Introduction

Milton Caniff was born in Hillsboro, Ohio, in 1907 and died in New York City in 1988. He is recognized as one of the most influential creators in the development of sequential narrative. He always worked on comic strips that appeared in U.S. newspapers, and, therefore, he considered himself a cartoonist, a term that defines an author of this type of comic. At the beginning of Caniff’s career, the term “cartoonist” referred to an artist who illustrated the graphical sections of magazines and newspapers. Even if the comic strips, especially the adventure comic strips for which Caniff would become famous, differ from these initial illustrations, authors who worked exclusively for newspapers as Caniff did preferred the term “cartoonist” because publishing in this medium determined their work enormously, due to the fixed format of the strips and the Sunday pages. Additionally, in Caniff’s case, it would have some implications for Americanism because he considered comic strips and jazz the only truly U.S. American artistic expressions (Harvey, 2007: 327). Although the term “cartoonist” has been extended to other comic artists such as those working in comic books, or even to those in of animation, in Caniff’s years, it was very linked to artists working for the press.

Caniff began working in 1930 with a permanent job at the Columbus Dispatch, a local Columbus, Ohio newspaper. Because he had difficulties finding work in his home state, he moved to New York in 1932 to take a job in the Entertainment Service of the Associated Press syndicate. There, he took over the series Mister Gilfeather from cartoonist Al Capp. He would draw that series until spring 1933, when he started to work on The Gay Thirties, a single panel series, which he would produce until he left the Associated Press in autumn 1934. While working on The Gay Thirties, Caniff had also began an adventure series called Dickie Dare about a young man who dreams of participating in the adventures of characters like Robin Hood, Robinson Crusoe, or King Arthur. Beginning in spring 1934, Dickie Dare would no longer dream his adventures: they would happen outside the dream world. At that time, Dickie began traveling with his mentor, writer “Dynamite Dan” Flynn, participating in different stories around the world. Caniff worked on both series until the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate in autumn 1934 offered him a job. This syndicate, directed by Captain Joseph M. Patterson, hired him to create a new series called Terry and the Pirates. Caniff continued to work on it until the end of 1946. That year he stopped narrating the adventures of Terry and his pals to create Steve Canyon, a new series that debuted in January 1947. The reason for this change was the author’s need to control his work. Because Terry was a syndicate assignment, Caniff did not own the rights to his work. This not only prevented him from having creative control over the series but also kept him from benefitting from the products derived from the series’ success, such as radio serials or film adaptations, which, in Caniff’s opinion, did not meet the artistic level of the original work. This lack of control led him to create a new series to which he had all the rights, allowing him to control all the elements derived from it. Caniff worked on this new series, Steve Canyon, until his death in 1988, rejecting offers to work in other comic-related media, such as the adult magazines of the 1970s, because he considered himself not a comic artist but a cartoonist.

As Lawrence E. Mintz states (1979: 664), “Caniff uses the new realism in his early and continuing interest in drama,” and he was very aware that in his time, “every sort of ideology was banging the eyes of the nation” (Caniff, 1946: 489). He identified this realism with his own beliefs. From the beginning, his philosophy was very close to what he understood as U.S. American roots, an ideology that would later be dubbed by several authors as Americanism. Americanism is a complex ideology that Kazin and McCartin defined as “an articulation of the nation’s rightful place in the world, a set of traditions, a political language, and a cultural style imbued with political meaning” (2006: 13). According to David Gelernter, Americanism is the fourth great Western religion and brings together a set of values in which a substantial majority of the U.S. American people believe, regardless of their religious ideas (2007: 2-4). As Richard Hofstadter states, “It has been our fate not to have ideologies but to be one” (Hofstadter and Ver Steeg, eds., 1969: 42). In this way, “those who accept Americanism do so mainly because we recognize its principle as true” (Gelernter, 2007: 6). These values are based on the ideals of liberty, equality, democracy, and particularly on the capacity of the U.S. American people to extend those ideals to other places in the world, more specifically to those places in which these ideals have been violated. “One should also add the remarkable self-confidence of most [U.S. ] Americans [… ] that they live in a nation blessed by God that has a right, even a duty, to help other nations become more like the United States” (Kazin and McCartin, 2006: 10).

This article analyzes the ways in which Americanism and its values appear in Milton Caniff’s work. More specifically, it studies the series he authored, Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. I analyze the values of Americanism from a dual point of view. One point of view is my own, in which I analyze the content of his work and the ways in which it expresses the ideals of Americanism. The other is the reader’s point of view and the ways in which he/she receives these ideals as well as their repercussions. Based on this idea, I present some excerpts from the letters Caniff received from his audience.1 These documents have been obtained from the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, where all Caniff’s documents are preserved, including his correspondence, which he donated before his death. This will explain how he followed the tradition of “filmmakers and wartime propagandists like Frank Capra [who] depicted [U.S. ] America as one big, friendly house for ordinary people of all religions and races,” (Kazin and McCartin, 2006: 6), or, as Jun Furuya explains, how “this popular culture [… ] showed a different aspect of Americanism” (2006: 192).

The Terry and the Pirates Years

As mentioned above, Terry and the Pirates was created in 1934 when The New York Daily News hired Caniff to create a new adventure series for the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate. The idea for the series came from the syndicate’s director, Captain Joseph M. Patterson, who wanted an adventure story set in the mysterious East that included all the elements that would make it attractive to a wide audience: a young character searching for adventures, a handsome hero for the action scenes in which physical prowess was important, a character for comical relief, and beautiful, sensual women. Finally, the series would include the pirates as villains who could serve as the trigger for the story’s main leitmotiv: adventure. Making use of all these elements, the series’ first daily strip was published October 22, 1934, while the first Sunday page appeared on December 9 of the same year.

Terry and the Pirates starts with the search for treasure in China, defined by Captain Patterson as the last outpost for adventure (Harvey, 2007: 194). The term “outpost” is the first proof of Americanism in Caniff’s work and reflects the nostalgia of Middle America for the frontier, what had been the basis for the creation of the American Dream, which, in a certain way, had been destroyed by urban society. Terry and the Pirates was created during the Great Depression, when urban society was in crisis because it was considered the origin of that economic collapse. Under these circumstances, nostalgia for the frontier intensified. A feature of the U.S. American people had been their migration in search of frontiers to conquer and outposts to establish. Even today, U.S. Americans have less difficulty than other societies, such as Europeans, in leaving their homes when necessary and moving to places with better conditions, even if this is within U.S. borders. The Great Depression exacerbated this need to travel. It is interesting to remember that The Grapes of Wrath, perhaps the period’s most representative novel, is the chronicle of forced migration in the search of better working and economic conditions. Terry and the Pirates reflects the need during that period to seek out new territories, albeit with a more playful, adventurous approach.

This idea of the “Orient” as outpost not only links to U.S. American nostalgia for the frontier but also to the myth of the Orient, a recurring topic since Antiquity, which has inspired many stories involving this myth of the frontier. As Edward Said famously wrote in his book Orientalism, published in 1978, U.S. Americans became the heirs to those French-Anglo (and other European colonialist) cultural perspectives that had been forming since the beginning of East-West contact (Said, 1990: 338). In fact, when Terry and the Pirates started, the series was an adventure story with no other virtues, reflecting the legacy of Orientalism Said mentions. However, little by little, its realism increased and it turned into a chronicle of China and its relationship with United States in those years. Then, when China was invaded by Japan in 1937, war was introduced into the series. Caniff turned into a chronicler of the conflict to the extent that, as Cat Yronwode explains, for many U.S. Americans, Terry and the Pirates and not Pearl Harbor showed the way to World War II (1982: 217). Caniff would play this role for the entire conflict. In first, he addressed the resistance of the Chinese people and then turned the Dragon Lady character, until that point a pirate queen, into the leader of a crusade against the invaders. Just as news arrived describing the fall of Chinese cities after the 1938 and 1939 bombings, Caniff presented the consequences of the attacks in the series. It should be noted, however, that Caniff does not mention the Japanese when he refers to the invaders due to the United States’ neutrality. However, their facial features as well as the Rising Sun flag left no room for doubt about their identity.

As mentioned above, one of the most important elements in this chronicle of the Sino-Japanese war is Dragon Lady and her transformation from pirate queen to resistance leader. One of the factors that allowed the Japanese to quickly take control was the division among the Chinese into government factions spread throughout the country, making it rather difficult for Generalissimo Chiang to govern a divided nation. The Japanese army took advantage of this disunity to take control of the governments of each region, placing them under Chinese warlords, who had no problem collaborating with the invaders in exchange for power. The story narrated in Terry and the Pirates from July 13 to November 5, 1939, depicted the people’s fight, led by Dragon Lady, against the collaborationists. As Edgar Snow explained, Chinese Communists were the main force fighting the invaders (1968: 6). As a result, Snow considers the expulsion of the Japanese invaders to be fundamental in the triumph of communism in China. Again, Caniff does not identify the resistance with the Communist movement, but Dragon Lady’s behavior identifies her with some of the Chinese resistance leaders Snow described like, for instance, Mao Tse Tung and Huang Ha. Caniff developed in fiction what Henry R. Luce had created in the real world as he “was the publisher who had put Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek on the cover of Time, together or separately, a whopping eleven times; in 1939 they were ‘Man and Wife of the Year’” (Whitfield, 2006: 102). However, although there were some female leaders in China, none of them had Dragon Lady’s power. This kind of female Communist leader could be found in another of the conflicts of that period, the Spanish Civil War in the figure of La Pasionaria. The fact that Snow himself says that the “Japanese might succeed in turning the Nanking government into a real Franco regime of the East” (1968: 143) shows the parallels established at that time between the Chinese Communist resistance, led by Dragon Lady in the fiction, and the Spanish Communist resistance, one of whose prominent figures was a woman.

Both before and after the United States entered the war, unofficial support existed for the Chinese resistance, including campaigns by some of members of show business and the press in favor of the movement. Edgar Snow’s work, followed by Caniff as the documents in his archives prove, is an ode to the Chinese Communist resistance. Snow developed ties of friendship and collaboration with some resistance leaders in the same way that Pat Ryan and Terry Lee collaborate with Dragon Lady in Terry and the Pirates. Caniff publicly takes a stand by having the two U.S. Americans collaborate with the Chinese resistance at a time when the U.S. government had not taken any official position regarding the conflict. Caniff’s position was aligned with the progressives in U.S. society. They favored an end to U.S. neutrality in the case of the Japanese invasion of China and of the rise of Francoism in Spain. For example, an editorial published by Henry R. Luce in the February 17, 1941 issue of Life insisted that the United States would soon be fighting in World War II, inspired by democratic ideals and the promise of prosperity (Whitfield, 2006: 90). This position reflects Gelernter’s statement about the definition of Americanism with respect to the U.S. attitude toward war: “Many assume nowadays that there are two ways to look at war: pro or con, for or against, warmonger or pacifist. [U.S. ] Americans have traditionally rejected this naïve dichotomy and insisted on a third alternative that grows straight out of the Hebrew Bible. [… ] This third view is chivalry” (2007: 24).

This chivalry, defined as a “willingness to intervene on the side of right,” (Gelernter, 2007: 68), is a legacy of the ideas gathered by Ramón Llull in the thirteenth century, when he wrote that an aspirant to chivalry must “protect the rich” and “be ready to go out from his castle to defend the ways and to pursue robbers and malefactors” (2006: 36). It also stems from Leon Gautier’s code espoused in his 1833 work Le Chevalerie, in which, under the influence of romanticism, the author made a study of chivalry that influenced its perception in the years after its publication (1960). Therefore, Caniff believed that after the Japanese invasion, the mission of the U.S. American people was to intervene and stop the outrages of this invasion in China. As Enrico Fornaroli stated, “As Robert Jordan will offer his own sacrifice to the Spanish Republicans, Terry [… ], on the opposite end of the hemisphere, will be on the side of the Chinese resistance” (1988: 117-118). This attitude and Caniff’s capacity to reflect a military conflict had little impact on the news of that period, as most people were more worried about local economic changes. However, Caniff’s position was strengthened when the Office of Emergency Management appointed him as a consultant. The letter came directly from the Executive Office of the President on June 14, 1941 (some months before Pearl Harbor), signed by Sydney Sherwood, director of the Division of Central Administrative Services. It stated, “Dear Mr. Caniff: At the request of Mr. Robert W. Horton, Director of the Office of Information, Office for Emergency Management, you are appointed as Consultant without compensation for an indefinite period, effective June 16, 1941. […] We appreciate your patriotic cooperation in this very important aspect of the defense program.”

Caniff, who could not join the U.S. army for health reasons, considered himself part of the military and was rewarded for his chivalry as a part of the U.S. American people supporting the Chinese struggle. Then, after Pearl Harbor, he could depict the Japanese army as the enemy without any subterfuge. During World War II, the series served as a chronicle defending the principles of Americanism and U.S. intervention in the Pacific War against the Axis forces and in defense of the oppressed Chinese people. In his fictional stories, Caniff includes real testimonies sent by soldiers and nurses because he knew that his description of the war’s events would reach more than 30 million people who were fans of the series at that time (Caniff, 1946: 491). Thus, hundreds of letters in Caniff’s correspondence are similar to that of Grace Kidder, a girl from New Jersey, who wrote on March 7, 1945 to say, “Reading about Terry and the boys, I have an idea about what my own brother could be doing.” Caniff’s work was recognized by institutions such as the Committee of the Hospital of the American Theatre Wing War Services, who thanked him for his devotion to hospitalized combatants, and the Naval Construction Battalion, introduced to the public by the events narrated in the strip.

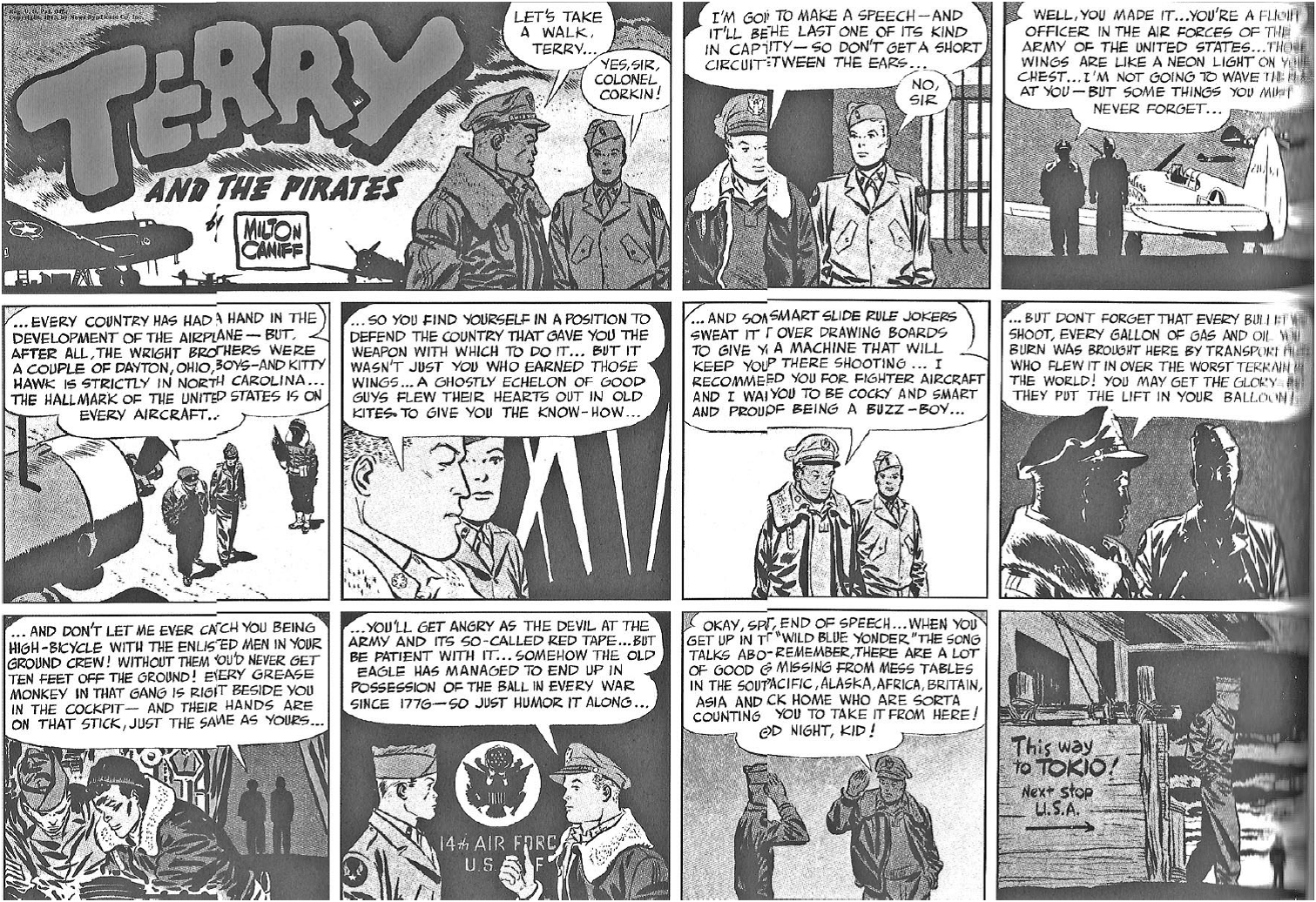

The series is full of events to elevate troop morale, and those are examples of the values of Americanism behind the U.S. army mission in China. Then, on February 22, 1942, Caniff used George Washington’s birthday to dedicate the whole Sunday page to a speech by Pat Ryan summarizing the fight for freedom throughout the history of the U.S. American people (Figure 1). This speech was given to the rest of the strip’s characters, but Caniff’s intention was to address it to the 20 million U.S. Americans who constituted Terry’s circulation in 1941. He had the same intention when Colonel Flip Corkin reminded Terry of his duties and responsibilities in the war after Terry became a pilot in one of the most famous Sunday pages of the series, published October 17, 1943 (Figure 2). Pages such as these had a strong impact on the readers, who thanked Caniff for his role as defender of the values of Americanism. Thus, Mrs. Chas C. Smith from Philadelphia emphasizes in August 1942 “the overwhelming, true American spirit. I don’t have gas in my car. Without petrol this winter, I will be cold. A new dress is out of the picture, I just bought a war bond, but who cares while the real Terry and the Pirates can still carry on.” Or David Kagan from Mississippi who wrote, “A Medal of Honor should be given for doing something that no other cartoonist dares, that is to say, join reality and fiction and give all [U.S. ] Americans the lesson that we need.” This Sunday page not only had an impact on readers but also on the army. For example, Lieutenant Commander Dred G. Hirsch of naval aviation wrote, “I heard many good flight talks and speeches addressed to the newly designated pilots by some of the most important Navy bosses, but none of them hit the jackpot like you did on Sunday.” Similarly, General Arnold still remembered this episode in February 1944, writing that the “AAF has reasons to thank you for your sympathetic interpretation of its intentions and its achievements.” The page’s impact was important enough to be read by Congressman Carl Hinshaw in the House of Representatives the day after its publication and included in the Congressional Record (Figure 3).

In its tribute to American values and their representation in the Pacific War, it is important to note that starting in 1944, the strip published closest to Christmas Day was always a tribute to the war casualties, reflecting another characteristic of Americanism: “Americans [… ] respected the common soldier” (Gelernter, 2007: 60). In the end, as Kazin and McCartin argue, “The massive Grand Army of the Republic created the ritual of Memorial Day to associate love of country with selfless loyalty in battle” (2006: 4). This tribute also touched the readers, as reflected in a letter from a woman in Chicago reacting to the first Christmas strip after the war, “Thank you very much! For what? For not letting Mr. & Mrs. America forget at Christmas time that even though we here in the U.S. are celebrating Christ’s birth at ‘peace’ for the first time in five years, there are still some of our fathers, husbands, brothers, etc. giving their lives in foreign countries.” However, Americanism does not require following the mandate of the U.S. government. As Jürgen Gebhardt has argued, Americanism is not strictly blind patriotism, but a broader moral conviction (1993: 57). In this way, Caniff also criticizes the presence of U.S. citizens and the role of their government in foreign countries. Once the war ended, a high commander of the U.S. army stated in the March 12, 1946 strip, “I sometimes think the Chinese would be happy if we would take our victory and get on back to America” (Caniff, 2009: 224). The defense of the values of Americanism does not preclude the analysis of real events, which is one of the strong points of Terry and the Pirates during Milton Caniff’s tenure with the series.

The Race Question

David Gelernter mentions Abraham Lincoln as one of the fathers of Americanism. The basis for this claim is Lincoln’s defense of U.S. American values (liberty, equality, and democracy) in his fight for the abolition of slavery. Therefore, when studying an author’s Americanism, one of the most important aspects to consider is the way he/she addresses what Carey McWilliams called the “race problem” or the “race question” (1946: 89). In his work on Terry and the Pirates, set during World War II in China, Caniff’s Americanism is shown in the way he describes Asian characters. Several important Asian characters appeared in the 12 years that Caniff wrote and illustrated the series, but the one that has remained in the popular imagination is Lai Choi San, best known as Dragon Lady. At the beginning of the series, Dragon Lady was a voluptuous Chinese woman pirate, who very soon became one of the most important rivals for Terry and Pat from the beginning of the series, sharing this antagonism with a sexual tension, first with Pat and then with Terry as he grew older. This sexual tension would become one of the most interesting things in the series.

In her book on Orientalism and Asian-American identity, Shang-Mei Ma identifies Dragon Lady with what she defines as the Fu Manchu stereotype (2000: 9). The pertinence of the Dragon Lady to this stereotype in Caniff’s work might be true at the beginning of the series. However, as the series evolved, and following this idea of Americanism, Caniff became worried about his depiction of other races. For this reason, the series quickly moves away from this stereotype and transforms Dragon Lady into a three-dimensional character. Dragon Lady changes very swiftly from an Oriental menace into a femme fatale. She develops the features of the femme fatale, whose presence Nuria Bou defined in American film noir of that period as the heiress of the Pandora myth (2006: 20). One of the arguments that Ma uses to prove Dragon Lady’s inferiority as an Asian character is that she becomes captivated by Pat Ryan’s charm. This claim is disputable. A mutual attraction exists between both characters, but Dragon Lady does not allow it to interfere with her objectives. However, the sexual tension between Pat and Dragon Lady is an expression in the comic strip of the confrontation between the diurnal and the nocturnal regimes that Bou argues, following Gilbert Durant, are present in the classic cinema and also in Caniff’s work, which often intersects with the cinema of his time. There is no racial component in the relationship between Pat and Dragon Lady. In fact, the strip could be accused of making the character appear more Occidental. Dragon Lady was inspired by Joan Crawford, and Pat behaves with her just as he does with the other important femme fatale in the series, Burma, whose racial features are typically Aryan, but whose relationship with Pat does not differ substantially. It is important to consider that Caniff often received letters asking for drawings of Burma or Dragon Lady, usually in erotic poses. Almost the same number of letters can be found for both characters. Therefore, no evidence exists that the audience perceived a difference in the treatment of the race. A letter from one of Caniff’s readers can be mentioned as an example of the hundreds that he received praising Burma or Dragon Lady’s qualities: “Dear Dragon Lady, I think you are the most wonderful woman alive, and one of the bravest. If all women were as brave, as courageous, as beautiful, and had as much real nerve and daring as you have, all of us would enjoy life better” (from Jourdanton, Texas, June 1940).

Dragon Lady even became an inspiration for both Harvard and Yale. Yale requested a picture of Dragon Lady for their junior prom in 1939, and a jealous Harvard asked for one for their boathouse 13 days before the Yale-Harvard race. The popularity of this creation was mentioned in Time and Life, and some readers responded to it:

After reading in the magazine, Life, of your gift to the Harvard crew, I began to realize the power of the Dragon Lady. I can readily understand how young men would row their “hearts” out with such inspiration. I feel rather certain that the stimulus that a picture of the Dragon Lady would produce might change a mediocre man into a regular Cross Country demon.

Certain famous people also fell under Dragon Lady’s charm, such as Orson Welles, Joseph Cotton, and John Steinbeck, who sent letters to Caniff, preserved in his archive, praising the character’s qualities and even asking him for portraits of her.

We can see that the readers did not perceive any racial stereotype. More important than the description of Dragon Lady and its stereotypical depiction of an Asian villain is her evolution from a Chinese pirate to the leader of the Chinese resistance when the Japanese invade, as mentioned in the previous section. This is another example of Americanism. Caniff made the U.S. American characters in the strip, Pat and Terry, join the Dragon Lady in her fight against the invaders. In this historic moment, although the United States had not joined the conflict, one part of U.S. society, following the ideals of Americanism, wanted to fight for freedom in countries like China and Spain. Caniff supported this viewpoint by having his U.S. American characters fight for liberty in China. Dragon Lady was no longer -nor was she ever- an Asian stereotype, but an example of the collaboration between China and the United States even before this collaboration happened historically.

To conclude this topic of stereotypes, the beautiful interracial love story between Terry and Hu Shee must be mentioned. It could imply the subjugation of the Asian character by the U.S. American. Caniff even makes use of this character to express his Americanism when Terry meets her again years later. The United States had entered the war, and she reproaches him for the U.S. army’s delay in providing support to the oppressed Chinese people. On February 1, 1945, Terry and Hu Shee meet again, and she is now part of the Chinese resistance. Terry says “The last time we saw you was before the war, Hu Shee.” And she answers, “Before your war, Terry” (Caniff, 2009: 51). This answer, even though short, is one of this fictional story’s sharpest criticisms in addressing the United States’ lack of intervention in the Sino-Japanese conflict before Pearl Harbor, when China was completely engulfed in that fight.

It is not this section’s intent to dismantle Ma’s thesis, but to analyze how the treatment of race is an important part of U.S. history and, therefore, of Americanism. As Carey McWilliams affirms, race was an important question in examining U.S.participation in the war:

Great changes have taken place in race relations in [U.S. ] America since the beginning of the war. By accelerating processes long at work in our democracy, the war has quickened the pace of cultural change. It has telescoped pre-existing tendencies, brought to light long-dormant issues, and sharpened numerous contradictions. By focusing public attention upon “the race problem” in all its ramifications, it has aroused a new national interest in racial minorities and stirred to life a new national conscience toward these groups. (1946: 89)

Caniff was concerned about the depiction of different cultures, as can be deduced from his response to the letter of a woman from Welton asking whether he was thinking of introducing a black character into the strip. Caniff doubts whether he can or should do this:

If the Negro or Negroes are made the musical comedy low comedian sort, the justified protests from Negroes are bound to follow. If he’s shown as a perfect normal individual, the inevitable protests and cancellations will come from the southern newspapers carrying the strip. If both types are included, it means doing a sequence devoted almost exclusively to the activities of Negroes, which is almost certain to bring protests from southern papers.

Thus, Caniff was very cautious when depicting characters of other races, which had been impossible to avoid in the case of the Asians given the strip’s setting. Racial discrimination is a fundamental part of U.S. history. Caniff, as a U.S. American, often falls victim to mistakes in this regard, but his Americanism causes him to try to find a position of equality. He was aware of the Japanese propaganda arguing that World War II was a racial war, indicated in these lines from a Japanese broadcast of March 15, 1942: “Democracy as preached by Anglo-Americans may be an ideal and a noble system of life, but democracy as practiced by Anglo-Americans is stained with the bloody guilt of racial persecution and exploitation” (McWilliams, 1946: 90). Even before the war, Caniff was aware of this, and he tried to show the humanity of all his characters, as the December 1, 1940 Sunday page demonstrates when Japanese soldiers took care of a wounded Terry. The humanity of the race was shown without considering their racial origin.

However, Ma’s analysis is also a historical reflection of U.S. society’s concern about racial conflicts, which is still important today. Every time a black or Asian character was introduced into a comic series, it resulted in some sort of controversy among the readers. When Black Panther appeared in Avengers issue 72 in January 1970 and hid the fact that he is black because he wants to be judged as a man, Phillip Mallory Jones, a black reader, sent the following comment to the comic book’s letters section: “That’s very white of you. This implies that this champion of justice, etc., could not be considered a man if it were known that he was black, that in fact, only if there is a chance that he is white can he be judged as a man. This is to say nothing of the aberration of revolutionary nationalist or cultural nationalist (if there is a distinction) doctrine.”

Much more recently, in 2006, in the series The Walking Dead, the governor beats and rapes Michonne, a black character, with extreme violence. Here is the letter sent by Sundjata Abubakari and published in the letter section of issue 32 of the series:

As a man of African descent, I was quite disturbed and appalled by the image of a strong, powerful black woman stripped of her power and humanity by being raped and brutally beaten by a white man not once but twice in the same issue.…I understand the idea of dramatic effect in storytelling, but goddamn it, did Michonne have to be tied up spread eagle, raped, and tortured? Did a strong black woman have to be broken down to the lowest of the low? Is it a case of art imitating life in the sense that if black people are too strong, they not only have to be stopped but destroyed? Would you have put any of the white female characters in the book through the same ordeal? I don’t think you would have. You never see strong white female characters in comics being dehumanized like that. I guarantee that Michonne’s fate will not be shared by Supergirl, Power Girl, and certainly not Wonder Woman... I’ll spare you a lengthy diatribe about how the rape of African women by white men was part of the dehumanization process during slavery, but I will say that I know several African American readers of The Walking Dead, and they too have expressed their disgust at the portrayal of a black woman being raped by a white man. Some of them told me that they’re not going to read the book anymore. The black female readers that I know have especially expressed their disgust.... I don’t know if I can read it anymore after this.

Not only black characters spark controversy in readers; those of Asian origin do also. Here is a reaction from Bill Wu to the character of The Mandarin published in the letter sections of Invincible Iron Man issue 72 in January 1975: “The name ‘Mandarin’ with its cultural connotations should be replaced. It’s bad enough that you flirt with Yellow Peril racism at all; the least you can do is tone it down a little.”

Race and the way it is depicted is ultimately another feature of Americanism.

The Steve Canyon Years

At the end of 1946, Caniff abandoned Terry and the Pirates because he was tired of not having the rights to the creative control of his work. He immediately started his new series, Steve Canyon, first published January 13, 1947, which he would work on until right before his death in April 1988. As Umberto Eco notes, E can be considered the mature version of Terry as he starts by trying to reinsert himself into society after the war (2010: 164). However, he would quickly become a reflection of the United States and would return immediately to active service. According to Gelernter, if Americanism led Harry Truman to drive the United States into the Cold War (2007: 18), then Steve Canyon’s story is the reflection of this U.S. presence in all the conflicts around the world. Steve Canyon thus assumed the role of world guardian, and he would be wherever U.S. interests were threatened. Canyon became a tireless fighter against Communism throughout the world. In this ideological war, Caniff defends U.S. American values above everything else through his character. Even in an illegal war like Vietnam, the presence of Steve Canyon cannot be avoided as a hero whose roots are in the mythical constructions of the U.S. American people.

Caniff received strong criticism for his conservatism in this work. In Spain, this caused Carlos Giménez to refuse to give a prize to the author at the Gijon comic convention because he considered Caniff the most reactionary cartoonist in the history of the medium (as covered in El País on July 24, 1979). Similarly, in his analysis of Caniff as a U.S. American, Claudio Bertieri states,

The side that takes to Caniff is not difficult to guess, given the long list of awards he has received in 20 years. They have been bestowed by the establishment for his comprehensive Americanism, for the values that his two greatest characters have been the most convincing advocates of and propagandists for....He believes in a certain type of society, in a community that does not have the right to relax “during peacetime” because the enemy is always at the gates, in a youth that should be filled with pride when put in uniform, in the veterans who meet every year to celebrate “flag day,” in war widows “who would not change places with any other woman in the world.” His message is for Order, Strength, Patriotism. (1969: 16)

This idea of conservatism, which at the same time should not invalidate the artistic value of his work, truly reflects the vision that many people outside the United States have of the evolution of U.S. society. The U.S. society that had significantly supported the Communist resistance movements in China and Spain becomes the leader in the fight against Communism. Caniff, an adept follower of Roosevelt during World War II, became more aligned during the Cold War with the Republican Party. As an example of this, he maintained correspondence during these years with some Republican presidents like Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan. These letters are conserved in Caniff’s archive. Again, this is a reflection of the evolution of Americanism through history. Kazin and McCartin said that the hunt for “un-American” activities meant that “by the late 1960s, Americanism had become virtually the exclusive property of the cultural right” (2006: 6). The change in this tendency was the Vietnam War. “The politics of the Vietnam War played a critical role in this change. In a decisive break with tradition, leading activists in the protest movements of the era took issue not just with government but with the ideals from which those policies were supposedly drawn” (6). The conservative right claimed Americanism as their cause, considering the opposite movement to be anti-Americanism. However, in the end, “Americanism and anti-Americanism are names for two sides of one coin. This paradox has something to do with a feeling some people had during the war in Vietnam and, later, the war in Iraq, which is that it is possible to be a patriot and a dissident at the same time” (Menand, 2006: 205).

Caniff could not escape this paradox. Following the conservative version of Americanism of that period, Caniff enrolled Steve Canyon to fight in Vietnam. However, his readers’ response made him re-think this. “The whole Vietnam thing has brought out the attitudes of the younger people. An abhorrence of the whole thing which everybody feels, and the misery of supporting a conflict in an area which they not only don’t understand but can’t pronounce. The World War II point of view was quite different” (Harvey, 2007: 82). However, the author was loyal to his ideals, and despite many newspapers cancelling the series because they thought that it supported a shameful war, he kept his character in the war because, “I was simply showing a military person in a military situation doing a military job. The reasons why we were there had nothing to do with it. The fact was we were there and I didn’t think we should turn our backs on the situation” (Harvey, 2007: 179).

Conclusions

Throughout his career, Milton Caniff was one of the most important authors of adventure comic strips. However, one thing that distinguishes him from his colleagues is that his work can be read as a chronicle of U.S. war efforts during the twentieth century in the period of the World War II and the Cold War. Caniff’s position during all these conflicts was always on the side of the official U.S. position at any moment in history. Therefore, his work evolves from a more progressive approach to a more conservative one in the same way that society itself did. Several authors have analyzed this evolution of U.S. society, resulting in the concept of Americanism as the belief of an important part of U.S. society in the moral superiority of their values and the necessity of propagating them throughout the world. The concept of chivalry is very important here and explains some of the reasons for U.S. military intervention in different parts of the world. Caniff was not able to fight in any war, as his father and his grandfather had. Health issues prevented him. However, even before World War II, he received an honorary appointment as a consultant for his work as a chronicler of the war in the Pacific and the conflict between the Chinese and the Japanese. He took this appointment very seriously, and his work from that point forward is an example of Americanism. His pages often reflected the U.S. American values of the corresponding historical moment, and his characters were examples of chivalry, from Terry and Pat Ryan fighting on the side of the Chinese against the Japanese to Steve Canyon travelling around the world in his fight against Communism during the Cold War.

Countless examples in comic strips and comic books show a similar position to Caniff’s during the years of World War II. The most famous currently are Captain America, created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1941, whose first cover had an image of the U.S. hero beating Hitler. Most U.S. superheroes were fighting the Axis in their stories during those years, in part because most of their creators were Jews (Fingeroth, 2007). Joseph Goebbels’ statement on the Jewish character of Superman is well-known (Fingeroth, 2007: 23). In the comic strips, the situation was no different, and most of the series published in newspapers were involved in the conflict in one way or another (Caniff, 1946: 491). Two things distinguish Caniff’s work from that of other creators: first, his U.S. American characters were involved in the war before any other comic strip characters, supporting the Chinese resistance against the Japanese invasion at a time when the United States was neutral. The second distinguishing feature is that none of the authors whose characters and series supported U.S. efforts during World War II kept their stories as close to the country’s military values and to the values of Americanism for as long Caniff did. These values were the center of his stories from the beginning of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937 until his last stories in Steve Canyon, which coincided with his death in 1988. No other career in U.S. comics spanned as many years with these values at its core.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)