies, one that continues today (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 233). Most of the literature I collected for this research falls short in using a gendered lens to analyze how the violent imposition of heteropatriarchy and compulsive heterosexuality have impacted Indigenous men. Although there is a significant gap to further our understanding of this issue, some scholars provide preliminary insight. Arvin, Tuck and Morril, explain that when First Nations activists in the 1980s fought to overturn the sexist ideologies of Canada's Indian Act of 1876, many who identified as First Nations men were intensely hostile to these changes (2013). Paradoxically, these opponents appealed to settler colonial gender norms to blame Indigenous women for being feminists, and therefore complicit with a history of colonialism and racism. From a more inquisitive angle, another group of scholars has recently reframed the debates over the Indian Act as not simply a matter of First Nations people who identify as men versus those who identify as women, but rather as another site where settler colonialism effectively operates through heteropatriarchy (Barker, Million, and Simpson as cited in Arvin, Tuck and Morril, 2013, p. 22).

Although these are introductory observations, they pose challenging questions about the differentiated effects of the imposition of heteropatriarchy. Therefore, interrogating how the current understandings of gender originated may have implications for how we think about the meaning of genocide and what it means to destroy a group, or a genos. As such, gendering is one element of a broader range of destructive practices against Indigenous peoples, such as mass displacement, livelihood destruction, and dispossession.

Gender theory and genocide theory do not often intersect, because both tend towards certain assumptions about each other's founding conceptualizations. Genocide studies are generally2 entrapped within an understanding of gender as something that is always existent in every genos, and therefore a gendered analysis can only illuminate what is already intrinsic to a particular group. On the other hand, gender studies hardly engage in discussing what is it that makes genocide a particular form of destruction. In some cases, the term is used as synonymous with mass murder, and in others it is invoked as a form of deeper, more insidious violence, without detailing what is it that is actually destroyed.

Against this context, the question I intend to provide some answers to is: what is destroyed by genocide? Echoing Tricia Logan, I consider the implicit connections between what Raphael Lemkin originally conceived as “physical” and “biological” genocide and “cultural” genocide as one and the same, since Indigenous conceptions of life comprise both physical and cultural dimensions (Logan, 2015). When Indigenous ontology, educational systems and family structure are threatened or destroyed, so can be the lives of the people in the group or genos. This article asks how a culturally Eurocentric construction of gender, imposed upon colonized Indigenous peoples, can contribute to the genocide of such group. What assumptions around gender and sexuality are informing genocide studies? How are gender and patriarchy central to the very structure of colonialism? I am particularly interested in tracing the links between the concept of social death (Card, 2003) and the institutionalized gendered violence of a settler colonial state, in this case Canada.

This article centers the Canadian Indigenous genocide as relevant for the literature of genocide studies not only because it has been underre-presented, but because the case study has some particularities that have limited the discussion even among Canadian scholars (Woolford and Benvenuto, 2015, p. 375). The national Canadian mythology of the “peaceful frontier” (term by Logan, as cited in Woolford, Benvenuto and Hinton, p. 375) derives from stories of early European settlers having relatively peaceful relations with the Indigenous peoples and being “included” in the building of the nation. The name “Canada” alludes to this first encounter; it originates from Kanata, which refers to “village” or “settlement” in Huron-Iroquois.3 Against this background, naming Indigenous experiences as genocide seems out of place, since, at most, some of them were victims of mass murder, nothing similar to the scale of the Holocaust as the paradigmatic genocide. It also relates to the construction of Canadian national identity as more benign than that of former slave trader nations, and even as having a higher moral ground in the international sphere when it comes to genocides, as many Canadians have offered their assistance as “rescuers” in these conflicts (Razack, 2007).

Colonization refers to the processes by which Indigenous peoples are dispossessed of their lands and resources, subjected to external control, targeted for assimilation and, in some cases, extermination (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 231). Settler colonies were primarily established by displacing Indigenous peoples from their land, and are premised on their elimination (Wolfe, 1998). As Patrick Wolfe argues, “the split tensing reflects a determinate feature of settler colonization”: the colonizers come to stay, and thus “the invasion is a structure not an event” (1998, p. 2). Before further developing this argument, I must clarify how the term “Indigenous” is employed in this work. In Canada, Indigenous peoples are far from being one homogeneous group; they only came to be regarded as such while the process of settler colonization developed and, in turn, they became racialized. The Canadian constitution recognizes them in three categories: Inuit, Métis, and First Nations, but there is significant diversity within them. Paraphrasing the National Inquiry, if I were to examine Canada's relationship with all of these groups individually, I could conclude that there have been hundreds of genocides (NIMMIWG, 2019b, p. 13). However, for the purposes of this analysis, I will mostly refer to Indigenous peoples collectively, and only address the aforementioned categories when speaking of particularities.

The concept of social death

The concept of social death that guides this research is taken from Claudia Card, who aims to respond to the question: what is destroyed by genocide? (2003). She argues that the terminology of genocide is necessary because the kind of harm suffered by individual victims of genocide, in virtue of their group membership, is not captured in the definition of other criminal actions (Card, 2003, p. 68). When a group with its own cultural identity is destroyed, its survivors lose their cultural heritage and may even lose their intergenerational connections. She draws on Orlando Patterson (1982) to argue that, if such a crime takes place, the members of a group may become “socially dead” and their descendants “natally alienated”. Consequently, they won't be able to inherit and build upon the traditions, cultural developments, and projects of earlier generations (Card, 2003, p. 73). In sum, Card's approach is that at the core of genocide is the experience of social death, not necessarily physical death, achieved through mass killing.

This conceptualization of genocide challenges Lemkin's differentiation of “cultural genocides” (1944). In Card's view, the central evil of genocide is the intentional destruction of social vitality in a community, defined as the relationships, contemporary and inter-generational, that create contexts and identities that give meaning and shape to our lives (2003, p. 73). Thus, if social death is central to genocide itself, the term “cultural genocide” is redundant, for social death implies cultural death as well. Although Card does not elaborate on the relation of her conceptualization with Indigenous experiences4 (Card, 2003; 2010), her proposal provides a starting point to identify them within the context of genocide. Just as Logan convincingly argues: “physical” genocide and “cultural” genocide are one and the same, since Indigenous conceptions of life comprise both physical and cultural dimensions (Logan, 2015, p. 435). For instance, carrying out particular ways of life may depend on having the land to do so; if that land is lost, the conceptual framework for living breaks down, even if the people are still physically alive. Following the same logic, when fundamental organizing principles in societies, such as understandings around gender/sexuality, are eliminated and replaced by others, the process could be called genocidal.

Gender, sexuality and genocide studies

Gender and sexuality have remained marginal in genocide studies. There are relatively few efforts to problematize the concept against the core discussions in the field, for instance those related with the actors involved, the intent, and what it is that makes genocide a distinctive kind of destruction worthy of study. Gender has been mainly understood as a category of analysis to identify the difference between female and male experiences of genocide or genocidal violence. Yet, as I will explain, there are significant limitations in this understanding.

Elisa Von Joeden-Forgey (2010a; 2010b; 2012; 2015) has led the efforts to include gender as a category of analysis in genocide studies. Her main thesis is that the consideration of gender is crucial to understanding this crime because genocide is, at its core, about stopping group reproduction (2010b, p. 2). She argues that the perpetrators target men and women according to their perceived and actual positions within the reproductive process as a means to achieve the destruction of the group. In other words, they aim to destroy their “life force” through what she named “life force atrocities” (2010b, p. 2). Central to this term is the idea of family as the institution that organizes the reproduction of life force. From this perspective, she suggests that the targeting of women hinges on the fact that they are “universally accorded primary care-taking responsibilities” (2010, p. 10). In a subsequent work, she emphasizes the importance of moving beyond gender-based violence to explore which ideas about gender are implicated in the crime -for example, those regarding violent masculinities- that might make a society more receptive to genocidal ideas (2012, p. 93). However, though Von Joeden-Forgey's proposal may prove valuable for the contexts she references (i.e. Rwanda, Bosnia, the Holocaust), I consider that her use of the concepts around gender and family are far from universal, and must be historically and culturally located.

Von Joeden-Forgey also contributed to the only book I found that was specifically concerned with this topic: Genocide and Gender in the Twentieth Century. Edited by Amy Randall, this book contains works by fifteen scholars that echo the main approaches I identified: gendered experiences of men and women as victims and survivors (Fein, 1999); sexual violence and mass rape -mainly against women- as genocidal tactics; the relevance of masculinity and femininity in the perpetrator's motives (Labenski, 2019); and the inclusion of a gendered lens in international criminal law. Randall's piece highlights that the volume “sheds light on how discourses of femininity and masculinity, gender norms and understandings of female and male identities contribute to victims' experiences and responses” (Randall, 2015, p. 1). Yet, it is relevant to note that both this book and the majority of literature concerned with gender are part of comparative genocide studies, and thus focus mainly on the Holocaust and the genocides in Rwanda, Armenia, and Bosnia. Comparative genocide studies, as the dominant perspective in the field, have been challenged by several authors (Shaw, 2012; Moses, 2008) and, as I will expand further on, tend to rely on Eurocentric assumptions of gender as if the concept was ahistorical and universal.

In contrast with the case of genocide studies, the concept of genocide appears to be more central to gender studies, specifically regarding Indigenous and decolonizing feminist perspectives. It is widely recognized that Indigenous peoples, not only in the American continent, but also in the Pacific Islands, Australia, and other territories where settler colonizers have established themselves, have been victims of genocide; nevertheless, the scholarly use of this concept also has its shortfalls. I do not intend to say that applying the label of genocide to these cases is inaccurate in any way; As Logan assertively clarifies, Indigenous peoples “know painfully too well what the term means to them, where the term comes from and how it should be understood” (Logan, 2015, p. 435). My suggestion is that, by further elaborating on its complexity and unpacking its genealogy in the context of international politics, the weight and meaning it holds has the potential to be strengthened. Furthermore, I will explain how gender and patriarchy are central to the very structure of colonialism, and how that amounts to a form of destruction in what María Lugones called the modern/colonial gender system (2007).

The first works that emerged when trying to bring a gendered lens to the study of genocide were rooted in second wave feminist literature. Although they was later criticized for trying to argue that women, on the basis of their sex, somehow suffered more than men in genocides, subsequent literature tried to resolve the issue by using gender as an ontological category without problematizing its origins (Von Joeden-Forgey, 2010, p. 64). Nevertheless, the categorization of “woman” in feminist discourses as a homogeneous, bio-anatomically determined group that is always already constituted as powerless and victimized does not consider that gender relations are social relations and, therefore, historically grounded and culturally bounded (Oyěwùmí, 1997, p. 1055). Gender and sexuality are cultural constructs. This means that “woman” and “man”, as categorized by most genocide scholars occupied with gender, do not necessarily exist outside of Western culture, which is just one of many around the world (Oyěwùmí, 1997, p. 1050).

Oyěwùmí's contribution is considered pivotal for decolonizing gender studies and set the base for robust critiques of second wave feminism. In particular, her critique of the use of gender as explanans can be further addressed for the case of genocide studies. Firstly, she poses that gender does not simply identify already existing puzzles; it can actually constitute them. As an analytical tool, gender is not neutral, since it does not merely describe the world, but also inscribes it (Oyěwùmí, 1997, p. 1060). Her critiques were based on the case of the Yoruba people from Western Africa: she argued that gender was not an organizing principle in Yoruba society prior to colonization, and that the imposition of the heteropatriarchal binary led to the subordination of females in every aspect of life (1997, p. 1053). Indeed, Oyěwùmí refers to Native American cultures to give an example of how nature, or genitals, do not determine “woman” or “man” (1997, p. 1057). Thus, her analysis constitutes a first step towards identifying gendering as part of colonial violence.

However, a commonly overlooked critique to Oyěwùmí's contribution is the one made by Rita Laura Segato. She disagrees with Oyèwùmí's view that colonialism introduced the vocabulary and practices of gender in Yorubaland, and that there was an absolute absence of a symbolic gender structure in traditional, precolonial Yoruba society (2003, p. 337). Using numerous examples from the findings of her ethnographic research with the Yoruba in the “New World”, specifically Brazil, she states that it is not that the Europeans imposed new social relations based on the body, but that these relations were ordered in a different way to those of the Yoruba (2003, p. 341). One of her examples is that male anatomy was indeed linked to a condition of status and prestige that was not compatible with a wifely social role, except under the command of a supernatural entity (2003, p. 343). In other words, rather than gender itself, colonizers imposed a high-intensity gender binary that was alien to the Indigenous populations, since it was essentialist and non-flexible. In my opinion, Segato's clarification provides a narrower framework to analyze the case of gendering as genocide: what holds destructive potential is not simply the imposition of a binary, but the drastic shift it produces upon intersecting power dynamics.

One of the strongest arguments around the relation between colonialism and the imposition of heterosexism is made by María Lugones, through the concept of the coloniality of gender. Lugones argues that sex is not unproblematically biological and that gender is a violent, colonial introduction that is consistently and contemporarily used to destroy peoples, cosmologies, and communities as the building ground for the “civilized” West (2007). Colonialism imposed a new gender system, based on a sexual binary, that was different not only to that of the Indigenous peoples, but to that of the white colonizers themselves (2007, p. 186). This system created a layered hierarchy that violently inferiorized colonized women by fusing gender with race in the operations for colonial power (Lugones, 2007, p. 201). The changes were introduced through slow, discontinuous, and heterogenous processes that effectively destroyed the two-sided complementary social structure of females and males, as well as the economic distribution that often followed this system of reciprocity. Interestingly, Lugones does mention genocide as a consequence of this process, but does not elaborate further (Lugones, 2007, p. 206). In my opinion, her contribution of gender and the concept of coloniality of power -itself derived and expanded from Anibal Quijano's work- as mutually constitutive is key to address the imposition of the gender binary as genocidal.

Nevertheless, none of the previously mentioned authors have directly connected their discussion to the concept of genocide. Allen refers explicitly to the concept, but remains ambiguous as to how she is interpreting it. Lugones only briefly implies that the imposition of gender is another face of the violence of colonization, but she does not link it to the destruction of something other than the lives of Indigenous people, thus equating genocide with mass murder. Additionally, the authors do not delve deeper into the international dynamics in which the processes of colonization were inserted, nor do they elaborate on the particularities of colonization in specific settler colonial contexts. The exception to the last point is Segato, when she briefly mentions the Yoruba resilience within the Brazilian patriarchal colonial state (Segato, 2003, p. 361). In the next lines, I will connect the previously introduced framework of analysis, that is, the violent imposition of a high-intensity, essentialist, and non-flexible heterosexist gender binary, with the experience of Indigenous populations in the Canadian settler colonial structure or “mesh”, to identify its relation to genocide.

Gender, sexuality and the mesh in Kanata

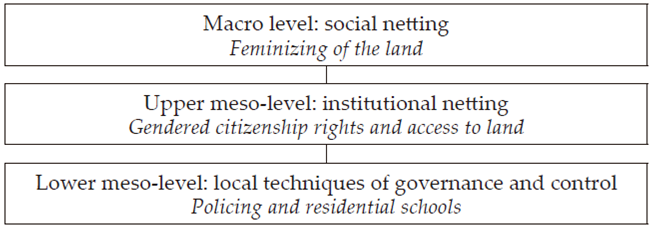

In order to illustrate the violent imposition of the coloniality of gender, I will identify specific technologies that were used for this purpose in the construction of the settler colonial state of Canada. This will entail a non-exhaustive historical account of the colonization structure that was imposed with the arrival of European settlers, and continues to be present through the institutions and laws of the modern state.5 As Adele Perry argues, gender is where the abiding bonds between dispossession and colonization become most clear (2001, p. 19). This colonization structure imposed on racialized and gendered Indigenous peoples was, however, imperfect. Woolford has proposed the term “colonial mesh” to explain the uneven spread of settler colonialism (2014). The mesh is composed by a series of nets that operate to constrain agency but are also prone to snags and openings that enable resistance (Woolford, 2014, p. 31). The first one is the social netting where the dominant visions of “the Indian problem” are negotiated; the second one is the institutional netting that integrates the operations of settler colonialism; and, the third one is the local techniques of governance and control that involve non-human actors, such as the territory (Woolford, 2014, p. 32). Thus, the Canadian case presents an example of multiple Indigenous peoples caught within a diverse web of settler colonial policies, the genocidal force of which varies across time and space as the mesh tightens or loosens (Woolford and Benvenuto, 2015, p. 379).

Source: Woolford, 2014.

Figure 1 The colonial mesh and the imposition of a high-intensity gender binary and heteropatriarchy

The social death of Indigenous peoples in Canada through the imposition of a high-intensity gender binary and heterosexuality has been achieved through every level of the mesh. At the macro level and at an initial phase, a dominant colonial vision was the feminizing of the land. As Anne McClintock described in Imperial Leather, the feminizing of the land represents a ritualistic moment, as male intruders ward off fears of narcissistic disorder by reinscribing an excess of gender hierarchy as natural (2013, p. 24). Nevertheless, the “new” lands were supposed to be “empty”, so the Indigenous peoples were dehumanized and symbolically displaced onto what McClintock calls the “anachronistic space” (2013, p. 49).6 The threatening heterogeneity of the colonies was not read as socially or geographically different from Europe and thus was equal to it, but also as unequivocally archaic. The peoples inhabiting this anachronistic space with a radically different performativity of sexuality and gender had to be contained and disciplined through the imposition of the coloniality of gender, a hierarchy that effectively placed Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA at the bottom (Lugones, 2007).

When I think about everything, I think about misplacement. For us as Aboriginal people, it's about misplacement. We were stripped of everything that we know. We've been misplaced this entire time. Urban settings such as the Eastside where my mom ended up, it's because she was misplaced, identity stripped away from her, everything, the essence of who we are as Aboriginal people taken (Rande C. as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 275).

Under this disciplining vision, colonization entails a unique form of violence exerted by instilling heteropatriarchy. Following Arvin, Tuck, and Morril's definition (2013, p. 13), heteropatriarchy is the social system in which heterosexuality and patriarchy are perceived as normal and natural, and in which other configurations are perceived as abnormal, aberrant, and abhorrent. From this perspective, heterosexuality refers less to attraction between men and women or the conditions of reproductive intercourse, and more to a kind of social formation in which coupling, procreation, and homemaking take on a particular normative shape exemplified by the nuclear family (Rifkin, 2011, p. 7). Furthermore, patriarchy rests on a rigid gender binary system, which sets the framework for targeting Indigenous peoples who do not fit within this binary model (Smith, 2010, p. 61). It has been long discussed that many Indigenous North American nations were matriarchal, positively recognized homosexuality and the existence of more than two genders, and understood gender in complementary terms rather than in terms of subordination (Allen, 2015). In other words, the heteropatriarchy as excess of gender hierarchy leads to the structural subjugation of females to males and the exclusion of the possibility of fluidity between sexual identities.

For a very long time prior to the colonial and postcolonial periods (this little blip on the trajectory of our history), Indigenous peoples brought into being and practiced a social organization that viewed gender in the same continuum, with the same sense of circularity and integral interrelations which we attached to everything in life… However, there is also a reality among all humanity, that for various, quite intimate reasons, sometimes an individual does not strictly adhere to this thing called man or woman; they feel neither completely, yet are made of both, and maybe something more (Lee Maracle as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 239).

As the colonization structure grew in complexity towards the consolidation of the nation-state, the previously described visions moved to a level of implementation: the upper and lower meso-levels. These institutionalized technologies of gendering required strict dividing lines based on European conceptions of gender and race. As such, the Indian Act of 1876 was a major step in the imposition of heteropatriarchy through the establishment of citizenship (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 249). Its early conditions were clearly gendered and racialized. They included being male, over the age of 21, literate in English or French, free of debt, and of “good moral character”; in turn, successful applicants would receive 20 hectares of reserve land in individual freehold, taken from the band's communal allotment, but would be required to surrender their “Indian Status” (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 249). With this, the settler colonial state defined and limited who could be “Indian” and who could access Indigenous lands. In other words, it entails “a two-edge genocidal sword intending to destroy the identities, cultures, and land holdings of those it defines”; furthermore, it threatens to destroy Indigenous groups and their state-defined landholding through the enforcement of Canadian law (Palmater, 2014, p. 42).

Unfortunately… in the Mi'kmaq territory, the failure of the Government of Canada to implement the 1999 Supreme Court of Canada decision of Marshall to allow access to fishery resources, especially for women, Mi'kmaw women, is one such example of historic and continued denial of economic opportunities. The denial of our resources and our rights in this country keeps Aboriginal women and Peoples in poverty. We are worth less over and over again because of governments' policies, laws, and inaction (Cheryl M. as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 249).

Moreover, by upholding the “Indian man” as the only subject entitled to the land, the Indian Act effectively reinforced the inferiorization of Indigenous women. For example, in some societies each married person held their own property, rather than holding property in common or adhering to a patriarchal scheme where only men could own land (Arvin, Tuck and Morril, 2013, p. 23). As such, the Act was not only about attempting to manage and limit access to land, but to break the matrilineality of Indigenous societies. Indian women were at risk of losing their Indian status by a variety of means, by instance through the Eurocentric patriarchal institution of marriage (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 242). If an Indian woman married a non-Indian man she would effectively cease to be considered as Indigenous. This bleeding off of Indigenous women and their children from their communities was in place until 1985, when Canada removed the presumption in favor of Indian paternity for unwed mothers (Palmater, 2014, p. 39). Yet thousands of Indigenous peoples were excluded from communal acceptance by virtue of this legislative regime, which some consider to be a form of “banishment” (Palmater, 2014, p. 40).

When we deny a woman and her children through the Indian Act legislation, you are banishing, we are banishing our family members. When you look at that in our language and in our understanding, that banishment is equivalent to capital punishment … when you banish a person they cease to exist. And in 1985, '86 I stood next to my sister who, at the age of 17, married a non-Native man and … we stood in front of the Chief and Council, and witnessed by community members in Esgenoopetitj village, and they said that my sister and my aunts ceased to exist. They were not recognized in my community (Elder Miigam'agan as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 251).

Finally, policing was a lower meso-level institution that enforced colonial control over Indigenous women and non-binary people by disrupting relationships between the genders. According to the Report, this was done by intervening in intimate aspects of women's lives, enabling sexual abuse, and through the implementation and perpetuation of particular beliefs and policies (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 253). First Nations women, in particular, were cast by the settler colonial government and society as a menace, and even as a threat to public security (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 252). Within these beliefs, First Nations women and girls were targeted because they “failed to live up to a normative standard” that imposed beliefs and expectations about womanhood that came from the patriarchal and Western settler imaginary (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 256). Failing to correctly perform “woman” also served to discredit allegations of violence by the police or by settlers.

Safety and justice and peace are just words to us. Since its inception, we've never been safe in “Canada”. The RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) was created to quash the Indian rebellions. The police were created to protect and serve the colonial state (Audrey Siegl as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 258).

In the lower meso-level of the mesh, another institution, widely acknowledged and discussed in the aforementioned Truth and Reconciliation Commission report were residential schools (TRC, 2015a). These schools mirrored early attempts at colonial religious conversion, where Christian dogma reinforced a patriarchal system that envisioned God as male and women as a secondary creation meant to keep the company of men (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 263). Residential schools were intensely separated by sex: boys and girls had different dormitories, entrances, classes, chores, recesses, and playgrounds (TRC, 2015b, p. 95). This separation had severe effects on family bonds: sisters, brothers, and female and male cousins were forbidden from interacting with each other (TRC, 2015b, p. 91). It also worked to strengthen the high-intensity binary, as boys were sometimes encouraged to continue school until they were 16 or older, while girls were often encouraged to leave school early to participate in domestic “apprenticeships” (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 263). Sexual education that could compensate for the ceremonies that marked puberty and provided elderly guidance to understand body changes was not provided (TRC, 2015b, p. 97). In addition, residential schools also entrenched the high-intensity gender binary for Two Spirit students. Finally, there is scarce documentation about queer experience in residential schools, but homosexuality was considered a sin and would have been punished by the school authorities (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 264).

I told one of the older girls, “Sister is gonna really spank me now”. I said, “I don't know, I must have cut myself down there because I'm bleeding now. My pyjamas is full of blood, and my sheets, and I was so scared. I thought this time they're gonna kill me” (Alphonsine McNeel as cited in TRC, 2015b, p. 98).

Patriarchy was also imposed through the transformation of social organization at the micro level of the mesh. Kinship is a non-family central native form of social organization that encompasses home-making and land tenure (Rifkin, 2011, p. 23). Paraphrasing Rifkin, the imposition of the rigid hierarchy, the “straightening”, occurred “within an ideological framework that takes the settler state as the axiomatic unit of political collectivity, and in this way, Indigenous sovereignty either is constrained entirely or translated into terms consistent with settler-colonial jurisdiction” (Rifkin, 2011, p. 10). Such constraint transformed the organizing structures of related individuals, not only through the institution of Western marriage, but also through a model organized around European notions of “family” (Rifkin, 2011, p. 15). The family came to condense hierarchy within unity as an organic element of historical progress, and thus became indispensable for legitimizing gendered exclusion and hierarchy within nonfamilial social forms such as nationalism under the alibi of nature (McClintock, 2013, p. 45). In other words, colonialism imposed the figure of a paternal father ruling over immature children, both within families and within the settler colonial nation. Additionally, another form of constraining the vitality of kinship was through forced sterilization programs, especially for Métis women (NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 266).

My parents, the fact that they've been through this is like… it's like they do not have a life inside of them. It's like they're… they've been treated like animals. That's how they treated my parents: “We have the right to take your children as we want.” They are taken to the boarding school and then taken to the hospital. You know, it's them who decided. It's not up to them to decide. We have lives. My parents have feelings and then they have emotions, and then I want there to be justice to that (Françoise R. as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 232).

The violent imposition of a high-intensity gender binary and heteropatriarchy destroyed the social vitality of Indigenous peoples in Canada; it was genocidal. As I illustrated previously, through the operation of the mesh, the internal relations of Indigenous groups -cultural, political, economic, educational, familial, linguistic, religious- that were determined by conceptions of gender and sexuality were destroyed or seriously degraded. There is a thread of ongoing dispossession of Indigenous people, from the determination of Indigenous subjectivity as either male or female, imposed by Western colonizers' conceptions of gender and sexuality, to the current violence that Indigenous women disproportionally face. During the settler colonization process, Indigenous subjects were first located at the bottom of a racialized hierarchy: their race and gender were constructed (Lugones, 2007). The Indigenous frameworks of gender and sexuality were radically transformed, and such a transformation entailed the destruction of the social vitality of Indigenous groups. As Jonathan Lear eloquently writes for the case of the Crow people, the experience of devastation did not come from the prospect of being physically annihilated (Lear, 2006, p. 32); it was the destruction of the conditions that upheld their way of life, that gave their lives a meaning by belonging to a genos.

After 500 years, these [colonial] ideas have not changed much. The First Nations women and girls are thought of as disposable. They are not. They are the life-givers, the storytellers, the history keepers, the prophets, and the matriarchs… The fallout of colonialism is like a fallout of a nuclear war, a winter without light (Shaun L. as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 314).

Canada is quite uncomfortable with the word “genocide.” But genocide is what has happened in Canada and the United States for First Nations people. What else can you call it when you attack and diminish a people based upon their colour of their skin, their language, their traditions, remove them from their lands, target their children, break up the family? How is that not genocide? And that's the uncomfortable truth that Canada, I believe, is on the cusp of coming to terms with. And it's going to take a lot of uncomfortable dialogue to get there (Robert C. as cited in NIMMIWG, 2019a, p. 233).

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that the imposition of a high-intensity gender binary and heteropatriarchy have been part of the genocide committed, and still ongoing, against Indigenous peoples in Kanata, or Canada. I have relied on Wolfe's conceptualization of settler colonialism as a structure, the colonial mesh described by Woolford, and the concept of genocide as social death, proposed by Card. To problematize the Western assumptions around gender and sexuality that abound in genocide studies, as well as their relation to colonialism, I relied on Oyěwùmí, Segato and Lugones. Most importantly, I have engaged in a discussion that is related to the current situation of Indigenous peoples in this settler colonial context.

The main body of this analysis has provided concrete examples of the genocidal technologies of gendering that were displayed along the colonial mesh in Canada. At the macro level, and as an ideological framework for the imposition of the coloniality of gender, the land was feminized and its inhabitants symbolically displaced. At the upper-meso level, the institutionalized technologies of citizenship and the right to own land radically altered Indigenous societies and cosmovision. Policing and residential schools are presented as examples of the technologies at the lower-meso level. The evidence to trace how these violent processes entailed the social death, or genocide, of Indigenous peoples is provided by testimonies included in the Report of the National Inquiry.

In order to build the body of evidence, I made the methodological choice of relying mainly on the previously mentioned Report. The decision is based on its availability, its geographical scope (covering all Canadian provinces and territories), and the reputation and qualifications of the body of researchers and activists that wrote it. I acknowledge that this approach has limitations, since it might overrepresent particular narratives. Other sources, such as historical archives, may prove useful for further research. Furthermore, given that my research mainly refers to First Nations experiences, locating the particular transfigurations of gender relations and sexuality within Métis and Inuit peoples may also shed light on the destructive range of colonialism, for example by highlighting the intersections with the destruction of the environment.

Colonial genocide is a radical form of imposed transformation that refigures the Indigenous “Other” as an absence in the colonized terrain (Woolford, Benvenuto and Hinton, 2014, p. 16). The imposition of a high-intensity, naturalist, and non-flexible heteropatriarchal gender binary has been crucial for this purpose. In order to better understand the power dynamics that can destroy a genos, the field of genocide studies must acknowledge that gender and sexuality are not given or universal categories; they are cultural constructions, and they must be historically located. Moreover, as Indigenous and feminist scholars have identified, they are part of a power structure aimed at disciplining bodies, molding social and economic relations, appropriating culture, and dispossessing land. They are genocidal. In this sense, both concepts entail ontological value for genocide studies beyond an analytical category.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)