Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Norteamérica

versión On-line ISSN 2448-7228versión impresa ISSN 1870-3550

Norteamérica vol.5 no.1 Ciudad de México ene./jun. 2010

Contribución especial

The State of Democracy in Mexico*

Gustavo Ernesto Emmerich et alii**

** gustavoernestoemmerich@yahoo.com.

Received: 01/02/2010

Accepted: 21/05/2010

Abstract

This report is an abridged version of a democratic audit of Mexico conducted by an independent group of Mexican scholars. Its results seem relevant at a time when the country is discussing how to enhance its very new democracy. Section A summarizes the conceptual and methodological approach adopted. Section B describes the Mexican context –mainly for the sake of foreign readers. Section C presents the main research findings. Section D contains the conclusions and some proposals. The foremost conclusion is that while Mexico has indeed made significant democratic advances, it still faces many challenges to improve the quality of its democracy.

Key words: Mexico, democracy, governance, politics, democratic conditions.

Resumen

Este artículo es una versión abreviada del examen que realizó un grupo independiente de académicos mexicanos. Los resultados parecen relevantes en un momento cuando el país está discutiendo cómo mejorar su reciente democracia. La sección A resume el enfoque metodológico y conceptual usado, la sección B describe el contexto mexicano, en particular para el beneficio de los lectores extranjeros. La sección C presenta los principales hallazgos de la investigación y la sección D contiene la conclusión y algunas propuestas. La conclusión más importante es que mientras México ha tenido un desarrollo democrático significativo, todavía enfrenta muchos retos para mejorar la calidad de su democracia.

Palabras clave: México, democracia, gobernanza, política, condiciones democráticas.

A. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

There is no such thing as a perfect democracy. Democracy is not an all–or–nothing affair, but a continuum. Countries are more or less democratic, and often more democratic in some aspects, less in others. Within this framework, it is worthwhile asking: How democratic is our country and its government? Or, in the case of this study: To what extent is Mexico a democracy?

To answer these questions, the team conducting the audit followed a methodology developed by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance [IDEA], 2002a).1 This methodology puts forward two basic democratic principles: popular control over public decision–making and decision–makers; and equality among citizens in the exercise of that control.2 Insofar as these principles are embodied in governing arrangements, the latter can be considered democratic (IDEA, 2002b: 11). To implement these principles, a set of mediating values is instrumental. They are citizen participation, authorization, representativeness, accountability transparency responsiveness, and solidarity. It is from these values that the institutions of representative government derive their democratic character, and it is these values that can be used in turn to assess how democratically they work in practice. Based on these notions, IDEA proposes an assessment framework focusing on four dimensions: a) citizenship, law, and rights; b) representative and accountable government; c) civil society and popular participation; d) and democracy beyond the state.

From these dimensions, 14 thematic areas are derived, each defined in scope by an overarching search question. The questions are phrased in such a way that a more positive answer would indicate a better outcome from a democratic point of view. In other words, they all "point in the same direction" along the democratic continuum. As such, they also entail a judgment about what is better or worse in democratic terms. Ultimately the questions call for a summary answer ranging from "very much" (optimal, nearer to true democracy) to "very little" (minimal, barely democratic), including "much," "middling," and "little" as intermediate points. As an example, the first area, nationhood and citizenship, includes the search question: Is there agreement on a common citizenship without discrimination? The summary answer given in this case was "much" agreement.

To answer the questions, the methodology requires a qualitative analysis encompassing both fact–finding and the establishment of standards for each thematic area. Fact–finding focused on, first, evaluating the applicable Mexican legal statutes from a democratic perspective; second, assessing how effectively these statutes are implemented in practice; and third, pondering both positive and negative indicators (steps toward democracy and setbacks and shortcomings, respectively). The establishment of standards implied defining what "very much," "much," etc., mean in terms of democratic advancement in Mexico. To set up the standards, several benchmarks were used. A central one was the Mexican Constitution: it was useful to partially answer the search questions by taking into account the distance between practical reality and what the Constitution promises in terms of citizen rights. For quantifiable matters, longitudinal comparisons were used to evaluate if the issue showed signs of progress –or setbacks– by comparing data from 1990 to around 1995 to the most recent ones available. Additionally, in some cases international comparisons and references to international covenants were used to determine how well Mexico is doing with respect to other countries. Finally, to know the citizenry's state of mind, a secondary analysis of public opinion surveys was conducted in the many areas where they are available. However, the reader should be advised that ultimately the summary answers are no more than the research team's informed judgment, and therefore debatable (for further details, see Emmerich, 2009: 9–14).

The 14 thematic areas, together with their respective overarching search questions and summary answers, are listed in Section C. Regrettably, in this abridged version, it was not possible to provide their analysis in full, but only the main findings. The exposition will follow another set of about 100 specific questions, summarized in a footnote at the beginning of each thematic area.

B. THE NATIONAL CONTEXT

Evolution to Democracy

Democracy has been quite foreign to Mexico. In its almost two centuries of independence, the country has made at least six attempts at democracy (figure 1). The first five failed. The sixth is underway at present and is the subject of this report.

From 1929 to 2000, just one political party ruled Mexico: the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).3 Based initially on nationalistic and social justice principles, through time it veered to the center –sometimes even to the right– of the political spectrum. Though other parties were allowed to exist, the PRI maintained absolute political hegemony.

The National Action Party (PAN) became the main opposition party since its founding in 1939. It defines itself as devoted to "political humanism," that is, liberal values based on respect for the individual. Often labeled as center–right, it is close to Christian Democratic parties elsewhere in Latin America and Europe. It combines a liberal approach to economics with a conservative approach to moral and some social issues. Another significant opposition party was founded in 1989: the left–wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

Since 1988, PRI hegemony weakened. Social modernization induced political pluralism. Economic crisis eroded the PRI vote. The media opened up to independent and opposition voices. The opposition parties received public funding. New electoral laws, practices, and institutions were created to level the playing field. As a result, a process of transition to democracy sped up.

In 2000, Vicente Fox won the presidential election as the candidate of a coalition of the PAN and the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM). The PRI came in second and the PRD, third. The peaceful, uncontested election of an opposition candidate after seven decades of one–party rule was a turning point signaling that Mexico had attained electoral democracy.

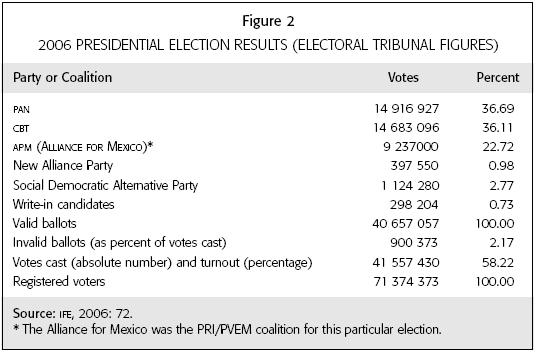

The 2006 elections were not so smooth. Felipe Calderón, of the governing PAN, was elected president with a tally of just 36.69 percent of valid votes (figure 2). Andrés Manuel López Obrador, from the left–wing Coalition for the Good of All (CBT, headed by the PRD), finished with 36.11 percent, and did not concede victory to Calderón. Three other candidates (including the PRI hopeful) got lower vote counts and did concede. Vitriolic campaigning and the virtual tie in the presidential race led to a prolonged post–electoral conflict, posing a test for Mexico's young democracy, particularly for its electoral institutions. Eventually, Calderón took office on December 1, 2006 with a country practically divided politically and socially with a significant portion of Mexicans who thought the elections had been rigged in his favor. For his part, López Obrador launched a "civil resistance movement," and symbolically proclaimed himself the "legitimate president."

Political and Electoral Institutions

Mexico is a presidential, federal republic made up of 31 states and a Federal District. It has three levels of government: federal or national; states and the Federal District; and municipal. This report focuses particularly on the federal government, but when necessary, takes into consideration the other two "sub–national" tiers of government.

The president, state governors, and the "head of government of the Federal District" (or Mexico City) are elected by plurality for six–year terms. They can never be reelected to the same positions.

The lower house of the federal Congress, or Chamber of Deputies, and the single–chambered legislatures of the states and the Federal District are elected for three–year terms; their members are known as "deputies." The Senate, or upper house of the federal Congress, is elected for a six–year term. All lawmakers are elected through a system that combines winner–take–all–by–plurality in single–member districts with proportional representation (PR) by slate. They cannot be consecutively reelected to the same positions.

By two–thirds majority, the Senate appoints Supreme Court justices, choosing from three proposals made by the president. Similarly, the legislatures of the states and the Federal District appoint the justices of their own Superior Courts, choosing from a proposal made by their respective executives.

Most of the 2439 municipalities elect their local officials by a mix of plurality and pr slate, but in the state of Oaxaca, 419 of its 570 municipalities have opted to elect their officials by traditional methods. Municipal presidents (mayors) cannot be consecutively reelected; they usually serve three–year terms. The Federal District is divided into 16 boroughs, each of which elects a "borough head" by plurality to a three–year term in office; he/she can never be reelected to the same position.

The Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) runs federal elections. It is headed by a General Council, whose voting–members (usually from academia, journalists, or lawyers) are appointed in the lower house of Congress by a two–thirds majority.4 Representatives of the registered political parties sit as non–voting members on the IFE General Council as well as on its state and local councils. Ordinary citizens staff the polling booths, count the ballots, and record the results in official minutes. Their job is supervised by representatives of the political parties and/or registered national or international observers; the former can have their objections noted in each polling booth's minutes.

In state, Federal District, and municipal elections, institutions and procedures are very similar to the federal ones. Each state, as well as the Federal District, has an electoral institute or council and an electoral tribunal, both appointed by their respective legislatures, to run and scrutinize their own elections, respectively.

The Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary is a specialized court that hears cases involving federal elections, acts as an appellate court for state, Federal District, and municipal elections, and is the highest authority in the land for electoral affairs. Consequently, it can revoke the electoral institutes' decisions and tallies. Its judges are appointed by the Senate by a two–thirds majority, choosing from proposals from the Supreme Court.5

Social and Economic Conditions

Mexico is an overpopulated, developing country with a middling average income and extreme social and regional inequalities. More than 105 million inhabitants reside in Mexico, and around 11 million migrants live abroad, particularly in the United States of America (U.S.). Figure 3 presents some social indicators and also shows some advances made since 1990.

In 2005, the gross national product (GNP) was US$768 billion, and per–capita gross national income (GNI) was US$7 310. In that same year, health and education expenditures amounted to 6.5 percent and 5.8 percent of GNP, respectively. Income is extremely concentrated, with 20 percent of the population receiving 55 percent of GNI. Therefore, poverty is still remarkably high, as shown in figure 4. A Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.8031 puts Mexico among the countries considered highly developed. However, HDI regional distribution is extremely unequal, with some states as low as Syria or Cape Verde, and others as high as the Czech Republic (United Nations Development Program [UNDP], 2007).

C. MAIN FINDINGS

1. Nationhood and citizenship: Is there agreement on a common citizenship without discrimination?6

Summary answer: Much

Nationality and citizenship are fully inclusive. All people born in the land or born abroad of a Mexican parent are Mexican nationals and cannot be deprived of their nationality. Foreign nationals can apply for naturalization; they can be deprived of their newly attained Mexican nationality only under certain reasonable circumstances.7 Citizenship includes all Mexican nationals aged 18 or more; it can be lost or suspended for a limited number of circumstances, particularly for committing a felony. Foreign nationals cannot get involved in Mexican politics, and if they do, may be deported by executive order. In practice, there are no significant cases of loss of nationality or citizenship, while in recent years a handful of foreign nationals were expelled for their involvement in Mexican politics.

Nevertheless, some analysts consider that there are "excluded citizens": indigenous people who because of their language or social marginalization are unable to fully exercise their citizenship in practice (Castañeda and Saldívar, 2001: 9–16). Indeed, while indigenous peoples' rights have been enshrined in the Constitution, beyond this formal acknowledgment, little has been done for these peoples' advancement.

There is a strong consensus about the Constitution. The procedures for amending it are quite inclusive and impartial: a two–thirds vote in each of the federal chambers of Congress and the approval of a majority of state legislatures are required. This implies that no political party can amend the Constitution on its own. Nevertheless, the Constitution is often amended.

Since the end of the 1910–1920 Mexican Revolution, the existing institutional arrangements have been able to reconcile major societal divisions. This partly ex–plains why the country has been politically stable for decades. Violence erupted in the past, sometimes from above (for instance, when the military and the police fiercely repressed student movements in 1968 and 1971) and other times from below (for instance, when the Zapatista National Liberation Army [EZLN] took up arms in 1994). Even in such critical circumstances, the political system was able to reconcile differences, and to somehow integrate or co–opt any important dissident group. Nonetheless, since the 2006 presidential elections, three political parties and part of the population, operating under the slogan "To Hell with the institutions," do not concede legitimacy or legality to President Calderón's administration.

Mexico has no disputes about international or internal boundaries, and has no separatist movements. However, in the state of Chiapas several so–called "autonomous" municipalities run by the EZLN are in tolerated contradiction to the existing legal framework.

To adapt the Constitution and the main institutional arrangements to the new democratic conditions, in 2007 the Law for the Reform of the State was passed, encompassing five broad areas: the judiciary, electoral and democratic institutions, political regime, social guarantees, and federalism. Reforms in the first two areas have already been passed; the others are still pending. For his part, in late 2009, President Calderón sent Congress a political reform bill. Among other things, it would allow for the reelection of mayors and lawmakers, reducing the number of federal legislators, and establishing run–off elections for the presidency.

2. The rule of law and access to justice: Are state and society consistently subject to the law?8

Summary answer: Middling

The rule of law is weak, and access to justice unequal. While state and society should both constitutionally be subject to the law, in practice many legal –and illegal– loop–holes allow lawyers, politicians, officials, businesspersons, and people in general to avoid the enforcement of the law. Additionally, a number of citizens think that a law they consider unjust can be disobeyed, and that it is appropriate to evade legal sanctions whenever possible. Therefore, an array of tricks and technicalities are often used to hamper the rule of law.

Within the framework of the aforementioned restrictions, the rule of law is fairly operational throughout the entire country. Nonetheless, it is deficient for administrative, organizational, and judicial reasons; besides lack of resources, there is weak coordination among the federal and the state judiciaries. Additionally, consuetudinary justice prevailing in some states with important indigenous populations is not fully integrated into the overarching judicial system. Furthermore, their access to economic resources and social relations is instrumental in allowing the rich and powerful to circumvent the rule of law. However, at present the foremost challenge to the rule of law is the activities of powerful drug–trafficking cartels and the resulting wave of crime and violence.

Elected and some appointed officials are immune from criminal prosecution. Although their immunity can be withdrawn by the legislative, it hardly ever happens. Consequently, in practice they are usually free from criminal sanctions for any misdeeds they may commit. Lower–ranking officials must abide by a statute of administrative responsibilities. Agencies devoted to enforcing this statute can –and in some cases do– apply sanctions for wrongdoing.

Although legally judges and the entire judicial system are independent from the executive, the ways in which they are appointed and/or promoted tend to diminish their independence, particularly in several states where judges can be removed from office. The federal and state attorney general's offices and local public prosecutors ("ministerio público"), responsible for prosecuting crime, are usually negatively evaluated by the public (Instituto Ciudadano de Estudios sobre la Inseguridad [ICESI], 2006: 65).

In practice, the poor do not have equal access to justice. Since public defenders are badly paid and overworked, people able to hire private lawyers are in a better position when facing a court of law. In even worse straits are those –mostly indigenous people– whose knowledge of Spanish is poor or non–existent: even if by law they should be provided with interpreters, these are not always available. Additionally, there are virtually no statutory provisions for redressing judicial mistakes.

To improve some of these conditions, in 2008 the federal Congress passed a reform of the judiciary. It includes oral proceedings (as opposed to written ones) and beefing up the federal Attorney General's Office. President Calderón's late 2009 bill includes giving the nation's Supreme Court the faculty of submitting to Congress bills related to the administration of justice.

3. Civil and political rights: Are civil and political rights equally guaranteed for all?9

Summary answer: Middling

Even if the usual civil and political rights are enshrined in the Constitution and Mexico has signed most international human rights treaties and conventions, in practice their exercise is insufficiently guaranteed. While not generalized, cases of torture, extra–judicial executions and forced disappearances persist (Centro Nacional de Comunicación Social [Cencos], 2007: 48–50; Red Nacional de Organismos Civiles de Derechos Humanos Todos los Derechos para Todas y Todos [Red TDT], 2006:14–16).

The Mexican people are largely free from physical aggression by representatives of the state. However, due to a rise in crime, the state is growingly incapable of guaranteeing security to its citizens. Additionally, law enforcement is weak, and most crimes go unpunished.

The freedoms of movement, expression, association, assembly, and religion are guaranteed by law, and quite well protected in practice. The freedom to use their native language and to practice their own culture is guaranteed to indigenous peoples, but their presence in the fabric of society is actually diminishing.

Journalists and defenders of human rights and the environment are frequently harassed or intimidated and sometimes murdered. Generally these acts of repression are attributed to obscure private interests and not directly to the state (Cencos, 2007: 27; Red TDT, 2006: 45).

In recent years, some bills were passed to improve these situations. Nonetheless, much has yet to be done to fully implement civil and political rights without discrimination.

4. Economic and social rights: Are economic and social rights equally guaranteed for all?10

Summary answer: Middling

The 1917 Mexican Constitution was the first in the world to grant economic and social rights. However, implementation has been far below expectations, due in part to underdevelopment and in part to disinterest among the ruling class. Economic and social rights are much more accessible for people working in the formal sector of the economy (public administration and well–established private firms and companies) than for those working in agriculture or the broad informal sector of the economy. In addition, people living in rural areas, indigenous people, domestic and international migrants, the illiterate, and, generally speaking, the poor have limited access to economic and social rights.

Access to work is guaranteed by the Constitution, but in practice depends on the market. Labor laws guarantee many rights to those already employed in the formal sector, including pensions and other forms of social security. Nevertheless, women are being paid on average 20 percent less than men doing the same kind of work (Garza and Salas, 2007: 55).

Access to adequate food, shelter, and clean water is legally guaranteed, but in practice huge social and regional differences exist. Although in decreasing numbers, part of the population, particularly children, is undernourished. Many dwellings are built with non–solid materials, or lack solid floors or sanitation. More than 10 percent of dwellings do not have clean water, and almost 5 percent do not have electricity (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2007: 66).

Health care is accessible to virtually the whole population, but with disparities in the quality of service received. Those with the means to go to private doctors generally receive the best and most prompt attention. Those formally employed –and therefore with health insurance– can expect a reasonable degree of good attention. People with no health insurance can resort to virtually free–of–charge and consequently overcrowded clinics and hospitals in which all the necessary medications and equipment are not always available. Vaccination plans and preventive medicine have been quite effective in recent decades. However, indigenous peoples and residents of rural areas have a lower life expectancy than urban dwellers (Poder Ejecutivo Federal [PEF], 2007: 160).

Access to education from kindergarten to high school is also guaranteed and free of charge in public schools. Three out of four children of the appropriate age attend kindergarten, and virtually 100 percent go to primary school. The number of children and young people enrolled in middle school, high school, and college has greatly increased in the last two decades; part of this rise is due to private schooling. Yet, among the adult population illiteracy is around 9 percent, and average schooling is at 8.5 years (Presidencia, 2007: 275). Education on the rights and responsibilities of citizenship, known as "civic formation," was somewhat disregarded during the 1990s and the beginning of the twenty–first century, but has recovered its due importance under Calderón's administration.

Just 10 percent of the working class is unionized. Most unions normally act as an ally to the state, as a top–down control mechanism over the working class. Usually they do not have good practices of internal democracy, nor really represent or defend their members. However, some "independent" unions are more active in defending their members' interests.

Rules on corporate governance are scanty. Public corporations are bound by law to publish their balance sheets, announce their plans, call shareholder meetings, and elect their directors. All private companies must distribute 8 percent of their net profits among their workers. All economic units, regardless of size or kind of activity should provide information –solely for statistical purposes– to the Census Bureau, and comply with the laws on health and safety in the workplace, as well as with the –weak– laws protecting consumers and the environment. Besides those mentioned, there are no legal requirements for business disclosure to the general public or watchdog groups.

Anti–poverty programs, along with several years of economic stability, produced certain meager results in reducing poverty; however, it rose again in 2006–2008 (Rea, 2009: 2). Recently, Congress ordered that 8 percent of GDP be devoted to education; summing up public and private funding, Mexico is now near that figure. The country is nearing its self–imposed goal of ensuring that all children of kindergarten age attend school. A new health insurance system was set up in 2001 for people working in the informal sector, and it continues to grow. The Calderón administration established the so–called "new generation health care system," with the goal of pro–viding health care for the newborn.

Initiatives for reforming the pension system and the labor law are not popular. Private employees' pension plans were transferred to private pension funds in 1994; the same happened in 2008 for newly hired public employees –or of already working public employees, the few who chose voluntarily to do so. The Federal Labor Law, which regulates labor relations in the private sector, dates back to 1931; attempts to update it have been blocked from two flanks: by the unions, afraid of a reform that would democratize them and therefore suppress the power of their perennial leaders; and the workers, who fear that a reform would reduce their rights for the sake of flexibility, productivity, etc.

5. Free and fair elections: Do elections give the people control over governments and their policies?11

Summary answer: Middling

The Constitution stipulates that "The Legislative and Executive branches will be renewed by means of free, authentic, and regular elections." While since 1917 elections have been held uninterruptedly, it was barely at the end of the twentieth century that they actually became free and authentic, when equitable conditions to compete for the vote were established. Thus, elections gave citizens the real ability to choose their governments at the municipal, state, Federal District, and federal levels. However, the ability to choose is not accompanied by effective mechanisms for the citizens to control the government or public policies. In spite of some advances, decision making and public spending remain the terrain of a political class restricted in number and quite debased in the minds of the public. Electoral turnouts have declined since a record 77 J percent in the 1994 presidential elections, to 58.6 percent in the 2000 presidential election and just 44.2 percent in the 2009 legislative elections. These figures suggest a widening gap between the political class and the citizenry. Indeed, Mexico has been walking the path of a "delegative" democracy in which the citizens have the power –not always exercised– to elect their rulers and representatives, but simultaneously have very little control over what they decide once in office.

If the freedom to decide electorally was demonstrated in the 2000 presidential elections, electoral institutions' impartiality and credibility were severely questioned after the 2006 presidential race. This questioning was echoed among significant sectors of society, and prompted a broad electoral reform in 2007/2008, leveling the playing field for the political parties and banning the intervention of government and non–party agents in the electoral processes.

Registration and voting procedures are largely inclusive and accessible. Intimidation and abuse at the polling booth have been virtually eradicated, although occasionally isolated cases occur. The problem of patronage or exchanging votes for favors is more prevalent (Cobilt Cruz, n.d.). The registering of parties and candidates is fair: their access to the voters is based on a quite equitable formula for allotting airtime in the broadcast media; their freedom to campaign is fully guaranteed. With seven registered national political parties at the beginning of 2010, voters are presented with a menu of truly different political and ideological options. There are no significant problems of apportionment, i.e. all the votes count equally. The distribution of seats in legislative bodies along party lines reasonably reflects the citizens' vote; however, socially speaking, the legislative branch does not fully represent women, indigenous peoples, and, generally speaking, the poor.

6. Democratic role of political parties: Does the party system assist the working of democracy?12

Summary answer: Middling

All registered political parties support democracy. The party system has indeed contributed to democracy, promoting a series of reforms that made elections truly competitive. While until 1977 there were only four registered national political parties, in 2010 there are seven.

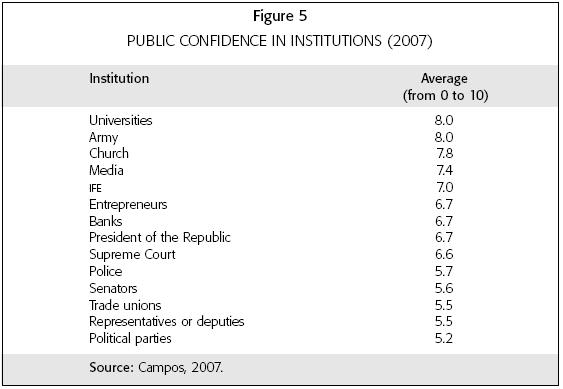

The hegemonic–party system characteristic of Mexico until the 1980s has turned into a pluralistic system with ideological diversity and reasonable degrees of freedom and competition. This new party system is still under construction, in a process aimed at defining checks and balances among the parties and forging mechanisms of cooperation to foster governance. Since the public sees the political parties as closed off in terms of participation and representation, they should enhance both their organizational capabilities and their performance in improving the people's confidence in democratic institutions (figure 5).

Mexico has long been characterized by its political stability. In the past, the party system yielded this stability through a mayoritarian or Westminster style of governance built on the hegemonic party. Nowadays, with no party holding a majority of its own either in Congress or among voters, the style of governance has turned into a consensual one that requires the agreement of at least two political parties to pass regular legislation, and of more than two political parties to pass constitutional reforms and appoint some high officials.

Every political party with at least five seats in either chamber of the federal Congress is entitled to form a parliamentary group or caucus, and therefore to receive public funding for its parliamentary activities. The opposition can hold the government accountable through several congressional mechanisms: criticizing the "state of the union" report annually sent to Congress by the executive; summoning the cabinet ministers to elaborate on this report or other issues; examining after the fact the use of the public budget; forming inquiry committees; reviewing the public accounts and administrative procedures through the Federal Auditor's Office, which is an integral part of Congress; and impeaching high officials. However, the executive is often able to hold back much information on the grounds of national security or personal privacy.

Party discipline in the federal legislature is quite strict, and varies depending on the party involved. Rules governing party discipline are not general but internal to the different parliamentary groups. There are no significant cases of floor–crossing affecting the political orientation of legislative bodies.

Some political parties have effective membership structures, and others do not. Some hold internal elections to choose their leaderships and nominate their candidates to public office. Nevertheless, even if the law protects party members' rights, the perception persists that an ordinary party member usually has little influence on how the party is run.

All registered political parties receive huge amounts of public funding; the formula used divides 30 percent of the all public funding for this budget item among the parties equally and allots the remaining 70 percent accordingly to each party's vote count in the previous election. Private contributions are restricted to just 10 percent of a party's total funding. Although the electoral institutes supervise parties' finances and regularly impose economic sanctions on them for breaking the laws regulating their financing, this area remains obscure and the people tend to perceive parties as colluded with economic interests. To keep its registration, a political party has to muster 2 percent of the vote; in late 2009, President Calderón proposed raising this threshold to 4 percent.

The law brands any use of religious beliefs or symbols for electoral purposes a crime. Additionally, it forbids misinforming or discriminating on the basis of sex, ethnicity, religion, or ideas. Nonetheless, religion, language, and culture are somehow part of electoral campaigns in some secluded areas.

7. Government effectiveness and accountability: Is government accountable to the people and their representatives?13

Summary answer: Middling

Mexican governments are more effective than accountable. While the federal, state, and Federal District governments are usually quite effective in fulfilling their basic duties, municipal governments' effectiveness varies greatly depending on their size and resources. Particularly, the federal government manages information, trained personnel, financial and material resources, technical capabilities, and planning and organization in most areas of public policy. Nonetheless, improvisation, corruption, and frequent policy switches hamper governmental performance at all levels. Public security is one main area in which the effectiveness of all levels of government is well below average.

On the other hand, the only direct way people have to keep governments accountable is through their votes, and hence the threat of not reelecting a party already in office; but as officials of the executive branch can never been reelected to the same office, a negative vote by the people does not personally affect them. The federal, state, and Federal District governments are formally accountable only to their respective legislatures. Municipal governments are accountable both to their town councils and the legislatures of their respective states. Legislatures can impeach high–ranking officials, which rarely happens, but cannot vote governments out of power for purely political reasons.

President Calderón has received an approval rate of about 60 percent since his inauguration (Consulta Mitofsky various dates). This figure must be placed in con–text. Figure 5 shows that the presidency and other governmental agencies are far short of being the most respected institutions in Mexico. On a scale of 0 (minimum) to 10 (maximum) the presidency gets an average grade of 6.7, behind the universities and the army (8), the church (7.8), the media (7.4), and the IFE (7). Other branches of government like the Supreme Court, the police, and senators and deputies rank even lower.

Appointed officials exert effective control over the departments under their charge. Their control is usually based on personal allegiance rather than institutionalized rules. A career civil service for all branches of the federal administration was created in 2004, but is not yet fully developed.

Congress has broad powers to initiate, scrutinize, and amend legislation. Until 1997, it was the executive branch that presented most of the bills passed; nowadays, individual lawmakers –generally with the support of their respective parliamentary groups– introduce most of the bills that are passed. The lower chamber has an autonomous agency –the Federal Auditor 's Office– to review public accounts and to impose sanctions when appropriate; however, this agency has not yet achieved its due authority. The two chambers of the federal Congress annually pass the federal tax law determining the federal government's revenue. Passing the yearly budget and approving the usually belated public account of expenditures are tasks solely for the lower chamber. Although much noise is made and pressure brought to bear each year by opposition lawmakers when these issues reach the floor, the truth is that congresspersons have no technical capability or support for really objecting to, or substantially modifying, the executive's budgetary proposals.

Measures in this area are part of an ongoing political process giving more and more effective powers to the legislative. Further measures can be derived from the aforementioned reform of the state, one of whose goals is to improve the relation–ship between executive and legislative. President Calderón's late 2009 bill includes creating the possibility of citizens' putting a bill before the federal Congress, as well as allowing the executive to submit two preferential bills each year that Congress would have to vote on within that year.

8. Civilian control over the military and police: Are the military and police forces under civilian control?14

Summary answer: High

Until 1946, Mexico was one of the most militarized countries in the world. In that year, the last general/president handed power over to a new civilian elite headed by the PRI. Since it was the armed forces themselves who designed the methods of transition to civilian rule, they were able to keep large amounts of functional autonomy and immunity from regular justice.

Nowadays, the military are subject solely to the president, without interference from other branches of government. Reciprocally, the president defends the military's autonomy and prerogatives. This kind of interrelation is undemocratic. Three military men sit in the federal cabinet: the ministers of defense and of the navy and the head of the president's Joint Chiefs of Staff. Congress has never questioned either the laws governing the military, or their budget or prerogatives. The military justice system is autonomous, and in practice the military protect each and every one of their members from civilian authorities. Additionally, access to information about the military is usually restricted, although there has been some degree of disclosure in recent years.

Political life is usually free from military interference, except when matters involve the armed forces directly. Indeed, the military holds silent political power that gives it veto power over decisions that could affect it. For instance, it has prevented the president from appointing a civilian as minister of defense. It has successfully opposed Mexico's participation in United Nations peacekeeping operations. It has not published any White Book, now a common practice in other Latin American countries, and until recently it has been able to avoid public scrutiny of its annual reports. Nonetheless, the public has confidence in the military: they rank second on public opinion polls exploring the people's confidence in institutions (figure 5).

The police forces are totally dispersed and decentralized. There are two federal police agencies: the Federal Police (mostly preventive, created at the end of the 1990s) and the Ministerial Police (mostly investigative, created at the beginning of this century), which have proven to be relatively effective. Additionally, every state –as well as the Federal District– has at least two police forces, and many municipalities have their own police. Consequently, in 2006 there were 1661 police bodies in Mexico. Dispersion hampers professionalism and induces corruption.

The legislatures and the citizenry have little control over the police. Police forces are in practice subordinated only to their corresponding executive authority. In addition, it is known that inside the police there are "brotherhoods" that in part manage them, and so remove them from institutional control. In some cases, organized crime has infiltrated police agencies, with crooked police officers working for drug traffickers. In some states and at the federal level, supervisory bodies have been set up for monitoring police activities, but these are just embryonic and mainly symbolic. Due to its corruption and ineffectiveness, the police rank last in surveys on people's confidence in institutions (figure 5).

The composition of the military, the police, and the security services reflects quite well the social composition of society at large. In most cases, officers are indeed from very humble origins. Military or police careers provide them with a means of upward social mobility. The same cannot be said of the rank and file, which in the case of the police tend to supplement their meager incomes through bribes and corruption.

The country is not free from groups using illegal violence. Although in diminishing numbers and importance, in some rural areas paramilitary units are still used to repress peasant movements. There are also some guerrilla groups: one is the EZLN, which after initially waging war against the federal government, later became essentially a peasant organization devoted to controlling some municipalities in the southxern state of Chiapas. Another, recently more active, is the People's Revolutionary Army (EPR). Additionally, scantily regulated private security agencies are on the rise due to police ineffectiveness; some of them or their members occasionally commit illegal acts.

However, the main problems in the area of extra–legal violence are organized crime and the drug cartels, which have been able to build what amounts to paramilitary organizations with great firepower. To confront them, President Calderón has engaged the military; this move has raised concerns about protection of human rights. Under the so–called Mérida Initiative, Mexico's military, police, and intelligence services are receiving financial and technical aid from the U.S.

In the arena of national and public security, there is little communication between civil society and government. Reforms in these areas are usually carried out without consulting the public. In 2009 and 2010, the federal and the state governments began airing the possibility of consolidating the many municipal police forces into stronger, unified state–wide police forces.15

9. Minimizing corruption: Are public officials free from corruption?16

Summary answer: Little

In spite of laws and efforts to minimize it, corruption is still endemic in Mexico. In the last few years a number of measures have been adopted to foster honesty and good governance, particularly at the federal level,17 with most of the states lagging well behind. Nevertheless, the separation of public office from party advantage and personal and family business interests by office holders is far from complete. Bribery favoritism in granting government contracts, and bad administrative practices prevail, with costs higher in Mexico than in comparable countries (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2007).

Rules and procedures for financing candidates to public office do not effectively prevent their potential subordination to vested interests, particularly if they win. Although private financing is restricted and campaign spending has caps, business, corporate, or mafia interests can illegally finance a candidate of their choice with hopes of not being caught. If caught, the political party receiving illegal funding will just pay a fine, generally without losing the posts they won in the process.

There are no norms to regulate lobbying or prevent the influence of private interests on public policy. Big corporations have great influence on the determination of public policies, as well as on blocking public policies that hurt their interests.

Consequently, Mexicans do not generally believe public officials free of corruption (PEF, 2007: 61). While under Fox's administration great attention was paid to fighting corruption, during the current Calderón administration, there has been no mention of new, specific actions for fighting corruption beyond already existing ones.

10. The media and open government: Do the media operate in a way that sustains democratic values?18

Summary answer: Middling

Advances have been made in guaranteeing the freedoms of information and opinion through the mass media. The state no longer owns or dominates the media as did for most of the twentieth century; additionally, it has lost its former ability to influence and manage journalists' activities. Public affairs are now monitored more; the media express the public's concerns; op–ed spaces have opened up to political parties, their candidates, and analysts with different orientations.

Nonetheless, the media have not fully contributed to the formation and maintenance of democratic values.19 They have not fostered substantial debate or thinking about public affairs. On the contrary, since the media tend to focus on negative aspects of politics and politicians, they have generated public distrust, thus driving citizens away from politics. Indeed, the media have emphasized the sentimental, emotional aspects of politics rather than its cognitive, rational, informational aspects; and public judgment of politics has often been oriented by disguising as information what is truly just the opinion of the corporations that own the main media outlets (Trejo, 2004: 95–124).

The media are legally independent from the government. However, extreme concentration of their ownership hinders their pluralism and contribution to democracy. Just two broadcasting companies control more than 80 percent of all TV stations (SCT, 2004). The media basically represent their owners and announcers, and social sectors that share interests with them. Investigative journalism is just developing today. No significant advances have been made for protecting journalists from harassment, intimidation, and even murder (Ballinas, 2009:15). Private citizens are virtually helpless in case of intrusion by the media, and redress procedures are ex–pensive and long and drawn out.

In 2007, a Federal Law on Radio and Television was passed. It addressed some social demands against media monopolies, but in balance benefits the dynamics of power and concentration in the hands of the big media corporations. Today, a broad debate is underway about how to improve the media and its democratic role.

11. Political participation: Is there full citizen participation in public life?20

Summary answer: Little

Citizen participation has advanced in the last 15 years, as shown by laws promoting it and by the rising number of civic organizations. This has not translated into full citizen participation, since citizen collaboration in the decision–making process is not yet fully accepted. Therefore, participation of the entire citizenry in the country's public life is still slight.

In 2004, a Federal Law to Foster Activities of Civil Society Organizations was passed. It stipulates that civic organizations (CSOs) can be officially registered and obtain certain benefits from the state. In the same year, a General Law for Social Development was passed, granting funding on a competitive basis to civic organizations working in this field. However, the number of civic organizations and citizens' groups is small compared to international standards: in 2007, only 5732 were registered (Registro, 2008), and about 5,000 CSOs were unregistered (Centro de Documentación e Información sobre Organizaciones Civiles [Cedioc], 2007). Most of them are truly independent from the government, although some partially depend on it for funding. Citizen involvement in this sort of organizations is not common. Conversely, popular self–help in tackling community problems and needs is quite frequent. Social movements, on the other hand, are usually an expression of radical opposition to the status quo.

Mexico is part of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Nevertheless, women's participation in public office is low –although on the rise. In the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, women occupy 18 percent and 28 percent of seats, respectively. Only 3.6 percent of mayors and 21.4 percent of all elected and non–elected high municipal officials are women (Garduño, 2008: 6). Women hold only 27.4 percent of the high– and medium–level positions in the public administration, but they are more commonly found in the judiciary (Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres [Inmujeres], 2006).

Constitutionally–speaking, all social groups should have equal access to public office. In practice, political inequality negatively affects some social groups: women, indigenous people, and, generally speaking, the poor. Additionally, electoral legislation bans independent, non–partisan candidates from running for public office (President Calderón's late 2009 bill would allow for it).

12. Government responsiveness: Is government responsive to the concerns of its citizens?21

Summary answer: Middling

No legal provisions mandate the federal government to consult the citizenry, nor create institutionalized ways for the latter to convey its concerns to the former. The federal executive is obliged to convene forums to discuss the drafting of the national plan of development, and Congress usually convenes forums on different issues. Individual citizens can submit written proposals or attend these forums, generally to no avail. Nevertheless, the relative openness of the media and the existence of opposition parties allow the government to acquaint itself with the citizens' concerns.

For their part, many states and the Federal District have passed laws allowing for referendums and popular initiatives on some issues; the few referendums already held were notorious for their low voter turnout. Additionally, at the municipal level, most states have non–partisan mechanisms for citizen participation in micro–local concerns.

There are no provisions for public representatives being available to their constituents. Many of them, using funding from the legislature, have set up modules open to the public that work more as claims and grievances bureaus than links between the lawmakers and their constituencies.

Public services are of middling quality. Regulatory agencies supervise private companies providing public services. No mechanisms exist for consultation with customers or for redress when they fail.

Citizen's confidence in the government's capability to solve society's main problems (PEF, 2007: 57–58) and their own ability to influence governmental decisions (Instituto de Mercadotecnia y Opinión [IMO], 2006) are both low, but on the rise.

13. Decentralization: Are decisions being made by the level of government most appropriate for the people affected?22

Summary answer: Middling

Since Mexico has a federal government, it should be highly decentralized. However, most state and municipal government decisions depend on the federal government allotting the needed funding. While on paper, state and local governments are gaining powers and responsibilities, they do not collect enough revenue to fully carry them out. The situation is worst for municipal governments, since they depend both on their state government and the federal government for resources. To assuage revenue shortages and alleviate dependence on the central government, municipal and state governments need to be able to levy more taxes. However, this is not being done for political reasons: local and state governments prefer the federal government to bear the electoral burden of collecting taxes (see Centro de Estudios de las Finanzas Públicas [CEFP], 2005; INEGI, 2006a and 2006b; González Anaya, 2007).

State governors and legislatures, mayors and municipal councils, and the Federal District's local authorities are regularly elected in fairly free and competitive elections. According to the federal and state Constitutions, all government actions should be carried out according to the guiding principles of legality, constitutionality transparency, impartiality and accountability. All the states and the Federal District have passed legislation granting access to public information. However, a high percentage of the public continues to perceive local and state governments as corrupt.

Cooperation among state and municipal governments has not yet been fully developed due to lack of both resources and an associative culture. There are, however, some significant and successful cases of cooperation among municipal governments in some metropolitan areas. Additionally, several associations of municipalities also exist, usually operating along party lines. Cooperation with other relevant partners remains scant, but is on the increase.

Federalism –or better said its actual implementation– is part of the agenda for reforming the state, which includes fiscal decentralization, strengthening local governments' transparency and accountability, giving them a say in planning national development, and improving cooperation among different levels of government.

14. International dimensions of democracy: Are the country's foreign relations conducted in accordance with democratic norms, and is the country free from subordination to external agencies?23

Summary answer: High

Mexico has historically been subject to considerable external conditioning factors, which its foreign policy has tried quite successfully to withstand. The main external pressures came from the United States, whose past armed interventions in Mexico left a deep imprint on the Mexican people's memory and national feeling. At pre–sent, it seems remote that the United States would use or threaten to use force against Mexico, but political and economic pressures are in play, as Mexico is extremely linked to its northern neighbor demographically, economically, geopolitically and culturally (Emmerich, 2006).

Mexico's foreign policy relies on international law and supports the development of international organizations. Mexico regards multilateral forums as an appropriate instrument to promote the peaceful resolution of controversies, foster cooperation among states, and establish conditions for worldwide peace and security. In its view, these are the best conditions for broadening Mexico's margins of independence and autonomy. Hence, it maintains a high degree of cooperation with the international system's organizations (Ojeda Gómez, 1977).

Mexico actively participated in the drafting and approval of the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man. This enthusiastic willingness disappeared during the Cold War but began to reemerge in the 1980s, when Mexico ratified the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. At present, it is one of the countries with the greatest commitment and openness toward international human rights law. Nevertheless, due to its allegiance to the principles of non–intervention and self–determination, Mexico has not assumed a militant position promoting human rights and democracy abroad (Pellicer, 2006a and 2006b). Nonetheless, an effort should be made to fully include and implement the rights protected by these international instruments in Mexico's own law and practices.

Mexico has sustained an active policy of asylum and has strongly defended the human rights of international migrants, especially of Mexican–born people permanently residing in the United States. However, it has not been able to equally protect the rights of trans–migrants (non–Mexicans crossing Mexico on their way to the U.S.).

The Mexican government seems determined to maintain the margins of action and independence that its foreign policy achieved in the past. Protecting Mexicans living abroad –particularly in the United States– and truly guaranteeing the human rights of trans–migrants within Mexico are certainly priorities. A slightly greater commitment to the promotion of democracy and human rights abroad is foreseeable, although this possibility is counterbalanced by Mexico's reticence to intervene in other countries' internal affairs. This set of current policies receives reasonable approval among the public.

D. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS

Mexico's democracy is still under construction, with significant achievements but also formidable challenges (figure 6). In short, it is slightly above medium quality and has many areas open for improvement. These conclusions should not be surprising nor disheartening, but encouraging. A slightly above medium quality democracy. This is the average of the summary answers to the overarching search questions: one "very much," two "much," nine "middling," two "little," and zero "very little."

Indeed, in most of the thematic areas explored, the results are mixed. At the legal and institutional levels, Mexico is doing quite well: its laws, public and private agencies, political parties, electoral system and institutions, and citizenry at large are quite prepared for true democracy. In most cases, the laws and institutional design are acceptable, but implementation often lags way behind, and also some legacies of an authoritarian past have yet to be eradicated from them. Public institutions have reasonable operational capabilities to fulfill their duties, but many are neither effective nor efficient.

Not surprising, for two reasons. One substantial one is that Mexico's democracy is very young, as suggested by the timeline in figure 1. Much has yet to be learned, and learning takes time. A second, incidental reason is that the research team, composed basically of Mexican, independent social and political researchers, is uncompromising in its desire for a full and functioning democracy in Mexico. The team has an ideal of democracy that is far more advanced and comprehensive than Mexico's reality is. Therefore, the team's judgments can be understood as an expression of what the Mexican people really want: a top–quality democracy.

Not disheartening, since, after all, Mexico is a democracy. Defective, it may be, but cherished by the people, who want more and more of it. In many areas, democratic achievements have indeed been reached, such as the following: guaranteeing basic freedoms; an electoral system that, regardless of many acrimonious controversies, still keeps continuously leveling the playing field upward; a party system that –even if amidst a great deal of rancor– offers real options to the voters; the creation of controlling agencies and ombudsmen; the implementation of a career civil service; greater access to public information; reforming the judiciary; and, most importantly all the relevant actors and the people voluntarily abide by the Constitution. All this suggests that deep below the bickering of day–to–day politics, Mexico's political class and citizenry have been able to adopt new ideas, institutions, practices, and attitudes gradually bringing forth democracy with virtually no bloodshed or upheavals, at the same time preserving freedom, sovereignty and political stability. This deserves credit: Mexico's gradualism and pacifism can be considered an example to countries in transition to democracy throughout the world.

Encouraging, because many areas are open for further improvement, and it seems there is enough political will to do so. For instance, according to Congress's own agenda, reforms in the areas of federalism, government regime, and social guarantees should be passed soon. Another example is the political reform bill President Calderón sent to Congress in late 2009.

In this context, the research team has some proposals of its own to beef up Mexico's democracy. They are as follows:

• Granting effective collective rights to indigenous peoples and actual access to individual rights for their members.

• Avoiding the practice of continually reforming the Constitution: each government should adhere to the Constitution, instead of the Constitution being adjusted to the government in office.

• Deepening the judicial reform by introducing jury trials.

• Improving the entire law–enforcement system.

• Introducing procedures for redressing administrative, police, and judiciary wrongdoing.

• Democratizing trade unions and integrating labor proceedings into the judicial branch.

• Introducing semidirect democracy at the federal level: referendum, popular initiative, recall.

• Introducing run–off presidential elections to give the winner greater legitimacy.

• Allowing independent candidates to run for office.

• Professionalizing the police and eradicating corruption from its ranks.

• Opening up of the military to public scrutiny, and possibly reducing its size.

• Strengthening regulatory and anticorruption agencies.

• Ensuring the broadcast media is pluralist and not concentrated in a few hands.

• Reducing the income gap between high officials and ordinary workers.

• Strengthening and expanding the career civil service.

• Strengthening federalism and state and local governments.

• Reforming the tax system so people pay the greatest part of their taxes to state and local governments, not to the federal one.

These proposals deal with administrative and political matters. A final issue must be taken into account: an equitable social and economic context is integral to any functioning democracy. Drastically reducing poverty and social marginality is an imperative. Under the current economic and social conditions, great numbers of Mexicans are living in squalor. Some of them just stand it, and become marginalized. Others migrate to the United States for a better life. Still others revolt against a political system they deem still burdened with authoritarian practices. Democracy has to provide all of them with hope: hope for a better future. This is the main challenge for Mexico's young democracy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alvarado, Arturo. 2009. "La policía, los militares, el sistema de seguridad pública y la administración de la coerción: México frente a América Latina," El Cotidiano, year 24, no. 153 (January–February). [ Links ]

Ballinas, Víctor. 2009. "Presentan informe sobre agresiones a periodistas," La Jornada, January 23. [ Links ]

Benítez Manaut, Raúl. 2005. "Doctrina, historia y relaciones cívico–militares en México a inicios del siglo XXI," in José Antonio Olmeda, ed., Democracias frágiles. Las relaciones civiles–militares en el mundo iberoamericano, Valencia, Spain, Tirant Lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Camp, Roderic Ai. 1992. Generals in the Palacio. The Military in Modern Mexico, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

––––––––––.2005. Mexico's Military on the Democratic Stage, Westport, Connecticut, CSIS, Praeger Security International. [ Links ]

Campos, Roy. 2007. Tracking poll. Confianza en las instituciones, Mexico City (September). [ Links ]

Castañeda, Alejandra and Emiko Saldívar. 2001. Ciudadanías excluidas: indígenas y migrantes en México, San Diego, California, The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California. [ Links ]

CEDIOC (Centro de Documentación e Información sobre Organizaciones Civiles) 2007 Centro de Documentación e Información sobre Organizaciones Civiles, data base available at Mexico City's Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Iztapalapa campus. [ Links ]

CEFP (Centro de Estudios de las Finanzas Públicas). 2005. "El ingreso tributario en México," www.cefp.gob.mx/intr/edocumentos/pdf/cefp00720005.pdf, accessed March 25, 2008. [ Links ]

CENCOS (Centro Nacional de Comunicación Social). 2007. Informe sobre la situación de los derechos humanos en México," www.cencos.org.mx, accessed May 17, 2008. [ Links ]

Cobilt Cruz, Elizabeth. n.d. "El clientelismo en México," doctoral thesis in social studies, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Iztapalapa campus, Mexico, in progress. [ Links ]

Consulta Mitofsky. various dates "Evaluación de gobierno. Tracking poll," www.consulta.com.mx, periodically updated. [ Links ]

Emmerich, Gustavo Ernesto. 2006. "Estados Unidos y México: cuando la geografía es destino," in Antonella Attili, comp., Treinta años de cambios políticos en México, Mexico City, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Emmerich, Gustavo Ernesto, comp. 2009. Situación de la democracia en México, Mexico City, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [ Links ]

Emmerich, Gustavo Ernesto and Alejandro Favela. 2007. "Democracia vs. Autoritarismo," in Gustavo Ernesto Emmerich and Víctor Alarcón Olguín, eds., Tratado de ciencia política, Barcelona, Anthropos. [ Links ]

EMP (Estado Mayor Presidencial). 2006. El Estado Mayor Presidencial. Cumplir con institucionalidad, Mexico City, Presidencia de la República. [ Links ]

Espinoza, Alejandro Carlos. 1998. Derecho militar mexicano, Mexico City, Porrúa. [ Links ]

García, Ariadna and Claudia Guerrero. 2007. "Pide Segob a medios mejorar contenidos," Reforma, October 10. [ Links ]

Garduño, Roberto. 2008. "Sólo 96 presidentas municipales," La Jornada, June 28. [ Links ]

Garza, Enrique de la and Carlos Salas. 2007. La situación del trabajo en México, Mexico City, Plaza y Valdés / Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [ Links ]

González Anaya, José Antonio. 2007 "Diagnóstico y reflexiones sobre el sistema de transferencias federales," Unidad de Coordinación con Entidades Federativas, Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (SHCP), Mexico City, April 18, www.eclac.org/ilpes/noticias/paginas/3/28623/11percentDiagnostico_070524_ffiscales.pdf, accessed March 25, 2008. [ Links ]

ICESI (Instituto Ciudadano de Estudios sobre la Inseguridad). 2006. "Cuarta encuesta sobre inseguridad en zonas urbanas," www.consulta.com.mx/interiores/99_pdfs/15_otros_pdf/oe_20061025_ICESI.pdf, accessed October 1, 2007. [ Links ]

IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). 2002a. Handbook on Democracy Assessment, The Hague, Kluwer Law International. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2002b. The State of Democracy. Democracy Assessments in Eight Nations around the World, The Hague, Kluwer Law International. [ Links ]

IFE (Instituto Federal Electoral). 2006. Elecciones federales 2006. Encuestas y resultados electorales, Mexico City, Instituto Federal Electoral. [ Links ]

IMO (Instituto de Mercadotecnia y Opinión). 2006. Encuesta nacional en México sobre ciudadanía, Mexico City, Instituto de Mercadotecnia y Opinión. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2006a. Finanzas públicas estatales y municipales de México, Aguascalientes, Mexico City, INEGI. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2006b. El ingreso y el gasto público en México, Aguascalientes, Mexico City, INEGI. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2007. Anuario estadístico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Edición 2006, Aguascalientes, Mexico, INEGI. [ Links ]

Inmujeres (Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres). 2006. Las mujeres en la toma de decisiones. Participación femenina en los poderes del Estado, Mexico City, Inmujeres. [ Links ]

Ojeda Gómez, Mario. 1977. Alcances y límites de la política exterior de México, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

PEF (Poder Ejecutivo Federal). 2007. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2007–2012, Mexico City, Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. [ Links ]

Pellicer, Olga. 2006a. México y el mundo. Cambios y continuidades, Mexico City, Porrúa. [ Links ]

––––––––––.2006b "Mexico –A Reluctant Middle Power?" in New Powers in Global Change, Dialogue on Globalization, Briefing Papers, Mexico City, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (June). [ Links ]

Piñeyro, José Luis. 1985. Ejército y sociedad en México. Pasado y presente, Puebla, Mexico, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana/Universidad de las Américas, Puebla. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República. 2007. Primer informe de gobierno 2007. Anexo estadístico, n.p., no publisher listed. [ Links ]

Price Waterhouse Coopers. 2007. Delitos económicos 2007. Gente, cultura y controles, Mexico City, Price Waterhouse Coopers. [ Links ]

Rea, Daniela. 2009. "Aumenta 4.4% la pobreza extrema," Reforma, July 19, p. 2. [ Links ]

Red TDT (Red Nacional de Organismos Civiles de Derechos Humanos Todos los Derechos para Todas y Todos). 2006. "Informe 2006," www.derechoshumanos.org.mx, accessed May 17, 2008. [ Links ]

Registro Federal de las OSC. 2008. "Registro Federal de las Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil," www.osc.gob.mx/portal/buscador.asp, accessed June 18, 2008. [ Links ]

RESDAL (Red de Seguridad y Defensa de América Latina). 2008. "Atlas comparativo de la defensa en América Latina," Buenos Aires, Resdal, www.resdal.org, accessed May 7, 2009. [ Links ]

SCT (Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes). 2004. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes, www.cofetel.gob.mx/wb/Cofetel_2004/Cofe_infraestructura, accessed June 15, 2008. [ Links ]

Sedena (Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional). 2005. La Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional en el inicio de un nuevo siglo, Mexico City, Sedena/Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Semar (Secretaría de la Marina). 2004. Libro de políticas de la Armada de México, Mexico City, Armada de México. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2005. Armada de México: compromiso y seguridad, Mexico City, Secretaría de Marina/ Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Trejo Delarbre, Raúl. 2004. "Democracia cerrada: política y políticos en el espectáculo mediático," in Luis Maira et alii, Democracia y medios de comunicación, Mexico City, Instituto Electoral del Distrito Federal (IEDF). [ Links ]

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2007. Informe sobre el Desarrollo Humano México 2006–2007, New York, United Nations. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2007. World Development Indicators 2007, World Bank (CD–ROM). [ Links ]

* The research project reported here was supported by a grant from Mexico's National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt). Of course, Conacyt cannot to be held responsible for its results.

** The research team was made up of Víctor Alarcón Olguín, Pablo Javier Becerra Chávez, Jessica Bedolla, Raúl Benítez Manaut, Enrique Cuna Pérez, Enrique de la Garza, Gustavo Ernesto Emmerich (team leader), Enrique Flores Ortiz, Mariana Hernández Olmos, Miguel González Madrid, Alfonso León Pérez, Gustavo López Montiel, Luis Eduardo Medina Torres, Mónica Miguel Cárdenas, Francisco Olguín Uribe, Sergio Parra Menchaca, Gabriel Pérez Pérez, Juan Reyes del Campillo, Cristina Sánchez Mejorada, and Pablo Vargas González.

1 IDEA'S methodology belongs to the public domain. idea has no bearing on nor responsibility for this report, which was independently conducted.

2 Other principles could be added, like freedom, popular participation in government, and equitable distribution of power (Emmerich and Favela, 2007).

3 Founded in 1929 as the National Revolutionary Party (PRN), it changed its name in 1938 to Party of the Mexican Revolution (PRM), and in 1946 to the PRI.

4 The electoral councilors who conducted the 2006 elections had been appointed in 2003, at the proposal of the PAN and PRI blocs in the lower chamber of Congress; on that occasion, the PRD deputies refused to cast their votes as a protest against what they alleged was an "imposition" by these two political parties. Most of those councilors were replaced in 2008 by the Chamber of Deputies, in what seemed to be a sort of punishment.

5 The judges who supervised the 2006 electoral process had been appointed in 1996 and had gained prestige for resolving cases with equanimity before they were accused of bias by López Obrador.

6 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) inclusiveness of nationality and citizenship; b) acknowledgement of cultural differences and protection of minorities; c) consensus on state boundaries and constitutional arrangements; d) ability of the Constitution and political institutions to reconcile social divisions; e) procedures for amending the Constitution; and f) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

7 For instance, by not living in the country for more than five years or using a foreign passport.

8 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) the extent of the rule of law; b) public officials adhering to it; c) independence of the judiciary; d) equitable access to justice, due process and –if needed–redress; e) impartiality in the criminal justice and penal system; f) people's confidence in the legal system; and g) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

9 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) physical violence against persons; b) equal protection of the freedoms of movement, expression, association, and assembly; c) freedom to practice one's own religion, language, or culture; d) harassment or intimidation of human rights activists; and e) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

10 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) access to work and social security without discrimination; b) access to food, shelter, clean water, health care, and education; c) freedom for trade unions; d) rules on corporate government; and e) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

11 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) appointment to public office by popular, competitive election and parties alternating in office; b) registration and voting procedures; c) procedures for registering parties and candidates and for their access to the media and the voters; d) the range of choices available to the voters, equal weight of their votes, and representative composition –both politically and socially– of the legislature and the executive; e) voter turnout and acceptance of election results; and f) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

12 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) freedom of political parties; b) effectiveness of the party system to form and sustain governments; c) freedom of opposition political parties in Congress to hold the government accountable; d) rules regulating party discipline in Congress; e) influence of party members on party policy and candidate selection; f) prevention of parties' subordination to special interests; g) ethnic, religious, and linguistic divisions across parties and their electorates; and h) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

13 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) government capability of controlling or influencing matters important to the people's lives; b) people's confidence in the government's and the president's capability, and in their own ability to influence government; c) type of control exercised by elected officials over the public administration; d) congressional powers to effectively legislate, oversee the executive, and hold it to account; e) procedures for approval and supervision of taxation and public expenditure; f) access to public information; and g) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

14 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) effectiveness of civilian control over the armed forces, and freedom of political life from military involvement; b) public accountability of police and security services; c) social composition of the army, police, and security services; d) operation of paramilitary units, private armies, warlords, and criminal mafias; and e) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.

15 For further reference in this area, see Alvarado (2009), Benítez Manaut (2005), Camp (1992 and 2005), Estado Mayor Presidencial [emp] (2006), Espinoza (1998), Piñeyro (1985), Red de Seguridad y Defensa de América Latina [Resdal] (2008), Secretaría de Defensa Nacional [Sedena] (2005), and Secretaría de la Marina [Semar] (2004 and 2005).

16 The specific questions for this thematic area refer to: a) separation of public office from personal/family business and interests; b) arrangements for avoiding bribery; c) rules to prevent the subordination of elections, candidates and elected representatives to vested interests; d) undue influence of corporations and business interests over public policy; e) people's perception of corruption; and f) measures being taken to remedy problems in this area.