Table of Contents

I. Introduction

II. Who is a Legal Researcher?

-

III. The Mexican Legal Education System

-

IV. Mexican Legal Research

-

V. Is Legal Research Remunerated in Mexico?

-

VI. SNI

-

VII. Centralization

-

VIII. Are Mexican Legal Scholars Migrating?

IX. Mexico City or Bust: Conclusions

I. Introduction

Legal science is spurned (along with other social sciences) as a resolver of “the great problems of the State”.1 Around the world, scientific research receives little public financing. On average, governments spent 2.3%2 of their gross domestic product on research and development in 2017. The lack of financial support to legal researchers often means that they must secure two jobs to cover their basic needs and, hopefully, obtain the capital needed to fund their research. The impact of not being able to do full-time research poses the risk of lowering the quality of their work or abandoning the project altogether. Moreover, low national employment rates lead graduates to seek work in activities that are not related to their degree which, according to Becerra Ramirez, can be considered a type of “brain drain”.3

This article is an effort to determine the causes and consequences of legal scholars’ migration to foreign higher education institutions (hereafter, HEIs). Note that this text solely is focused on people who work and are dedicated to the academic legal research industry, excluding lawyers who migrated to engage in litigation or similar activities (although acknowledging it throughout the text). This article argues that the latter group has benefited from the goal to generate of high-level human capital, making them eligible to receive a National Council for Science and Technology (CONACyT) scholarship to study abroad, even without an academic profile.

Until the first quarter of 2020, CONACyT had 62 active scholarships for Mexican law graduate students (henceforth, MLGS) in foreign HEIs.4The term MLGS encompasses both LL.M. (Master of Laws) and doctoral students (Ph.D., S.J.D, and so forth) for the purposes of this text. Between 2012 and the first quarter of 2020, 632 MLGS have obtained CONACyT resources to study abroad.5

II. Who is a Legal Researcher?

For purposes of this study, a legal researcher is a person holding a position with assigned financial resources to conduct academic legal research. In Mexico, there are two main ways to receive payment for this purpose: through the National System of Researchers (SNI) and through bonuses awarded by the HEI employing them. As we will see below, legal research is not a common requirement for legal professors in the country.

Not all Mexican legal researchers are registered in the SNI. This limitation on including only SNI-registered legal researchers is made for methodological practicality since there is a registry of beneficiaries with data that assists to their quantification and identification of researchers, contrary to the case of unregistered researchers who work in other diverse areas, such as private companies. This aspect requires further research, but does not impact the intent of this article.

The purpose of the SNI is to promote and strengthen, by means of periodic evaluation, the quality of the scientific research produced in the country or by Mexican researchers living abroad.6 Anyone registered in the SNI receives economic stimuli according to their assigned level.7 To register, a researcher must meet the following requirements:

- Have a doctoral degree;

- Produce scientific and technological knowledge; and

- Participate as a member of the scientific community, for the three years prior to the date of the request.8

The committee assesses candidates under a specific criterion, which includes scholars’ leadership, participation in academic activities, human resources training, thesis direction, dissemination of knowledge, and teaching, among others.9

Despite the presence of the SNI and other financial stimuli programs to incentivize new generations of researchers (legal researchers in this case), the Mexican legal education system is not particularly keen to develop such professionals. Moreover, even if there are individuals who succeed at getting hired to do research, the system does not provide an appropriate environment for them to remain in this line of work. This context is the main reason the CONACyT financial stimuli (scholarships, SNI, etc.) fail to foster scientific research in law.

To prove this, let us make a succinct analysis of the Mexican legal education system:

III. The Mexican Legal Education System

Mexican legal education offers the following degrees: undergraduate, specialization, master’s degree, and doctoral degree.

1. Licenciatura en Derecho: Bachelor of Laws

In this section, the author will describe the undergraduate law degree in Mexico: the Licenciatura en Derecho (hereinafter, LED). According to Lopez Hurtado’s research, the most important characteristics of the principal program in this legal education system are:

1. [U]nlike in the U.S., [the LED is] an undergraduate degree earned after graduation from high school.

2. [Between 2006 and 2007] there were 930 institutions offering the legal bachelor’s … fewer than 20[%] of them were involved in research or other scholarly activities.

3. In most institutions, the curriculum is rigid.

4. More than 90[%] of the law professors combine teaching with professional practice; most law degree programs do not have full-time faculty.

5. The cost to open and run a law degree program is low. All that is required … is a few poorly paid lecturers, one classroom for each level of students, and a library with the books recommended for each course.10

Both public and private HEIs offer LED programs. However, the number of institutions varies tremendously from one sector to the other. In its 2019 Annual Report, the Center for the Study of Teaching and Learning Law (CEEAD) reported that 91% of Mexican law schools were private HEIs.11 However, these schools hold 33.24% of total national enrollment in undergraduate degrees, and 38.04% at the graduate level.12 This means that, although larger in numbers, private HEIs usually have fewer students. According to Perez Hurtado, for private law schools to obtain the certifications necessary to operate: “…[R]ecognition or incorporation can be granted by a) the federal government by presidential decree; b) the federal government through the Ministry of Education; and c) state governments through their respective ministries of education, but only for institutions and programs within that state”.13

Incorporation is granted by public HEIs, decentralized entities created by the federal government or by states (the latter admit private institutions and academic programs within that state).14

All institutions are free to set the content of their law program curriculum and what the student must do to obtain a license to practice, which is valid in all Mexican states, and not restricted to requirements set by a local bar association or the judicial branch of government as in the United States.15 Moreover, law schools are allowed to offer several “options for degree conferral”. A priori, thesis writing was the only way to obtain a law diploma. However, in recent years, the following alternatives have been added:

The “automatic degree conferral” or “option zero” includes the sole requirement that students must pass all courses and complete pro-bono work … [and] the standardized general exam to graduate … The third option for degree conferral is “professional experience”, which means the law graduate has worked at least five years in a law-related job.16

The thesis option has been quantitatively squashed. To give an example, of the 29,335 students who graduated in 2019 from all the fields of study offered at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), 76% (23,843) obtained their degree through options other than the traditional thesis or thesis and professional exam.17 According to the TESIUNAM platform, 369 theses registered at the School of Law between 2019 and 202018 No other law school in Mexico has this data available to the public.

Therefore, the LED program can be described as a massively extended cheap-to-install basic law degree with a tendency to create lawyers to meet the corporate need for a legal workforce, with a fixed curriculum, taught by part-time teachers, with little to no interest in producing research.

Until 2003, the Licenciatura en Derecho19was the higher education program with the highest enrollment in Mexico. Perez Hurtado points out that HEIs have rapidly increased their capacity to offer this degree. In the 1997-1998 school year, 364 schools offered a law program. By the 2006-2007 school year, that number grew to 930.20 Carbonell points out that out of 2,602 universities in Mexico,21 1,608 offers an LED, which means there is one law school per every 69,861 inhabitants.22 The most recent CEEAD report states that there are 2,332 law schools with authorized LEDs.23

This vast expansion resulted from the efforts to extend the availability of education in Mexico and, more specifically, the low cost involved in opening and operating a law program in the country, as Perez Hurtado explains.24

2. Graduate Level

Both Becerra Ramirez25 and Perez Hurtado26 maintain that there is a marked tendency for LED students to enroll in graduate programs immediately after obtaining an undergraduate law degree. Their main motives are further specialization, filling educational gaps in the LED, unemployment, curriculum building; and embarking on a career as a legal researcher.27

The Mexican Master’s degree has two lines: the professionalizing stream and research-intensive. Becerra Ramirez points out that the first one teaches students to find knowledge by themselves; rather than providing all of it through instruction, hence, preparing them for legal research (it is not, however, mandatory to generate new legal knowledge). This could lead them to find tools to go on to doctoral studies. In the second line, students must seek and create knowledge by themselves, which places them on the doctoral studies track. The author agrees with Becerra Ramirez’s assertion that the main issue surrounding master’s degree studies in Mexico is the structuralizing efforts done by HEIs.

The selection of students precludes the academic background of those who seek this degree which has students taking courses for approximately two years in a school setting without fostering researching efforts, but many curriculums for this degree seem like just a continuation of the LED studies.28

The highest degree conferred by Mexican Law schools is the Doctorado en Derecho (Doctor of Legal Science). Becerra Ramirez argues that the Mexican doctoral degree should be both research-intensive (as it is its nature) and specialized. He argues that this scenario is possible under the idea that specialization programs are used to disseminate and systematize existing knowledge, rather than formulate new ideas. However, he deems it important for universities to define the profiles of their programs.29

Becerra Ramirez mentions a “demographic surplus of doctors”, which takes from Marcos Kaplan’s “lumpenintelectual” concept.30 He argues that the idea (promoted by the government) of national development based on the existing number of doctorate graduates is a fallacy because of the lack of job opportunities for these graduates. On the contrary, that public policy produces a brain drain since doctoral students are compelled to emigrate abroad or stay in their hosting countries or perform other jobs.31

3. Part-time Programs

Another setting detrimental to Mexican legal graduate education is the part-time program. Mexican law graduate programs started in 1949 with the publication of the Statute of the Doctorate in Law at the UNAM.32 Throughout its history, the initiative lacked the financial and human capital to satisfy the program’s demand.33 As a result, UNAM chose to set up weekend graduate classes, considering the professional lives of its applicants while translating into strenuous workdays for teachers, anti-pedagogical classes, and students with limited time to study.

These types of programs do not have a specialized research focus which, along with the eagerness of law schools outside of Mexico City to imitate UNAM graduate programs,34 meant that subsequent attempts to set up graduate course platforms around Mexico were sterile in terms of legal research.

Nicholson and Trumbull presented data indicating that part-time evening schools faltered in terms of producing legal research. Trumbull’s experiment states that, particularly, students enrolled in these programs lack the time to conduct independent research,35 placing them in a disadvantage against their full-time counterparts.

The creation of full-time programs in the country would lead to more legal research, at least at the graduate level.

4. The PNPC and Legal Researchers per State/University

There is a policy to establish more full-time graduate programs. The mission of the National Quality Graduate Program (PNPC) is to promote continuous improvement, to ensure the quality of the national postgraduate degree, to increase the country’s scientific capacities, and to incorporate knowledge as a resource for Mexico’s development.36 Within PNPC’s categories, we find School Programs, subdivided into a) Research-Oriented Graduate Programs and b) Professional Graduate Programs.37

The PNCP assigns scholarships for full-time students taking academic programs registered within it.38 However, not many programs are registered in the PNPC. The first subcategory has 25 PNPC approved legal research programs in Mexico. As the focus of this article is on Mexican legal researchers, this subcategory draws the author’s full attention. The five states with the most programs are:

In total, there are 774 legal researchers registered in the SNI,40 distributed across the country as follows:

If we consider the history of the Mexican law graduate level, we can see that UNAM had the advantage of having an Institute for Legal Research (hereafter, IIJ-UNAM) since 1940, which allowed the institution to generate the scientific knowledge long before most universities in Latin America.42

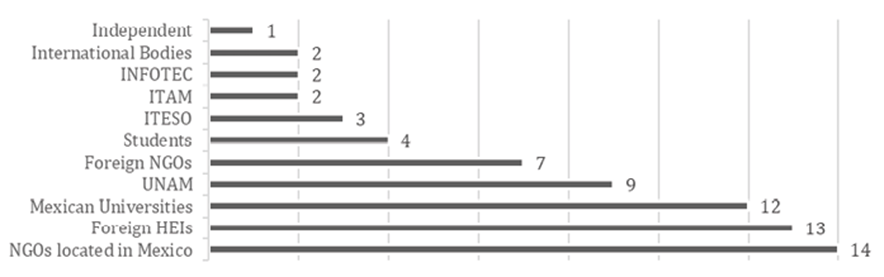

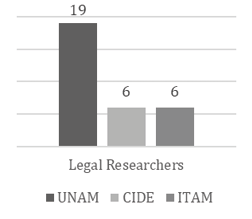

Only 25 of 1,528 postgraduate programs with PNPC accreditation are law programs.43 As Godinez Lopez points out, only 6.2% of the PNPC programs in Mexico belong to private HEIs.44 As we know, 1984 saw the creation of the SNI. According to the 1985 IIJ-UNAM activity report, the Institute had 47 legal researchers among its ranks, with 34 academic technicians.45 The graph 3 illustrates the distribution of the SNI by institutional affiliation.

UNAM has an advantage of 95 legal researchers registered in the SNI over its closest competitor (UANL). Through the data compiled in the graphs, legal researchers, according to the variables presented, are mainly centralized in one region and in one institution: The Mexico City Metropolitan Area and in UNAM.

Under the circumstances, legal research oriented graduate PNPC programs (albeit their names) have insignificant impact on the number of researchers. However, this seems not to be the case at UNAM. IIJ-UNAM is (practically) the sole source of legal information with its (up to 2020) 13 law journals, over 5,380 law books produced,47 13 law collections,48 and 39,060 law articles,49 among other non-written media. From the research conducted by the writer, there are no other legal research institutions that promote this type of legal content, regardless of the presence of law journals.

There is a lack of interest in heightening legal education in Mexican law schools, since success in the legal industry does not rely on the quality of the legal scholars’ work, but on their capacity to weave personal social networks that translate into favors and patronage. Becerra Ramirez points out that this situation holds a kinship with the Soviet Union’s concept of “zbiasi”, a system in which obtaining boons through legal and social channels was the rule.50 How does this impact Mexican legal research?

IV. Mexican Legal Research

According to Lopez Ayllon, Mexican legal research has not been able to provide legal solutions to the changes the country faces.51 Perez Cazares adds that Mexican legal researchers focus, primarily, on dogmatic and non-transcendent research, circumscribed only to commentary on law and doctrine.52 He attributes this shortcoming to mediocre legal pedagogy and the lack of professors with a background in legal research, an educational system designed to make obedient students, and the abuse of rote learning.53

Many authors have listed deficient teaching as the main problem surrounding legal research in Mexico. Sanchez Vazquez states that the current teaching method is magister dixit, a medieval method in which the only person with knowledge inside a classroom is the professor, while the students are passive recipients of said wisdom.54 Mexican legal education is “authoritarian, informative, monologue, immutable, passive, receptive, rote, descriptive, tame, and uncritical”.55 This restrictive doctrine does not encourage students to do research, nor does it require the professor to produce it. This puts Mexican legal education in a state of under-theorization.56

Various authors have blamed the magister dixit method for hindering the production of new legal researchers and for being an antiquated teaching method. Camilloni advocates for legal education that fosters students’ creativity by means of newly generated content added to objects of knowledge for classes, departments and research and teaching institutes.57 Moreover, as Elgueta and Palma point out, the magister dixit method has been scrutinized since the 1950s, with much criticism aimed at the passivity it imposes on law students.58 This teaching methodology is widely condemned, and it might have the greatest impact upon the production of original legal research.

1. Volume of Legal Research Produced in Mexico

According to SCImago, Mexico produced 117 law-related papers in 2018,59 representing 5.22% of the 2,238 social sciences articles published in the country that year.60 Scopus shows that production in 2015-2017 was 321 articles, published in five journals owned by one sole publisher: UNAM.61 Journal Citation Reports has only one Mexican law journal registered in its database62 as is the case in W&L’s index.63 Unsurprisingly, UNAM has both journals. In comparison, Canada (a country with only 21 law schools, meaning that there is a law school per 1,673,891 inhabitants)64 has 60 journals registered in the W&L’s index65 and, according to SCImago, produced 1,046 law papers in 2019.66

According to Sanchez Trujillo, there are around 2,000 law journals in Mexico.67 However, of the 216 scientific journals arbitrated by CONACyT, only nine are law journals.68 Sanchez Trujillo points out that the researchers interested in writing and peer-reviewing tasks are scarce,69 a situation that might be due to the type of legal education in Mexico, which does not produce researchers but legal technicians.

Overall, Mexico’s production of legal research reveals the poor quality and passive setting of its legal education system. Aside from UNAM and few other exceptions, practically all the other law schools are the passive recipients of the transmission of the knowledge produced by IIJ-UNAM.

V. Is Legal Research Remunerated in Mexico?

Another contributing factor for Mexican legal scholars to migrate abroad is how unlikely it is for them to attain a livable salary once inserted in the system. As stated previously, legal research can be paid in the form of wages and incentives awarded by HEIs (both public and private) and/or through resources awarded by the SNI. The first surpasses the second, as resources provided by HEIs are the main source of income paying for legal research in the country, especially since most professors employed by a given university are not members of the SNI. For example, in 2021, only 54 out of 1,388 professors employed by UNAM were SNI researchers.70 IIJ-UNAM’s personnel and Law School salaries71 greatly surpass SNI resources as the main funding source of legal research in the country.

Mexican public schools are usually ranked to receive research stimuli. Although the ranks are mostly similar throughout the country, they may vary from one institution to another. Here are the monthly salaries offered by five public HEIs to their highest-ranked professors:

The National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) has established that any person with a salary under $11,290.80 MXN77 per month is living below poverty level. None of the higher-ranked professors employed by the five chosen institutions belong to the poverty levels set by CONEVAL.

The reality is very different for the lower ranks, who must gamble with their economic security while hanging on in the lower ranks, which will, undoubtedly, require them to take on a second job. Last reliable data on salaries reported by professors on the private sector is dated from 2009, showing that the wages ranged between $13,325.00 MXN- $27,764.00 MXN, on average.78

Not all the law school professors receive the salaries detailed in the table above. Most of the professors working in private HEIs receive an hourly wage.79 Although the information on wages of private universities’ professors is unavailable, in the case of public universities, that information is public. These are the salaries of professors hired under this type of contract:

This is a peek at what being a part-time professor in Mexico is like. However, this researcher found that 86.7% of the academics working at those institutions were doing so under hourly wages. The panorama is not much better in public HEIs since 60.24% of the professors were employed under the same circumstances.85

The differences between the wages offered by private and public HEIs do not vary much, although the labour conditions of private law schools are worse than public ones. In private schools, most law professors receive their wages under a concept known as “honorarios”, which is the remuneration received by a professional who practices their profession independently, with no labour relationship and as a service provider.86 Under this labor scheme, law professors in private HEIs do not get social security or other employment benefits. Meanwhile, most teachers at public universities receive all the social security benefits established by Mexican labour law.87

91% of law schools in Mexico are private and cater to all types of budgets (elite, middle class, and working-class sectors).88 Acosta Silva argues that the sector constantly produces newer but unprepared private HEIs that imitate large elite private universities.89 These institutions prioritize labour market insertion; research also seems to be oriented towards that goal.90 Herrera Guzman points out that research is not a priority for recently created private HEIs due to the lack of resources, which are mostly directed at covering wages and current expenditures.91

2. Tuition Fees: Their Importance for Salaries

Raising tuition fees is a common proposal to alleviate financial problems in public HEIs. However, this might not be a possibility due to the economic reality of many Mexican citizens.

Tamanaha argues that US law teachers are among the best paid around the world. Between 1998 and 2009, they have seen their wages increase by 45%, with senior professors at top schools receiving better salaries than federal district judges. According to Society of American Law Teachers data, the average median salary of a full-time professor in 2008-9 was $147,000 USD a year. These sums are primarily attained through hefty tuition fees, leading to debts that students will never repay without an average salary of $85,000 USD.92

The Mexican government largely subsidizes tuition fees, a policy that has helped Mexican college students repay their debt in under six years.93 As we can see in the UNAM’s 2019-20 budget, the Mexican government provided a subsidy covering 88.61% of the budget, whereas tuition represents a mere 0.07%.94 The system has its shortcomings, but it has undoubtedly increased the expansion of public education throughout Mexican territory. However, it does affect professors’ wages.

Whereas US law schools try to offer the best salaries to their teaching staff to keep the best roster possible away from competing law faculties and firms,95 Mexican law schools have cut this competition by setting up an internal labour market, ruled by the present academic body and their labour unions. This means that Mexican law professors are in a conundrum in terms of obtaining better salaries. On one hand, law schools are blocked from increasing their tuition fees because it would directly affect expanding higher education in the country, thus limiting access to law schools to impoverished sectors of the population. The shape of the internal labour market in the Mexican academic industry represents an obstacle for lower ranked educators to climb to higher levels, as they would be even more hindered by the usual corruption in evaluations and the politicization of the committees in charge.96 New recruits would face meager wages for most of their academic careers, without access to financial mobility due to the monopolization of higher ranks.97

3. Which Setting Offers the Best Platform for Legal Research?

Public universities employ the most SNI researchers, reaffirming that private universities do not focus on producing scientific research. 477 of the 774 SNI-registered law researchers are currently working in a public HEI, whereas 134 of them belong to the private sector.98 Due to their private nature, it is hard to distinguish how these institutions conduct and finance scientific studies.

Private HEIs do not have legal or public policy constraints preventing them from raising their tuition fees, which might explain why Maldonado-Maldonado arrives at the conclusion that these HEIs paid more on average.99 But, as seen, 86.7% of the academics working in private HEIs were employed by hour whereas 60.24% were under the same setting in public HEIs.100

Therefore, we have that, although both scenarios are grim, public HEIs do present a more financially stable platform for legal research due to the existence of government subsidies for academic staff carrying out scientific research, albeit the processing and the amount of said resources are not the most advantageous.101

VI. SNI

Legal academics can apply for registration in the SNI program that gives financial resources to scholars producing research. However, only 774 legal researchers in the country receive said stimulus. There are four SNI levels, each of which is assigned a specific amount. The financial stipends are shown in Units of Measurement and Update (UMAs) as follows:

- Candidate: Three times the monthly UMA value102 ($2,925.09*3 = $8,775.27 MXN).

- Level I: Six times the monthly UMA value ($17,550.54 MXN).

- Level II: Eight times the monthly UMA value ($23,400.72 MXN).

- Level III and Emeritus: Fourteen times the monthly UMA value ($40,951.26 MXN).

- One-third of the stimulus for candidate level is assigned to researchers outside Mexico City ($2,925.09 MXN).103

As per the last SNI report, there were 227 legal researchers at candidate level, 399 at Level 1, 88 at Level 2, and 60 at Level 3.104 These amounts are not part of the wages or salaries these researchers perceive at their educational institutions.

Are these stipends enough for a legal researcher in Mexico? It would depend on the researcher’s main salary. Salaries vary according to the nature of the HEI (whether private or public) and the location of the law school.

1. The SNI and Wage De-Homologation

Although wage de-homologation has worked in terms of strengthening academic bodies in public HEIs and linked participants to other research platforms like the SNI,105 its goal is not to provide researchers with decent wages or to increase the number of institutions where they might work. In 2011, the Comprehensive Institutional Strengthening Program (PIFI) was born with the objective to improve and strengthen the quality of educational programs.106 Resources are awarded through a competitive process, with academic bodies (or individuals) delivering academic products (not always related to research) in hopes of securing funding. In essence, the PIFI intended to de-homologate wages with, alas, the same effects. The fact is that this policy has resulted in a myriad of complaints from the scientific sector: clientelism,107 lack of professionalization,108 insolvency and bureaucratic protectionism (which puts students and researchers at the bottom of CONACyT budgetary priorities),109 among others.

There are voices asking for the elimination of the SNI, making its resources available through a full salary.110 Granados argues that the SNI is nothing more than a productivity stratagem that prevents researchers from attaining decent salaries.111

If legal research continues to be perceived as an extra feature of Mexican legal education financially rewarded through highly productivity but insufficient stimuli, Mexican law professors will not feel compelled to generate original research. The author of this piece subscribes to Vera’s opinion: “Every teacher (including subject teachers) should receive a salary that adequately covers their needs, and that does not happen today. None should have their income conditional on evaluations”.112

Moreover, law professor candidate research portfolios should be a standard hiring requirement/consideration in all processes; excluding, of course, practicum teachers, as their profiles are not predominantly centered on research. If it were so, there would be no need for a SNI since legal research would be an integral part of the profession. Therefore, salaries should be increased to reflect the hypothetical disappearance of the SNI. However, as Vera himself admits, the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit would not allow it.113 Advocacy and the formation of organic academic and research faculty is needed, but the magister dixit methodology makes it improbable that the number of research-interested law professionals will increase to a volume large enough to make this a reality.

VII. Centralization

UNAM is the preferred university for students interested in conducting scientific research.114 As seen in SNI numbers, public financed legal research is (practically) centralized in IIJ-UNAM. The overwhelming number of SNI researchers at IIJ-UNAM is explained because it is a research body solely dedicated to producing original legal research. Moreover, the UNAM School of Law has started the Project to Promote the Entry of more academics into the National System of Researchers (SNI), to raise its quality of education.115 This situation only exists in UNAM and a handful of other institutions (i.e., CIDE, UANL).

Despite the poor wages offered in the country, legal researchers see IIJ-UNAM as one of the few possible employers in Mexico to conduct academic legal research. This institution has 1,388 law professors116 (134 in the SNI) supported by 544 support staff members facilitating the creation of academic clusters, research groups, law journals, etc.117 These crucial factors are what foster the “monopoly” of legal research within IIJ-UNAM halls.

Sanchez Trujillo purports the idea that there are around 2,000 law journals in Mexico.118 However, the absence of peer-reviewers and writers reported by Sanchez Trujillo makes it clear that Mexican legal research is but a shell without substance in most institutions. This is one of the negative consequences of the rigid curriculum of most LEDs in the country. Students are taught with outdated methods and theories, nor do they question the information provided by their instructors, which provides the latter with no incentive to update their materials. The lack of demand for new knowledge makes legal research an extra feature of legal education rather than its catalyst. To change this situation, the law curriculum should be revisited and discussed among law professors nationwide.

UNAM itself recognized this situation back in 1983, in one of their Annual Evaluations of the Work at IIJ-UNAM, reporting that the work they did at provincial universities only consisted of teaching since “they do not have, except one, an institute, division or department of legal research”.119 In 2002, Sanchez Vazquez complained that the situation for law schools outside Mexico City are very different from that of UNAM:

[There is a] lack of documentary and human infrastructure. In other words, it has been very difficult for postgraduate courses in the [states] to have worthwhile libraries and newspaper archives … in virtue of this, if we compare these collections with those of the Institute of Legal Research library at the UNAM, they do not exceed 8%.120

Universities outside Mexico City have no interest in having their academic staff become doctoral scholars. The “research professor” concept is recent in Mexico, and time and resources are needed to put together and support a research body to conduct research.121

Establishing research institutes is costly. The IIJ-UNAM total budget for 2019-2020 was $306,082,256.00 MXN, with 72% of these resources allocated to salaries, benefits, and incentives.122 In comparison, the UADY’s School of Law had a total budget of $37,854,000.00 MXN.123 Financially, law schools, aside from UNAM’s, would view the creation of a legal research institute as a luxury.

1. CONACyT Policies

Centralization is not unbeknownst to the Mexican government, as it has previously tried to foster the reintegration of graduate students with degrees from foreign institutions by offering scholarships or cancelling student debt if they migrated to other cities in the country. The idea was to distribute resources in a way that would promote equity and decentralization by means of the compensatory allocation of available resources to regions outside Mexico City.124 However, there are no records on the efficiency of this policy.125 Alongside the decentralization policy, CONACyT has a repatriation policy and a professorship program.

The repatriation policy aims at incorporating researchers with research experience both abroad and within the country.126 CONACyT will provide the beneficiary with a monthly stipend of $30,000 MXN for the next 12 months and a one-time payment of $36,000 MXN for relocation. Researchers who are heads of households will receive an additional monthly bonus of $3,000 MXN for 12 consecutive months.127 Since its creation in 1991 and until 2015, the repatriation policy has brought back 3,062 researchers.128

In the 2000s, public investment in the program dropped due to a lack of interest in repatriating Mexicans who studied and were working abroad, which led to a steady decrease in repatriations. Izquierdo argues that one of the main issues raised about this policy at the time was the lack of full-time jobs for the repatriated people.129 In general, the rate in the 1990s was about 40 returnees for every 100 doctoral students studying abroad with CONACYT scholarships, but by 2016 the rate had decreased to only 1 returnee per 100 PhD students abroad.130

Moreover, as García Pascacio, et al. pointed out, the lack of research groups prevents proper repatriations.131 The presence of the magister dixit method and the lack of the legal research centers circumscribe successful repatriations to a handful of institutions (namely, the IIJ-UNAM and the UANL legal research center). Therefore, and due to the inability (nay, disinterest) of the private HEIs, which have the most law schools registered in Mexico, the possibilities of attaining a job as a legal scholar in Mexico are very reduced.

The CONACyT professorships program originated with the 2013-2018 National Development Plan, as part of the national “Mexico with Quality Education” goal. It aims at making scientific, technological and innovation development the pillars for economic progress and social sustainability in the country and generating an important number of highly qualified human capital by incorporating researchers into the knowledge market and thus reaching levels of global competitiveness and productivity. Currently, 1,076 researchers carry out 664 research, innovation, and technological development projects in 132 institutions in all the states in the country. In 2014, CONACyT awarded a monthly wage of $30,676.05 MXN to those benefitting from this program.132

Neither the repatriations133 nor the professorships programs134 have registered legal scholars or projects. The decentralization of legal research will take more than just resources to become a reality.

VIII. Are Mexican Legal Scholars Migrating?

Who falls under the category of migrant legal scholar? Anzures Escandon uses the term “brain” to refer “to those individuals who hold at least a BSc degree obtained in Mexico”.135 I will use the same definition, but changing the BSc degree for the “Bachelor of Laws” degree.

One of the most common ways MLGS study abroad is through scholarships offered by CONACyT. Anzures Escandon argues that the scholarships foster “a model of mobility biased to the U.S., in view of the lack of job opportunities or the low wages offered to graduates”.136 Garcia Pascacio argues that these scholarships are “an invitation to migrate”.137

No research has been done on how many law students have left Mexico to pursue postgraduate studies in law at foreign universities. The author decided to use the CONACyT Registry of Scholarship Recipients (RSR), a registry with the names, destinations, and scholarships granted to Mexican students pursuing graduate studies, in order to obtain the corresponding figures.138

1. CONACyT Scholarships to Study Abroad

Anzures Escandon argues:

The [CONACyT] scholarship programme is the most important asset for talent formation/forming/developing talent in Mexico. [Its] priority was to increase the number of teachers and researchers in Mexican higher education institutions, as well as to support the creation of research centers across the country.139

After consulting RSR data on scholarships awarded between 2012 and the first quarter of 2020 and filtering out other fields of knowledge, 632 law students received CONACyT resources to study abroad. The RST includes information on students’ names, duration of the scholarship, levels of studies, hosting institutions, hosting countries, programs, areas of knowledge, and amounts paid to the institutions.

Aside from CONACyT scholarships, MGLS can receive other scholarships like the Chevening while others even resort to bank loans to finance their studies. However, since banks are private companies, data on specific MGLS who applied for loans were unavailable for this research.

2. Survey: Using the RSR and Contacting Students

MLGS were located through LinkedIn, along with information on which university they obtained their bachelors’ degrees and their current jobs. Those who responded were asked the following questions:

- Question 1: Could you describe your experience as a law student in Mexico, and the differences you find between the foreign graduate program you took and the LED?

- Question 2: Do you aspire (or did you aspire) to stay in the country where you are pursuing (or pursued) studies to obtain a job as a legal researcher (whether for a university, NGO, government, etc.)?

- Question 3: If so, did you encounter any kind of obstacle when making the same attempt to find a job in Mexico?

From the original 632 student sample, 106 could not be contacted by any means possible. Moreover, there was no reliable information in terms of employment or alma maters. Therefore, the sample was reduced to 526 as per the criteria described in this paragraph. They were contacted via LinkedIn or email, with 54 people responding to the survey questions.

3. Demographics

A. Gender and Alma Mater

In terms of gender, the MLGS sample consisted of 327 males and 307 females. Among those who were legal researchers, 43 were women and 28 were men. As we will see later, researchers (regardless of gender) are a very small minority. Which Mexican HEI sends the most MLGS to foreign HEIs?

Of the 10 universities mentioned in the graph, seven are private HEIs. Five of these institutions (Ibero, ITAM, ITESM,140 ELD, Panamericana)141 are regarded the most exclusive institutions in the entire country. The numbers shown on Graph 4 are comparable to the ones purported by Arceo Gomez et al.142

The students enrolled in these HEIs generally come from wealthy backgrounds, meaning that those resources are often awarded to people who might not need them in the first place. It is impossible to assess the socioeconomic background of MLGS in the sample, but we can infer that the prevalence of private HEIs in the number of MLGS in the sample is due to the credit-like nature of CONACyT scholarships for studying abroad, which means that students must repay the amount.144

Class privilege145 might play an interesting role in the awarding of CONACyT scholarships, which contradicts several CONACyT announcements requiring the validation of applicants’ socioeconomic situation condition when reviewing eligibility for financing.146 This context is important since, as Anzures Escandon points out: “Privileged immigrants (skilled individuals among them) are more likely to enjoy the benefits of these contemporary migration dynamics than their unskilled, generally poorer counterparts”.147

In most scholarships announced for 2020, CONACyT excluded legal studies from its priority areas148 established by CONACyT and a secondary sponsor. This is one of the main reasons why MLGS with active CONACyT scholarships in 2019 were outnumbered by other disciplines that CONACyT did consider a priority.149 Granting scholarships to students from privileged socioeconomic backgrounds is not inappropriate, but attention should be brought to the fact that most of the limited opportunities to study law abroad are given to these students.

B. Cities

“Patterns of migration are usually interregional, intra-state or rural-urban before they become international”.150 This is known as “internal brain drain”.

From the cases we reached out to, 368 MLGS obtained their undergraduate law degree from a university in Mexico City, revealing the very remote possibility for students from HEIs outside Mexico City, Monterrey, Puebla, and Guadalajara151 to obtain a CONACyT scholarship to study abroad, with only 64 cases seen in this graph.

The above cited Arceo Gomez et al. states that:

Our analysis shows high degrees of concentration in the distribution of educational quality at the highest level in the country, both geographically and institutionally. Mexico City and the northeast of the country represent 60% of the total applications in 2013-2016 … As for the [South], only 144 of the 2,507 higher education institutions registered with the ANUIES sent at least one scholarship application to [CONACyT] during the period in question.152

C. Scholarships Used

As the information on the scholarships granted between 2013 and 2018 is incomplete, this MLGS sample consists of the 482 were registered on the CONACyT webpage. The following graph shows the scholarships used by MLGS:

As seen, FUNED (a non-governmental organization) represents almost half (236 of the available 482) of the scholarships sample. This financial support consists of monthly financial support for paying tuition up to an annual amount of $76,800.00 MXN. FUNED assists students with a $15,000.00 USD loan.153

This scholarship establishes several selection criteria. The one that most stands out is an assessment of the applicants’ socio-economic situation.154 The graph of the alma maters of MLGS revealed that most of them obtained an undergraduate degree from exclusive private schools. A desired socio-economic background for applicants is not established in the rules or in calls, making this requirement inconsequential. Its purpose might be attributed to the fact that the support is basically a loan, which would explain why students with greater purchasing power have greater access to aid.

Consequently, 160 of FUNED recipients come from private HEIs (120 from Mexico City). FUNED itself stated that private HEI recipients (from all fields) represented 80% of the cases in its 2019 report.155 Moreover, there are four dominant institutions: Ibero (36), Panamericana (32), ITAM (30), and ELD (13). From public HEIs (46), we have that UNAM (21) and CIDE (11) have 69.56% of the beneficiaries. 30 awardees did not have information regarding their alma mater.

In second place, we have the “Becas al Extranjero” scholarship. The call for this scholarship states that “priority shall be given to doctoral studies and programs related to the areas established by the Special Program for Science, Technology, and Innovation (PECITI)”.156 Legal studies are not included. However, “applicants whose study program is not contemplated in [these] areas may apply”.157 This clause has an actual impact on the type of applicants pursuing this financial ais since 73 of the 137 recipients were doctoral students. In terms of geographical distribution, “Becas al Extranjero” scholarship recipients are well-spread across the country. In our sample, 10 states were present: Mexico City (20), Nuevo Leon (3), Jalisco (3), Sonora (2), Puebla, Michoacan, Guanajuato, Tamaulipas, Baja California, and the State of Mexico. UNAM had 10 beneficiaries of this scholarship.

Overall, scholarships are as centralized as the production and legal research platforms. Arceo Gomez et al., believe the main reason for this situation is because scholarships are mostly promoted in a handful of universities, founding that 10 private HEIs have higher “application per student” rates than those in the rest of the country. Moreover, as these researchers state, the patterns of segregating universities in the applications will not change if the quality of basic and upper secondary education is not improved. Even then, these inequalities should not be exacerbated in access to scholarships to study abroad.158

D. Doctoral Students

The “Becas al Extranjero” gives preference to doctoral students. Since these programs are, by nature, research-oriented, they are the perfect way to identify potential legal researchers. Out of 570 MLGS CONACyT scholarship recipients, 104 were doctoral students. To prove that these students are likelier to obtain legal research positions, it is necessary to look into MLGS’ current occupations.

E. Employment

In this section, we list MLGS’ current occupations. However, 119 of them did not have any work-related information on their LinkedIn profiles or any public information on that point.

This graph shows that between 2012 and 2020 CONACyT scholarships helped produce 69 legal researchers. Although (both national and international) academia employs most of them, non-governmental organizations have played a key role in providing 21 jobs for such professionals. Four cases of people who are currently studying abroad but answered that talks were already underway to fill the ranks of a Mexican university as a legal researcher were included in this tally. Doctoral students were keener to get legal research positions than were other students. From the sample, 42 doctoral students are now currently employed as legal researchers, compared to 27 masters’ degree students. If we classify MLGS by their degrees, 40% of the doctoral students landed a legal research job, while only 5.80% of master’s students did. The following graph shows places employing legal researchers:

From the data we can see that 47 individuals are working in Mexico as legal researchers, only 8.93% of all MLGS who received a CONACyT scholarship to study abroad. The remaining 22 are part of the “brain drain”.

As for undergraduate degrees, the Mexican universities that have produced the most legal researchers between 2012-2020 and a comparison between universities with lawyers working in other sectors are shown in the following graphs:

With these graphs, we can see which universities are more likely to send MLGS for private-professional reasons or for academic purposes.

Question 1:

This is Minera’s answer to Question 1:

In academic terms, when I started my activities at the University of Alicante, I honestly realized that I was at a real disadvantage… there were great differences between my academic skills and those of other students… Furthermore, I was very used to a teaching/learning process where the student has little autonomy; that is, the professor tells you what to do. Meanwhile, the program I was taking gave me little along those line since student[s] were the ones who had to organize [their] time, look for [their] material, flesh out a project and deliver substantial progress.

As we can see, the magister dixit method had a negative impact on Minera’s academic development. She was a doctoral student who, as she points out, did not have coursework as part of the program.

Capirotada faced a similar situation while studying at McGill University:

…It was difficult since my education in law in Mexico [in the 1990s] was through the transmission teaching-learning process. In other words, professors only transmitted their knowledge and mainly evaluated by means of exams. However, the McGill University system was one of problematization, and therefore I had days to acquire the skills I had not acquired in years in the [LED].

Which are these differences? MLGS point out that the programs they attended focussed on legal theory side, instead of solely focusing on the practice. In Cuachala’s experience:

My graduate degree was in legal theory. So, comparing it to a bachelor’s degree is a bit difficult. It centered on Anglo-Saxon legal theories (Dworkin, Shapiro, etc.) and some continental European ones (Luhmann). In general, its approach was more discussion and case resolution, although perhaps the comparison between a national degree and a postgraduate degree abroad is not the same.

Graduate law programs in Mexico do follow a magister dixit setting like the one in the LED.159 On the other hand, foreign law graduate programs display flexibility in terms of how students gain and produce knowledge. Students are generally proactive, or at least programs do not see passivity as something desirable, unlike Mexican ones.160

One exceptional case was reported by some CIDE students. Huarache tells us her story while studying there:

At CIDE, I had courses that are quite scarce in other law schools: Introduction to economics, political science, legal analysis, legislative drafting. Most of these courses were part of the common core. In other words, I studied with guys from the Bachelor of Economics, Political Science, etc. The Legal Methodology course was our ‘filter’ since the CIDE aims at preparing researchers.

Moreover, Huarache had the opportunity to work as a Research Assistant, a rare figure in the Mexican legal education system. Another aspect we can extract from this testimony is CIDE’s multidisciplinary coursework.

Another interesting aspect shared by some MLGS is the desire to acquire knowledge on certain topics that are not available in Mexico. Camote’s experience shows that:

To give some background, I studied a master’s in International Tax Law [adv. Program] at the International Tax Center of the University of Leiden, in the Netherlands… [T]he teaching resources at the University of Leiden are superior to those in Mexican universities. The scope and level of my master’s degree are not available in any educational institution in Mexico.

Camote is a tax lawyer, with 19 peers among MLGS registered in the RSR. None of these 20 MLGS were working in academia.

Another aspect pointed out by interviewees was the language barrier. In the traditional format, the language barrier might be an obstacle to conduct research. Cabrito tell his experience: “As for the writing style, I am sure you understand me. In the anglophone world, you have to get to the point at the beginning of the article instead of giving too much context before coming to the results”.

English was the dominant language of MLGS’ studies. Studying law abroad is a matter of class privilege in many cases, exacerbated by the prevalence of English language classes in private education (a feature that was, until recently, almost exclusive to these institutions).161 Moreover, CONACyT only has scholarship agreements with universities in two Spanish-speaking countries (Spain and Costa Rica).162 Tejate has an interesting anecdote to this regard:

My scholarship application process was long and winding. I decided to study at [postgraduate institution] since it has interesting and fitting coursework form my research on Indigenous rights. However, when I started my paperwork to obtain funding, certain people from [public research institution] approached me and insisted that I study in Costa Rica, since the [postgraduate institution] did not have a scholarship agreement with CONACyT. After months of insisting and after paying tuition fees for the first year of my program, they granted me the scholarship. The institution reimbursed me for the money I had paid. However, I do not think this is proper by any means. I have talked with several other [MLGS] here in Spain, and none of them have mentioned a situation like mine. Moreover, to make matters even worse, they were not asked to comply with certain requirements made by [research public institution].

None of the other MLGS interviewed had a story like Tejate’s.

In sum, MLGS seemed to agree that their graduate programs were far superior to their LEDs. The magister dixit setting prevented them to be prepared for a maieutic structure. To take the classes properly, MLGS must study and read in advance. To do so, the professor must have a syllabus to guide students and establish the basic requirements to pass the course. However, this tool is quite rare in LEDs in Mexico and demands further research.

Question 2:

30 of MLGS (the majority) in the sample said that they were not aiming (or aimed) at staying in the host countries. The remaining 24 did indicate a desire to remain in their host countries or were already settled there. However, their reasons were varied. Starting with those who aspired to remain abroad, Calavera, a student who managed to obtain a job as a legal researcher during her doctoral studies, told us her story:

An important point I think should be mentioned is that the money I received to study abroad with a family (husband and son) was very limited. That forced me to look for a job to survive and finish my studies. As a result, by having to work I had to reduce the time dedicated to studying, which lengthened the duration of the studies themselves. For many people I know, this increases the risk of dropping out. I was fortunate to have my family’s support, both financially and emotionally … I believe that a more realistic financial aid and one more in tune with the real conditions and needs of students during their studies would help the completion rates of programs initiated and would facilitate their return to Mexico after completing these programs.

However, not all MLGS might have Calavera’s same luck. Among those who expressed their intention to stay, the main reason for returning home was the financial burden of remaining in their host country.

Certain MLGS who gave a negative response to the second question acknowledge that they were dumbfounded by the competition in their host countries. Discada tells us about her experience in Washington, D. C.:

After finishing my studies at American University, I was contemplating several possibilities to remain in Washington. However, my Fulbright Scholarship agreement (one of my three scholarships) had a clause that ordered me to go back to Mexico and stay there for at least 24 months. I talked to the Fulbright team and they told me that there were ways for me to stay in the US. However, they did warn me that it would entail a great sacrifice and, moreover, the type of temporary jobs available to me at the time would not allow me to have a credit history, among other basic concepts in American life. Furthermore, while I was there, my professors at the American University suggested that my area of knowledge (Environmental Law) was not in high demand. These, among other situations, convinced me to go back to Mexico, against my initial desires.

Only 4 MLGS currently studying aid to be in talks with Mexican institutions to join their ranks as soon as they finish their studies abroad. Mole Poblano had his alma mater offer him a contract to teach there even before he had gone:

When I got the news that I had been accepted into the University of Edinburgh, I called my university to tell them. I was already teaching there when this happened. Surprisingly, they assured me that I would have a job on my return to Puebla. My supervisor at the University of Edinburgh did offer me to stay there and do a post-doc, but I was under contract with UDLAP and I wanted to retribute the confidence they had in me.

Some interviewees could have stayed at their host institutions. Pambazo is considering staying as a clinical law professor. However, his true desire is to return to Mexico and teach law there. In a phone call, he shared that: “For personal reasons, my wife and I would like to go back to Mexico once we finish our studies here at Cornell. I was considering to seek employment outside Mexico City since [the Bank of Mexico] would cancel my loans if I do so”.

Pambazo showed concern regarding law professors’ wages, which shows that waiving MLGS’ loans is not attractive enough.

However, not all MLGS had Mole Poblano’s luck. Esquite did her doctoral studies in Australia. She was on a university’s payroll for 18 years, but quit after the institution denied her an academic position:

At first, I had no incentive to stay as I had a permanent position at [institution], but by the end of my studies, I was warned that there would be no growth in [institution]. So, I tried to look for a job as a full-time professor or tutor since I had already given some classes and tutorials. However, I was not successful. The subjects that could be taught at the time were generally given by nationals since the legal system is completely different. Upon returning, the [institution] itself denied me academic spaces, so two years after returning to the country, I submitted my resignation after working for them for 18 years.

Practically all the interviewees showed concern about the low wages offered by law schools in Mexico. MLGS currently studying did acknowledge that situation as the main issue that would persuade them to try to stay in their host country. Calavera was the only person among the 54 MLGS participating in this survey who mentioned “safety” as a reason to remain in the host country.

Question 3:

MLGS with more “traditional” careers in the legal industry (i.e., attorneys, corporate lawyers) had a higher rate of success than those who actively sought opportunities in the academic field. 27 out of the 50 MLGS in the sample were doing activities unrelated to academia. Most mentioned that their degree helped obtain a job. Sopa de Lima tells us that:

I tried to stay in England or in Europe, specifically in a UN agency. I also went to a job fair at my university and, talking to some legal firms, they told me that I had to start from scratch as an intern or trainee and that the subject of the work visa could be a deal-breaker. Most recommended that I register with their subsidiaries in Mexico or Latin America. In Mexico, it was easier. I arrived and with my credentials, I was offered a position as an advisor in a government agency, as well as in a law firm.

There were a couple of cases in which studying abroad helped MLGS interested in academia get a job. Guacamaya has something to share in that regard:

In my case, my desire to return to Mexico upon completing my studies and joining an educational institution was always clear. Although I really enjoyed my stay in [host country], I needed to give back a little of what had been given to me. Fortunately, my studies opened many doors and when I returned to Mexico, I had already won a competition for a position at a university.

Minera did not have the same luck:

Coming back to Mexico, it was extremely difficult to find a position as a researcher (it was even more difficult to find a position as a practicing lawyer). In some job interviews I felt that studying abroad was more an obstacle than an advantage because you do not generally even get an interview if you do not know someone who knows someone who can convince the decision-makers to give you a chance …I first tried to get hired with the CONACyT repatriation program, but none of the universities I visited was willing to commit with this program. UNAM was not an exception as they were not interested in the CONACyT repatriation program. They found the topic I suggested interesting and told me they thought my CV was extraordinarily strong, but they asked me to go through a postdoc application process.

Her testimony reminds us of the “zbiasi” setting described by Becerra Ramirez: the larger the network, the bigger the net worth. Moreover, we can see again that the CONACyT public policy is flawed when dealing with MLGS trying to return to the country. As seen in discussing this policy, there were no law projects or academics registered in either CONACyT repatriations or professorships.163

In most CONACyT scholarship calls, we read that the funds are directed not only to researchers, but also to “high-level human resources”. Neither Science and Technology Law nor the Regulations for the Promotion, Training and Consolidation of High-Level Human Capital Program Scholarships define what this concept means, so it is open to interpretation. 27 interviewed MLGS found employment in jobs unrelated to academia, so it is accurate to say that they are what CONACyT calls “high-level human resources”. Camote pointed out that the knowledge that he acquired was not available in any Mexican Law school, which led him to study abroad. Therefore, the author asks why the government (through CONACyT and other academic instances) does not foster Mexican law schools (and universities in general) to start producing their own knowledge instead of paying millions of pesos in tuition to educate its citizens in foreign HEIs. Given the risks of the current policy (such as brain drain), this stance unsustainable and unproductive as regards the country’s goals in science.

As the reader might recall, Esquite quit her academic job due to its lack of academic opportunities and platforms. The environment she describes does not seem ideal and would probably scare other MLGS from seeking employment there. However, other law schools might not offer the platform needed to conduct legal research among other shortcomings (i.e., very low wages). This situation is a conundrum rising from a lack, again, of legal research institutes like IIJ-UNAM. Is staying in a foreign law school the answer? Pozole’s experience might tell us otherwise:

It was not clear to me if I wanted to stay or not. But what I did want was to research Mexican and Latin American law, making it more logical to return to Mexico. Having an [LED] and not a [JD] or an [LL.B.] was an obstacle to teaching basic classes like Case Law in Sydney. The New South Wales State Bar asked for students with a barrister’s profile. So, the obstacle was rather the opposite and I wanted to go back.

Working in a different jurisdiction will always be the greatest disadvantage MLGS face while competing in a foreign legal academic setting.

In sum, MLGS seemed to have different experiences depending on their goals. Private sector and government lawyers benefited from attaining a postgraduate degree. However, those in pursuit of academic jobs have had several obstacles in their way.

Therefore, we can see that the Mexican legal education system is not designed to produce legal researchers, which is unacceptable for a country with problems of corruption,164 the Rule of Law,165 and a judicial system in dire need of reform.166 Despite this, the numerous means of financial support available/granted by CONACyT to Area V (Social Sciences) represents the biggest pool of SNI recipients in the system (774 out of 5,973).167

As the survey suggests, most recipients of these scholarships have ended up joining the ranks of the private sector. The relevance of using CONACyT scholarships to study abroad to train high-quality human resources goes beyond the intention of these lines and should be reserved for later studies. Nonetheless, the results of this survey are no more than an indication that scholarships (at least in legal sciences and law) do not end up in the hands of those who aspire to do legal research of any kind.

IX. Mexico City or Bust: Conclusions

Studying abroad is a privilege. This pattern is present in the MLGS sample shown herein. Following Aupetit’s arguments, we can affirm that the types of migration occurring among MLGS are for personal reasons and short-term stays. Only one person stressed “safety” concerns.168 In this sense, the answer to the question “is there migration of Mexican legal scholars?” is yes, but they are not the only ones.

As Anzures points out, the brain drain in Mexico refers, in most cases, to the professional elites of the middle classes.169 Moreover, students from only four cities (dominated by Mexico City) are those with a chance of studying in foreign HEIs. Additionally, the greatest advantage that Mexico City has in terms of researchers registered in the SNI (mostly arising from the presence of IIJ-UNAM) underscores the idea that it is the only place where legal scholars can get a job. The multidisciplinary setting of CIDE coursework (as mentioned by Huarache) may be encouraging, but it is not a deciding factor to produce more legal researchers. However, with CIDE in Mexico City, we could say that law students there have a socio-spatial privilege (a concept used in ableism studies),170 expressed in their evident greater access to financial resources to support their studies abroad (regarding CONACyT scholarships) and, above all, a variety of education systems other than the magister dixit method, thus effectively centralizing legal research in Mexico City, as well as the opportunity to study abroad. Class privilege comes into play while assigning the symbolic amount of CONACyT scholarships granted to other cities.

There is no demand for legal researchers due to teaching settings adopted in most Mexican Law faculties: the magister dixit method. In this situation, the production of new legal knowledge is considered an extra, and not the main catalyzer of the country’s law schools. Therefore, there is no need for legal research institutes, and hence, legal researchers.

The survey showed that MLGS in the sample were predominantly private-sector lawyers, working as litigants or corporate advisors. Considering Sanchez Vazquez’s assertion, the low volume of legal researchers is caused by a disinterest in legal research more than the centralization of legal knowledge, per se. Moreover, individuals who finance their studies with loan-type scholarships (like FUNED) might expose themselves to poorly paid jobs in academia during the early stages of their careers. Eventually, these scholars might have to turn to the private sector to do activities unrelated to research in order to repay their debts. Even worse, they could end up in the ranks of unemployment.

The sample taken from the RSR shows that CONACyT scholarships to study abroad are not an effective policy to produce legal researchers. Moreover, the financial stimuli disbursed through SNI and other CONACyT policies do not contribute to that goal either. The current policy regarding CONACyT training of high-level human resources is nothing more than a migratory exacerbation of the magister dixit method. The idea behind this is to send law students to the best schools around the globe and have them educated in foreign jurisdictions of applicable law, instead of generating it through national research frameworks. While it is beneficial to have lawyers trained in international law in a globalized society, national and local levels might not benefit as much from this area of expertise. The repatriation of these professionals has only one possible destiny: Mexico City. Other cities lack the necessary institutions that produce specialized legal knowledge, being these official (like ministries and judicial)171 or academic entities. The absence of legal knowledge production in these locations restrains lawyers to a very limited number of legal issues.

The author proposes this list of actions that could cultivate new generations of legal researchers in Mexico and aid the existing ones:

1. Give workshops and courses directed at existing law professors, teaching them about other teaching methods other than the magister dixit one.

2. Homologate SNI Candidate stimuli to those at Level I.

3. Standardize hiring processes to include research portfolios as a requirement/consideration to employ a law professor (at least in public HEIs).

4. If point 3 is implemented, research stimuli should be added to the law professors’ main salary. This could trigger the debate to effectively cancel the SNI.

5. Channel MLGS with intentions of joining academia towards platforms where they can conduct research until research professor positions become available. Law schools could advocate for spaces reserved for legal researchers on platforms like CONACyT professorships.

These changes, although available to all MLGS and law professors in the country, should be directed to be applied in HEIs outside Mexico City. Law schools outside the capital city and the three other student cities (Guadalajara, Monterrey and Puebla) have given up on the production of legal knowledge and, even further, opinion to a limited number of legal research centers. Legal research outside these cities, with a few exceptions (Tabasco, for example, has the largest number of legal researchers and PNPC programs in all southeastern Mexico), seems to be a pretty effort that embellishes a lawyer’s curriculum vitae. Just looking at Mexico City, legal research sets a line of defense against dubious legislation that tarnishes the Rule of Law to favor certain interests.

One of the MLGS interviewed for this article shared that: “Legal researchers and the institutions where they worked are an excellent technical counterweight to any legal controversy that may arise from Mexico’s legislative bodies”.

That is the importance of legal researchers and that is why the brain drain in the legal sphere must be addressed soon. Migration should be a personal decision, not a professional shot in the dark.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)