Introduction

Former U.S. President Donald J. Trump famously called the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) the “worst trade agreement ever” during his 2016 campaign. After he threatened to withdraw the United States from NAFTA in April 2017, his more rational advisors coaxed him into renegotiating it instead. Following a lengthy and often tumultuous negotiation process, the newly baptized United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) went into effect on July 1, 2020. Consistent with Trump’s “anti-globalism,” any mention of “North America” or “free trade” was excised from the title; each country was free to put itself first.

Hence, the new agreement is known as CUSMA in Canada in English, ACÉUM in Canada in French, and T-MEC in Mexico.1 But these convenient rearrangements of the order of the countries’ names cannot conceal the fact that the rewrite of NAFTA was largely driven by theT rump administration’s effort to inject its “America First” agenda into a trade agreement.

The Trump administration believed that NAFTA had given too much encouragement to foreign investment in Mexico and the offshoring of U.S. jobs there. Former U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Robert Lighthizer, who led the NAFTA renegotiation, designed a strategy for attempting to reverse the outflows of foreign investment and offshoring of jobs by writing various kinds of obstacles and disincentives for such activities into the new agreement (Miller, 2018; Ciuriak, 2019). Lighthizer pushed for three kinds of measures that he hoped would achieve the administration’s objectives: instituting stronger regional (North American) and national (U.S.) content rules for automobiles and other industries; fostering greater uncertainty about the future of the agreement and the protection of foreign investors’ property rights in Mexico; and strengthening the enforcement of labor rights in that country. In some of these areas, Lighthizer won allies from groups that did not normally support Trump administration policies, such as labor unions and environmental activists. To win the votes of Democrats in the U.S. Congress, the USTR and the Mexican government agreed to modify the USMCA (as originally negotiated) to strengthen the enforcement of labor rights and eliminate extended patent protection for biologics. As a result, the USMCA became the only major policy initiative that won broad bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress during Trump’s term in office.

The entire negotiation of USMCA was carried out under continual threats by Trump, including not only a possible U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA, but also a 35-percent tariff on all imports from Mexico, a 25-percent “national security” tariff on automobiles, and closure of the U.S.-Mexican border.2 Nevertheless, Canada and Mexico had little choice but to participate and put the best face on “modernizing NAFTA,” given the importance of the U.S. trade relationship for both of their economies.3 For the Mexican and Canadian governments, the main objective was simply to limit the damage and to ensure-as much as possible-the continuation of largely tariff-free trade in North America. The USMCA was not an ideal rewrite of NAFTA for Canada or Mexico, but rather the best “deal” they could salvage under the circumstances.

Leaving its bullying tactics aside, however, the Trump administration was not entirely wrong in its diagnosis. Many studies have found that NAFTA-along with other trade agreements, the rise of China, and globalization more broadly- contributed to some degree to the decline of manufacturing employment and a more unequal distribution of income in the United States. The relevant policy question, however, is whether the kinds of provisions that Trump’s negotiators sought in the revised NAFTA can somehow turn the clock back and recreate the U.S. industrial and wage structure of decades past, or even induce a more modest return of manufacturing jobs and increase in wages for U.S. workers.

This article will assess the new provisions in USMCA that the Trump administration hoped would discourage foreign investment in Mexico and promote a revival of U.S. manufacturing. To establish a baseline for this assessment, the next section will review the evolution of North American trade and its impact on the member economies since NAFTA went into effect in 1994. The following section will analyze the changes in manufacturing output and employment in the United States and Mexico and the evolution of Mexico’s real exchange rate (RER) prior to the NAFTA renegotiation. The subsequent section will discuss the provisions in USMCA that were most central to the Trump administration’s objectives. Given this focus, the article will not attempt to provide a comprehensive account of all new provisions in the agreement.4 Finally, the concluding section argues that-even though it is too soon to reach a definitive verdict, and even though USMCA does contain some positive features-this new agreement is unlikely to achieve the Trump administration’s main goals.

Economic Impact of NAFTA: A Brief Retrospective

The value of total regional trade in North America increased almost four-fold, from US$ 290 billion in 1993 to over US$ 1.1 trillion in 2017 (Burfisher et al., 2019, p. 4). However, such data can give an exaggerated impression of the quantitative impact of NAFTA for four reasons: the use of nominal rather than real values of exports and imports; the measurement of each country’s exports by gross value rather than value added; the double-counting of imported intermediate goods used in export production; and the failure to consider how much North American trade would have grown in the absence of NAFTA. Econometric estimates of the impact of NAFTA tariff reductions on regional trade suggest a boost on the order of about 25 to 100 percent (Romalis, 2007; Caliendo and Parro, 2015), that is, no more than a doubling-which, of course, is still a very substantial increase.5 Artecona and Perrotti (2021: 18-19) observe that Mexico had the largest cumulative market share gain in the United States (16 percentage points) of any Latin American nation between 2002 and 2018, a performance that can plausibly be attributed (at least in part) to NAFTA advantages.6 Nevertheless, North American trade has diminished as a share of total world trade in the post- NAFTA era, and all three countries diversified their import sources away from NAFTA partners (especially toward China) after 2001 (Blecker, 2014, 2019).

However much regional trade has grown, NAFTA and associated neo-liberal reforms in the 1990s did not bring about the hoped-for increase in Mexico’s long-term growth. Following the peso crisis of 1994-1995, Mexico had a brief boom in the 19962000 period, but from 2001 to 2021 its real GDP grew at only a 1.6-percent average annual rate (0.3 percent per year in per capita terms), much more slowly than the 5.2-percent average (3.6 percent in per capita terms) for all developing and emerging market nations during that period.7 As a result, Mexico’s per capita income and labor productivity failed to converged with U.S. levels during the post-NAFTA period (Blecker and Esquivel, 2013; Blecker, 2016; Blecker, Moreno-Brid, and Salat, 2021). Explanations for why the gains in Mexican exports did not translate into more rapid overall growth are found in a large literature, detailed discussion of which would be beyond the scope of this article (for various points of view, see Moreno-Brid and Ros, 2009; Hanson, 2010; Ros Bosch, 2013; Hernandez-Trillo, 2018; Levy, 2018; López, 2018; González, 2019; Blecker, 2021; Huerta, 2021), but clearly a free trade agreement with the United States did not prove to be the panacea that the Mexican government originally claimed it would be. However, Mexico is not alone in experiencing anemic growth in the last two decades: all three NAFTA members have had average annual GDP growth rates of under 2 percent per year since 2001.8

Conventional estimates show extremely small (and not necessarily positive) net welfare gains from the tariff reductions in NAFTA (Romalis, 2007; Caliendo and Parro, 2015). For Mexico, these estimates range from a net loss of 0.3 percent of GDP (mainly caused by trade diversion) to a net gain of 1.3 percent (taking into account gains from trade in intermediate goods). For Canada and the United States, the estimated net welfare effects found in these same studies are minuscule -generally less than 0.1 percent of GDP in either direction (positive or negative). Productivity has grown strongly in Mexico’s modern firms and export sectors, but average productivity growth has been held down by low and stagnant -and even falling- productivity in small, domestically oriented, and informal firms (Bolio et al., 2014; Levy, 2018). Escaith (2021) cites evidence from Díaz Bautista (2017) and others who have found positive effects of Mexico’s trade opening on productivity in export-oriented manufacturing sectors, but concludes that the gains were concentrated in the northern and west-central regions of the country.

Trade liberalization in North America has also had important distributional consequences and imposed significant adjustment costs, although in the U.S. case these effects were much smaller than the later impact of what Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2016) have called the “China shock.” Hakobyan and McLaren (2016) found that NAFTA tariff reductions resulted in significant wage losses for U.S. workers in the local areas most impacted by those tariff reductions -not only for workers in the directly affected manufacturing industries, but also other (mostly less-educated) workers in the same localities. Hakobyan and McLaren (2016: 729) concluded that “the distributional effects of NAFTA are large for a highly affected minority of workers.” Studies of adjustment costs suggest that some of the productivity gains from trade liberalization come, at least in the short-to-medium run, at the cost of job losses in less efficient firms or plants that cannot compete without tariff protection. For example, Trefler (2004) found that the fall in Canadian manufacturing employment as a result of Canadian tariff reductions in the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) of 1989, which preceded NAFTA, was of a similar order of magnitude to the productivity gains. On the Mexican side, Borraz and López-Córdova (2007) showed that the gains from globalization were very uneven regionally, with workers in the northern and border regions gaining more than in most other parts of Mexico.

Contrary to prior expectations, trade liberalization seems to have contributed to greater wage inequality (a higher wage premium for more educated workers) in Mexico as well as the United States (Feenstra and Hanson, 1997; Revenga and Montenegro, 1998; Hanson, 2004). This outcome is generally explained by a shift to more skill-intensive production in Mexican export industries (Esquivel and Rodríguez-López, 2003; Verhoogen, 2008). Overall, trade liberalization brought consumer gains to Mexican households, but these gains were concentrated in upper-income households and the northern and border regions (Nicita, 2009). Although official data show inequality at the household level falling in Mexico after the mid-1990s, estimates that correct for missing data for the top income decile show inequality rising rather than falling between 1994 and 2012 (Esquivel, 2015). In both Mexico and the United States, the labor share of national income has been falling since the late 1990s or early 2000s (Ibarra and Ros, 2019). Elsby et al. (2013: 1) attribute part of the decline in the U.S. labor share to “offshoring of the labor-intensive component of the U.S. supply chain.” Trade agreements like NAFTA are often argued to have contributed to these trends because they protected corporate property rights (but not labor rights), facilitated offshoring of manufacturing jobs, and put U.S. workers into competition with lower-paid foreign counterparts (Bivens, 2017).

Recent Growth of Mexico’s Manufacturing Industries and Employment

More context for the changes that the Trump administration sought in USMCA can be seen in the rapid growth of Mexico’s manufacturing sector in the most recent period leading up to the NAFTA renegotiation. Figure 1 traces the growth of Mexico’s total manufacturing output since the formation of NAFTA in 1994, compared with a parallel measure for the United States. To facilitate the comparison, the (seasonally adjusted) indexes of industrial production in the manufacturing sector for both countries were re-based to equal 100 in 1994.

Sources: Author’s calculations using data for Mexico from INEGI (n.d.), and for the United States from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2021). Data for both countries were re-based to 1994 = 100 by the author.

Figure 1 INDEXES OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION, MANUFACTURING SECTORS, MEXICO AND UNITED STATES (monthly, January 1994 to May 2021) (1994 average = 100, seasonally adjusted)

Initially, Mexico’s manufacturing production lagged behind that of the United States as a result of the 1994-1995 peso crisis, but then it recuperated and grew strongly up to 2000, aided by the NAFTA tariff reductions, strong U.S. growth, and the competitive impact of the depreciated peso. After a recession in 2001, Mexican manufacturing output then went through a prolonged period of stagnation until 2007. As a result of renewed peso overvaluation and the penetration of China into North American markets (Gallagher, Moreno-Brid, and Porzecanski, 2008; Feenstra and Kee, 2009; Hanson and Robertson, 2009; Dussel Peters and Gallagher, 2013), Mexican manufacturing output recovered slowly in the early 2000s and as of 2007 only barely exceeded its previous peak of 2000.

Both countries’ manufacturing output declined sharply during the financial crisis and “Great Recession” of 2008-2009 and recovered thereafter. But the two series diverged after 2014, when U.S. manufacturing production flattened out and never reached its previous peak of early 2008, while Mexican production grew rapidly right up until the COVID pandemic crisis of 2020. In the 2014-2019 period, Mexico benefited from a more competitive real exchange rate and the long-term payoff to strong investments in key sectors, especially automobiles. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, the peso depreciated significantly in real terms around 2015, and during the entire period from 2015 to early 2021 it remained about 20 percent lower compared to its 2007 real value. This coincides almost exactly with the improved performance of Mexican manufacturing output shown in Figure 1.

Note: A higher value indicates a real appreciation.

Source: Darvas (2012).

Figure 2 REAL VALUE OF THE MEXICAN PESO (monthly, January 2007 to May 2021) (Index, December 2007 = 100)

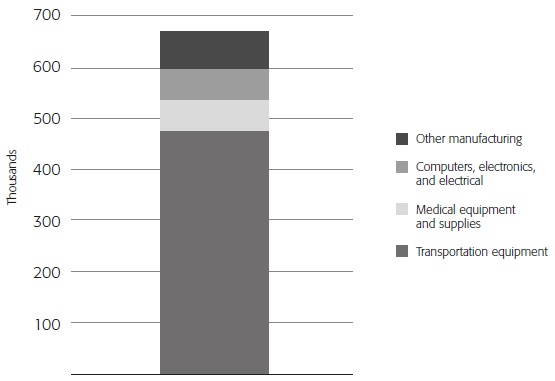

As a result of this strong increase in manufacturing production, Mexico finally achieved as ignificant and sustained increase in formal-sector employment in manufactures, which had eluded it in the first two decades of NAFTA (Blecker, 2014; 2016). As shown in Figure 3, employment in large firms in the Mexican manufacturing sector rose by 670,000 between 2007 (the previous cyclical peak) and 2019 (the most recent peak, and the last year before the COVID crisis), representing a 20 percent increase over the 2007 level of about 3.3 million.9

Note: Transportation equipment is Sector 336; medical equipment and supplies is 3391; computers, electronics, and electrical equipment is the sum of 334 and 335; and other manufacturing is all other industries in manufacturing (31-33), using the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS).

Source: Author’s calculations using data from INEGI (2007-2019). Averages of monthly data (not seasonally adjusted) were used for each year; increases for 2007-2013 and 2013-2019 were calculated separately from the two different surveys and then added together.

Figure 3 INCREASES IN EMPLOYMENT IN MEXICAN MANUFACTURING (2007-2019) (thousands)

In contrast, total U.S. manufacturing employment fell by 1.1 million during the same period (BLS, 2021). The coincidence of these trends does not, of course, prove causality, and most analyses concur that imports from China were quantitatively more important than imports from Mexico in any displacement of U.S. jobs (see Autor et al., 2016).

The increase in Mexican manufacturing employment in 2007-2019 was not even across manufacturing sectors, but rather concentrated in just a few. The transportation equipment sector (which consists primarily of automobiles and auto parts in Mexico) accounted for 475,000 of the new jobs, or 71 percent of the increase. Other sectors that registered large increases included computers, electronics, electrical equipment, and medical supplies and equipment, which together accounted for almost 120,000, while the remaining job increases were scattered around other industries. The fact that U.S. employment in motor vehicles remained flat (at about 994,000) between 2007 and 2019 (BLS, 2021) while Mexican employment in that sector rose by nearly a half million helps to explain the strong focus that the Trump administration placed on rewriting the rules for automobiles in USMCA, as discussed in the next section.

New Provisions of the USMCA and Their Likely Impact

As noted earlier, the Trump administration’s effort to disrupt North American economic integration and promote reinvestment in the U.S. economy led it to seek three main types of provisions in USMCA, which are covered here in turn.

Stronger Content Rules for Automobiles

The USMCA contains three new or revised requirements for automobiles to qualify for tariff-free trade within North America (USITC, 2019: 74-81). First, the rule of origin for autos was raised to require 75 percent North American content, up from the previous 62.5 percent. Second, 70 percent of the steel and aluminum used in automobiles must be sourced from North American producers. Third, 40 percent of the value of a passenger car (45 percent for a pickup truck or cargo vehicle) must be produced by labor earning a minimum of US$16 per hour. This last provision, now known as a “labor value content” (LVC) requirement, was a compromise reached after Canada and Mexico rejected Lighthizer’s original proposal of an explicit U.S. content requirement for vehicles to be sold tariff-free in the United States. Of course, the intention was the same: to induce automotive producers to relocate parts of their production operations to the United States (or Canada), where autoworker wages easily exceed that threshold. In addition, the USMCA requires more stringent verification of the ultimate national origins of all automotive inputs to ensure that “non-originating” (non-North American) inputs are not included in the regional content calculations-a provision largely aimed at imports from Mexico that might include parts or components sourced from China.

Although Trump’s team hoped that these provisions would induce a return of significant automotive and related upstream production (especially steel) to the United States, the actual impact may be very different from what they expected. The vast majority of cars produced in Mexico already meet the 75 percent regional content threshold (Fickling and Trivedi, 2018) and auto companies have several years to reach this target. The need to document the ultimate origins of all imported inputs adds complications and costs, but firms have the option of producing some inputs formerly imported from outside North America in Mexico rather than the United States in order to satisfy the regional rule of origin (Asayama and Yumae, 2020). In regard to LVC, some auto producers have decided to raise wages in Mexico to meet the US$16 per hour target rather than abandon investments already made there. For example, Nakayama and Asayama (2020) reported that Japanese companies, including affiliates of Honda and Toyota, were planning to increase wages at various Mexican plants. Alternatively, firms producing in Mexico could decide to fore go the USMCA tariff exemption and pay the U.S. most-favored-nation automobile tariff of 2.5 percent if the costs of compliance with USMCA requirements exceed the cost of paying the tariff. In addition, the LVC and other content requirements could induce greater automation of labor-intensive activities in the automotive sector, rather than a shift of such activities to the United States or Canada. For all these reasons, it seems unlikely that USMCA will instigate a massive relocation of automotive employment from Mexico to the United States.

What seems much more likely is that costs will rise for labor, steel, and other automotive inputs, which in turn will force auto producers to either raise prices for consumers or accept lower profit margins (or some combination of the two). In addition to the direct costs of meeting the new USMCA requirements, auto firms will face significantly higher administrative costs for verifying their compliance with the new rules -hence, the frequent complains of industry sources about “more paperwork” (Garsten, 2020). To the extent that the cost increases are passed on to consumers in higher prices, demand for vehicles produced in North America is likely to fall to some extent (and some demand could shift to imports from Asia or Europe).

A few studies have tried to quantify the likely net impact of the higher costs and new content requirements on automotive production in the three USMCA countries.

Burfisher, Lambert, and Matheson (2019) forecast that USMCA would cause decreases in Mexican output of 5.6 percent for motor vehicles and 2.1 percent for vehicle parts, and somewhat smaller drops for Canadian output (1.3 and 0.9 percent, respectively), while failing to increase U.S. output (which they predicted would fall by 0.03 percent for vehicles and 0.44 for parts).10 In contrast, Ciuriak, Dadkhah, and Xiao (2019) forecast that USMCA would increase U.S. shipments of automotive products by 1.9 percent, while reducing Canadian and Mexican shipments by about 0.6 percent each.

A more detailed picture emerges from the industry-specific model of “new light vehicles”( three categories of passenger cars plus pickup trucks) in USITC (2019), which estimates the effects of USMCA in the U.S. auto market at the “vehicle-model level” and then aggregates up the results. USITC (2019: 85) predicts average price increases ranging “from 0.37 percent for pickup trucks to 1.61 percent for small cars,” resulting in a total decline in U.S. consumption of all light vehicles of 1.25 percent. Also, USITC (2019: 86) predicts decreases in U.S. production ranging from 0.07 percent for pickup trucks to 2.96 percent for small cars. Nevertheless, USITC (2019: 87) forecasts a rise of 5.5 percent in total industry employment (or about 28,000 jobs), once the reshoring of a certain portion of auto parts is taken into account. This, of course, is a very small increase in the context of the U.S. economy or manufacturing sector as a whole.

All three studies (Burfisher Lambert, and Matheson, 2019; Ciuriak, 2019; USITC, 2019) predict that U.S. automotive imports from Canada and Mexico will decrease, while U.S. imports from other countries will increase but by less than imports from Canada and Mexico will decrease. Of course, the exact quantitative estimates in these studies should be taken with caution, but they generally concur in the qualitative finding that any U.S. gains in automotive production or employment as a result of USMCA are likely to be very small at best or possibly negative (small losses), and to come at the expense of losses (or larger losses) for Canada and Mexico.

As of MID-2021, there were still mixed signals for how USMCA will affect automobile production and trade. On the one hand, Mexican exports of auto parts reached a historical record level in the first four months of 2021 (Sánchez, 2021). On the other hand, Mexican and U.S. officials were still wrangling over how to interpret the USMCA requirements for automobiles, with the U.S. reportedly insisting on stricter interpretations (for example, of the LVC provisions) than what Canada and Mexico believed they had agreed to (Morales, 2021). Since the full USMCA requirements for autos do not go into effect until 2023 and their interpretation is still being negotiated, the longer-term outlook for autos remains unsettled.

Increasing Uncertainty for Foreign Investors

Crowley and Ciuriak (2018) used the phrase “weaponizing uncertainty” to characterize the Trump administration’s trade policy in general, including the numerous tariffs that were either imposed or threatened and the undermining of the World Trade Organization (WTO), as well as the renegotiation of NAFTA. The phrase surely describes several key new provisions that Lighthizer pushed to include in USMCA, especially the weakening or elimination of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), the new sunset clause, and the U.S. refusal to exempt Canada and Mexico from future national security tariffs, all of which were aimed at diminishing the security of future foreign investment in Mexico.

ISDS was one of the most controversial features of the original NAFTA agreement. Former NAFTA Chapter 11 gave broad protections for foreign investors’ property rights, by not only prohibiting actual expropriation of foreign firms’ assets, but also allowing corporations to file complaints to NAFTA tribunals for any government policies that were alleged to be “tantamount to expropriation.” Taking advantage of this broad definition, numerous firms filed ISDS claims against governments (national, state/provincial, or local) in each of the three countries about various types of regulations (for example, environmental laws) that could reduce potential corporate profits even for investments not actually undertaken. This process allowed foreign companies to claim compensation for property rights that were not recognized for domestic business firms in the laws of any of the member countries. Critics long argued that ISDS had a chilling effect on governments that wished to adopt socially beneficial health or environmental regulations because of the constant threat of costly ISDS lawsuits, even if such suits were not always successful -and sometimes they were; see Public Citizen (2021).

The USTR made weakening ISDS a priority in the NAFTA renegotiation, not because the Trump administration liked social or environmental regulations, but because Lighthizer viewed ISDS as creating “political risk insurance for outsourcing” that implicitly subsidizes foreign companies that invest in Mexico (Miller, 2018). Under USMCA, the existing ISDS process is abolished entirely for the United States and Canada, since the latter chose to “opt out.” For the United States and Mexico, USMCA severely weakens ISDS, leaving it as an option that can be pursued only if litigants first attempt to use national courts, and only for actual expropriation (the “tantamount to” loophole was eliminated). USMCA grants an exception to maintain full ISDS protection for foreign firms that have invested in the Mexican energy and infrastructure sectors, but this is a relatively limited exception.

One non-governmental organization (NGO) that had long criticized ISDS described the changes in USMCA as follows:

The main U.S.-Mexico investment annex excludes the extreme investor rights relied on for almost all ISDS payouts: minimum standard of treatment, indirect expropriation, performance requirements and transfers. The pre-establishment “right to invest” is also removed. A new process requires investors to use domestic courts or administrative bodies and exhaust domestic remedies or try to for thirty months. Only then may a review be filed and only for direct expropriation, defined as when “an investment is nationalized or otherwise directly expropriated through formal transfer of title or outright seizure.” .

The new process bans lawyers from rotating in the system between “judging” cases and suing governments for corporations, and forbids “inherently speculative” damages to counter the outrage of corporations being awarded vast sums based on claims of lost future expected profits. (Public Citizen, 2018)

These changes should eliminate the most egregious abuses of ISDS, but are unlikely to inhibit normal foreign investment in Mexico. Mexico has already adopted intellectual property laws and guarantees for foreign investors that meet NAFTA (and USMCA) standards, and Mexico has kept those standards in place precisely to reassure foreign investors. Mexico also renewed similar commitments when it joined the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which was formed after Trump withdrew the U.S. from the earlier TPP agreement (and the 11 countries that stayed in decided to “suspend” some of the U.S.-backed provisions, including some related to extended patents and ISDS). Indeed, the weakening of ISDS for Mexico could have a beneficial side effect (unintended by Lighthizer): it could enable the Mexican government to take advantage of greater “policy space” to enact social and industrial policies that would better promote the country’s long-term development and foster green growth. In any case, Mexico’s ability to attract foreign investment will depend much more on the country’s own government and institutions than on the ISDS procedures.

Another way that Lighthizer tried to increase uncertainty in North American trade was by including a sunset clause in USMCA. The new agreement has a term of sixteen years, with a review to be conducted after six years leading to a new renegotiation and potential renewal. This represented a compromise over Lighhizer’s original demand that the agreement would face abolition every five years unless it were renegotiated again and again; it was accepted by Canada in exchange for the USTR giving up on the elimination of state-to-state trade dispute settlement panels (former NAFTA Chapter 19). The sixteen-year term and six-year review process will surely allow business firms to do more long-term planning for their North American operations compared with the five-year sunset approach originally proposed by the USTR.

Instituting a process for periodically reviewing and revising USMCA is potentially a positive change; one of the weaknesses of NAFTA was that it contained no procedures for amendment or updating. Of course, a procedure for review and revision does not have to include the threat of termination after a fixed period like sixteen years. The sixteen-year sunset provision is one that Mexico and Canada accepted only reluctantly. Nevertheless, the Mexican and Canadian governments will likely welcome an opportunity to renegotiate USMCA starting in 2026, especially if the U.S. administration in office at that time is less protectionist and belligerent than the Trump team.

Yet one more effort to increase uncertainty was the U.S. refusal to exempt Canada and Mexico from future applications of Section 232 “national security” tariffs, such as the ones Trump had imposed on imports of steel and aluminum. Trump’s advisors discovered that this formerly obscure provision in U.S. trade law, which was rarely used by his predecessors, granted him virtually unlimited discretion to protect any U.S. industry by claiming that domestic production is essential for the national interest. Canada and Mexico did obtain a waiver of Trump’s 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum several months after USMCA was negotiated, in exchange for which they rescinded their retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports. They also obtained “side letters” that would have exempted their auto exports (up to certain limits) if

Trump had implemented his threatened Section 232 tariff on automobiles (Stuart, 2018), but that threat has become moot since current U.S. President Joe Biden has not renewed it. Still, Canada and Mexico could be subject to other U.S. national security tariffs in the future, and USMCA grants them no exemption.

Labor Rights

USMCA includes major improvements in the treatment of labor rights, not only in comparison to the original NAFTA (where labor issues were relegated to a separate and unenforceable side agreement), but also compared to later U.S. trade agreements (which, after 2000, generally did include some labor rights provisions in the main text). USMCA requires the members to adhere to International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards; not to “derogate” (weaken) their labor rights regulations in ways that would affect trade; to respect workers’ collective bargaining rights, including by allowing workers “to organize, form, or join the union of their choice”; not to import goods produced using forced labor; to address violence against workers; to afford protections to migrant workers; and to maintain protections against workplace discrimination (USITC, 2019: 215-217). An appendix to the labor chapter specifically requires Mexico to establish “an independent entity for conciliation and union collective bargaining agreement registration” and “independent Labor Courts for the adjudication of labor disputes” (Inside U.S. Trade, 2019). After the negotiations concluded, Mexico modified its labor laws to conform to these and other new requirements in USMCA.

After the original USMCA negotiations in 2018, U.S. labor unions and congressional Democrats complained about weak enforceability of these provisions, especially collective bargaining rights. In response, Lighthizer went back to the negotiating table and won stronger enforcement mechanisms, which helped to persuade many unions and Democrats to support approval of the final (modified) agreement. In particular, the parties agreed to create a rapid response mechanism (RRM) that would prevent the adjudication of complaints from dragging on for many years through the regular trade dispute settlement mechanism. Labor advocates especially hope that the new USMCA requirements, combined with enforcement through the RRM, will impede the formation of “protection unions” or yellow unions (company-sponsored unions that are not chosen by workers and do not represent them) in Mexican exporting firms.

In 2021, two complaints were filed about alleged violations of workers’ rights in Mexico: one at an auto parts plant at Tridonex (a subsidiary of a U.S. corporation) in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and another about an allegedly fraudulent election at a General Motors plant in Silao, Guanajuato (Lynch, 2021; Saldaña, 2021). In response,

Tridonex agreed to pay more than US$ 600,000 in back pay to laid-off workers (El Financiero, 2021). Also, the U.S. and Mexican governments agreed that a clean and internationally monitored election would be conducted at the GM plant in Silao; the workers ultimately voted to reject the contract previously negotiated by a union affiliated with the Confederación de Trabajadores de México (CTM) (Rodríguez, 2021). Also, the Mexican government filed a complaint about U.S. violations of the rights of migrant workers, which the Biden administration promised to investigate (Saldaña, 2021).

These efforts provide some hope that USMCA will prove to be a valuable tool for protecting workers’ rights on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border, especially as long as both countries have leaderships committed to enforcing the new rules in a cooperative manner. If Mexican workers can form independent unions and negotiate for better wages and working conditions, this could help alleviate inequality in Mexico. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how much the push for enhanced labor rights will affect investment, production, employment, and wages in Mexico’s export industries, or if it will have any appreciable impact on the U.S. labor market. Even if all labor rights were fully and effectively enforced in Mexico, Mexican wages would remain significantly lower than U.S. wages for the foreseeable future. In the end, the labor rights provisions of USMCA may possibly do more to help Mexican workers than American ones.

Conclusions and Prospects

It is still too early to reach firm conclusions about the long-term impact of USMCA, and even the short-run effects can be difficult to discern since the agreement went into effect in the midst of a global pandemic and economic crisis in 2020. So far, however, the Trump administration’s efforts to increase uncertainty have done little to inhibit foreign investment in Mexico. Before the pandemic struck, in the first quarter of 2020, when USMCA had just been passed by the U.S. Congress and while Trump was still in office, inflows of foreign direct investment into Mexico reached their highest quarterly level in the previous decade at US$21.7 billion (IMF, 2021a). By MID-2021, Mexican government officials were touting USMCA as increasing confidence in the Mexican economy and crediting it with helping to boost the recovery from the COVID crisis. Mexico’s Secretary of the Economy Tatiana Clouthier has been quoted as saying, “Thanks to the agreement, dynamic trade has been maintained with clear rules, which generate certainty in the commerce and investments made in North America” (Usla, 2021, emphasis added). Thus, the successful conclusion of USMCA negotiations may have done more to enhance confidence in Mexico than any of the supposedly uncertainty-increasing features of the agreement will do to reduce it.

Overall, it appears very unlikely that the USMCA will accomplish the goals that the Trump administration intended to achieve when it launched the NAFTA renegotiation. As of MID-2021, there is no sign that the content rules for automobiles, weakening of ISDS, the sunset clause, and other new features of USMCA are leading to a massive exodus of firms from Mexico or significant reshoring of jobs to the United States. At most, the new rules for automobiles could increase U.S. employment by small amounts, but even that is uncertain, and any such small gains would come at the expense of losses to Mexican and Canadian producers and consumers in all three countries. Even without the extreme form of ISDS included in the original NAFTA, USMCA still commits Mexico and the other parties not to engage in direct expropriation, and hence protects the basic property rights of foreign investors. If U.S. trade tensions with China persist-as they have, in the first nine months of Joe Biden’s presidency-Mexico stands to gain from being seen as a less risky destination for foreign investment compared with China.

The specific new features in USMCA can only be described as a “mixed bag.” Positive aspects include the reform of the ISDS regime for Mexico (and its elimination for Canada) and the strengthening of protections for labor rights. The sunset clause, although intended to foster greater uncertainty for investors, will provide a welcome opportunity to revisit the agreement and modify it starting in 2026. The biggest negative is probably the automotive provisions, which are likely to make North American automobile production more expensive and less competitive, thereby potentially increasing imports from outside the region. Initially, however, firms that engage in automobile production in North America appear to be designing strategies to cope with the new regulations and are not announcing major changes in their investment plans. If the USMCA was supposed to “make America great again” by inducing a large-scale repatriation of manufacturing production to the United States, it appears doomed to fail.

In the end, perhaps the most important thing about USMCA is simply that an agreement was reached and went into effect, thereby preventing the far worse disruption that would have resulted from a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA. However, the formation of USMCA also represents a huge missed opportunity. In spite of the modifications discussed here, USMCA largely continues the NAFTA policy model, which as discussed earlier did not lead to convergence of Mexico with its richer neighbors to the north. As Ciuriak and Fay (2021) have written, “The NAFTA framework resulted in Mexico capturing the low-economic-rent industrial activities, while the United States, which did have a KBE [knowledge-based economy] policy, captured the higheconomic-rent knowledge-based activities such as R&D and design/branding of products” (Ciuriak and Fay, 2021: 13). Nothing in USMCA would alter this trajectory, and some of the new provisions for e-commerce (prohibitions on data localization) could worsen it by further concentrating information technology and data collection in U.S.-based Internet giants like Amazon and Google. In addition -with the notable exception of the labor rights provisions-, the USMCA contains no commitment of the three member countries to cooperate in adopting policies to make the whole region more competitive, prosperous, and equitable. The omission of any provisions related to climate change is also a notable weakness. Progress on all of these fronts will require new initiatives that go beyond the narrow framework of USMCA.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)