Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

CONfines de relaciones internacionales y ciencia política

versión impresa ISSN 1870-3569

CONfines relacion. internaci. ciencia política vol.1 no.1 Monterrey ene./jun. 2005

Artículos

Politicians of Global Governance

Philipp Sebastian Müller*

* Escuela de Graduados en Administración Pública y Política Pública, ITESM, Campus Monterrey. Correo: philipp@itesm.mx

Abstract

Global governance offers an alternative perspective from which to imagine world order and is becoming a serious contender for explaining how we see the world and it is guiding us in legitimizing our actions in the world. Who are the politicians of global governance? What can we expect from them? What is their agenda? In order to address these questions, two things are necessary: We need to look at the structural and generative logic of global governance, identify its politics, and question the real people that are the politicians of global governance that have real-world impacts in a world order conceptualized as global governance.

I. Introduction

Global governance offers an alternative perspective from which to imagine world order. As it becomes a serious contender for explaining how we see the world, it is guiding us in legitimizing our actions in the world. When in 1998 Louis Pauly posed the provocative question, "Who elected the Bankers?" the thrust of the inquiry was to challenge the emerging structure of global governance. Since then the emergent structure of global governance has gained increasing legitimacy as a mainstream conception of world order, so the question needs to be amended to how we can hold the politicians of global governance accountable in order to salvage at least some of the original critical spirit. In a similar vein, David Kennedy (2001) argues in his article "The Politics of the Invisible College" that it is necessary to move beyond debates about the desirability of global governance, and that we should accept the distributive role of global governance and focus on its outcomes, whether progressive or regressive. He states that although international policy professionals often perceive themselves to be intervening neutrally, their real role is one of government.

This means that as responsible social scientists we need to ask new questions: Who are the politicians of global governance? What can we expect from them? What is their agenda? As policy advisors or theorists that believe that academic writing does not only describe, explain, and predict but that it actually impacts social life we need to outline how individuals or groups affected by acts of the politicians of global governance can hold them accountable.

In order to address these questions, two things are necessary: We need to look at the structural and generative logic of global governance, identify its politics, and develop ways of questioning the real people that a re the politicians of global governance. The following paper is a first sketch of such an attempt. It does not aim to describe, explain, and predict from the neutral realm of the academic observer, but outline the types of questions that need to be asked of politicians in a world imagined as global governance. In order to do this, the paper describes how the vocabulary of global governance is used (II), what the grammatical structure of this vocabulary allows us to say (III), what it means to ask questions about the politics of global governance (IV), and how to ask questions about the politicians of global governance (V).

II. What is Global Governance?

Global governance offers a functionalistic vocabulary that can offer solutions to problems conceived as coordination or technical problems but is blind to international politics confined by international law. It is no longer a utopian project of UN bureaucrats who imagine that global issues can be solved by problem-oriented, multi-sectoral networks. We encounter global governance, or more precisely the descriptive vocabulary and legitimizing arguments of the global governance system of thinking and doing, every day in our lives. It comes natural to us that it makes sense to build institutions through combined efforts by the private and the public sector such as the World Commission on Dams or the "Roll Back Malaria" campaign. We accept civil society organizations as service providers and transformational agents in our domestic politics. When local civil society organizations are linked to global ideas or organizations, their clout in local politics increases - because they can rely on the legitimacy of the global. We take seriously global gatherings that legitimize themselves recursively by meeting, and achieving presence in the global media such as the World Economic Forum, the World Social Forum, or the multi-sectoral UN-summits on any issue from women's rights to information technology. Therefore, the system of thinking and doing that we call global governance is here and it is here to stay.

Just as every book on the international realm from 1991 to 2000 has referred to the end of the cold war as a historical starting point, books in the 21st century refer to globalization, i.e. the transformative change that the international system is experiencing, as a starting point (Fuchs and Kratochwil, 2002). Transformative change has thus created a need to find a new framework or vocabulary to describe how the world we inhabit is governed.

Global governance addresses this need. It is, of course, not the only term that competes to imagine world order. For IR-conservationists, there still is the notion of the "Westphalian state system" or of "Uni-, Bi-, and Multipolarity"; and frameworks such as "Global Anarchical Society" (Bull, 1977), "Neo-medievalism" (Friedrichs, 2001), "Empire" (Hardt and Negri, 2001), and Donald Rumsfeld's dictum of the "Coalitions of the Willing" are vying for supremacy.

In the literature, three strategies to categorize global governance have emerged. The first offers a non-definition consisting of the denial that something like global governance exists at all, the classical position of mainstream international relations; the second is to offer a positive definition that often very idealistically assumes that a new form of managing global affairs has developed that can be characterized through specific actors, instruments or practices. The third is by juxtaposing global governance to a term with which we feel more comfortable.

II. a. Strategy of Denial

Mainstream international relations theory continues to have difficulties with global governance because of its foundational conceptualization of the international system as an anarchic realm (Jahn, 2000). Thus, for many, governance is nothing new per se but merely a continuation of the interdependence literature of the 1 970s or of the discussion about regimes in the 1980s. Given the strongly state-centric focus of international relations theory (especially regime theory) this position makes sense (Hasenclever et al., 1997). Even those who have started to take other actors more seriously do not conceptualize them as independent agents, but still define their roles in relation to the nation-state or to the intergovernmental system of the UN (for example Messner and Nuscheler, 1996).1 Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the strategy of denial has again gained influence. Thus, such a view can be crowned by success, as long as scholars and policy makers are able to persuade the rest of the world that only a security-centered perspective resonates with the 'brute' facts of international life.2

II. b. Strategy of Finding a Positive Definition

In total contrast to the strategy of denial is the attempt to catch all new practices that have developed within the global realm in one positive definition. The most prominent example of such an exercise is the definition of the Commission on Global Governance, which stated that global governance is "the sum of the many ways individuals and institutions, public and private, manage their common affairs. It is a continuing process through which conflicting or diverse interests may be accommodated and co-operative action may be taken" (1995, 2f). This all-inclusive perspective gave respectability to global governance studies as an academic field and a policy area; however, because of its over-inclusiveness it cannot suggest research avenues, operationalizable hypotheses, or policy recommendations.

A scholarly, more ambitious project is James Rosenau's analytic attempt to focus on "systems of rule at all levels of authority" (1995: 13) and on "spheres of authority" which are able to set norms on various levels. For Rosenau, global governance thus compromises "all the structures and processes necessary to maintaining a modicum of public order and movement toward the realization of collective goals at every level of community around the world" (1997: 367). Such a broad understanding of the term allows us to account for the evolution of new instances and forms of governing but the price to pay is that the definition itself becomes so open that it is bound for theoretical over-stretch.

Another way to define global governance in a positive strategy is to use the term only in relation to the empirical fact that actors other than governments have become important agents on the international scene. Because of this, a large portion of the debate over global governance is dedicated to conceptualizing which actors are influential in international life and how they exert their influence and legitimize it in relation to their principals. Sub-state groups or regions (Ohmae, 1996), supra-national organizations, intergovernmental groups, transnational corporations (TNCs) and their associations, and individual non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Higgott et al., 2001) have all been identified as relevant actors. While these actor-centered approaches have convincingly shown that new actors have indeed become relevant agents in global affairs, they nevertheless could not capture in a systematic way what positively defines global governance as a practice.

II. c. Strategy of Defining Global Governance through Juxtaposition

Because many scholars dismiss defining global governance in positive terms as fruitless, some researchers have taken to juxtaposing it to a known and familiar term. Examples are seeing global governance as not government or the idea of global governance as a political answer to economic globalization.

One early notion of defining global governance in juxtaposition comes from Rosenau and Czempiel, who speak of Governance Without Government (Rosenau and Czempiel, 1 992). Similarly, Lawrence Finkelstein states that global governance is "governing, without sovereign authority, relationships that transcend national frontiers. Global governance is doing internationally what governments do at home" (Finkelstein, 1995: 369). Such a perspective is, however, problematized by comparative political scientists who discuss governance mechanisms as being part of the transformation of the state itself (Pierre, 2000). Thus, if one separates governance and government too strictly, one assumes that the international realm itself is not connected to the domestic one. However, global governance is not only a multi-level game that sometimes includes domestic institutions and sometimes does not; on the contrary, global governance very often fuses both realms in such ways that they become one.

The second juxtaposition is to argue that global governance is the political answer to an economically determined process of globalization (for example Messner, 2000: 3f). Most NGOs also use the term to offer an alternative to the neoliberal Zeitgeist:

In such a situation the concept of global governance presents itself. It is combined with the demand to resolve the problems of a neoliberal globalization. The concept is presented as a progressive alternative to neoliberalism (Brand et al., 2000: 13)*

This is of no surprise as the process of globalization has raised doubts in how far a more internationalized system is of value for individuals and beneficial for the general public as a whole. The argument is that the compromise of "embedded liberalism" (Ruggie, 1983) in which the increase of international trade flows was accompanied by protective measures to ensure social stability has been abandoned and no substitute seems yet at hand. Opponents of globalization such as ATTAC (www.attac.org) argue that global governance has the chance to become the political alternative to the economistic hegemonic project of globalization that oppresses the underprivileged classes both in the political North and South. They, as well as many parts of the established social-democratic left, thus argue for mechanisms that would decrease economic inequality on a global scale. On the academic side, doubts about the legitimacy of globalization had been raised at a very early stage (Messner and Nuscheler, 1996; Altvater and Mahnkopf, 1996), but until the first organized resistance at Seattle, Gothenburg, and Genoa, neither public officials nor academic institutions had paid much attention to the developing resistance movement (Klein, 2001). As sympathetic as this usage might be, by juxtaposing political global governance and economic globalization, the political aspects of both are lost.

Globalization is not the economically determined fate of humankind, but instead has, for example, been advanced by states even in the critical case of international financial markets (Helleiner, 1994). Similarly, global governance is also much more than the 'good politics' that heals the bad effects of globalization and thus has often unintended, and sometimes very detrimental consequences. In short, important political developments are missed when one overestimates either globalization as the bad or global governance as the good. In the end, both processes are depoliticized. If we now take a step back from the term global governance and focus on how the concept is used, we can dissolve our call for definitional clarity.3

This type of argumentative move is necessary, for two reasons: Firstly, the vocabulary of global governance is unable to internally discuss political issues. Secondly, the concept offers only output-legitimated technocratic problem-solving mechanisms. This is important because acts of definition are political acts, especially in times of transformative change. Any definition demarcates between just and unjust claims, legitimizes types of authority, and includes and excludes actors from political participation. Only by foregrounding these questions that are usually hidden can we uncover and demarcate their politics. In times of transformative change, it is exactly on the level of defining the rights of participation where the politics of a new political idea takes place. The underlying diversity can neither be ignored nor can it be subdued through introducing a 'right' definition, but should be fostered and its political aspects demarcated. During times of transformative change, when the world changes in a way that the concepts we have to describe it lose their descriptive power, such a critical approach allows us to describe this process of transformation in basic understandings of how societies and collectivities function.

Thus, a perspective focusing on the academic discourse alone is not enough to actually access the politics that take place on this level. Only (a) the acceptance that theory influences policy, and (b) the inclusion into the discourse of policy makers, who actually shape the world by imagining it and acting in it, allow us meaningful access to the politics of global governance. This is especially salient in this case because international relations is an elitist and abstract practice both on the policy and theory levels, allowing individuals to play a large role in imagining the world we think about and act within (Müller, 2003). We reify and anthropomorphize corporate actors, such as states and supranational organizations, and consequently our expectations about appropriate behavior are very much dependent on what characteristics we ascribe to these 'non-natural' persons.

Therefore counter-intuitively, for the very specific type of problems global governance poses, real-world relevance is not acquired by an empirical research design, but by a critical reflection of the vocabulary we use to describe and explain in order to achieve a better understanding of what we are actually saying and doing when we talk about and practice global governance. As academics and policy makers we must therefore focus on global governance as a heuristic tool and a political project. This is a moment where political theory has policy relevance, because it takes its role in constructing the world seriously.

III. The Generative Logic of Global Governance

Why has global governance become such a strong contender as a system of thinking and doing when we want to explain and imagine world order? What is global governance, and how do we use the concept? The term "system of thinking and doing" is a shortcut for the idea that we use a certain vocabulary to describe/ explain/predict a world and at the same time to use this vocabulary to legitimize our actions inside the world.4 To describe/explain/predict is to take the role of an outside observer, to legitimize actions inside the world is to make arguments by referring to an intersubjectively accepted body of truths (communicative rationality) or by referring to transcendental or procedural modes of authority. The term allows us to reflect on worlds in which we need to deal with the recursive relationship between thinking and doing and outlines the grammar of enquiring into these types of worlds:5 it reminds us that our methods of validation that we use when a distinction between observer and the observed exists are not applicable.

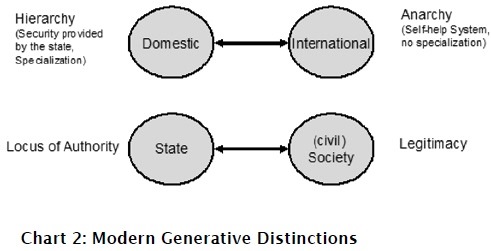

World order is the term we use to describe (inter)social relations. By focusing on the logic of world order, we can demarcate different world orders spatially and historically. Different logics at work allow us to describe the (generative) rules that describe/explain modes of legitimation of actions in different systems of thinking and doing and allow us to demarcate them from other worlds. World orders can be imagined on the continuum from spontaneous interactions, such as the market to transcendentally-legitimized hierarchical systems (Hardt and Negri, 2001). This can be better understood if placed in a historical framework as is shown in the following graphic:

If one is interested in contemplating the modern state system in terms of its logic, then one can make a surprisingly simple argument (that has been repeated often, e.g. Osiander, 1994; Walker 1995; Kratochwil, 1989; Friedrichs, 2001; Wendt,1999, etc.): The figure of sovereignty with its binary distinctions of the domestic/international and state/society has a generative function that has structured world order (Bartelson, 2001). The following graphic allows us to identify the two distinctions that are generative for great parts of the modern political discourse both on the theory and the policy levels:

Global governance then is the world order that goes beyond these institutions. It includes, however, not only the dissolution of the boundaries, but a positive construction of a system of thinking and doing out of different original distinctions.6

There are three historical forces that are confronting us with the need to reconceptualize world order: The emergence of global issues, the contestation of the legitimacy of political entities, and changes in how we think and do things in the world are forces that are leading to a re-evaluation of how to imagine world order. The first historical force consists of events in our "material" world, such as global warming, the integration of the global financial and trade flows, and cultural globalization that have led to the emergence of the idea of global issues as legitimate arguments in policy debates on domestic, international, and global levels (Kaul et al., 1999). The idea of global issues is being circumscribed by a number terms such as globalization, global commons, global public goods, and global public bads. The second historical force is the crisis of modernity that comes to bear on our understanding of the nation-state both internally (blurring of the boundary between private and public spheres) and externally (blurring of the boundary between the inside and the outside).

And the third is a shift in our understanding of instrumental rationality, i.e. how we get things done in the world, from institutional to functional solutions of problems. By shift of our understanding of instrumental rationality, I mean that a shift can be observed from the idea of dealing with problems through ex ante legitimated institutions, where legitimation of any problem solution is achieved by referring to mechanisms of procedural justice (Rawls, 1971) to an understanding where problems legitimize the institutions that are built around them.

These three discrete forces together are presenting us with the problem of governing the post-nation-state world. One world order framework that seems to be able to address these three forces is global governance. Therefore, as a political idea, global governance has the chance to supersede other understandings of world order, such as the modern nation state system, world government, or 'coalitions of the willing.' In academia, the concept is emerging as an important framework to imagine the global realm, and for policy makers, global governance is a political project and an emerging background condition.

In the following matrix I relate our understanding of instrumental rationality to the principles of organizing international/world systems. We can then distinguish between different worlds that have different capabilities to deal with our third force, namely the emergence of global issues.

In short, global governance offers an alternative perspective from which to imagine world order and is becoming a serious contender for explaining how we see the world and it is guiding us in acting in the world. The ability to think and act on global issues, however, comes at a cost. The legitimacy of issue-specific institutions can only come from the success or effectiveness of the problem-solving mechanism.

IV. Politics of Global Governance

If we want to ask about the politics or political ramifications of a concept or vocabulary we need to roughly say what we mean when we say politics. Asking about the politics of global governance entails asking about how authority is ascribed and legitimated. So we can roughly say that politics is the vocabulary that deals with questions that are described as questions of choice for collectivities (Bartelson, 2001; Anderson, 1983). It can be circumscribed by the terms community and authority that can be ostensibly related to the questions "Who is member?" (the question of community or identity) and "who gets to decide?" (the question of authority), as is shown in the following graphic.

Questioning the politics of world order allows us to ask about who gets, what, when, and how and how expectations are structured in a world (Lasswell, 1936). Then a framework to think politics is to distinguish between different aspects of politics. It must be able to address (a) who is a member, what questions we may talk about, and what are the ground rules, (b) how conflicts between competing interpretations of collectivity are actually solved inside the accepted system of rules, and (c) instances of partial compliance, the sometimes unfair haggling cases that fall outside the accepted system of rules. This can be described in the following framework:

Theoretically, in global governance, we should mainly encounter instances of parapolitical arguments and some efforts at meta-politicking, because, as shown in Chart 3, we are dealing with a vocabulary that allows us to speak of the efficacy of a specific project, but not so well of questions of accountability (Kennedy, 2001). However, we need to be prepared to find a way of asking questions because global governance as a (functional) vocabulary to describe, explain, imagine, prescribe, and legitimize global governance is here to stay. And it is not difficult: We need to take a critical stance, assign responsibility to the actors that are actually acting in global governance and ask about them, the politicians of global governance.

V. Foregrounding Accountability Questions: Background-Checking Horst Kohler

Assigning responsibility to individuals for political acts is a theoretically challenging project. However, following Max Weber's seminal Politics as Vocation (1994) any approach to politics should make room for the individuals actually imagining collectivity or making authoritative decisions. And that forces us to ask some very simple common sense questions of actors we identify as politicians of global governance. We need to identify them, understand them, and assign responsibility to them, and hold them accountable.

We are used to holding accountable democratically elected representatives and even non-elected heads of state, however, we are not yet good at dealing with a new breed of politicians that understand themselves as neutral professionals. In order to foreground issues that we have to deal with if we want to understand, assign responsibility, and hold accountable the politicians of global governance, I will read the official IMF biography of Horst Köhler, who was elected President of Germany on May 23, 2004.7 This type of approach does not test any hypothesis - it is not even a plausibility probe. It does allow us to reflect, however, the sensibilities we need to develop if we want to hold politicians of global governance accountable. Horst Köhler was not randomly selected and he is not a hard case (Eckstein, 1975), but it is interesting to focus on him because he is someone who has played an important role in governing the global as the director of the International Monetary Fund and has now crossed into the camp of the elected representatives as the president of Germany.

Horst Köhler assumed office as Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund on May 1, 2000. This followed his unanimous selection by the Executive Board of the IMF, on March 23, 2000, to serve as Managing Director and Chairman of the Executive Board. He resigned on March 4, 2004, following his nomination for the position of President of the Federal Republic of Germany.

This is the first time in the history of Germany that a president was elected who had not lived in the country for several years before being elected. Interesting is the wording "nomination for the position of President of the Federal Republic of Germany," because even though the parties that nominated him as candidate had the majority in the electoral college, there was a democratic election process between the nomination for the candidature and his taking office. This can be read as an oversight, or as a slip into postmodern governmental functionalism.

Mr. Köhler earned a doctorate in economics and political sciences from the University of Tubingen, where he was a scientific research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economic Research from 1969 to 1976. After completing his education, he held various positions in Germany's Ministries of Economics and Finance between 1976 and 1989.

As would be expected of a technocratic functionalist, he did his Ph.D. in economics and worked as a public servant.

Prior to taking up his position at the IMF, Mr. Kohler was the President of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, a post to which he was appointed in September 1998. He was President of the German Savings Bank Association from 1993 to 1998. From 1990 to 1993, he served as Germany's Deputy Minister of Finance, being responsible for international financial and monetary relations. During this time, he led negotiations on behalf of the German government on the agreement that became the Maastricht treaty on European Economic and Monetary Union, was closely involved in the process of German unification, and held the position of Deputy Governor for Germany at the World Bank. He was personal representative ("sherpa") of the Federal Chancellor in the preparation of the Group of Seven Economic Summits in Houston (1990), London (1991), Munich (1992), and Tokyo (1993).

His role as a technocrat was what made him a potential compromise candidate for the coalition parties (CDU/CSU and FDP). His work in the private sector from 1993 to 1998 made him electable for the Free Democrats (FDP).

Mr. Köhler was the eighth Managing Director of the IMF. He directly succeeded Michel Camdessus, who retired from the IMF on February 14, 2000. Previous Managing Directors were Camille Gutt (Belgium, 1946-51), Ivar Rooth (Sweden, 1951-56), Per Jacobsson (Sweden, 1956-63), Pierre-Paul Schweitzer (France, 1963-73), H. Johannes Witteveen (Netherlands, 1973-78), and Jacques de Larosiere (France, 1978-87).

Mr. Köhler was born in Skierbieszow, Poland on February 22, 1943. A German national, he is married to Eva Kohler and has two children.

In the German debate before his election, the institutional-vs.-functionalist divide can be observed clearly. The institutional (or nation state) arguments are that Horst Kohler is not a politician, that he has not been living on German territory, and that as an economist, he cannot relate to people. The functionalist (or global governance) arguments are that his global perspective will help Germany to globalize, that his economic perspective will functionalize (or depoliticize) the discourse on globalization, and that his background in the public and private sector will lead to better multi-sectoral cooperation. In his inaugural address on July 1, 2004, titled "We Can Make So Much Happen Here,"8 he focused on the role of Germany in a globalizing world. He specifically introduced the term globalization in the fifth sentence of the opening statement, thanking the former president for a conversation on the topic. His analysis of the situation in Germany was of a state that has great resources, yet that needs to increase its competitiveness. The solutions he sketched in the inaugural speech were very (neo)liberal suggestions of personal improvement. Comparing him to his predecessor in the office of the presidency, Johannes Rau (Social Democrat, SPD), underlines this change in the political culture. Johannes Rau had been in German politics all of his adult life, he had never left the country for extended periods of time, and had never worked for the private sector. His political beliefs were formed by the protestant church and he was jokingly referred to as "Brother Johannes."

V. Conclusion: What Does This All Mean?

The paper has sketched an approach of how to ask questions about the politicians of global governance. It has not given a general answer and does not aspire to do so - it most definitely does not even want to draw conclusions about the new German president. It did, however, outline how such questions can be asked. And it has shown that this is necessary in a time when world order can be described as global governance.

I argued that we are in times of transformative change, where emerging conceptions of world order are challenging our traditional conceptions of international relations. There are historical forces confronting us with the need to reconceptualize world order: the emergence of global issues (e. g. global warming, global pandemics, global terrorism), the contestation of the legitimacy of political entities (e. g. NGOs, TNCs, Public-Private-Partnerships), and changes in how we think and do things in the world (e. g. project-oriented work, flat hierarchies, output-legitimation) are leading to a re-evaluation of how to imagine world order. Global governance is today the main vocabulary that is used to describe how we manage our worlds. I analyzed the grammatical structure of this vocabulary and identified its functionalistic bias and its corresponding difficulty to talk about issues of politics - in the jargon of global governance we can ask para-political and some meta-political questions. However, to ask simple political questions, we need to leave the discourse and take a critical stance. This means that it is difficult for us to hold accountable the individuals that make political decisions in a world legitimized by global governance. Therefore, we as observers of global governance have the responsibility to sketch ways of how these types of questions can be asked. I used the biography of Horst Kohler as a playful tool to identify the types of questions we need to ask of the politicians of global governance.

These questions need to be asked of anybody who plays a role in governing the global sphere, and because the global is everywhere, we need to also ask those who are governing the local. It is an important task at a time when distributive politics are hidden behind technocratic vocabularies and functionalistic ideologies of global governance.

Bibliography

Altvater, E. and Mahnkopf, B. (1996). Grenzen der Globalisierung. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot. [ Links ]

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso. [ Links ]

Bartelson, J. (1995). A Genealogy of Sovereignty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

---------- (2001). A Critique of the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bull, H. (1977). The Anarchical Society. A Study of Order in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Commission for Global Governance (1995). Our Global Neighborhood. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cutler, C. A. , Haufler, V. and Porter, T. (1999). Private Authority and International Affairs. In Clarie A. Cutler and Virginia Haufler, Tony Porter (eds.): Private Authority and International Affairs. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. 3-28. [ Links ]

Dirk, M. and Nuscheler, F. (1996): "Global Governance, Organisationselemente und Saulen einer Welt-ordnungspolitik". In Dirk M. and Franz N. (eds.). Weltkonferenzen und Weltberichte. Bonn. pp. 12-36. [ Links ]

Eckstein, H. (1975). Case Study and Theory in Political Science In Smelser, N. (Ed.). Handbook of Sociology. Newburg (CA): Sage. [ Links ]

Finkelstein, L. (1995). What is Global Governance. In Global Governance, 3,1. pp. 367-372. [ Links ]

Friedrichs, J. (2001). The Meaning of New Medievalism. In European Journal of International Relations, 7,4. pp. 475-502. [ Links ]

Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2001). Empire. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Hasenclever, A., Majer, P. and Rittberger, P. (1997). Theories of International Regimes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Haufler, V. (1993). Crossing the Boundary between Public and Private. In Volker R. (ed.). Regime Theory and International Relations. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Held, D. (1995). International Law and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance. Oxford: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Helleiner, E. (1994). States and the Reemergence of Global Finance. From Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Higgot, R. et al. (2000). Non Sate Actors and Authority in the Global System. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jahn, B. (2000). The Cultural Construction of International Relations: The Invention of the State of Nature. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Kaul, I. (2000). Macht oder Ohnmacht der Politik? Global Governance als Antwort auf Globalisierung. Stellungnahme zur öffentlichen Anhörung der Enquete-Kommission "Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft - Herausforderungen und Antworten" des Deutschen Bundestages. [ Links ]

----------, Grunberg, I. and Stern, M. (1999). Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kennedy, D. (2001). The Politics of the Invisible College: International Governance and the Politics of Expertise. European Human Rights Law Review, 5, pp.463-598. [ Links ]

Klein, N. (2001). No logo. Der Kampf der Global Players um Marktmacht; ein Spiel mit Verliern und wenigen Gewinnern. 3rd ed. München: Riemann. [ Links ]

Kratochwil, F. (1997). International Organization: Globalization and the Disappearance to Publics. In Jin-Young Chung (ed.). Global Governance. Seoul: Sejong, pp. 71-123. [ Links ]

---------- (2002). Globalization: What It Is and What It Is Not. Some critical reflections on the discursive formations dealing with transformative change. In Fuchs, D. and Friedrich, K. (eds). Transformative Change and Global Order. Reflections on Theory and Practice. Munster: Lit. [ Links ]

Lasswell, H. (1950). Politics: Who Gets What, When, and How. New York: P. Smith, [1936] [ Links ]

Messner, D. (2000). Architektur der Weltordnung. Strategien zur Losung globaler Probleme. Vortragsbegleitende Unterlage zur Anhörung der Enquete-Kommission "Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft - Herausforderungen und Antworten" des Deutschen Bundestages. [ Links ]

Müller, P. S. (2003). Unearthing the Politics of Globalization. Hamburg: LIT. [ Links ]

Ohmae, K. (1996). End of the Nation State: The Rise of Regional Economies. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Osiander, A. (1994). The States System of Europe 1640-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pauly, L. W. (1998). Who Elected the Bankers: Surveillance and Control in World Economy. Cornell: Cornell Univ Press. [ Links ]

Pierre, J. (2000). Introduction: Understanding Governance. In Jon Pierre (ed.). Debating Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

---------- and B. Peters, G. (2000). The New Governance: States, Markets, and Networks. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Rawls, J. (1999). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [ Links ]

Rosenau, J. (1995). Governance in the Twenty-First Century. In Global Governance,1,1. 13-43. [ Links ]

---------- (1997). Along the domestic-foreign Frontier. Exploring Governance in a Turbulent World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

---------- (2000). Change, Complexity, and Governance in a Globalizing Space. In Jon Pierre (ed.).Debating Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 167-200. [ Links ]

---------- and Czempiel, E. (eds.) (1992). Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ruggie, J. (1983). International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Postwar Economic Order. In Krasner, S. (ed.). International Regimes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

---------- (1993) Multilateralism Matters. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Walker, R.B.J. (1993). Inside/Outside: International Relations as Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

---------- (1994). Politics as Vocation, In Weber, M. Political Writings (edited [and translated] by Peter Lassman and Ronald Speirs.). Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wendt, A. (1999). Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

1 It is therefore no surprise that James Rosenau — an early and vivid contributor to the debate — has rather pessimistically concluded that the discussion on global governance has not really abandoned the notion of an anarchic international system and has not yet contributed to a global political order (Rosenau, 2000).

2 There are, of course, many doubts in order to take 9/11 and what happened afterwards as a 'validation' of a realist reading of global politics - after all the four airplanes were used by a truly transnational movement of nonstate agents. Nevertheless, one has to concede that at least the US government has acted within a realist perspective: Al Qaida was located primarily in the state of Afghanistan and not transnationally, as this would have been hard to sell to Pakistan or Saudi Arabia.

* Author's translation.

3 For a theoretical discussion of such a strategy see Kratochwil, 2002.

4 The word world is understood here as that part of the universe that is interesting for an observer or actor, or "The sphere within which one's interests are bound up or one's activities find scope; (one's) sphere of action or thought; the 'realm' within which one moves or lives." (Oxford English Dictionary. Definition 10).

5 Grammar, understood here in the late Wittgensteinian sense, is constituted by all the linguistic rules that determine the sense of an expression (Hacker, 1986: 179-92).

6 It is not clear if Jens Bartelson would agree. His main argument in the Critique of the State (2001) is that we do not have the vocabulary to think beyond the nation state, because of the critical stance we are taking in order to develop this vocabulary. He argues that any critical theory cannot play a constructive role beyond the deconstruction of a prior system of thinking and doing.

7 His official bibliography is available at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/omd/bios/hk.htm (accessed May 1, 2004).

8 http://eng.bundespraesident.de/frameset/index.jsp

Información sobre el autor

Philipp S. Müller es Profesor de Relaciones Internacionales en la Escuela de Graduados en Administración y Políticas Públicas del Tecnológico de Monterrey. Hasta el 2003, era Investigador Senior Asociado del German Institute for Internationl and Security Affairs en Berlín. Doctor en Relaciones Internacionales, Derecho Internacional, y Filosofía. En su investigación, se enfoca en cuestiones de gobernancia global, la politización de la globalización, y las políticas del Internet. Es co-fundador del sitio de Internet de investigación y política Critical Perspectives on Global Governance (www.cpogg.org).