Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de biodiversidad

versión On-line ISSN 2007-8706versión impresa ISSN 1870-3453

Rev. Mex. Biodiv. vol.81 no.3 México dic. 2010

Notas científicas

Intestinal helminths of Lutjanus griseus (Perciformes: Lutjanidae) from three environments in Yucatán (Mexico), with a checklist of its parasites in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean region

Helmintos intestinales de Lutjanus griseus (Peciformes: Lutjanidae) recolectados en tres ambientes de Yucatán (México), con una lista de sus parásitos en las regiones del golfo de México y el Caribe

Nelly Argáez–García1, Sergio Guillén–Hernández2 and M. Leopoldina Aguirre–Macedo1*

1 Laboratorio de Parasitología, Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados del IPN, Carretera Antigua a Progreso Km. 6, Cordemex 97310 Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico. *Correspondent: leo@mda.cinvestav.mx

2 Departamento de Biología Marina, Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México.

Recibido: 17 agosto 2009

Aceptado: 06 febrero 2010

Abstract

A survey of intestinal helminth parasites of the gray snapper, Lutjanus griseus, collected at the estuarine coastal lagoon of Celestún and off the coast of the localities of Chelem and Progreso (Yucatán, Mexico) is presented together with a checklist of gray snapper intestinal helminths in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribben region. Twenty helminth species were found at the Yucatán localities. Eigth of these have previously been reported in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean region and 12 are new records for L. griseus, which increases the number of species recorded for gray snapper in the region to 44. Only 8 helminth species were recorded from fishes collected inside the coastal lagoon, while all 20 were found in fishes from offshore. Differences in species composition and infection parameters of each helminth species between both habitats are presented and discussed, together with similarities in species composition of the intestinal helminth fauna of L. griseus from Yucatán with those reported for the same host species in the Atlantic coast of USA, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean regions.

Key words: Caribbean Sea, marine fishes, Mexico, parasites.

Resumen

En este trabajo se presentan los resultados del análisis helmintológico de los tractos digestivos de pargos Lutjanus griseus colectados en la laguna costera de Celestún y en la zona marina frente a las localidades de Chelem y Progreso (Yucatán, México) junto con una lista de los helmintos intestinales registrados para esta especie de hospedero en el golfo de México y la región del Caribe. Veinte especies de helmintos fueron recuperadas en las localidades de Yucatán. Solamente 8 de éstas se han registrado previamente en el golfo de México y el mar Caribe. Doce especies de helmintos son nuevos registros para L. griseus, incrementando así a 44 el número de especies para este hospedero en la región. Solo 8 especies de helmintos se recuperaron de los peces colectados en la laguna costera, mientras que todas las 20 especies se encontraron en peces colectados en la zona marina. Las diferencias en la composición de especies y los parámetros de infección de cada uno de los helmintos intestinales respecto a los peces colectados en los 3 diferentes hábitats son analizadas. Así mismo, se discute la similitud entre la helmintofauna intestinal de L. griseus en Yucatán con la registrada para la región del Atlántico de EUA, el golfo de México y el mar Caribe.

Palabras clave: mar Caribe, peces marinos, México, parásitos.

The gray snapper, Lutjanus griseus (Linnaeus) (Lutjanidae: Perciformes) is found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, and is one of the most important species for commercial fisheries in the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexicano–Cíntora et al., 2007). Due to its high market value and low levels of commercial harvest, this species has been considerate a good candidate for aquaculture and stock enhancement since the 1970s (Riley et al., 2008). If the aquaculture of this species is going to be developed, it will be necessary to know which parasites could increase under high density conditions. Unfortunately, information on the helminth parasite fauna associated with this species in the Southeast of Mexico is limited to taxonomical records and only 4 published studies exist (Salgado–Maldonado, 1979; Lamothe–Argumedo et al., 1997). In addition, there are no records on the infection parameters for the helminth parasites of this fish species in area.

In this paper, we present a survey of helminth species of the digestive tract of L. griseus in specimens collected in Yucatán at the coastal lagoon of Celestún (20°45' to 20°58' N; 90°15' to 90°25' W), a nursery locality, and 2 offshore habitats for adult fish, namely the localities of Chelem (21° 16' 22.72" N 89° 45' 0.53" W) and Progreso (21° 20' 46.44" N 89° 40' 33.06" W) as well a survey of published records of intestinal helminthes of the gray snapper in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Differences in species composition and the infection parameters of the parasite fauna between the coastal lagoon habitat and the 2 offshore habitats in Yucatán are analyzed and discussed, together with similarities in species composition of the intestinal helminth fauna of L. griseus from Yucatán with those reported for the same host species in the Atlantic coast of USA, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean regions.

A total of 114 specimens of L. griseus were examined from April 2000 to August 2001; 68 were collected at the coastal lagoon of Celestún, while 21 and 25 offshore of the localities of Progreso and Chelem, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fish specimens from Celestún lagoon were caught with hook and line, while those from Chelem and Progreso were provided by local fishermen, who caught the fish with hook and line at 22 m depth. Fish were transported on ice to the laboratory immediately after being captured, where they were examined for the presence of intestinal helminths. Before examination, each specimen was weighed (g) and measured (mm). All helminths were studied in fresh, counted in situ and then preserved in 70% ethanol and processed for subsequent identification following conventional helminthological methods (see Vidal–Martínez et al., 2001). Voucher specimens were deposited at the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), Instituto de Biología, UNAM (Mexico City) and at the Colección del Laboratorio de Parasitología (CHCM) CINVESTAV del IPN, Unidad Mérida (Yucatán, Mexico).

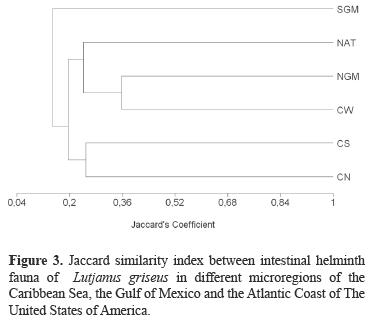

One–way ANOVA was used to test for differences in host length among localities. Prevalence and mean abundance values were calculated for each helminth species at each locality following Bush et al. (1997). Similarity in prevalence and mean abundance values between localities were calculated using the percentage similarity index (Magurran, 2004). Intestinal helminth parasite records from the literature were classified in 7 geographical categories: the Atlantic (AT), with records from Atlantic coast of Florida, Bermudas and Bahamas; the North Gulf of Mexico (NGM), with records from the Gulf of Mexico coast of the Peninsula of Florida to Texas and Tortugas Island; the South Gulf of Mexico (SGM), including Campeche and Yucatán, Mexico; the Caribbean North (CN), records from the Greater Antillas including Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, Dominican Republic and Haiti; Caribbean West (CW) including records from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and the Mexican Caribbean; Caribbean East (CE) all Lesser Antillas and the Caribbean South (CS), including records from Panama, Venezuela and Colombia. Similarity between intestinal helminth fauna of L. griseus reported among regions was calculated using Jaccard similarity index (Magurran, 2004).

Fish lengths from Celestún were significantly smaller on average (133±80 mm) than those from Progreso (346±92 mm) and Chelem (338±71 mm) (F2,93= 171.13; P < 0.05). A total of 20 species of helminths (18 found as adult stages and 2 as larval stages) were collected from the 114 fish specimens examined; of these species, 11 belonged to Trematoda, 4 to Nematoda, 4 to Acanthocephala, and 1 to Cestoda. All 20 species were present in specimens from Progreso, 10 of the 20 were found in Chelem specimens (1 as larval stage) and 8 were found in Celestún (1 as larval stage) (Table 1).

Prevalence, intensity range, and mean abundance values are presented for each helminth species and locality in Table 1. Only 7 of the 20 helminth species were shared between localities, and for most helminth species the highest prevalence values were found for fish caught off Progreso (Table 1). Although fish specimens from Chelem and Celestún shared 80% of their helminth species composition, prevalence and mean abundance values were more similar between helminth species shared by specimens from Progreso and Chelem (Fig. 2).

A total of 32 intestinal helminth species (21 trematodes, 3 cestodes, six nematodes and 2 acanthocephalans) for L. griseus in the North Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea records were recovered from the literature, of which only 5 belong to Mexico (Table 2). Only 1 species (Metadena adglobosa Manter, 1947) has been recorded for all 6 geographical regions (GR), 2 helminth species were present in 5 GR (Hamacreadium mutabile Linton, 1910 and Stephanostomun casum (Linton 1910)), 2 more only in 4 GR (Helicometrina nimia Linton 1910 and Metadena globosa (Linton, 1910)) and all the rest were present in 3 or less GR with 58% of the species being recorded only in just 1 GR each. Overall species similarity between geographical regions was 0.24 ± 0.08. The largest similarity value was found between the helminth fauna of the North Gulf of Mexico and the West Caribbean regions (0.36, Fig. 3).

Prior to this study, 32 helminth species were known to parasitize L. griseus in the Gulf of Mexico and throughout the Caribbean Sea (Table 2). Our data indicate that 12 of the 20 species found at the 3 study sites in Yucatán are new records for L. griseus, increasing the total number of helminth species recorded for this host species to 4. Similar to intestinal helminth communities of other marine fish species from the region, helminth species composition of L. griseus in Yucatán localities is composed mainly of trematodes (11 trematodes, 4 nematodes, 4 acanthocephalans and 1 cestode). For example, 6 of the 11 intestinal parasite species reported for Epinephelus morio by Moravec et al. (1997) were trematodes (in addition to 1 cestode, 3 nematodes, and 1 acanthocephalan), and 6 of the 11 species reported in the gut of Trachinotus carolinus were also trematodes (including also 1 cestode and 4 nematodes) (Sánchez–Ramírez and Vidal–Martínez, 2002). In addition, 6 of 10 intestinal parasite species reported for Cichlasoma urophthalmus at Celestún coastal lagoon were also trematodes (including also 3 cestodes and 1 acanthocephalan) (Salgado–Maldonado and Kennedy, 1997). Such findings agree with an overall pattern of dominance by trematodes in L. griseus as shown by the parasites associated to fish in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbbean sea, since 20 of the 32 helminth species previously recorded were trematodes (Table 2).

Four out of the 7 helminth species shared by the sampled specimens across the 3 localities in Yucatán were specialist trematodes to the fish family Lutjanidae (M. adglobosa, Metadena globosa, Paracryptogonimus neoamericanus and Stephanostomum casum), whereas the remaining 3 helminths are generalist species which can be found in fish species belonging to various families (see Yamaguti, 1971; Amin, 1998)

Presently, the only life cycles for helminth parasites of the gray snapper which have been relatively well described are those of the trematodes M. adglobosa, Hamacreadium gullela and H. mutabile, of which the first species uses Cerithium snails as first intermediate hosts, while H. gullela and H. mutabile use Astraea snails (McCoy 1929, 1930). In addition, Lucania parva and Opsanus beta serve as second intermediate hosts of M. adglobosa. Finally, Cyprinodon variegatus, Gambusia affinis and Poecilia latipinna have been successfully used as experimental second intermediate hosts of M. adglobosa (Schroeder, 1965).

We expected that the total number of helminth species and helminth species composition in gray snappers from Chelem would be similar to that of snappers from Progreso because specimens from these 2 localities were similar in size (Table 1) and were caught in open coastal waters from sites that are relatively close to each other. However, species number and composition were more similar between snapper specimens collected off Chelem and from the Celestún coastal lagoon. Despite this unexpected result, prevalence and abundance values of shared helminth species were more similar between Progreso and Chelem, than between Celestún and Chelem (Figure 2). Although, Schroeder (1965) suggested that the helminth fauna of the gray snapper is replaced by new species after fish leave coastal lagoons, our results show an addition of species for specimens from offshore localities as all the helminth species found in specimens from the coastal lagoon were also present in specimens from Progreso and Chelem. One explanation for this finding is that the offshore specimens sampled had not spent enough time in this habitat to exhibit a replacement of parasite species previously acquired at the coastal lagoon. Given that all parasite species recorded at the coastal lagoon site were also found at the offshore sites, perhaps the most reasonable hypothesis is that the gray snapper specimens sampled offshore are subject to rather slow replacement process of parasite species. On the other hand, it is been reported that as gray snappers increase in size, so do the diversity and volume of items they feed on in coastal lagoons and offshore habitats (Samano–Zapata et al. 1998). This condition may explain the great similarity in prevalence and mean abundance values for parasite species in specimens from Chelem and Progreso, as well as the increase in parasite species richness for specimens from Progreso.

The small values of Jaccard's similarity between the helminth fauna for the 6 geographical regions suggest that there is either a large component of helminth species associated to each particular area, with only a small percentage (11%) corresponding to helminth species widely distributed in the whole region, or that more extensive studies are needed in each region which would permit a more even comparison among regions. For example, most of the records of some geographical regions come from only 1 or 2 articles were only a particular locality was examined in contrast to our data that come from 3 localities and a larger number of fish.

The authors would like to acknowledge Agustin Jiménez Ruiz from Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Virginia León–Règagnon, and Luis García Prieto from the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (Mexico, D.F.) for providing important references; thanks also to Rod Bray (Natural History Museum), David González–Solís (Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Chetumal) and Guillermo Salgado–Maldonado (Instituto de Biología, UNAM) who helped with the identification of the hemiurid trematodes, nematodes and acanthocephalans, respectively. Tomás Scholz and Victor M. Vidal–Matínez provided comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Clara Vivas–Rodriguez and Gregory Arjona from CINVESTAV–IPN provided technical support. This study was funded by CONACyT (grant no. 44590).

Literature cited

Amin, O. 1998. Acanthocephala. Marine flora and fauna of the Eastern United States. NOAA Technical Report NMFS, no. 135. 32 p. [ Links ]

Barreto, A. L, 1922. Revisão da família Cucullanidae Barreto, 1916. (1). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 14: 68–87. [ Links ]

Bosques–Rodríguez, J. L. 2004. Metazoan parasites of Snappers, Lutjanidae (Pisces) from Puerto Rico. Tesis maestría, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Campus Mayagüe. 178 p. [ Links ]

Bush, A. O., K. D. Lafferty, J. M. Lotz and A. W. Shostak 1997. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. Journal of Parasitology 83:575–583. [ Links ]

Cable, R. M. and B. A. Mafarachisi. 1970. Acanthocephala of the genus Gorgorhynchoides parasitic in marine fishes. Indian Veterinary Research Institute H. D. Srivastava Commemorative Volume. p. 255–261. [ Links ]

Dyer, W. G., E. H. Williams Jr. and L. Bunkley–Williams. 1985. Digenetic trematodes of marine fishes of the western and southwestern coast of Puerto Rico. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 52:85–94. [ Links ]

Dyer, W.G., E. H. Williams Jr. and L. Bunkley–Williams. 1992. Homalometron dowgialloi sp. n. (Homalometridae) from Haemulon flavolineatum and additional records of digenetic trematodes of marine fishes in the West Indies. Proceedings of the Helminthlogical Society of Washington 59:182–189. [ Links ]

Dyer, W. G., E. H. Williams Jr. and L. Bunkley–Williams. 1998. Some digenetic trematodes of marine fishes from Puerto Rico. Caribbean Journal of Sciences 34:141–146. [ Links ]

Fischthal, J. H. 1977. Some digenetic trematodes of marine fishes from the barrier reef and reef lagoon of Belize. Zoological Scripta 6:81–88. [ Links ]

González–Nava, M.E. 1994. Helmintos endoparásitos (Trematoda: Digenea) en ocho especies de peces de agua salobre y marina de la laguna de Celestún, Yucatán, México. B. S. Thesis, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Veracruzana,Tuxpam, Veracruz, Mexico. 91 p. [ Links ]

González–Solís, D., N. Argáez–García and S. Guillén–Hernández. 2002. Dichelyne (Dichelyne) bonacii n. sp. (Nematoda: Cucullanidae) from the gray snapper Lutjanus griseus and the black grouper Mycteroperca bonaci of the coast of Yucatán, Mexico. Systematic Parasitology 53:109–113. [ Links ]

González–Solís, D., V. M. Tuz–Paredes and M. A. Quintanal–Loria. 2007. Cucullanus pargi sp. n. (Nematoda: Cucullanidae) from the gray snapper Lutjanus griseus off the southern coast of Quintana Roo. Folia Parasitologica 54:220–224. [ Links ]

Hanson, M. L. 1950. Some digenetic trematodes of marine fishes of Bermuda. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 17:74–89. [ Links ]

Lamothe–Argumedo, R., L. García–Prieto, D. Osorio–Sarabia and G. Pérez–Ponce de León. 1997. Catálogo de la Colección Nacional de Helmintos. Instituto de Biología, UNAM–Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. 211 p. [ Links ]

Linton, E. 1907. Notes on parasites of Bermuda fishes. Proceedings of the Natural Museum 33:85–126. [ Links ]

Linton, E. 1908. Helminth fauna of the Dry Tortugas. I. Cestodes. Publications of the Carnegie Institute of Washington 102:157–190. [ Links ]

Linton, E. 1910. Helminth Fauna of the Dry Tortugas. II Trematodes. Publication of the Carnegie Institute of Washington 133:11–98. [ Links ]

MacCallum, G. A. 1917. Some new forms of parasitic worms. Zoopathology 1:43–75. [ Links ]

Magurran, A. 2004. Measuring Ecological diversity. Blakwell Publishers, London. 256 p. [ Links ]

Manter, H. W. 1947. The digenetic trematodes of marine fish of Tortugas Florida. American Midland Naturalist 38:257–416. [ Links ]

Mexicano–Cíntora, G., C. O. Leonce–Valencia, S. Salas and M. E. Vega–Cendejas. Recursos Pesqueros de Yucatán: Fichas técnicas y referencias bibliográficas. Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN (CINVESTAV) Unidad Mérida. Mérida, Yucatán, México, 150 p. [ Links ]

McCoy, O. R. 1930. Experimental studies on 2 fish trematodes of the genus Hamacreadium (Family Allocreadiidae). Journal of Parasitology 17:1–13. [ Links ]

Moravec, F., V. M. Vidal–Martínez, J. Vargas–Vázquez, C. Vivas–Rodríguez, D. González–Solís, E. Mendoza–Franco, R. Simá–Álvarez and J. Güemez–Ricalde. 1997. Helminth parasites of Epinephelus morio (Pisces: Serranidae) of the Yucatán Peninsula, southeastern Mexico. Folia Parasitologica 44:255–266. [ Links ]

Nahhas, M. F. and R. M. Cable.1964. Digenetic and Aspidogastrid Trematodes from marine fishes of Curaçao and Jamaica. Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 11:167–228. [ Links ]

Overstreet, R. M. 1969. Digenetic trematodes of marine teleost fishes from Biscayne Bay, Florida. Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 15:119–176. [ Links ]

Rees, G. 1970. Some helminth parasites of fishes of Bermuda and an account of the attachment organ of Alcicornis carangis MacCallum, 1917 (Digenea: Bucephalidae). Parasitology 60:195–221. [ Links ]

Riley, K. L., E. J. Chesney and T. R. Tiersch, 2008. Field collection, handling, and refrigerated storage of sperm of red snapper and gray snapper. North American Journal of Aquaculture 70:356–364. [ Links ]

Salgado–Maldonado, G. 1979. Acantocéfalos de peces VI. Hallazgo de Gorgorhynchoides bullocki Cable y Mafarachisi 1970 (Acantocephala: Arhythmacantidae) y descripción de algunos de sus estados juveniles. Anales del Instituto de Biología. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Serie Zoología 50: 35–50. [ Links ]

Salgado–Maldonado G. and C. R. Kennedy. 1997. Richness and similarity of helminth communities in the tropical fish Cichlasoma urophthalmus from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Parasitology 114:581–590. [ Links ]

Samano–Zapata, J. C., M. E. Vega–Cendejas and M. Hernández–De Santillana..1998. Alimentary ecology and trophyc interactions of juveniles "pargo mulato" (Lutjanus griseus Lineaus, 1758) and "rubia" (L. sinagris Lineaus, 1958) from the noroccidental coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute 50:804–826. [ Links ]

Sánchez–Ramírez, C. and V. M. Vidal–Martínez. 2002. Metazoan parasite infracommunities of Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus) from the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Journal Parasitology 88:1087–1094. [ Links ]

Schroeder, R. E. 1965. Ecology of the intestinal trematodes of Gray Snapper, Lutjanus griseus, near Lower Matecumbe Key, Florida, with a description of a new species. In Studies in tropical Oceanography No. 10. Investigations of the Gray Snapper Lutjanus griseus, W. A. Starck (ed.). University of Miami Press. Coral Gables, Florida. p. 168–221. [ Links ]

Siddiqi, A. H., R. M. Cable. 1960. Digenetic Trematodes of marine fishes of Puerto Rico. Scientific Survey of Puerto Rico and the Virgen Islands. New York Academy of Science 17:257–369. [ Links ]

Vélez, I.1987. Sobre la fauna de trematodos en peces marinos de la familia Lutjanidae en el Mar Caribe. Actualidades Biológicas 16:70–84. [ Links ]

Vidal–Martínez, V. M., M. L. Aguirre–Macedo, T. Scholz, D. González–Solís and E. F. Mendoza–Franco. 2001. Atlas of the helminth parasites of cichlid fish of México, Academia, Praha. 165 p. [ Links ]

Williams, E. H. 1983. New host records for some nematode parasites of fishes from Alabama and Adjacent Waters. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 50:178–182. [ Links ]

Zambrano, J. L. F., C. S. Rojas and Y. R. Leon. 2003. Parasites in juveniles of Lutjanus griseus (Pisces: Lutjanidae) at La Restinga Lagoon, Margarita Island, Venezuela. Interciencia 28:463–468. [ Links ]