INTRODUCTION

A review of the mainstream literature on skilled migration shows very few recent studies of skilled refugees in general and even fewer on Syrians in particular. This gap in the literature on conflict-induced displacement of skilled professionals (CIDSR) may be explained in various ways: first, it may be due to the difficulty of obtaining reliable quantitative and qualitative data; second, it could be due to their assumed small numbers in comparison to the overall quantity of temporary migrants; and third, it may be explained by their selection based on humanitarian considerations rather than on human capital attributes, as DeVoretz, Pivnenko, and Beiser (2004) assume.

Migrants in general and refugees in particular have often been viewed as uprooted people who could be a menace for the economy and social stability of destination countries. An earlier study by Malkki (1995: 26) deals with the “sedentarist metaphysics” that comes from our conception of the world as a “discrete spatial partitioning of territory” in the segmented fashion of the multicolored school atlas. The term “the nation” is commonly described using metaphoric synonyms like “the country,” “the land,” and “the soil” (Malkki, 1995: 26).

Compared to skilled economic migrants, Syrian refugees are people with roots in their country; they are connected to their territory and their migration is sudden and forced. They did not plan it, and that makes the process a lot more shocking than in the case of economic migrants. Furthermore, we do not know whether the migration of Syrian professionals is temporary or permanent. While previous studies show that only a fraction are likely to permanently resettle (Zong and Batalova, 2017), many of the skilled Syrians in the Diaspora do not themselves know if they will return or not.

When compared to the voluntary mobility of skilled workers through transnational companies or to the planned migration of what the previous literature has studied as the median skilled worker, skilled refugees are an extreme case both in numbers and context. As such, they are considered separately from economic migrants. However, previous academic experience has shown that extreme cases themselves can serve to broaden our view on the wider context of skilled professionals' migration.

This study explores the hypothesis that Syrian CIDSR is used by receiving OECD countries with two main purposes: a) to balance human capital needs to solve brain drain caused by internal conflict (Turkey) or to maintain growth in aging economies (Canada, Germany, and the UK); and, b) to strengthen their status as moral powers (Brazil, Mexico, and the U.S.).1 In short, Syrian skilled refugees pose a humanitarian crisis but also an economic and political opportunity for the main destination countries.

The purpose of this article is to offer a general view of the integration of skilled Syrian refugees into various countries and to identify different political approaches that could also serve as starting points for new field research. I combine the theoretical background of migration theory with case study techniques typical of international relations studies. Due to the lack of a regional policy for refugees in North America and Europe, a comparison among regions was not feasible. This study is narrowed, then, to a selection of seven OECD countries with significant international roles as refugee hosts: the main receiver of Syrian refugees in the world (Turkey), two European countries (Germany and the UK); two in North America (Canada and the U.S.), and two Latin American countries (Mexico and Brazil). The study was limited to these seven destinations taking into account the scarcity of information specifically regarding skilled refugees.

Previous literature on refugees has focused on the humanitarian aspects of their integration and very few studies have divided Syrian refugees into skilled and unskilled; this may be due to the novelty of the problem, the difficulty of identifying how many skilled individuals are living inside or outside the camps, and even ethical reasons. Since it is a humanitarian problem, it may seem unjust to give more relevance to one type of refugee in particular. However, I believe that comparing different populations among the Syrian refugees does not mean that we ignore the unskilled; on the contrary, we try to see if selectivity is applied when humanitarian purposes should prevail.

My main research questions are: How is conflict-induced displacement different from economically-driven skilled migration? Why do the countries selected accept Syrian refugees, and what are their integration policies compared to those for other migrants? Are traditional approaches on skilled migration useful for studying the vulnerability of skilled refugees?

The article is structured in four main parts: a) theoretical approaches to conflict-induced migration; b) general characteristics of Syrian refugees; c) cross-case analysis of the selected host countries; and, d) conclusions.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Skilled refugees are not a new subject of analysis, as there is previous literature on intellectual exile (Said, 1993, among others). However, the figure of the skilled refugee has powerfully re-emerged in the current context of global migration crisis. Skilled refugees, in particular Syrians, are not the typical cosmopolitan professional seeking to travel and not be bound to particular territories; skilled Syrians are not the scientific nomads of our times. Paraphrasing from a classic book on exile written in the nineteenth century by Victor Hugo (2014: 36), for the exiled, any land is the same as long as it is not the Syrian land. Exile is not a material problem, but rather a moral one.

Civelek (2017: 27-28) studies refugees as liminal subjects of international relations, citizens of their home countries but devoid of territory and without economic rights. Refugees in general are ambiguous individuals, finding themselves in an uncertain “transition” period, with no clear future. “The designation 'refugee' suffices alone to isolate her/him in the socio-political field. Moreover, as a member of a sub-population, the refugee poses a 'problem' to the upper-population” (Civelek, 2017: 28).

Due to the scant previous evidence on Syrian skilled refugees, we assume their situation is similar to the overall cohort of population in exile and that their roles are different from economically-driven migrants. As such, academically outstanding views on the economic migration of professionals are not suited to, or even clash with, the topic of CIDSR. I will, however, touch on studies that may help us compare conflict-induced and economically-induced skilled migration. For instance, the proposal of a Global Skills Partnership (Clemens, 2015), which involves an ex-ante public-private agreement to link skill formation and skilled migration for the mutual benefit of countries of origin, destination countries, and migrants, is not possible in a context of ethnic conflict and civil war. This type of brain drain is difficult to anticipate.

Recent literature on cosmopolitan identity might also clash with our object of study. For example, Skovgaard-Smith and Poulfelt (2018) show how foreign-based professionals define themselves as “non-nationals,” downplaying their own national affiliations and cultural differences. According to these authors, professional elites in the Diaspora demarcate their cosmopolitan “us” in relation to their original national (mono) culture. This type of cosmopolitan identity as a mode of collective belonging, part of a wider discourse of globalization, certainly coexists with the conflict-induced displacement of the skilled, but the two require very different methodological strategies.

Another approach to the skilled migrant´s identity is the quality distinction or discrimination between migrants' qualities: skilled vs. unskilled. Cranston (2017: 2) starts from a linguistic observation: while migrants are expected to stay abroad, it is presumed that “expatriates” will return to their home country. In the context of the rise in popularity of far right parties in Europe and the U.S., the former are considered bad and the latter, good. Restrictive migration policies would prioritize expatriates, but not migrants. The skilled “good” migrant is now expected to go abroad, work, and return to his/her home country. The questions that immediately emerge are: Do Syrian refugees plan to return? Are they able to? Are they good or bad, in terms of their contribution to the country of origin?

However, other aspects of the current discussion on skilled migration may be extremely useful for gaining insight about skilled refugees. Surprisingly, I may return to the discussion of knowledge colonialism and dependency theory (Maniglio, 2017: 28), which criticizes the way in which main destination countries define immigration quotas to reinforce their power over knowledge production and reproduction. In the case of refugees, being skilled is a double-edge sword, as they are eligible to an exclusive citizenship, being admitted into a country (such as Turkey), but they may not be allowed to leave, because of their skills.

The questions about skilled refugees and ethnic conflict have been addressed, to my knowledge, in four papers that precede this one: two based on statistical models (Bang and Mitra, 2013; Christensen, Onul, and Singh, 2018) and two qualitative economic analyses (Smith, 2016; Uzelac et al., 2018).

First, the pioneering study of Bang and Mitra (2013: 387) finds that ethnic civil war increases the fraction of tertiary skilled emigrants and also reduces the stock of professionals in the country of origin. Long-lasting ethnic civil wars may lead to the formation of skilled Diasporas that may eventually help with the resolution of conflict and the reconstruction of their economy of origin. Bang and Mitra's model proves the importance of the conflict's duration, in which each additional year of ethnic civil war increases the fraction of highly skilled emigrants by a minimum of 0.7 percent (2013: 399). In line with the mainstream economic literature on skilled migration, Bang and Mitra also confirm the positive effect of skilled migrants -in this case, refugees- for the host country.

Five years later, Christensen, Onul, and Singh (2018: 25) supplemented Bang and Mitra's study, showing that ethnic wars and conflicts also change the proportion of educated people in the economy. In this way, predictions may be made about human capital flight, therefore aiding in making effective policy recommendations.

A different qualitative study by Smith (2016: 29) calls for changing our perspective on refugees from burden to “boon,” appreciating their economic value, and adopting the “economy of sharing” typical of Islamic economies. Starting from fieldwork on the Syrian skilled refugees arriving in Germany, Smith elaborates on how the sharing economy redistributes surplus to a community. This economic model refers to the sharing of access instead of individual ownership and offers the potential for refugees to help one another and their local community, as well as to allow the local community to help them (Smith, 2016: 53-55).

A last study, by Uzelac, Meester, Goransson, and van den Berg (2018, 35), seems to be a continuation of Smith's proposal, since they describe two types of capital relevant for studying refugees: bonding capital, which is created among members of refugee groups, and bridging capital, which refers to the connections between individual refugees and outside actors, such as citizens of the host community or aid agencies. A third type, social capital, may also strengthen the position of people vulnerable to exploitation, since in-group networks can warn them of exploitative or unreliable employers or landlords. All three types of capital are relevant for the study of skilled Syrian refugees.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF SYRIAN REFUGEES

The conflict in Syria started in 2011 with protests against President Bashar al-Assad, at the time of the Arab Spring. Since then, the civil war has prompted the internal or international displacement of two-thirds of the Syrian population. Some studies also attribute this conflict to climate change (Kelley et al., 2015), which would mean that Syrian refugees are both climate and political displaced persons. More recent research by Sirkeci, Unutulmaz, and Utku (2017: 1-2) attributes the Syrian refugee crisis to what they call the “3Ds of human mobility: demographic deficit, development deficit, and democratic deficit,” all sped up by the civil war, but present in Syria before 2011. Their study finds that the present refugee crisis was preceded by a generalized desire to migrate among the Syrian population that exploded during the later humanitarian crisis.

International efforts were made to de-escalate the conflict and make return a more plausible plan for many Syrians. By May 2017, international intermediaries of the conflict (Russia, Iran, and Turkey) advanced the implementation of “de-escalation zones,” and talks were held on post-war reconstruction and the return of Syrian refugees to Syria (Vignal, 2018). However, in April 2018, the United States, France, and Britain launched airstrikes to punish President Bashar al-Assad for a suspected chemical attack.

To sum up, the conflict has been going on for seven years now and is far from over. The country's infrastructure has collapsed and 85 percent of the remaining Syrians now live in poverty (Vignal, 2018). Ninety-five percent of people lack adequate healthcare and 70 percent lack regular access to clean water. Half of the children are out of school. In 2017, the estimated number of victims since the beginning of the civil war was 470 000 people killed, 55 000 of them children (World Vision, 2017).

Of Syria's former population of 21 million, about two-thirds have left their homes; in 2017, an estimated 6.3 million were internally displaced and 7 to 8 million were international migrants. This scale of population displacement has not been seen since World War II (Nowrasteh, 2016). Previously populated areas have been largely destroyed and emptied of their inhabitants, while others, mostly in the regions held by the al-Assad regime, are now crammed with displaced Syrians (Vignal, 2018).

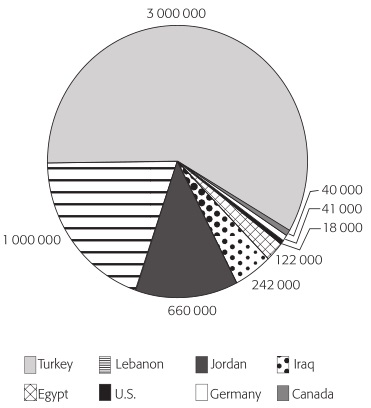

Most of the Syrian refugees are to be found in neighboring countries: with Turkey and Lebanon hosting 3 and 1 million Syrian refugees, respectively (World Vision, 2017; also see Figure 1). The Gulf States host about 1.2 million Syrians on work visas, but they are not legally considered refugees or asylum seekers because those nations are not signatories to the UNHCR commission (Nowrasteh, 2016). At the peak of the European migrant crisis in 2015, 1.3 million Syrians requested asylum in Europe (World Vision, 2017). About 60 000 Syrians were received in North America (World Vision Staff, 2017).

Sources: World Vision (2017); Zong and Batalova (2017).

Figure 1 ESTIMATED NUMBER OF INTERNATIONALLY DISPLACED SYRIANS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES (2017)

Before the war, population surveys in Syria cited an 87 percent Muslim majority, with relevant consequences in terms of economic analysis (Smith, 2016: cxxxvi). As Smith shows, the principles of Islamic finance are to ensure that the few do not accumulate wealth while others suffer; individuals who obey the rules of Islamic finance are presumably community minded and therefore in accordance with the ideals of social entrepreneurship.

As a matter of fact, private business has been a common trend in Syria for many years. In 2011, nearly 35 percent of the Syrian work force was self-employed. By comparison, the United States, home to Silicon Valley and one of the leading hubs for entrepreneurship in the world, had only 6.8 percent self-employment in the same year (Smith, 2016: cxl).

Syrian population demographics contain a number of statistics that reflect the existence of robust human capital. As of 2011, 86.4 percent of the total population was literate, defined as the percentage of the population over the age of 15 who could read and write. Ninety-seven percent of Syrian children were enrolled in primary school, making Syria a leader in education among its peers in the region. Before the war, in the early 2000s, at any given time there were 100 000 Syrians in university, over 6 percent of the population at the time (Smith, 2016: cxliii).

These features are now reflected in the overall characteristics of Syrian refugees. Some studies have identified two generalized profiles of Syrian refugees: poorer, rural workers based in camps in Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon; and richer, middle-class professionals living outside of refugee camps, recently migrating to Europe via Greece and the Western Balkans (Sasnal, 2015). It has thus been assumed that Syrians in Europe come from the richer part of Syrian society, previously employed outside of the agricultural sector (in services, trade, construction, health service, and education), with university studies, economically active, and accustomed to gender equality (Sasnal, 2015: 1). They are also the ones who could afford a trip of thousands of euros to Europe.

Political science professor Barry Stein points out that, “[Syrian] refugees are not poor people. They have not failed within their homeland; they are successful, prominent, well-integrated, educated individuals who fled because of fear of persecution” (Smith, 2016: cxlvii). To be sure, a survey of 305 Syrian refugees in Austria, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (Betts et al., 2017) shows that 38 percent of them had a university education, and one-third had been employed in either skilled work or the professional services industry in Syria. Due to their high educational levels, it has been assumed that they may contribute to the economies of the destination countries. A study by Global Ministries (2018) shows that the main countries receiving Syrian refugees have experienced a growth in their GDP from 2017 to 2018 by 3.5 percent (Turkey), 2 percent (Lebanon), and 3.5 percent (Jordan).

CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED HOST COUNTRIES

Method

I gathered information on the overall conditions of the reception of Syrian refugees in seven OECD countries: Turkey, Germany, the UK, Canada, the U.S., Mexico, and Brazil.2 What follows is a cross-case comparison of the policies on Syrian refugees in these countries, in order to assess various national approaches for dealing with the Syrian CIDSR.

The analysis is structured on five levels of study: a) foreign policies for the acceptance of Syrian refugees; b) domestic policies and national legislation; c) private and not-for-profit initiatives; d) the social and economic composition of Syrian CIDSR; and, e) testimonies of Syrian skilled refugees. These five levels of analysis are not necessarily exhaustive or the most socially relevant, but they are the ones that could be actually used for an equitable comparison, based on the available data in the academic literature, governmental and NGO reports, and media features. In comparison to a multiple case study that would explain each difference by country, I chose to present the analysis according to each variable of study that develops a certain level of analysis.

Foreign Policies for the Acceptance of Syrian Refugees

The seven selected countries have diverse approaches to receiving refugees, and they all signed the 1951 Refugees Convention, except the U.S., which is only part of the 1967 UN Protocol Related to the Status of Refugees. Central to these two agreements is the principle of non-refoulement, that is, no refugee should be returned in any manner to a country or territory in which his or her life or freedom would be threatened. The convention also prohibits the restriction of refugees' rights to go to a third country (Diab, 2017).

According to the Dublin Regulation applied in Europe, the first country where an asylum seeker arrives is responsible for processing his/her application and resettling him/her, which explains the high concentration of Syrian refugees in certain countries like Turkey or Greece. To ease the burden in these two destinations, EU leaders agreed on a voluntary system for sharing and redistributing the refugees (Gilbert, 2017: 24-25).

However, Turkey has been the main receiver of Syrian refugees, admitting 3 million Syrians since the start of the crisis in their country; those 3 million make up 3.5 percent of the Turkish population. Most of the refugees applying for asylum in Europe or North America have first passed through Turkey, a country that acts as a nodal point for conflict-induced displacement.

According to EU rules, after a refugee arrives in the European Union, he or she must wait between six and nine months to be granted asylum (Smith, 2016). This means that the refugees are granted temporary residence permits, but they cannot work till they obtain the status of asylum, which allows them access to work, education, language classes, and the social insurance system. The application process may last for a year, during which the refugees cannot apply for asylum in another country. This procedure was applied by Germany and also by the UK before it announced its exit from the EU.

The majority of the Syrians accepted in Europe are males, half of them under 24, a fact explained by the dangers of human trafficking along the route; this is also described as “asylum Darwinism.” Even though they generally do not speak the language of the country where they arrive, these men are assumed to integrate to the economy and serve to sustain Europe's demographic stability and economic growth. Therefore the acceptance of refugees in general and Syrians in particular, has also been characterized as “an example of economic pragmatism” (Loo, 2016).

A significant proportion of the Syrian refugees, especially the educated ones, who arrive with the biggest cohort to Turkey, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, and other neighboring countries, afterwards apply for asylum in Germany, the country that takes in most of the refugees in the EU. Over the past 30 years, Germany received 30 percent of all the asylum applications in Europe, a greater share than any other country (Loo, 2016). According to the same author, this may be due to Germany's image as a democratic country where laws are respected, but also to the strong Diaspora networks that help reproduce the intake of certain populations, for instance, from the Middle East and African countries like Somalia, Libya, Sudan, Eritrea, or Nigeria. Actually, the German system was criticized for instantly rejecting an important number of Syrian refugees directly at the border, in violation of both the Refugee Convention and the European Convention on Asylum and for shifting responsibilities to Eastern European states, often seen as unprepared or ill-equipped to handle large groups of asylum seekers (Diab, 2017: 91).

Even so, Germany is known as a main destination for refugees in Europe. Between 2011 and 2016, Germany received 41 000 Syrian refugees (Nowrasteh, 2016). By comparison, the UK only resettled 2 898 Syrian refugees by 2016 (Gilbert, 2017), with a more uncertain record of employment. Only 1.1 percent of the Syrian refugees arriving in Germany spoke the language (Nowrasteh, 2016). Despite language difficulties, 73 percent of the Syrian refugees (30 000) were reported to have found a job with a salary that made them subject to social insurance contributions (Knight, 2016). A qualitative analysis of Syrian refugees in Germany actually found that most of them were somewhat or highly skilled (Smith, 2016).

Studies show that the recent intake of refugees after the 2015 has resulted in the biggest population increase in more than 20 years and has boosted Germany's population by more than one percent (Loo, 2016). For instance, Germany has a high percentage of Syrian doctors, who represent the fourth largest group among foreign doctors in the country (2 159 Syrian doctors are said to presently practice in Germany) (Loo, 2016).

While North America received far fewer Syrian refugees than Europe or the Middle East, their characteristics are slightly different from those based in Europe. Among the 26 615 Syrian refugees who came to Canada between 2015 and 2016, a significant segment is of working age (18 years and above), generally male (Magnet Today, 2017). Seventeen percent of the Syrian refugees arriving in Canada have undergraduate or graduate studies. For Toronto, where 6 805 Syrian refugees were settled, the skills figure is even higher: over 55 percent of them come with high occupational skills and experience, according to the same study (Magnet Today, 2017).

The case of Canada presents a singular mixed policy that combines governmental funds with private funds for refugees. As such, 65 percent of the Syrian refugees are privately sponsored, 27 percent arrived through government assistance, and 8 percent through mixed sponsorship (Grant, 2016). While 12 percent of the government-sponsored refugees found work in 2016, more than half of the privately sponsored Syrians, who are also more skilled and tend to have higher rates of university degrees, are already integrated into the job market (CCIRC, 2017).

However, the educational level for almost one-third of the Syrian population in Canada has not been assessed. Syrian families arriving in Canada have an average of five to eight members, much larger than Canadian families. Their integration is more difficult due to the scarcity of large homes and, sometimes, to the fact that only one or two of the family members, generally men, are working.

Canada fulfills a similar role to that of Germany in the North American region. It is more open than the U.S. to receiving refugees for humanitarian purposes, under conditions of low population density and an aging society. In 2015, Canadians over the age of 65 outnumbered those under 15 for the first time, a disproportion that the Canadian government is trying to resolve through its immigrant-friendly policy. In particular, Canada has welcomed Syrian refugees as a “national project” and as part of its longstanding humanitarian tradition (IECBC, 2016). According to Immigration Minister John McCallum, “More immigrants for Canada would be a good policy for demographic reasons” (Mohdin, 2016). Canada´s plan is to increase the intake of economic migrants and skilled workers, who had been blamed in the UK and the U.S. for depressing wages and taking jobs from locals. Canada actually admitted 55 800 refugees in 2016 and 40 000 in 2017. This may be explained by the diminishing flow of Syrian refugees, which reached its peak in 2015 and then dropped.

The Syrian refugees arriving in the U.S. have similar characteristics to those in Canada. Compared to Europe, where refugees are allowed entry into the European countries and then apply for asylum, the U.S. applies an enhanced screening process for all the Syrian refugees entering U.S. territory (Global Ministries, 2018). Of the 18 000 Syrian refugees welcomed in the U.S. since 2011, 25 percent are men escaping terrorists, condemned by ISIS for leaving Syria and rejecting its extremist ideology (Global Ministries, 2018). To prevent terrorism, 27 U.S. states opposed accepting Syrian refugees in 2015.

However, former President Obama approved the entry of 10 000 refugees (Gowans, 2017). One-third of them went to California, Michigan, and Texas, where most of the broader Syrian immigrant population lived (Zong and Batalova, 2017). Half of them were children under 14. Ninety-eight percent of the Syrian refugees resettled in the United States were Muslim and about 1 percent Christian.

Syrian refugees in the U.S. were later banned by President Trump in 2017, who issued one of his first executive orders on refugees and visa holders from designated nations such as Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, and, of course, Syria. While the order was aimed at limiting the entry of terrorist fighters, it also affected real refugees in need of humanitarian aid (Nowrasteh, 2015), who hardly compete at all for jobs with U.S.-born workers (Dyssegaard, Roldan, and Mathema, 2016).

Despite the encouraging characteristics of Syrian migrants in North America and Europe and their traditions as countries of asylum, both Mexico and Brazil have received few Syrian refugees after the 2011 war. In Mexico, only 16 Syrian refugees were registered in 2014, and no information exists about any increase in that number afterwards. Brazil received 400 asylum requests from Syrians in 2016, down from 1 500 in 2014 (Renwick, 2017). Even though their number is so small, many of them find it difficult to get a job, as shown later in this study.

Latin America has indeed been a low receiver of Syrian refugees, but an interesting destination for studying the conditions for South-South refugee resettlement. While Mexico lacks a governmental plan for Syrian refugees, Brazil acts as a transit destination, similar to Turkey, mainly due to the “lack of economic opportunities to convince refugees to permanently call it home” (Renwick, 2017).

The same study by Renwick shows that around 9 000 people have refugee status in Brazil. Syrians make up the largest group, followed by Angolan, Colombian, and Congolese refugees. Since 2010, Brazil has more than doubled its intake of refugees, but their integration into the labor market has been diminishing due to the economic crisis. For instance, 2 700 refugees were employed in the formal sector in Sao Paolo in 2014, but only 371 in 2016 (Renwick, 2017). Many refugees in Brazil work in the informal sector and are vulnerable to exploitation, which means this cannot be the final option for Syrian CIDSR, who may choose to apply for further asylum in Canada, Chile, or Germany.

Domestic Policies and National Legislation

Even though domestic and foreign policies on Syrian refugees are very linked, national programs differ if they are aimed at image promotion, humanitarian human resource management, and brain drain.

Turkey's position as a main refugee receiver has been interpreted by some authors (Hintz and Feehan, 2017) as an attempt to improve its image and “occupy a moral high ground” in the face of European Union. In particular, about 300 Syrian refugees were granted the chance to apply for Turkish citizenship, a program also reinterpreted as a way to revert the brain drain of dissident Turks. According to Hintz and Feehan (2017), “Rather than ending the purge that has targeted over 100 000 academics, journalists, and other educated Turks accused of being involved in terrorist activities, Erdog_an sees their replacements in the Syrians to whom citizenship will be granted. The system being drafted is similar to the points-based systems for migrants in Australia and Canada; through this system only those with the skills to contribute to Turkey's economy will be granted permanent status in Turkey. This plan is intended to mediate Turkey's 'acute shortage' of skilled workers, evidenced by 57 percent of Turkish employers reporting that they experience difficulty in finding workers to fill open positions.”

In general, the legislation available in the cases examined follows the national guidelines, besides the existence of regional agreements, as in the case of the European Union. Turkey is the only country that actually changed its legal framework after the start of the Syrian war. The New Law on Foreigners and International Protection in Turkey (2014) increases legal certainty for asylum seekers and refugees by establishing the rights of the refugee population and giving them the possibility of enforcing those rights in a national court; it also increases the predictability and legality of the administration's decisions. However, the law's enforcement is not always accurate due to Turkey's domestic conflicts and to its governance through executive orders. This situation further complicates cooperation on refugees with other EU countries.

Turkey is at the center of current debates because of its role to prevent refugees traveling to Europe, Currently, Turkey hosts 3 320 814 Syrians (Sirkeci, Unutulmaz, and Utku, 2017: 12). For a more accurate interpretation of Turkish policy on Syrian refugees, it is important to note at least two relevant moments. At first, Turkey had an open-door policy that let virtually all the Syrians into the country and, therefore, no record existed of their entry either (Spilda, 2017). This phase was also accompanied by a warm welcome by the Turkish population, who used to think that Syrian immigration would be temporary. By comparison to European countries, the United States and Australia, refugees were not placed in any detention centers in Turkey (Civelek, 2017) However, a second phase was accompanied by an increasing awareness that most of the Syrian refugees would stay. The issue was also increasingly politicized in Turkey as in the European countries. Refugees in general -and Syrians in particular- became part of a more generalized discourse that considered them an invasion that would abuse the welfare state (Unutulmaz, 2017: 214). This is even more evident in a country like Turkey, where the discourse of diversity has not been popular; on the contrary, “strong republican ideals of a unified nation [are] embodied in the imagination of a modern Turkish citizen” (Unutulmaz, 2017: 227).

For its part, Germany established a process of formal evaluation and recognition procedure for foreign qualifications under a program called “integration by qualification” (Loo, 2016), financed with €2.2 million, available for regular migrants, but also for refugees. The corresponding information is available in Arabic, Dari, Farsi, Tigrinya, and Pashto, the languages most commonly spoken by refugees. People who lack documentation of their studies may undergo a “skills analysis” including the submission of work samples, interviews, or practical examinations.

Other countries such as the UK only have resettlement programs for vulnerable persons, but do not necessarily plan to assess their skills to integrate them into the job market. The UK plans to resettle 20 000 of the most vulnerable Syrian refugees by 2020 (Gilbert, 2017). As the second largest bilateral donor supporting Syrian refugees, the UK Department for International Development has provided more than £2.3 billion in international aid to the Syrian region since 2012 (Gilbert, 2017: 35).

In January 2016, an open letter to the prime minister supported by 120 leading UK economists stressed the economic indicators and arguments for welcoming refugees to the country: “Refugees should be taken in because they are morally and legally entitled to international protection, not because of the economic advantages they may bring. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the economic contribution of refugees and their descendants to the UK has been high” (Gilbert, 2017: 45).

This is different from Canada, where refugees are only screened for criminal backgrounds or health problems. The government created the Syria Emergency Relief Fund and actively cooperates with the private sector for mixed sponsorship of the refugees. However, their labor integration is not a main topic of the Canadian approach. In the words of Senator Ratna Omidvar, “There has been an outpouring of support to welcome Syrian newcomers from all sectors, public and private. But missing was a clear focus on helping them find the right employment to match their skills and capabilities. Skilled immigrants and refugees present a great opportunity for our economy and for employers” (cited in Hire Immigrants, 2017).

The U.S. has offered yet another approach to integrating Syrian refugees, at least before the ban in 2017. The government was working with resettlement agencies to find locations where a previous community of Syrians migrants existed and where jobs and housing would be available. That is, once the Syrian refugees are accepted, the government would take care of their integration. However, with the change of presidency, President Trump depicted them as “compromised by terrorism” and threatened to send them back (Dyssegaard, Roldan, and Mathema, 2016: 1), as previously mentioned.

However bad this discourse may seem, other OECD countries in Latin America generally lack long-term governmental plans to receive and integrate Syrian refugees. Presidential changes also have significant consequences, in Brazil like in the U.S. While former President Dilma Rousseff initiated talks with the EU in 2016 to accept 100 000 refugees in the following five years, the plan was suspended under the administration of Michel Temer (Renwick, 2017). Brazil has a humanitarian visa for refugees, but it offers no resettlement plans for those who manage to pay their way into the country.

In both North America and Latin America, no evidence exists of a change in the national legislations on refugees due to the arrival of the Syrians, except for President Trump's aforementioned ban. No regional agreements exist either, which perhaps partially explained by the lower inflow of Syrians than in Europe and Middle Eastern countries.

Private and Not-for-Profit Initiatives

Few countries manage to involve the business community with skilled refugee integration, despite the fact that their working potential has been noted by various transnational human resource agency reports. In Europe, public-private cooperation for refugees has a good record. For instance, in Germany several website programming courses exist, such as “Refugees on Rails” and ReBoot Kamp, among others, founded by German tech entrepreneurs for refugees who could later find jobs in the technology industry (Smith, 2016). Apparently, Germany may actually need those refugees to fill vacancies in engineering jobs (Smith, 2016). One interesting detail is that refugees who get jobs after taking these courses pay for the course of another refugee, encouraging help and cooperation among the Syrian community itself (Smith, 2016: 58-9). This type of high-tech peer-to-peer economy also facilitates the donation of computers and volunteering activities from the engineers who teach, sometimes using the headquarters of companies like Microsoft and Google.

Apart from high-tech courses, other alternative initiatives exist, such as the Migration Hub, a start-up involving refugees for purposes of social innovation and entrepreneurship, and Kiron University, funded to help refugees finish their degrees. Admission at Kiron is not based on academic requirements, language tests, passports, or residency permits; it even provides each student with a free laptop and internet access. In 2016, Kiron enrolled 2 600 refugees in Germany, 80 percent of whom were Syrians (Loo, 2016).

A similar initiative is the Refugee Career Jumpstart Project (RCJP), a Canadian non-profit focused on streamlining the process between refugees' arrival and their employment, with an excellent response during its fundraising campaign in big Canadian cities (Hire Immigrants, 2017). Other initiatives are oriented toward skilled refugees but are not tethered to any country in particular, but work globally. One is “Talent Beyond Boundaries,” which received 8 000 applications from skilled refugees -mainly Syrians at the moment- who aim to be hired by companies around the world (McGhee, 2017).

By contrast, Latin American initiatives have little support from the private sector, with the exception of the Habesha project, a locally-based NGO designed to select an elite group of Syrian students from diverse regional and academic backgrounds to study in Mexico. Since its foundation in 2015, the organization has managed to enroll 14 Syrian students in Mexican universities. This project carefully selects the recipients it supports, who have to be recommended by an international institution and then pass through rigorous background and health checks. “We choose them like little pearls, and we take care of them so well. We make sure that today there's a psychologist and tomorrow there's a mathematics professor. And finally they will go to universities that 99 percent of Mexicans would like to attend,” says project coordinator Adrian Meléndez (Weaver, 2017).

Social and Economic Integration of the Syrian CIDSR

Integration problems of Syrian CIDSR seem to be similar in all the countries covered by this study, such as limited knowledge of the language, truncated professional networks, and often poor physical or psychological health (Smith, 2016). These barriers were even higher for women, who generally lacked work experience. Due to prejudice, discrimination, and difficulty in recognizing credentials, many of the skilled had had only limited economic participation in their host countries. With time, this may lead “individuals to lose their capacity for skilled employment” (Smith, 2016: 52).

The conditions of reception are quite different depending on each country and refugees' economic status. While Turkey certainly hosts a huge number of Syrians, they are not necessarily offered the best living conditions in the camps, unless they come from well-off families who can afford to pay rent and for their children's education. An estimated 10 percent of Syrian refugees live in camps and the ones outside only register to get access to social services (Spilda, 2017: 54).

While in the early years of the Syrian crisis the Turkish population welcomed the refugees, with time, problems started due to their unsuccessful integration and uncertain status. Previous research shows that Syrians currently in Turkey have set up 4 000 businesses (Hintz and Feehan, 2017), thereby helping boost the country's economy. The problem of integrating the Syrian refugees in Turkey began with the closure of borders by several European countries, which determined that many refugees would stay in Turkey. At the same time, Syrians in Turkey complained about the issuance of few work permits. This, in turn, caused a change of attitude in the Turkish population, at a time of high domestic political instability that led to constant change of personnel in government institutions. At the peak of the Syrian crisis, normal legislative procedure was replaced by legislation by presidential decree.

Paradoxically, being skilled may be a problem for the Syrian refugees, as the European Union might want to take them in, while Turkey is trying to prevent them from leaving the country (Demircan, 2016; Hintz and Feehan, 2017). The UN refugee agency in Ankara declared that they were “aware that the Turkish government has, in some cases, applied educational criteria when issuing exit permits to Syrian refugees selected for resettlement outside Turkey.” However, the Turkish government denied this. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu stated, “We are against the selective approach to resettlement. No one can say 'I want to get the Christians; I want to get the best educated ones, the [able-bodied] ones and not the disabled.' A selective approach is not humane. You cannot select people like you select sheep and goats at the market” (cited in Feldman, 2016).

Even when the German government accused Turkey's administration of bad practices, the arrival of Syrian refugees in Germany also brought problems. Some of the shortcomings of the skills assessment process in Germany have been its concentration in the fields of teaching, engineering, nursing, and medicine, as well as its excessive formalization, incompatible with a very fast process of expulsion and the differences between the educational systems of Syria and Germany (Loo, 2016).

However, the social integration of Syrian refugees has been object of state policies in Germany, where the native population has been trained by the principles of the Willkommenskultur (the welcoming culture). Syrian refugees were offered cheap language classes, and citizens were called upon to help them and make them feel welcome (Smith, 2016: 41).

The German government also promoted the use of social entrepreneurship to integrate Syrian refugees in an increasingly multicultural context that could “enhance the competitiveness of Germany's economy” (Smith, 2016: 43). According to the results of Smith's fieldwork (2016), among the Syrian refugees in Germany are many professionals with higher education and multilingual training, whose main desire is to be reunited with their families.

By comparison, the Syrian refugees in the UK arrive with a vulnerability assessment by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Turkey, Jordan, or Lebanon. In the UK, aid is administered locally, and refugees are provided with housing, educational services, safety briefings, and orientation. The vulnerability assessment prioritizes those refugees who cannot be supported effectively in the Syrian region, such as women, children, the elderly, victims of torture and sexual violence, and the disabled. This leads me to conclude that the refugees who make it to the UK are not necessarily the most skilled but the most vulnerable. The selection is based mainly on humanitarian considerations.

Refugees in North America have faced similar integration problems, and many are still unemployed after more than a year in Canada or the U.S. “While Canada has won praise for its warm welcome of newcomers, experts see room for improvement in smoothing their transition into the work force” (Grant, 2016). Canada has a mixed system of selection for government assisted refugees (GAR) and privately sponsored refugees (PSR). The former are accepted exclusively based on humanitarian concerns, like in the UK. GARs have larger families than PSRs, sometimes of up to 14 persons, and 60 percent of them are children 14 or younger (CHEO, 2016). Two-thirds of them do not speak English or French. This means that for Canada, GARs would be more of a humanitarian investment at the moment than a medium-term economic scheme. By comparison, privately sponsored refugees, who often have advantageous family networks and higher educational levels, tend to integrate better economically and socially. Syrian refugees, be they GARs or PSRs, normally go to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, the three largest cities and main receivers of migrants in Canada. However, on a per-capita basis, it was the mid-size Canadian cities that saw the greatest proportional impact of the Syrian refugee flow (Friesen, 2016).

While Syrian refugees have benefitted from two entry options in Canada, their situation in the U.S. has been quite different. They were only received through governmental programs and their integration to the U.S. society has been obstructed by a distorted image of what Syrian migrants are. Some common beliefs were that the Syrian refugees are welfare-dependent and will be a drain on economy, when actually the Syrian population in the U.S. has proven to be even more entrepreneurial than the native-born (Global Ministries, 2018). In the U.S., some Syrian men stated they were dependent on welfare because of bad health conditions or because, if they worked, they would be offered a minimum-wage job. As heads of households, men are more under pressure than women to find work. “[English] classes are mandatory, but they tell us work is also mandatory,” says a refugee in the U.S. (Frej and Abdelaziz, 2017).

Nevertheless, Syrians' profile in the U.S. is quite promising. Although Syrian refugees represent a new flow to the United States, a small Syrian immigrant community has been residing there since the late nineteenth century. As of 2015, approximately 83 000 people born in Syria resided in the United States, accounting for less than 0.2 percent of the overall foreign-born population of 43.3 million (Zong and Batalova, 2017). This small community of Syrian immigrants has higher educational and English proficiency levels than the overall foreign-born population, according to the same authors, since 39 percent are college graduates, as opposed to 30 percent of the U.S.-born. In general, Syrian women have relatively low work force participation, but 49 percent of the Syrian men in the U.S. are employed in high-skilled occupations, for example, managerial, business, and science positions (Global Ministries, 2018). This means that Syrian refugees, both men and women, will be integrated into a highly competitive Syrian community and their contribution to the U.S. economy promises to be high.

The aforementioned Zong and Batalova study (2017) shows that Muslim immigrants in general have been better integrated into U.S. society than in many Western European countries, where many report feeling marginalized and alienated. This is also the case in Latin American countries, as the last section of testimonies shows.

Testimonies of Syrian CIDSR

This final part of the article has the purpose of revealing how re-skilling and de-skilling affects the integration of Syrian professionals. In this respect, the testimony of many skilled Syrians in the selected countries illustrates similar problems.

First, they talk about the need to deal with smugglers to get to a safer place in a neighboring country or in Europe, about the uncertainty of their future, and their fears regarding returning to Syria for the moment. For instance, Essa Hassan (29), a Syrian student hosted by Mexico, does not know when and if he will return to Syria. In the meantime, he plans to study a master's in social engineering and make a contribution in Mexico. “When you see the blood, you know it's not going to end any time soon.…The first goal for me really is to give something back” (cited in Zissis, 2018). Similarly, Syrian professionals interviewed in various countries appreciate the opportunity of having escaped, of being alive, and are thankful to the county that received them “If I'm looking toward the future…, there is dignity [in the U.S.].…At the end of the day, they did give us health care. I want to work so I can pay taxes, to thank this country” (Taqi, chef, interviewed by Frej and Abdelaziz, 2017).

Secondly, they recall the difficulties in finding a job, despite their previous experience in Syria and extra courses in the country of arrival. In particular, I recall the case of Adnan Almekdad (interviewed by Grant, 2016), a former veterinarian owner of an animal clinic back in Syria, former manager and strategist at several pharmaceutical start-ups, and the author of two books. Adnan now lives in Canada with his wife and three daughters and has made friends and learned English, but could not find a job after a year as a refugee. “I am skilled. I have experiences in working, management, [and] manufacturing processes. It's hard.”

Syrian CIDSR demonstrates the high costs of translation of professional degrees, which most refugees cannot pay. For skilled refugees, not having employment is a complete obstacle in the integration process; therefore, in their cases, labor integration may determine the path for cultural and social integration as well. “I want to find a job before the end of the first year, because it's a long time to sit and wait. Canada means many things to me, and one is to find a job or a business....You know, you don't feel like a citizen if you don't have a job; you don't belong” (Almekdad cited in Grant, 2016).

Thirdly, long wait periods for a skilled job de-skills people, as big gaps in their resumes are negatively interpreted by the employers, even though many appreciate that with time, they have acquired resiliency and adaptability. In order to reactivate their skills and fight employers' prejudices, refugees who have been inactive for a number of years may have to train again and strengthen their resumes (Gilbert, 2017).

Fourthly, the desire to integrate is quite high, even at the price of a temporary distance from the Syrian culture and community abroad. Contrary to the U.S. experience, where Syrian refugees are resettled within the Syrian community, in Canada, they manifest a wish for integration even at the cost of not being with their own. Says Richard, a former medical doctor in Syria, now in Canada, “I think if you're going to be Canadian, you should be with Canadians, act like a Canadian, speak like a Canadian. And be friends with Canadians.... If you want to be successful in this country, you have to stay outside your community, and work with other communities and with other cultures” (interviewed by Hire Immigrants, 2017).

Lastly, Latin American countries like Brazil and Mexico seem to be more open and tolerant toward the refugees, in contrast with other OECD economies where Syrian migrants are already seen through stereotyping lenses. Says Mexican Habesha project coordinator Melendez, “There are no stereotypes about Syrians here. There are no stereotypes about Muslims. So it's very easy for them to come, and people will be welcoming. It means we're able to create our own narrative about Syria, about Islam about Middle East cultures because we don't have one” (cited in Zissis, 2018).

Apparently, Latin American countries may also serve as alternative destinations for skilled refugees rejected by European countries. Says Saeed Mourad, a former orthopedic surgeon in Syria, now running a restaurant in Sao Paulo, Brazil, “At first I thought we'd go to England, where I [studied medicine], but they didn't accept me.…We brought our own money with us. I will never [have to] live in a camp or a tent. Not all refugees can do what I did, because they don't have the money. If the war stopped today, I would be in the first line to go back to Damascus.” At the same time, he would prefer to be in the U.S. with one of his sons, but he knows he will not get a visa under the Trump presidency (cited in Renwick, 2017).

CONCLUSIONS

The study of both skilled and unskilled Syrian refugees imposes a return to the theoretical perspective of Diasporas in the original understanding of the concept, that is, displaced people driven abroad by multiple traumas of departure. As such, I propose the study of Syrian refugees as a necessary change of framework from economically-induced skilled migration to conflict-driven migration.

My main findings involve the conceptual differences between conflict-induced and economically-induced displacement of the skilled, as well as international cooperation for skilled refugees. Globalization allows the coexistence of cosmopolitan migrants working in transnational companies who reject belonging to one nation in particular, along with the vulnerability of refugees who would like to belong to any country. At one extreme, we have those who have a nationality and a steady place to live but reject being stable; at the other, we have professional refugees who do not have a country to live in, but would like to put down roots again. Both are skilled migrants; they just belong to different national backgrounds. Some seem to have been born in unluckier places.

Even when the economic explanation of skilled migration has overshadowed the humanitarian one, it is necessary to study both patterns to understand the displacement of the skilled. Compared with planned migration, CIDSR lacks clear spatial and temporal limits: migrants do not know when and if they will return to their homes; and they do not really get to choose their countries of destination, but go where they are accepted. Certification processes are also more complicated in the case of CIDSR: as many of the skilled refugees do not bring their diplomas, and they have not studied the language of the destination country in advance. Therefore, CIDSR is accompanied by a double process of de-skilling and re-skilling, in which refugees have to reinvent their lives and careers.

From the point of view of international cooperation, regional policies toward refugees in general -and skilled in particular- are few, if any. This makes it impossible to coherently compare North America and Europe, but also leaves space for regional agreements and cooperation on CIDSR.

While evidence does exist of Syrian CIDSR being used for human capital purposes in certain countries with aging demographics (Germany and Canada) or to solve previous domestic brain drain problems (Turkey), Syrian refugees tend to be selected based on humanitarian purposes, rather than on their skills. All the countries included in this study, but perhaps more explicitly in the case of Turkey, want to position themselves as places that welcome foreigners, as “moral powers” as opposed to the anti-migrant discourse promoted by right-wing parties in the U.S. and Europe.

Even so, this overall survey of the policies for Syrian CIDSR in selected OECD countries has proven the need for better labor integration policies for skilled refugees that would benefit both the individuals and the destination countries. As opposed to brain drain produced by economic migration, better work opportunities for skilled refugees do not affect the countries of origin more than the damage caused by exile itself.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)