Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Norteamérica

On-line version ISSN 2448-7228Print version ISSN 1870-3550

Norteamérica vol.4 n.1 Ciudad de México Jan./Jun. 2009

Análisis de actualidad

Philanthropy and the Third Sector in Mexico: The Enabling Environment and Its Limitations

Filantropía y el tercer sector en México: un ambiente propiciatorio y sus limitaciones

Michael D. Layton*

*Philanthropy and Civil Society Project (PCSP), ITAM. layton@itam.mx.

Abstract

Why is Mexico's third sector underdeveloped? Despite the importance of this question, there is no persuasive answer. The usual mono–causal explanations –such as historical trajectory or lack of civic culture– are inadequate. A better way to address this question is applying the concept of an enabling environment for civil society. This encompasses empowering legal and fiscal frameworks, an effective accountability system, adequate institutional capacity of organizations, and availability of resources. The article offers an assessment of where Mexico stands in relation to these five components and argues that on each count they are unfavorable and/or underdeveloped. In addition, the author argues for including a sixth element: the cultural context for philanthropy and civil society. Based on original survey results, he demonstrates that key values and habits inhibit efforts to strengthen civil society and must be taken into account in any effort to understand or change the status quo. The article concludes with a reflection on how Mexican civil society can begin to change its unfavorable context, beginning with the need for stronger mechanisms for greater accountability on the part of organizations.

Key words: Philanthropy, enabling environment, civil society, accountability system.

Resumen

¿Por qué se ha desarrollado poco el tercer sector mexicano? Apesar de la importancia de esta pregunta, no existe una respuesta persuasiva. La explicación monocausal habitual, la de la trayectoria histórica o la de la falta de cultura cívica, es inadecuada. Una mejor manera de abordar la cuestión es aplicando el concepto de un ambiente propiciatorio o facilitador para la sociedad civil, que significa dar más poder a los marcos fiscales y legales; un sistema de transparencia efectivo; una adecuada capacidad institucional de las organizaciones; y la disponibilidad de recursos. Este artículo presenta un análisis sobre dónde se encuentra México en relación con estos elementos y argumenta que en cada uno hay características poco propicias o subdesarrolladas. Además, el autor piensa que debe incluirse otro elemento: el contexto cultural para la filantropía y la sociedad civil. Con base en resultados de encuestas originales demuestra que los valores clave y los hábitos inhiben los esfuerzos por fortalecer a la sociedad civil, por lo que se debe tomar en cuenta cualquier esfuerzo para entender o cambiar el statu quo. El artículo concluye con una reflexión sobre cómo puede comenzar a cambiar este contexto poco favorable, empezando con la necesidad de contar con mejores mecanismos de transparencia de parte de las organizaciones.

Palabras clave: Filantropía, ambiente propiciatorio, sociedad civil, sistema de rendición de cuentas.

INTRODUCTION

Why is Mexico's third sector underdeveloped? The data provided by the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project as well as domestic inventories and listings of organizations consistently demonstrate a small sector for a nation of over 100 million people boasting the world's twelfth–largest economy. This is an urgent question not just for academics but for civil society leaders, funders, and all those concerned with Mexico's democratic, social, and economic development.

Let us examine the list of usual suspects blamed for the relatively small size of Mexico's not–for–profit sector, both in terms of the charges leveled against them and the evidence presented.

• History: One obvious place to look is Mexico's history. The Mexican government has a longstanding hostility toward an independent civil society, dating back to the nineteenth century and most recently expressed in the form of corporatism, where all associational forms were subsumed under the banner of the state. In a famous essay, Mexico's Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz termed the government a "philanthropic ogre," an ogre in terms of its repressive policies, but philanthropic because it promised to care for its citizens. But given the rapid rise of civil society in other countries emerging from more brutal forms of authoritarian governments (e.g. Chile, Brazil, the newly independent states, etc.), the dead hand of history seems to lose its deterministic character.

• Lack of civic or philanthropic culture: Early on in almost any interview about philanthropy in Mexico, one will hear the observation that, "We just don't have a culture of giving" (Moreno, 2005: Chapter 7). Simply chalking something up to "culture," without a clear definition of what culture is and without an examination of the mechanisms by which culture shapes societal institutions and behavior is unsatisfactory both for academics and advocates. Without a definition and an explanatory mechanism, there is no traction for studying and understanding the key factors involved, nor is there much hope of changing outcomes.

• Inadequate measurements: Many advocates and some researchers blame measuring instruments. Domestically, there is no universally agreed–upon census or inventory of organizations. The Johns Hopkins University (JHU) study is criticized for using a U.S. framework to assess a distinct reality, so it undercounts the number of organizations because it over–emphasizes the formality of the organizations and misses the majority of groups with no formal legal status, such as church–based endeavors or neighborhood associations (Verduzco, 2003: Chapter 5, esp. 101–104). Even taking into account this criticism, the sector is still woefully small. More importantly, this criticism begs the question, why are so few organizations formally instituted?

• Lack of professionalization among organizations: Many funders and government officials observe –or complain– that organizations lack capacity and professionalization. The underlying argument is that if only groups knew how to fundraise, or had stronger boards, or strengthened their management systems or leadership, they would thrive. But in itself this is an unsatisfactory story line (Lagloire and Palmer, 1999). If you push on this explanation a bit and examine why they lack professionalization, raising your sights from the micro–organizational level, you quickly encounter a slew of contextual factors, beginning with a lack of available resources. Without funds, it is difficult to pay for training, or hire and retain professional staff, or comply with an onerous and complex set of legal and fiscal requirements.

The problem is that each of these assessments comes from a limited perspective, rather like the allegory of the three blind men presented with an elephant and asked to identify what it was: one grabbed the trunk and pronounced the creature a snake; the second placed his hands on the elephant's sides and said it was a wall; and, the third encountered the elephant's leg and asserted it was a tree. The solution is a more systemic approach to understanding what it takes to generate and maintain a vibrant not–for–profit sector.

The concept of an enabling environment provides a promising theoretical framework for understanding this problem. This concept has been used to draw attention to the importance of contextual factors in business promotion (Herzberg, 2008) and the capacity of development organizations (Brinkerhoff, 2004; Lusthaus et al., 2002). The argument in favor of its use is that it encourages donors in particular to understand and address the key contextual factors that might impede the success of their project–based interventions. Its application to the third sector has been more limited. In a speech in 2003, Barry Gaberman, then of the Ford Foundation, identified the following five elements as "the components of an enabling environment that would enhance the development of a vibrant civil society and its sustainability" (Gaberman, 2003: 6):

• a legal framework that empowers groups rather than shackling them;

• a tax structure that provides incentives, not penalties;

• an accountability system that builds confidence in civil society organizations;

• the institutional capacity to implement effective activities; and,

• the availability of resources to undertake these activities.

Gaberman's contribution is to offer a set of factors that make up the enabling environment for civil society more generally. Each element plays a key role in encouraging or inhibiting the creation and maintenance of organized civil society.

In this article, the author will offer an assessment of where Mexico stands in relation to these five components, based on a range of original research and a review of relevant –if severely limited– data. As with any essay written about Mexico in particular and perhaps developing countries in general, one must lament and attest to the fact that the data on not–for–profit institutions is limited and at times nonexistent. This reflects not only the youth of the sector and the unfamiliarity of many governmental, statistical agencies with it, but also the relative low priority it suffers. Nevertheless the Philanthropy and Civil Society Project has managed to create and assemble enough information to offer a portrait of this sector, as seen through the categories Gaberman offers.1

This article presents three key arguments. The first major one is that each of the five elements of the enabling environment for the third sector in Mexico is relatively unfavorable and/or underdeveloped:

• The legal framework imposes unnecessary burdens and limitations on the legal incorporation of organizations.

• The fiscal framework imposes more costs than benefits, and is a disincentive to organizations' formalizing their activities.

• At present, the accountability system for organizations is restricted to vertical forms of reporting between individual organizations and government regulators and donors. Clearly this system has failed to induce confidence in the government officials, the media, many donors, as well as the larger public. A few noteworthy initiatives have attempted to generate discussion and offer options for promoting greater transparency, but they are in their infancy.

• The institutional capacity of organizations to generate high–impact activities, or even survive, is limited by a series of contextual factors, including: financial uncertainty, limited use of networks, and the lack of adequate training opportunities.

• The availability of resources is severely limited by a paucity of donor institutions, a limited –although growing– number of corporate initiatives, a lack of governmental support, and low levels of individual giving.

The concept of the enabling environment for the third sector in Mexico improves our understanding by offering a systematic set of criteria for the evaluation of the context in which organizations operate.

The article's second major argument is that a key element is lacking in this conceptualization of the enabling environment: the cultural context for philanthropy and civil society. I define culture as "the values, attitudes, beliefs, orientations, and underlying assumptions prevalent among people in a society" (Huntington, 2000: XV). Based on the results of the first national public opinion poll on giving and volunteering in Mexico, the National Survey on Philanthropy and Civil Society (known by its Spanish acronym, Enafi), the author will demonstrate that key values and habits undermine attempts to strengthen the enabling environment for civil society and must be taken into account in any effort to understand or change the status quo.

The article will conclude with its third major argument: that the third sector in Mexico can only begin to change its unfavorable enabling environment by establishing stronger mechanisms for greater accountability. These mechanisms must go far beyond improved transparency, too often is viewed as an end in itself rather than one aspect of how accountability is established. Instead, organizations must strengthen their links to their key stakeholders not only in terms of the provision of information but also in terms of their impact on Mexico's most pressing development challenges.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

In an effort to offer a comparative and quantitative assessment of how the legal environment influences the size of civil society in thirteen countries, Salamon and Toepler (2000) constructed a favorability index for the legal framework. Of the nations assessed, Mexico was one of only four that scored "high" on the favorability index. In the graph of size of sector as measured by percentage of GDP versus favorability, 11 of the countries track a very clear, positive correlation: Mexico was one of two clear outliers, although Spain also fell into the area of High Score, Small Sector (Salamon and Toepler, 2000: 15) (Ireland was the other, with a relatively large sector despite a relatively unfavorable legal environment). The authors offer two explanations for this: "enabling laws are no guarantee for actual enablement" or that its favorable laws have not had enough time to take effect (Salamon and Toepler, 2000: 16).

Since that assessment, the Mexican Congress has enacted the Federal Law to Encourage the Activities of Civil Society Organizations (known by its Spanish acronym as LFFAOSC). Perhaps its single most important contribution is that it recognizes that the organizations' activities are of public interest and requires that the federal government seek to encourage them. Since its passage in 2004, the federal government has moved to implement the law in conjunction with an Advisory Council comprised of government officials, civil society leaders, and academics. A registry of organizations has been established, which serves as a prerequisite for access to federal funds. This has also promoted much greater transparency in the provision of governmental funding for the sector.2

While the provision of government financial support is clearly important, this is only one aspect of a favorable legal framework. An important limitation of the law is that while it mandates government agencies to encourage CSO activities, it cannot enforce that mandate and does not in itself make the legal framework more favorable. In addition, this mandate has been narrowly perceived by many both inside and outside government as providing a channel for funding and little else. The established structure for project financing via the National Institute for Social Development (Indesol), a key governmental link to CSOs in Mexico, reflects closely that of Chile, about which De la Maza comments, "The format based on projects of brief duration allocated by competition reduces such participation [to] a mere instrumental dimension … and fails to allow a more permanent type of association to be built" (2005: 343).

The aforementioned law does little to address one of the legal framework's main problems, its complexity, and embodies one of the most troubling tendencies in legal reforms, the multiplication of registries for not–for–profits.

• Various legal forms, which differ from state to state.

• The legal standing of IAP or IBP implies a relationship with regulatory bodies established in the 19th century and that exist in roughly half of Mexico's states, which are generally called Juntas de Asistencia Privada (JAP), or Private Social Services Oversight Commission.3

• In addition, a new Social Services Law (Ley de Asistencia Social)/IDF another registry.

• Largely overlapping requirements for documentation and reporting.

On the face of it, the assertion that a favorable or empowering legal framework should lead to a stronger and more vibrant not–for–profit sector seems indisputable. After all, the imposition of burdensome regulations is often a first step by authoritarian governments to inhibit an independent sector. Nevertheless, this assertion runs into three main problems (on this point see Irish et al., 2004; Salamon and Toepler, 2000: 2–3; Heinrich and Shea, 2007). First, there is no clear consensus on what a favorable legal environment entails. Given the complexity of the law and the diversity and plurality within the sector, a single law might encourage one type of organization while impeding the growth of another sort. Second, as in the case of Mexico and other Latin American countries, the gap between what is written in law and how those rules are interpreted and enforced can make all the difference (Grindle, 2005: 420). Third, given the multiple and integrated factors that make up the enabling environment for civil society, a favorable legal environment in itself is likely to be insufficient to encourage a stronger civil society. Beyond what is stated in the legal and fiscal framework, a larger issue looms: what is government's underlying relationship to civil society? (De la Maza, 2005: 332–333). As De la Maza observes, "The evidence suggests that legal and tax mechanisms, though important, are neither a radical impediment to, nor a magic wand for, increased philanthropic action per se" (2005: 332). What might be at work here is a question of causation. Perhaps a favorable legal framework is more likely to be either a reflection of a healthy civil society sector, or of a government that endorses the idea of such a sector, or both.

The net result of these layers of legal frameworks is that organizations feel far from empowered, as is Gaberman's standard. On the contrary, many find that the costs of becoming formally established outweigh the benefits. Many businesses have come to the same conclusion, and thus the informal or grey economy flourishes in Mexico. As the World Bank indicates in its study Doing Business 2008, the government imposes onerous and costly requirements, especially in the two key areas of personnel, which generally represent the single largest budget item for CSOs, and fiscal compliance, which is the single most important governmental incentive offered to not–for–profits.

TAX STRUCTURE

Tax incentives in the Mexican fiscal framework are fairly favorable on paper, and include tax deductibility of donations and tax exemption under the income tax law (or LISR, its acronym in Spanish), but there is no estate tax and only limited exemption from value added tax (USIG, 2008: 2). It is important to bear in mind that high levels of informality greatly weaken the impact of fiscal incentives: if few citizens are taxpayers, as is the case in Mexico, then making donations tax deductible loses its punch; if organizations do not receive such donations and can exist informally without paying income tax, than tax–exempt status loses its appeal, especially when these limited benefits are weighed against the high costs of obtaining and maintaining that status.

The Philanthropy and Civil Society Project (PSCP) was part of a two–year effort to conduct a national dialogue and develop a fiscal agenda to strengthen civil society.4 The major conclusions of that work were that organizations perceive the fiscal framework as overly burdensome; they have limited organizational and administrative capacity to comply; most accountants, lawyers, notaries, and even many tax authority functionaries do not have an adequate understanding of these complex rules. The net result is a great imbalance between the stringent compliance requirements and the capacity of organizations to comply.

As is the case in for–profit enterprise, unreasonable rules and burdensome requirements lead to greater informality (De Soto, 2002). Two of these rules, perhaps unique to Mexico, illustrate this point:

• The application process requires a letter of accreditation: The tax authority requires that organizations seeking tax–exempt status obtain a letter from another government ministry stating that the organization does indeed undertake the activities stated in its corporate purpose. There are a series of problems with this rule. For one, many organizations are in the process of being established, so it is premature to certify that they engage in their intended purpose. In addition, many ministries do not have a procedure in place to issue these letters; besides, in some cases the ministry might not look favorably on an organization whose purpose is to promote greater accountability by the ministry, provoking a conflict of interest (Ablanedo et al., 2007: 60–63).

• A five–percent cap on administrative expenses: under current regulations, authorized donees are limited to spending five percent of the donations they receive on administrative expenses. Aside from the challenge of defining with precision what an administrative expense is, very few entities–for–profit or not–for–profit achieve such a scale of efficiency, especially smaller ones (Ablanedo et al., 2007: 73–76).

The general regulatory tendency has been to impose more stringent rules in order to eliminate the possibility of any fraud. For example, the five–percent rule arose from one institution dedicating more of its resources to keeping up its garden than to caring for the children it was intended to serve. Mexico's tax authorities, or the Tax Administration Service (SAT), developed a very blunt, large instrument, rather than addressing a specific infraction.

Such onerous regulations certainly invoke fear on the part of those acting in good faith, but discourage many from pursuing tax–exempt status. But at present the only recourse the authorities have is to strip an organization of its tax–exempt status. As a high–ranking official in the tax authority once stated, "The leitmotif of the regulatory framework [for authorized donees] is, 'We don't trust you'." In a sense, this is the standard relationship between a tax authority and those it oversees. But the issue is how that distrust is expressed.

Soon after the PSCP and its partners presented their book proposing a fiscal agenda for civil society, the administration presented its fiscal reform effort in June 2007. This proposal would have not only eliminated the tax deductibility of donations, but also would have taxed the income of authorized donees, while exempting that of unions, parties, and chambers of commerce (SHCP, 2007). The debate of the fiscal reform also provided a Rorschach test for various actors, based more on their biases and misrepresentations of civil society than reliable data. The centerpiece of the fiscal reform package presented by the administration was the Business Activity Flat Tax, widely referred to in Mexico by its Spanish acronym, CETU. However, despite complaints about this new tax that did not permit donations to be tax deductible, President Calderón stated that social justice must come before charity as a cardinal virtue and that philanthropic actions were not sufficient to meet the challenge of reducing poverty and inequality in Mexico. Similarly, a few months earlier Carlos Slim, the richest man in Mexico and perhaps the world, made a similar assertion, saying, "Our concept is more to accomplish and solve things, rather than giving; that is, not going around like Santa Claus....Poverty isn't solved with donations" (Layton, 2007b). While this tax proposal came from a right–wing party in government (the National Action Party, or PAN), the left–wing opposition party in Congress (the Party of the Democratic Revolution, or PRD) also mentioned civil society and philanthropy, characterizing it primarily as a realm of fiscal fraud (PRD, 2007).

The PCSP played a leading role in the subsequent effort to amend the administration's proposals and succeeded in maintaining tax exemption for authorized donees as well as the deductibility of donations. However, Congress imposed a seven–percent limitation on deductibility of donations for businesses and individuals, and required the SAT to propose mechanisms for greater transparency of authorized donees (USIG, 2008; Layton, 2007a). In terms of the seven–percent restriction, in general this is not an impediment for most businesses: in an informal analysis of giving among firms that trade on the stock market, the maximum level of donating was between one and two percent of income. In some cases, however, this represents a significant challenge. For example, due to uncertainty over the ability of authorized donees to bill clients for consulting, some organizations have created a separate, for–profit entity for this activity, which in turns donates its earnings to its parent. These organizations are now presented with yet another fiscal complication.

Since the reform, the PSCP has been part of a working group with the Finance Ministry to promote further reforms. A principal area of work has been a discussion of how the SAT can comply with the congressional requirement to promote transparency. The SAT's proposal is to devote a portal on their web site where organizations can post the required information, principally related to their compliance. This is seen as a first, important step toward establishing a system for greater accountability.

The second major area of work has been the expansion of activities eligible for tax–exempt status. At present the Law to Encourage CSO Activities has a more expansive list of activities, including civic education and gender equity. At the end of May the SAT released its Fiscal Miscellany, a set of internal regulations decreed internally, without the need for legislative approval. The Miscellany included this expansion, now clearing the way for more organizations to attain this status.

What we have in Mexico is a fiscal framework in transition, moving –albeit slowly– from a highly restrictive, onerous and exclusionary set of requirements to one that is more enabling. Will all the various improvements to the fiscal framework, in themselves, result in a strong enabling environment for civil society and philanthropy?

Taken alone it is clear that they will not (Irarrázaval and Guzmán, 2005). Nevertheless, they play two critical roles: first, in promoting –or inhibiting– the formality of organizations and their internal capacity, and second, in promoting greater transparency and making enhanced accountability possible.

ACCOUNTABILITY SYSTEM

Accountability, or rendición de cuentas, is a relatively new concept in Mexico, whether one is discussing the government, the private sector, or the third sector. It is clearly one of the "hottest topics to accompany the rise of civil society" (Jordan, 2005: 5). With increased visibility and influence has come greater scrutiny, and this is also true in the Mexican context.

As in the preceding discussions of the legal and fiscal frameworks, a number of governmental and semiautonomous actors are regulators, such as Indesol, the SAT, JAPs, etc. But in all cases the relationship is primarily vertical and closed (i.e. the organization files periodic reports to a regulator regarding its compliance), not a more generalized form of accountability that takes into account an expansive number of stakeholders (Keith Brown, 2005; Layton, 2005). Now in the case of federal funds, and soon in the case of tax exemption, organizations have or will have some or all of their financial information made available via the Internet.

Many organizations have resisted the idea of public reporting requirements for a number of reasons. First, many work in fields that have difficult political contexts, and fear that local caciques or political bosses will use the information against them. In part this fear is a holdover from the 1980s and 1990s, when pro–democracy groups received donations exclusively from abroad and their very legitimacy was challenged by the government and government–sponsored press. Since organizations continue to be subject to intimidation and threats, this fear still has a firm basis in reality. Second, many do not wish to divulge their sources of funds in light of the intense competition for financing. Third, in many cases the organizations simply "don't get it." As not–for–profits engaged in altruistic endeavors, they feel that their purpose alone justifies their relatively privileged status and do not see the need for any further disclosure or mechanisms for accountability. Fourth, the very complex and unreasonable compliance requirements themselves, especially in terms of the fiscal framework, invoke a sense of uncertainty –if not anxiety– on the part of many organizations that fear that they might not comply completely with all the rules: the five–percent limit on administrative expenses is the single most important example. This anxiety is a deterrent for many to embrace greater transparency or an expanded notion of accountability.

In recent years that has been an important debate on this issue, in which the main participants have been academics (Hernández Baqueiro, comp., 2006; Monsiváis, comps., 2005) and civil society organizations concerned with issues of governmental accountability (e.g. Fundar) or NGO–capacity building (Alternativas y Capacidades, A.C.). Perhaps the two most ambitious efforts to build CSO capacity and move in this direction are the Mexican Center for Philanthropy (Centro Mexicano para la Filantropía, Cemefi) Institutionality Index and Fundación Merced's Fortaleza program.5 These programs aim as much or more at the issue of professionalization, but also emphasize key aspects of strengthening accountability. A third effort underway at the state level is an adaptation of the Fundación Lealtad model for Chihuahua.

Again we have for this indicator promising –if incipient– efforts to move Mexico toward a stronger enabling environment.

INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY

The major challenge facing us in this section is how to provide an adequate measurement to answer the question of how an individual organization or sector can demonstrate its institutional capacity. The most direct answer would be to look at the impact the sector has in terms of social, political, or economic development. But in Mexico, as in most countries, there is no systematic data about outcomes or the impact of the sector. Indeed Peter Frumkin (2008) has asked, only slightly rhetorically, if the search for accurate impact, termed the search for accurate performance measurement, is not an "impossible dream." This is perhaps the single most important challenge for the third sector globally, on many fronts.

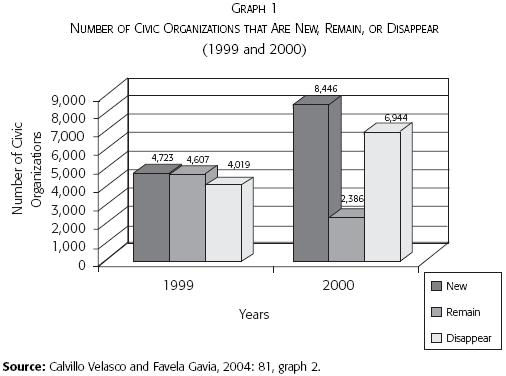

If the most meaningful measurement is not available, then what about a second best? Overall size is a rough measure of capacity. On the face of it, more and perhaps bigger organizations would have a greater capacity to undertake activities. As discussed above, according to Johns Hopkins University (JHU) data Mexico has a relatively small formal sector, and governmental registries confirm this finding. To add a wrinkle here, not only the existence of an organization but its survival from year to year is another way of getting at institutional capacity. Here, data from the Center for Civic Organization Documentation and Research (Cedioc) (Calvillo Velasco and Favela Gavia, 2004) show that even if the overall number of organizations in Mexico might grow from one year to the next, it is not clear how many of these are new and how many are "out of business": this speaks to a lack of institutional capacity to survive, in that nearly half of organizations do not have the ability to maintain their operation from one year to the next. This kind of turnover clearly undermines organizations' impact.

Access to training is another indicator: this seems very limited at this time. While the governmental agency Indesol has offered a free training seminar around the country, only a handful of universities have seminars or master's degree programs in the field (for a more thorough discussion of this issue, see Tapia Álvarez and Robles Aguilar, 2006).

AVAILABILITY OF RESOURCES

Amidst all that is new in calls for greater corporate social responsibility, the awakening of civil society, and increase philanthropy in Mexico and Latin America, it is important to recognize that there is a great continuity as well, not only from strong Catholic traditions of mutual self–help, alms–giving and organizing and leadership development, but also from pre–Hispanic traditions of community service (Sanborn, 2005; Forment, 2003; Bonfil Batalla, 2005).

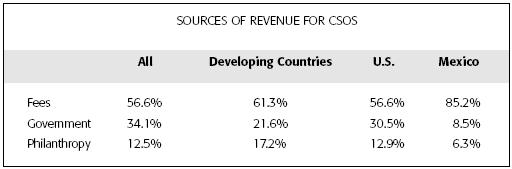

The figures from JHU, although now dated, portray a sector that receives little governmental support (even compared with other Latin American countries), has little philanthropy (one of the lowest percentages of GDP), and is heavily dependent upon fees for services and alternative forms of fundraising: this underscores the points made above in the sections on the legal and fiscal frameworks. Giving (including corporations, individuals, and foundations) as a percentage of GDP is 0.04 percent in Mexico, tying it with the Philippines for last place in a 35–country sample. Contrast that level with the U.S. (1.01 percent), Spain (0.97 percent), or its Latin American neighbors, Colombia (0.32 percent, and Brazil (0.17 percent).

This section examines primarily institutional sources of support, including: Mexican donor institutions, support from U.S. foundations, government support, and remittances. (For lack of recent data on income from fee–for–service work, we will leave this discussion aside for now.)

Mexico's Domestic Donor Institutions

We have systematized data from the only recent directory of donor institutions in Mexico, compiled by Cemefi in 2005, and public sources of information (mainly web sites and news coverage) to develop a portrait of donor institutions in Mexico. It is important to note that the same sort of hard–and–fast separation between organizations that operate programs and grant–making foundations that occurs in the U.S. does not apply in Mexico or in Latin American generally (Letts, 2005: 392–393; Turitz and Zinder, 2005, 266–267). In addition, very few provide financial data on either their endowments (if they have one), or their level of grant–making. Only 21 of the 112 foundations listed, less than 20 percent, provide information on their endowments. In the case of their level of grant–making, a little over a third provides this information (42 of 112). This is consistent with the work of Turitz and Zinder (2005: 274), who found that donor institutions not only in Mexico but also in Brazil and Ecuador tend to operate with a low–profile and often with little transparency.

The paucity of family or individually founded donor institutions in Mexico reflects a broader phenomenon in the region: "Individuals in Latin America exist in different social, cultural and regulatory environments that do not encourage the same kind of foundation formation" (Letts, 2005: 389). As previously mentioned one of the key factors that has promoted the creation of large family foundations in the U.S. is the estate tax, which does not exist in Mexico. The strength of this incentive lies not only in the threat of taxation but also in the social expectation it creates among the peers of the wealthy and the general public.

Family foundations, especially those established by bequests, are rare. This type of foundation is intimately linked to the preferences and habits of the wealthy or high net–worth individuals. The Merrill Lynch and Capgemini 2007 World Wealth Report documents the relatively low level of philanthropic giving in Latin America, and Mexico is no exception:

North Americans gave 7.6% of their portfolios, more than a 20% increase from 2005 levels (largely attributed to a heightened sense of social responsibility among North American HNWIs), while HNWI philanthropists in Asia–Pacific and the Middle East devoted approximately 11.8% and 7.7%, respectively, to philanthropic giving. In Europe, HNW philanthropists allocated 4.6% of their wealth to charitable donations. In Latin America, contributions were approximately 3%. (2008: 21)

The high–profile donations of Carlos Slim, now the second wealthiest individual in the world, may begin to set the bar higher in terms of this type of philanthropy. It is also important to recognize an essential contradiction between the increasing concentration of wealth in Latin America, from which philanthropy emerges: can such efforts, coming from inequality, move their societies toward greater equity and social justice? (De la Maza, 2005: 334–335).6

But there are other models of philanthropic institutions. The community foundation movement is alive in Mexico and is outperforming other Latin American countries, but in many local environments it has not been able to thrive (Letts, 2005: 392). Community foundations have been established in nearly half of Mexico's states, but have often failed to sink strong roots. This U.S. model has been adapted in a number of ways, including more of a tendency toward operating programs and the use of "voluntary" tax contributions in the cases of Fechac (in Chihuahua) and Fundemex (nationally).

Corporate philanthropy, however, has emerged as the "largest component of organized philanthropy" (Letts, 2005: 390). This is reflected in the high number of corporate foundations Cemefi identified. At present it is done "a la mexicana", relatively informally, with little in the way of formal applications requirements (half of the companies do not require applicants to be authorized donees) and little in terms of evaluation and follow–up (Carrillo, Layton, and Tapia, 2008).

Support from U.S. Foundations

Somewhat ironically, the best documented, most transparent source of private charitable support is that which comes from U.S. foundations (Merz and Chen, 2005a; see also Marsal, 2005). This support has been relatively stagnant for the last decade, hovering at an annual contribution of between US$30 million and US$40 million. Because of their size, major grants from the Gates Foundation need to be taken into account in order to track the overall tendency: for example, its nearly US$43 million in support for 2007 represents nearly two–thirds of the total support reported for that year. Although a core group of major foundations (Ford, Hewlett, MacArthur, Kellogg, and Packard) provide about 84 percent of all funding annually, corporate foundations (such as Alcoa) are increasingly important.7 What is clear from the data is not only a decline in dollars but a decline in interest from U.S. funders in Mexico. Contrasting with earlier in the decade when 45 foundations made about 250 grants to a year, current support shows about 30 donors making 200 or fewer grants.

Government

A Cemefi review of newly transparent support for organizations from the federal government provides some interesting insights: this data is now available thanks to the previously mentioned transparency provisions in the LFFAOSC. It seems that many organizations were created and registered for the sole purpose of receiving federal funds, and much of this support goes to semi–autonomous institutions that coordinate their activities with the government.

This study found that overall federal support to institutions with the CLUNI registration increased to 1 659 599 255 pesos in 2006, from 1 180 655 600 in 2003, an increase of nearly Mex$500 million, or 40 percent. But beneath this apparently good news lies a troubling trend. This increase is less than the amount of funds that went to government–related institutions (Mex$523 098 544). These entities ("organizaciones paragubernamentales") are not citizens' organizations but have been established by governmental agencies to administer programs. Their funding is more than double that designated by the Ministry of Social Development specifically for CSOs (Mex$272 000 000). Although the number of registered organizations has increased dramatically, the number of organizations receiving funds was nearly halved, to 1,679 from 2,606 (Cemefi, 2007).

Remittances

Another source of philanthropic giving is collective remittances (Merz and Chen, 2005a).8 The amount of money that immigrants send home annually now far exceeds revenue from tourism and at times is larger than foreign direct investment, with oil revenues being the only source of income from abroad that is larger. It is clear that the overwhelming majority of these funds are used for family purposes, and only a small percentage goes to community projects.

In the 1990s, state governments began matching programs to encourage the use of these contributions by Mexican migrants in the U.S., and approximately six years ago the federal government instituted its 3×1 Program, which matches every dollar sent home by immigrants with one from each of the federal, state, and local governments. These funds are generally used for infrastructure projects (such as paving roads, providing running water, and the like). Despite requirements for local participation, most communities do not organize supervisory bodies. Very little of this financing finds its way to civil society organizations. The U.S.–based organization Hispanics in Philanthropy has launched an interesting project focused on making the most of these resources. It is too early to tell if it will succeed. Although the World Bank reports that the value of remittances sent to Mexico more than tripled from US$7 billion in 2000 to about US$25 billion in 2007, not only had the rate of increase leveled off in recent years, but 2008 might have witnessed the first decline due to the growing U.S. economic crisis.

Conclusion

What we find here as well indicates another relatively weak element in the infrastructure for civil society, and again with signs of transformation and strengthening. What is lacking is a closer assessment of individual giving, which I will take up in the following section.

CULTURAL CONTEXT: LESSONS FROM A NATIONAL SURVEY

Now that we have reviewed the five institutional or structural elements identified by Gaberman, and have found each one underdeveloped in Mexico, we now turn our attention to the sixth, newly identified element, that of the cultural context.

The second major argument is that a key element missing from this conceptualization of the enabling environment is the cultural context for philanthropy and civil society. Culture is defined here as "the values, attitudes, beliefs, orientations, and underlying assumptions prevalent among people in a society" (Huntington, 2000: xv). Over the last two decades a number of leading social scientists have revived a Tocquevillean notion of culture to examine issues of economic development and democratization. They include Robert Putnam, Lawrence E. Harrison, Samuel P. Huntington, Francis Fukuyama, and others. Their work has in turn influenced proponents of the concept of the enabling environment for development, which often focuses narrowly on the regulatory environment and formal institutions of a nation, to broaden their conceptualization. These critics argue that in addition to the legal and fiscal framework cultural values or "habits of the heart" –to use Tocqueville's term– play a critical role in organizational success, at times reinforcing and at others undermining formal rules. As Lusthaus et al. observe, "Sometimes cultural considerations are more important than formal legal considerations in creating an effective framework for enforcement mechanisms for rules" (2002: chapter 2). This analysis of the enabling environment for Mexico's third sector will incorporate the element of culture via the results of the first national public opinion poll on giving and volunteering in Mexico, the National Survey on Philanthropy and Civil Society (known by its Spanish acronym, Enafi). Key values and habits undermine attempts to strengthen the enabling environment for civil society and must be taken into account in any effort to understand or change the status quo (see also Layton, 2006; Ablanedo, 2006; Moreno, 2005: Chapter 17; Butcher, ed., 2008; Ablanedo et al., 2008a and 2008b).

This survey's main lesson is that the informal channels of giving both money and time are much more available and present to Mexicans: so the culture of solidarity is expressed via informal structures of giving and participating. This can be demonstrated by the 79 percent who prefer to give money directly to the needy against the 13 percent who do it via proper organizations of the civil society. The single most revealing result was the answer to the questions, "How do you prefer to give?" The option "Directly to a needy person" was favored by an overwhelming 79 percent of the respondents. Only 13 percent preferred to give "to an institution."

Donation amounts reflect this preference for "giving alms" (limosna): 83 percent report giving less than US$5 (Mex$50), 37 percent between US$5 and US$50 (Mex$5–50), and only four percent give more than US$50. (Theses percentages add up to more than 100 because individuals can report more than one donation).

This philanthropic culture is reflected not only in individual attitudes and habits but also (1) in the organizational structure and behavior of civil society and philanthropic institutions, and also (2) in the legal and fiscal framework. Its most important consequence is the low level of institutionality of Mexico's civil society organizations. The Enafi revealed that only one in three Mexicans know that donations to organizations may be deducted from income taxes, and that of those only 14 percent actually reported taking the donation, i.e. five percent of the total population (Ablanedo et al., 2008b: 16 and 38). Given an onerous fiscal framework, and little interest in deductibility on the part of donors, it is not surprising that many organizations' cost–benefit analysis leads them to conclude that informality makes sense.

This is a small illustration of the vicious circle in which the third sector in Mexico is trapped, a circle which limits its formality, growth, and impact. One way to break this circle and transform the enabling environment is via enhanced accountability.

CONCLUSION: TRANSFORMING THE ENABLING ENVIRONMENT VIA GREATER ACCOUNTABILITY

Through the lens of Gaberman's notion of the enabling environment, amended to include the cultural context, we can understand that no single initiative undertaken in isolation can hope to promote the growth of Mexico's third sector. At present these six elements work in tandem to diminish, if not preclude, the success of any isolated reform. At present the largest challenge looming for organized civil society in Mexico is to establish its relevance to the general public, government, and business alike. It can only do so by generating much greater visibility and much higher levels of trust. This in turn can only be firmly grounded in demonstrating its relevance to the resolution of Mexico's most pressing social, political, and economic challenges. Having an impact is the cornerstone of true accountability.

Brown argues that legitimacy and accountability are fundamental to the success of CSOs, as they strive to mobilize resources and influence public policy (2005: 395–396). But it is important to distinguish between these two concepts: "'Accountability' refers to the extent to which an actor can be held to his or her promise to perform some activity or services." And "'legitimacy' refers to perceptions by key stakeholders that the organization's activities and roles are justifiable and appropriate in terms of the values, norms, laws and expectations that prevail in its context" (Brown, 2005: 396). Thus it is important to bear in mind the "relational character of accountability," as the concept implies that organizations are responsible for their actions vis–à–vis key stakeholders (Villar, 2005: 365). Not only must organizations identify these stakeholders, but they must design strategies to engage them as well.

As Frumkin (2008) admonishes, this effort cannot simply focus on "process accountability" (transparency), i.e. "having clearly defined systems in place and sharing information about the work that is done." The true challenge is moving toward "substantive accountability," which is "based on the sharing of evidence of real effectiveness." In the Mexican context, there are a series of obstacles to achieving the latter type of accountability, not the least of which is encouraging and assisting organizations to seek to document and measure their impact (Layton, 2008). Without a thoughtful, persistent effort to understand and adapt these practices to the Mexican context, it is difficult to imagine how the enabling environment for civil society can be transformed.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ablanedo Terrazas, Ireri. 2006. Ciudadanos ausentes: las causas de la falta de desarrollo de la sociedad civil en México, Mexico City, bachelor's thesis in internacional relations at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México. [ Links ]

Ablanedo, Ireri, Laura García Olson, Sergio García and Michael D. Layton. 2007. Definición de una agenda fiscal para el desarrollo de la sociedad civil en México, (Defining a Fiscal Agenda for the Development of Civil Society Organizations in Mexico). Incide Social, Mexico, D.F., available at http://www.agendafiscalsociedadcivil.org/files/afiscal.pdf (Spanish–language version) and http://www.agendafiscalsociedadcivil.org/files/FiscalAgenda.pdf (English–language version). [ Links ]

Ablanedo Terrazas, Ireri, Alejandro Moreno and Michael Layton. 2008a. "Encuesta Nacional sobre Filantropía y Sociedad Civil (ENAFI): capital social en México," Working Document no. 17, Centro de Estudios y Programas Interamericanos (CEPI), Departamento de Estudios Internacionales, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM), at http://interamericanos.itam.mx/. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2008b. "Encuesta Nacional sobre Filantropía y Sociedad Civil (ENAFI): donaciones en México". Working Document no. 18, Centro de Estudios y Programas Interamericanos (CEPI), Departamento de Estudios Internacionales, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM), at http://interamericanos.itam.mx. [ Links ]

Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo. 2005. México profundo: una civilización negada, México, Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Brinkerhoff, Derick W. 2004. "The Enabling Environment for Implementing the Millennium Development Goals: Government Actions to Support NGOs", paper presented at George Washington University Conference "The Role of NGOs in Implementing the Millennium Development Goals," Washington, D.C. May 12–13. [ Links ]

Brown, L. David. 2005. "Building Civil Society Legitimacy and Accountability", in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 285–306. [ Links ]

Butcher, Jacqueline, ed. 2008. México solidario, participación ciudadana y voluntariado, Mexico City, Limusa/ Cemefi. [ Links ]

Calvillo Velasco, Miriam and Alejandro Favela Gavia. 2004. "Dimensiones cuantitativas de las organizaciones civiles en México", in Jorge Cadena Roa, ed., Las organizaciones civiles mexicanas hoy, Mexico City, Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades, UNAM (Colección Alternativas). [ Links ]

Carrillo Collard, Patricia et al. 2006. El fortalecimiento institucional de las OSCs en México, debates, oferta y demanda, Mexico City, Alternativas y Capacidades A.C. [ Links ]

Carrillo Collard, Patricia, Michael D. Layton and Mónica Tapia 2008. "Filantropía Corporativa 'a la mexicana'," Foreign Affairs en Español, vol. 8, no. 2. [ Links ]

CEMEFI. 2007. Recursos públicos federales para apoyar las actividades de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil, Mexico City, Cemefi. [ Links ]

De la Maza, Gonzalo. 2005. "Enabling Environments for Philanthropy and Civil Society: The Chilean Case", in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

De Soto, Hernando. 2002. The Other Path: The Economic Answer to Terrorism, New York, Basic Books. [ Links ]

Encuesta Nacional de Filantropía (ENAFI) [National Survey on Philanthropy]. 2005. Project on Philanthropy and Civil Society, Mexico, ITAM, at http://www.filantropia.itam.mx/. [ Links ]

Forment, Carlos A. 2003. Democracy in Latin America 1760–1900, Volume I of Civic Selfhood and Public Life in Mexico and Peru, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Frumkin, Peter. 2008. "The Impossible Dream?: Accurate Performance Measurement and Meaningful Accountability in Nonprofit Sector," presentation at the conference "Norteamérica y el dilema de la integración: reflexiones y perspectivas sobre el futuro de la región," Mexico City, February 27. [ Links ]

Gaberman, Barry D. 2003. "Building the Global Infrastructure for Philanthropy," Waldemar Nielsen Seminar Series, Georgetown University, April 11. [ Links ]

García Romero, Diana Leticia. 2007. El dilema de un país de ingreso medio alto: México y los flujos de ayuda internacional para el desarrollo, Mexico City, bachelor's thesis in internacional relations at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM). [ Links ]

Grindle, Merilee. 2005. "Strengthening Philanthropy and Civil Society through Policy Reform", in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Heinrich, V. Finn and Catherine Shea. 2007. "Assessing the Legal Environment for Civil Society around the World: An Analysis of Status, Trends, and Challenges," in V. Finn Heinrich and Lorenzo Fioramonti, eds., Civicus Global Survey of the State of Civil Society, vol. 2: Comparative Perspectives, Sterling, Virginia, Kumarian Press. [ Links ]

Hernández Baqueiro, Alberto, comp. 2006. Transparencia, rendición de cuentas y construcción de confianza en la sociedad y el Estado mexicanos, Mexico City, Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información Pública (IFAI) and Centro Mexicano para la Filantropía (Cemefi). [ Links ]

Herzberg, Benjamin. 2008. Monitoring and Evaluation for Business Environment Reform: A Handbook for Practitioners, U.S., International Finance Corporation, World Bank / DFID / GTZ. [ Links ]

Huntington, Samuel P. 2000. "Cultures Count," in Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P. Huntington, eds., Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress, New York, Basic Books. [ Links ]

Irish, Leon E. et al. 2004. Guidelines for Laws Affecting Civic Organizations, 2nd edition, Open Society Institute, New York. [ Links ]

Irarrázaval, Ignacio and Julio Guzmán. 2005. "Too Much or Too Little? The Role of Tax Incentives in Promoting Philanthropy," in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 285–306. [ Links ]

Jordan, Lisa. 2005. "Mechanisms for NGO Accountability", Global Public Policy Institute Research Paper Series No. 3, Berlin. [ Links ]

Keith Brown, Kimberly. 2005. "Autorregulación vs. regulación estatal: escogiendo la lupa," presentation at the Colloquium on Transparency in Civil Society Organizations, IFAI, Mexico City, June 21, 2005. [ Links ]

Lagloire, Renée and David Palmer. 1999. Perspectives on NGO Capacity–Building in Mexico. An Exploratory Study, Los Altos, CA, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation. [ Links ]

Layton, Michael. 2005. "Transparencia en las OSC en el marco fiscal: rendición de cuentas y fortalecimiento del sector," presentation at the Colloquium on Transparency in Civil Society Organizations, IFAI, Mexico City, June 21, 2005. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2006. "¿Cómo se paga el capital social?: Encuesta Nacional sobre Filantropía y Sociedad Civil (ENAFI)", Foreign Affairs en Español, vol. 6, no. 2, abril–junio. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2007a. "El marco fiscal de las OSC y las reformas hacendarias de 2007: lo bueno, lo malo y lo feo," Mexico City, presentation at the Fiscal Framework, Law and Civil Society Workshop, held in the Law Faculty at Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM), December 7. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2007b. "Flat Taxes, Santa Claus, and Charity: The Need to Strengthen Civil Society in Mexico," The International Journal of Not–for–Profit Law, vol. 9, no. 4, at http://www.icnl.org/knowledge/ijnl/vol9iss4/art_1.htm. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2008. "Filantropía y sociedad civil: el reto de la medición del impacto y la búsqueda de la legitimidad" (Philanthropy and Civil Society: The Challenge of Measuring Impact and the Search for Legitimacy"). Presentation at the conference "Norteamérica y el dilema de la integración: reflexiones y perspectivas sobre el futuro de la región", Mexico City, February 27. [ Links ]

Letts, Christine W. 2005. "Organized Philanthropy North and South," in Cynthia Sanborn and Felipe Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Lusthaus, Charles, Marie–Hélène Adrien, Gary Anderson, Fred Carden and George Plinio Montalván. 2002. Organizational Assessment: A Framework for Improving Performance, Washington, D.C., Inter–American Development Bank and International Development Research Centre. [ Links ]

Marsal, Pablo. 2005. ¿Cómo se financian las ONG argentinas? Buenos Aires, Biblos. [ Links ]

Merrill Lynch and Capgemini. 2007. World Wealth Report, available at http://www.ml.com/media/79882.pdf;11/5/2008, accessed November 1, 2008. [ Links ]

Merz, Barbara and Lincoln Chen. 2005a. "Cross–Border Philanthropy and Equity," in Barbara J. Merz, ed., New Patterns for Mexico, Observations on Remittances, Philanthropic Giving, and Equitable Development, Cambridge, MA,. Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

––––––––––. 2005b. "Filantropía transfronteriza y equidad", in Barbara J. Merz, ed., Nuevas Pautas para Mexico: observaciones sobre remesas, donaciones filantrópicas y desarrollo equitativo, Global Equity Initiative, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 211–231. [ Links ]

Monsiváis C., Alejandro, comp. 2005. Políticas de transparencia: ciudadanía y rendición de cuentas, Mexico City, Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información Pública (IFAI) and Centro Mexicano para la Filantropía (Cemefi). [ Links ]

Moreno, Alejandro. 2005. Nuestros valores, los mexicanos en México y en Estados Unidos al inicio del siglo XXI, vol. VI: Los valores de los mexicanos, Mexico City, Banamex. [ Links ]

Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD). 2007. Propuesta de Reforma Fiscal Integral del PRD, available at http://ierd.prd.org.mx/Coy103–104/jt1.htm. [ Links ]

Paz, Octavio. 1985. The Labyrinth of Solitude, the Other Mexico, and Other Essays, Lysander Kemp et al., trans., New York, Grove Weidenfeld. [ Links ]

Salamon, Lester M. and Stefan Toepler. 2000. The Influence of the Legal Environment on the Development of the Nonprofit Sector, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no. 17. [ Links ]

Sanborn, Cynthia. 2005. "Philanthropy in Latin America: Historical Traditions and Current Trends" in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Sanborn, Cynthia and Felipe Portocarrero. 2005. Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard, DRCLAS. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (SHCP). 2007. Paquete de la Reforma Integral de la Hacienda Pública, México, Gobierno Federal, available at http://www.aplicaciones.hacienda.gob.mx/ucs/reformahacendaria/index.html. [ Links ]

SHCP and Presidencia de la República. 2007. "Iniciativa de Ley de la Contribución Empresarial a Tasa Única", Mexico City, SHCP. [ Links ]

Tapia Álvarez, Mónica and Gisela Robles Aguilar. 2006. Retos institucionales del marco legal y financiamiento a las organizaciones de la sociedad civil, Mexico City, Alternativas y Capacidades A.C. [ Links ]

Turitz, Shari and David Zinder. 2005. "Private Resources for Public Ends: Grantmakers in Brazil, Ecuador and Mexico," in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

United States International Grantmaking (USIG). 2008. Country Information–Mexico. Council on Foundations, available at http://www.usig.org/countryinfo/PDF/Mexico.pdf. [ Links ]

Verduzco, Gustavo. 2003. Organizaciones no lucrativas: visión de su trayectoria en México, Mexico City, El Colegio de México, A.C. and Centro Mexicano para la Filantropía. [ Links ]

Villar, Rodrigo. 2005. "Self–regulation and the Legitimacy of Civil Society: Ideas for Action," in Sanborn and Portocarrero, eds., Philanthropy and Social Change in Latin America, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

1 The original research as detailed below includes the first national survey in Mexico on giving, volunteering, and social capital; a two–year consultation with civil society organizations (CSOs) and the International Center of Not–for–profit Law (ICNL) concerning the fiscal and legal framework; and a consultancy with United Way International that included a survey of corporate philanthropy programs.

2 The question of federal funds will be discussed at greater length below in the section "Availability of Resources."

3 The translation on the web site of the governing body for Mexico City (http://www.jap.org.mx/) is Mexico City Private Assistance Board, but, although accurate word for word, this does not quite capture the sense of the word asistencia, which implies traditional social services.

4 A core group of organizations was supported by the Hewlett Foundation to undertake this effort: Incide Social, AC, the International Center for Not–for–profit Law (ICNL), and the ITAM. The other cosponsor of the resulting publication was the Mexican Center for Philanthropy (Cemefi). Details of the process and the recommendations are available in Ablanedo et al., 2007.

5 Cemefi: Indicadores de Institucionalidad y Transparencia, "Con el propósito de impulsar la profesionalización del sector, dar certeza a los donantes y promover la transparencia y la rendición de cuentas, el Cemefi presenta los Indicadores de Institucionalidad y Transparencia para organizaciones de la sociedad civil," http://www.cemefi.org/spanish/content/category/6/132/159/. As of May 2008, 123 organizations had been certified.

Fundación Merced, Programa Fortaleza: Fortalecimiento Institucional: "Programa que apoya el fortalecimiento, liderazgo y profesionalización de organizaciones para incrementar la eficiencia de su operación y mejorar sus procesos internos, con el fin de asegurar su permanencia y aumentar su impacto," http://www.fmerced.org.mx/fortaleza.htm.

6 It is important to note that Andrew Carnegie based his philanthropy and an estate tax in part on the idea that great fortunes must circulate in a society and cannot remain concentrated generation after generation in the hands of a single family.

7 Based on an analysis of data from Foundation Center Online (see appendix, Tables and Charts: U.S. Grants to Mexico, 2002–2008). See also Merz, 2005; García Romero, 2007.

8 For the purposes of this discussion, we will leave aside individual remittances to family members, as they are not intended to be used for community projects.