Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista odontológica mexicana

Print version ISSN 1870-199X

Rev. Odont. Mex vol.21 n.3 Ciudad de México Jul./Sep. 2017

Original works

Comparison of Nolla, Demirjian and Moorrees methods for dental age calculation for forensic purposes

1 Forensics Dentistry Area, Research Institutes, School of Dentistry, University of Zulia, Maracaibo, Zulia State, Venezuela.

Objective:

The purpose of the present study was to compare three methods for calculation of dental age (DA) to be used for forensic purposes.

Material and methods:

512 panoramic X-rays of subjects of both genders living in Maracaibo, State of Zulia, Venezuela were selected (272 females, 240 males). Selected subjects were in the 6-18 years chronological age (CA) range. Maturation stages of Nolla, Moorrees et al and Demirjian et al were assigned to seven permanent teeth of the left side, and DA was calculated according to methodology of each author. CA was obtained where different stages of maturation were observed, as well as mean difference between DA and CA as calculated with each method were obtained with a t student test for related samples.

Results:

In general, females reached maturation stages at earlier ages than males. The total sample revealed age over-estimation for the Demirjian method (-0.14 ± 1.45), whereas, a sub-calculation was observed for the Nolla and Moorrees et al method. This under-estimation was greater for the Moorrees at al method (2.63 ± 2.09) when compared to Nolla method (0.42 ± 1.38) and differences between DA and CA were found to be statistically significant.

Conclusion:

In the total studied sample, it was determined that Demirjian et al method was the most accurate.

Key words: Dental development; dental age; Nolla method; Moorrees method; Demirjian method

Objetivo:

El propósito de este estudio fue comparar tres métodos de estimación de la edad dental (ED) con fines forenses.

Material y métodos:

Se seleccionaron 512 radiografías panorámicas de sujetos de Maracaibo, estado Zulia, Venezuela, de ambos sexos (272 hembras y 240 varones), con edades cronológicas (EC) entre 6-18 años. Se asignaron los estadios de maduración propuestos por Nolla, Moorrees et al y Demirjian et al a siete dientes mandibulares permanentes del lado izquierdo, la ED fue calculada de acuerdo con la metodología de cada autor. Se obtuvo la EC en la cual se observaron los diferentes estadios de maduración, así como las diferencias de media entre la EC y la ED estimada por cada método mediante un test de Student para muestras relacionadas.

Resultados:

En general, las hembras alcanzaron los estadios de maduración a edades más tempranas que los varones. Se evidenció en el total de la muestra, una sobreestimación de la edad para el método de Demirjian et al (-0.14 ± 1.45), mientras que para el de Nolla y Moorrees et al se observó una subestimación, esta subestimación fue mayor para el método de Moorrees et al (2.63 ± 2.09) que para el de Nolla (0.42 ± 1.38), siendo que las diferencias encontradas entre la EC y la ED fueron estadísticamente significativas.

Conclusión:

Se determinó que para el total de la muestra, el método de Demirjian et al fue el más preciso.

Palabras clave: Desarrollo dental; edad dental; método de Nolla; método de Moorrees; método de Demirjian

INTRODUCTION

Dental age (DA) is considered a reliable indicator of chronological age (CA), and has been used in dentistry with the aim of determining whetherdentalmaturationofl I the patient is found to be within average for his age group, It has also been used for live or deceased individuals lacking valid identification documents.1,2,3 In this sense, DA determination during childhood (0-14 years) includes all dental groups in maturation stages, whereas third molars are used in adolescence and early adulthood (14-21 years), since those teeth are still developing in this period. Forensic age calculation in children and adolescents, also includes assessment of anthropometric indicators, secondary sexual traits (characters) as well as maturation radiographic assessment, where recognition of development disorders which might influence age calculations are of the utmost importance.4,5,6

Among methods used to assess dental maturation we can count those of Nolla,7 Moorrees et al8 and Demirjian et al.1 Nollas method7 divides dental development in 11 stages, which comprise from «0», absence of the crypt until apical closure of single and multi-rooted teeth. To apply this method, a quadrant of the upper or lower jaw can be selected, or even the complete arch, either including or not including the third molar. Each tooth has an assigned stage, represented by punctuation; these punctuations are added and scores (points) are obtained, which are then transformed into DA by means of reference tables for each gender.

Even though the method of Moorrees et al8 proposes assignation of maturation stages for crown and root, these can vary in number according to whether the tooth is single rooted or multi-rooted. Once the stage is selected, DA is inferred through graphs which allow to know the age in which the stage is observed for this particular tooth, this enables calculation through evaluation of a single tooth, or through average of corresponding ages to stages assigned to a group of teeth.

On the other hand, Demirjian et al1 method presents eight stages of maturation, named with letters from A to H which represent formation of all seven left side mandibular teeth. A punctuation corresponds to each stage, after that, points are added, and the resulting score is transformed into DA, using reference tables for each gender. For stage assignation, authors propose in addition to schematic images, radiographic images and description.

Several studies have been conducted to assess applicability of these methods to subjects with ethnic, socioeconomic and environmental characteristics different from those of the samples used in their elaboration, bearing in mind that most have been conducted in European subjects,9,10,11 Asian,12 African13 and subjects residing in Oceania.14 In Latin America, research has been reported in Argentinian,15 Brazilian,16,17 Chilean,18 Colombian,19 Paraguayan,20 Peruvian21,22 and Mexican23 subjects.

In reports coming from Venezuela, we can mention research conducted by Cruz-Landeira et al2 in Native Americans of Merida, State of Merida, in the Andean zone of the country; research conducted by Medina3 in children from Caracas' Metropolitan area and the west; Tineo et al24 and Ortega-Pertuz et al25 in subjects from Maracaibo, State of Zulia.

Considering the fact that tooth maturation studies are scarce in Latin America, especially so in Venezuela, and also considering that DA is an important indicator for a forensic age diagnosis, the present research project has the aim of comparing methods of Nolla,7 Moorrees et al8 and Demirjian et al1 in a sample of subjects from Maracaibo, State of Zulia.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sample

The study's population was composed of panoramic X-rays of patients attending CIAN (Centro Integral de Atención al Niño, Center for Comprehensive Childcare) and from the Forensic Dentistry Area Files (Research institute, School of Dentistry, University of Zulia). The sample was composed of 512 panoramic X-rays of subjects of both genders (272 females, 240 males), aged 6-18 years. The following inclusion criteria were used to select X-rays: absence of systemic disease as well as size and weight according to CA as stated in the previous clinical history. Images with sufficient contrast and density, minimal distortion, presence of all seven permanent mandibular teeth in the left side, in case of some missing tooth, the homologous tooth in the opposite side was considered, absence of extensive disease and number anomalies, shape, size or position which might alter odontogenesis.

Age groups for each gender were composed so as to have groups of at least 10 subjects with age difference amongst them of 11 months. Real age was calculating by subtracting birth date from date of X-ray procurement.

Techniques and procedure

Procurement of X-ray images

X-rays selected from CIAN were digitalized with a photographic camera (Sony Cybershot DSC-W650. Sony Corporation, Tokyo Japan) with 300 dpi resolution. In order to obtain an image, the radiograph was placed on a desk negatoscope, in an environment with dimmed light, no flash and framed a withmatteblackcardboard. At a later point these images were stored in a computer and transformed to a scale of grey in order to be interpreted. Panoramic X-rays selected from the Forensic Dentistry Area were physically available for analysis.

Tooth maturation analysis and DA calculation

All conventional and digital panoramic images were assessed by a single, previously gauged observer, who only possessed knowledge of the subject's gender. Digital images were analyzed using software Adobe Photoshop CS6 version (Adobe System Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA). The operator could use resources of brightness (shine), contrast and magnification of the software. Conventional panoramic radiographs were placed on a desk negatoscope with a matte black mask to improve their observation in an environment of dimmed light. In these studied methods, only the seven left lower permanent teeth were evaluated.

In cases when Nolla7 method was applied, radiographic evaluation was performed of mineralization grade of studied permanent teeth, and corresponding stage was assigned represented as punctuation according to the method. Following author's instructions, in cases when studied tooth was found to be between two stages, a value of 0.5 was added to the punctuation; in those cases when it showed development slightly above than that described by stage, 0.2 was added to assigned score (punctuation); in cases when the tooth exhibited a slightly lesser development to the following stage, 0.7 was added. Obtained scores were added and result was transformed into DA by means of tables standardized for each gender.

In the case of Moorrees et al8 method, proposed stages were identified in studied teeth. After this, a certain age was assigned to each tooth according to the stage reached using Smith's26 table; after this, these age scores were averaged so as to obtain the subject's DA. In Demirjian et al1 method, selection of stages and DA calculation were accomplished following procedure described by the author. Data were recorded in a specially tailored chart.

Statistical analysis

Statistical package SPSS version 15.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS Inc. Chicago Ill, USA) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were obtained (mean, standard deviation) of chronological ages at which different maturation studies of studied methods were observed. Likewise, means of dental ages for both genders as determined by each method were calculated. Mean differences betweenDAanddentalH ages obtained in each method were determined. This was achieved with a T Student test for related samples, thus, in the present study, a negative symbol implied age over-estimation, and a positive sign represented a subestimation. Assumed significance level was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Tables I-III (II) show results of chronological ages means obtained for maturation stages of all three methods. In general, in all three methods, females reached these stages at earlier ages than males.

Table I Means and standard deviations of chronological ages (years) where maturation stages of the Nolla method are observed for both genders.

F = Female, M = Male, SD = Standard deviation, Me = median.

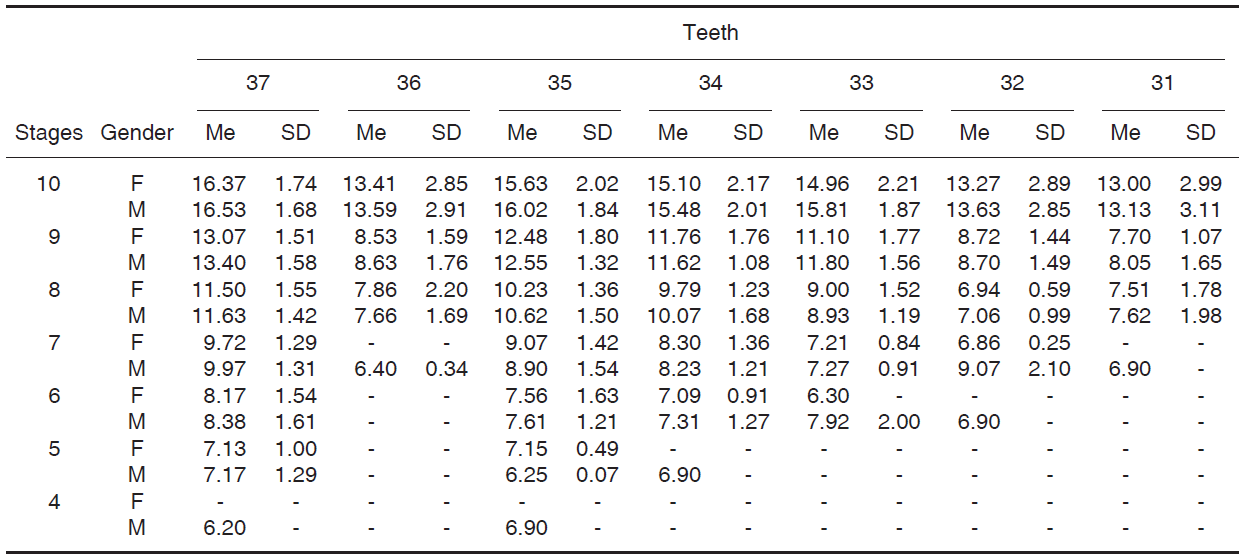

Table II Means and standard deviations of chronological ages (years) where maturation stages are observed for both genders according to Moorrees et al method.

F = Female, M = Male, SD = Standard deviation, Me = median.

Table III Means and standard deviations of chronological ages (years) where maturation stages for both genders can be observed according to Demirjian et al method.

F = Female, M = Male, SD = Standard deviation, Me = median.

Table IV shows mean difference between CA and DA calculated for each method used in the present study. It was observed in the total sample that there was ageover-estimation in the Demirjian et al method,1 whereas Nolla's7 and Moorrees et al methods8 subestimation was observed, which was more pronounced in Moorrees et al method.8 Differences found among variables were statistically significant; Demirjian et al method1 exhibited lesser difference with CA. In Demirjian et al's method1 calculated aged over-estimation was observed for both genders, this being significant for males, whereas in Nolla7 and Moorrees et al methods8 under-estimation, with statistical significant differences was observed; among these two, Moorrees et al method8 exhibited greater under-estimation.

Table IV Mean and mean difference between chronological age and dental age estimated with different studied methods.

‡ t test for related samples.

F = Females, M = Males, CA = Chronological age, DA = Dental age, SD = Standard deviation, CI = Confidence interval, Max. = Maximum, Min. = Minimum, Sig. = Significance (p < 0.05).

Tables V and VI show mean and mean difference between CA and DA, calculated through all three methods used in the present study and distributed by gender and age group. In groups 6 and 8 years old, females (Table V) exhibited age over-estimation in the Nolla7 method, whereas in groups 7 and 9-18 years, age subestimation was observed with variance ranging 0.02 ± 0.51 to 2.61 ± 0.30 years; these differences were statistically significant for groups 11 and 16-18 years. Moorrees et al' s method8 exhibited consistent age underestimation in all groups, with variation ranging from 0.20 ± 1.14 to 7.61 ± 0.231 years; these differences were statistically significant with exception of the six year old group.

Table V Mean and mean differences between chronological age and dental age estimated with different studied methods according to age group for females.

‡ t test for related samples.

AG = Age group, F = Females, M = Males, CA = Chronological age, DA = Dental age, SD = Standard deviation, CI = Confidence interval, Max. = Maximum, Min. = Minimum, Sig. = Significance (p < 0.05).

Table VI Mean and mean differences between chronological age and dental age estimated with different studied methods according to age group for males.

‡ t test for related samples.

AG = Age group, F = Females, M = Males, CA = Chronological age, DA = Dental age, SD = Standard deviation, CI = Confidence interval, Max. = Maximum, Min. = Minimum, Sig. = Significance (p < 0.05).

In the Demirjian et al1 method, age a statistically significant over-estimation was observed in groups 6-11 years, varying in ranges -0.51 ± 1.13 to -1.29 ± 1.18 years age subestimation was observed from group 12-18 years onwards; differences were only statistically significant for groups 15-18 years.

In males, table VI showed age overestimation in age in groups 6-8 and 13 years with the Nolla method;7 these differences were statistically significant for groups six and seven years. Age under-estimation was observedingroupsof9, 10, 12, 14 and 15 years. In groups of 11, 16-18 years, age under-estimation was observed, with variation ranging 0.50 ± 0.97 to 2.50 ± 0.58 years, with statistically significant differences. Moorrees et al method8 exhibited age under-estimation ranging from 0.45 ± (0.82) to 6.64 ± (0.30), with statistically significant differences for all groups.

Consistent age over-estimation was observed in Demirjian et al1 with statistically significant differences between CA and DA in groups 6-14 years, which varied from -022 ± 1.15 to -1.26 ± 0.73 years, except for the group 15 years. Age subestimation was observed from group 16 years onwards varying from 0.75 ± (0.98) to 2.34 ± (0.30) with statistically significant differences.

Graphs were built, to represent comparison between estimated CA and DA means according to all three methods in age groups for both genders (Figures 1 and 2). With respect to CA, more proximity was observed in Nolla's7 and Demirjian's1 et al method. Moorrees8 et al method exhibited least proximity to CA, showing under-estimation.

DISCUSSION

DA is included in the forensic age diagnosis of subjects with teeth in maturation process.4,5 In the present research Nolla's,7 Moorrees at al8 and Demirjian et al1 methods were used; DA was compared to CA with the aim of acknowledging which method was more accurate in ages calculation.

When maturation stages proposed by each method were identified in X-rays, it was clear that, regardless of method employed, females reached stages at earlier ages than males, this is concurrent with other authors' reports.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24

In Nolla's7 method, results revealed age underestimation for the whole sample in both genders, values obtained were lesser than those found in children in Bangladesh,27 Turkey28 and United Kingdom.27 With respect to Latin American samples, underestimation in the present study was similar to that found in Argentinians15 and Peruvians21 and lower to that found in Brazilians.17 In the case of Venezuelans, Medina3 reported values above those found in the present study.

With respect to Moorrees et al8 method, obtained results showed age under-estimation in males and females for the full sample, in discordance with that found for Colombians.19 Under-estimation values found in the present research were higher than those reported in South Africans29 and Venezuelans.3

With respect to Demirjian et al method1 a consistent age over-estimation was observed. In males, age over-estimation was higher than that observed in Iranians, and lesser in both genders than that reported in subjects from Saudi Arabia,12 Australia,14 Belgium,9 Spain,10 France11 and Senegal.13 In Latin America, reports obtained in the present research were lesser than those reported for Argentinians,15 Brazilians,16 Chileans,18 Paraguayans20 and Peruvians.22 For Venezuelans, this over-estimation was observed in children of Caracas Metropolitan Areas3 and Zulia inhabitants24,25 whereas in people from Merida,2 age was underestimated when applying the method.

When comparing differences between CA and DA in the total sample, it could be observed that Demirjian et al method1 showed lower values for both genders, this coincides with that observed in subjects from Bangladesh and the United Kingdom,27 whereas Nolla's method7 was more accurate for Indians30 and Turks.30 Findings reported in the present work coincide with those of Gutierrez21 conducted in Peruvians, who compared Nolla's7 and Demirjian et al1 methods and those observed by Medina3 in Venezuelans.

When mean differences between estimated CA and DA were analyzed through the three methods here studied, distributed according to gender and age, it could be observed that Nolla's7 method for both genders and Demirjian et al1 method for females, that groups comprised between 9 and 15 years did not exhibit statistically significant differences. On the other hand, in age groups comprised between 6-9 and 15-18 years, differences between estimated CA and DA estimated thorugh all three methods were statistically significant. This dynamic process between age groups could be influenced by the variability in tooth maturation process exhibited by the studied sample, when compared to subjects in the sample used to build original methods.

Differences found between DA and CA estimated in all three methods, clearly reflect influence exerted by genetic and environmental factors such as heredity, nutrition, health status of the subject, ethnicity, social and financial level, climatologic factors, among others, which intervene and modify human development processes; these factors vary from one population to the next, therefore it is imperative to adapt these methods to the study methods, whose characteristics are different from those of subjects studied in the samples of original methods.2,3,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30

All three applied methods exhibited usefulness in age forensic diagnosis, considering acceptable an error margin of ± 2-3 years in DA estimation, taking into account that DA must be used alongside the study of size and weight, presence of secondary sexual traits as well as bone age.4,5,6

CONCLUSIONS

Dental maturation stages assigned through studied methods were reached at earlier ages in females. It was verified that for Nolla's7 and Moorrees et al8 methods greater age underestimation was obtained; Moorrees et al method8 exhibited greater underestimation, and thus was considered the less precise of both, whereas overestimation was observed in Demirjian et al1 method.

Of all three presented methods, Demirjian et al method1 exhibited greater accuracy in dental age estimation for the whole studied sample. Although assessed methods showed applicability for age estimation for forensic purposes, it is necessary to adapt them to the studied populations, since these populations might exhibit different ethnic characteristics, environmental factors and social and financial circumstances than the populations used to build standardization of these methods. In order to obtain suitable age calculation, DA must be evaluated along with size, weight, presence of secondary sexual traits and bone age.

REFERENCES

1. Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Human Biol. 1973; 45(2): 211-227. [ Links ]

2. Cruz-Landeira A, Linares-Argote J, Martínez-Rodríguez M, Rodríguez-Calvo MS, Otero XL, Concheiro L. Dental age estimation in Spanish and Venezuelan children. Comparison of Demirjian and Chaillet's scores. Int J Legal Med. 2010; 124: 105-112. [ Links ]

3. Medina AC. Comparación de cinco métodos de estimación de maduración dental en un grupo de niños venezolanos [Trabajo para optar a la categoría de Profesor Asociado]. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela; 2011. [ Links ]

4. Prieto JL, Barbería E, Ortega R, Magaña C. Evaluation of chronological age based on third molar development in the Spanish population. Int J Legal Med. 2005; 119(6): 349-354. [ Links ]

5. Olze A, Reisinger W, Geserick G, Schmeling A. Age estimation of unaccompanied minors. Part II. Dental aspects. Forensic Sci Int. 2006; 159 Suppl 1: S65-S67. [ Links ]

6. Study Group of Forensic Age Estimation of the German Association of Forensic Medicine. Criteria for age estimation in living individuals. [Citado el 11 de Julio de 2016]. Disponible en: https://campus.unimuenster.de/fileadmin/einrichtung/agfad/empfehlungen/empfehlung_strafverfahren_eng.pdf. [ Links ]

7. Nolla CM. The development of the permanent teeth. J Dent Child. 1960; 27: 254-266. [ Links ]

8. Moorrees CFA, Fanning EA, Hunt EE. Age variation of formation stages for ten permanent teeth. J Dent Res. 1963; 42(6): 1490-1502. [ Links ]

9. Willems G, Van Olmen A, Spiessens B, Carels C. Dental age estimation in Belgian children: Demirjian's technique revisited. J Forensic Sci. 2001; 46(4): 893-895. [ Links ]

10. Feijóo G, Barbería E , De Nova J, Prieto JL . Permanent teeth development in a Spanish sample. Application to dental age estimation. Forensic Sci Int. 2012; 214(1-3): 213.e1-213.e6. [ Links ]

11. Urzel V, Bruzek J. Dental age assessment in children: a comparison of four methods in a recent French population. J Forensic Sci. 2013; 58 (5): 1341-1347. [ Links ]

12. Al-Emran S. Dental age assessment of 8.5 to 17 Year-old Saudi children using Demirjian's method. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008; 9(3): 64-71. [ Links ]

13. Ngom PI, Faye M, Ndoye-Ndiaye F, Diagne F, Yam AA. Applicability of standard of Demirjian's method for dental maturation in Senegalese children. Dakar Med. 2007; 52(3): 196-203. [ Links ]

14. Flood SJ, Franklin D, Turlach BA, McGeachie J. A comparison of Demirjian's four dental development methods for forensic age estimation in South Australian sub-adults. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013; 20(7): 875-883. [ Links ]

15. Pobletto A, Giménez E. Edad dentaria: adecuación regional de los métodos de Nolla y Demirjian. UNcuyo. 2012; 6(2): 37-42. [ Links ]

16. Eid RM, Simi R, Friggi MN, Fisberg M. Assessment of dental maturity of Brazilian children aged 6 to 14 years using Demirjian's method. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002; 12(6): 423-428. [ Links ]

17. Kurita LM, Menezes AV, Casanova MS, Haiter-Neto F. Dental maturity as an indicator of chronological age: radiographic assessment of dental age in a Brazilian population. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007; 15(2): 99-104. [ Links ]

18. Cadenas RI, Celis CC, Hidalgo RA, Schilling QA, San Pedro VJ. Estimación de edad dentaria utilizando el método de demirjian en niños de 5 a 15 años de Curicó, Chile. Int J Odontostomat. 2014; 8(3): 453-459. [ Links ]

19. Corral C, García F, García J, León P, Herrera AM, Martínez C et al. Edad cronológica vs. edad dental en individuos de 5 a 19 años: un estudio comparativo con implicaciones forenses. Colomb Med. 2010; 41(3): 215-223. [ Links ]

20. Funk B, Costa M, Charmeux A. Estudio comparativo y evaluación de la validez de dos métodos de estimación de la edad dental en una muestra de niños de la población paraguaya: métodos de Demirjian y Willems. Paraguay Oral Res. 2015 [Citado el 11 de julio de 2016]; 4(1). Disponible en: http://www.paraguayoral.com.py/revista/a4v1/A4N1-ART1.pdf. [ Links ]

21. Gutiérrez DT. Comparación de la precisión de los métodos de Nolla y Demirjian para estimarla edad cronológica de niños peruanos [Tesis para optar el título profesional de Cirujano Dentista]. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; 2015. [ Links ]

22. Peña CE. Estimación de la edad dental usando el método de Demirjian en niños peruanos [Tesis para optar el título profesional de Cirujano Dentista]. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; 2010. [ Links ]

23. Arciniegas NM, Ballesteros M, Meléndez A. Análisis comparativo entre la edad ósea, edad dental y edad cronológica. Rev Mex Ortodon. 2013; 1(1): 33-37. [ Links ]

24. Tineo F, Espina de Fereira AI, Barrios F, Ortega A, Fereira J. Estimación de la edad cronológica con fines forenses, empleando la edad dental y la edad ósea en niños escolares en Maracaibo, estado Zulia. Acta Odontol Venez. 2006; 44(2): 184-191. [ Links ]

25. Ortega-Pertuz AI, Martínez VM, Barrios F. Maduración dentaria en jóvenes venezolanos mediante el método de Demirjian y colaboradores. Acta Odontol Venez. 2014[Citado el 11 de julio de 2016]; 52(3). Disponible en: http://www.actaodontologica.com/ediciones/2014/3/art13.asp. [ Links ]

26. Smith, Holly B. Standards of human tooth formation and dental age assessment. In: Kelley MA, Spencer CL editors. Advances in dental anthropology. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1991. pp. 143-168. [ Links ]

27. Maber M, Liversidge HM, Hector MP. Accuracy of age estimation of radiographic methods using developing teeth. Forensic Sci Int. 2006; 159 Suppl 1: S68-S73. [ Links ]

28. Nur B, Kusgoz A, Bayram M, Celikoglu M, Nur M, Kayipmaz S et al. Validity of Demirjian and Nolla methods for dental age estimation for Northeastern Turkish children aged 5-16 years old. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012; 17(5): e871-e877. [ Links ]

29. Phillips VM, van Wyk Kotze TJ. Testing standard methods of dental age estimation by Moorrees, Fanning and Hunt and Demirjian, Goldstein and Tanner on three South African children samples. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2009; 27 (2): 20-28. [ Links ]

30. Rai B, Anand SC. Tooth developments: an accuracy of age estimation of radiographic methods. World J Med Sci. 2006; 1(2): 130-132. [ Links ]

** This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/facultadodontologiaunam

Received: July 2016; Accepted: February 2017

text in

text in