Introduction

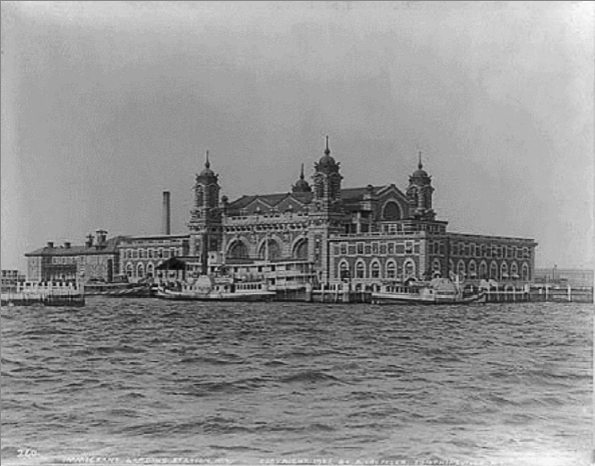

Ellis Island is a small island south of Manhattan, New York. The approximately 12 000-m2 island boasts several U.S. government buildings, outstanding among them, a major hospital complex and a set of structures that used to house the Ellis Island Immigration Station. During the period it operated as the immigrant processing station (1892-1954), the station processed an estimated 20 million people who applied to enter the United States. Even though during the twentieth century, management of the island’s monumental group of buildings faced several difficulties, in 1990, the building originally used for immigrant reception and housing was converted into the Ellis Island Immigration Museum. Like the other century-old buildings on the island (Figure 1), the center is managed under the auspices of the Statue of Liberty National Monument heritage complex (Pardue, 2004), one of the most visited in the United States.

Recently, supposedly due to the exceptional immigrant flow, Ellis Island has been publicized by the U.S. government as a “remarkable illustration of the great Atlantic migration” from the end of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, more specifically a kind of “unparalleled icon of international migration history” (UNESCO, 2017). Based on this historicity, in April 2017, the U.S. Department of the Interior submitted a proposal to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to make Ellis Island a world heritage site. The argument is that the island’s architectural complex witnessed an exceptional period of world history, especially the movement of millions of people who left Europe to live in North America.

Within the framework of the research project “Behind the Backstage of UNESCO: The Making of Consensus on World Heritages Sites (1960-1980),” developed with funding from the University of Joinville Region’s Research Support, this article proposes to socialize the results of a study regarding the application for Ellis Island to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The article is organized in three parts. First, I will present information about Ellis Island’s history, pointing out some of its different uses during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To that effect, I begin a theoretical-methodologic dialogue with the relevant historiography, seeking to discuss some important markers related to the island’s past. Next, I will describe and analyze some documents relevant to the application to make Ellis Island a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Therefore, I describe the U.S. government arguments justifying the application’s pertinence, as well as the need for the unesco to acknowledge the exceptional universal value of Ellis Island in the history of the international migrations (Gfeller and Eisenberg, 2016).

In the last section of the article, I will discuss what the U.S. gov ernment’s undertaking of making Ellis Island a world heritage site means, at this moment when we watch that government’s powerful initiatives to regulate and/or discourage the displacement of migrants toward the United States (Heinich, 2018: 175).

Ellis Island: Brief Notes about Its Historicity

It is a commonly discussed fact in historiography that Ellis Island was a subject of multiple uses in the past. However, though the region had already been registered in older documents, it was only during the seventeenth century that it began to be explored by residents, as well as by merchants passing through Manhattan. Besides being used as a stopping-point for people navigating around Manhattan, in the seventeenth century, Ellis Island was an outstanding support point for military and commercial vessels going to New York City (Kalin, 1989).

At that time, still popularly known as the “Oyster Islands,” alluding to the diversity and quantity of shells on its beaches, Ellis Island received some improvements, many financed by Michael Paauw, a Dutch merchant who became the area’s owner after having relative success in the colonial undertaking “New Amsterdam,” led by the Dutch West India Company (Stakely, 2003).

During the 1770s, the military uses of Ellis Island were intensified. After being sold to Samuel Ellis, a rich beverage merchandiser in the area, it was commonly used as a place of atonement, mostly a surveillance-free area that could be used to hang pirates and other undesirables who occasionally plundered Manhattan (Unrau, 1984).

Even though historians have not detailed the reasons, in the 1790s, Samuel Ellis chose to lease Ellis Island to the New York government. After the demolition of the main buildings, a marine fortification was built that even had a prison complex intended for detaining and punishing New York criminals. In 1808, almost ten years after Samuel Ellis’s death, his heirs decided to sell the island to the State of New York for the amount of about US$10 000 (Unrau, 1984).

However, it was only in the nineteenth century that Ellis Island consolidated itself as permanent locale for the military protection of New York. In 1808, in the same year that the State of New York won the judicial dispute related to the purchase and ownership of the island, it resold it to the U.S. government. Four years later (1812), in that same place, what was called “Fort Gibson” was already in operation (Figure 2), a kind of army headquarters where a “gunpowder storehouse and a battery of artillery positioned along the east coast of the Island” were located (NPS, 2015).

Besides its conspicuous defensive function, Fort Gibson was also historically used as a “prison camp,” especially between 1812 and 1814, during the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain (NYSMM, 2006).

Even though Fort Gibson had been decommissioned in the 1860s, the military uses of Ellis Island continued and lasted nearly 80 years. However, in the 1890s, the establishment of an immigrant processing station gave the island a new social use.

According to Maddern’s explanation (2004), before 1892, the first year the Ellis Island Immigration Station operated, immigrants moving to New York were processed by employees of the American Immigration Department, inside Fort Clinton/Castle Garden in Lower Manhattan. Between 1855 and 1890, approximately eight million immigrants were processed there.

Built with federal funds between 1890 and 1892, the Ellis Island Immigration Station responded to recent changes in U.S. Immigration Law: in 1891, the management of the swiftly increasing migration was definitively transferred to the federal government. Among others, the Immigration Act of March 3, 1891 gave institutional status to the United States Immigration Department and stipulated the structure needed for the inspection and processing of international immigrants who applied for a “official permit” to live in the country (Library of Congress, 1891: 1084).

In order to ensure enforcement of the law, the U.S. government made many efforts to adapt the island to its interests, two of which may have had the most impact on its landscape. First, it doubled the size of Ellis Island by means of several landfills. And, then, in addition to ordering the demolition of some buildings, it restored others previously used for military purposes. The government’s aim was to ensure the opening of the Ellis Island Immigration Station in January 1892, that is, less than a year after the Immigration Act of 1891 came into force (Figure 3).

At its commissioning, the Ellis Island Station became a strategic base to “police European immigration to [U.S.] America,” especially of migrants who tried entering the country through New York’s East Coast. According to Maddern (2008), between 1892 and 1924, the Ellis Island Immigration Station was a space where different kinds of “eugenic ideas” circulated, many related to “genetic difference” tests, comparing populations of different regions of the planet. Furthermore, the island would also be a lower profile space to test “new medical techniques on the migrants passing through” (Maddern, 2008: 361).

In June 1897, the station’s entirely wood structure was destroyed by a huge fire. In that same year, the United States government promoted a contest for architectural firms to present their projects for the design of a fireproof immigration station. The contest winner was a project developed by New York architects William Alciphron Boring (1859-1937) and Edward Lippincott Tilton (1861-1933), partners and owners of Boring & Tilton Architecture. Based on the winning design, the first building constructed was the main building of the Immigration Station (Figure 4), opened December 17, 1900. After its conclusion, the kitchen/laundry building and the electric power station were finished in 1901. In March 1902, the main hospital building was opened (NPS, 2014).

In the following years, other buildings were erected. Between 1902 and 1909, the island’s perimeter was raised using new landfills, creating space for the construction of a hospital complex, which included an administration building, a set of isolation units for people with infectious and contagious diseases, and a sector to treat individuals with different degrees of psychopathy.

Even though the early twentieth century provided Ellis Island with a most robust infrastructure, in the 1910s and 1920s, the migrant flows processed there decreased considerably. Changes in national legislation (the so-called Quotas Act) stipulated that each group of immigrants arriving in the United States should be separated and counted by nationality. Once this procedure was carried out, the number of immigrants of a certain nationality could not exceed 3 percent of the U.S. population, according to the 1910 census.

The coup de grace was the Immigration Act of 1924, which reduced that number even more: a maximum of 2 percent of immigrants from the same nationality could be admitted, using the results of the 1890 census. That same law required that all immigrants be inspected in their home country. In that way, they attempted to keep the immigrants in their own countries, avoiding unnecessary difficulties for the U.S. government, like eventual deportation costs, intermediate conflicts arising from Ellis Island overcrowding, and/or the proliferation of diseases in New York (Library of Congress, 1924).

It is interesting to observe that a combination of increasingly restrictive national immigration legislation and the deep economic crisis that devasted the United States between 1929 and 1931 contributed to the decline of the Ellis Island Immigrant Station. In the face of these difficulties, in 1930 and 1940, the island and its buildings began to be used as an operational base for the Coast Guard and place to detain foreign prisoners during World War II (Maddern, 2004).

In 1954, with most of its buildings already in ruins, the station’s activities ended. Thus, it was not until the 1960s that the Ellis Island Immigration Station was (re)produced with new social value, turning into part of the United States cultural heritage and integrated into the Statue of Liberty monumental complex. The next section deals with this discussion.

Ellis Island: From U.S. Heritage to UNESCO World Heritage

In patrimonial terms, an important milestone in Ellis Island’s history was its integration into the Statue of Liberty National Monument in November 1965. At that time, on initiative of President Johnson (1963-1969), management of the island and its ruins passed to the U.S. Park Service. Although in charge of places of other historical interest, especially places related to U.S. military history (namely, forts and battle fields), this body has not had the expertise to produce and disseminate Ellis Island’s heritage.

According to Maddern and Hoskins (2010: 305), when the Park Service took over Ellis Island management, “It did not know practically anything about immigration,” especially about “Ellis Island’s history.” During the 1960s, the Park Service was “forced to gather specialists in history, historians who knew how immigration,” has become an extremely complex social phenomenon decade after decade and has connected cultural differences that crisscrossed past European and U.S. societies (Maddern and Hoskins, 2010: 305).

Furthermore, between 1954 and 1965, the Ellis Island buildings deteriorated very quickly. In addition to not being able to rely on specialized restoration, the Parks Service also stated that the old Immigration Station “did not serve any useful purpose.” So, it was not worthwhile to burden the government’s coffers with the high cost of restoring the island complex. The truth is that, “for more than 20 years,” a long “dispute involving federal, state and local governments, commercial investors, and experts in preservation” about what should be done with Ellis Island ensued (Maddern and Hoskins, 2010: 306).

To save the island, a public-private partnership has been planned, with the private sector and federal government side by side. The idea was to create an Ellis Island Immigration Museum with private investment, given that the main challenge to creating the museum was the lack of funds for restorations.

Although a lot had been planned, indeed, the establishment of the museum was only ensured in 1982 when President Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) named Lee Lacocca, a rich New York businessman and son of Italian immigrants, manager of the Statue of Liberty - Ellis Island Foundation.1 Using Lacocca’s prestige, but also gathering state, corporate, and volunteer organizations together, many fundraising campaigns have been held for Ellis Island restoration. In order to get a better idea of these campaigns’ success, in 1990, the year of the Ellis Island Immigrant Museum opening, the huge amount of US$150 million was raised for island restoration (Maddern and Hoskins, 2010: 306).

The U.S. government took an important step in April 2017 regarding the acknowledgement of Ellis Island as a world heritage site. In that year, the Department of Interior submitted for UNESCO perusal the application based on the following:

Ellis Island is a remarkable illustration of the Great Atlantic Migration, the voluntary mass migration in which millions of people, mostly from Europe, moved to North America and South America from the mid-nineteenth through the early twentieth century. Most of these people -about 17 million between 1880 and 1910 (37 million between 1820 and 1980)- went to the United States, and approximately 70 percent of the immigrants entering the United States during the first half of the twentieth century were processed at Ellis Island, as well as the 2 percent of arrivals who were turned away. The evidence of this activity is preserved in the complex of building remaining on the island, with more than 40 extant buildings . . . that represent all aspects of the immigrant arrival process and experience, as well as later periods when immigration to the United States was more restricted. The museum of immigration of Ellis Island, in the main building and kitchen laundry building, presents this history to visitors, who can see many of the restored facilities, historic objects and immigrants’ stories. (UNESCO, 2017)

Based on Criteria IV, of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972), the U.S. government justified the importance of the Ellis Island application as part of the world’s heritage due to its being an “outstanding example of a kind of building, of an architectural or technological ensemble or setting that illustrates a significative stage in human history” (UNESCO, 2017).

Furthermore, the government also stated that the station, converted into the Immigration Museum, still contained “the full range of the physical infrastructure that was required to receive, physically examine, treat, question, and release or detain the . . . immigrants” who arrived in the United States between 1892 and 1924 (UNESCO, 2017).

In the same way, the application also mentions that “its location on an island, where the only later function has been the presentation to the public of its history, has preserved the heritage complex, leaving it intact.” Thus, it would be the very “integrity” of the buildings of Ellis Island that would mirror its “authenticity” as a world heritage site. According to the application,

the form, design, materials and interrelationships of the buildings on their island setting are authentic reflections of the activity at Ellis Island during the years when it served as the main portal for immigration to the United States from Europe, and during later periods until the mid-twentieth century as well. (UNESCO, 2017)

Reinforcing that the application was supported by an “history . . . , well documented, bolstered by the research that supports the Ellis Island Museum of Immigration,” the project also pointed out the “outstanding” nature of Ellis Island when compared to cultural properties of a similar nature:

There are other global properties associated with the Great Atlantic Migration such as Pier 21 in Halifax Canada, Hospedaria de Imigrantes (Immigrants’ Hostel) in São Paulo, Brazil, and Hotel de los Inmigrantes (Immigrants’ Hotel) in Buenos Aires, Argentina; quarantine stations such as the Lazaretto in Philadelphia and Grosse Île in Canada; and emigration facilities such as the Tullhuset (Customs House) in Gothenburg, Sweden, the Red Star Line harbor sheds in Antwerp, Belgium, and Dworzec Morsk . . . in Gdynia, Poland. It is believed that, while these properties illustrate various aspects of the Great Atlantic Migration, Ellis Island is associated with a significantly large proportion of the historical phenomenon and has preserved, through its island setting and lack of later uses, a more complete representation of the immigrant reception and examination process. (UNESCO, 2017)

As can be observed, the historic narrative strategically developed by the team connected to the U.S. Department of the Interior, above all, signals a resourceful intellectual undertaking of “those in charge of producing the heritage”: it is a large group of professionals from different areas of knowledge acting to “select an artifact to be included in a heritage complex” of national and international interest (Heinich, 2018: 177).

There are no doubts that by trying to establish Ellis Island as a UNESCO world heritage site we should know why and to whom it would be of interest to produce a heritage corpus whose value is rhetorically based on the migrants crossing at the end of nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. To conclude, in the next section, I present some considerations in this regard.

Conclusion: Why and for Whom Would Ellis Island Matter as a World Heritage Site?

Nowadays, the former Ellis Island Immigration Station houses a three-floor museum of texts, photography, objects, official documents, and audiovisual narratives about the history of the lives of immigrants who in the past considered it a mandatory stop.

When the Ellis Island Immigration Station Museum opened in 1990, some politicians who had fought for its creation -especially President Johnson- feared that it would present its visitors with a misinterpretation of the historic events that had occurred there. The fear was that creating a more palatable past to the public would lead to the production of a museum space “similar to Disneyland,” where visitors could see and also interact with caricatures of migrants rehearsed by people “smiling” and “selling Coca-Cola” (Maddern and Hoskins, 2010: 307).

That has not happened, however; as a result of a public-private undertaking, the conversion of Ellis Island into part of the U.S. cultural heritage, by means of its association to the monumental Statue of Liberty complex, was a financial success in all aspects.

Recently, the U.S. government attempt to achieve acknowledgement of Ellis Island as a UNESCO world heritage site must be followed and analyzed with caution. In whose interests and why would establishing Ellis Island as a world heritage site be useful? It must be taken into account that this same government has been setting out regulatory policies and violent military strategies intended to contain migrant crossings toward it.

Based on this perspective, it must still be considered that the application does not seem to propose placing value on properties that contribute to the debate. Rather, it points to learning about a new kind global citizenship that sees heritage as an opportunity to think about the past and contributes to the perception of shared humanity in the present. This would jibe with what the UNESCO has laid out in programs like the International Coalition of Inclusive and Sustainable Cities, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Global Pact on Refugees, and the Global Pact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

If we agree with Andreas Huyssen (2014: 13) that in different Western societies, experiences over time are marked by presentism, we also need to recognize that the historicity of the “nation is no longer the singular continent of the collective memory.” Indeed, the “very expression ‘collective memory’ has become more and more problematic” in an increasingly globalized contemporary world. In this sense, the process of forging heritages brings a kind of “past-present culture” to life that, among other things, stimulates the good consciousness of certain governments that they are doing something effectively useful by maintaining their nation. Thus, it would not be surprising if we encountered new Ellis Island heritage initiatives. Apparently, the island’s application as a UNESCO world heritage site just seems to be another step in its unfinished process of making a cultural heritage.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)