In ectotherms most physiological mechanisms are affected by temperature, therefore they carefully regulate body temperature (Tb) within a relatively narrow range by using behavioral adjustments (Cowles & Bogert, 1944). Tb data collected in the field form the basis of most thermal biology reports in the literature (Avery, 1982). In contrast, selected body temperatures (Tsel) in laboratory conditions are rarely reported. Tsel, also known as preferred body temperature, represents the range of body temperatures at which an ectothermic animal seeks to maintain itself by behavioral means in order to carry on their normal activities (Brattstrom, 1965a). This temperature is commonly measured in laboratory conditions that provide an array of thermal environments free of physical and biotic constraints (e. g., predation, costs of thermoregulation; Clusella-Trullas, Terblanche, van Wyk, & Spotila, 2007). Tsel had been recorded for a wide range of diurnal lizard families, mostly in Scincidae, Agamidae, Lacertidae, Liolaemidae, and Phrynosomatidae (Clusella-Trullas & Chown, 2014), nonetheless, within this last family the Tsel of horned lizards (genus Phrynosoma) is actually quite rare in the literature (Lara-Reséndiz, Jezkova, Rosen, & Méndez-de la Cruz, 2014).

Horned lizards are one of the most distinctive lizards in North America. Most horned lizards have diets consisting primarily of native ants, dorsoventrally compressed bodies, cranial horns and body fringes, camouflaging coloration and sedentary habits, a constellation of unusual and interrelated traits including "relaxed" thermoregulation (Pianka & Parker, 1975). According to the latest taxonomic revision, this genus comprises 17 species distributed from Canada to Guatemala (Nieto-Montes de Oca, Arenas-Moreno, Beltrán-Sánchez, & Leaché, 2014). Among lizards, this genus has one of the largest altitudinal distributions (-200 to 3,440 m elev.) and 2 groups have evolved viviparity, apparently a characteristic associated with montane habitats (Hodges, 2004). There have been several reports on Tb in the field and critical temperatures in Phrynosoma (Cowles & Bogert, 1944; Heath, 1962; Lemos-Espinal, Smith, & Ballinger, 1997; Pianka & Parker, 1975; Woolrich-Piña, Smith, & Lemos-Espinal, 2012, and others) and various other reports detailing aspects of its thermal ecology (Brattstrom, 1965b; Christian, 1998; Guyer & Linder, 1985; Powell & Russell, 1985; Prieto & Whitford, 1971, and others). Nevertheless Tsel of horned lizards has attracted relatively little study even though it is essential to understanding behavior, natural history, ecophysiology (Huey, 1982; Sherbrooke, 1997; Sherbrooke & Frost, 1989), and responses to the effects of global warming (Sinervo et al., 2010). Therefore, our principal objective was to determine the selected body temperatures of Phrynosoma in a laboratory thermal gradient and to discuss the results with those of other Phrynosomatid lizards.

We conducted fieldwork during 4 years (2010-2013) in 9 localities from Mexico, A) Zumpago de Neri, Guerrero (P. asio and P. taurus; 17°36'11.73" N, 99°31'19.74" W, 1,130-1,400 m elev.) in a deciduous tropical forest; B) Ensenada, Baja California (P. blainvilli; 31°55'14.94" N, 116°36'32.6" W, 235 m elev.) in a chaparral community; C) volcán La Malinche, Tlaxcala (P. orbiculare; 19°14'38.49" N, 97°59'26.48" W, 3,140 m elev.) in a montane woodland and grassland; D) Chilapa de Álvarez, Guerrero (P. sherbrookei; 17°33'10.85" N, 99°16'15.01" W, 2,020 m elev.) in an oak forest with patches of grassland and scrub; E) Zapotitlán de las Salinas, Puebla (P. taurus; 18°19'39.68" N, 97°27'16.17" W, 1,400 m elev.) in a desert scrub with cacti and xerophilous plants; F) Hermosillo, Sonora (P. solare; 28°57'49.82" N, 111°4'1.2" W, 160 m elev.) in a desert scrub habitat, some with large, columnar cacti and small trees; G) Altamirano, Janos, Chihuahua (P. hernandesi; 30°20'58.24" N, 108°29'26.3" W, 1,830 m elev.) in an oak forest with patches of grassland and scrub; H) Samalayuca, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua (P. modestum; 31°28'33.1" N, 106°28'33.6" W, 1,260 m elev.) in sand dunes and semi stabilized dunes; I) Janos, Chihuahua (P. cornutum; 30°49'31.6" N, 108°28'26.6" W, 1,435 m elev.) in grasslands and scrublands.

All animals were captured by hand. Snout-vent length (SVL) was measured to the nearest 0.1 mm, and sex was determined for all individuals. Our data are based only on adult Phrynosoma (Table 1). In the laboratory, the lizards were maintained at 20 °C in plastic containers. Laboratory experiments were conducted one day after capture using a thermal gradient located in a 20 °C controlled-temperature room. The thermal gradient consisted of a wood box 150 cm × 100 cm × 70 cm high divided into 10 lengthwise tracks separated by insulation barriers to prevent behavioral influence of adjacent lizards. The substrate was 2-3 cm of sandy soil. At one end, and at the center of the box, 3 lamps of 100 W hanging at 30 cm to generate a thermal gradient from 20 to 50 °C throughout the tracks. The Tsel of individuals in the thermal gradient was taken manually each hour, using the digital thermometer Fluke model 51-II, according to the activity period observed in the field and previous records for each species. The 25% and 75% quartiles of each species' Tsel range (Tsel25 and Tsel75) were calculated to obtain the lower and upper limits. After laboratory experiments, all lizards were released at the site of capture.

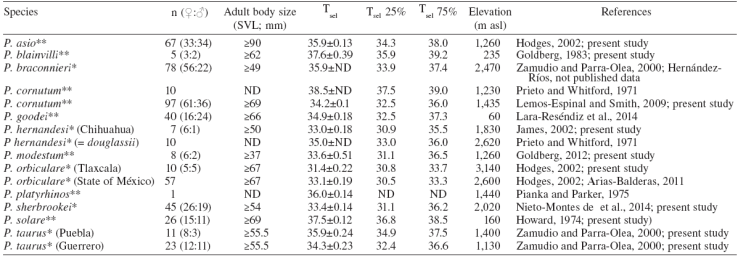

Table 1 Selected body temperature (Tsel) of horned lizards (Phrynosoma) and Tsel range (quartiles 25 and 75%) in °C. Localities description in text. SVL= snout-vent length, ND= not determined. *= Viviparous, **= oviparous.

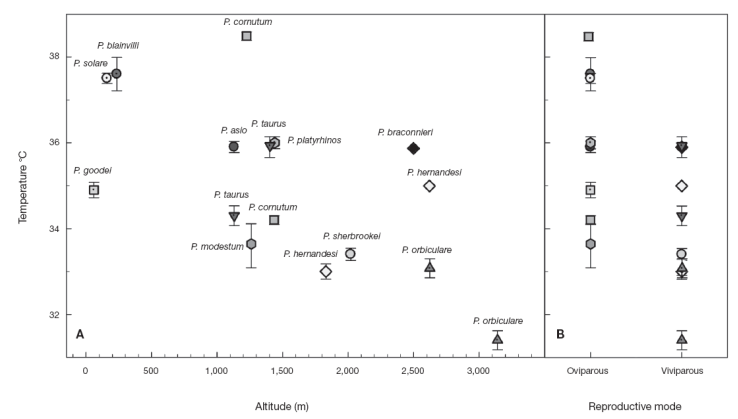

The results in Table 1 show the Tsel average ± standard error (mean±SE) and sample size (n) of each species studied and previous published data. The means of Tsel of the Phrynosoma species reported here are within the range of Tsel observed in other species of Phrynosoma (Table 1). Furthermore, Sinervo et al. (2010) reported an average of Tb of 35.2±0.20 °C for the family Phrynosomatidae considering 210 populations and a Tb range of 26.8-41.5 °C, which is similar to other diurnal lizards (Andrews, 1998). Similarly, Clusella-Trullas and Chown (2014) reported an average of Tsel of 35.1±2.2 °C considering 20 species of phynosomatids. Moreover, Phrynosoma cornutum had the highest Tsel (38.5 °C) and P. orbiculare had the lowest (31.4 °C) (Fig. 1). Tsel of oviparous species varied from 33.5 to 38.5 °C and viviparous species from 31.4 to 35.9 °C (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Mean selected body temperature (Tsel ) of horned lizards (Phrynosoma) as a function of elevation (A) and reproductive mode (B).

Although the Tsel have a genetic basis, in many cases this Tsel of lizards can be altered due to selective pressures of ambient temperatures, as an adaptation to habitat. This means that the Tsel of individuals may be influenced by local environment temperatures (Huey & Bennett, 1987; Sinervo, 1990). Many studies have addressed questions regarding labile or static aspects of lizard's thermal biology (see Clusella-Trullas & Chown, 2014 and references therein). Recently, it has been suggested that Tb and Tsel tend to be similar and conserved within closely related species, even at the level of genus, despite obvious morphological differences, such as size, coloration, reproductive mode or different environmental conditions (Grigg & Buckley, 2013). However, we found that the mean Tsel of horned lizard species seems to be related to the type of habitat, therefore not being overall conserved within the genus Phrynosoma. At localities with higher ambient temperatures horned lizard species tend to have higher average Tsel, while in cooler habitats horned lizard species have lower average Tsel. Again within the genus, higher and lower mean Tsel appear related, respectively, with oviparous and viviparous modes of reproduction (Fig. 1), as noted by Hodges (2004).

Future phylogenetic comparative analysis of thermal preferences of horned lizards should refine issues related to elevation, reproductive mode and other life history traits. In addition, the direction and magnitude of labile shifts in Tsel should be incorporated into mechanistic models (Lara-Reséndiz et al., 2014; Sinervo et al., 2010), to improve predictions of the impact of global climate change on populations of Phrynosoma.

In conclusion, the results presented above suggest that Phrynosoma maintain similar Tsel to other Phrynosomatids and relatively higher Tsel at low elevations than at high elevations. However, this conclusion should be considered preliminary, pending broader data and incorporating biophysical models and phylogenetic analysis on their thermal biology.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)