INTRODUCTION

Two main mega-trends of the twenty-first century, economic globalization and rising inequality, have encouraged the mobility across national boundaries and jurisdictions of people with different levels of income and wealth. At one end of the spectrum we find the mobility of labor in search of higher wages and better employment opportunities abroad. As we move up in the ladder of skills and qualifications, talent is internationally mobile: this includes people with special skills and advanced human capital, such as outstanding professionals, executives, academics, artists, writers, and people in the entertainment sector and sports (Solimano, 2008, 2010). A new, related field, is the global mobility of the wealthy, or “high-net-worth individuals (HNWIS),” often defined as people with net assets above US$1 million. The pyramid of HNWIS also includes multi-millionaires, ultra- HNWIS, and billionaires (see section 2 for operational definitions). This is a small, but economically powerful, elite: they represent less than 1 percent of the total world population but control nearly 45-50 percent of the world’s total household wealth.

The wealthy face at least two critical decisions: a) where to reside (including their families), and b) in which countries and what instruments to place their wealth in. Competing investments include company shares, residential and commercial property, bonds, works of art, gold, and other valuable commodities.

The geography of big wealth creation and circulation matters. In the last few decades, large fortunes have been accumulated in Russia, China, India, Latin America, and Africa. Given the history of instability and potential for confiscation (real or imaginary) in these countries and regions, the very rich are starting to establish their residence in high-income nations. A main goal of this mobility is to protect their assets in countries with sophisticated financial systems, well-enforced property rights, good educational facilities for their children, and cosmopolitan cities. With the proliferation of investment migration schemes, the wealthy enjoy special advantages for acquiring permanent residence and citizenship in the host country in exchange for capital contributions to special government funds, the acquisition of real estate, and opening bank accounts in the receiving countries. Thus, the migration of the wealthy is not really motivated by the desire to access better jobs abroad as in the case of migrating workers or talent, but is geared to protecting assets and family and enjoying First World amenities (safe neighborhoods, good schools, efficient public transportation systems, and the ample availability of cultural activities and sports). The level of income and wealth taxes and the cost of enforcement in the host country also matter in the decision to move from one country to another.

The wealthy can also enhance their international mobility by engaging in investment migration programs in “exotic countries,” often small islands and independent jurisdictions, that enable them to acquire the nationality of countries with low or no income taxes and, importantly, to access a large number of countries without a visa. In fact, a citizen of, say, the Caribbean islands of Saint Kitts and Nevis, in exchange for a certain investment of around US$500 000, receives a passport that entitles the holder free-visa entry to 152 countries; a citizen of Cyprus, an EU-member state, has access to 172 nations without a visa.1 At the same time, the direction of this mobility is not only from the core to the periphery; we are also witnessing outflows of the wealthy from traditionally receiving locations such as London and Paris because they want to escape taxation and, at times, terrorist activity that is starting to affect also these privileged cities.

This article examines the main push and pull factors behind the growing phenomenon of the international mobility of wealthy individuals, including the impact of taxation, the role of economic and political instability, violence, the migratory regime, and inequality. In addition, I provide recent figures for the size of the HNWI pool and its patterns of international mobility across countries and cities. The article also briefly discusses differences between mass and elite migration in terms of their impact on the host country in areas such as the labor market, access to social services, and differentiated migration rules for those endowed with capital compared to those who bring mainly their labor power. It also highlights the potential impact of inflows of the wealthy on the price of real estate (making preferred city locations more expensive for locals) and the potential for corruption of local political and policy elites (Nagy, 2017).

THE GLOBAL WEALTHY AND THE RISE OF INEQUALITY

The wealthy are often defined by their net asset holdings (assets minus debt); these definitions can be also complemented by their income flows. Some operational definitions are used in the emerging literature in the field, largely connected with wealth-management companies. Besides HNWIS, we find multi-millionaires (net worth over US$10 million), billionaires (net worth over US$1 billion; and new world wealth (NWW, 2018). Other definitions are ultra-net-worth individuals with net wealth of over US$50 million and demi-billionaires for those with net worth over US$500 million (Shirley, 2018).

Personal wealth can be accumulated from individual savings, inherited from parents, acquired through privatization processes, or grabbed through non-transparent or openly illegal means. Wealth increases when it earns a positive return (flow of income) when invested in the capital market, real estate, art work, or a productive enterprise. In general, wealth tends to be much more concentrated than income (wealth Gini coefficients are systematically higher than income Gini coefficients [Solimano, 2017]).2

In 2017, an estimated 36 million HNWIS existed worldwide, 31.3 million of whom had net assets between US$1 million and US$5 million; nearly 150 000 “ultra-HNWIS”; 5 700 demi-billionaires; and 2 252 billionaires (Credit Suisse, 2017). It is apparent that we are in the presence of a rapidly shrinking pyramid of HNWIS that control a large share of personal global wealth (see Table 1).

Table 1 GLOBAL INDICATORS OF WEALTHY INDIVIDUALS (2017)

| Millionaires (HNWIS) | 36 million |

| HNWIS with net worth between US$1 million and US$5 million) | 31.3 million |

| Ultra-HNWIS (net worth over US$50 million) | 148 200 |

| of which: | |

| Ultra-HNWIS with net worth over 100 million | 54 837 |

| Ultra-HNWIS with net worth over 500 million | 5 749 |

| Number of billionaires (net worth over U$1 billion) | 2 232 |

| Share of HNWIS in: | |

| World adult population | 0.7% |

| Total household wealth | 45.9 % |

Source: Developed by the author using data from Credit Suisse (2017).

Geographically, the millionaires (HNWIS) are concentrated mostly in the United States, home to 43 percent of the world’s millionaires. The next country, but with a much smaller percentage, is Japan with 7 percent of the total, followed by the United Kingdom (6 percent) and France, Germany, and China (with 5 percent each).

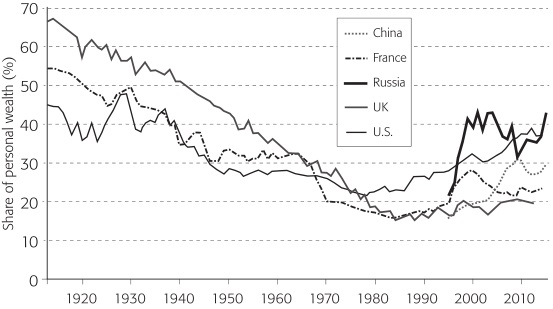

During the twentieth century, personal wealth inequality in advanced capitalist countries followed a sort of U-pattern (see Figure 1): initially, it declined from 45-65 percent in 1913 to 20-30 percent in the 1970s in the U.S., the UK, and France, followed by a tendency of this share to increase. The period of declining wealth concentration includes the two World Wars, the interwar years, and the golden age of capitalism after World War II to the early 1970s. However, in the last third of the twentieth century, the wealthy’s share began to increase sharply in the United States, coinciding with Ronald Reagan’s neo-conservative revolution in the early 1980s, a trend that continued during Democratic Party governments in the 1990s. In fact, the richest people’s share in the U.S. roughly doubled from close to 20 percent in the late 1970s to nearly 40 percent in 2013. The trend toward higher wealth inequality in the United States was well above that of other advanced capitalist nations. In the United Kingdom, the richest 1 percent of the population’s share of the wealth also increased beginning with the Thatcher conservative government, reversing its previous downward trend experienced during a part of the twentieth century; however, it remained substantially lower than the top richest sector’s share in the United States (it stabilized at around 20 percent in the period 1980-2015). In France, a surge occurred in the mid-1990s in the top wealthiest’s share and declined afterwards, stabilizing at a higher level than its historical record (see Figure 1).

Source: www.wid.world (2018)

Figure 1 RICHEST 1% SHARE IN THE WEALTH ACROSS THE WORLD (1913-2015) THE FALL AND RISE OF PERSONAL WEALTH INEQUALITY (SELECTED COUNTRIES)

The trends towards higher wealth concentration took place not only in core capitalist countries in the last third of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century, but also in former communist countries such as Russia and China. Beginning in the mid-1990s, in Russia the top 1 percent of the population’s share of the wealth went up from close to 20 percent to near 45 percent in 2015 (a jump somewhat similar to the huge increase in the United States). In addition, since the 1990s, the richest 1 percent of the population in China has substantially increased its share of the wealth (Figure 1). The egalitarian wealth distribution of their socialist periods was reversed in the last two decades with the advent of oligarchic capitalism in Russia and state capitalism in China.

INTERNATIONAL MOBILITY AND MIGRATION OF THE WEALTHY

The global age makes it far easier for the wealthy (a small group) to migrate than for the working poor (mass migration) through the use of investment migration regimes. Free market economist Gary Becker (1987) argued decades ago that letting immigrants pay for the right to reside in another country (say for obtaining visas and/or eventually residence) was more efficient than subjecting them to lengthy waiting periods for obtaining residence permits and/or citizenship rights. In turn, other authors, such as Surak (2016), Sumption and Hooper (2014), and Prats (2017), examine various dilemmas involved in the market for visas and citizenship rights driven by monetary contributions, noting that rights should not be treated as a commodity to be traded in a market. In a market for visas and nationalities, the wealthy have an advantage: their substantial wealth provides them with a critical advantage for obtaining residence permits and citizenship and enjoying the superior living standards of rich nations. In contrast, foreign workers and poor migrants cannot generally afford hefty payments to obtain visas. Existing income and wealth inequalities are clearly reflected in prevailing migration policies.

WHY DO THE WEALTHY EMIGRATE? PULL FACTORS

Historically, extremely wealthy individuals, including entrepreneurs and rentiers, have moved internationally for at least three reasons: a) in response to new opportunities for obtaining good profits abroad; b) to escape political or ethnic persecution and nationalization policies; and c) to shield their assets from taxation and financial uncertainty in their home countries.

The financial empire built by the Rothschild family in the nineteenth century required an important degree of international mobility of those at the helm of the family business.3 In turn, successful entrepreneurs such as Mellon, Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Soros, and others migrated to the United States where their careers and fortunes (including philanthropic activities) received a big boost (Solimano, 2010). On the other hand, in several countries during the twentieth century, the wealthy left home at the time of anti-capitalist revolutions. That was the case of the 1917 Russian Revolution, in which the Russian wealthy went mainly to Europe to escape the Bolsheviks. The 1949 Chinese Revolution also led Chinese economic elites to leave mainland China and settle in other parts of Asia, where they became important engines of entrepreneurial activity; and the 1959 Cuban Revolution prompted a massive exodus of the wealthy and upper middle class, chiefly to the United States. In recent decades, the threat of socialism evaporated and global capitalism consolidated (albeit with a high incidence of economic crises), which has favored the free migration of the rich. The risks for the wealthy did not disappear, but shifted from socialism and the possible nationalization of their assets to other causes such as terrorism and financial uncertainty. Migration theory (Solimano, 2010) and attitude surveys conducted by wealth management companies highlight the following list of factors that can be relevant for high-net-worth individuals in choosing a country to establish a residence for themselves and their families:

Personal safety;

Availability of high-quality health services;

Favorable tax treatment;

Protection of wealth and property rights;

Good educational opportunities for the children;

Visa-free mobility to third countries; and

Cosmopolitan settings and good transportation connections.

Analysts have developed the concept of a “global market of nationalities,” in which governments compete with each other to attract a small elite of wealthy, people in sharp contrast with the bureaucratic procedures applied to unskilled migrants often coming from developing countries.4 This shows the asymmetrical nature of the “global market for nationalities,” in which the very rich face much more favorable immigration rules than middle-class and working-class immigrants.

In the market-of-nationalities framework, a “Quality of Nationality Index, QNI” (Kochenov, 2016) ranks countries in terms of levels of economic and human development, internal peace, and political stability; visa-free access to third countries (freedom to travel); ability to work without permits and special visas (freedom of settlement); and the quality of the legal system. Interestingly, the index gives considerable weight -as a very valued trait by prospective immigrants- to the fact that holding citizenship of certain countries (for example, member nations of the European Union) enhances the ability to travel without restrictions to other nations.5 Another feature of a preferred host country is the ability to place assets in a safe environment, although the physical location/destination of the rich may not necessarily coincide with the location of their assets. The latter often go to “fiscal paradises” such as the Cayman Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Switzerland, Panama, Jersey Island, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Macau, which offer discretion/secrecy to the holders of bank accounts and property and establish low taxes (or no taxation at all) on yields of assets and other sources of income of foreign depositors (Solimano, 2017).6 Also, wealthy migrants take into consideration countries with well-developed banking systems, currency and capital convertibility, adequate legal services, predictable policies, and “capital-friendly” tax structures when choosing a place to settle.

WHY DO THE WEALTHY LEAVE THEIR HOME NATIONS? PUSH FACTORS

In general, economic insecurity, cumbersome taxation systems, lack of adequate protection of property rights, political uncertainty, austerity policies, depressed asset prices, violence, and terrorism are factors that induce the rich (and the non-rich) to leave their country of residence.

A telling case is Russia where a large number of multi-millionaires (often former enterprise directors during the communist period) were created in a short period after the abolition of the Soviet Union. The new oligarchs moved fast and grabbed valuable state assets through insider’s privatization -a sort of “post-socialist accumulation by dispossession”-, opening the door for private wealth accumulation on a large scale. Nowadays, this new oligarchic class has a strong presence and wields a great deal of influence in contemporaneous Russian society.7 These developments led, among other things, to the worsening in income and wealth distribution indicators in Russia.8

The Latin American case can be also illustrative of the formation of economic elites following privatization and free market policies in the 1980s and 1990s (Solimano, 2016). Historically, in the colonial period, inequality in the region was associated with concentrated patterns of land ownership (including underground gold and silver deposits) allotted by the Spanish crown to its delegates and local oligarchies of Spanish descent. More recently, land ownership was replaced by an unequal distribution of financial assets, capital, and natural resources such as copper, oil, tin, rubber, and others as the main source of overall inequality. Current estimates of Gini coefficients for net personal wealth yield numbers in the range of 70-80 percent for some developing countries such as Chile. Even more concentrated is financial wealth, with the financial-assets-Gini coefficient climbing to 90 percent.9

High inequality, though benefitting the wealthy, can also induce the rich to leave their home countries (or at least place part of their assets abroad), since unequal societies are more prone to experience macroeconomic and financial crises and cycles of populism and authoritarianism. In contrast, these cycles are rarely observed in more socially cohesive and egalitarian societies (for example, the Scandinavian and Central European nations).10 This favorable combination of social attributes often encourages the rich to remain at home (see below).11

Another set of factors that can trigger the flight of people and capital are violence, terrorist activity, and taxes. France had outflows of HNWIS coinciding with the Paris terrorist attacks of late 2015 and the Nice attack of July 14, 2016. A similar situation can be seen in Turkey, which is also experiencing outflows of HNWIS (see Table 3 below), affected by terrorism and heightened Islamic fundamentalist activity. In the Latin American context, in Venezuela, economic collapse since 2014, with hyperinflation, scarcities, and massive output contraction, has prompted the wealthy and large segments of the population, such as professionals and middle-class and working people, to leave the country.

Table 2 COUNTRIES RANKED BY HNWI INFLOWS (2017)

| Country | Net inflows of HNWIS in 2017 |

|---|---|

| Australia | 10 000 |

| United States | 9 000 |

| Canada | 5 000 |

| United Arab Emirates | 5 000 |

| Caribbean* | 3 000 |

| Israel | 2 000 |

| Switzerland | 2 000 |

| New Zealand | 1 000 |

| Singapore | 1 000 |

* Caribbean includes Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Virgin Islands, St. Barts, Antigua, St. Kitts & Nevis, etc.

Note: Figures rounded to nearest 1 000.

Source: NWW (2018).

Table 3 COUNTRIES RANKED BY HNWI OUTFLOWS (2017)

| Country | Net outflows of HNWIS in 2017 |

|---|---|

| China | 10 000 |

| India | 7 000 |

| Turkey | 6 000 |

| United Kingdom | 4 000 |

| France | 4 000 |

| Russian Federation | 3 000 |

| Brazil | 2 000 |

| Indonesia | 2 000 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 000 |

| Nigeria | 1 000 |

| Venezuela, RB | 1 000 |

Note: Figures rounded to nearest 1 000.

Source: NWW (2018: 24).

High taxes can also prompt the rich to leave home but not in all countries. In 2014, prominent French actor Gerard Depardieu was granted Russian nationality following his desire to stop paying what he considered high taxes in his home country. A number of wealthy (and middle-class) U.S. Americans, mostly living outside the U.S. and holding other nationalities, have relinquished their U.S. citizenship in recent years. Interviews highlight that a main motivation for doing so is not so much a very high level of taxation but the complexity of the U.S. tax system, including the high cost of filing taxes every year outside the U.S. where tax experts conversant on that tax system are in short supply. Concerns about the invasion of privacy on asset holdings by U.S. tax authorities are also reported to be another cause for relinquishing U.S. citizenship (Durden, 2014). On the other hand, countries with a high level of personal taxation such as the Scandinavian countries do not figure prominently among the nations whose rich nationals depart from their home countries (see below). Therefore, the relationship between the level of taxation and the departure of the very rich is not that straightforward. The rich may not like paying high taxes but if they receive, like any other citizen in universal systems of provision, good quality social services like education for their children, health services, pensions provided by the state and funded with income and wealth taxation as in the case of Scandinavian countries, the rich (and the non-rich) may decide to stay at home.

Statistical Estimates of Migration of the Wealthy

The international mobility of wealthy individuals has been increasing in recent years.12 In 2017, nearly 95 000 HNWIS moved to reside abroad compared to 82 000 in 2016 and 65 000 in 2015 (NWW, 2018). As the total stock of migrants is nearly 250 million, we are speaking of a very small group of individuals worldwide, but with a large command of financial resources (see next section).

The wealthy are benefitting by having second nationalities: an estimated 34 percent of HNWIS globally have a second passport/dual nationality. This percentage is the highest for wealthy Russians/CIS (58 percent), followed by wealthy Latin Americans (41 percent), and wealthy individuals from the Middle East (39 percent). Asians and Australians have the lowest percentage of second passports/dual nationality (Shirley, 2018; Fernandes, 2017).

Inflows and Outflows

The three most preferred country destinations for HNWIS in 2017 (countries with net inflows of HNWIS above 1 000 individuals) were Australia, the United States, and Canada, followed by the United Arab Emirates and small countries in the Caribbean such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, the Virgin Islands, St. Kitts and Nevis, and others (Table 2).13

In turn, a list of 11 countries with the largest net outflows of HNWIS in 2017 (Table 3) is headed by China and India -the scale factor has to be considered here- followed by Turkey, France, the United Kingdom, and Russia. It is quite remarkable that two advanced countries like the UK and France appear with significant net outflows. Two Latin American countries, Brazil and Venezuela, both affected by serious economic and political crises, are among the top ten countries with the largest outflows of HNWIS.

The main cities that received inflows of more than 1 000 HNWIS in 2017 were Auckland, Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Tel Aviv, Dubai, San Francisco, Vancouver, and others (Table 4). It is worth noting that Canada and Australia have concentrated large inflows of HNWIS in recent years. In contrast, cities that experienced outflows of more than 1 000 HNWIS in 2017 were Istanbul, Jakarta, Lagos, London, Moscow, Paris, and Sao Paulo (Table 4). Some of these cities display the typical factors that encourage the exit of people from their home countries/cities, such as violence, terrorism, high taxes, pollution, and traffic congestion; nonetheless, cities such as Paris and London that have traditionally been preferred destination for the wealthy now show positive net outflows of wealthy individuals. The reasons for these reversals are related to incidences of violence such as rape, terrorism, attacks on women, religious tensions, and anti-Semitism.

Table 4 CITIES WITH LARGE (1 000+) INFLOWS OF HNWIS (2017)

| City (alphabetical) | Country |

|---|---|

| Auckland | New Zealand |

| Dubai | uae |

| Gold Coast | Australia |

| Los Angeles | U.S. |

| Melbourne | Australia |

| Montreal | Canada |

| Miami | U.S. |

| New York City | U.S. |

| San Francisco Bay Area | U.S. |

| Seattle | U.S. |

| Sydney | Australia |

| Tel Aviv | Israel |

| Toronto | Canada |

| Vancouver | Canada |

Source: NWW (2018)

In turn, it seems that the level of inheritance taxes in the UK and France (over 40 percent) also acts as a deterrent for the very rich (NWW, 2018).

Bilateral corridors (see Box 1) include wealthy Chinese going to the U.S., the UK, and Canada; wealthy Indians going to the U.S., the UAE, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand; rich Britons going to Australia and the U.S.; wealthy Russians moving to the U.S., Cyprus, Switzerland, the UK; the French going to Canada, Switzerland and the U.S.; Brazilians going to Portugal, Spain, and the U.S.; Venezuelans going to the U.S., and so on. The countries of origin are widely diverse and include emerging economies and post-socialist, post-statist countries as well as advanced economies. Destination nations include mature advanced capitalist economies (the U.S., UK, Switzerland, and Australia) as well as Southern European nations like Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, and small islands in the Caribbean.

Box 1. Main Corridors for the Wealthy

Chinese HNWIS moving to the U.S., Canada, and Australia

Indian HNWIS moving to the U.S., the uae, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand

Turkish HNWIS moving to Europe and the uae

UK HNWIS moving to Australia and the U.S.

French HNWIS moving to Canada, Switzerland, and the U.S.

Russian HNWIS moving to the U.S., Cyprus, the UK, Portugal, and the Caribbean

Brazilian HNWIS moving to Portugal, the U.S., and Spain

Indonesian HNWIS moving to Singapore

Saudi HNWIS moving to the UK, France, Switzerland, South Africa, and the uae

Venezuelan HNWIS moving to the U.S.

Source: NWW (2018)

HNWIS by Country and City

Let us turn to the number of HNWIS inhabitants per country and city rather than yearly flows. The country with the largest concentration of HNWIS (including multi-millionaires and billionaires) is the United States (with around 5 million), followed by Japan (1.3 million), China (877 700), and the UK (826900) (Table 6). For the case of multi-millionaires and billionaires, the second main country of origin/residence is China, followed by the UK for multi-millionaires and India for billionaires. In 2017, New York had the largest number of HNWIS (393 500), followed by London (353 600), and Tokyo (321 800) (Table 7). These three cities boast a prime property market and cosmopolitan environments and have highly developed financial systems. They are followed by Hong Kong, Singapore, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Los Angeles (all in the range of 200 000 to 250 000 HNWIS), while Chicago, Beijing, and Shanghai each has over 250 000 HNWIS. New York is also the city with the greatest concentration of multi-millionaires, followed by London and Hong Kong. For billionaires, New York is followed by Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai. Despite the net outflows of HNWIS (see Table 5), both London and Moscow are still high on the world ranking of resident billionaires.

Table 5 CITIES WITH LARGE (1 1 000+) OUTFLOWSS OF HNWIS IN 2017

| City (alphabetical) | Country |

|---|---|

| Istanbul | Turkey |

| Jakarta | Indonesia |

| Lagos | Nigeria |

| London | UK |

| Moscow | Russia |

| Paris | France |

| Sao Paulo | Brazil |

Source: NWW (2018)

Table 6 TOP 10 COUNTRIES FOR HNWIS, MULTI-MILLIONAIRES, AND BILLIONAIRES (2017)

| Rank | HNWIS | Multi-millionaires | Billionaires | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | No. of residents | Country | No. of residents | Country | No. of residents | |

| 1 | United States | 5 047 400 | United States | 221 580 | United States | 737 |

| 2 | Japan | 1 340 900 | China | 40 930 | China | 249 |

| 3 | China | 877 700 | United Kingdom | 26 130 | India | 119 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 826 900 | Japan | 25 470 | United Kingdom | 103 |

| 5 | Germany | 813 300 | Germany | 25 070 | Germany | 82 |

| 6 | Switzerland | 406 900 | Switzerland | 21 400 | Russian Federation | 79 |

| 7 | Australia | 376 600 | India | 20 730 | Hong Kong (sar), China | 56 |

| 8 | Canada | 372 700 | Canada | 12 510 | Canada | 44 |

| 9 | India | 330 400 | Australia | 12 340 | France | 41 |

| 10 | France | 305 200 | Hong Kong (sar), China | 11 200 | Australia | 36 |

Source: NWW (2018).

Table 7 TOP 10 CITIES FOR HNWIS, MULTI-MILLIONARIES, AND BILLIONAIRES (2017)

| Rank | HNWIS | Multi-millionaires | Billionaires | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | No. of residents | City | No. of residents | City | No. of residents | |

| 1 | New York | 393 500 | New York | 17 610 | New York | 68 |

| 2 | London | 353 600 | London | 11 950 | Hong Kong | 56 |

| 3 | Tokyo | 321 800 | Hong Kong | 11 200 | Beijing | 52 |

| 4 | Hong Kong | 250 700 | San Francisco Bay Area* | 10 250 | Shanghai | 52 |

| 5 | Singapore | 239 000 | Los Angeles** | 8 900 | London | 47 |

| 6 | San Francisco Bay Area* | 220 000 | Tokyo | 7 770 | Moscow | 45 |

| 7 | Los Angeles** | 199 300 | Singapore | 7 700 | San Francisco Bay Area | 41 |

| 8 | Chicago | 150 200 | Beijing | 7 110 | Los Angeles** | 35 |

| 9 | Beijing | 149 000 | Chicago | 6 950 | Seoul | 28 |

| 10 | Shanghai | 145 800 | Shanghai | 6 940 | Mumbai | 28 |

* The San Francisco Bay Area includes San Francisco, San Jose, Oakland, Palo Alto, Los Altos, Redwood City, Moraga, San Mateo, and Mountain View.

** Los Angeles includes Los Angeles, Beverley Hills, and Malibu.

Source: NWW (2018)

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article demonstrates a very high concentration of wealth among small elites and identifies the various incentives for the wealthy to leave their home countries and reside in locations where their assets are better protected and the quality of life is good. The international mobility of people (global migration) is showing signs of increasing divides, driven, in part, by the existence of more favorable migration regimes catering to the wealthy compared with the immigration rules for the non-wealthy. So-called investment migration regimes offer visas and citizenship rights in exchange for capital contributions to host country government funds and investments in real estate and the local banking system. This contrasts with cumbersome, bureaucratic migration systems oriented to deter entrance and permanence for working migrants often coming from the periphery of the world economy. Mass migration can be politically contentious due to possible adverse effects on wages, pressures on publicly provided education, housing and health services, and different cultural backgrounds. In the case of the migration of the wealthy, most of these considerations are not particularly relevant. The number of wealthy migrants is small compared with the migration of working people; the wealthy often do not compete for jobs with nationals (although they may in the case of senior managers and highly paid professionals). Moreover, the wealthy bring fresh funds and market contacts. At the same time, certain features associated with the arrival of the wealthy can be disruptive: their investments in residential or commercial property in receiving countries pushes up property prices there, crowding-out nationals who cannot afford to acquire or rent housing that has become expensive after foreigners’ purchases. In addition, the potentially corruptive effect associated with inflows of foreign money on the local political system should not be discarded a priori.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)