Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de biodiversidad

versão On-line ISSN 2007-8706versão impressa ISSN 1870-3453

Rev. Mex. Biodiv. vol.85 no.4 México Dez. 2014

https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.44392

Biogeografía

Panbiogeography of the Santa María Amajac area, Hidalgo, Mexico

Panbiogeografía del área de Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo, México

Arturo Palma-Ramírez1, Irene Goyenechea2* and Jesús M. Castillo-Cerón3

1 Léxico Estratigráfico, Servicio Geológico Mexicano. Av. Mariano Jiménez 465, 78280 San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

2 Laboratorio de Sistemática Molecular, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. Ciudad Universitaria, Carretera Pachuca Tulancingo s/n Km. 4.5, 42184 Mineral de la Reforma, Hidalgo, Mexico. * ireneg28@gmail.com

3 Museo de Paleontología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. Ciudad Universitaria, Carretera Pachuca Tulancingo s/n Km. 4.5, 42184 Mineral de la Reforma, Hidalgo, Mexico.

Recibido: 07 febrero 2014

Aceptado: 05 junio 2014

Abstract

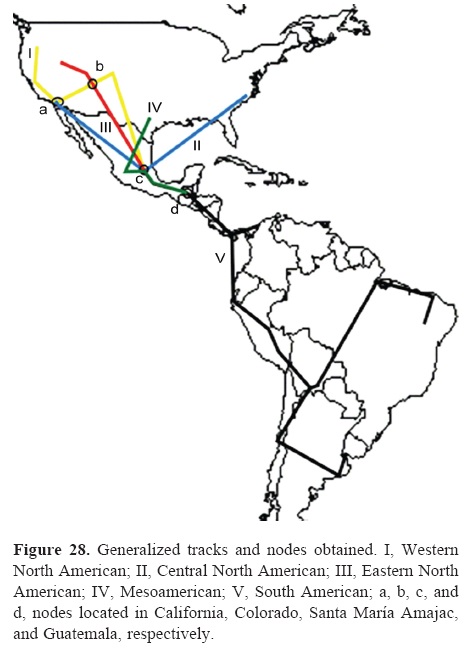

The Santa María Amajac paleolake is located in the central portion of Hidalgo, Mexico. Twenty-seven fossil taxa of aquatic and terrestrial plants, gastropods, ostracods, amphibians, and mammals identified previously in the area of the paleolake were selected and their distribution in America during the Late Pliocene- Pleistocene was analyzed using the panbiogeographic method. As a result of the overlap of 27 individual tracks, 5 generalized tracks were obtained: I) Western North American, II) Central North American, III) Eastern North American, IV) Mesoamerican, and V) South American. The generalized tracks are consistent with previous proposals for extant gymnosperms, amphibians, sauropsids, birds, mammals, aquatic plants, insects, beetles, and nematodes, suggesting that distribution patterns have prevailed since the late Pliocene (Blancan). Four biogeographic nodes were identified, 2 situated in North America, in California and Colorado, the third located in the Santa María Amajac area in central Mexico, and the fourth located in Central America.

Key words: paleolake, track analysis, node, birds, mammals, fossils.

Resumen

El paleolago de Santa María Amajac se ubica en la parte central del estado de Hidalgo, México. Se seleccionaron 27 taxones fósiles pertenecientes a plantas acuáticas y terrestres, gasterópodos, ostrácodos, anfibios y mamíferos que habían sido previamente identificados en el área del paleolago, y se analizó su distribución en América durante el Plioceno Tardío- Pleistoceno a través del método panbiogeográfico. Como resultado de la superposición de los 27 trazos individuales se obtuvieron 5 trazos generalizados: I) norteamericano occidental, II) norteamericano central, III) norteamerciano oriental, IV) mesoamericano y V) sudamericano. Los trazos generalizados coinciden con los propuestos para gimnospermas, anfibios, saurópsidos, aves, mamíferos, plantas acuáticas, insectos, coleópteros y nemátodos recientes; lo que indica que los patrones de distribución han prevalecido desde el Plioceno tardío (Blancano). Se identificaron 4 nodos; 2 localizados en Estados Unidos de Norteamérica, en California y Colorado, otro localizado en el área de Santa María Amajac, en la parte central del país y el último en Centroamérica.

Palabras clave: paleolago, análisis de trazos, nodo, aves, mamíferos, fósiles.

Introduction

Traditionally, panbiogeographic studies have had a neontological approach. The underestimation or exclusion of the fossil record in this research program has been pointed out by different authors (Crisci and Morrone, 1992; Cox and Moore, 1993). Nevertheless, Craw et al. (1999) mentioned that fossils are important in panbiogeography because they could extend the distributional area of taxa, and represent the minimal age of a group, which is not necessarily equivalent to the time of the phylogenetic origin of that group. This contrasts with the traditional dispersalist point of view, where biogeographic hypotheses are based upon the place of first occurrence of a group in the fossil record (Candela and Morrone, 2003). In Mexico, the fossil record is abundant and there are localities ranging from the Precambrian (541 million years ago) to the Holocene (Recent). However, given the geological history of the country and the nature of the fossil record, some periods and environments are represented more frequently than others, and some biological groups are widely documented, while in others the information is scarce or absent (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008). Lacustrine environments are distinct because their biota could be preserved in the fossil record (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008). In Mexico, there is no marine or terrestrial fossil record revealing the total biological richness of a specific place as a reference to understanding current diversity (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008). The Santa María Amajac paleolake is located in the central part of Hidalgo, and the paleofauna has been the subject of several studies. Its fossils include plants, ostracods, gastropods, fishes, amphibians, and mammals, among other groups (Aguilar and Ortiz, 2000; Aguilar et al., 2002; Aguilar-Aguilar and Contreras-Medina, 2003; Martínez-Becerra, 2003; Hernández-López, 2006; Martínez-Martínez and Velasco de León, 2006; Flores-Camargo et al., 2009, Palma-Ramírez, 2012; Zayas-Ocelotl, 2013).

The aim of this study was to determine distributional patterns of different taxa making up the paleobiota in the Santa María Amajac paleolake through a panbiogeographic approach. This work represents the first analysis of its kind in Mexico that uses a significant number of fossil taxa under a panbiogeographical approach. The panbiogeographic method was originally proposed by Leon Croizat (1958) with the statement "Earth and Life evolve together", meaning that there is a correlated history among 3 factors working as one: space, time, and form (Morrone, 2001; Crisci et al., 2003). Panbiogeography emphasizes the spatial or geographical dimension of biodiversity, which allows a better understanding of evolutionary patterns and processes (Craw et al., 1999). Also, it highlights the importance of geographical distribution in maps (Crisci et al., 2003). This method identifies spatial homologies, which indicate the preexistence of ancestral biotas (Grehan, 2001), clarifying the interrelationships between biogeographic areas, and also recognizing transition zones (Ruggiero and Ezcurra, 2003).

Panbiogeography allows the possibility of recognizing whether certain areas have a complex origin (Morrone, 2001), suggesting localities for future cladistic biogeographic analyses (Contreras-Medina and Eliosa-León, 2001). Additionally, this method is especially useful in paleontology, where phylogenetic data of most of the groups is dubious or even incomplete (Gallo et al., 2013).

Materials and methods

An exhaustive search for fossil distributional records in America from the taxa identified in the area of Santa María Amajac was conducted. The data analyzed corresponded to the ages determined according to the chronology based on the presence of North American land mammals (NALMA), proposed by different authors (Castillo-Cerón et al., 1996; Carranza-Castañeda, 2006; Palma-Ramírez, 2012): Blancan (Late Pliocene), Irvingtonian (Late Pliocene- Early Pleistocene), and Rancholabrean (Late Pleistocene). Geographic distributions were obtained from the literature (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980; Carranza-Castañeda, 1991; Castillo-Cerón et al., 1996; Edmund, 1996), and supplemented by the available records of online databases of several scientific institutions, as well as the website: The Paleobiology Database (http://www.paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl). Taxa were used at the taxonomic level of genus, as in many cases a specific identification was not possible. If fossils were considered at the specific level, the number of records gathered would diminish considerably.

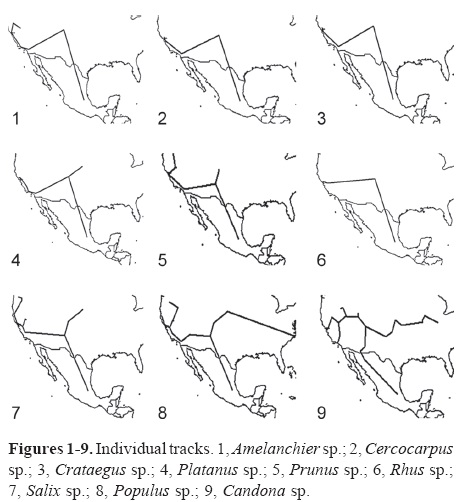

Track analysis. Panbiogeography involves 3 principal concepts: individual track, generalized or standard track, and node (Crisci et al., 2003). An individual track represents the spatial coordinates of a species or group of related species in space (Liria, 1999; Crisci et al., 2003). Operationally, individual tracks are line graphs drawn on a map of connected localities or distributional areas, according to geographical proximity (Crisci et al., 2003). Spatially congruent individual tracks of unrelated taxa constitute a generalized track, which provides a spatial criterion for biogeographic homology (Morrone and Crisci, 1995), and suggest shared histories within biotas (Torres-Miranda and Luna-Vega, 2006). When 2 or more generalized tracks converge or overlap in an area, a biogeographic node is identified. A node is considered a complex area. This means that different ancestral biotic and geologic fragments interrelate in space-time, as a consequence of terrane collision, docking, or suturing (Morrone and Crisci, 1995). Nodes are dynamic biogeographic boundaries where remnant fragments of different ancestral biotas came into contact (Crisci et al., 2003). In this work, we constructed individual tracks for those taxa distributed in the Amajac paleolake (Table 1): 12 plants (11 terrestrial and 1 aquatic), 3 ostracods, 1 gastropod, 2 amphibians, and 9 mammals. Individual tracks were obtained by plotting localities of each taxon on present-day American continent maps, employing ArcView 3.3 software (ESRI, 2002), and connecting them by minimum spanning trees using the Trazos2004 extension (Rojas-Parra, 2004). Generalized tracks and biogeographic nodes were drawn by hand. Due to the scale used in this research, individual tracks were not oriented, as has been done in other panbiogeographic studies (Morrone, 2004, 2009). Generalized tracks were obtained by superimposing the 27 individual tracks for each genus that correspond to the 27 genera included. Generalized tracks were outlined where 2 or more individual tracks overlap (Croizat, 1958; Grehan, 2001; Morrone, 2004; Torres-Miranda and Luna-Vega, 2006). Once the generalized tracks were delimited, nodes were identified in places where 2 or more of these tracks converged.

Results

We constructed 27 individual tracks for the analyzed taxa (Figures 1-27) (2-9, 10-18, 19-27). Overlapping of individual tracks allowed the identification of 5 generalized tracks and 4 nodes (Figure 28). Four of the generalized tracks are located in northern Mexico and northern and central North America. The fifth generalized track extends from southern Mexico to Central America, and southwestern South America. We list the taxa that support the 5 generalized tracks in table 2. The Western North American generalized track (track I) extends from the northwestern United States to California, where it overlaps with one of the edges of the Central North American generalized track (track II); where the Western North American generalized track turns to Colorado, it reaches Mexico through the Sierra Madre Oriental, and reaches the east-central portion of the Mexican Transvolcanic Belt (MTB), where it overlaps with generalized tracks II, III, and IV. Both edges of the generalized track II overlie the generalized tracks I, III, and IV in the east-central portion of the MTB. One branch of the generalized track II, extends from southern California, and passes through the west coast of Mexico, while the other edge descends from the northeastern United States across the Gulf of Mexico. The Eastern North American generalized track (track III) comes from the central part of the United States, where it overlies one of the branches of the generalized track I, and reaches the central part of Mexico overlapping with the generalized tracks I, II, and IV. The Mesoamerican generalized track (track IV) extends from the southeastern United States and descends to the west-central portion of the MTB; it moves to the east-central part of the MTB, where it overlaps with generalized tracks I, II, and III. Track IV runs to Central America, where it overlies the eastern edge of the South American generalized track (track V). The latter extends to the Andes, where it bifurcates to the Amazon basin on one side, and to the Andes mountain range on the other. We identified 4 nodes. The first is located in California, United States. The second is situated in the west-central United States, in Colorado. The third is located in the Santa María Amajac area, in Hidalgo, in the east-central MTB. The fourth is situated in Central America, in Guatemala.

Discussion

Four of the 5 generalized tracks retrieved by the analysis (Figure 28) display an east-west distribution pattern that agrees with a previous hypothesis of an Atlantic-Pacific division along the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Corona et al., 2007; Escalante et al., 2007; and León-Paniagua et al., 2007). The fifth generalized track (South American) is the only generalized track that resembles the Great American Biotic Interchange between North and South America during the late Cenozoic, where 2 of the fossil mammals that support the track are Holarctic taxa, while Pampatherium mexicanum is a Neotropical taxon.

The 5 generalized tracks retrieved by the analysis coincide partially with those proposed by Contreras-Medina and Eliosa-León (2001) for the distribution of extant gymnosperms, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and insects. The Western North American generalized track is congruent with the track that Martínez-Martínez (2008) recovered with fossil records of 3 genera of aquatic plants (Nymphaea, Scirpus, and Typha). This track extends from the western United States to the Santa María Amajac area, in western Mexico. The Mesoamerican generalized track has been retrieved before and partially coincides with the Southern Mesoamerican track proposed by Márquez and Morrone (2003) and with the Mesoamerican track proposed by Toledo et al. (2007). The South American generalized track agrees in its Central American portion with the track proposed by Asiain et al. (2010) based on beetles, with the track proposed by Martínez-Martínez (2008) for aquatic plants, and with the track that Escalante et al. (2011) recovered with nematodes and rodents. The latter coincides with the South American generalized track as well, but only as far as Colombia.

One of the nodes retrieved by the analysis, overlapping tracks III and IV, is located within the Mexican Transition zone proposed by Halffter (1978, 1987) and delimited by Morrone (2006) using the distribution of extant taxa. These authors proposed the Mexican Transition zone as an area where Nearctic and Neotropical elements from the southern United States, Mexico, and Central America overlap. Other authors (Aguayo and Trápaga, 1996; Torres-Miranda and Luna-Vega, 2006) have already recovered nodes in the MTB.

The biogeographic affinity of the Mexican biota has been discussed previously from a paleontological viewpoint by Carranza-Castañeda and Ferrusquía-Villafranca, (1978) and Carranza-Castañeda, (2006), as well as from a neontological perspective (Rzedowski, 1978; Contreras-Medina and Eliosa-León, 2001; Morrone, 2010). The generalized tracks identified in our analysis support the idea of a combined origin of the Mexican biota relating Laurasian and Gondwanan components in the central portion of the country. Mexico's topographic and geographical characteristics have promoted a great variety of ecosystems and one of the highest levels of biodiversity worldwide (Flores-Villela and Gérez, 1989). In the central portion of the country the ecological and geological diversity is shown along with evidence of the integration of different organisms, mainly mammals, from the Nearctic region with immigrants from South America. Tracks obtained with the fossil biota of Santa María Amajac resemble those discovered with extant biotas, suggesting that distribution patterns have prevailed since late Pliocene (Blancan), because Mexico's geological configuration experienced minimal changes in the last 2 million years, and those changes shown in the central portion of the country are due to climatic variations more than geological modifications (Kurtén and Anderson, 1980).

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the Paleontology Lab at the UAEH where this research was done. APR acknowledges Conacyt for the scholarship number 229929. We thank referees for their comments, which significantly contributed to improving this publication.

Literature cited

Aguayo, J. E. and R. Trápaga. 1996. Geodinámica de México y minerales del mar. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, D. F. 106 p. [ Links ]

Aguilar, F. and M. E. Ortiz. 2000. Estudio paleoecológico de la flora pliocénica de Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo: Inferencia del paleoclima y de la paleocomunidad. Bachelor's thesis, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F. 79 p. [ Links ]

Aguilar, F., A. Silva-Pineda and M. P. Velasco-de León. 2002. Registro de Equisetum hyemale en el Plioceno de la región de Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo, México. VII Congreso Latinoamericano y II Congreso Colombiano de Botánica. Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Asociación Latinoamericana de Botánica. p. 378. [ Links ]

Aguilar-Aguilar, R. and R. Contreras-Medina. 2003. La distribución de los mamíferos marinos de México: un enfoque panbiogeográfico. In Introducción a la biogeografía en Latinoamérica: teorías, conceptos, métodos y aplicaciones, J. Llorente-Bousquets and J. J. Morrone (eds.). Las Prensas de Ciencias, Facultad de Ciencias. UNAM. México, D. F. p. 213-219. [ Links ]

Arroyo-Cabrales, J., A. L. Carreño, S. Lozano-García and M. Montellano-Ballesteros. 2008. La diversidad en el pasado. In Capital natural de México, vol. I: Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. Conabio. México, D.F. p. 227-262. [ Links ]

Asiain, J., J. Márquez and J. J. Morrone. 2010. Track analysis of the species of Agrodes and Plochionocerus (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 81:177-181. [ Links ]

Candela, A. M. and J. J. Morrone. 2003. Biogeografía de puercoespines neotropicales (Rodentia: Hystricognathi): Integrando datos fósiles y actuales a través de un enfoque panbiogeográfico. Ameghiniana 40:1-19. [ Links ]

Carranza-Castañeda, O. 1991. Faunas de vertebrados fósiles del Terciario tardío del área de San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato. México, D. F. III Congreso Nacional de Paleontología, Sociedad Mexicana de Paleontología, memorias. p. 20. [ Links ]

Carranza-Castañeda, O. 2006. Late Tertiary fossil localities in central México between 19° 23°N. In Advances in late Tertiary Vertebrate Paleontology in Mexico and the Great American biotic interchange, O. Carranza-Castañeda and E. H. Lindsay (eds.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología y Centro de Geociencias, México, D. F. Special Publication 4. p. 45-60. [ Links ]

Carranza-Castañeda, O. and I. Ferrusquía-Villafranca. 1978. Nuevas investigaciones sobre la fauna Rancho El Ocote, Plioceno Medio de Guanajuato, México; informe preliminar. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Geología 2: 163-166. [ Links ]

Castillo-Cerón, J. M., M. A. Cabral-Perdomo and O. Carranza-Castañeda. 1996. Vertebrados fósiles del Estado de Hidalgo. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. Pachuca. 127 p. [ Links ]

Contreras-Medina, R. and H. Eliosa-León. 2001. Una visión panbiogeográfica preliminar de México. In Introducción a la biogeografía en Latinoamérica: teorías, conceptos, métodos y aplicaciones, J. Llorente-Bousquets and J. J. Morrone (eds.). Las Prensas de Ciencias, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Mexico, D. F. p. 197-211. [ Links ]

Corona, A. M., V. H. Toledo and J. J. Morrone. 2007. Does the Trans-mexican Volcanic Belt represent a natural biogeographic unit? An analysis of the distributional patterns of Coleoptera. Journal of Biogeography 34:1008-1015. [ Links ]

Cox, C. B. and P. D. Moore. 1993. Biogeography: an ecological and evolutionary approach. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford. 326 p. [ Links ]

Craw, R. C., J. R. Grehan and M. J. Heads. 1999. Panbiogeography: Tracking the history of life. Oxford University Press. Biogeography series 11. Oxford. 229 p. [ Links ]

Crisci, J. V., L. Katinas and P. Posadas. 2003. Historical biogeography. An introduction. Harvard University Press. Massachusetts. 250 p. [ Links ]

Crisci, J. V. and J. J. Morrone. 1992. Panbiogeografía y biogeografía cladística: Paradigmas actuales de la biogeografía histórica. Ciencias Special Number 6:87-97. [ Links ]

Croizat, L. 1958. Panbiogeography. Vols. 1 and 2. Published by the author. Caracas. [ Links ]

Edmund, A. F. 1996. A review of the Pleistocene giant Armadillos (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Pampatheriide). In Palentology and paleoenvironments of Late Cenozoic mammals: tributes to career of C. S. (Rufus) Churcher, K. M. Stewart and K. L. Seymour (eds.). University of Toronto Press. Toronto. p. 300-321. [ Links ]

Escalante, T., E. A. Martínez-Salazar, J. Falcón-Ordáz, M. Linaje and R. Guerreo. 2011. Análisis panbiogeográfico de Vexillata (Nematoda:Ornithostrongylidae) y sus huéspedes (Mammalia: Rodentia). Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.) 27:25-46. [ Links ]

Escalante, T., G. Rodríguez, N. Cao, M. C. Ebach and J. J. Morrone. 2007. Cladistic biogeographic analysis suggests an early Caribbean diversification in Mexico. Naturwissenschaften 94:561-565. [ Links ]

ESRI, 2002. ArcView GIS ver. 3.3. Environmental Systems Research Institute, New York. [ Links ]

Flores-Camargo, D. G., M. P. Velasco-de León and E. Naranjo-García. 2009. Estudio taxonómico y paleoecológico de moluscos de agua dulce en el Plioceno del Estado de Hidalgo, México. XI Congreso Nacional de Paleontología, Sociedad Mexicana de Paleontología. Querétaro. p. 24. [ Links ]

Flores-Villela, O. and P. Gerez. 1989. Conservación en México: síntesis sobre vertebrados terrestres, vegetación y uso de suelo. Inireb-Conservation International. p. 302. [ Links ]

Gallo, V., L. S. Avilla, R. C. L. Pereira and B. A. Absolon. 2013. Distributional patterns of herbivore megammals during the Late Pleistocene of South America. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 85:533-546. [ Links ]

Grehan, J. R. 2001. Panbiogeografía y la geografía de la vida. In Introducción a la biogeografía en Latinoamérica: teorías, conceptos, métodos y aplicaciones,yd J. Llorente-Bousquets and J. J. Morrone (eds.). Las Prensas de Ciencias, Facultad de Ciencias. UNAM. México, D.F. p. 181-185. [ Links ]

Halffter, G. 1978. Un nuevo patrón de dispersión en la Zona de Transición Mexicana: el mesoamericano de montaña. Folia Entomológica Mexicana 39-40:219-22. [ Links ]

Halffter, G. 1987. Biogeography of the montane entomofauna of Mexico and Central America. Annual Review of Entomology 32:95-114. [ Links ]

Hernández-López, R. 2006. Descripción de la flora fósil de una localidad de Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo. Bachelor's thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. Pachuca. 92 p. [ Links ]

Kurtén, B. and E. Anderson. 1980. Pleistocene Mammals of North America. Columbia University Press. New York. 447 p. [ Links ]

León-Paniagua, L., A. G. Navarro-Sigüenza, B. E. Hernández-Baños and J. C. Morales. 2007. Diversification of the arboreal mice of the genus Habromys (Rodentia: Cricetidae: Neotominae) in the Mesoamerican highlands. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42:653-664. [ Links ]

Liria, J. 2009. Sistemas de información geográfica y análisis espaciales: un método combinado para realizar estudios panbiogeográficos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79:281-284. [ Links ]

Márquez, J. and J. J. Morrone. 2003. Análisis panbiogeográfico de de las especies de Heterolinus y Homalolinus (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae: Xantholinini. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) 90:15-25.

Martínez-Becerra, C. A. 2003. Estudio anatómico de las aletas impares de los Goodeidos fósiles procedentes de Sanctorum (Formación Atotonilco El Grande), Hidalgo. Bachelor's thesis. Facultad de Estudios Superiores de Zaragoza, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F. 37 p. [ Links ]

Martínez-Martínez, P. 2008. Paleobiogeografía y diversidad de tres géneros de plantas acuáticas fósiles (Typha, Scirpus y Nymphaea). Bachelor's thesis. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F. 61 p. [ Links ]

Martínez-Martínez, P. and P. Velasco-de León. 2006. Plantas acuáticas del Plioceno de las localidades de Santa María Amajac y Sanctorum, Hidalgo, México. IX Congreso Latinoamericano de Botánica. Memorias, 18-25 junio, Santo Domingo. 536 p. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2001. Sistemática, biogeografía, evolución: los patrones de la biodiversidad en tiempo-espacio. Las Prensas de Ciencias, Facultad de Ciencias, México, D.F. 124 p. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2004. Panbiogeografía, componentes bióticos y zonas de transición. Revista Brasileira de Entomología 48:149-162. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2006. Biogeographic areas and transition zones of Latin America and the Caribbean islands based on panbiogeographic and cladistic analyses of the entomofauna. Annual Review of Entomology 51:467-491. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2009. Evolutionary biogeography: an integrative approach with case studies. Columbia University Press. New York. 304 p. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2010. Fundamental biogeographic patterns across the Mexican Transition Zone: an evolutionary approach. Ecography 33:355-361. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. and J. V. Crisci. 1995. Historical biogeography: introduction to methods. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26:373-401. [ Links ]

Palma-Ramírez, A. 2012. Estratigrafía, panbiogeografía y paleomagnetismo del área de Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo, México. M. Sc. Thesis. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca. 72 p. [ Links ]

Rojas-Parra, C. A. 2004. Una herramienta automatizada para realizar análisis panbiogeográficos. Biogeografía 1:31-33. [ Links ]

Ruggiero, A. and C. Ezcurra. 2003. Regiones y transiciones biogeográficas: complementariedad de los análisis en biogeografía histórica y ecológica. In Una perspectiva latinoamericana de la biogeografía, J. J. Morrone and J. Llorente (eds.). Facultad de Ciencias. México, D. F. p. 141-154. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 1978. La vegetación de México. Editorial Limusa. Mexico, D. F. 432 p. [ Links ]

Toledo, V. H., A. M. Corona and J. J. Morrone. 2007. Track analysis of the Mexican species of Cerambycidae (Insecta, Coleoptera). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 51:131-137. [ Links ]

Torres-Miranda, A.M. and I. Luna-Vega. 2006. Análisis de trazos para establecer áreas de conservación en la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana. Interciencia 31:849-855. [ Links ]

Zayas-Ocelotl, L. 2013. Interpretación climática de dos localidades fósiles en Santa María Amajac, Hidalgo, con base en la arquitectura foliar. M. Sc. Thesis. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca. 102 p. [ Links ]