Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista odontológica mexicana

Print version ISSN 1870-199X

Rev. Odont. Mex vol.19 n.2 Ciudad de México Apr./Jun. 2015

Case report

Endodontic patient with rhinocerebral mucormycosis: clinical case report

Héctor Hernández Méndez* and Alejandra Rodríguez Hidalgo§

* Teacher.

§ Professor.

Endodontics Specialty, Graduate and Research School, National School of Dentistry, National University of Mexico (UNAM).

ABSTRACT

A patient previously diagnosed with cerebral mucormycosis attended the Endodontics Clinic of the Graduate and Research School, National School of Dentistry, National University of Mexico (UNAM). This article presents variations in the clinical handling of the patient; stress is made on the importance of preserving the greatest number of teeth in the mouth to thus achieve better stability of the palatal obturator and establish suitable phonation and mastication functions.

Key words: Rhinocerebral mucormycosis, zygomycosis, palate necrosis.

INTRODUCTION

Mucormycosis, also called zygomycosis or phycomycosis is an uncommon, opportunist, acute infection with high morbidity rate. It is caused by a certain number of fungi species, classified in the Mucorales order of the Zygomycetes class, among which Rhizopus, Mucor and Absidia can be found.1 These saprophyte fungi can be isolated in fruit, vegetables or water, but they are more common in hospital environments.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

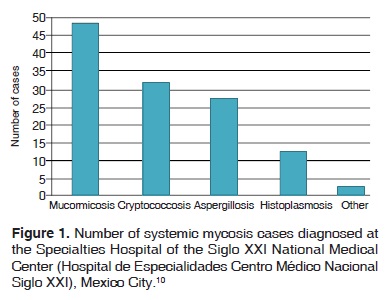

Mucormycosis is present worldwide, and, as many other low pathogenic capacity fungi infections, it requires weakening factors in the host. According to the clinical variety, among conditions which favor the development of this infection we can count: unbalanced diabetes mellitus, leukemia, treatments with anti-inflammatory steroids, prolonged treatment with acetylsalicylic acid, and in recent years, many cases of HIV-associated mucormycosis have been published2-8 (Figure 1).

The most frequent clinical presentation is the rhinocerebral variety; this is one of the fungal infections exhibiting most rapid advance in humans. It generally has its onset in the nose and para-nasal sinuses.9

General mortality rate due to mucormycosis is 44% in diabetic patients, 35% in patients lacking underlying diseases, and 66% in patients with malignant tumors. Mortality rates vary according to the infection location: 96% in patients with disseminated infections, 85% in patients with gastrointestinal infections and 76% in patients with lung infections.11

CLINICAL CASE

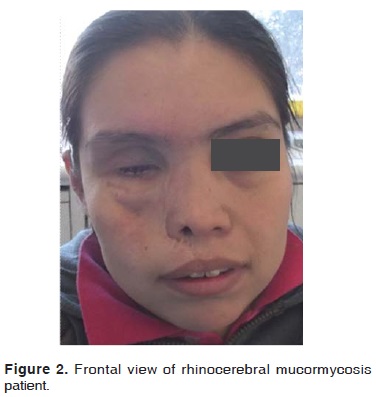

A 20 year old female patient attended the clinical service of the Endodontics Department at the Graduate and Research School of the National School of Dentistry, National University of Mexico (UNAM) (Figures 2 and 3). The patient had been referred from the <<Manuel Gea González>> Hospital in order to receive root canal treatment in teeth which so required.

HISTORY

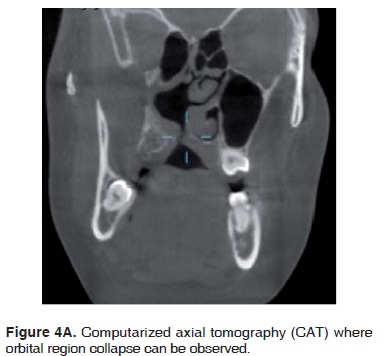

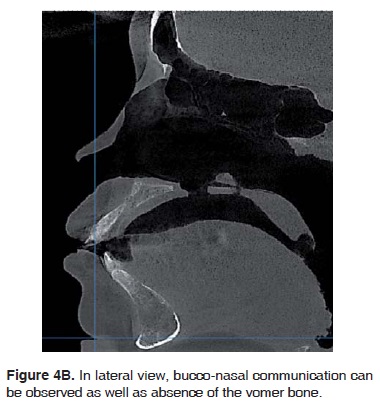

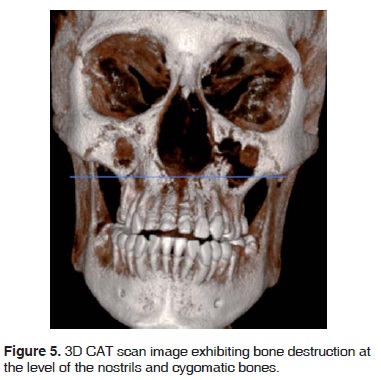

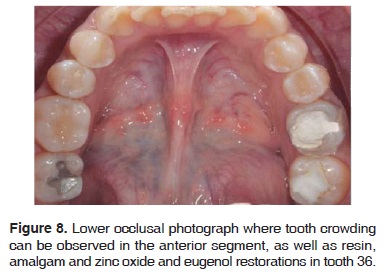

The patient had been infected with the fungus in a hospital environment, where she had been admitted due to a sinusitis process; at that moment the patient suffered a depressed immunological system. Personal pathological history of the patient was: rhinocerebral mucormycosis at age 14, followed by cerebral thrombosis, cerebral infarction, state of coma for three months, partial paralysis of the left side of her body as well as muscle spasms at the level of the hip, neck and head. In order to remove fungus-affected tissues, the patient had been operated on the ocular globe, nose, cygomatic bones and palate (Figures 4A and B, 5 to 8)(6, 7).

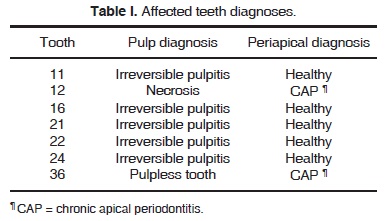

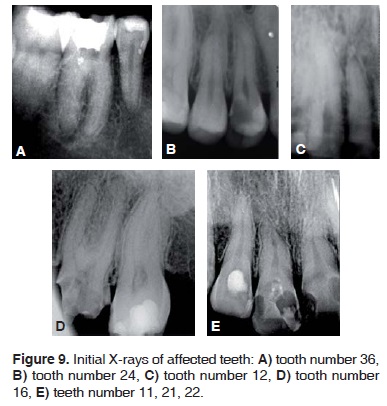

At the Endodontic Department, during the course of one year, root canal treatment was conducted on teeth number 11, 12, 16, 21, 22, 24 and 36 (Table I and Figure 9). The patient was sent to the Advanced Restorative Dentistry Department for rehabilitation, she was equally sent to the Maxillofacial Prosthesis Department in order to manufacture a provisional obturator and an ocular depth device.

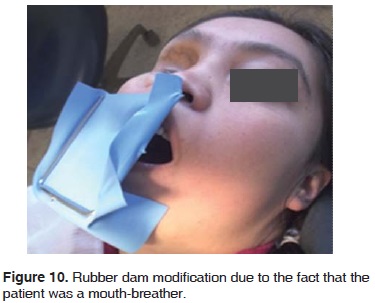

Due to the muscle spasms at the hip which afflicted the patient, appointments for clinical treatment had to be short. When considering involuntary movements due to muscle contractions at the head and neck, the use of rotary systems had to be carefully handled in order to prevent instrument fracture. In this case, 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCL) solutions were used. In all treatments working lengths were obtained with an electronic foramina locator. As final irrigation, a sequence or 2.5% NaOCL, bi-distilled water, 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), bi-distilled water and alcohol was used. Sealapex (Sybron/Kerr®) was the cement used. Teeth with diagnoses of pulp necrosis or teeth without pulp were filled at a second appointment. Between appointments, these teeth were medicated with calcium hydroxide.Theuseofisolation procedures with a rubber dam had to be modified in all appointments, so as to allow a more accessible airway for the patient, since, due to previous surgeries she experienced difficulties in properly breathing through the nose (Figures 10 and 11).

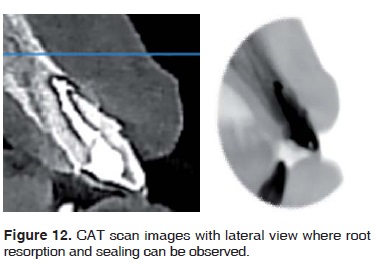

Tooth number 21 exhibited root resorption, which was ascertained with placement of calcium hydroxide and iodoform as a contrasting medium. After this, it was filled up to the length indicated by the foramina electric locator (Figure 12).

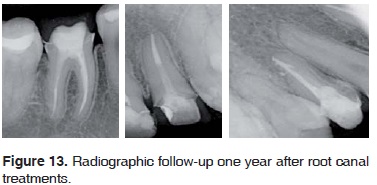

At the one year follow-up visit, the following was observed: in teeth number 12, 24 and 36 periapical status reparation was observed where chronic apical periodontitis (CAP) existed, as well as placement of glass fiber posts conducted by clinicians of the Advanced Restorative Dentistry Department (Figure 13). Metal-porcelain crowns were placed on teeth 36, 24, resin was applied to tooth 22; teeth 11, 12 and 21 were prepared for crowns, and provisional crowns were placed.

At the department of Maxillofacial Prosthesis a provisional obturator was designed, moreover the patient was instructed on how to use an ocular deepening device, in preparation for a later placement of ocular prosthesis.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Antonio Barron et al, in 2001 mentioned that this disease was present in immune-compromised patients, 70% in patients with type II diabetes mellitus.12 Dr.Jung et al, in 2009 presented a series of 12 cases of rhinocerebral mucormycosis, in which they observed a 50% mortality rate when only drug therapy was used, whereas patients who had undergone surgical treatment along with drug treatment, exhibited 30% mortality rate.13 According to reviewed scientific literature, computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful in diagnostic studies of rhinocerebral mucormycosis, nevertheless, it has been found that MRI exhibited greater sensitivity to study intra-cranial area and peri-orbital tissue.14,15

CONCLUSIONS

This type of patients are more reluctant to accept medical-surgical procedures, since for them, emotional and psychological factors play an important role. In those cases where there is excessive palatine bone loss, it is essential to preserve the greater number of teeth in the mouth so as to achieve stability with the obturator.16 In cases when the palatine bone defect is very extensive and affects root surfaces, NaOCL irrigation will need to be modified, resorting to lower concentrations, in order to avoid irritation to adjacent tissues caused by a possible extrusion. Interdisciplinary handling of these patients is essential in order to achieve greater success in undertaken treatments. It must be borne in mind that clinical skills must be based upon biological knowledge.

REFERENCES

1. Pía W, Spalloni M, Glaser S, Verdugo P. Mucormicosis rinocerebral, sobrevida en un niño con leucemia. Rev Chil Infect. 2004; 21: 53-56. [ Links ]

2. Sugar AM. Agentes de la mucormicosis y especies relacionadas. En: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R Eds. Enfermedades infecciosas. Principios y práctica. 4a ed. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Médica Panamericana; 1997: pp. 2595-2606. [ Links ]

3. Wiedermann BL. Zigomicosis. En: Feigin RD, Cherry JD (Eds). Tratado de infecciones en pediatría. 4a ed. México, DF: Interamericana McGraw-Hill; 1995: pp. 2180-2186. [ Links ]

4. Rippon JW. Zygomycosis. In: Rippon JW (Ed). Medical mycology. The pathogenic actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988: pp. 697-703. [ Links ]

5. Scholer HJ, Müller E, Schipper MA. Mucorales. The pathogenic species of mucor. Occurrence as pathogens. In: Howard DH, Howard LF (Eds). Fungi pathogenic for humans and animals. New York: Marcel Deckker; 1983: pp. 44-45. [ Links ]

6. Neame P, Rayner D. Mucormycosis. Arch Pathol. 1960; 70: 143-150. [ Links ]

7. Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. Mucormycosis. Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea Febiger; 1992: pp. 524-559. [ Links ]

8. Tedder M, Spratt JA, Anstadt MP. Pulmonary mucormycosis: results of medical and surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994; 57: 1044-1050. [ Links ]

9. Arnáiz ME, Alonso D, González MC, García JD, Sanz JR, Arnáiz AM. Cutaneous mucormycosis: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009; 62: 434-441. [ Links ]

10. Méndez-Tovar LJ. Unidad de Investigación Médica, Hospital de Especialidades C.M.N. Siglo XXI. UNAM, 2011.

11. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholaryet O. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54 (S1): S23-34. [ Links ]

12. Barron-Soto MA, Campos-Navarro LA. Morbilidad y mortalidad del paciente con mucormicosis rinorbitaria posterior al tratamiento médico quirúrgico oportuno. Cir Ciruj. 2001; 69: 8-11. [ Links ]

13. Jung SH, Kim SW, Park ChS, Song ChE, Cho JH, Lee JH et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: consideration of prognostic factors and treatment modality. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009; 36: 274-279. [ Links ]

14. Terk MR et al. MRI imaging in rhinocerebral and intracranial mucormycosis with CT and pathologic correlation. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992; 10: 81-7. [ Links ]

15. Garces P, Mueller D, Trevenen C. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a child with leukemia: CT and MRI findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1994; 24: 50-51. [ Links ]

16. Rodríguez-Hidalgo A, Jácome-Musule JL, García-Aranda LR. Murcomicosis oral y su implicación endodóncicas. Endodoncia. 1998; 2: 9-12. [ Links ]

Note This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/facultadodontologiaunam Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Héctor Hernández Méndez

E-mail: cd.hector_hernandez@hotmail.com

text in

text in