Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de biodiversidad

On-line version ISSN 2007-8706Print version ISSN 1870-3453

Rev. Mex. Biodiv. vol.81 n.1 México Apr. 2010

Taxonomía y sistemática

Rhinella fernandezae (Anura, Bufonidae) a paratenic host of Centrorhynchus sp. (Acanthocephala, Centrorhynchidae) in Brazil

Rhinella fernandezae (Anura, Bufonidae), hospedero paraténico de Centrorhynchus sp. (Acanthocephala, Centrorhynchidae) en Brasil

Viviane Gularte Tavares dos Santos* and Suzana B. Amato

Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Caixa Postal 15014, 91501–970 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

*Correspondent:

vivi.tavares@pop.com.br

Recibido: 23 enero 2009

Aceptado: 01 junio 2009

Abstract

Cystacanths of Centrorhynchus sp., were found in the coelomic cavity of anurans Rhinella fernandezae (Gallardo, 1957), collected in the municipality of Imbé, on the northern coast of Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil. In a sample totaling 90 anurans, the prevalence of cystacanths was 84%, and the mean intensity of infection was 4.79 helminths/host. This is the first record of Centrorhynchus sp. cystacanths in anurans from Southern Brazil and from the State of Rio Grande do Sul.

Key words: cystacanths, anurans, Southern Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul.

Resumen

Se encontrararon cistacantos de Centrorhynchus sp. en la cavidad celómica del anuro Rhinella fernandezae (Gallardo, 1957), recolectado en el municipio de Imbé, en la costa norte de Rio Grande do Sul en el sur de Brasil. En una muestra de 90 anuros, la prevalencia de cistacantos fue del 84%, y la intensidad media de infección fue del 4.79 helmintos/hospedero. Este es el primer registro de cistacantos de Centrorhynchus sp., en anuros en el sur de Brasil y en el estado de Rio Grande do Sul.

Palabras clave: cistacantos, anuros, sur del Brasil, Rio Grande do Sul.

Introduction

There are about 813 species of anurans described from Brazil, which represents the highest country richness in the world (SBH, 2008). However, studies focusing on the helminthological fauna of these amphibians are rare. The burrowing toad Rhinella fernandezae is found in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (IUCN, 2008). This species usually lives in burrows constructed using its hind legs (Achaval and Olmos, 2003). According to Duré and Kehr (1999), R. fernandezae has a diverse diet that includes insects, arachnids, and crustaceans, but shows a preference for ants.

Adult acanthocephalans parasitize the intestine of vertebrates and utilize arthropods as intermediate hosts, where larval development occurs. Acanthocephalans do not have free–living larval stages, and a paratenic host in the life cycle is present in some species. The paratenic host acts as a trophic bridge between the intermediate and definitive hosts, concentrating and passing the cystacanths to the definitive host.

Materials and methods

A total of 90 specimens of R. fernandezae were collected between August 2006 and April 2007, in the municipality of Imbé (29°58'31"S, 50°07'41"W), on the northern coastal region of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil (license n° 026/2006). Anurans were captured manually using a shovel, and were transferred to the laboratory in plastic containers. Prior to necropsy the animals were maintained alive in the laboratory in a terrarium with substrate from the sampling site. Toads were killed using 2% lidocaine (Geyer®: Di Bernardo, personal communication), a local anesthetic that was spread on the abdomen of each animal and absorbed through the skin. Necropsy procedures, sampling and helminth processing followed Amato et al. (1991). Acanthocephalans were removed from cysts, placed in distilled water, and kept in the refrigerator to permit the proboscis to evert. Subsequently, acanthocephalans were fixed using AFA (ethanol 70° GL – 93 parts; formalin 37%– 5 parts; glacial acetic acid – 2 parts), gently compressed, stained with Delafield's hematoxylin (Humason, 1972), clarified in Faia's creosote, and mounted using Canada balsam. Measurements are presented in micrometers (µm), or as otherwise indicated; amplitude of variation of each character is followed by the mean, standard deviation and the numbers of specimens measured are presented between parentheses. Representative specimens were deposited in the Helminthological Collection of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (CHIOC), Rio de Janeiro, RJ and in the Helminthological Collection of the Zoology Department, UFRGS (CHDZ – UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS. All anurans examined were deposited in the Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (MCT–PUCRS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Description

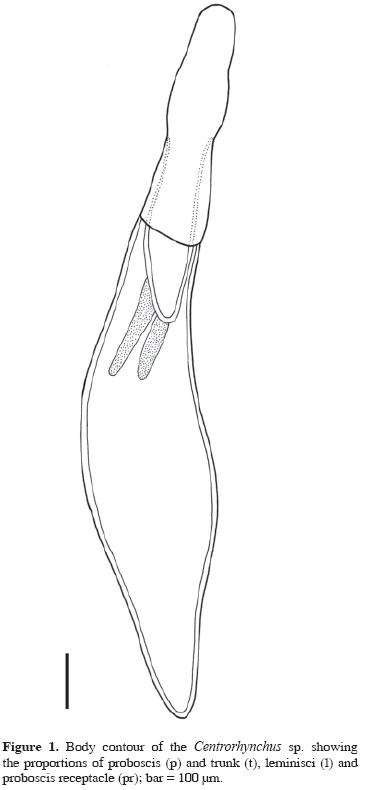

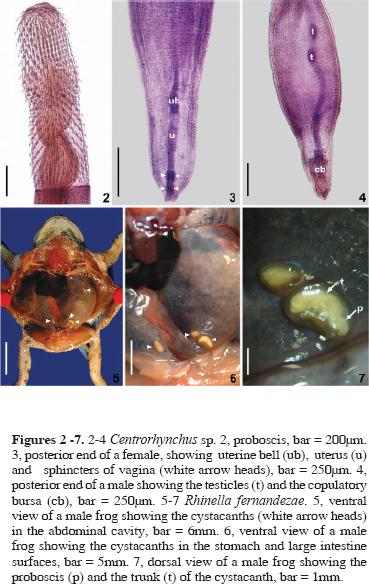

Centrorhynchus sp. (Figs. 1–7)

Based on 15 specimens (10 females and 5 males). Centrorhynchidae.

General: Trunk smooth and cylindrical (Fig.1). Proboscis cylindrical (Figs.1–2) with a constriction at insertion of proboscis receptacle, with 28 to 30 longitudinal rows of 20 to 23 hooks, 8 to 11 rooted hooks and 10 to 13 rootless spines. Apical hooks 40 to 60 (46.96, 14, 5.30) long, rooted hooks 35 to 50 (41.54, 13, 4.39) long, rootless spines length 30 to 42.5 (37.69, 13, 3.46) long. Proboscis receptacle with double wall (Fig.1), length 467.65 to 800 (657.49, 10, 102.44), width 150 to 328.35 (216.03, 10, 54.20). Lemnisci (Fig. 1) extending 200 to 450 (294, 10, 88, 10) beyond posterior end of proboscis receptacle.

Females. Unencysted cystacanths 1.836 to 4.019 mm (2.535, 10, 0.678) long and 474 to 693 (549.77, 10, 77.51) wide. Proboscis length 0.865 to 1.227 mm (1.00, 10, 0.143); width of anterior end 159.20 to 278.60 (195.47, 10, 37.09), width of the inflated portion 189.05 to 398 (261.99, 10, 68.17), width at insertion of receptacle 150 to 348.25 (212.39, 10, 64.08), and width at the base 220 to 388.05 (284.23, 10, 57.83). Lemnisci had a length varying between 490 and 766.15 (636.26, 10, 76.31). Vulva with 4 sphincters; uterus and uterine bell were visible (Fig. 3).

Males. Unencysted cystacanths, 2.613 and 3.762 mm long (3.168, 5, 0.490) and 455.40 to 633.60 (542.52, 5, 66.56) wide. Proboscis length 0.885 to 1.346 (1.036, 5, 0.188); width at the anterior end 137.5 to 200 (166, 5, 27.31), a width at the inflated portion 210 to 315 (263.57, 4, 51.54), width at insertion of receptacle 142.5 to 275 (209.38, 4, 57.82), and width at base 230 to 357.5 (295, 4, 57.12). Lemnisci 567.15 and 796 (713.08, 3, 312.34) long. Two testes (Fig. 4), 95 to 150 (121.25, 5, 19.93) long.

Taxonomic summary

Host: Rhinella fernandezae (Gallardo, 1957)

Infection site: coelomic cavity.

Collection site: municipality of Imbé, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Prevalence: 84%

Mean intensity of infection: 4.79 helminths/host

Mean abundance of infection: 4.04 helminths/host

Amplitude of intensity of infection: 1–36 helminths/host

Specimens deposited: CHIOC 37201, CHIOC 37202; CHDZ JFA 2481–2–1, CHDZ JFA 2476–5–1.

Remarks

Helminths found encysted (Figs. 5–7) in the coelomic cavity were identified as cystacanths of Centrorhynchus Lühe, 1911, according to the key of Petrochenko (1971). The proboscis of the cystacanths was typical for the genus, divided into 3 regions, the middle one inflated, and a constriction at the insertion of the proboscis receptacle (Figs. 1–2).

At present, Centrorhynchus encompasses at least 84 described species. The majority of these are found as adults in birds (Falconiformes and Strigiformes), and rarely in mammals (Amin, 1985). Travassos (1926) listed 4 species for the Brazil C. tumidulus (Rudolphi, 1819), C. opimus Travassos, 1919, later transferred to Sphaerirostris, C. giganteus Travassos, 1921, and C. polymorphus Travassos, 1925, and suggested that amphibians and reptiles could act as paratenic hosts. Schmidt (1985) reported an orthopteran (Acridoidea) as intermediate host of species in this genus.

Comparison between the proboscises of the 3 species of Centrorhynchus found in Brazil and our material showed differences in the numbers of hook and spine rows, number of hooks, number of spines, and proboscis size (Table 1). The onchotaxis of the cystacanths collected in R. fernandezae most closely resembles to those of the cystacanths of Centrorhynchus sp. of A. floridana; however, the proboscis size in specimens from anuran hosts is twice larger. Based on these criteria, identification of our Centrorhynchus larvae is pending experimental infections of avian hosts to obtain the adult forms.

Amato et al. (2003) published the first record of pigment dystrophy in terrestrial isopods, Atlantoscia floridana (van Name), caused by the presence of cystacanths of Centrorhynchus sp., the first record Centrorhynchus in a terrestrial isopod. Rodrigues (1970) found cystacanths of Centrorhynchus sp. in Hemidactylus mabouia (Moreau de Jonnès, 1818), in the city of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, while De Fabio (1982) recorded cystacanths in 6 species of leptodactylideans in a rural area of Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Puga and Torres (1996) found cystacanths in the coelomic cavity of Eupsophus sp. in Chile. Smales (2007), was the first author to reported R. fernandezae as a paratenic host of Centrorhynchus spp. in a work done with specimens from Paraguay.

The presence of cystacanths of Centrorhynchus in paratenic hosts is the result of the ingestion of arthropods (intermediate hosts), terrestrial isopods (Amato et al. 2003), and coleopterans (Hamann et al. 2006).

Smales (2007) reported lower prevalence and mean intensity (8.3% and 1 helminth/host, respectively) than those observed for R. fernandezae collected in Imbé, RS, (84% and 4.79 helminths/host, respectively). The high prevalence found in the present study represents a noteworthy contribution for the knowledge of the biology of Centrorhynchus, and may indicate a different relationship between the parasite and its host than that reported by Smales (2007).

Rhinella fernandezae is reported for the first time as a paratenic host of a species of Centrorhynchus in Brazil. This is also the first record of cystacanths in anurans from southern Brazil and in the State of Rio Grande do Sul.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the curator of MCT–PUCRS, Dr. Gláucia Pontes. Professor Dr. Marcos Di Bernardo (in memoriam) offered valuable comments on the identification of the host and Professor Dr. José Felipe R. Amato provided pictures of the host. Samantha Seixas and Eliane Fraga helped in the laboratory. Collection of the hosts was made possible by a license from IBAMA and CNPq provided a scholarship for the first author.

Literature cited

Achaval, F. and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfíbios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo. Graphis Impresora, 2a ed., 136p. [ Links ]

Amato, J. F. R; S. B. Amato; P. B. Araújo and A. F. Quadros. 2003. First report of pigmentation dystrophy in terrestrial isopods, Atlantoscia floridana (van Name) (Isopoda, Oniscidea) induced by larval acanthocephalans. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 20:711–716. [ Links ]

Amin, O. M. 1985. Classification, In Biology of the Acanthocephala, D. W. T. Crompton and B. B. Nickol (eds.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, XI+ p.27–72. [ Links ]

De Fabio, S. P. 1982. Helmintos de populações simpátricas de algumas espécies de anfíbios anuros da Família Leptodactylidae. Arquivos da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro 5:69–83. [ Links ]

Duré, M. E and A. I. Kehr. 1999. Explotación diferencial de los recursos tróficos en cuatro espécies de bufonidos del Nordeste Argentino. Actas Ciencia & Técnica 6:17–20. [ Links ]

Hamann, M. I., C. E. González and A. I. Kehr. 2006. Helminth community structure of the oven frog Leptodactylus latinasus (Anura, Leptodactylidae) from Corrientes, Argentina. Acta Parasitologica 51:294–299. [ Links ]

Humason, G. L. 1972. Animal tissue techniques. São Francisco, W.H. Freeman and Company, 641p. [ Links ]

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL and NATURE SERVE, 2008. Global Amphibian Assessment. Available at: http://www.globalamphibians.org. (Accessed in 05.2008). [ Links ]

Kwet, A. and M. Di–Bernardo. 1999. Pró–Mata – Anfíbios. EDIPUCRS, Porto Alegre. 107p. [ Links ]

Petrochenko, V. I. 1971. Acanthocephala of domestic and wild animals. Vol. 1 Keter Press, Jerusalem. 465p. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, H. O. 1970. Estudo da fauna helmintológica de "Hemidactylus mabouia" (M. de J.) no Estado da Guanabara. Atas da Sociedade de Biologia do Rio de Janeiro 12 (supl.):15–23. [ Links ]

SBH (Sociedade Brasileira de Herpetologia). 2008. Brazilian amphibians – List of species. . Available at: http://www.sbherpetologia.org.br. [Accessed in 06.2008]. [ Links ]

Schmidt, G. D. 1985. Development and life cycles. In Biology of the Acanthocephala, D. W. T. Crompton and B. B. Nickol (eds.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, XI+p. 273–305. [ Links ]

Smales, L. R. 2007. Acanthocephala in amphibians (Anura) and reptiles (Squamata) from Brazil and Paraguay with description of a new species. Journal of Parasitology 93:392–398. [ Links ]

Travassos, L 1926. Contribuições para o conhecimento da fauna helminthologica brazileira XX. Revisão dos Acanthocephalos brasileiros. Parte II. Família Echinorhynchidae Hamann, 1892, sub.–fam. Centrorhynchinae Travassos, 1919. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 19: 31–125. [ Links ]