Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Culturales

versión On-line ISSN 2448-539Xversión impresa ISSN 1870-1191

Culturales vol.5 no.9 Mexicali ene./jun. 2009

Artículos

How Immigrants Have Shapped Uruguay

Felipe Arocena

Universidad de la República-Uruguay.

Fecha de recepción: 2 de julio de 2008

Fecha de aceptación: 31 de octubre de 2008

Abstract

This paper will make a comparative analysis of how nine immigration groups and a black population brought as slaves have shaped the culture of Uruguay. The most common image of Uruguay, at home and also abroad, is of a homogeneous and Europeanized country built by immigrants from Spain and Italy, without a large Afro population and with no natives. This image is at best only half the truth, because there have also been contributions from immigrants from Asia, Russia, other European countries, and also from African slaves and their descendants. In particular we will analyze how people of African descent, Basques, Italians, Swiss, Russians, Armenians, Lebanese, Jews, Muslims, and Peruvians have contributed to building the Uruguayan nation, and examine what their impact on Uruguayan society and culture has been. This paper presents the most important conclusions from research based on almost one hundred in-depth interviews with people descended from these communities.

Keywords: assimilation, multiculturalism, immigration, Uruguay.

Resumen

Este texto presenta un análisis comparativo de cómo nueve grupos de migrantes y un sector de población negra, llevados como esclavos, han conformado la cultura de Uruguay. La imagen más común de Uruguay, tanto en el propio país como en el extranjero, es la de una nación homogénea y europeizada construida por inmigrantes de España e Italia, sin la presencia de una gran población de ascendencia africana y sin nativos. Esta imagen, en el mejor de los casos, es una verdad a medias, porque también ha habido contribuciones de inmigrantes de Asia, de Rusia, de otros países europeos y también de esclavos africanos y sus descendientes. En particular analizaremos cómo personas de ascendencia africana, vascos, italianos, suizos, rusos, armenios, libaneses, judíos, musulmanes y peruanos han contribuido en la construcción de la nación uruguaya. Asimismo, examinaremos el impacto de esta migración en la sociedad y la cultura de Uruguay. Este texto presenta las conclusiones más importantes de una investigación fundamentada en casi cien entrevistas a profundidad con personas descendientes de dichas comunidades.

Palabras clave: asimilación, multiculuralismo, inmigración, Uruguay.

Introduction1

This introduction will give a brief outline of Uruguay's social context, so it is mainly descriptive. In the second part of the paper I adopt an ethnographic approach to present the contributions that immigrants have made, through the voice of their descendants. In the third and final part I employ an analytical framework to enhance understanding of the shift towards multiculturalism that is operating in some of these communities.

Uruguay is a small country with a population of 3.4 million people, and according to recent estimates it will have approximately the same number of inhabitants in 2025; so in fact demographic growth is paralyzed. There are three main causes of this paralysis: first, the birth rate is an average of 2.04 children per family, which is as low as the levels in European countries; second, for at least the last thirty years Uruguayans have been moving abroad en masse, and this Diaspora, which includes two generations, has been estimated at one million people; and third, since the Second World War the country has received no significant influx of new immigrants. Consequently Uruguay is an empty land, with half the population concentrated in the capital city, Montevideo. This profile contrasts sharply with Costa Rica in Central America, for example, which has one million more people and a surface area that is four times smaller.

The vast majority of Uruguayans, 87%, are white, only 9% are of African descent, 3% of native descent, and 1% are from other ethnic groups (INE, 2006). The main original populations that lived in the country until the 19th century -Guaraníes and Charrúas- were few in number. The former were assimilated through the Catholic Church and the mixing of races, and the latter were exterminated: they were the victims of genocide in 1831, just after Uruguayan independence. At beginning of the 19th century blacks accounted for almost thirty percent of the capital city's population, but after slavery came to an end and new permanent immigrants settled in the country this proportion was considerably diluted, and today one out of ten Uruguayans identifies himself as black.

Uruguay was once described as the "dimmest star of the Catholic firmament in Latin America", and although there has been a continuous process of secularization, 47% of the population declare they are Catholic, 11% are Christian but not Catholic, 23% believe in God but do not belong to any church, and another 2% belong to other religions such as Judaism or Afro cults. The remaining 17% do not believe in God or are agnostics (INE, 2006).

Spanish is the official language of the country and it is spoken by the whole population, even in private. There are some variations of the language along the western border with Brazil, where a mix of Portuguese and Spanish is spoken.

In almost every international aggregated indicator associated with development, Uruguay ranks high when compared with the rest of the world. In the United Nations Human Development Index (2006) the country is ranked 43rd and is classed in the high development group. In the Democracy Index (2007) created by The Economist, Uruguay ranks 27th out of 167 countries and it is considered a full democracy. In the Environmental Sustainability Index (2005) drawn up by the Universities of Yale and Columbia, Uruguay is 3rd, and on the Environmental Performance Index (2008) it comes 36th out of 149 countries.

In 2002 the country underwent the worst economic crisis in its history and almost one third of the population fell below the poverty line. The causes for this were partly structural and partly due to the prevailing economic conditions. The long term causes included very slow economic growth since the 1950s due to the country's lack of an industrialized base, and a failure to incorporate the latest innovations of the technological revolution or adapt to the information age. The Uruguayan economy was still completely dependent on the export of primary goods for which international prices had been steadily decreasing in the long term. A more immediate factor that had a big negative impact was the complete collapse of Uruguay's financial system, which stemmed from a run on the banks that spread from neighboring Argentina, which had its own economic crisis on 2001. As the popular saying goes, 'When Argentina sneezes, Uruguay catches the flu'. But since 2004 Uruguay has made an impressive economic recovery with annual GNP per capita growth of 7 to 12%, which is unprecedented in the last 60 years. However, there are still serious unsolved problems: almost half the population under 12 years old are living below the poverty line, and new generations are being born in very adverse social and economic conditions. One out of four Uruguayans are living below the poverty line and 2% are destitute. The main factor in the economic recovery has been very high international prices for food products, especially meat, soy, and rice. In order to avoid the negative impact from a possible future fall in international prices for food, the Uruguayan economy must quickly change towards products that have more value added and are less dependent on the ups and downs of international price cycles in primary goods.

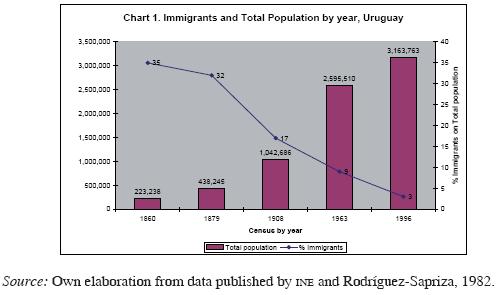

This brief introduction gives an outline of the country's situation, and with this context in mind we will now move on to an analysis of the contributions that immigrants have made. There is a general idea that Uruguay was built by people who 'stepped off the boat'. A census in 1860, thirty years after independence, registered 223,000 inhabitants and one third of these were foreign born; this rate would continue more or less unchanged for thirty more years (Chart 1). We do not have information for 1889 at a national level, but in that year there was a census just in Montevideo, the capital, and it emerged that no less than 47% of the population of this city were foreign born. If we consider only the population over 20 years old, immigrants amounted to the impressive figure of 71% (among males over 20 the total was 78%). We cannot make an exact estimate of what percentage of the whole country's population were immigrants but it is very likely that the figure was as high or higher than in 1879, because studies of that period show that many of the immigrants who landed at the main port, Montevideo, made their way inland to other parts of the country (Rodríguez and Sapriza, 1982). The next census was in 1908 and it showed that although a high figure, 17%, were foreign born, immigration had already decreased sharply, and this falling trend was to continue for the rest of the 20th century.

It is quite clear that 19th century Uruguay was the "product of immigrants", who were incorporated into the country at the same time that they were shaping its nationality (Barrán and Nahum, 1979:103-104). "The time of the greatest economic growth in Uruguay, between 1871 and 1887 when its per capita income was comparable to England, France and Germany, was the time of great demographic growth, product of the avalanche of European immigrants seeking economic prosperity, with an ethos of work and austerity; all values that laid the foundations of our past greatness" (Díaz, 2004). The influence of some of these communities of immigrants has been studied mainly at the economic level, but little has been done from the cultural and sociological perspective (Vidart and Pi Hugarte, 1969). The roots of this cultural invisibility can be traced to the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th, when the Uruguayan national identity was invented and the notions of one nation, one culture and one country were stressed.

This paper will: i) show that, although no large numbers of new immigrants have arrived for more than half a century, today's descendants of previous immigrants have a clear perception of what their grandparents' contribution to the country was; and ii) claim that among immigrants' descendants today there is an ongoing process of rediscovery or reinvention of a "hyphenated identity" which expresses a new demand for recognition and multiculturalism (Taylor, 1993; Kymlicka, 1996; Loobuyck, 2005), that will most likely have some impacts on the traditional Uruguayan identity (Lesser, 1999; Huntington, 2004).

Immigrants' contributions to Uruguay

While it is true that almost no new immigrants have come into the country in recent decades -with the exception of a few thousand Peruvians and Arab Muslims-, some 17% of the population have four foreign-born grandparents, and 46% of the population have at least one foreign-born grandparent (Cifra, 1993). It has also been estimated that today 60% of Uruguayans have a Spanish ancestor and 40% an Italian ancestor. I will briefly explore how several groups in the present population who are descended from immigrants -Africans, Basques, Italians, Swiss, Russians, Jews, Armenians, Lebanese- perceive their immigrant grandparents to have contributed to the building of Uruguay, and how two of the latest immigrant communities -Arab Muslims and Peruvians-feel they are doing so now.2 This section is based on 94 in depth interviews with immigrants or their descendants, and also on the book Multiculturalismo en Uruguay (Arocena and Aguiar, 2007). The interviews were conducted during the year of 2007. Although we used a qualitative methodological approach, the selection of these individuals took into account gender and age diversity. Several interviewees held some kind of representative position (religious, cultural, political, intellectual) but many did not. One of the questions posed to all interviewees was about their perception of which was the main contributions his/her community made to Uruguay. These complete interviews are available in printed and electronic format (Arocena, Aguiar and Porzecanski, 2008).

It is possible to argue that it is incoherent to treat jointly social groups who are defined by such different bonds as race (Afro-uruguayans), nationality (Russians or Lebanese), or religion (Arab Muslims or Jews). Why bring them together? Will Kymlicka's statement could serve as a good argument to do so: "Modern societies have to face more and more minority groups that demand the recognition of their identity and the accommodation of their cultural differences, something that often is labeled as the challenge of 'multiculturalism'" (Kymlicka, 1996:25). These ten groups have in common a set of meaningful cultural traditions that bind them together while distinguishing from others. In our selected cases, these traditions are associated with language, religion, skin color, common history, and/or territory. All of these dimensions simultaneously, or some of them, are a "source of meaning and experience" defining and constructing their "identity" which has "the power" to influence their decisions and courses of action (Castells, 2000:6). So we can consider each one of them as "ethnic groups" with a common history, identity and an awareness of arrival to Uruguay. Which is their perception of their contribution to this country?

Africans

Afro-Uruguayans account for 9% of the total population and they are distributed quite evenly between the capital city and the rest of the country. The first blacks in the country were not immigrants in the strict sense because they were brought as slaves. In the specific case of this ethnic group, their source of meaning is a mixture of "ethno-racial identity" (Cristiano, 2008). If it is true that the concept of race has been discredited after the Second World War when most anthropologists and biologists alike concluded that there are no biological ways of recognizing human races (Wade, 1997), it is also real that skin color is still an important component for this group's identity as well as for the way others see them. Race must be considered a social construction with no biological foundation other than a diffuse perception of skin color, but with a powerful sense of belonging, associated with a past of discrimination, a common African origin, and a shared cultural past and resistance. Afro-Uruguayans were brought as slaves in the 18th century, and for most of their history since that time, even after slavery was abolished, they have not been treated as regular citizens. But in spite of this segregation, they have contributed to building the nation in a number of important ways. Probably their most obvious contribution has been their influence on music through dance, drums and Candombe, a distinctive and very pure African drum rhythm which has become a veritable landmark in Uruguayan music and Carnival. One Afro-Uruguayan who was interviewed put it as follows: "I think that in January and February, at Carnival, we are all the same colour, we are all black. Uruguayans who live in Germany hear Candombe music and immediately they say: 'Oh! That is from home'."

Afro-Uruguayans have also made a big contribution to Tango music, and while this is less well known it is not less important. The word 'tango' has three possible original meanings, and all three have an African root. The first comes from the original African word 'tango' from Angola, which can be translated as "a closed or reserved place"; the second meaning comes from the Portuguese word tanguere, which was introduced into the River Plate by slaves brought in from Brazil; and the third meaning could just be an onomatopoeia for the sound of the drum beat -tan-go- (Collier, 2002). There have been persistent efforts in the Afro community to raise people's awareness of the Afro contribution to the country beyond music or sport. There have been complaints, for example, that history books do not show how in the military campaigns of Uruguay's long fight for independence in the 18th and 19th centuries, Africans were used as cannon fodder in the vanguard of the attack. There have also been complaints that there have been few studies of how blacks contributed significantly as household labor and as workers in the countryside and in the construction industry. They claim that the symbolic national figure of the old gaucho expressed a mixture of natives, blacks and Spaniards. Many common words in use today clearly have African roots: mucama (maid), mondongo (typical food), quilombo (brothel or mess), bujía (electric lamp), catinga (bad smell) and others too numerous to mention. Finally, the Afro influence in religion is also significant because slaves brought Afro cults associated with Umbanda religion to America. In these cults African idols were originally disguised with the names of Catholic Saints so they would not be outlawed. Spirits are incorporated by mediums in trances, and nowadays these rituals are very popular and many people go to the temples seeking favors associated with work, love or health problems. In modern Uruguay, February 2nd is a massively important religious festival on which hundreds of thousands of Uruguayans go to the beaches to celebrate Iemanja's day (Iemanja is the queen of the seas in the Umbanda religion). Of course, only a few of the people that take part are believers in Afro cults, but they still like to watch and participate in a very colorful and picturesque ritual. Current data clearly show that Afro-Uruguayans suffer from serious structural socioeconomic and cultural discrimination, and this, added to the fact that they have always been kept "invisible", has become a major cause for complaint from this community.

Basques

There have been estimations, admittedly not very reliable, that 10% of the Uruguayan population have Basque forebears (and 60% have Spanish forebears of some kind). The Basque presence in Uruguay can be traced as far back as the founding of the capital city in 1726, and the first governor, Mauricio de Zabala, was himself a Basque. So this gives the Basques special importance insofar as they were founding immigrants in an almost empty territory. There have been several waves of Basque immigrants, the last of which was made up of people escaping from the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Basque family names such as Aguirregaray, Ahunchain, Arocena, Bordaberry, Olazabal, and many more are very common in Uruguay and the telephone book is full of them. There have also been historical figures and presidents with Basque surnames. People of Basque descent point out that their community has made contributions in other areas as well. Gastronomy is a special field, for example, because the Basque diet included a lot of vegetables and fish in a country where meat was and still is the basic food. Many words from Euskera (the Basque language) have been incorporated into everyday usage and are heard all the time today, although some with slightly different meanings from the original. For example sucucho (which means 'little corner' in Basque) is used in Uruguay to mean a small and untidy place to live; pilcha (which means 'old cloth' in Basque) is commonly used as slang for clothes; cascarria (which means the dirtiness in the sheep's wool) is used to refer to something very old and in bad shape, or an old car in bad condition. The Basques earned a reputation for effort and dedication to work, and they contributed significantly to the development of the sheep industry in a land where cattle predominated absolutely, and also worked hard in the quarry business. One very special contribution from the Basques, which is not easy to detect in other immigrant communities, has been their capacity to mix with other immigrants. They played the role of helping other immigrants to blend together, acting somehow like a catalyst between different peoples. One Basque-Uruguayan who was interviewed put it like this: "The great contribution from the Basques is something that they did not intend to bring, but it happened. I think they were some kind of a 'paste'. I have the impression that, without meaning to, the Basques became the link, the connection, the blending element between immigrant communities."

We should also note some additional elements associated with Basque idiosyncrasies because it is said these have been passed down to their descendants in Uruguay today: their stubbornness, honesty, solidarity, and constant opposition to anything at all. During most of Uruguay's history there were only two political parties, the Reds and the Whites, and the former governed for most of the time. It is said that when the Basques first arrived in Uruguay they asked what the ruling party was, and when they were told it was the Reds they immediately joined the Whites. And it is true that today most Basques vote for the White party. There is one more contribution that has to be mentioned, the typical Basque blue beret: this is worn by very many people in the countryside as part of their normal outfit, whether they are of Basque descent or not.

Italians

Besides the Basques -and other Spanish immigrants from the Canary Islands, Galicia, and Catalonia- the other immigrants that are regarded as having been involved in founding the country are the Italians, and today some 40% of Uruguayans have Italians among their forebears. This group arrived in huge numbers in the 19th century and they continued to come until the Second World War. The great hero of Italy's independence and unification, Giusseppe Garibaldi, lived in Montevideo and was involved in the civil war after Uruguay became independent, fighting on the seas for the Red political party. Garibaldi is still honored by this party as a war hero. But Italian political influence went much further because, at the end of 19th century and the beginning of 20th, thousands of Italians who had been politically active in their own country in labor unions and as anarchist militants, arrived and made a big impact on Uruguayan politics and the labor movement. As a direct consequence, Uruguay was the first country in Latin America to legally establish the eight hour working day and to accept labor unions. Italian influence is also very visible in the architecture of Montevideo, where the Congress building and most of the fine buildings were constructed in the 19th century Italian style. In the wake of massive immigration from that country, a new kind of association was developed to provide social and economic protection for all the newcomers. Italians set up the first mutual health care institutions, and the private health system in the country today was shaped by this model. Other Italian contributions are the extended family with strong kinship ties, the use of words of Italian origin, and, until 2006, the obligatory teaching of Italian in lay secondary education. And of course local gastronomy was also influenced: we have the traditional pizza, and also faina (made of chick-pea flour) and polenta (hot or fried cornmeal cooked in the Italian style). A very recent and original contribution is the Italian Patronatos, which are institutions funded directly from Italy geared to reestablishing contact with Italian migrants around the world. A director of one of these institutions explained why this initiative is taking place:

There is now a new Italian offensive -to give it a name- in relation to their Diaspora. Now that Italy has solved its own economic problems, the authorities want to regain contact with their communities overseas. In Uruguay there are 7,000 Italians who were born in Italy but 100,000 Italians who were born in Uruguay.

These Uruguayan-born Italians are the children of immigrants, and they have been applying on a massive scale to obtain Italian passports and nationality because this gives them the chance to migrate to Europe and, under European Union regulations, they are allowed to work not only in Italy but in other European countries too. Things have come full circle.

Swiss

Switzerland was not always as rich as it is today. In the mid 19th century it was plunged into severe economic crisis due to the great impact that the industrial revolution had in rural areas, putting thousands of peasants out of work. Besides this, at that time Switzerland passed a law whereby mercenaries were outlawed. Thousands of Swiss who were paid soldiers outside the country had to return and join the unemployed. In this scenario many decided to move abroad and some reached Uruguay. In 1862 they founded an agrarian colony in the South called Nueva Helvecia (Helvetia is the Latin word for Switzerland) and by 1878 they totalled some 1,500. Today this city has 10,000 inhabitants, although not all are of Swiss descent. Of course, their main contribution to Uruguay stems from the fact that they originally formed an agrarian colony. A Uruguayan of Swiss descent has very clear ideas about this: "To introduce agriculture here in the 19th century was a real innovation. Land cultivation didn't exist... They also innovated by introducing the cheese industry... This has marked the area of Colonia and we are still known today as the cheese makers."

There were other contributions too, such as houses with four-sided roofs, which did not previously exist in the area, and many innovations in the production of conserves, sausages, and beer. These traditions were transplanted from a cold weather climate where it was necessary to stock food to survive the long and cruel winters, which is something Uruguay does not have. And Swiss immigration also brought with it a mentality of doing things well, of quality, and this is still a feature of the excellent artisans in that area and the good standard of work done by electricians and metal workers there. This new way of doing things was also apparent in the immigrants' social organization, which was based on a strong sense of participation and a network of institutions maintained by the community. At the root of this horizontal community-building was Protestantism, which was first introduced into Uruguay by Swiss immigrants. And today, one and a half centuries after these people settled in Nueva Helvecia, the city is still neater and tidier than other towns in the area, many houses display family shields from original Swiss locations, there is greater prosperity, there are much higher rates of Protestants, and there is a thriving milk industry which even has its own technical and educational institutions. Every year, in the first week of December, the city celebrates its foundation with what is called The Bierfest, and thousands of Uruguayans come to participate in wood cutting competitions, beer drinking races or traditional dances.

Russians

Russian immigration came fifty years after the Swiss, but it had more or less the same objectives as these people also came to establish an agrarian colony, which they called San Javier. It should be noted that the Uruguayan government at that time was operating an immigration policy to attract colonists to the countryside, which was empty and lacked agriculture. The two colonies were similar, but the reasons why these people emigrated in the first place were completely different: the Russians were not escaping from economic problems but pursuing religious freedom. They had formed a sect called New Israel that was persecuted in Russia, which was already on the verge of revolution. In 1913, some 300 families came to Uruguay and quickly settled on land that was donated to them free of charge. They quickly made a significant impact; they built one of the first oil mills of the country, they built a flour mill and they started a honey industry. But their emblematic contribution was to introduce the sunflower, which had never been seen or known in the country before they arrived. One descendant of those immigrants remembers that: "When the first yellow sunflowers bloomed, the locals were completely astonished and they could not believe their eyes. They said: 'these Russians must be completely crazy, they brought their own flowers and planted a whole field just with yellow flowers!'"

With the new crops some unusual gastronomy developed in the colony, partly based on cheap vegetables (that were high in calories) from a cold climate. Not surprisingly, some of the colonists later adopted political trends from their motherland. A very striking political symbol can be found today in the cemetery: there is a tomb with the name Julia Scorina, who was a political activist shot dead by the police in the thirties, and it is painted completely red and has the communist symbol of the hammer and sickle in yellow. In San Javier there is an active political club named after her. In 1984, during the dictatorship, the small town was front page news when one of the inhabitants, a physician called Vladimir Roslik, was tortured to death accused of having contacts with Russian Communists and receiving arms and ammunition, which was all completely false. Like in Nueva Helvecia, every year San Javier celebrates its foundation with a tremendous party at the local theatre, which is called Maxim Gorki, in honor of the Russian screenwriter. People from the immediate area come into town, which now has a stable population of a couple of thousand, but representatives of local and national authorities and Russian diplomats and Russians living in the capital city also come to celebrate. They adore eating the special Russian food such as shaslik (made of lamb, onion, and moscada nuts mixed together for twelve hours) and piroj (bread with cabbage jam filling), and they drink kvas (a beverage made of fermented honey and water) and watch traditional dances performed by the local group Kalinka.

Jews

There are 20,000 Uruguayan Jews and they amount to 0.8% of the total population. Some decades ago there were considerably more, but many migrated to Israel to get away from long term economic stagnation in Uruguay, and no new immigrants arrived. During the last thirty years, approximately 10,000 Jews left Uruguay, the majority en route to Israel. The first Jewish immigrants came to Uruguay at the end of the 19th century from Eastern Europe; they were Ashkenazim from Poland, Rumania, Russia, Hungary and Lithuania. The second wave came from the Mediterranean area and North Africa, and they were Sephardim. There was also a third wave of approximately 10,000 Jews escaping from Nazi Germany who came to Uruguay between 1933 and 1941. Among the first Jews there were small shop-owners, tailors, artisans who worked with precious stones or gold, and merchants who sold haberdashery products. Many of these people introduced innovations in how business was done in the country, like payment in installments (hire purchase). A Uruguayan-Jew put it this way:

hey went door to door offering blankets they carried on their shoulders and baskets with all sort of cloth and linen products and they left them with the woman or the man of the house without any payment, and they would say: 'This costs 80 pesos and you can pay me over ten months at 10 pesos a month'. The Jews were also the first to create a debtor registration system. They wrote in chalk on the house door of the debtor the first letter of the Yiddish word tshvok, which means nail, so when another Jew came he knew already.

The Jews have also made their own characteristic contribution in that they have actively participated in the intellectual life of the country as artists, painters and writers. Some became quite famous, such as Gurvich (a painter) or Rosenkof (a writer). This strong Jewish influence in Uruguayan intellectual life is not unique to this country as Jews have been influential in these fields in other countries as well. This is consistent with the fact that they assign great importance to formal education and consider it a vital element in their economic well being. Many of the first generations that landed came with little or no capital, but hard work and persistent and continuous investment in the education of their children yielded rich returns. Most Jews have been upwardly mobile in society and today almost all of them have moved from the humble neighborhoods where they first lived to middle or high socioeconomic districts in the capital city. They have above-average social indicators with more years of education, better economic performance and greater well being. They also have a closely-knit network of social and sports institutions and their own educational institutes, and today there is even a website to help Jews to find a Jewish girlfriend or boyfriend, which is called Cupido Jai. They have fully integrated into Uruguayan society and they participate in all its dimensions and this includes politics: Jewish candidates are regularly elected as senators or representatives in parliament. But in spite of this, most of the members of this community who were interviewed stated that at some point in their lives they had suffered discrimination for being Jews.

Armenians

Like the Jews, the Armenians arrived at the end of 19th century and the start of the 20th. They were fleeing from persecution in the Ottoman Empire, first from Sultan Abdul Hamid, the "Red Sultan", and then from the final genocide that took place in 1915 under the government of the so called "Young Turks". In 1965 Uruguay publicly recognized that Armenians had been massacred, and it was the first country in the world to do this, although it did not actually use the word 'genocide'. Those events were the main cause of the Armenian diaspora around the world. Armenians are particularly grateful to Uruguay for this gesture of recognition, and this is why the country is quite well known among Armenians everywhere. At the time of the massacres some six thousand Armenians came to Uruguay and now the community has grown to sixteen thousand. The early arrivals dedicated themselves completely to working for their new country and they made every effort to help this new land develop. One Armenian-Uruguayan who was interviewed said that:

Our biggest contribution was people that came to work. In 1915 the law that established the limit of 8 hours of work per day was passed, and a few years later the Armenians arrived and they worked exactly twice that amount. The invisible work we did in factories, slaughterhouses, industries, every day - that was our great contribution.

The story of the Armenians in Uruguay is somewhat similar to that of the Jews in that both groups have integrated successfully and now enjoy good socioeconomic indicators. The Armenians entered different areas of society, first working in the slaughterhouses, then as merchants, professionals or academics, but they also feature in sports and soccer (the national game), and in politics. The Armenian community is divided in two. This is due to conflicts stemming from the Soviet Union conquering the independent State of Armenia in 1920. One part of the community supported the Soviet regime because it served as a defense against the Turks, and the other half opposed the Soviet conquest of the young Armenian State, which had only come into being in 1918. The Armenians in Uruguay do not just work hard, they have also generated an important ethnic food tradition including the popular lehme-yun (or lahmajoon), a meat pie that is also called Armenian pizza. They have been outstanding in some games such as chess and some sports like Greco-Roman wrestling. They own two prestigious educational institutions, and two radio stations that have been in operation for 70 years and broadcast daily news of specific interest to the Armenian community as well as mainstream music or other general programs. Today last names ending in "-ian" are a normal feature of Uruguayan society; to mention just three examples we have Lilián Kechi-chian - the Vice Minister of Tourism, Abraham Yeladian - a first division soccer coach, and Rubén Aprahamian - a very popular shop owner.

Lebanese

Lebanese immigrants arrived at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. Their children and grandchildren now amount to almost 1.5% of the total population, approximately 50,000 people. They came seeking better economic conditions, but some years after many had settled in Uruguay there was a new Migration Law, passed in 1890, in which it was laid down that "immigrants from Asia, Africa and individuals known as gypsies or bohemians" should be banned from entering the country if they came with a second or third class ship ticket". The Lebanese living in Montevideo contested this Law arguing that even though they came from Asia they were not "inferior races" like the "yellows" or "blacks" which the Law was designed to stop, and that Lebanese were allowed to enter the U.S.A. while Chinese people were barred. They made their point and the government removed them from the list of "unwanted immigrants" (Acerenza, 2004; Supervielle, 1989). Of course, that old racist law was later abolished, and now there are almost no restrictions on immigration into Uruguay, although it is still difficult to get through all the red tape. One of main Lebanese contributions to Uruguay was to bring trade to almost inaccessible places in the countryside. A Uruguayan-Lebanese remembers the story of his grandfather:

The first Lebanese, like my grandfather, took trade to the countryside. They reshaped commerce in Uruguay, walking along deserted tracks with their 'Turk-trunks' loaded with merchandise that they sold to the gauchos on the farms. They also introduced credit. Our main national roads are named in memory of national heroes, but the small secondary roads should be named after those first Lebanese that walked them for so long.

After that first stage, many of these merchants settled down in small towns or villages and developed prosperous businesses that sold a wide variety of merchandise, and these shops were passed on to subsequent generations. In the beginning the Lebanese were called "Turks" because that was the language they spoke (even the Armenians were generally known as Turks at first, for the same reason) and they resented this as a kind of discrimination. Today people of Lebanese descent are still called that but now it is meant in a friendly way (this does not apply to the Armenians). The Lebanese have made a lot of positive contributions to the country and the best known include family values, honesty and dedication to work. They have set up numerous institutions and two in particular stand out as they represent a strong bond among this group. First there is the Maronite Mission, which is recognized as their fundamental religious institution because the vast majority of these immigrants were Christian Maronites. Second there is the Lebanese Embassy, which acts as a sort of nexus with the political reality of the Lebanon. Recently many Uruguayan-Lebanese have traveled back to the Lebanon in search of other family members who stayed behind. These trips mean that relatives who have never seen each other can become acquainted. People from the Lebanon have also come to Uruguay, and now there is growing communication between the two countries as Lebanese living in their motherland have got to know the country of their Uruguayan relatives.

Arab Muslims

This is a small group, around 500, and they settled in two small border towns where the international boundary itself is just a street, Rivera and Chuy, which are half Brazilian half Uruguayan. While the Arab Muslims are few in number they are very conspicuous because they own many shops and supermarkets and they are active merchants. Women are often seen in the streets dressed in their traditional Muslim costume and some wear the veil to cover the face. Men too wear Muslim style outfits. It is very common to hear people talking in Arabic or see them watching Arab programs or news on the TV in their businesses. They have a mosque and are allowed to bury their dead directly in the earth wrapped in a white sheet. Most of them came originally from Palestine and they are already third generation as they came in the sixties, although today younger people are still arriving. They live in accordance with their own mores; polygamy for men is accepted although it is not practiced because it is forbidden by Uruguayan law, and in the family the patriarch has authority over the women, who are obliged to cover their bodies and are not allowed to pray with the men. They maintain close connections with Palestine, and all its political vicissitudes, and indeed everything going on in the entire Muslim region, are followed with great interest. After September 11th, shots and shouts of joy were heard, when Arafat died in 2004 shops were closed in homage to their leader, and in 2006 when the Lebanon was attacked by Israel there was a huge street demonstration calling for peace. The CIA and the Israeli intelligence services keep a close eye on this community, which they consider could be a haven for Al Qaeda terrorists. In 1999, a certain Al Said Hassan Mokhless was detained in the city of Chuy with a false passport, and accused by Egypt of terrorism and of training recruits for the Hezbollah group. The Arabs complain that they have been stigmatized as potential terrorists in spite of the fact that there has never been a single episode that proves any link with known terrorists. This stigma has given the community a strong sense of awareness and paranoia, and this was felt directly by two students who were doing interviews as part of our research. They were mistakenly thought to be working for the Israeli secret service. Community leaders complain about this stigmatization and emphasize that they have settled peacefully in a border city because they are merchants and are dedicated to working and developing trade in the area. The official spokesman for the community says it clearly:

I came by chance because I had a cousin living here who asked me to work with him, things were not so good back home in Jerusalem so I came... it is just the same as Uruguayans that go to the US or Australia to get a better quality of life.. .The majority come to work in trade, but we also have people who own hotels, restaurants.We want to work and make a little money... We almost don't have free time, we work every day and only close on Sunday afternoons.

Peruvians

This is the most recent group of immigrants. They started arriving at the beginning of the 1990s, which was a time of serious economic depression in Peru under the dictatorship of Fujimori, and there was guerrilla warfare involving the Shining Path. According to the most recent census in 1996 there were 576 Peruvians in Uruguay, and now there are between 2,500 and 3,000. They have inserted into two labor areas; men have found work on fishing boats and women in domestic service. They came seeking better pay, and part of their income is sent back as remittances to their families at home. Some come in transit so to speak, and they only stay long enough to earn the money to finance a move on to Spain. The Peruvians are a small immigrant group, they have arrived after fifty years in which Uruguay received almost no immigration, so they have been an interesting challenge to the Uruguayan tolerance of immigrants. They stand out for various reasons: first, because they were competing for jobs in an economy that was far from booming; second, because their Andean physical appearance makes them very visible and different; third, because they "took over" some places in the old neighborhood of the city with their night clubs -one that became very famous was called Machu Picchu-, with ethnic restaurants, or just with their presence in public plazas waiting to be called for jobs on ships and boats. There was a reaction against them, and sometimes this was quite aggressive. Graffiti appeared telling them to go home or calling them traitors because they would work for lower wages than local fishermen and would not join the labor union. On several occasions the houses where they lived were defaced with paint on the front door or walls, and they were threatened or challenged to fights. The Peruvians wisely did not react to this provocation, and now they are left in peace and have become familiar figures in the urban landscape. According to one Peruvian immigrant:

I would say that our biggest contribution to Uruguayan society is solidarity. The second is that we never surrender and always look forward; we are also more go getters. And the third is joy, we laugh much more, we have more parties. These are the things we are contributing: solidarity, decisiveness and happiness.

It is important to note that the briefness of this paper might entail the risk of oversimplification and stigmatization of ethnic groups, which are indeed complex and heterogeneous when looked with a finer lens. In this paper I tried to focus more on their significant contributions to Uruguay, based on the group's perceptions. Sometimes I have highlighted a contribution because it appears to be very pervasive among all the members of that community, but in other cases I have singled out some contribution because of its innovative power. I chose to leave aside a more structural analysis, which would have looked at the economic and political integration of each group to the country. Readers interested in these topics can find more in-depth discussions in Arocena and Aguiar, 2007.

Immigration, Transnationalism and Multiculturalism

Immigration studies gained a new momentum in social sciences due to at least two different reasons. The first one has to do with the extraordinary increase in the amount of people currently living outside their country of birth. According to CEPAL (2006), 200 million people live outside their homelands, number which in Latin America is as high as 26 millions (Vono, 2006) and in Uruguay is 600 hundred thousand, 20% of its actual population (Pellegrino and Koolhaas, 2008). The second reason is that these new waves of migrants integrate to the countries of arrival in a different way than migrants did in the past, and, at the same time, develop new types of bonds with their country of origin. The theoretical approach that puts forward these differences is closely associated with the notion of transna-tionalism, through which migration "should be understood as part of two or more interconnected and dynamic worlds" and as a process "sustained by multi stranded social relations that bring together both, societies of origin and arrival" (Vono, 2006:12; Levitt and Nyberg-Sorensen, 2004). This process gives place to what has been called a "transnational space" (Portes, 2005) in which "trans-migrants" live at the same time in this new social context but intersected by different cultures. The concept of transnationalism emerged in part as a response to the specificities of the recent waves of Latin American migration to the United States and previous European migration at the end of 19th and beginning of the 20th century. A crucial difference was that these new immigrants do not follow the traditional assimilation path, through which old immigrants tried to completely adopt the North American way of life: "assimilation as the American Style" (Salins, 1997). According to this classic assimilation theory, immigrants that arrived to America tried as quickly as they could to assimilate to the American way of life: learned and adopted English language, felt pride in American identity, and believed in the Protestant ethics creed of hard working, savings and strict morality. Through this assimilation process millions of immigrants were "Americanized" as the prerequisite to be integrated to American society. First generations started with this conversion, which was fully completed by the second generation (Huntington, 2004:218). More recent Latin American immigrants and their descendants, who amount to almost 45 million people living in the United States (half Mexicans or Mexican descendants), changed completely this trend. After three decades of massive arrival, assimilation theories had to be rethought because what happened is that this new migrants integrate in a different way: they do not abandon their mother language, they maintain a frequent relationship with their country of departure, and they do not want to become completely Americanized, even if many identify themselves as North Americans. These new migrants developed a double or hyphenated identity with strong bonds to both countries, and in this process they changed the United States with their contribution (for some critics, instead, pollution), and they are also impacting on their countries of origin through, for example, economic remittances, traveling, or just by regular communications in a transnational space.

If this new type of immigration gave origin to the theoretical approach of transnationalism in the United States, also immigration has played a crucial role in the theory of multiculturalism, developed in Canada by Taylor (1993) and Kymlicka (1996). Theories of multiculturalism and transnationalism are not linked together as much as they should when dealing with immigration issues in different contexts, but it seems quite clear that they address very similar social problems. It is true that multicultu-ralism in Canada can also be traced as a solution to the pacific coexistence between the native population, the French, and the English descendants. But by no means we can put aside the impact that immigration had in this country, labeled as "the most immigrant of western nations" (Haroon Siddiqui, in Stein, 2007: 45). To put it shortly: 6.2 million immigrants live nowadays in Canada, which represent 20% of its total population, and this proportion jumps to 46% in the city of Toronto and to 40% in Vancouver. Immigration and historical roots pushed to the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1985, its own solution to achieve pacific integration of minorities and immigration. The Act establishes that: "persons belonging to ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities shall not be denied the right to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion or to use their own language". This is the basis of multiculturalism, the recognition that a group of people has the right to its own culture, when it is not in contradiction with the expansion of individual freedom of its members to choose among several options (Sen, 2006).

Transnationalism and multiculturalism have, of course, its critics. For example, for Samuel Huntington, one of the most radical voices against Latin American immigration in the United States, the decay of the old assimilation process means the end of the United States as it was and as he wanted it (one nation, one language, one culture). From his point of view it is also negative for a citizen to have two nationalities, because this legitimizes a hyphenated identity and dual loyalties, which are weaker and not enough to support the country where they are living. There are also in Canada many antagonists to multiculturalism that blame immigrants for low economic performance, violence, insecurity, lack of pride in Canada, self segregation and "unassimilable or unwilling to do what they must to integrate", while criticizing the government for not forcing them "to become fully Canadians" (Siddiqui, 2007) . In spite of these critics "multiculturalism in Canada is a fact, a policy and an ethos" (Kymlicka, in Stein, 2007:140). It is a fact because of the ethnic diversity of its society, it is a policy because ethnic rights are granted by the constitution and several programs have been put in practice for this, and finally it is an ethos because Canadians deal with diversity with this framework.

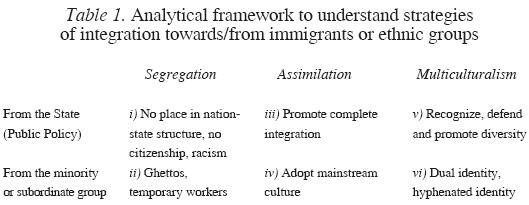

The terms assimilation and multiculturalism (Huntington, 2004; Taylor, 1993; Kymlicka, 1996; UNDP, 2004; Loobuyck, 2005; Galli, 2006; Sen, 2006; Stein, 2007; Arocena, 2008) could be used to describe two different integration strategies followed by -or adopted towards- minority or subordinate ethnic groups. The strategy of assimilation is a process of integration whereby immigrants adopt as much as possible of the dominant culture -language, education, clothes, religiosity, or family relations-. Assimilation can be a State strategy, a public policy, whereby different groups are forced or persuaded with specific benefits to adopt the dominant culture. But it can also be a strategy employed by the groups themselves, if they are convinced that it is the best way to integrate. On the other hand there is the strategy of multiculturalism, which differs from assimilation in that the groups will try to integrate into society but maintain as much as they can of their own culture. This typically involves building hyphenated identities, which express their having two national heritages at the same time. Again, multiculturalism can be a strategy employed by the State, in which case cultural diversity must be granted, protected and recognized. But the community in question can itself adopt this strategy. There is still a third kind of "integration", which is neither assimilation nor mul-ticulturalism, and this is segregation. This pertains when an ethnic or immigrant community lives in the middle of another people but is as isolated as possible and makes no effort to learn the new language or create ties with the general population. This is what happens with ghettos. Of course, the state too can employ segregation as a strategy towards an ethnic or immigrant groups that are not welcome. These six analytical possibilities are summarized in Table 1 below:

It would be useful to mention at least one well-known example for each of these possibilities. A good example of the first case is the Jim Crow laws and the segregation policy towards Negroes in the United States before the civil rights revolution of the sixties. Muslim immigrants in some European countries exemplify the second case, for example in Sweden, where these people commonly form ghettos or cultural islands. An example of the third situation in this analytical framework might be the traditional French policy of assimilation towards Muslims in which universal citizenship is given priority over the rights of particular communities. The fourth case is well exemplified by the strategy followed by Italians in Brazil and the United States when they arrived at the end of the 19th century and start of the 20th: they wanted to become undifferentiated members of these national populations as quickly as possible. A good example of the fifth case is Britain's multicultural policy towards Pakistanis since the eighties, or better still Canada's 1985 Multiculturalism Act. Finally, the sixth scenario can be exemplified by the Hispanic strategy of keeping their Latin American identity while adopting North American ways and becoming Mexican-Americans. Another example here would be members of the black community in the U.S.A. redefining themselves as Afro-Americans.

Conclusions: A shift towards multiculturalism in Uruguayan immigrant descendants

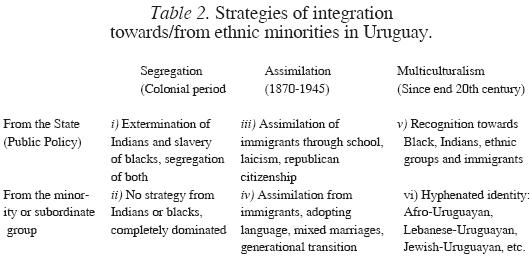

There is still one more general contribution to Uruguay from immigrant and African descendants that I shall try to analyze before closing this paper, and it has to do with what is happening at present with some of these communities and the way they can reshape the Uruguayan identity. I will call this phenomenon the shift from assimilation to multiculturalism. We can now return to Uruguay, and by incorporating a time line into our previous analytical framework, we can understand different integration strategies that have developed during the country's history (Table 2).

Each one of the six cells of the previous table can be explained briefly: i) After Uruguay won her independence in 1830, the State's strategy towards indigenous people and blacks was extermination or segregation, but under no circumstances was it to consider these groups as part of the Uruguayan nation or as people shaping the country's identity. ii) These ethnic groups had no strategy of their own because they were extremely weak and helpless in the face of the central power of the State. But there was a good example of segregation that developed within an immigrant community, namely the Swiss: when they founded Nueva Helvecia they forbade all contact with the locals during the early years of the colony. iii) In the period of the greatest influx of immigrants, which included the important watershed of the Batlle y Ordonez government and continued until the Second World War, the State's strategy was to assimilate immigrant groups. This policy was mainly implemented through state schools, the universal use of the Spanish language, laicism, and a number of other stimuli to dilute differences and create one homogenous nation. iv) The various communities themselves also opted for assimilation as the quickest solution to alleviating the traumas of their transition to the different world they had arrived in. A major factor in this assimilation process was mixed marriages, with male and female immigrants marrying Uruguayans. v) It is not until the 21st century that the Uruguayan State started to adopt multiculturalism as a strategy towards people of indigenous or African descent. This shift in strategy came about as a consequence of what is happening in neighboring countries in the region. There are now new policies to promote cultural diversity and to recognize these groups as protagonists in a shared history who have contributed to shaping the national identity. The traditional way of understanding the country as one nation, one culture and one language is yielding, and a more diverse national identity is under construction. Antidiscrimination legislation in Uruguay has been passed in 2004 with the approval of the Law 17.817: "Fight Against Racism, Discrimination and Xenophobia", although there is still a long way to go in this direction. Explicitly the law mentions discrimination based on "race, skin color, religion, national or ethnic origin" (Article 2), among other posssible sources. Also more recently Uruguayan Congress, addressing the new contemporary immigration context, approved the "Immigration Law 18.250" in January 2008 in which it is established that: "The State will respect the cultural identity of immigrants and their families and will foment that they maintain their bond with their country of origin" (Article 14). vi) In the last decade some of these communities have adopted a multicultural strategy, re-asserting their own cultural traditions and defining themselves more and more with a hyphenated identity. What theories of transnationalism and multiculturalism have found for recent immigration waves, as mentioned in the cases of the United States and Canada, is also currently permeating descendants of old immigrants in Uruguay. Descendants of Italians and Basques are now seeking double nationality and tens of thousands of them have migrated back to the countries from where their parents or grandparents departed. It is easy to recognize the transnational space that has been created between these descendants in Uruguay and the two countries, also fueled by the bonds developed from recent Uruguayan migrants in Spain and Italy. A similar situation can be found in the Jewish community, from which thousands have emigrated from Uruguay to Israel in the past decades of economic crisis. Lebanese and Armenian descendants do not migrate back to their country of origin, because there is no economic incentive as Armenia and Lebanon are very poor, and even present Armenia is not the land from where first immigrants came. But these communities in Uruguay have strengthened their bond to the countries of their ancestors as never before, either by traveling or by being in permanent contact through the media. Russian and Swiss descendants have a weaker bond to their countries of origin, but in the cities where they are concentrated it is easy to perceive an ethnic revival of their traditional symbols and culture. Peruvians and Muslims are different cases because they are recent immigrants in Uruguay, and it is quite clear that they follow a process of integration to Uruguayan society not through complete assimilation but through multiculturalism, and the premises of transnationalism theory fit to them as a glove.

So Uruguay is an interesting case to study immigrant contributions, but not because it is now receiving large numbers of them: on the contrary, very few have come since the end of Second World War. But on the other hand, in the past the country received some of the most vigorous flows of immigrants ever known, and between 1860 and 1900 newcomers amounted to one third of its population. This period of massive immigration was followed by a period of almost no immigration at all. This means we can discern what the long-term impact of immigration has been because many of their descendants -their children, grandchildren and great grandchildren- still have a very clear idea of how their forebears helped to shape this country.

References

Achugar, Hugo (2005). "Veinte largos años. De una cultura nacional a un país fragmentado", in 20 años de democracia, Taurus, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Arocena, Felipe, and Sebastián Aguiar (eds.) (2007). Multiculturalismo en Uruguay, Trilce, Montevideo. [ Links ]

----------, (2008). "Multiculturalism in Brazil, Bolivia and Peru", in Race and Class. A Journal on Racism, Empire and Globalisation, vol. 49, no. 4, Sage Publications, Institute of Race Relations, London. [ Links ]

----------, S. Aguiar , and R. Porzecanski (eds.) (2008). Multiculturalismo en Uruguay. Entrevistas, vol. 1 and vol. 2, Documento de Trabajo, FCS, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Altamiranda, Juan José (2004). Afrodescendientes y política en Uruguay, monografía, Licenciatura de Ciencia Política, FCS, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Azcona, J. M., and F. Murru (1996). Historia de la inmigración vasca al Uruguay en el siglo XX, MEC, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Barrios, C and O. Mazzolini (2002). "Lengua, cultura e identidad: los italianos en el Uruguay actual", Centro de Estudios Italianos de la U de la R, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Betancur, A., A. Borucki, and A. Frega (2004). Estudios sobre la cultura afro-rioplatense. Historia y presente, F. H. y C., Montevideo. [ Links ]

Borja, Jordi, and Manuel Castells (1997). "La ciudad multicultural", La Factoría, no. 2. http://www.lafactoriaweb.com/articulos/borjcas2.htm. [ Links ]

Brooks, David (2007). "The Next Culture War", The New York Times, June 12. [ Links ]

Bucheli, Marisa, and Wanda Cabella (2007). Perfil demográfico y socioeconómico de la población uruguaya según su ascendencia racial, INE-PNUD, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel (2000). The Power of Identity, Blackwell, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe) (2006). Cuatro temas centrales en torno a la migración internacional, derechos humanos y desarrollo (LC/L.2490), Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Cifra (1993). El País, October 10th and November 14th, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Collier, Simon (2002). "The Birth of Tango", in The Argentina Reader, Duke University Press, Durham. [ Links ]

Corredora, K (1989). Inmigración italiana en el Uruguay (18601920), Proyección, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Cristiano, Juan (2008). "Raíces africanas en Uruguay. Un estudio sobre la identidad afro-uruguaya", monografía de grado, FCS, U de la R, Montevideo. [ Links ]

De los Campos, Hugo, and Laura Paulo (2001). "La población migrante en Montevideo procedente de cinco países latinoamericanos", manuscript, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Díaz, Ramón (2004). El Observador, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Douredjián, A., and D. Karamanoukián (1993). La inmigración armenia en Uruguay, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Galli, Carlo (ed.) (2006). Multiculturalismo. Ideologías y desafíos, Ediciones Nueva Visión, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Gigou, Nicolás L. (2006). "¿Cómo hacer una cartografía del tiempo y la memoria?", in http://www.unesco.org.uy/shs/docspdf/amiario2006/art_08.pdf. [ Links ]

Gil Calvo, Enrique (2002). "Convivencia de culturas", El País, Madrid, 4 December. [ Links ]

Huntington, Samuel (2004). Who Are We: The Challenges to America's National Identity, Simon & Schuster, New York. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (1998). Módulo Raza de la Encuesta Continua de Hogares.http://www.ine.gub.uy/biblioteca/raza/MODULO_RAZA.pdf. [ Links ]

Karp, David (1996). "Los judíos en Montevideo a lo largo del siglo XX". http://dmkarp.es.tripod.com/DavidMKarp/id20.html. [ Links ]

Kerouglian, P. G. (1984). "Apuntes sobre el proceso inmigratorio armenio al Uruguay, in Hoy es Historia, no. 3, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Kymlicka, Will (1996). Ciudadanía multicultural, Paidós, Barcelona. [ Links ]

Lesser, Jeffrey (1999). Negotiating National Identity. Immigrants, Minorities and the Struggle for Ethnicity in Brazil, Duke University Press, Durham. [ Links ]

Levitt, Peggy, and N. Nyberg-8orensen (2004). "The Transnational Turn in Migration Studies" [on line], Global Migration Perspectives, no. 6, Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM). http://www.transnational-studies.org/pdfs/global_migration_persp.pdf. [ Links ]

Loobuyck, Patrick (2005). "Liberal Multiculturalism", in Ethnicities, London. [ Links ]

Mandressi, Rafael (1993). "Inmigración y transculturación. Breve crítica del Uruguay endogàmico", in Uruguay hacia el siglo XXI, Trilce, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Marenales Rossi, M., and J. c. Luzuriaga (1990). "Vascos en el Uruguay", in Nuestras Raíces, no. 4, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Moreira, Omar (1994). Y nació un pueblo: Nueva Helvecia, Prisma, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Oddone, J. A (1968). La inmigración y el desarrollo económico-social, Eudeba, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Pi Hugarte, Renzo (2004-2005). "Asimilación cultural de los siriolibaneses y sus descendientes en Uruguay", in Antropología Social y Cultural. Anuario 2004-2005, Montevideo, F. H. y C.-Unesco. [ Links ]

----------, (1992). "Cajón de turco: apuntes culturales de los libaneses en el Uruguay", in Revista del Cincuentenario del Club Libanés del Uruguay, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Pellegrino, Adela, and Martín Koolhaas (2008). "Migración internacional: los hogares de los emigrantes", in C. Varela (coord.), Demografía de una sociedad en transición: la población uruguaya a inicios del siglo XXI, pp. 115-143, Trilce, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro (2005), "Convergencias teóricas y evidencias empíricas en el estudio del transnacionalismo de los inmigrantes", Revista Migración y Desarrollo, Zacatecas, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Mexico. [ Links ]

Porzecanski, Rafael (2006). El Uruguay judío, Trilce, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Puigrós, Medina, and U. R. Vega Castillos (1991). La inmigración española en el Uruguay. Catalanes, gallegos y vascos, Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Villamil, S., and G. Sapriza (1982). La inmigración europea en el Uruguay - Los italianos, Banda Oriental, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Salins, Peter (1997). Assimilation, American Style, Basic Books, New York. [ Links ]

Sen, Amartya (2006). "Multiculturalism and freedom", in Identity and Violence, Penguin Books, London. [ Links ]

Stein, Janice (2007). Uneasy Partners. Multiculturalism and Rights in Canada, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Canada. [ Links ]

Supervielle, Marcos (1989). "Recuento histórico de las políticas migratorias en el país y propuestas de nuevas políticas", in Cuadernos de la Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales II(11), Montevideo. [ Links ]

Taylor, Charles (1993). El multiculturalismo y "la política del reconocimiento", Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico. [ Links ]

UNDP (2004). Cultural Liberty in Today's Diverse World. Human Development Index. [ Links ]

Vidart, Daniel, and Renzo Pi Hugarte (1969). "El legado de los inmigrantes", Nuestra Tierra, no. 29 and 30, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Vono, Daniela (2006). Vinculación de los emigrados latinoamericanos y caribeños con su país de origen: transnacionalismo y políticas públicas, CEPAL, Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Wade, Peter (1997). Race and Ethnicity in Latin America, Pluto Pres, U.S.A. [ Links ]

Wirth, Juan Carlos (1984). Génesis de la colonia agrícola Nueva Helvecia, MEC, Montevideo. [ Links ]

Zizek, S., and F. Jameson (1997). Estudios culturales. Reflexiones sobre el multiculturalismo, Paidós, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

1 The author would like to thank to CSIC, Uruguay, for a research grant, and to Valeria Brito for her valuable assistance. This paper also benefited from comments at the 38th IIS World Congress in Budapest, 2008, and with the constructive suggestions of two anonymous reviewers when it was presented for publication.

2 There are other immigrant communities which would be also relevant to study, such as the British, the French, the immigrants from Canary Islands, from Galicia or Catalonia, or even the immigrants from some Eastern European countries such as Hungary, Poland or Lithuania. Limits of resources and time made it impossible to extend the research to these other groups.